Structural and institutional aspects surrounding Japanese self-initiated expatriates’ career opportunities in East and Southeast Asian societies

Автор: Ishida Kenji, Arita Shin, Genji Keiko, Kagawa Mei

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Foreign experience

Статья в выпуске: 5 (65) т.12, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This paper investigates how Japanese SIE’s labor markets in Asian societies provide career opportunities for young Japanese workers. The number of locally employed Japanese workers in Asia has increased since the 1990s. Previous studies, which have relied on the Lifestyle Migration view, pointed that the primary reason for expatriation is self-seeking and that Japanese expatriates feel finding something worthwhile for their lives by expatriation at the expense of status attainment. However, these studies paid little attention to the demand-side aspects of Japanese SIE’s career, which directly determines their opportunities. This study aims to provide some empirical findings based on the structural and institutional accounts that are different from the previous studies. The authors analyze the interview data of staffing agencies and the salary data in Singapore, Hong Kong, Thailand, Indonesia, and China, which the Japanese expatriate workers are likely to choose as destinations. From the qualitative analyses of the interview data, the authors find four dimensions relating to Japanese expatriate’s labor market chances; market growth in the local society, the existence of Japanese community, legal restriction of issuing work permits, and the degree of localization of Japanese firms. According to these factors, it is possible to classify the five societies into two groups: one has a premium of Japanese self-initiated expatriate workers, and the other does not. The quantitative analyses using the salary data from a staffing agency also confirm the cross-society difference of economic remuneration. In China, Indonesia, and Thailand which are included in the former group, the salary of native Japanese workers is significantly higher than those of other worker types, but it is not in Singapore and Hong Kong. The authors discuss the differences between the present study and previous literature and the future research prospects in the concluding remarks.

Self-initiated expatriate worker, local employment, career opportunity structure, staffing agencies, local japanese firm, asia

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147224213

IDR: 147224213 | УДК: 314.745 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2019.5.65.12

Текст научной статьи Structural and institutional aspects surrounding Japanese self-initiated expatriates’ career opportunities in East and Southeast Asian societies

Population Dynamics of Japanese Out-Migrants in Asia

Is Japan an inward-looking society? The word ‘inward-looking society’ means the majority of people in society look to only interests within their home country and do not open their eyes on international or transnational environments. The inward-looking society image in Japan is often debatable [1]. An international comparative survey by CAO (Cabinet Office of Japan) reports that Japanese youth are not much interested in living abroad1. The percentage of Japanese youth from 13 to 29, who want to settle in other countries, is just about 20% in the CAO’s survey.

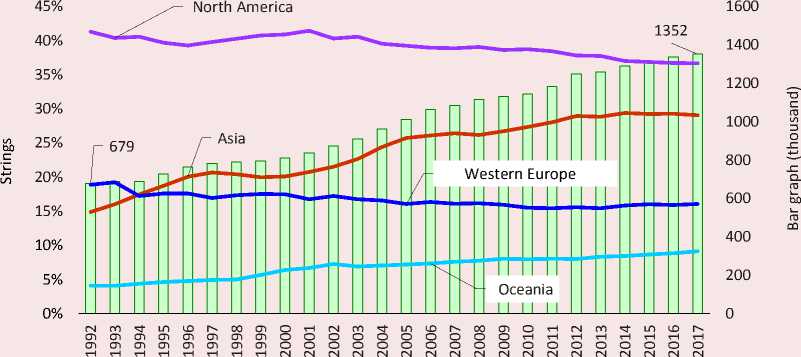

Although Japanese young people seem to be reluctant to live and work abroard, the number of Japanese out-migrants has increased since the early 1990s. Figure 1 illustrates the trend of Japanese out-migrant population size across the world and proportions in popular regions where they move. The bar chart in Figure 1 means the total size of Japanese out-migrants, and it grows up almost monotonically and gets almost twice between 1992 and 2017. In contrast with the Western societies, Asia has gathered more and more Japanese out-migrants for 25 years since the early 1990s, and the increase of the total out-migrant population principally comes from Asia.

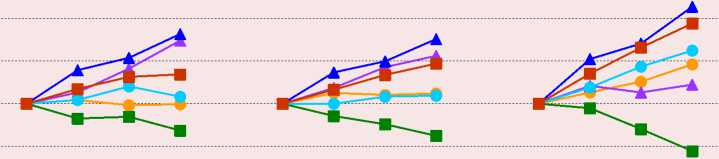

In addition to the overall trend, this official statistics result gives a totally different impression from the one the ‘inward-looking’ Japanese youth discourse might imply. To describe population changes within the same age groups, Figure 2 shows the relative sizes of Japanese out-migrants in each year compared

Figure 1. Overall number of Japanese out-migrants across the world

Source: Authors’ calculation of the Annual Report of Statistics on Japanese Nationals Overseas by Ministry of Foreign Affairs

1,3

Figure 2. The relative growth of Japanese out-migrants by regions and age groups

1,2

1,1

Е

2014 2015 2016 2017

Asia

2014 2015 2016 2017

North America

2014 2015 2016 2017

Europe

0,9

0,8

■ 30

— ■ — 60 and more

to the result in 2014. We calculated them by major three destination regions and age groups2. In all three regions, the sizes of Japanese out-migrants in their 20s and 40s commonly grow as well as older age groups such as people in their 50s and more3 [2]. The proportion of Japanese people in their 30s slight decreases, but the absolute number of them is still much more than younger age groups4. In Asia, which this paper will solely focus on, most Japanese out-migrants are not international students or working holiday makers but employees of private companies. These statistical figures imply that the transnational career experience is progressively emerging.

There are two types of Japanese out-migrants; one is corporate expatriate (CE), and the other is so-called self-initiated expatriate (SIE) [3]. The corporate expatriates are those who are assigned to local branches by their headquarters, and they usually take managerial positions of the local organizations. Unlike the CEs, the SIEs find their positions by themselves and move to the destinations. CE follows the personnel policies and practices by the headquarter in most cases, and its cross-border mobility is located within the organizational career ladder. However, SIE does not have direct employment relationships with the headquarters.

Figures 1 and 2 include both CE and SIE. Unfortunately, there is not an exact figure of SIEs due to a lack of well-designed survey with a focus on them. However, it is possible to approximately see the number of SIEs by that of female employees in private companies. It is because male expatriates dominantly consist of CEs, and a research report of CE figures out that 98.2% of CEs are male workers [4]. The informants of staffing agencies in this study also frequently point that the male-female ratio of SIEs is 50/50 or 60/40. Given that information, the number of male SIE workers in private firms must be close to that of female SIE workers.

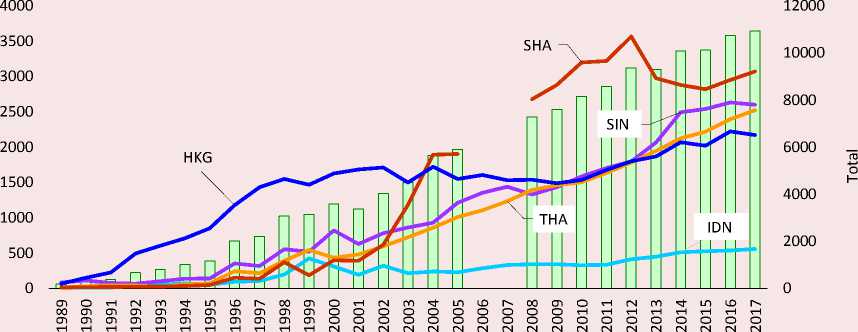

Figure 3 depicts the number of female workers employed by private firms in each region. We select five regions that are popular among Japanese SIEs5, and the bar chart in Figure 3 is the total amount of them. The total number has increased since the 1990s, and it approaches over ten thousand in 2017, that is

Figure 3. The number of female employees in private companies in major Asian destinations

Total (5 regions) Indonesia ^^^^^^^е Singapore

^^^^^^^*Thailand Shanghai ^^^^^^е Hong Kong

Source: Authors’ calculation of the Annual Report of Statistics on Japanese Nationals Overseas by Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

30 times larger than that in 1990. Hong Kong used to be the most popular destination among Japanese SIEs before the early 2000s, but its relative presence has got smaller nowadays. Instead, Shanghai, Singapore, and Thailand have gathered female SIEs, and the number of them in Indonesia also increases. From these results, there is possibly a similar number of male Japanese SIEs in these societies today.

Research Question and Agenda of the Present Study

The research question in the present study is how the Japanese SIE’s labor markets in Asian societies provide career opportunities for young Japanese workers. Previous studies are likely to stress cultural aspects of the Japanese expatriation. A majority of them has focused on how Japanese SIEs interpret their career experiences in their daily lives, because they do not always want to work overseas for higher sosicoeconomic statuses. Working overseas is a means of seeking one’s better way of life, and this kind of expatriation is called the Lifestyle Migration [5][6].

This paper, instead, focuses on the labor market structural factors, like the labor demand-supply relationship in destination societies, directly determines the SIE’s opportunity. The previous studies have had relatively few attentions to the demand-side aspects of Japanese SIE’s career. This paper investigates their opportunities from the labor demand-side’s viewpoint through intensive field interviews for staffing agencies in Asian countries and other statistical information.

The present study illuminates the opportunity structure of Japanese SIE which will vary across Asian societies according to some conditions. With interview data and salary information publicly available, this paper will delineate four dimensions; market growth in the local society, existence of Japanese community, legal restriction of issuing work permits, and the degree of localization of Japanese firms. Combinations of these factors provide different career opportunity structures to Japanese SIE workers in each society. Detailed analyses will follow the literature review and description of data this paper utilizes.

Список литературы Structural and institutional aspects surrounding Japanese self-initiated expatriates’ career opportunities in East and Southeast Asian societies

- Burgess C. To Globalise or Not to Globalise? ‘Inward-Looking Youth' as Scapegoats for Japan's Failure to Secure and Cultivate ‘Global Human Resources.' Globalisation, Societies and Education, 2015, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 487-507.

- Toyota M. Xiang B. The Emerging Transitional ‘Retirement Industry' in Southeast Asia. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 2012, vol. 32, no. 11, pp. 708-719.

- Habti D., Elo M. (Eds.). Global Mobility of Highly Skilled People: Multidisciplinary Perspective on Self-initiated Expatriation. New York: Springer, 2018. 304 p.

- JILPT. 2008. dai nana kai kaigai haken kinmusya no syokugyo to seikatsu ni kansuru chosa kekka [The Research Report of the 7th Wave of the Survey on the Work and Life of Corporate Expatriates]. Tokyo: JILPT, 2008. 290 p. (in Japanese).

- Benson M. O'Reilly K. Migration and the Search for a Better Way of Life: A Critical Exploration of Lifestyle Migration. Sociological Review, 2009, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 608-625.

- Benson M., O'Reilly K. (Eds.). Lifestyle Migration: Expectations, Aspirations and Experiences, London: Routledge, 2009. 178 p.

- Borjas G.J. Economic theory and international migration. International Migration Review, 1989, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 457-485.

- Borjas G.J. The intergenerational mobility of Immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics, 1993, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 113-135.

- Limpangong C. Migration as a strategy for maintaining a middle-class identity: the case of professional Filipino women in Melbourne. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 2013, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 307-329.

- Xu H., Wu Y. Lifestyle mobility in China: context, perspective and prospects. Mobilities, 2016, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 509-520.

- HOF H. ‘Worklife Pathways' to Singapore and Japan: gender and racial dynamics in Europeans' mobility to Asia. Social Science Japan Journal, 2018, vol. 21, no.1, pp. 45-65.

- Beamish P.W., Inkpen A.C. Japanese firms and the decline of the Japanese expatriate. Journal of World Business, 1998, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 35-50.

- Genda Y. Who really lost jobs in Japan? Youth employment in an aging Japanese society. In: Ogura S., Tachibanaki T., Wise D.A. (Eds.). Labor Markets and Firm Benefit Policies in Japan and the Unitedstates. 2003, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Pp. 103-133.

- Thang L-L., Maclachlan E., Goda M. Living in ‘My Space': Japanese working women in Singapore. Geographical Sciences, 2006, vol. 61, no. 3, pp. 156-171.

- Kamiya H. Niwa T. (Eds.). Wakamono tachi no kaigai syussyoku: ‘gurobaru' jinzai no genzai [Working Overseas by Japanese Youth: Current Global Human Resources]. Tokyo: Nakanishiya Syuppan, 2018. 205 p. [in Japanese]

- Hamaaki J., Hori M., Maeda S., Murata K. Changes in the Japanese employment system in the two lost decades. ILR Review, 2012, vol. 65, no. 4, pp. 810-846.

- Kato E., Kukimoto S. Gurobaru jinzai towa nanika [Who are Global Human Resources?]. Tokyo: Seikyusha Publishing, 2016. 318 p. [in Japanese].

- Nagatomo J. Nihon shakai wo ‘nogareru' [Escape from Japanese Society]. Tokyo: Sairyusha Publishing, 2013. 265 p. [in Japanese].

- Kawashima K. Service outsourcing and labour mobility in a digital age: transnational linkages between Japan and Dalian, China. Global Networks, 2017, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 483-499.

- Fujioka N. Jakunen erito sou to koyo roudou shisutemu no kokusaika [Non-elite Youth and Internationalization of Employment and Labor Systems]. Tokyo: Fukumura Publishing, 2017, 496 p. [in Japanese].

- Matsutani M. Introduction to the migration of locally employed workers: a sociological study on a variation of new migration under globalization, Kyoto Journal of Sociology, 2014, vol. 22, pp. 49-68. [in Japanese].

- Nakazawa T. The Japanese self-initiated migrants and international migration of the global middle-class. The Bulletin of Arts and Sciences, Meiji University, 2016, vol. 512, pp. 67-95. [in Japanese]

- DiMaggio P.J., Powel W.W. The Iron Cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 1983, vol. 48, pp. 147-160.

- Burt R.S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992. 312 p.

- Kim H. Ethnic enclave economy in urban China: the Korean immigrants in Yanbian. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 2003, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 802-828.

- Nakazawa T., Yui Y., Kamiya H. Expansion of labor market for locally hired Japanese women and its factors: a case of Singapore in the mid-2000s. Geographical Sciences, 2012, vol. 67, no. 4, pp. 153-172. [in Japanese].