Structure of the mass strata of the Russian population by level of subjective well-being

Автор: Sushko P.E.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social and economic development

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.18, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article analyses the peculiarities of differentiation of Russians by the level of their subjective well-being. Based on the data of all-Russian representative surveys obtained by the Institute of Sociology of the FCTAS RAS, the subjective well-being index is calculated and a model is proposed, including five groups that differ significantly from each other in terms of the feeling of well-being of the situation in key aspects of life – from basic needs and microcosm to assessments of the parameters of the place of residence and the relationship between the individual and the state. The first group unites Russians with predominantly negative assessments of the situation in most of the proposed areas of life, but its number is small and such assessments are not typical for Russian society (4.3%). The second group includes 46.7% of Russians with satisfactory assessments in most spheres of life, but in which the share of negative assessments dominates over positive ones. This large group forms a zone of unstable subjective well-being. The next three groups unite Russians with satisfactory and/or positive assessments of the situation in different spheres of life. At the same time, these three groups also differ significantly among themselves. In terms of socio-demographic characteristics of the individual, the income level, professional affiliation and age of the respondent have the greatest differentiating power in the context of assessments of subjective well-being. However, the correlation of the level of subjective well-being with income and occupation has increased over the last two decades, while with age it has significantly decreased. From the point of view of differences in lifestyle, the key factors that can increase or decrease the level of own well-being are both a set of property characteristics and a list of achieved life goals, as well as the specifics of experienced problems, perception of the dynamics of the situation in society as a whole and the ability to plan one's own life

Social well-being, subjective well-being, well-being index, social stratification, quality of life, social inequality, social policy, Russian society

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147251834

IDR: 147251834 | УДК: 316.344, LBC 60.524 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2025.4.100.8

Текст научной статьи Structure of the mass strata of the Russian population by level of subjective well-being

The agenda concerning social well-being is one of the key and at the same time quite controversial in the social sciences (Leontiev, 2020; Sociological Approaches ..., 2021; Anikin et al., 2024). The growing interest of researchers in this topic in recent years is due both to the desire of scientists, against the background of socio-economic and political transformations taking place in the country and the world, to assess the depth and scale of social changes, and to an attempt to concretize public demands, which are often based not only on objective criteria, but also on a fairly wide range of subjective assessments and feelings, the fullness of which can hardly be reflected in a single study (Kuchenkova, 2016). At the same time, the researchers’ increased attention toward the subjective measurement of well-being and the search for relevant indicators of its assessment was largely caused by noticeable discrepancies between the declared statistical data and people’s selfassessments of their situation and life in general (Stiglitz et al., 2016).

It was not always the case that any objective improvements in the life of society were positively assessed by the population at the individual level and vice versa. This was due to the fact that official statistics and, for example, generalized indicators of GDP, GNP or average income indicators of the population did not fully reflect the real internal differentiation of the population, contradicting the general growth of social inequalities caused, among other things, by the intensified processes of globalization and informatization. Against this background, scientists have attempted to develop a universal set of objective characteristics that could comprehensively characterize the actual situation regarding the well-being of the population; however, researchers have encountered a number of methodological problems that make it impossible, due to the different significance of the indicators, to properly record both the specifics of intergroup differences, including on social and cultural grounds, and the role of individual characteristics related to socio-demographic parameters, life cycle stages, etc. (Kuchenkova, 2020).

Researchers, primarily economists, drew attention to such discrepancies between growing economic indicators, which should have indicated a corresponding increase in the well-being and overall quality of life, and individuals’ selfassessments of their actual level of social wellbeing, which did not always show the same positive dynamics, back in the mid-1970s. By this time, a sufficient amount of empirical data had accumulated, proving that the increase in the level of material well-being of nations affects the increase in life satisfaction and happiness less than expected, and sometimes does not have any effect at all (Argyle, 2003). Therefore, the level of material achievements of a person and a nation cannot be considered as the only indicator of the quality of life. According to A. Peccei, although the policy of abundance is able to solve some problems and alleviate others, the sources of human dissatisfaction do not cease to exist even against this background (Peccei, 1985, p. 151).

The discrepancies between material well-being and its perception indicate the limitations of using only an economic approach in analyzing such a complex and multidimensional phenomenon as social well-being. The academic community is well aware of this and it served as an impetus for the development of a subjective direction in the social sciences, including in psychological and sociological studies of social well-being. But while in psychology the main focus is on the problem of people’s perception of their position in various spheres of life under the influence of emotional factors and the general psychological state of the individual, in sociology well-being is analyzed primarily at the level of society as an integral system at a certain stage of its development, and in the context of the current social situation. The stage of development and the social situation largely determine the subjective perception of social reality at the individual level, in some cases coming into conflict with the expectations and ideals of each individual (Salnikova, 2017).

In general, the trend toward studying subjective indicators of well-being originates from the works of R. Easterlin, which later sparked a serious scientific debate by revealing a discrepancy between subjective assessments of social well-being and its objective indicators, primarily in terms of financial status (Easterlin, 1976). This was followed by numerous publications both in Russia (Mareeva, 2018; Shirokanova, 2020; Sushko, 2023) and abroad (Fleche et al., 2011; Binder, 2014; Kwarcinski et al., 2024), in which the concept of subjective wellbeing and its possible empirically fixed indicators were studied from different theoretical and methodological approaches. Many works were based on a one-dimensional approach involving the study of individual components of subjective well-being and the factors influencing it, most often in the context of various social groups (Kislitsina, 2016). However, attempts have also been made at comprehensive operationalization, suggesting that subjective well-being cannot be reduced to just one specific indicator (and even the sum of the estimates of indicators), but represents a certain sense of “inner satisfaction” with certain aspects of one’s own life, which largely determine not only the model of consumption of vital goods, but ultimately affecting the social position and life of the individual as a whole (Sushko, 2024).

At the same time, in foreign studies, subjective well-being is traditionally considered as a multidimensional construct, which, as a rule, includes cognitive assessments (overall satisfaction with life and its individual spheres), as well as affective components reflecting emotional balance and happiness (Ryff, 1989; Diener et al., 1999). Some works emphasize the importance of both objective living conditions and their individual perception (Cummins, 2000; Veenhoven, 2008). At the same time, approaches focusing on the assessment of various spheres of life are widely used within the framework of the concept of quality of life, where an individual’s well-being is determined through satisfaction with key areas of life (Nussbaum, 2011).

In this regard, subjective well-being is understood as a kind of comprehensive assessment reflecting people’s satisfaction with the activities of various social institutions, including taking into account the current economic and socio-political situation in the country (Shirokanova, 2020), that is, the social context that mediates individuals’ perception of various aspects of their own lives. This has prompted a number of large research centers to monitor changes in Russians’ assessments of individual components of subjective well-being under the influence of specific social events and to use various sociological tools to measure wellbeing, which is called “in the moment”1. This is the basis for various cross-country studies of the subjective component of social well-being, which are also aimed at analyzing and comparing its status, material, cultural and other characteristics (for example, separate thematic blocks in the ISSP, LiTS, EVS, ESS and other international projects are devoted to this issue).

We should note that according to many international indices measuring happiness, wellbeing and life satisfaction, Russia is not among the leaders, although it is not an absolute outsider. For example, according to the recent World Happiness Report, Russia’s score was 5.79 out of 10, which gave it 67th place (in the middle of the ranking) out of 147 countries. While in previous years Russia’s place has fluctuated significantly (from 49 in 2017 to 68 in 2019)2, which underlines the dynamic nature of subjective well-being (at least its affective aspect) in the country. If we talk about cognitive and subjective well-being, then Russia’s place on the global background is still somewhat shifted downward. According to the OECD Better Life Index study, the level of life satisfaction in Russia (5.5 points out of 10) is noticeably lower than the average in comparison with other countries3. Thus, Russia is a society with a moderate level of subjective well-being, but its fluctuations may indicate significant internal differentiation, which especially highlights the need for an in-depth study of its internal structure.

In addition, against the background of the still relatively high level of social inequality in Russian society (the Gini coefficient in Russia in 2024 was 0.4084) and the growing demands of the population for its leveling (Mareeva, 2024), the issue of subjective well-being remains relevant. At the same time, for Russians, taking into account the very limited resource of social networks, which is especially strongly differentiating the country’s population (Society of Unequal ..., 2022), the request to smooth out inequalities turns out to be closely linked to the concept of social justice, which is interpreted not only and not so much in the context of equalizing the material standard of living, but rather in achieving equality of opportunities in the implementation of own life aspirations (Kolennikova, 2024a). In this regard, the issue of Russians’ self-assessments of their well-being in key areas of life, and not just in terms of financial status or overall life satisfaction, becomes a cornerstone. The answer to it reflects the level of social stability and, in general, speaks about the legitimacy of the entire socio-economic and socio-political system, as well as reveals key public demands that manifest themselves precisely from the standpoint of social well-being and are not always reflected only in terms of socio-demographic or socio-economic criteria.

The aim of our work is to attempt to compre hensively analyze such self-assessments and build a model of subjective well-being that differentiates the Russian population from the pole of subjective disadvantage to a complete sense of well-being in key areas of life. In our opinion, this will make it possible to clarify the understanding of the term “subjective well-being” and consider it not as a minor aspect, but as a phenomenon – a complex phenomenon related or conditioned by various factors. At the same time, the results of the study make it possible to expand the list of possible needs and problems of various groups of the Russian population, which can contribute to improving the effectiveness of measures aimed at improving the quality of life and social well-being of citizens, taking into account the real feelings and priorities of various segments of society.

The empirical basis for the analysis included data obtained in different years by the Institute of Sociology FCTAS RAS5. The model of subjective well-being was based on respondents’ answers to the question “How do you assess the following aspects of your life?”, which included 16 closures with the following meaningful answers: “good”, “satisfactory” and “bad”6. Taking into account the theoretical framework outlined above and the specifics of the empirical data analyzed, subjective well-being is conceptualized primarily as an individual’s cognitive assessment of various aspects of their life and general satisfaction with it, but does not affect their affective components of subjective well-being and other integrative experiences, which is beyond the scope of the subject of the article.

Zones of subjective well-being: What did the empirical data show?

As noted above, for a comprehensive analysis of subjective well-being, a special Subjective WellBeing Index (hereinafter referred to as SWB Index) was constructed based on assessments of 16 spheres of life that relate to both the basic needs of a person and their microcosm, as well as to the parameters of an individual’s place of residence in the broadest sense of the word, and its interrelationships with the state7. At the same time, the choice of certain spheres of life for assessing subjective well-being is not arbitrary.

First, it is based on a synthesis of well-established theoretical concepts of quality of life and well-being, which identify key areas of an individual’s life that affect the overall sense of satisfaction. These areas cover both basic material and living conditions (income, housing, food) and more complex social aspects (health, work, family, friends, security, education, leisure, place of residence, relations with the state, etc.), which allows obtaining a comprehensive picture of the cognitive component of subjective well-being.

Second, the choice of these areas is due to the long-term experience of monitoring studies at the Institute of Sociology FCTAS RAS, during which the importance of the influence of these aspects of life on Russians’ sense of well-being was empirically confirmed. The 16 indicators presented in the article make it possible not only to assess the current situation, but also to trace the dynamics of changes in various spheres of life, which is especially important for understanding the transformational processes taking place in Russian society.

So, for the respondent’s choice of one of the proposed answers for each of the variables included in the SWB Index, an appropriate score was assigned (1 point – “good”, 0.5 points – “satisfactory”, 0 points – “bad”). At the same time, the legality of combining various indicators into a single index and assigning them equal weights is justified by the high Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (0.905), which indicates significant internal consistency of all elements of the SWB Index. This confirms that the selected 16 spheres of life (despite the existing differences in their semantic content) are perceived by the respondents as interrelated components of a common sense of well-being and therefore can be combined into a single measuring instrument.

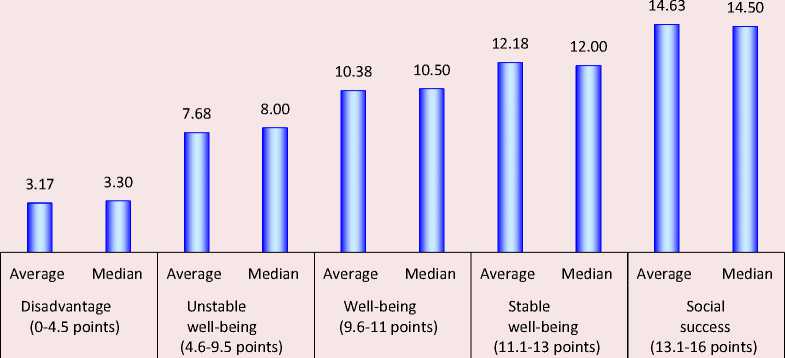

The SWB Index was calculated in relation to three sets of data collected based on the results of monitoring studies by the Institute of Sociology (IS) FCTAS RAS. The values of the SWB Index ranged from 0 to 16 points, and the average and median values did not differ significantly in all years (Tab. 1). This is an indirect evidence of the quality of the available data and the lack of asymmetry (mass statistical outliers) in them, as well as the relatively high homogeneity of the obtained estimates of subjective well-being. However, it is possible to assess the degree of this homogeneity only after resolving the issue of the values of the conditional boundaries of groups that differ in their sense of well-being in a number of designated aspects.

When defining these boundaries, we focused on minimizing differences in scores within groups and maximizing them between enlarged groups. Based on the results of this analysis, five groups were identified ranging from subjective disadvantage to social success (Fig. 1). The average and median values of the SWB Index within the groups were also very close, but they differed significantly between the enlarged groups, especially the polar ones. Checking the significance of statistical differences confirmed them8.

Table 1. Dynamics of average and median values of the SWB Index, 2003–2024, points

|

Survey year |

Average value |

Median value |

|

2024 |

9.8 |

9.5 |

|

2014 |

9.8 |

9.5 |

|

2003 |

7.9 |

7.5 |

|

Source: own calculations based on IS FCTAS RAS data. |

||

Figure 1. Average and median values of the SWB Index in groups with different levels of subjective well-being, 2024, %

Source: own calculations based on IS FCTAS RAS data.

Based on the above criteria for the validity of the constructed SWB Index, we proceed to a meaningful interpretation of the most typical assessments of the subjective well-being of representatives of each of the selected groups9 ( Tab. 2 ).

Thus, the first group brought together Russians who more often consider their position a disadvantaged one according to various criteria. Thus, the main composition of this group described the situation in most of the considered spheres of life as bad. And even in those areas where bad assessments did not dominate, they significantly exceeded the similar shares in the other four groups and the average across the array. In this sense, the subjective disadvantage for Russians is associated with an absolutely outsider position, which, however, is the exception rather than the rule for Russian society (4.3%).

The second group unites Russians, who already have satisfactory ratings in all areas, but the proportion of those who assess the situation as bad in most areas exceeds the number of those who see it as good, including when assessing the basic components – material security, food and clothing. That is, even with regard to the availability of the minimum necessary material base, this group cannot be called stable, despite the dominant feeling of satisfaction with various aspects of life. Numerically, this is the largest group, and its subjective position largely correlates with studies of income stratification, which characterize Russian society as not a society of poverty, but a society of mass low-income (The model of income ..., 2018).

The third group includes 15.4% of Russians with dominant satisfactory assessments of the situation in most areas of life; but in this group the proportion of good assessments already exceeded the proportion of bad in various areas, and in three of the areas related to housing, as well as important components of social capital (family relationships and opportunities to communicate with friends) good assessments dominated.

In the fourth group (14.2%) of Russians, good assessments dominated in 11 of the 16 areas of life under consideration, while bad grades in most aspects did not exceed the statistical margin of error of 3–5%. Nevertheless, the situation in areas related to material security, health status, vacation opportunities and obtaining the necessary education and knowledge, as well as the position in society and the level of personal security, was assessed by representatives of this group more as “satisfactory” than “good”. In this sense, the fifth group, which unites 19.5% of Russians, is characterized by the dominance of good grades in all considered areas of life and acts as a polar in relation to the group forming the pole of subjective disadvantage. Thus, in Russian society, subjective well-being is a stable norm, and disadvantage is a rather rare phenomenon. However, subjective well-being, as can be seen from the data presented, is highly differentiated, and Russian society is heterogeneous in this sense. This thesis corresponds to the data of Russian studies that the differentiation in terms of positive privilege (or in our case, subjective well-being) in Russian society is much deeper than in terms of negative privilege (or subjective disadvantage) (Society of Unequal ..., 2022).

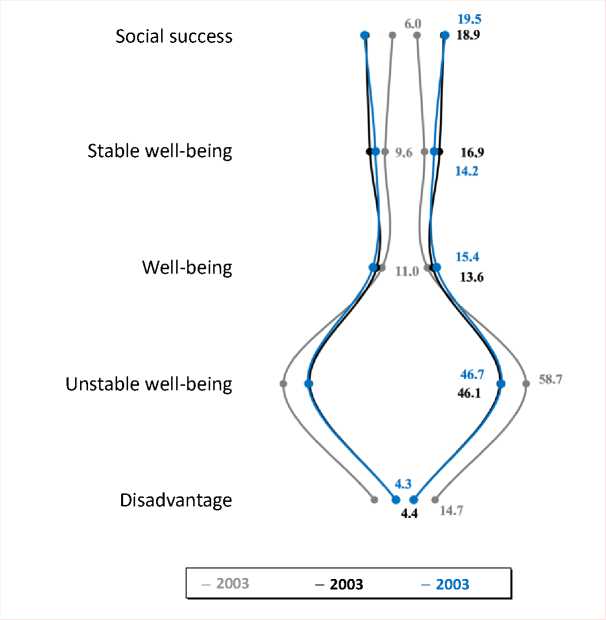

This partly reflects the dynamics of the number of groups with different levels of subjective wellbeing, indicating that after 2003 there was a noticeable transformation in the minds of Russians in terms of their own well-being for the better ( Fig. 2 ). However, since then, the dynamics of the assessments under consideration have remained stable, and the zone of relatively stable subjective wellbeing in relation to the group of unstable subjective well-being and the adjacent group of subjective disadvantage have been numerically leveled. The visual model of subjective well-being shows that the zone of stable well-being is more heterogeneous than a group whose subjective well-being is rather unstable.

Table 2. Assessments of various aspects of life by Russians from different groups with different levels of subjective well-being*, 2024, %

|

Assessments of various aspects of life |

Disadvantage |

Unstable well-being |

Well-being |

Stable well-being |

Social success |

|

|

Financial security |

Good |

- |

2.7 |

13.4 |

31.9 |

76.7 |

|

Satisfactory |

6.0 |

71.3 |

83.1 |

66.3 |

23.3 |

|

|

Bad |

94.0 |

26.0 |

3.6 |

1.8 |

- |

|

|

Nutrition |

Good |

- |

11.0 |

45.0 |

71.9 |

95.9 |

|

Satisfactory |

40.5 |

83.7 |

55.0 |

28.1 |

4.1 |

|

|

Bad |

59.5 |

5.3 |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Clothing |

Good |

- |

6.8 |

33.9 |

62.3 |

92.3 |

|

Satisfactory |

34.5 |

85.8 |

66.1 |

37.7 |

7.7 |

|

|

Bad |

65.5 |

7.4 |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Health status |

Good |

2.4 |

9.2 |

27.0 |

46.3 |

80.0 |

|

Satisfactory |

32.1 |

73.8 |

70.0 |

51.2 |

19.5 |

|

|

Bad |

65.5 |

16.9 |

2.9 |

2.5 |

0.5 |

|

|

Housing conditions |

Good |

2.4 |

19.0 |

52.3 |

65.6 |

90.5 |

|

Satisfactory |

53.6 |

72.6 |

44.1 |

30.9 |

9.2 |

|

|

Bad |

44.0 |

8.4 |

3.6 |

3.5 |

0.3 |

|

|

Family relationships |

Good |

8.6 |

38.5 |

70.3 |

84.9 |

95.4 |

|

Satisfactory |

59.3 |

56.7 |

28.4 |

14.7 |

4.6 |

|

|

Bad |

32.1 |

4.8 |

1.3 |

0.4 |

- |

|

|

Leisure activities |

Good |

- |

8.9 |

36.3 |

56.8 |

84.4 |

|

Satisfactory |

23.8 |

69.7 |

60.5 |

41.1 |

15.4 |

|

|

Bad |

76.2 |

21.4 |

3.3 |

2.1 |

0.3 |

|

|

Situation at work |

Good |

- |

8.8 |

32.9 |

57.1 |

80.4 |

|

Satisfactory |

40.0 |

78.5 |

65.3 |

40.8 |

19.6 |

|

|

Bad |

60.0 |

12.7 |

1.8 |

2.1 |

- |

|

|

Opportunity to relax during the vacation period |

Good |

- |

4.1 |

18.9 |

36.4 |

75.5 |

|

Satisfactory |

8.3 |

60.0 |

72.6 |

56.4 |

24.2 |

|

|

Bad |

91.7 |

35.8 |

8.4 |

7.1 |

0.3 |

|

|

Opportunity to communicate with friends |

Good |

4.8 |

28.2 |

66.8 |

76.1 |

93.3 |

|

Satisfactory |

61.4 |

66.0 |

31.9 |

22.9 |

6.7 |

|

|

Bad |

33.7 |

5.8 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

- |

|

|

Opportunity to realize your potential in the profession |

Good |

1.4 |

8.8 |

32.3 |

62.2 |

89.1 |

|

Satisfactory |

15.9 |

72 |

57.8 |

35.6 |

10.7 |

|

|

Bad |

82.6 |

19.2 |

9.9 |

2.2 |

0.3 |

|

|

Opportunity to receive the necessary education and knowledge |

Good |

1.4 |

7.4 |

23.2 |

44.1 |

75.1 |

|

Satisfactory |

29.2 |

71.9 |

71.7 |

52.3 |

24.4 |

|

|

Bad |

69.4 |

20.6 |

5.1 |

3.6 |

0.5 |

|

|

Place where you live (city, town, village) |

Good |

4.8 |

23.3 |

44.0 |

64.2 |

85.4 |

|

Satisfactory |

57.1 |

69.0 |

51.8 |

35.1 |

14.6 |

|

|

Bad |

38.1 |

7.6 |

4.2 |

0.7 |

- |

|

|

Your position and status in society |

Good |

2.4 |

6.8 |

28.3 |

49.5 |

81.0 |

|

Satisfactory |

35.7 |

85.0 |

67.8 |

49.8 |

18.7 |

|

|

Bad |

61.9 |

8.2 |

3.9 |

0.7 |

0.3 |

|

|

Personal security level |

Good |

1.2 |

8.3 |

24.2 |

32.3 |

66.9 |

|

Satisfactory |

39.3 |

73.7 |

69.0 |

62.5 |

31.0 |

|

|

Bad |

59.5 |

18.0 |

6.9 |

5.3 |

2.1 |

|

|

Life in general |

Good |

- |

4.9 |

25.4 |

56.8 |

93.1 |

|

Satisfactory |

29.8 |

88.7 |

73.6 |

41.8 |

6.9 |

|

|

Bad |

70.2 |

6.3 |

1.0 |

1.4 |

- |

|

|

Total for the array |

4.3 |

46.7 |

15.4 |

14.2 |

19.5 |

|

|

*Maximum values in the column are highlighted in gray. Source: own calculations based on IS FCTAS RAS data. |

||||||

Figure 2. Dynamics of the number of groups of Russians differing in the level of subjective well-being, 2003–2024, %

Source: own calculations based on IS FCTAS RAS data.

Thus, as a hypothesis, we can note that along with the rather extensive zone of unstable subjective well-being that persists in Russian society, its stable forms cover a significant number of Russians, but they are very differentiated from each other. In this regard, it is important to clarify the questions of whether we can relate these enlarged zones to each other (or whether they are not just visually or numerically differentiated from each other, but also significantly differentiated from the point of view of socio-demographic portraits of representatives of the selected groups) and, if so, how legitimate is the thesis that the Russian is society at a bifurcation point, judging by the SWB? In this sense, it is important not only to assess the dynamics of the number of different SWB zones, but also to consider the most typical characteristics of their representatives.

Features of socio-demographic portraits of groups with different levels of subjective well-being

An analysis of the dynamics of the interrelationships of individual socio-demographic characteristics with belonging to groups with different levels of subjective well-being reveals several important trends for Russian society related to the changing role of certain aspects of life that contribute to the formation of a comprehensive sense of well-being. Thus, there is an increase in the interrelationships of subjective well-being and material security. The individual’s income level throughout the period under review has not only maintained its leading position among other objective characteristics, but has also significantly strengthened its close relationship with the SWB Index over the past decade ( Tab. 3 ).

Table 3. Dynamics of Spearman correlation coefficients between individual socio-demographic characteristics and belonging to groups with different levels of subjective well-being*, 2003–2024, %, ranked in descending order of indicators in 2024

|

Criterion |

2003 |

2014 |

2024 |

|

Average per capita income for each family member relative to the settlement median |

0.328 |

0.335 |

0.379 |

|

Professional affiliation |

0.257 |

0.261 |

0.286 |

|

Age |

0.317 |

0.280 |

0.234 |

|

Marital status |

0.209 |

0.184 |

0.150 |

|

Education |

0.193 |

0.171 |

0.122 |

|

* Coefficients that have been increasing from year to year are highlighted in light gray; coefficients that have been decreasing – in dark gray. Source: own calculations based on IS FCTAS RAS data. |

|||

This indicates that material prosperity in modern conditions is still the most important element for Russians, although not the only one, for both objective and subjective well-being, since it largely determines the life chances and opportunities that an individual can focus on when assessing their own position and possible prospects in other areas of life. At the same time, it is important to make a reservation that we are mainly talking about the cognitive component of subjective wellbeing, associated precisely with assessments of the situation in key areas of life. For example, although the size of average per capita income has a close relationship with estimates of financial status and, as we see, it even increases over time, the sense of the dynamics of material wealth relative to the past or expectations of the future from the perspective of the present is much less associated with belonging to the income group, which we showed earlier in part (Sushko, 2023).

In addition, data from Russian studies confirm that the cognitive assessment of subjective wellbeing is more closely related to the level of material well-being than, for example, its affective aspect, associated with assessments of various feelings and emotions experienced by the respondent (Skachkova et al., 2024). Consequently, subjective well-being, assessed in terms of statics and dynamics, as well as from the perspective of cognitive or affective assessments, is differently related to objective and subjective factors, as well as material and nonmaterial properties10. In this regard, it is critically important to take into account the high dynamism and plasticity of subjective assessments, considering existing relationships, including from the point of view of verifying their stability in dynamics.

The criterion of professional affiliation turned out to be no less significant from the standpoint of forming a comprehensive sense of one’s own wellbeing. In many ways, this is expected and consistent, given the above indicators of the relationship between security and income, since self-realization in the professional field is closely linked to financial stability and, consequently, confidence in the future. For these reasons, the profession plays a key role not only in determining a person’s place in the system of public relations, but also becomes one of the key factors determining an individual’s ideas about their own social well-being. The strength of the relationship between this criterion and well-being assessments remains stable throughout the period in question. Accordingly, the status of unemployed will significantly reduce the level of subjective wellbeing of an individual, and vice versa – a higher professional status and qualification level will significantly increase the corresponding assessments of one’s own well-being.

Against this background, since 2003, another trend has been recorded, associated with a noticeable decrease in the relationship between education and self-assessments of well-being. This indicates the transformation of attitudes toward education in the public consciousness as one of the key channels of social mobility in post-Soviet Russia. Moreover, as it has been repeatedly shown in research, although this channel continues to operate, it is already under completely different conditions and requirements for those who wish to improve their status in this way (Human Capital ..., 2023). As higher education, including commercial education, has become more widespread, its stratification role has decreased, and it has ceased to guarantee a successful professional trajectory and corresponding material returns, but it is certainly a necessary norm for this. The trend has already been noted in the works of Russian sociologists (Konstantinovsky, Popova, 2020), but it is again found in the context of the study of subjective well-being. Despite the relatively weak correlation between education and the SWB Index, for Russians this factor remains rather secondary even at the subjective level in assessing well-being.

Over the past decade, the role of age in the context of its relationship with assessments of subjective well-being has also significantly decreased, although it still remains quite important. Nevertheless, a decrease in the closeness of the relationship between age and SWB scores may indicate a gradual smoothing of age differences in this regard and reflect trends toward the lengthening of the life cycle, within which goals that are significant for an individual can be realized. In this regard, youth is no longer considered as a key condition for feeling well-off, and a more pragmatic approach to age is being implemented, focused on its “acceptance” with all the possibilities and limitations. First of all, this is happening against the background of the expansion of the age boundaries of youth under the complex influence of the growth in the total life expectancy in a number of countries, expanding medical capabilities to maintain health, humanizing working conditions, developing educational institutions and strengthening ideas about the continuity of the educational process in the public consciousness, etc.11 However, these trends have not yet fundamentally changed the existing nature of the relationship between age and assessments of subjective well-being, when being young significantly increases the chances of feeling well in a whole range of vital areas.

At the same time, the results of the study indicate that Russian society develops models of subjective well-being that are more independent from the social environment (including the neighbor); there is a trend toward individualization and focus primarily on one’s own achievements and success. This is evidenced, among other things, by the consistent decline in the role of an individual’s family status in assessing one’s own well-being. Despite the fact that the family traditionally tops the rating of key life values and goals of Russians, the fact of its presence or absence is not a predictor of the corresponding assessments of well-being and refers rather to secondary factors among other socio-demographic characteristics of an individual. The exception is Russians who are divorced or widowed, and they are relatively more likely to feel disadvantaged. Thus, family status has some differentiating power, but rather according to the proximity of the individual to the pole of disadvantage. Family status does not affect subjective well-being in a key way ( Tab. 4 ).

Table 4. Specifics of subjective well-being in various socio-demographic groups of Russians*, 2024, %

|

Group |

Disadvantage |

Unstable well-being |

Well-being |

Stable well-being |

Social success |

Average for the array |

|

INCOME GROUPS |

||||||

|

Under 0.75 medians |

74.4 |

39.9 |

29.1 |

19.9 |

15.0 |

32.0 |

|

From 0.76 to 1.25 medians |

16.7 |

36.7 |

38.8 |

39.9 |

29.0 |

35.2 |

|

From 1.26 to 2 medians |

6.4 |

19.3 |

29.8 |

26.6 |

36.2 |

24.6 |

|

From 2.1 medians and higher |

2.6 |

4.1 |

2.4 |

13.7 |

19.8 |

8.1 |

|

PROFESSIONAL GROUPS |

||||||

|

Entrepreneurs and the selfemployed |

– |

2.4 |

2.9 |

1.8 |

7.9 |

3.4 |

|

Managers of different levels |

– |

2.8 |

2.9 |

3.9 |

6.7 |

3.6 |

|

Specialists in positions requiring higher education certificate |

2.4 |

11.4 |

20.8 |

24.2 |

25.9 |

17.1 |

|

Employees in positions that do not require higher education certificate |

1.2 |

13.0 |

6.5 |

9.8 |

11.5 |

10.8 |

|

Trade sector or consumer services employees |

5.9 |

10.7 |

9.4 |

11.6 |

11.3 |

10.6 |

|

Grade 5 workers |

8.2 |

7.1 |

14.7 |

13.7 |

10.8 |

10 |

|

Grade 1–4 workers and workers with no grade |

12.9 |

16.5 |

14.0 |

16.8 |

12.1 |

15.2 |

|

Currently unemployed |

69.4 |

36.2 |

28.7 |

18.2 |

13.8 |

29.6 |

|

AGE GROUPS |

||||||

|

18–30 |

10.4 |

18.4 |

37.2 |

49.3 |

54.8 |

24.4 |

|

31–40 |

20.1 |

22.4 |

19.0 |

21.2 |

20.6 |

21.5 |

|

41–50 |

22.7 |

23.0 |

22.5 |

18.7 |

20.6 |

22.3 |

|

51–60 |

22.0 |

16.7 |

10.8 |

6.4 |

2.4 |

15.0 |

|

61 and older |

24.9 |

19.6 |

10.4 |

4.4 |

1.6 |

16.9 |

|

MARITAL STATUS |

||||||

|

Single / single and have never been married |

10.6 |

14.5 |

15.0 |

19.3 |

20.5 |

16.3 |

|

Married |

54.1 |

55.8 |

63.8 |

64.9 |

62.6 |

59.6 |

|

Living with a partner |

4.7 |

5.1 |

4.2 |

3.5 |

5.1 |

4.8 |

|

Divorced |

12.9 |

10.6 |

7.8 |

5.3 |

7.9 |

9.0 |

|

Widower / widow |

16.5 |

13.4 |

9.1 |

6.7 |

3.6 |

10.0 |

|

EDUCATION |

||||||

|

Without professional education |

27.1 |

16.7 |

16.3 |

16.5 |

13.6 |

16.5 |

|

Secondary vocational or incomplete secondary education |

55.3 |

54.4 |

46.6 |

47.4 |

43.1 |

50.1 |

|

Higher education (including two university degrees and an academic degree) |

17.6 |

28.8 |

37.1 |

36.1 |

43.3 |

33.5 |

|

*Proportion of those who found it difficult to answer is not represented. Indicators exceeding the average for the array by more than 3–5% statistical error are highlighted, while the maximum values for the column are given in bold. Source: own calculations based on IS FCTAS RAS data. |

||||||

Over the past two decades, the conventional portrait of a subjectively prosperous Russian in terms of his/her socio-demographic indicators has undergone some significant changes. So, if in 2003 the zone of absolute subjective disadvantage was formed mainly of elderly or retired citizens, divorced or widowed, unemployed or unskilled workers, with incomes below the settlement median and without professional education (secondary vocational or incomplete higher education significantly increased the self-esteem of respondents), then by 2024 the role of the material factor and professional status in this regard has increased significantly, while the education level and age, on the contrary, have decreased. And although currently citizens with an average per capita income of less than 0.75 median, unemployed, in pre-retirement and retirement age, and without higher education are more likely to fall into the zone of subjective disadvantage; among representatives of this zone one in ten is young, more than half have a family, and almost one in five has a higher education diploma.

The specifics of the zones of stable well-being and social success have also undergone certain transformations. Subjective well-being is more represented by Russians with incomes of two medians and above (in this regard, for Russians in 2003, it was enough to have an income of 1.25 of the settlement median to have a sense of wellbeing), by Russians who have leadership positions or the status of self-employed/entrepreneur, as well as by those with a high level of education (here it is more about the totality of available “soft” and “hard” skills in demand in the labor market rather than having a diploma) (Volgin, Gimpelson, 2022). The intermediate groups are more characterized by averaging positions and combining positive and negative assessments of various aspects of their own lives.

The results obtained make it possible not only to better understand the essence of the changes in social well-being taking place in the public consciousness, but also to draw a number of generalizing conclusions about the specifics of Russian society and its current stage of development. The fact that Russians prioritize material criteria, the importance of which have not only increased over the past twenty years, but which have also become key to their sense of well-being, indicates that for the most part Russian society is still in the era of “survival” with its typical set of values and norms (Inglehart, Welzel, 2011).

Lifestyle features of groups with different levels of subjective well-being

The nature of assessments of one’s own level of social well-being is influenced by certain property characteristics of Russians and lifestyle features. Thus, the presence of durable goods in the household is relatively less common than the sample average among citizens with a low level of subjective well-being (with the exception of a refrigerator and a washing machine, which the vast majority of Russians have – 99.2 and 93.3%, respectively). While the presence of a dishwasher, air conditioner, computer, and motor vehicle is noticeably more common among Russians with a high level of subjective well-being ( Tab. 5 ). These goods are not luxury items for the country’s population, although they have not yet become the “norm”, so their differentiating power remains quite high, which is confirmed by the data from other studies (Kolennikova, 2024b). This demonstrates that subjective well-being assessments are closely related to the specifics of an individual’s lifestyle and are in many ways markers of both the real and the desired social status.

It is not surprising that the sense of well-being is also associated with some of the life goals achieved by an individual. We should note that in the mass consciousness of Russians there are well-formed normative ideas about the criteria of social success and general well-being, which in Russian society remain quite stable over time and include, first of all, the implementation of plans for a good family

Table 5. Some property characteristics of Russians from different zones of subjective well-being*, 2024, %

At the same time, the prevalence of the implementation of certain life plans among Russians with different levels of subjective well-being varies significantly (Tab. 6). Thus, the goals associated with financial and professional well-being, the desire to visit different countries, to be one’s own master, to feel informationally free and independent are among those that have the greatest impact on the formation of one’s sense of well-being. It was with an increase in the level of subjective wellbeing that the frequency of achieving these goals increased. In addition, subjectively prosperous Russians, unlike subjectively disadvantaged and precariously prosperous, manage to achieve a much larger number of goals on average. For example, in general, over 45–50% of Russians say that they have already achieved an average of nine goals from the proposed list. In other words, such an indicator can be considered a common norm for Russian society. Meanwhile, only representatives of three subjectively well-off groups meet this norm or deviate from it for the better; and among the subjectively disadvantaged groups, the group whose subjective well-being is characterized as rather unstable was the most typical implementation of no more than four goals from the list, which are related to ensuring the basic components of the microcosm of a Russian: a roof over one’s head the inner circle (family and friends) and the inner desire to live an honest life.

The portrait of representatives of various groups with different levels of subjective well-being is complemented by data on the number of life problems that Russians had to face over the past year before the survey. Thus, Russians from the “stable well-being” and “social success” groups are relatively more likely to declare the absence of serious problems in their lives ( Tab. 7 ). And those of them who did talk about any problems, more often mentioned the lack of time for everyday activities and for conditional hobbies, closed the “top three” in this group of health problems, which, however, were among the top three most common problems in each of the groups under consideration. Meanwhile, over half of the representatives of the “well-being” (51.5%) and “unstable well-being” (65.4%) groups noted that they had encountered at least two significant problems over the past year, while 57.6% of the

Table 6. Prevalence of some realized life goals among Russians with different levels of subjective well-being*, 2024, %

|

Life goal |

Disadvantage |

Unstable well-being |

Well-being |

Stable well-being |

Social success |

Average for the array (for reference) |

Correlation with the Well-Being Index (Spearman) |

|

Make good money |

4.7 |

8.8 |

16.7 |

21.4 |

40.5 |

17.8 |

0.379 |

|

Get a prestigious job |

14.1 |

18.9 |

27.1 |

34.0 |

50.5 |

28.3 |

0.332 |

|

Have an interesting job |

23.8 |

35.5 |

54.8 |

59.6 |

66.1 |

47.5 |

0.316 |

|

Live no worse than others |

23.5 |

40.1 |

62.6 |

59.6 |

68.2 |

51.1 |

0.297 |

|

Visit different countries |

3.5 |

9.8 |

14.4 |

12.4 |

22.9 |

13.2 |

0.237 |

|

Being my own boss |

20.2 |

42.1 |

50.2 |

55.1 |

66.2 |

49.0 |

0.233 |

|

Make a career (professional, political or public) |

7.1 |

12.4 |

20.0 |

19.6 |

26.4 |

17.1 |

0.219 |

|

Have free access to information about what is happening in the country and the world |

17.6 |

35.3 |

42.3 |

47.4 |

61.3 |

42.4 |

0.216 |

|

Get a good education |

28.2 |

42.8 |

49.5 |

49.1 |

63.2 |

48.1 |

0.203 |

|

Have reliable friends |

57.6 |

68.3 |

83.9 |

78.6 |

86.4 |

75.2 |

0.200 |

|

Become rich |

1.2 |

1.7 |

2.3 |

5.3 |

8.2 |

3.6 |

0.200 |

|

Create a happy family |

42.4 |

55.5 |

69.2 |

68.4 |

70.5 |

61.8 |

0.193 |

|

Become a professional in my field |

31.0 |

42.9 |

55.3 |

49.8 |

55.6 |

47.8 |

0.182 |

|

Obtain a high position in society |

1.2 |

3.2 |

2.3 |

4.2 |

10.3 |

4.5 |

0.167 |

|

Influence what happens in society or the place where I live |

2.4 |

3.1 |

4.6 |

5.3 |

11.5 |

5.3 |

0.138 |

|

Have my own business |

2.4 |

5.0 |

4.6 |

7.4 |

12.1 |

6.6 |

0.112 |

|

Live my life honestly |

63.5 |

64.7 |

74.3 |

66.9 |

71.5 |

67.8 |

0.072 |

|

Have a lot of free time and spend it as I please |

27.1 |

27.7 |

31.5 |

26.1 |

24.9 |

27.5 |

0.061 |

|

Have access to power |

2.4 |

2.7 |

3.6 |

4.9 |

6.9 |

4.0 |

0.049 |

|

Have my own apartment/house |

65.9 |

68.9 |

71.4 |

67.8 |

71.1 |

69.4 |

0.036 |

|

Become famous |

1.2 |

1.8 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

3.9 |

1.9 |

0.013 |

* Wording of the question: “What have you been striving for in your life and in which areas have you already achieved what you want?”. The proportions of those who found it difficult to answer are not shown in the table. Indicators covering over 50% of the composition of the respective groups are highlighted in gray.

Source: own calculations based on IS FCTAS RAS data.

Table 7. Specifics of subjective well-being in groups of Russians with various types of life problems*, 2024, %

|

Type of problem |

Disadvantage |

Unstable well-being |

Well-being |

Stable well-being |

Social success |

Total |

|

Health-related problems |

54.1 |

40.1 |

32.2 |

28.8 |

17.4 |

33.5 |

|

Lack of time to do what I want to do |

7.1 |

24.3 |

26.1 |

23.9 |

21.3 |

23.2 |

|

Lack of time to do all the daily chores |

9.4 |

21.3 |

21.2 |

19.3 |

22.1 |

20.7 |

|

Poor financial situation |

57.6 |

29.8 |

13.4 |

8.4 |

4.4 |

20.5 |

|

Family problems |

27.1 |

23.0 |

16.6 |

18.9 |

11.8 |

19.5 |

|

Work-related issues |

35.3 |

20.5 |

16.9 |

14.0 |

9.5 |

17.5 |

|

Problems with the ability to receive the necessary medical care |

29.4 |

19.5 |

17.3 |

13.0 |

7.4 |

16.3 |

|

Lack of social guarantees in case of old age |

24.7 |

18.1 |

9.4 |

6.7 |

3.8 |

12.7 |

|

Problems with children |

17.6 |

13.0 |

9.8 |

8.1 |

5.6 |

10.6 |

|

Housing problems |

15.3 |

9.4 |

7.2 |

8.4 |

7.2 |

8.8 |

|

Bad habits |

17.6 |

8.0 |

5.9 |

3.9 |

2.3 |

6.4 |

|

Poor nutrition |

18.8 |

7.9 |

2.6 |

4.6 |

3.6 |

6.3 |

|

Loneliness and/or lack of communication opportunities |

14.1 |

7.6 |

4.9 |

4.2 |

2.8 |

6.1 |

|

Consequences of terrorist attacks, shelling, etc. by the Ukrainian Armed Forces |

5.9 |

6.0 |

4.9 |

6.7 |

3.8 |

5.5 |

|

Problems with clothing or footwear |

14.1 |

5.9 |

2.6 |

1.8 |

1.0 |

4.2 |

|

Insecurity from violence |

9.4 |

4.6 |

1.3 |

2.1 |

1.5 |

3.4 |

|

Problems with the opportunity to get an education |

2.4 |

1.9 |

1.0 |

3.5 |

0.0 |

1.7 |

|

I believe that I live normally and have not encountered any problems |

3.5 |

19.3 |

27.0 |

40.0 |

47.2 |

28.2 |

|

* Wording of the question: “Have you had to deal with the following problems over the past year?”. The proportions of those who found it difficult to answer are not shown in the table. The indicators that exceed the average for the array by more than 3–5% of the statistical error are highlighted in gray, and the three maximum indicators in each column are highlighted in bold. Source: own calculations based on IS FCTAS RAS data. |

||||||

Table 8. Assessments of the dynamics of the situation in different spheres of society by representatives of groups with different levels of subjective well-being*, 2024, %

lack of basic material components (income level, as well as food, clothing), lack of social guarantees and generally low level of social security.

For these reasons, for Russians with different levels of subjective well-being, the nature of the changes taking place in key areas of Russian society is significant. Thus, Russians who feel a decrease in the general standard of living, indicating a deterioration in the situation with social justice in society, feeling that the situation with earning opportunities, in healthcare, and in the economy as a whole has worsened, are significantly more likely to be represented in the group of disadvantaged and Russians characterized by unstable subjective wellbeing. On the contrary, subjectively well-off groups are characterized by more optimistic assessments of these areas ( Tab. 8 ).

One of the key factors for high assessments of the situation in various areas of one’s own life is the tendency to plan it in advance. Thus, over a third of the representatives of the socially successful group plan their life for at least 3–5 years or more (32.8%), while the number of those who plan their life among the subjectively disadvantaged and even in the group of Russians characterized by unstable subjective well-being is minor (3.6 and 10.6%, respectively), and in these groups, the majority of respondents think that that life cannot be planned even for a year ahead (77.6 and 56.7%, respectively).

Conclusion

As our research has shown, the sense of wellbeing in key areas of life for at least the last two decades has been typical for the majority of Russians and is in this regard a stable norm for Russian society. This also indicates the stability of the entire socio-economic and socio-political system, into which the majority of the Russian population subjectively “fits”, and the positions of social outsiders are characteristic of its absolute minority. Nevertheless, Russian society is differentiated by the degree of subjective well-being, and five significantly different groups are distinguished by this criterion. The dynamics of their numbers since 2003 had a trend toward the spread of forms of stable subjective well-being, but by 2014 it had slowed down. Thus, the model of Russian subjective well-being that has developed by 2024 looks ambivalent, since one of the groups (the most widespread) unites Russians with mostly satisfactory assessments of different spheres of life and a relatively large bias toward negativism, and three more groups are characterized by a more optimistic perception of the situation in different spheres of life, although they are very differentiated from each other.

The peculiarities of differentiation in terms of subjective well-being are related not only to the socio-demographic characteristics of individuals and the specifics of their lifestyle, but also to the changing role of some of these factors in the sense of their own well-being. If two decades ago a relatively high level of income and a young age significantly increased the sense of well-being in various spheres of life, then in 2024 the relationship between the level of subjective well-being and income increased, and with age it weakened, giving way to professional affiliation. Thus, subjective well-being in modern Russia is still very much dependent on the availability of material resources and sources of its origin (in this case, we are talking primarily about professional status and availability of work), which already says a lot about the stage of development of Russian society, which is still characterized to a great extent by the values of survival and in particular, economic security. At the same time, the increasing role of professional status in assessing one’s own well-being indicates a gradual movement toward a new stage of development, in which the qualifications and unique skills of an individual not only provide him/ her with appropriate material benefits, but also are the foundation for personal well-being. Taking into account the coexistence of these two trends, we can argue that Russian society is still at a late industrial stage of development with a continuing high role of income, but also gaining popularity trends toward professionalization, which, however, still affects a relatively small part of society.

This is also confirmed by the fact that Russians’ assessments of their well-being reflect a trend related to the higher education becoming more available and widespread, which has led to a weakening of the relationship between one’s own sense of well-being and an individual’s level of education and, in fact, a revision of the role of education for one’s own status and sense of one’s position in society, which in the minds of Russians depend much less on having a higher education diploma than in the early 2000s and even the middle of the 2010s.

The trend toward a gradual revision of age boundaries in modern society, mainly caused by an increase in life expectancy and the expansion of the boundaries of youth, also affects subjective wellbeing. This leads to leveling age differences in Russians’ perceptions of their own well-being. Most likely, this process will continue further. The same trend in many ways forms a different view of the family, its role for the subjective well-being of the individual. In particular, the relationship between family status and belonging to a group with a certain level of subjective well-being decreased during the observed period, although events leading to family breakdown (divorce or death of one of the spouses) have a high differentiating force based on signs of disadvantage.

The identified socio-demographic features of groups with different levels of subjective well-being are complemented by lifestyle characteristics that further demonstrate the heterogeneity of the “stable well-being” zone, which includes three groups of approximately equal size. Thus, subjective wellbeing and especially its stable forms are determined, first, through the multiplicity of realized life goals, and second, through the priority of goals related to providing high qualifications, building up relevant professional and social skills, and getting to know other countries (new experience). In the so-called heyday of artificial intelligence, almost half of the Russian population already understands and implements in practice what already determines and is likely to determine its well-being in the future, and in every sense of the word. In the other two groups (“disadvantage” and “unstable well-being”), these trends are relatively less widespread, but they are partly noticeable among their representatives. Nevertheless, the issue of barriers to the implementation of significant life goals and the formation of a corresponding sense of subjective well-being remains relevant for almost half of the Russian population. In addition, “stable well-being” determines the presence of fewer significant problems for the individual that he had to face in the last year. As the level of subjective wellbeing increases, the nature of possible problems also changes – problems with the “base” are less relevant, and lack of time, including for selfexpression, comes to the fore. With an increase in subjective well-being, its relationship with the tendency to plan life and, in general, to assess the structure of the whole society more optimistically, increases.

Taking into account the identified features of the analyzed groups, we are still inclined to answer the question about the possible bifurcation point traversed by Russian society in the negative, primarily due to the continuing close interrelationships of a sense of one’s own well-being with ensuring economic security and stability of the microcosm, as well as the rather high heterogeneity of the zone of “stable well-being”. However, this does not negate the trends in the movement of Russian society toward a qualitatively different state, which are fixed in it and affect, although not the majority, but a significant part of the Russian population. Moreover, on the one hand, the subjective well-being of this part is largely determined by the values of self-expression (profession, free time, life planning, etc.); on the other hand, Russians will have to define the boundaries of these values more clearly, taking into account current trends in age perception, the changing role of education, family and constantly developing technological innovations.