Суицидальные попытки у мужчин и женщин на фоне посттравматического стрессового расстройства: роль безнадёжности и черт личности

Автор: Розанов В.А., Вукс А.Я., Караваева Т.А., Алтынбекова Г.И.

Журнал: Суицидология @suicidology

Статья в выпуске: 3 (56) т.15, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Проблема взаимосвязи посттравматических состояний и суицидального поведения в последнее время приобретает всё большую актуальность. Несмотря на то, что чаще всего наличие посттравматического стрессового расстройства (ПТСР) повышает риск суицида, особенности нефатального суицидального поведения среди женщин и мужчин на фоне ПТСР недостаточно изучены. Цель - изучить особенности нефатального суицидального поведения мужчин и женщин с диагнозом ПТСР в сравнении с суицидентами без явных психиатрических расстройств.

Суицидальная попытка, посттравматическое стрессовое расстройство, намеренность суицидального акта, безнадёжность, черты личности, большая пятёрка, мужчины и женщины

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140307860

IDR: 140307860 | УДК: 616.89-008 | DOI: 10.32878/suiciderus.24-15-03(56)-48-73

Текст научной статьи Суицидальные попытки у мужчин и женщин на фоне посттравматического стрессового расстройства: роль безнадёжности и черт личности

Научно-практический журнал

Согласно многочисленным наблюдениям, любое According to numerous observations, психическое расстройство повышает риск суици- any mental disorder increases the risk of дальной попытки (СП), которая может закончиться смертельным исходом [1, 2]. В то же время, далеко не все, кто страдает нарушениями психического здоровья, пытаются покончить с собой. Это ставит вопрос о тех факторах, которые определяют риск суицида при психических расстройствах, а также о том, какие расстройства чаще ассоциированы с суицидами или суицидальными попытками и в какой степени они повышают риск. Наиболее часто среди диагнозов, которые встречаются у тех, кто совершил СП нефатального характера и поступил в медицинское учреждение общего профиля, упоминаются депрессия и различные зависимости, несколько реже психозы и личностные расстройства [3]. У значительной части лиц с СП также выявляются расстройства адаптации в виде острых ситуационных реакций [4]. Интересно отметить, что по данным отечественных работ в этом списке очень редко упоминается ПТСР.

Основными факторами, которые подталкивают психиатрических пациентов к суициду, являются страдания, связанные с самим расстройством, а именно социальная дезадаптация, снижение качества жизни, чувство неудовлетворённости жизнью, стигматизация и самостигматизация, часто переживаемое субъективное ощущение стресса, неспособность функционировать, проблемы со своим окружением и социальные проблемы в более широком плане [1]. В то же время, эти же нарушения психического здоровья могут быть следствием ряда особенностей темперамента, поведенческих и характерологических черт, личностных особенностей, присущих как пациентам, так и здоровым людям, которые также имеют значение как предрасполагающие факторы суицидальности [5]. Иными словами, психические расстройства повышают риск СП не только сами по себе, но и через разнообразные психопатологические нарушения, которые необходимо выявлять другими способами, используя соответствующие психометрические инструменты. Это такие черты и поведенческие характеристики, как нейротизм, импульсивность, враждебность, агрессивность, гнев, интровер-тированность, склонность к риску, нарушения саморегуляции и т.д. [6]. Эти же черты часто рассматриваются как психопатологические проявления стресс-диатеза, который имеет глубокие нейробиологиче-ские корни и который лежит в основе как ПТСР, так и ряда других расстройств и, в конечном счёте, суицидального поведения [7, 8].

Среди психических расстройств, связанных с СП, ПТСР занимает особое и, в некотором смысле, suicide attempt (SA), which may end in death [1, 2]. At the same time, not everyone who suffers from mental health disorders attempts suicide. This raises the question of the factors that determine suicide risk in mental disorders, as well as which disorders are more commonly associated with suicide or SA and to what extent they increase risk. Depression and various addictions are the most common diagnoses found in those who get engaged in non-fatal suicidal behavior (SB) and are admitted to general medical facilities, with psychosis and personality disorders being somewhat less common [3]. Adaptation disorders and acute situational reactions are also detected in a significant proportion of persons who attempt suicide [4]. It is interesting to note that according to the data from domestic studies, PTSD is very rarely mentioned in this list.

The main factors that drive psychiatric patients to suicide are determined by the suffering associated with the disorder itself, namely social maladjustment, reduced life quality, feelings of dissatisfaction with life, stigmatization and self-stigmatization, frequently experienced subjective feelings of distress, inability to function, problems with one’s environment, and social problems in more general terms [1]. At the same time, the same mental health problems may stem from a number of temperament, behavioral and personality traits inherent to both psychiatric patients and healthy individuals, and are also relevant as predisposing factors for suicidality [5]. In other words, psychiatric disorders increase the risk of SB not only by themselves, but also through a variety of psychopathological disorders that need to be identified in other ways, using appropriate psychometric tools. These traits and behavioral characteristics such as neuroticism, impulsivity, hostility, aggressiveness, anger, introversion, risk-taking, self-regulation problems, etc. [6]. These same traits are often considered as psychopathological manifestations of stress-diathesis, which has deep neurobiological roots and which underlies both PTSD and a number of other disorders and, ultimately, suicidal behavior [7, 8].

Among mental disorders associated with SB, PTSD occupies a special and, to some extent, ambiguous place. On the one hand, epidemiologic studies suggest that a

неоднозначное место. С одной стороны, эпидемиологические исследования свидетельствуют о том, что диагноз ПТСР существенно повышает риск СП [7, 9]. С точки зрения психобиологии ПТСР и суицидальное поведение могут иметь общие нейробиоло-гические механизмы, связанные со стресс-уязвимостью (стресс-диатезом) [7, 10]. В то же время, ПСТР как уникальное расстройство, возникающее только при столкновении с исключительно сильным угрожающим жизни событием с последующей фиксацией эмоции страха, резко ухудшает качество жизни пациента, создавая множество проблем в самых разных сферах (нарушения эмоциональной сферы, потеря социального статуса, разлад в интимных отношениях, тревога и депрессивные переживания в связи со своим состоянием, потребление алкоголя, гемблинг, проблемы с трудоустройством, с законом и т.д.). [11]. Уже в силу этого ПТСР может стать серьёзным фактором суицидального поведения, особенно если учесть, что хронизация травмы часто сопровождается ещё и нарушениями соматического здоровья [12].

В то же время, клинические наблюдения, например, когда пациенты с ПТСР, поступающие на лечение или реабилитацию, опрашиваются на предмет суицидальных мыслей и попыток, или, когда данные эпидемиологических опросов о СП сопоставляются с психиатрическим статусом, дают неоднородные результаты. Так, среди, пожалуй, самого обследованного на предмет ПТСР контингента в мире – ветеранов военных конфликтов США – данные исследований противоречивы и разнятся. По итогам систематического обзора, из 16 исследований, в которых корректно оценивали ассоциацию ПТСР с суицидальными мыслями и попытками, семь не выявили никакой связи, а в трёх диагноз ПТСР был ассоциирован со сниженным риском суицида [12]. Таким образом, несмотря на то, что наличие диагноза ПТСР, как правило, означает повышение риска суицида [7, 11, 12], возможны и противоположные эффекты, которые могут быть связаны с особенностями личности пациентов, в том числе с природной устойчивостью к травме, посттравматическим ростом, то есть с приобретением новых качеств в условиях стресса, выраженностью антисуицидальных барьеров или с иными обстоятельствами, которые ещё предстоит понять [13, 14]. Кроме того, далеко не все пациенты с ПТСР из-за своего заболевания теряют связи со своим окружением и обществом в целом, многое зависит от степени их социальной адаптации, diagnosis of PTSD significantly increases the risk of SB [7, 9]. From a psychobiological perspective, PTSD and suicidal behavior may share common neurobiological mechanisms related to stress vulnerability (stressdiathesis) [7, 10]. At the same time, PSTD as a unique disorder that develops after an exceptionally strong life-threatening event with subsequent fixation of the emotion of fear, dramatically impairs the patient's quality of life. It creates a multitude of problems in a variety of areas (emotional disturbances, loss of social status, discord in intimate relationships, anxiety and depressive experiences due to one's condition, alcohol consumption, gambling, problems with employment, with the law, etc.) [11]. Already due to this, PTSD can become a serious factor of suicidal behavior, especially if we take into account that the chronic trauma is often accompanied by a variety of somatic disorders [12].

At the same time, during clinical observations, for instance when suicidal thoughts and attempts are assessed in PTSD patients entering treatment or rehabilitation, or when SB during epidemiologic surveys is linked to psychiatric status of individuals, the results are heterogeneous. For example, among perhaps the most well-studied PTSD contingent in the world, i.e. U.S. military conflicts veterans, survey data are inconsistent and varied. In a systematic review, of the 16 studies that correctly assessed the association of PTSD with suicidal thoughts and attempts, seven found no association, and in three, PTSD was associated with a reduced risk of suicide [12]. Thus, despite the fact that the presence of PTSD, as a rule, means an increased risk of suicide [7, 11, 12], the opposite effects are also possible, which may be related to the peculiarities of patients' personality, including natural resistance to trauma, posttraumatic growth, i.e., the acquisition of new qualities under stress, the expression of antisuicidal barriers, or other circumstances that have yet to be understood [13, 14]. In addition, not all patients with PTSD lose ties with their environment and society as a whole because of their illness, much depends on the degree of their social adaptation, the availability of social and psychological support, timely psychotherapeutic treatment and many other factors [15]. Another important circum-

наличия социальной и психологической поддержки, своевременного психотерапевтического лечения и многих других факторов [15]. Ещё одним важным обстоятельством является то, что ПТСР – весьма ко-морбидная патология, часто сочетающаяся с такими нарушениями, как депрессия, зависимости, генерализованное тревожное расстройство, каждое из которых может выступать самостоятельной причиной суицидального поведения [16, 17]. Особая роль в этом плане принадлежит тревоге и депрессии, роль которых в суицидальном поведении хорошо известна [3].

Всё это определяет круг не до конца проясненных вопросов в суицидологии в связи таким расстройством как ПТСР. При этом нужно отметить, что данная тема получает большое внимание в последнее время в России, учитывая вероятность увеличения числа пациентов с этим расстройством [18]. За последние 1-2 года число публикаций, посвящённых проблеме ПТСР в отечественной литературе увеличилось, однако в основном это обзорные работы, в которых обсуждается патогенез и лечение этого расстройства, как правило, по результатам западных исследований [19]. Опубликованные недавно клинические методические рекомендации охватывают все вопросы диагностики, лечения и реабилитации пациентов с ПТСР, но почти не касаются проблемы суицидального поведения при ПТСР, ограничиваясь указаниями о необходимости оценки риска суицида в клинических условиях [20].

Нужно также отметить, что большинство исследований, посвященных роли ПТСР как фактора суицидального поведения, опубликованы зарубежом, то есть в среде, не вполне адекватной культуре народов, населяющих Россию. В то же время, переживание травмы, её повреждающее действие, резистентность к ней, сопутствующие суицидальные тенденции, как известно, испытывают сильное влияние этно-культуральных факторов [21-23]. В отечественной литературе, по сути, отсутствуют исследования, которые бы осветили роль личностных особенностей и культурно-обусловленных психологических конструктов, например, таких как безнадёжность (ощущение отсутствия перспектив) и намеренность в момент суицидальных действий, в контексте суицидального поведения при ПТСР. Эти вопросы особенно важны применительно к гражданским лицам, которые, как показывают многочисленные наблюдения, наиболее уязвимы в плане травматизации в условиях военных конфликтов, природных катастроф и массовых стрессовых ситуаций [24, 25].

stance is that PTSD is a very comorbid pathology, often combined with such disorders as depression, addictions, generalized anxiety disorder, each being potential independent cause of SB [16, 17]. A special role in this regard belongs to anxiety and depression, which are known risk factors of suicidal behavior [3].

All this determines the range of not fully clarified issues in suicidology regarding such a disorder as PTSD. At the same time, it should be noted that this topic has recently received a lot of attention in Russia, given the probability of an increase in the number of patients with this disorder [18]. Over the last 1-2 years, the number of publications devoted to the problem of PTSD in the Russian literature has increased, but these are mostly review papers discussing the pathogenesis and treatment, usually based on the results of Western studies [19]. Recently published national clinical guidelines cover all issues of diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation of patients with PTSD, but they only slightly address the problem of suicidal behavior in this context, limiting themselves to advocating the need for suicide risk assessment in clinical settings [20].

It should also be noted that most studies on the role of PTSD as a factor of SB have been published abroad, i.e. in an environment that is not quite adequate to the culture of the peoples inhabiting Russia. At the same time, the experience of trauma, its damaging effects, resilience to it, as well as concomitant suicidal tendencies are known to be strongly influenced by ethno-cultural factors [21-23]. There is an essential lack of studies in the domestic literature that would highlight the role of personality traits and culturally conditioned psychological constructs, for example, such as hopelessness (feeling of lack of prospects in life), and intentionality of suicidal act in the context of suicidal behavior in PTSD. These issues are particularly important for civilians, who have been consistently reported to be the most vulnerable to traumatization in military conflicts, natural disasters, and mass stressors [24, 25].

In this regard, it is necessary to pay attention to the psychological factors of suicide inherent in men and women, taking into account their differential sensitivity to

В этой связи необходимо уделить внимание психологическим факторам суицидогенеза, присущим мужчинам и женщинам, с учётом их различающейся чувствительности к травматическому стрессу, вероятности возникновения ПТСР и склонности к совершению СП [11, 19, 20]. Такая информация, как нам представляется, была бы полезна не только для понимания глубинных факторов и мотивов нефатального суицидального поведения среди мужчин и женщин в славянской культуре, но и могла бы найти практическое применение при выстраивании мер предупреждения завершённых суицидов среди лиц, совершивших попытки. Соответственно, наибольшее приложение результаты такого исследования могли бы найти среди психиатров, консультирующих пациентов, поступивших в соматические стационары после СП.

Ещё одной сферой применения таких данных могла бы стать область психотерапии ПТСР, осложнённого суицидальными тенденциями, поскольку углублённое понимание личности пациента является залогом успешности психотерапевтических мероприятий в такой ситуации. В этом контексте наиболее ценным является концепция структуры личности, известная как «Большая Пятерка», которая предлагает высокодифференцированное представление личностного профиля по пяти основным шкалам (Нейротизм, Экстраверсия, Открытость опыту, Сотрудничество и Добросовестность) и по тридцати подшкалам, в результате чего личность предстает в многогранном виде [26].

Исходя из вышеизложенного, цель настоящей работы – изучить особенности нефатального суицидального поведения мужчин и женщин с диагнозом ПТСР в сравнении с суицидентами без явных психиатрических расстройств. Основная гипотеза исследования заключалась в следующем: суицидальная попытка на фоне ПТСР отличается большей тяжестью, намеренностью и потенциальной летальностью. Вторичные гипотезы формулируются следующим образом: 1) существуют различия в ключевых характеристиках нефатального суицидального поведения мужчин и женщин на фоне ПТСР; 2) личностные черты, ассоциированные с суицидальным поведением на фоне ПТСР, различаются у мужчин и женщин; 3) такой конструкт суицидального поведения, как безнадёжность, по-разному реализуется в ходе суицидальной попытки у мужчин и женщин на фоне ПТСР.

Материалы и методы

Описание проекта. Данное исследование стало возможным благодаря данным, накопленным при traumatic stress, probability of PTSD, and propensity to commit SA [11, 19, 20]. Such information, to our opinion, would be useful not only for understanding the underlying factors and motives of non-fatal SB among men and women in Slavic culture, but could also find practical application in building measures for preventing completed suicides among suicide attempters. Accordingly, the results of such a study may be utilized by psychiatrists counseling patients who have attempted suicide in somatic hospitals.

Another area of application of such data could be psychotherapy PTSD patients expressing suicidal tendencies, since an in-depth understanding of their personality is a key to successful psychotherapeutic interventions. In this context, the personality structure model known as the Big Five is most valuable, which offers a highly differentiated representation of the personality profile on five major scales (Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness) and thirty subscales, resulting in a multifaceted overview of the individuality [26].

Based on the above, the purpose of this paper is to study the peculiarities of nonfatal suicidal behavior of men and women diagnosed with PTSD in comparison with suicide attempters without any obvious psychiatric disorders. The primary hypothesis of the study was as follows: a suicide attempt against the background of PTSD is characterized by greater severity, intentionality and potential lethality. Secondary hypotheses are formulated as follows: 1) there are differences in key characteristics of nonfatal suicidal behavior of men and women against suffering from PTSD; 2) personality traits associated with suicidal behavior against the background of PTSD differ between men and women; 3) such a construct of suicidal behavior as hopelessness is realized differently in men and women attempting suicide and diagnosed with PTSD.

Materials and methods

Project description. This study became possible due to the data accumulated by the international genetic project GISS (Genetic Study of Suicide and Suicide Attempts), which was carried out in Ukraine in 20002007 in accordance with a specially developed protocol [27]. Within the framework

реализации международного генетического проекта GISS (Genetic Study of Suicide and Suicide Attempts), который выполнялся на Украине в 2000-2007 гг. в соответствии с специально разработанным протоколом [27]. В рамках данного проекта более 1300 семей славянского происхождения (пробанд, совершивший СП, и оба родителя) из разных городов Украины были обследованы с помощью ряда психометрических инструментов и генотипированы. Это позволило собрать выборку сравнительно молодых людей, совершивших суицидальные попытки.

Характеристики выборки. Стратегия проекта GISS была разработана таким образом, чтобы обеспечить сбор культурно и этнически однородной выборки суицидентов с хорошо охарактеризованными СП, которые в то же время были бы разнообразны по методам, медицинским исходам и сопутствующим психиатрическим диагнозам. Для этого подготовленные интервьюеры из 14 крупных городов Украины (клинические психологи или психиатры) обращались к лицам славянского происхождения (одним из условий было русское или украинское происхождение в трех поколениях) в психиатрических больницах, службах скорой помощи, отделениях неотложной помощи больниц общего профиля, психоневрологических диспансерах в разных городах Украины и вовлекали их в исследование. Критериями включения были: 1) возраст старше 14 лет; 2) наличие обоих родителей; 3) факт совершения СП с медицинской степенью тяжести не менее 2 баллов по шкале Бека. Все члены семьи подписывали письма информированного согласия. В настоящее исследование были включены данные о 160 суицидентах с диагнозом ПТСР и о 637 суицидентах без психиатрического диагноза, выявленные в базе данных проекта. Средний возраст выборки (M±σ) составил 23,96±7,84 лет.

Психометрический инструментарий. Пациенты были опрошены в соответствии с протоколом исследования GISS, который включал демографическую часть, вопросы, касающиеся последней (индексной) и предыдущих СП, семейной суицидальной истории, физического здоровья, негативных жизненных событий, а также несколько психометрических тестов и диагностических инструментов [27]. В данном исследовании нами использовались результаты применения следующих шкал и опросников: Шкала медицинской тяжести самоповреждений (MDS) – для оценки летальности попытки с рейтингом от 0 (нет ущерба) до 8 (летальный исход) с поправкой на каждый способ самоповреждения (Х60-Х84) [28]; Шкала of this project, more than 1300 families of Slavic origin (a proband who committed suicide and both parents) from different cities of Ukraine were assessed using a number of psychometric tools and geno-typed. This made it possible to collect a sample of relatively young people who attempted suicide.

Sample characteristics. The GISS project strategy was designed to ensure the collection of a culturally and ethnically homogeneous sample of suicidal individuals with well-characterized SA, which were at the same time diverse in methods, medical outcomes, and concomitant psychiatric diagnoses. For this purpose, trained interviewers from 14 major Ukrainian cities (clinical psychologists or psychiatrists) approached individuals of Slavic origin (one of the conditions was Russian or Ukrainian ancestry in 3 generations) in psychiatric hospitals, emergency services, emergency departments of general hospitals, and psychoneurologic dispensaries in different cities of Ukrainian and involved them in the study. Inclusion criteria were 1) age older than 14 years; 2) presence of both parents; 3) the fact of SA with a medical severity of at least 2 points on the Beck scale. All family members signed informed consent letters. Data on 160 suicides with a diagnosis of PTSD and 637 suicides without a psychiatric diagnosis identified in the project database were included in the present study. The mean age of the sample (M±σ) was 23,96±7,84 years.

Psychometric instrumentation. Patients were interviewed according to the GISS study protocol, which included a demographic part, questions regarding the last (index) and previous SA, family suicidal history, physical health, negative life events, and several psychometric tests and diagnostic tools [27]. In this study, we utilized the results of the following scales and questionnaires: Medical Damage Scale (MDS) - to assess the lethality of the attempt with ratings ranging from 0 (no harm) to 8 (lethal) adjusted for each mode of self-harm (X60-X84) [28]; Beck Suicidal Intent Scale (BSIS) [29]; Beck Depression Scale (BDI) [30]; four questions from the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) for dichotomous assessment of a person as experiencing hopelessness or not [31]; the Plutchik Feelings

суицидальных намерений Бека (BSIS) [29]; Шкала депрессии Бека (BDI) [30]; четыре вопроса из Шкалы безнадёжности Бека (BHS) для дихотомической оценки человека как испытывающего безнадёжность или нет [31]; Шкала склонности к насильственным действиям Плутчика (PFAV) [32]; Шкала характеристик гнева Спилбергера (STAS) [33]; личностный опросник NEO-PIR, русскоязычный вариант [34, 35]. Данные вводили в разработанную для целей проекта GISS информационную систему на базе платформы FileMaker Pro for Windows. Для каждого психометрического инструмента существовала возможность стандартизированного подсчета баллов с помощью специально разработанного программного обеспечения. В случае NEO-PIR программа рассчитывала Т-баллы с учётом возраста и пола испытуемых. Психиатрический диагноз устанавливали с использованием диагностического опросника CIDI 2.0 в компьютерном варианте [36]. Все инструменты представляли собой валидизированные русскоязычные версии или квалифицированно переведенные варианты.

Статистическая обработка данных осуществлялась с использованием программы IBM SPSS Statistics, версия 26. С учётом характера распределения и типа переменных применяли критерий χ2-квадрат Пирсона, точный критерий Фишера, t -критерий Стьюдента или критерий Манна-Уитни. Для проверки распределения на нормальность использовали критерий Шапиро-Уилка.

Результаты и их обсуждение

На первом этапе анализа целесообразно рассмотреть количественные показатели выборки данного исследования с точки зрения психиатрических характеристик (табл. 1). В базе данных, содержащей сведения о 1328 суицидентах, были выявлены 160 человек с диагнозом ПТСР и 637 человек без каких-либо диагнозов. Таким образом, доля суицидентов с ПТСР составила 12,05% от общей выборки, в то время как доля лиц, совершивших СП, не имея при этом психиатрических диагнозов (согласно CIDI 2.0), составила 47,97%. Среди суицидентов доля лиц с ПТСР оказалась заметно больше, чем среди молодых людей в общей популяции, которая оценивается (по зарубежным данным) в пределах 1% среди мужчин и 3% среди женщин [37], и приближается к таковой среди участников боевых действий [38, 39]. Во всей выборке мужчины несколько преобладают (соотношение составило 1,12), при этом доля суицидентов без диагнозов выше среди мужчин (незначимо). В то же время, процент выявленных случаев ПТСР среди and Acts of Violence Scale (PFAV) [32]; the Spielberger Trait Anger Scale (STAS) [33]; and the NEO-PIR personality questionnaire, Russian version [34,35]. Data were entered into an information system based on FileMaker Pro for Windows platform developed specifically for the GISS project. For each psychometric instrument, there was a possibility of standardized scoring using specially developed software. In the case of the NEO-PIR, the program calculated T-scores taking into account the age and sex of the subjects. Psychiatric diagnosis was established using the CIDI 2.0 computerized diagnostic questionnaire [36]. All instruments were validated Russian-language or expertly translated versions.

Statistical processing of the data was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics program, version 26. Taking into account the nature of distribution and type of variables, Pearson's χ2-square test, Fisher's exact test, Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney U test were used. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check the distribution for normality.

Results and discussion

In the first stage of the analysis, it is necessary to describe the quantitative parameters of the sample of the study in terms of psychiatric characteristics (Table 1). In a database containing information on 1328 suicides there were identifies 160 individuals with a diagnosis of PTSD and 637 without any diagnoses. Thus, the proportion of suicides with PTSD was 12,05% of the total sample, while the proportion of persons who committed SA without psychiatric diagnoses (according to CIDI 2.0) was 47,97%. Thus, among suicide attempters, the proportion of individuals with PTSD was noticeably higher than among young people in the general population, which is estimated (according to foreign data) to be within 1% among men and 3% among women [37], and approaching that among combatants [38, 39]. In the entire sample, men slightly predominate (the ratio was 1,12), with the proportion of SA without diagnoses being higher among men (insignificant). At the same time, the percentage of diagnosed PTSD cases among female SA is twice as high as among males (16,64% vs. 7,97%, significant, p <0.001). This coincides with the other studies indicating a higher incidence of PTSD among women

женщин, совершивших СП, вдвое выше чем среди мужчин (16,64% против 7,97%, значимо, р <0,001). Это совпадает с данными литературы, согласно которым среди женщин и на популяционном уровне, и в клинических контингентах наблюдается бόльшая частота ПТСР [40, 41].

Как видно из табл. 1, коморбидность ПСТР наблюдается примерно у половины мужчин и женщин с этим диагнозом (различия незначимы), однако структура этой коморбидности разная. У мужчин более чем в 2 раза преобладают различные зависимости (алкогольная, наркотическая, включая острую интоксикацию), у женщин в 2 раза чаще встречается депрессия и шизофрения.

Среди мужчин и женщин с ПТСР с наибольшей частотой представлены тревожные и связанные со стрессом расстройства, причём у женщин заметно чаще (58,62% против 45,47%).

both at the population level and in clinical samples [40, 41].

As can be seen from Table 1, comorbidity of PSTD is observed in about half of men and women with this diagnosis (the differences are insignificant), but the structure of this comorbidity is different. In men, various addictions (alcohol, drug addiction, including acute intoxication) are more than 2 times more prevalent; in women, depression and schizophrenia are 2 times more common.

Among men and women with PTSD, anxiety and stress-related disorders are most frequent, in women more frequent (58,62% vs. 45,47%). These differences are statistically significant ( p =0.003). At the same time, no significant differences were found in the distribution of multiple diagnoses among men and women who attempted suicide.

Таблица / Table 1

Психиатрический статус лиц с нефатальным суицидальным поведением Psychiatric status of individuals with non-fatal suicidal behavior

|

Психиатрическая патология (n, %)* Psychiatric pathological states |

Мужчины Men n=703 (52,94) |

Женщины Women n=625 (47,06) |

P |

χ2 |

df |

|

Без диагноза (n, % от всей выборки) No diagnosis (n, % from the whole sample) |

328 (46,72) |

309 (49,44) |

0,311 |

1,027 |

1 |

|

Выявлен ПТСР (n, % от всей выборки) Diagnosed PTSD (n, % from the whole sample) |

56 (7,97) |

104 (16,64) |

<0,001 |

23,492 |

1 |

|

Выявлена коморбидность (n, % от всех с ПТСР) Diagnosed comorbidity (n, % of those with PTSD) |

27 (48,21) |

52 (50,00) |

0,830 |

0,046 |

1 |

|

Коморбидные диагнозы (n, % от общего числа) Comorbid diagnoses (n, % of the whole number) F10-F19 (зависимости, addictions) F20-F29 (шизофрения и психозы, schizophrenia and psychoses) F30-F39 (депрессия, depression) F40-F48 (тревожные и стрессовые р-ва, anxiety and stress disorders) F50-F59 (расстройства пищевого поведения, eating disorders) |

32 (40,51) 2 (2,53) 8 (10,13) 36 (45,57) 1 (1,27) |

18 (15,52) 6 (5,17) 23 (19,82) 68 (58,62) 1 (0,86) |

0,003 |

16,601 |

4 |

|

Число суицидентов с множественными диагнозами (n, % от числа коморбидных) Number of suicide attempters with comorbid diagnoses (n, % from comorbidities)

9-11 диагнозов (9-11 diagnoses) |

12 (44,44) 7 (25,93) 1 (3,70) 1 (3,70) 1 (3,70) 3 (11,11) 0 (0,00) 0 (0,00 2 (7,41) |

21 (40,39) 14 (26,92) 10 (19,23) 3 (5,77) 2 (3,85) 0 (0,00) 1 (1,92) 1 (1,92) 0 (0,00) |

p>0,05 |

13,973 |

8 |

Примечание / Notes: *Использован метод χ2

Эти различия статистически значимы ( p =0,003). В то же время, значимых различий в распределении суицидентов с множественными диагнозами среди мужчин и женщин не выявлено. Чаще всего встречались 1-2 дополнительных диагноза, реже 4 и более диагноза.

Следует отметить, что по данным исследований в России среди лиц, совершивших СП, чаще всего встречаются невротические, связанные со стрессом и соматоформные расстройства, однако ПТСР наблюдается редко [42, 43]. Нужно, однако, иметь в виду, что опросник CIDI 2.0 не позволяет выявлять личностные расстройства, наличие которых нельзя исключить как среди пациентов с ПСТР, так и среди тех, кто совершил СП на фоне отсутствия психиатрических диагнозов. В то же время, формальное следование результатам этого опросника приводит к множественным диагнозам, что отражено в табл. 1. При этом наличие среди суицидентов психически здоровых лиц также не вызывает удивления. Данные из разных стран свидетельствуют о том, что значительная (от 20 до 50%) часть СП совершается на фоне отсутствия психической патологии. Это имеет место и в России, и в США, и в Китае [44-46]. Таким образом, наша выборка вполне отражает тенденции психиатрической патологии среди лиц, совершающих СП. Мы не можем судить, является ли диагноз ПТСР первичным по отношению ко всем остальным, или наоборот, сопутствующим и приобретённым позже.

На следующем этапе мы проанализировали основные демографические показатели группы суици-дентов с ПТСР и без диагнозов (табл. 2).

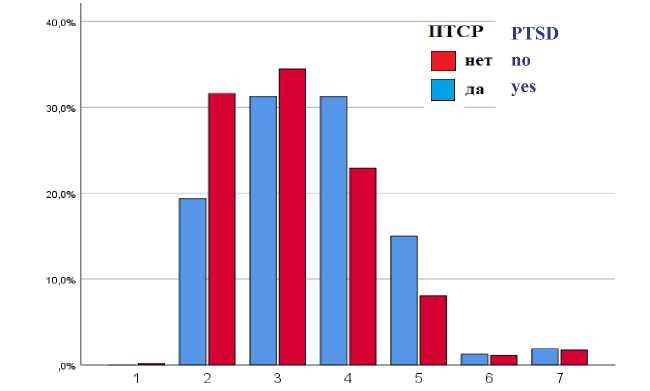

Как видно из табл. 2, значимые различия касались только соотношения между мужчинами и женщинами – среди суицидентов с ПТСР доля последних была больше. В связи с этим, все остальные показатели суицидального поведения анализировались нами раздельно для мужчин и женщин. Перед этим мы проверили, существуют ли различия в тяжести СП среди всех суицидентов с ПТСР по сравнению с суициден-тами без диагнозов. Попытки, совершённые суици-дентами с ПТСР (суммарно мужчинами и женщинами), оказались значимо более тяжёлыми (χ2=17,347; p=0,008). Как следует из рис. 1, наибольшие отличия касаются достаточно тяжёлых попыток, со степенью тяжести 4 и 5 (при ПТСР они встречаются в 1,5-2 раза чаще) и лёгких попыток со степенью тяжести 2 (при ПТСР они встречаются в 1,5 раза реже).

В связи с этим целесообразно рассмотреть, как это связано с различиями нефатального суицидального поведения мужчин и женщин.

Most often 1-2 additional diagnoses were found, less frequently 4 or more diagnoses.

It should be noted that according to Russian studies, neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders are the most common among those who attempt suicide, while PTSD is quite rarely observed [42, 43]. It should be kept in mind, however, that the CIDI 2.0 questionnaire does not allow the identification of personality disorders, the presence of which cannot be excluded both among patients with PTSD and among those who committed SA without psychiatric diagnoses. At the same time, formal adherence to the results of this questionnaire leads to multiple diagnoses, which is reflected in Table 1. It should be noted that the presence of mentally healthy persons among suicide attempters is also not surprising. Data from different countries show that a significant (from 20% to 50%) part of suicides is committed by those who have no psychiatric pathology. This is the case in Russia, the USA, and China [44-46]. Thus, our sample quite reflects the trends of psychiatric pathology among persons committing SA. We cannot judge whether the diagnosis of PTSD is primary in relation to all other diagnoses or, on the contrary, concomitant and acquired later.

In the next step, we analyzed the basic demographics of the suicide attempters with and without PTSD diagnoses (Table 2).

As can be seen from Table 2, significant differences were revealed regarding the ratio between men and women – the proportion of the latter was higher among suicide attempters with PTSD. Therefore, further we analyzed all other indicators of suicidal behavior separately for men and women. Preliminary we checked whether there were differences in the severity of SA among all attempters with PTSD as compared to those without diagnoses. Attempts made by individuals with PTSD (men and women together) were found to be significantly more severe (χ2=17,347; p =0.008). As Fig. 1 shows, the greatest differences were in fairly severe attempts with MDS scores 4 and 5 (1,5-2 times more frequent in PTSD) and mild attempts with MDS level 2 (1,5 times less frequent in PTSD).

Therefore, it is reasonable to look how this relates to differences in non-fatal suicidal behavior between men and women.

Таблица / Table 2

Основные демографические характеристики суицидентов с ПТСР в сравнении с суицидентами без психиатрических диагнозов

Main demographic features of PTSD suicide attempters in comparison with those without psychiatric diagnoses

Рис. 1. Диаграмма, отображающая соотношение СП с различной степенью тяжести среди лиц с ПСТР и без диагнозов / Fig. 1. Chart of the proportion of SA with varying degrees of severity among individuals with and without PSTD diagnoses.

тяжесть medical severity

|

Переменные Variables |

Суициденты с ПТСР Suicide attempters with PTSD (n=160) |

Суициденты без диагнозов Suicide attempters without diagnoses (n=637) |

p |

χ2 |

df |

|

Женщины, n (%)* Women, n (%)* |

104 (65,00) |

309 (48,51) |

<0,001 |

13,930 |

1 |

|

Мужчины, n (%)* Men, n (%)* |

56 (35,00) |

328 (51,49) |

|||

|

Возраст, медиана (Q1; Q3)** Age, median, (Q1; Q3)** |

23 (19; 28) |

22 (18; 28) |

0,286 |

||

|

Женат / замужем / Married, n (%)* Вдова / вдовец / Widowed, n (%)* Расстались / Separated, n (%)* В разводе / Divorced, n (%)* Не был/а женат/замужем / Never married, n (%)* |

24 (15,00) 2 (1,25) 12 (7,50) 17 (10,63) 105 (65,63) |

90 (14,12) 9 (1,41) 28 (4,40) 48 (7,54) 462 (72,52) |

0,298 |

4,901 |

4 |

|

Число детей на 1 чел., среднее (Min; Max)** Number of children per person (Min; Max)** |

0,35 (0; 2) |

0,29 (0; 4) |

0,0840 |

||

|

Число лет учёбы, среднее (Q1; Q3)** Number of years of schooling (Q1; Q3)** |

11,5 (10; 14) |

11 (10; 13) |

0,528 |

||

|

Работают, n (%)* Employed, n (%)* |

62 (38,75) |

286 (44,89) |

0,161 |

1,965 |

1 |

|

Не работают, n (%)* Unemployed, n (%)* |

98 (61,25) |

351 (55,10) |

|||

|

Число месяцев безработицы за последний год, среднее (Min; Max)** Number of months of unemployment for the last year, mean (Min; Max)** |

5,15 (0; 12) |

5,71 (0; 12) |

0,347 |

Примечание: *тест χ2; **тест Манна-Уитни / Notes: * χ2 test; **Mann-Whitney U test

Как видно из таблицы 3, характеристики нефатального суицидального поведения у мужчин и женщин существенно различаются: мужчины (независимо от наличия или отсутствия психиатрических

As can be seen from Table 3, the characteristics of non-fatal SB differ significantly between men and women: men (regardless of the presence or absence of psychiat- диагнозов) примерно вдвое чаще используют более насильственные и травматичные способы совершения СП, в то время как женщины в 2 раза чаще используют самоотравления. В данном случае группирование способов как ненасильственных и насильственных осуществляется по принципу «все отравления» против «порезы и другие механические способы» [47]. При этом диагноз ПТСР никак не влияет на соотношение избираемых способов среди мужчин, в то время как среди женщин приводит к значимому (р=0,029) увеличению доли насильственных методов. Иными словами, женщины с ПТСР, совершая СП, ведут себя «немного как мужчины».

ric diagnoses) are about twice as likely to use more violent and traumatic methods of committing suicide, while women are twice as likely to use self-poisoning. In this case, the grouping of methods as nonviolent and violent is based on the principle of “all poisonings” versus “cutting and other mechanical means” [47]. At the same time, the diagnosis of PTSD had no effect on the ratio of selected methods among men, but among women it led to a significant ( p =0.029) increase in the share of violent methods. In other words, women with PTSD behave “a bit like men” when attempting suicide.

Таблица / Table 3

Характеристики суицидальных попыток и намеренность суицидального акта у мужчин и женщин, совершивших СП на фоне ПТСР в сравнении с суицидентами без диагнозов

Suicide attempt characteristics and suicidal intent in male and female suicide attempters with PTSD and without diagnoses

|

Мужчины / Men |

|||

|

Показатели СП и намеренности SA and intention indicators |

ПТСР PTSD (n=56) |

Без диагнозов No diagnoses (n=328) |

p |

|

СП путём самоотравления, (X60-X69), n (%)* SA by self-intoxication, (X60-X69), n (%)* |

18 (32,1) |

113 (34,5) |

0,763 |

|

СП путем самопорезов и др. способами, (X70-X84), n (%)* SA by self-cutting and other methods, (X70-X84), n (%)* |

38 (67,9) |

215 (65,5) |

|

|

Медицинская тяжесть попытки, средняя, медиана, Q1; Q3** Medical severity of SA, mean, median, Q1; Q3** |

3,70; 3 (3;5) |

3,10; 3 (2;4) |

0,001 |

|

Намеренность (подготовительные действия), медиана, Q1; Q3** Intent (preparatory measures), median, Q1; Q3** |

15 (12; 16) |

13 (11; 16) |

0,025 |

|

Намеренность (субъективно), медиана, Q1; Q3** Intent (subjective), median, Q1; Q3** |

7 (5,25; 9) |

6 (4; 7) |

0,002 |

|

Намеренность (суммарная), медиана, Q1; Q3** Intent (total), median, Q1; Q3** |

21,5 (18; 24) |

19 (17; 22) |

0,001 |

|

Женщины / Women |

|||

|

Показатели СП и намеренности SA and intention indicators |

ПТСР PTSD (n=104) |

Без диагнозов No diagnoses (n=309) |

p |

|

СП путём самоотравления (X60-X69), n (%)* SA by self-intoxication, (X60-X69), n (%)* |

71 (68,3) |

241 (78,0) |

0,029 |

|

СП путём самопорезов и др. способами (X70-X84), n (%)* SA by self-cutting and other methods, (X70-X84), n (%)* |

33 (31,7) |

68 (21,0) |

|

|

Медицинская тяжесть попытки, средняя, медиана** Medical severity of SA, mean, median, Q1; Q3** |

3,44; 4 (3; 4) |

3,25; 3 (2; 4) |

0,044 |

|

Намеренность (подготовительные действия), медиана, Q1; Q3** Intent (preparatory measures), median, Q1; Q3** |

14 (13; 16) |

14 (11,75; 15) |

0,017 |

|

Намеренность (субъективно), медиана, Q1; Q3** Intent (subjective), median, Q1; Q3** |

7 (5; 9) |

6 (4; 8) |

0,000 |

|

Намеренность (суммарная), медиана, Q1; Q3** Intent (total), median, Q1; Q3** |

21 (19; 23) |

19 (17; 23) |

0,000 |

Примечание: *Точный критерий Фишера; ** тест Манна-Уитни / Notes: *Fisher exact test; **Mann-Whitney U test

Что касается степени тяжести и намеренности СП, то и мужчины, и женщины с ПТСР демонстрируют более высокую намеренность и тяжесть попыток, все различия значимы (табл. 3). Особое значение имеет фактор намеренности. Согласно опроснику Бека [29] намеренность в момент совершения СП оценивается по двум критериям – косвенно, как осуществление ряда подготовительных действий (запереть или оставить открытыми двери, ограничить, или наоборот, поддерживать с кем-то контакт, сообщить или не сообщать о своих намерениях), и прямо, как изложение своих намерений (чего хотел добиться, ожидал ли наступления смерти, насколько вероятным казался смертельный исход и т.д.). По обоим компонентам у суицидентов с ПТСР, как мужчин, так и женщин, намеренность была значимо выше, что сопровождалось более тяжёлыми СП.

Необходимо также отметить, что наблюдалась тенденция к большей тяжести СП среди мужчин с ПСТР по сравнению с женщинами с ПТСР, и тенденция к большей тяжести среди женщин без диагнозов по сравнению с мужчинами (обе – незначимо). Намеренность среди мужчин и женщин в обеих группах была практически одинаковой (табл. 3).

Хотя во многих работах и обзорах приводятся данные о том, что ПТСР повышает риск суицидального поведения, непосредственное упоминание о намеренности как о факторе, способствующем тяжести СП при ПТСР, нами не обнаружено. В то же время, фактор намеренности является исключительно важным с точки зрения правильной идентификации нефатального суицидального поведения, установления его мотивов и опасности в плане последующего суицида. Наше предыдущее исследование, основанное на ограниченной выборке из базы проекта GISS, показало, что даже такой изолированный конструкт шкалы намеренности Бека, как ожидаемая вероятность наступления смерти, имеет большое значение и зависит от разных факторов риска у мужчин и женщин [48].

В связи с этим интерес представляют психологические и психосоциальные характеристики мужчин и женщин, совершивших СП на фоне ПТСР (табл. 4). Данные таблицы 4 очень красноречивы – если среди мужчин с ПТСР склонность к насильственным действиям, депрессия, гнев и безнадёжность не отличаются от таковых у мужчин без диагнозов, то среди женщин наблюдается противоположная картина: все эти показатели на фоне ПТСР значимо более выражены.

As for the severity and intent of SA, both men and women with PTSD demonstrate higher intentionality and medical severity of attempts, all differences being significant (Table 3). The factor of intent is of particular importance. According to Beck's questionnaire [29], intent at the moment of committing SA is assessed by two criteria – indirectly, as a number of preparatory actions (locking or leaving doors open, limiting or on the contrary, maintaining contact with someone, communicating or not communicating one's intentions), and directly, as the statement of one's intentions (what one wanted to achieve, whether one expected death to occur, how likely the lethal outcome was perceived, etc.). On both components, intent was significantly higher in both men and women with PTSD, which was accompanied by more severe medical outcomes of SA in them.

It should also be noted that there was a trend toward greater severity of SA among men with PSTD compared to women with PTSD, and a trend toward greater severity among women without diagnoses compared to men (both insignificant). Intentionality among men and women was nearly identical in both groups (Table 3).

Although many studies and reviews have reported that PTSD increases the risk of suicidal behavior, we found no direct mention of intentionality as a factor contributing to the severity of SA in PTSD. At the same time, the factor of intentionality is extremely important in terms of correctly identifying nonfatal suicidal behavior, establishing its motives and the risk for subsequent suicide. Our previous study, based on a limited sample from the GISS project database, showed that even such an isolated construct of the Beck Suicide Intent Scale – the expected fatality of SA is of great importance and has different risk factors in men and women [48].

In this connection, psychological and psychosocial characteristics of men and women who attempted suicide against the background of PTSD are of interest (Table 4). The data of Table 4 are very eloquent – while among PTSD men the propensity to violent actions, depression, anger and hopelessness do not differ from those of men without diagnoses, the opposite picture is observed among women: all these indicators are significantly more pronounced.

Таблица / Table 4

Психологические и психосоциальные характеристики мужчин и женщин, совершивших СП на фоне ПТСР в сравнении с суицидентами без диагнозов

Psychological and psychosocial characteristics of male and female suicide attempters with and without PTSD

Данное обстоятельство может быть связано с особенностями личности женщин и мужчин в нашей выборке, которые и предопределяют характеристики суицидального поведения в связи с посттравматическим состоянием. Результаты оценки особенностей личности в рамках модели Большая Пятерка представлены в таблице 5.

Как видно из табл. 5 мужчины-суициденты с ПТСР значимо отличались от «условно здоровых» мужчин по целому ряду личностных черт. В частности, для них характерны пониженные Настойчивость, Активность и Позитивные Эмоции (эти подшкалы принадлежат базовой шкале Экстраверсия).

the diagnosis of PTSD among suicidal women is combined with more pronounced psychological deformations, anger, pessimism, depression and a tendency to violent behavior. Of particular importance is the more frequently experienced sense of hopelessness in them, meaning a negative attitude to the future, fatality, despair, lack of motivation and destroyed life scenario [49].

These findings may be related to the personality characteristics of women and men in our sample, which predetermine the characteristics of suicidal behavior in connection with posttraumatic state. The results of the assessment of personality traits within the framework of the Big Five model are presented in Table 5.

As can be seen from Table 5, male suicide attempters with PTSD significantly differed from “conditionally healthy” men in a number of personality traits.

Таблица / Table 5

Черты личности суицидентов с ПТСР и без диагнозов согласно модели «Большая Пятерка», различающиеся у мужчин и женщин (приведены только значимые отличия) “Big Five” traits differentiating male and female suicide attempters with and without PTSD (only significant differences)

Мужчины / Men

|

Черты Большой Пятерки Big Five traits |

ПТСР PTSD (n=56) |

Без диагнозов No diagnoses (n=328) |

p |

|

ТE3 – Настойчивость, M (SD)* ТE3 – Assertiveness, M (SD)* |

43,38 (9,28) |

46,75 (10,45) |

0,025 |

|

ТE4 – Активность, среднее (Q1; Q3)** ТE4 – Activity, mean, (Q1; Q3)** |

43 (37,25; 51,50) |

48 (39; 53) |

0,028 |

|

ТE6 – Позитивные Эмоции, среднее (Q1; Q3)** ТE6 – Positive Emotions, mean, (Q1; Q3)** |

44 (36; 52) |

48 (41; 54) |

0,037 |

|

ТA1 – Доверие, M (SD)* TA1 – Trust, M (SD)* |

44,16 (10,77) |

47,13 (10,08) |

0,044 |

|

ТA5 – Скромность, M (SD)* TA5 – Modesty, M (SD)* |

52,82 (7,93) |

50,38 (10,53) |

0,046 |

|

ТA6 – Чуткость, среднее, (Q1; Q3)** TA6 – Tender-Mindedness, mean, (Q1; Q3)** |

44,5 (39; 54) |

51 (41; 57) |

0,013 |

Женщины / Women

|

Черты Большой Пятерки Big Five traits |

ПТСР PTSD (n=104) |

Без диагнозов No diagnoses (n=309) |

р |

|

ТN2 – Враждебность, среднее (Q1; Q3)** TN2 – Angry Hostility, mean (Q1; Q3)** |

57 (49; 64) |

52 (47; 60) |

0,012 |

|

ТA – Сотрудничество, среднее (Q1; Q3)** TA – Agreeableness, mean, (Q1; Q3)** |

45 (35; 54) |

48 (41; 55) |

0,042 |

|

ТA2 – Честность, среднее (Q1; Q3)** TA2 – Straightforwardness, mean, (Q1; Q3)** |

47 (38; 52,75) |

50 (42,5; 54) |

0,013 |

Примечание: * t-тест Стьюдента; ** U-критерий Манна-Уитни / Notes: *Student’s t-test; **Mann-Whitney U test

Кроме того, они характеризуются такими сниженными чертами, как Доверие и Чуткость, и повышенной чертой Скромность (эти подшкалы принадлежат базовой шкале Сотрудничество). Иная картина наблюдается среди женщин-суициденток с ПСТР – у них по сравнению с «условно здоровыми» суици-дентками наблюдается значительно более высокая Враждебность (подшкала Нейротизма) и сниженные Сотрудничество (базовая шкала) и Честность (подшкала из этой же шкалы).

Обсуждая эти результаты, необходимо принимать во внимание, что все участники данного исследования совершили СП, что обычно сопряжено с определёнными особенностями личностной структуры, в том числе, в рамках модели Большая Пятёрка. В ряде исследований ранее было показано, что при сравнении со здоровыми контролями лица с СП более всего отличались от здоровых контролей по показателям Нейротизма, Экстраверсии / Интроверсии и Сотрудничества [50, 51]. В частности, среди подростков суицидальное поведение было ассоциировано с повышенными баллами Нейротизма, Открытости опыту и Сотрудничества, и сниженными баллами Экстраверсии и Добросовестности [51]. Высокий уровень Нейротизма и низкий уровень Добросовестности у студентов характерны для нарушений психического здоровья в целом [52].

Ценность наших данных особенно велика для понимания личности суицидентов с ПСТР. Очевидно, что эти личностные характеристики неодинаковы у мужчин и женщин, и заключаются в том, что мужчины с СП и ПТСР ещё более интровертированы, безинициативны (сниженная подшкала Активность) и несчастны (сниженная подшкала Позитивные эмоции), чем суициденты в целом, ещё более циничны и скептичны, а также лишены сострадания по отношению к другим (сниженные подшкалы Доверие и Чуткость). В то же время, они более робки и застенчивы (повышенная подшкала Скромность). Интересно, что среди этих черт у мужчин не оказалось Нейротизма и его подшкал. В то же время, повышенная Враждебность как подфактор Нейротизма оказалась дифференцирующим признаком среди женщин, вместе со сниженным фактором Сотрудничество и такой его подшкалой как Честность (табл. 5).

Эти данные говорят о том, что суициденты с ПТСР имеют свои, весьма характерные личностные черты, отличающие их от суицидентов без диагнозов, причём неожиданно разные среди мужчин и женщин. Так, если по данным ранее проведённого

In particular, they are characterized by lower Assertiveness, Activity, and Positive Emotions (subscales belonging to the basic Extraversion dimension). In addition, they are characterized by such reduced traits as Trust and Tender-Mindedness, and increased trait Modesty (these subscales belong to the basic dimension Agreeableness). A different picture is observed among female attempters with PSTD – compared to “conditionally healthy” female attempters, they have significantly higher Angry Hostility (Neuroticism subscale) and decreased Agreeableness (basic dimension) and Straightforwardness (subscale from the same dimension).

When discussing these results, it should be taken into account that all participants in this study were suicide attempters, which is usually associated with certain features of personality, including the Big Five model. A number of studies have previously shown that, when compared to healthy controls, individuals with SP differed most on measures of Neuroticism, Extraversion / Introversion, and Agreeableness [50,51]. Specifically, among adolescents, suicidal behavior was associated with elevated scores of Neuroticism, Openness to Experience, and Agreeableness, and reduced scores of Extraversion and Conscientiousness [51]. High levels of Neuroticism and low levels of Conscientiousness in students are characteristic of mental health disorders in general [52].

The value of our data is particularly important for understanding the personality of suicidal individuals with PSTD. It is evident that these personality characteristics differ between men and women, that men with SA and PTSD are even more introverted, uninitiated (reduced Activity subscale), and unhappy (reduced Positive Emotions subscale) than suicide attempters in general, even more cynical and skeptical, and lack compassion for others (reduced Trust and Tender-Mindedness subscales). At the same time, they are more timid and shy (increased Modesty subscale). Interestingly, Neuroticism and its subscales were not found among these traits in men. At the same time, increased Angry Hostility as a subfactor of Neuroticism turned out to be a differentiating trait among women, together with a decreased Agreeableness and its subscale Straightforwardness (Table 5).

нами исследования мужчины с СП отличались от здоровых контролей в основном негативной эмоциональностью, то есть различными компонентами Нейротизма [53], то среди суицидентов с ПТСР повышенная Враждебность оказалась более характерна для женщин. Данное обстоятельство хорошо согласуется с тем, что среди женщин с ПТСР были сильнее выражены склонность к насильственным действиям и гнев. В то же время, и мужчины и женщины с ПТСР сохранили ранее выявленные черты в доменах сниженной Экстраверсии и Сотрудничества, но еще более выраженные, чем среди суицидентов без диагнозов. Таким образом, в основном суициденты с ПТСР имеют черты, характерные для лиц с попытками, но более выраженные, заостренные в ещё большей степени. При этом женщины с ПТСР имеют дополнительные особенности в виде повышенной Враждебности и пониженной Честности. Люди с такой характеристикой, на фоне негативной эмоциональности, склонны к манипуляциям и хитрости, могут преувеличивать или, наоборот, скрывать свои чувства [54].

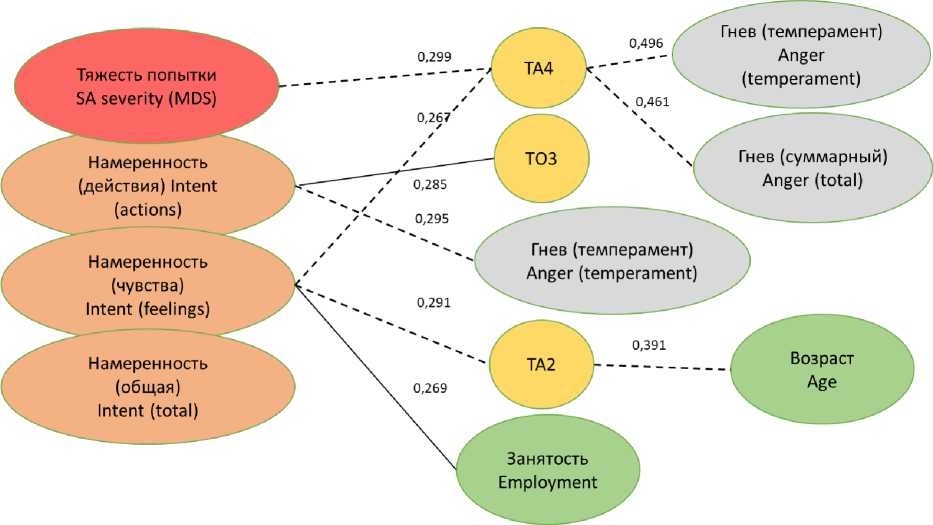

На заключительной стадии нами был проведен корреляционный анализ, который позволил оценить взаимосвязи между основными показателями суицидального поведения (тяжесть и намеренность СП) и психосоциальными и личностными характеристиками мужчин и женщин с ПТСР. В данном случае мы использовали следующий приём: были рассмотрены значимые ( р <0,05) и максимальные по силе ассоциации тяжести СП и намеренности (в виде действий, чувств и суммарно), после чего были проанализированы значимые ассоциации найденных переменных с другими переменными (рис. 2-3).

Как видно из представленных данных, тяжесть и намеренность СП у мужчин связаны с их чертами личности слабыми связями, едва приближающимися к порогу средней силы ( r =0,30) [55]. Большинство корреляций носят обратный характер. Тяжесть попытки имеет одну обратную связь с характеристикой ТА4 – Уступчивость. Согласно трактовке, в своих низших проявлениях эта черта означает крайнюю неуступчивость, то есть соревновательность или агрессивность [54].

Намеренность по шкале Бека, в частности, её поведенческий компонент, оказалась положительно ассоциирована с чертой ТО3 – Чувства. Лица с такой выраженной характеристикой переживают как счастье, так и несчастье более эмоционально, часто поглощены своими эмоциями [54].

These data suggest that suicide at-tempters with PTSD exhibit highly characteristic personality traits that distinguish them from suicide attempters without diagnoses, which appeared to be unexpectedly different among men and women. Thus, if our earlier study has shown that men with PTSD differed from healthy controls mainly by negative emotionality, i.e., various components of Neuroticism [53], among suicide attempters with PTSD increased Angry Hostility was more characteristic of women. This fact agrees well with the fact that tendency to violence and higher anger were more pronounced in them. At the same time, both men and women with PTSD retained the previously identified traits in the domains of reduced Extraversion and Agreeableness, but even more pronounced than among suicidal individuals without diagnoses. Thus, suicidal individuals with PTSD have traits characteristic of individuals with suicide attempts, but more pronounced, sharpened to an even greater degree. At the same time, women with PTSD have additional features, i.e. increased Angry Hostility and decreased Straightforwardness. People with such traits, especially together with negative emotionality, are prone to manipulation and cunning, may exaggerate or, on the contrary, hide their feelings [54].

At the final stage, we used a correlation analysis to assess the relationships between the main indicators of suicidal behavior (severity and intent of SA) and psychosocial and personality characteristics of men and women with PTSD. In this case, we used the following technique: we considered significant ( p <0.05) and strongest associations of MDS and intentionality (in the form of actions, feelings, and total), after which we analyzed the significant associations of the found variables with other variables (Fig. 2-3).

As can be seen from the presented data, the severity and intentionality of SA in men are weakly associated with their psychological characteristics, correlations barely approaching the threshold of medium level ( r =0.30) [55]. Most of the correlations are inverse in nature. The severity of the attempt has one inverse correlation with the TA4 characteristic – Compliance.

Рис. 2. Наиболее выраженные по силе и значимые ( p <0,05) корреляционные связи тяжести и намеренности СП с переменными, характеризующими мужчин-суицидентов с ПТСР / Fig. 2. The strongest and significant ( p <0,05) correlations of SA medical severity and intent with variables featuring male suicide attempters.

В то же время, намеренность как сумма действий отрицательно связана с гневом как чертой темперамента, иными словами, чем больше усилий мужчины-суициденты с ПТСР прилагали, чтобы покончить с собой, тем менее они обладают гневным темпераментом. Намеренность как сумма чувств и ожиданий (смерти, желания умереть и т.д.) оказалась обратно скоррелирована с чертой ТА4 Уступчивость и ТА2 Честность (обе из домена Сотрудничество). Таким образом, чем сильнее мужчины с ПТСР демонстрировали намеренность во время суицидальных действий, тем вероятнее они характеризовались стремлением подавлять свою агрессию, быть уступчивыми и честными по отношению к другим людям [54]. Данный паттерн свидетельствует о сложной и неоднозначной психологической природе мужчин-суицидентов с ПСТР, в которой подавленная агрессия играет, судя по всему, немалую роль. Из числа других аналогичных по силе ассоциаций у мужчин следует отметить прямую корреляцию намеренности в виде чувств с занятостью (числом рабочих месяцев в году) и обратную связь между Честностью и возрастом.

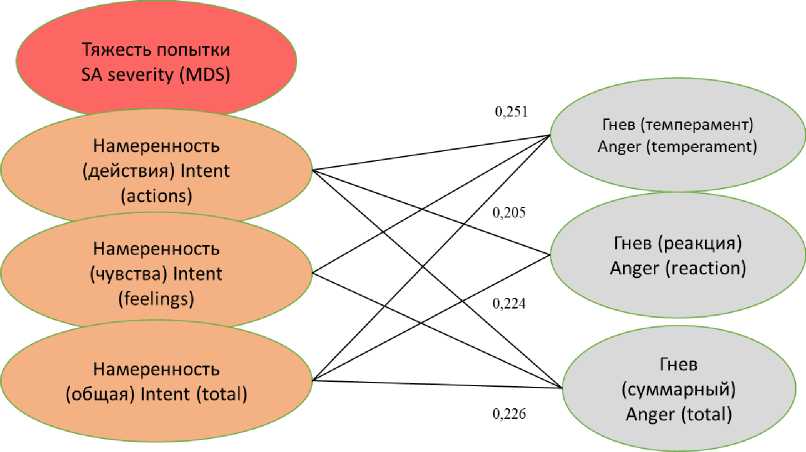

Иная картина наблюдалась среди женщин с ПТСР (рис. 3). Как видно из рисунка, тяжесть попытки у них не имела ни одной значимой ассоциации ни с личностными, ни с психосоциальными характеристиками.

According to the test interpretation, in its lowest manifestations this trait means extreme pertinacity, i.e., such people tend to be very competitive or aggressive [54]. People with this characteristic easily fall into anger, which in our case is well confirmed by significant inverse correlations of average strength with anger scores as a temperament trait and as a reaction to stimuli. Intentionality on the Beck scale, in particular, its behavioral component, was positively associated with the trait TO3 – Feelings. Persons with this sharpened characteristic experience both happiness and unhappiness more emotionally, often get overwhelmed with their emotions [54].

At the same time, intentionality as a sum of actions was negatively correlated with anger as a temperament trait, in other words, the more effort male suicide at-tempters with PTSD made to harm themselves, the less anger temperament they possess. Intentionality as the sum of feelings and expectations (death as outcome, wish to die, etc.) was inversely correlated with the trait TA4 Compliance and TA2 Honesty (both from the Agreeableness domain). Thus, the more men with PTSD demonstrated intent during suicidal acts, the more likely they were characterized by a desire to suppress their aggression and to be compliant and honest with others [54].

0,205

0,224

0,226

Гнев (темперамент) Anger (temperament)

Гнев (реакция) Anger (reaction)

Намеренность (чувства) Intent (feelings)

Намеренность (общая) Intent (total)

Намеренность (действия) Intent (actions)

Тяжесть попытки SA severity (MDS)

Гнев (суммарный) Anger (total)

Рис. 3. Наиболее выраженные по силе и значимые ( p <0,05) корреляционные связи тяжести и намеренности СП с переменными, характеризующими женщин-суицидентов с ПТСР / Fig. 3. The strongest and significant ( p <0,05) correlations of SA medical severity and intent with variables featuring female suicide attempters.

Все значимые корреляции, приближающиеся к связям средней силы (в пределах r =0,226-0,251) были между компонентами намеренности и проявлениями гнева (гнев как черта темперамента, как реакция, и суммарный показатель). Эти взаимосвязи были прямо пропорциональными, то есть намеренность у женщин с ПТСР прямо коррелировала с выраженностью гнева. Таким образом, женщины с ПТСР не демонстрировали черт и ассоциаций, которые бы свидетельствовали об агрессии, все их намерения свести счеты с жизнью в большей мере связаны с гневом, возможно, как реакцией на переживание тех травмирующих ситуаций, которые стали причиной их ПТСР.

Что касается корреляционных находок тяжести и намеренности в группе суицидентов без диагнозов, то их число было несколько больше, чем среди пациентов с ПТСР, однако все значимые связи были ещё слабее (в пределах r =0,100-0,150), что не позволяет говорить о существенных ассоциациях. В то же время, заслуживает внимания то, что и у женщин, и у мужчин из этой группы намеренность была значимо и прямо связана с уровнем депрессии по Беку ( r =0,150-0,200), чего вообще не наблюдалось среди пациентов с ПТСР.

Обсуждая полученные нами результаты в целом, нужно отметить, что нами впервые представлена подробная характеристика нефатального суицидального поведения при наличии диагноза ПТСР, причём дифференцированно среди мужчин

This pattern depicts a complex and ambiguous psychological nature of male suicidal individuals with PSTD, in which repressed aggression seems to play a significant role. Other strongest associations in men include a direct correlation of Intentionality (feelings) with employment (number of working months per year) and an inverse relationship between Honesty and age.

A different picture was observed among women with PTSD (Figure 3). As can be seen, the medical severity of the attempt had no significant association with either personality or psychosocial characteristics in them.

All significant correlations approaching medium strength (within the range of r =0.226-0.251) were between the components of intentionality and anger (as a trait, reaction, and total). These correlations were direct, i.e., intent in women with PTSD was directly correlated with expression of anger. Thus, women with PTSD did not show traits and associations that would involve aggression, their intentions to end their lives appear to be related to anger, perhaps as a reaction to experiencing the traumatic situations that caused their PTSD.

As for significant correlations between severity and intentionality with other variables in the group of suicide attempters without diagnoses, they were slightly more numerous than among patients with PTSD, but were even weaker (within the range of r =

и женщин, в сравнении с суицидентами без диагнозов. Наши данные интересно сопоставить с аналогичным китайским исследованием, в котором всех суицидентов с любыми психиатрическими диагнозами сопоставляли с суицидентами без явных психических расстройств [46]. В этой работе авторы, не дифференцируя между мужчинами и женщинами, обнаружили, что среди тех, кто имел какое-либо расстройство, выраженность суицидальной идеации и риск суицида был выше, у них также были выше баллы депрессии и нейротизма. В то же время, у тех, кто совершил попытку не имея расстройств, была выше импульсивность, и они чаще употребляли алкоголь, при этом лица с расстройствами чаще использовали «высоколетальные» способы, куда авторы причисляют отравления пестицидами, моноксидом углерода, прыжки с высоты и повешения, противопоставляя им «низколетальные» способы, куда вошли отравления барбитуратами, бензодиазепинами и самопорезы [46]. Авторы особо отмечают своеобразие того контингента в Китае, который совершает попытки, не выявляя никаких признаков психических расстройств, что подчеркивает значение этнокультурального фактора. Интересно, что культурные факторы при этом проявляются даже в понимании высокой и низкой потенциальной летальности способов само-повреждения, не совпадающей с трактовкой западных авторов [47].

Другое исследование, близкое к нашему и выполненное в США, приводит данные об особенностях суицидального поведения женщин с пограничным личностным расстройством (ПРЛ) при наличии ПТСР как дополнительного диагноза [56]. Женщины с ПРЛ и ПТСР отличались более высокой намеренностью и тяжестью совершенных попыток, более выраженными нарушениями эмоциональной регуляции и высокой коморбидностью c тревожно-депрессивными расстройствами и нарушениями пищевого поведения [56]. В другом исследовании сочетание ПТСР и депрессии у суици-дентов из Норвегии было сопряжено с большей выраженностью самоповреждающего поведения, но не влияло на намеренность суицидального акта [57]. Такие противоречивые данные говорят о значительной роли этно-культуральных особенностей обследованных контингентов, которые накладывают отпечаток на нефатальное суицидальное поведение при ПТСР. В целом следует согласиться с мнением, что ПСТР – исключительно сложное и

0.100-0.150), which does not allow us to speak of significant associations. At the same time, it is noteworthy that in both women and men in this group, intent was significantly and directly associated with Beck depression scores ( r =0.150-0.200), which was not observed at all among patients with PTSD.

Discussing our results in general, it should be noted that we have for the first time presented a detailed characterization of nonfatal suicidal behavior in the presence of a PTSD diagnosis, differentiated among men and women, compared to suicidal individuals without diagnoses. It is interesting to compare our results with a similar Chinese study in which all suicidal patients with any psychiatric diagnoses were compared with suicidal patients without overt psychiatric disorders [46]. In that study, the authors, without differentiating between men and women, found that those with any disorder had higher suicidal ideation and suicide risk, as well as higher depression and neuroticism scores. At the same time, those who attempted suicide having no disorder were more impulsive and more likely to use alcohol and exploited “high-lethal” methods, including pesticide poisoning, carbon monoxide poisoning, jumping from heights, and hanging, as opposed to “low-lethal” methods, including barbiturate poisoning, benzodiazepines, and self-cutting [46]. The authors emphasize the peculiarity of the contingent in China who attempt suicide without showing any signs of mental illness, which once more depicts the importance of the ethno-cultural factor. It is interesting that cultural factors are manifested even in the understanding of high and low potential lethality of self-harm methods that does not coincide with the interpretation of Western authors [47].

Another similar to ours study (conducted in the USA) provides data on the peculiarities of suicidal behavior in women with borderline personality disorder (BPD) in the presence of PTSD as an additional diagnosis [56]. Women with BPD and PTSD were characterized by higher intentionality and severity of attempts, more pronounced disturbances in emotional regulation, and higher comorbidity with anxiety, depressive disorders and eating disorders [56]. In another study, the combination of PTSD and depression in Norwegian suicide attempters was associated with greater severity of SA, but did not affect the inten-

неоднозначное расстройство, требующее детального анализа в каждой конкретной популяции или особой группе лиц, подверженной этой патологии. ПТСР как расстройство является источником значительных противоречий и разногласий, как при клинической трактовке, так и на уровне специальных исследований [58]. Ещё в большей степени это касается суицидального поведения при ПТСР, что подчёркивает необходимость дальнейших исследований в этом направлении.

Связь ПТСР с суицидальным поведением сильно зависит от черт личности, характера и темперамента, среди которых такие черты Большой Пятёрки как Экстраверсия / Интроверсия и Нейро-тизм, а также безнадежность как конструкт играют важнейшую роль [59-61]. Наши данные, которые уточняют роль этих личностных черт применительно к мужчинам и женщинам с суицидальным поведением и ПТСР, позволяют более дифференцированно подойти к таким пациентам при выстраивании психотерапевтических мероприятий. Судя по всему, при работе с суицидентами-мужчинами с ПТСР основное внимание должно быть уделено их агрессии, в то время как при работе с женщинами – их обидам и гневным реакциям. Важно то, что все эти результаты получены применительно к славянской ментальности, примерно отражают присущий нашей популяции уровень образования, соответствуют культурной ситуации тех контингентов, которые в настоящее время подвергаются повышенному риску развития посттравматических состояний.

Наше исследование имеет ряд ограничений. Основное из них связано с тем, что само исследование носит ретроспективный характер, поскольку все характеристики, как психиатрические, так и связанные с СП и личностными качествами, оцениваются в постсуицидальном периоде. Таким образом, мы не можем установить последовательность событий – факта СП, развития симптомов ПТСР, или личностных деформаций. Из самых общих соображений можно утверждать, что скорее всего черты личности в рамках модели Большой Пятерки (во всяком случае такие, как Экстраверсия, Нейро-тизм и Сотрудничество) частично генетически обусловлены и являются результатом ранней социализации. Соответственно, они, вероятнее всего, являются предрасполагающими факторами. Второе ограничение касается невозможности определить последовательность событий. Среди суицидентов в tionality of the suicidal act [57]. Such contradictory data suggest a significant role of ethno-cultural peculiarities of the surveyed contingents, which impact non-fatal suicidal behavior in PTSD patients. In general, one should agree with the opinion that PTSD is an extremely complex and ambiguous disorder that requires detailed analysis in each specific population or group of individuals exposed to this pathology. PTSD as a disorder is a source of considerable controversy and disagreement, both in clinical interpretation and at the level of specialized research [58]. This is even more true for suicidal behavior against the background of this disorder, which emphasizes the need for further research in this area.

The association of PTSD with suicidal behavior is strongly influenced by personality, character, and temperament traits, among which the Big Five traits of Extraver-sion/Introversion and Neuroticism, as well as hopelessness as a construct, play a crucial role [59-61]. Our data, which clarify the role of these personality traits in men and women with suicidal behavior and PTSD, allow for a more differentiated approach to these patients when building psychotherapeutic interventions. It may be suggested that while working with male suicidal patients with PTSD, the focus should be on latent aggression, while when working with women – on their resentment and angry reactions. It is important that all these results are obtained in relation to the Slavic mentality, approximately reflect the level of education inherent to our population, and corresponds the cultural situation of those contingents who are currently at increased risk of developing post-traumatic conditions.

Our study has a number of limitations. The main one is related to the fact that the study itself is retrospective, since all characteristics, both psychiatric, SA-related as well as personality traits, are assessed in the post-suicidal period. Thus, we cannot establish the sequence of events – the fact of SA, the development of PTSD symptoms, or personality deformations. From the most general considerations, it is likely that the Big Five personality traits (at least Extraversion, Neuroticism, and Agreeableness) are partly inheritable and are the result of early socialization. Accordingly, they are likely to be predisposing factors.

данной выборке время, прошедшее от момента СП до интервью, составляло от нескольких дней до месяца и более. В последнее время появились сообщения о возможности развития ПТСР вследствие СП, однако они не подкреплены достаточной эмпирической базой [62]. В то же время, неоднократно упоминалось, что СП может быть и фактором катарсиса [63], и причиной ухудшения психологического статуса [64]. Она может быть результатом психического расстройства, но может возникать и у психически здоровых индивидов [64]. Что касается, ПТСР, то это расстройство возникает (или диагностируется) в разных культурах с очень большими различиями, а его взаимосвязи с суицидальностью неоднозначны и противоречивы. Эти неопределённости не разрешены в данном исследовании, что указывает на возможные направления дальнейших изысканий.

Заключение

Проведённое исследование в основном подтвердило высказанные гипотезы. Нефатальное суицидальное поведение у лиц славянского происхождения с ПТСР отличается более высокой летальностью, намеренностью, сопряжено с более выраженной безнадёжностью и депрессивными симптомами. Эти отличия проявляются при сопоставлении с суицидентами без психиатрических расстройств, что делает эти наблюдения ценными для тех психиатров и медицинских психологов, которые консультируют и оказывают помощь лицам с СП, поступающим в стационары общего профиля в связи с самоповреждениями. Женщины (при том, что они скорее всего будут количественно преобладать среди этого контингента) более чувствительны к влиянию ПТСР как дополнительного фактора, проявляя ряд поведенческих черт, характерных для «мужского» типа суицидальных действий. Их основной психологической и эмоциональной проблемой является гнев, они более подвержены влиянию безнадёжности как проявлению пессимизма в отношении будущего.

Мужчины-суициденты с ПТСР мало меняют своё суицидальное поведение по сравнению с суи-цидентами без психиатрических расстройств. Их основной психологической и эмоциональной проблемой является скрываемая агрессия, они неуступчивы и остро переживают позитивные и негативные чувства. Их гнев скорее всего обусловлен последствиями подавления агрессивных импульсов. Для данного контингента, как мужчин, так и женщин, коморбидная депрессия (которой придаёт-