The diffusion of volunteering abroad and in Russia: cultural foundations, assessment of barriers, intensification technologies

Автор: Bazueva Elena V., Artamonova Anna S.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social and economic development

Статья в выпуске: 6 т.14, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The need to integrate volunteering into national strategies for achieving sustainable development goals, and the importance of its role in curbing the implications of crisis processes caused by the coronavirus pandemic have intensified the scientific search for barriers to civic participation in volunteering and mechanisms for eliminating them. At the same time, researchers focus on identifying barriers of a certain type on the example of one country or group of countries, and, when searching for ways to eliminate those barriers, they underestimate the role of national culture. The purpose of our study is to systematize barriers and promising technologies for intensifying the diffusion of volunteering among the population and to identify major features of national culture in this process. Barriers to the diffusion of volunteer activity in society are systematized into three groups: barriers on the part of the state, barriers on the part of the non-profit sector, and barriers on the part of the individual. We show national features of their formation, which proceed from the specifics of emergence and evolution of volunteerism in the course of socioeconomic development. Using the postulates of institutional economic theory, we identify a system of institutions that intensify the diffusion of volunteering in society, including institutions for the promotion of volunteer practices, institutions for the development of civil society, institutions for the development of horizontal ties through network mechanisms for the diffusion of norms of civic participation, institutions for improving the reputation of volunteering among the population, the institute of volunteer education, institutions for increasing the motivation of participation in volunteering. On the basis of econometric analysis, we have determined that the cultural dimensions highlighted by G. Hofstede, such as the level of individualism, femininity and tolerance, have a significant impact on the extent of development of volunteering in the country. Taking into account the identified cultural features and effective technologies that promote residents’ engagement in volunteer activities, we determine directions for intensification of this process in Russia. Development of a comprehensive system of institutions for the diffusion of volunteering in our country will be a promising area for our future research.

Development of volunteering, barriers, leveling mechanisms, formal and informal institutions, institutions that intensify the diffusion of volunteering, national culture, hofstede's cultural dimensions, sustainable development

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147236301

IDR: 147236301 | УДК: 316.45 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2021.6.78.14

Текст научной статьи The diffusion of volunteering abroad and in Russia: cultural foundations, assessment of barriers, intensification technologies

Currently, the world community, researchers, and civil society representatives become more and more concerned about issues related to the algorithm for achieving the goals of sustainable development, which requires a uniformity of the results of development of national socio-economic systems in economic, social and environmental directions. In this context, attention is focused on identifying the drivers of sustainable development that help to achieve the established target indicators. One such driver, according to the UN, is the extent of integration of volunteering into national strategies for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda1. It is for this reason that the governments, when preparing voluntary national reviews of progress towards sustainable development for the period up to 2030, turn to various forms of civil society participation, including volunteerism2; besides, the implementation of various UN projects with the participation of volunteers across countries worldwide is highlighted in the aspect of achieving specific sustainable development goals3.

Awareness of volunteers’ considerable contribution to sustainable development is due to their proximity to the targeted solution of various problems of local communities through interaction with major stakeholders – private sector, authorities and population. In this case, citizens become aware of their involvement, interest and personal responsibility in addressing local issues integrated with the achievement of global trends in the sustainable development of society4.

In addition, the need to attract volunteers in order to reduce social risks and stabilize destructive social processes became especially acute in 2019 due to the spread of COVID-19 infection [1]. The crisis processes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have led to a rapid increase in the number of volunteers. For example, in the UK, within 24 hours of a governmental call for citizens to join the National Health Service volunteers, 500,000 people signed up5. In Russia, the number of volunteers, according to the portal Добро.ru6, from 2019 to 2020 increased by almost 70 thousand people. In order to support volunteers who took care of citizens in need of help and care in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government of the Russian Federation adopted the regulations for special payments for volunteering during the crisis7. So, for example, Medical Volunteers – the all-Russian public movement of volunteers in the healthcare sector – in 2020 was allocated more than 242 million rubles from the reserve fund of the RF Government8.

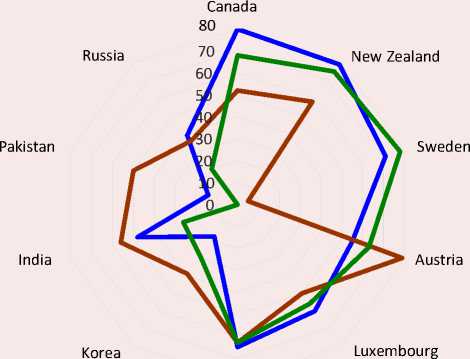

Despite the acknowledgment of the contribution of volunteerism to the development of national socio-economic systems and solution of socially significant issues, the level of its dissemination worldwide remains low. Thus, according to the 2018 State of the World’s Volunteerism Report. The Thread That Binds, the share of volunteers in the total population did not exceed 7% in 20169. The top five countries according to this indicator were Canada (6.98%), New Zealand (6.46%),

Luxembourg (6.28%), Sweden (6.14%), Austria (5.99%). Such countries as Pakistan (0.39%), India (0.69%), Korea (0.73%), South Africa (0.85%), and the Russian Federation (0.98%) were outsiders in terms of civic participation in volunteerism10.

The above has determined a necessity to intensify scientific search for barriers to civic participation in volunteering and mechanisms for their elimination. At the same time, judging by the results of our analysis, researchers, as a rule, focus on identifying barriers of a certain type on the example of one country or group of countries. Thus, researchers consider the involvement of the elderly [2; 3; 4] and youth [5; 6] in public life in the form of volunteering; they analyze gender differences in civic participation [7; 8], investigate the development of volunteerism in the field of environmental protection [9], sports [10], etc. The most comprehensive works include, for example, reports on the situation regarding volunteerism in the European Union member states11.

The reduction of barriers is considered from the point of view of managing individual preferences in terms of increasing readiness (individual motivation and values), enhancing the opportunities provided and the expected availability of participation in volunteering [4; 11; 12], as well as measures taken by the government to promote public participation in volunteerism12 [5]. However, only few studies emphasize the formation of culture and promotion of the value of volunteerism in society. In this aspect, volunteering is perceived as a pledge of prosocial behavior, as a factor contributing to the improvement of social justice and social responsibility [13].

It is worth mentioning that we have not come across articles that would propose to differentiate the establishment of such conditions taking into account cultural specifics of the country, which predetermine the choice and consolidate the relevant norms of behavior in “collective action”. In this case, we are talking about informal institutions with deep historical roots, transmitted through training and imitation from one generation to another, which, as a rule, are internally binding standards of behavior for an individual [14, p. 57]. These rules of social interaction determine the hierarchy of values shared by broad strata of society, people’s attitude toward power, mass psychological attitudes, attitudes toward cooperation and confrontation, etc. [15]. Recently, researchers have been paying increasing attention to the importance of the influence of these cultural values and attitudes on the effectiveness and individual parameters of development of national socio-economic systems [16; 17].

Institutional studies emphasize that the cultural attitudes, unlike formal institutions, are changing slowly. “Theorists believe that informal institutions can be stable for up to 1,000 years. But with targeted impact, significant progress can be achieved in 25 years, and the almost complete change – in 40 years”13. In this case, it is possible to introduce formal institutions that contradict informal rules; as a result, economic entities may develop resistance to their implementation or manifest various forms of opportunistic behavior. With regard to volunteerism, this means that its intensification imposed by the government will not be effective if the values of volunteerism do not fit into the cultural framework of the country.

We should note that at present some studies focus on the differences in the value of volunteerism depending on the cultural attitudes of population in various countries. Thus, P. Lukka and A. Ellis emphasize that the understanding of volunteering will be determined by differences in the people’s social, cultural, historical and political environment [18].

H. Gronlund et al., using the example of crossnational comparisons of 13 countries, proved that the value of volunteering, motives and intensity of participation of bachelor degree students in volunteering have statistically significant differences depending on the country of residence of the students, i.e. they are determined by national culture in general and by the support for the nonprofit sector in particular [19].

Developing the results of previous studies, A. Aydinli, M. Bender, A. Chasiotis show that there is a relationship between the diversity of national culture in terms of its individual and collectivist components, which, according to the authors, determine the level of national wealth, trust in strangers, and the prevalence of volunteering as a formal type of assistance to the population. In developed countries where individualism is widespread, people are more often involved in volunteering [20]. However, in the present paper, we do not focus on identifying the relationship between other cultural features and the level of development of volunteerism.

Based on the above, the purpose of our research is to systematize barriers and promising technologies in promoting the diffusion of volunteerism among the population and to identify significant features of national culture in this process.

Let us start by identifying the barriers that hinder the development of volunteering and analyzing effective foreign technologies to eliminate them.

Barriers to the development of volunteerism and mechanisms of their elimination: Russian and foreign experience

According to the analysis of scientific literature, we reveal a wide range of barriers that hinder the active development of volunteerism. The barriers can be arranged into three groups: barriers on the part of the state, barriers on the part of the non-profit sector and barriers on the part of the individual (Tab. 1) .

We should emphasize that such a division is conditional, since involvement in volunteerism is determined by a system of interrelated factors that one may be only partially aware of. Barriers are often specific, depending on the scope of implementation of volunteer projects. For example, physical characteristics are of great importance for volunteer practices in the field of sports. In addition, barriers to the diffusion of volunteerism have national features, due to the specifics of emergence and evolution of this phenomenon in the process of socio-economic development of the country, and modern factors determining the trajectory of this phenomenon.

Thus, in the countries in which the share of volunteers in the total population is the greatest, the development of volunteerism was largely determined by strong religious traditions that support the manifestation of altruism, social solidarity and mutual assistance. For example, in Canada, under the influence of the church, institutions were formed to support the poor, the sick, and the disabled (hospitals, homes for the poor and disadvantaged). Volunteering was perceived as an act of goodwill, an indicator of kindness and compassion. Further processes of development

Table 1. Classification of barriers to the diffusion of volunteering in society

Barrier Manifestation On the part of the state Institutional barriers Weak institutional support for the non-profit sector as a whole and the lack of mechanisms for involving the population in associate participation (Romania [5], USA [21], Scotland [9], Russia [22]), excessive bureaucratization of volunteering (Germany*). On the part of the third sector Information asymmetry Uneven dissemination of information about the opportunities, conditions and results of participation in volunteering (UK [23, p. 18], Slovenia, Lithuania, Poland [10], USA [24]). High organizational risks Flaws on the part of NGO management in organizing events in the system of involvement and retention of volunteers (USA [4; 25], Slovenia, Lithuania, Poland [10], UK [26]). Low level of diffusion of volunteering in the environment Low level of public trust in volunteer practices, high dependence of the level of involvement in volunteering on the channel of information dissemination (invitation by acquaintances). Devaluation of volunteering as a frivolous and insignificant occupation. The barrier is especially pronounced for young people (Spain [27], USA [28], the Netherlands [29], Israel [30], Russia [31]). Financial risks High probability of non-fulfillment of obligations in full within the framework of the activities due to restrictions on the financing of individual expenses of volunteers for transport, accommodation, food (USA [25], Slovenia, Lithuania, Poland [10], Ghana [32]). On the part of the individual Limited time resources Limited involvement in volunteering in connection with employment at the main job, studies, family responsibilities and child care. It is especially relevant among women (UK [23], USA [8; 33; 34], Germany [7], Scotland [9], Australia**, Slovenia, Lithuania, Poland [10]). Individual project conditions Conditions of volunteer projects limit participation for certain groups. For minors – due to legal restrictions, for the elderly, difficulties are associated with health problems, for people with disabilities – due to the biased attitude of others who perceive them only as recipients of assistance or as an additional organizational burden (USA [3; 4; 6; 35; 36], New Zealand [37], Slovenia, Lithuania, Poland [10], UK [23], Ireland [38]). Low motivation to participate in volunteering The substitution effect in the distribution of free time, when preference is given to other interests not related to volunteering (Mexico [39], USA [6], Romania [5], Australia **). * National report – Germany. Study on Volunteering in the European Union. 54 p. ** Source: own compilation.

of the socio-economic system (industrialization, urbanization) and external shocks (the Great Depression, world wars) necessitated the emergence of volunteer associations to help socially vulnerable population groups and led to the intensive development of new forms of civic engagement. Despite the active participation of the state in the creation of institutes of healthcare, education, urban planning, etc., volunteering since the 1960s becomes a sign of a strong democratic society, where a whole range of diverse organizations is developing at the local, regional and national levels [2, pp. 153–156].

Religious traditions have had a noticeable impact on the development of volunteerism in European countries, which are also leading in terms of civic participation in volunteer activities [40, p. 69]. In addition, as H.K. Anheier and L.M. Salamon emphasize, the national features in the development of the third sector and volunteerism were largely determined by the specifics of industrialization of socio-economic systems in terms of redistribution of power [41]. In particular, in those countries where, during the period of industrialization, industrialists were able to adjust national policy to suit their economic interests, a “liberal model” of civil society development was formed, which is characterized by a large number of NGOs receiving major funding from private sources (subscriptions, charitable contributions). Such a model became widely used in the UK and Switzerland. In countries where industrialization has led to an increase in the working class and the number of NGOs representing its interests, a model of “welfare partnership” has emerged, which is characterized by significant state participation in financing the social sphere through volunteer organizations, most often religious ones. The model is most pronounced in the states of Northwestern Europe, especially in Germany and the Netherlands. In countries where growth was observed in relation to the working class and farmers, a social democratic model has emerged in which social services are viewed as a “right”

of all citizens rather than a gift from charitable organizations. Services are provided directly by government agencies. In Europe, this model is typical of the Scandinavian countries and Austria, which are leaders in the diffusion of volunteering among the population. In countries where the state plays a dominant role and seeks to carry out rapid modernization with the restriction of personal freedom of citizens, the development of civil society is shifting to the sphere of the informal economy. According to researchers, this “static” model is typical of Russia, Turkey, Spain, Portugal and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe [40, pp. 70–73].

We can highlight active migration processes as modern factors determining the intensity of diffusion of volunteerism. They largely determine the specifics of volunteering in the host countries and also act as a deterrent to the civil participation of migrants. For example, in Canada, Sweden, Austria, New Zealand and Luxembourg, a network of non-profit organizations, whose activities are more supported by local population, has been created in order to engage migrants more effectively. On the contrary, outsider countries in terms of the share of volunteers in the total population (South Africa, Korea, India, Pakistan) are characterized by opposition to the rules established by international organizations [42, pp. 37–39], a negative attitude toward migrants, largely due to the historical past – colonization, racial and ethnic segregation, missionary activities to spread Christianity. In addition, traditional values act as a deterrent; they in many ways contradict the development priorities determined by international organizations that provide grants to volunteer projects [42, p. 93; 43, p. 10]. In general, the third sector in these countries is less institutionalized and is heavily dependent on state power. For example, as Korean scientists note, due to the fact that civic activity is often sanctioned by the state, the attitude of the population toward associated participation is mostly negative [44].

Russia belongs to the countries with the smallest share of volunteers in the total population. Russia’s practices of involvement in volunteerism were also determined by the change of cultural and value attitudes in the process of development of society and the transformation of socio-economic systems. Mutual assistance and mutual support typical of Russian culture have made the peasant community one of the most stable institutions [45, p. 16]. In the 19th century, there emerged a form of civic participation such as providing assistance to the needy (for example, “going to the people” by representatives of the intelligentsia, or city guardianship of the poor). During the Soviet period, the culture of volunteering was actively shaped by the state, which “included” an individual in socially useful and socially significant activities. I.A. Kuptsova emphasizes that the formation of such a culture was supported by Soviet cinema and artistic works (a system of informal institutions14), demonstrating the huge potential of volunteerism and significant, often somewhat unrealistic, results [46; 47, p. 23]. In the early 1990s, people’s engagement in volunteering decreased significantly due to a sharp drop in living standards15 and a radical change in values, when Soviet principles began to contradict the system of formal institutions that were being introduced at the time [48; 49], and imported approaches to the development of the third sector did not provide a significant restructuring of the system [47, p. 32]. At the same time, in the framework of our research, it is important to emphasize that “many of the former values have not disappeared, but receded into the background and now remain in a latent state” and “can be actualized in a modified way” [50, p. 114] if there is a demand for them in the system of formal institutions. In general, we should note that the current system of state support for volunteering in Russia remains ineffective at all levels of government, and the dominant positions of the state correlate with limited opportunities for the development of the third sector [22, p. 78; 32].

Given the diversity of the identified barriers to the diffusion of volunteerism, it seems obvious that the ways to overcome them should be purposeful and focused on solving specific problems. According to the analysis of foreign studies we systematize the main directions for eliminating the barriers according to various types of institutions that consolidate the norms of volunteer practices, create conditions for their effective development in society, and also contribute to changing the mental structures of individuals through a system of motivations for participation in volunteering (Tab. 2) .

Table 2. The system of specialized institutions to intensify the diffusion of volunteerism in society

|

Institution* |

Types of specialized institutions |

Countries |

|

Institutions for the promotion of volunteer practices |

Building cooperation between authorities, civil society and commercial structures Special departments for the development of volunteering among women Special laws and programs to encourage youth participation in volunteering, especially in rural areas National programs for the uniform distribution of volunteerism in the regions of the country Building cooperation with international alliances working in related fields in order to increase the importance of the opinion of local volunteers among national and regional authorities |

New Zealand, Luxembourg, Canada, Sweden, Austria, Australia, Peru Nepal, India, Bangladesh, Peru, Estonia Honduras, Mozambique, Togo, Ghana, Kenya China, UK Chile |

14 Clarification added.

15 See more in: Bodrenkova G. National IAVE representative for Russia and chairperson of the Moscow Charity House. Volunteer Center and advisor on the committee of Public and Religious affairs in the State Duma.

End of Table 2

Institution* Types of specialized institutions Countries Institution for the development of civil society (feedback system) Involvement of the population in legislative activity Canada, Sweden, Estonia, Iceland, Austria, Luxembourg Institution for the development of horizontal ties through network mechanisms of diffusion of civic participation norms Creating and expanding special platforms for joint discussion of community issues (“invited spaces”) Nepal, Kenya, Uganda, Brazil, Peru, New Zealand, Austria Institutions for improving the reputation of volunteer activity among the population Establishment of a year of volunteer activity for 17–28-year-old people, during which they work in one of the country’s social organizations full-time, receiving a small monthly allowance Giving awards to volunteer organizations; promoting scientific and educational institutions to conduct research on the topic of civic participation Austria Nepal, Kenya, Uganda, Brazil, Peru, New Zealand, Austria Institution for volunteer training Organizing forums to increase women’s participation in volunteering through the development of relevant knowledge and skills Nepal, India, Peru, Bangladesh Institutions for increasing motivation to participate in volunteering Creation of a “volunteer passport”, which contains information about all volunteer practices in which an individual participated, with a list of skills used in this process Exemption of expenses related to volunteer activities from individual income tax, preservation of unemployment benefits when concluding a contract for volunteering Austria, France, Australia Macedonia * Own elaboration based on the provisions of the institutional economic theory. Compiled according to: Laws and Policies Affecting Volunteerism Since 2001. A Research Report. United Nations Volunteers (UNV), 2009. 103 p.; State of the World’s Volunteerism Report. Transforming Governance. United Nations Volunteers (UNV), 2015. 132 p.; Study on Volunteering in the European Union. National Report – Austria. 28 p. Available at: ; ; ; ; ; [51; 52; 53].

The data in Table 2 show that the most developed network of specialized institutions aimed at intensifying the diffusion of volunteerism in society is typical of the countries in which the engagement of the population in this form of civic participation is most widespread. We emphasize that in such countries these institutions stabilize the consolidation of volunteer practices in the system of direct, reverse and horizontal links, which forms a favorable environment for a self-sustaining institutional system [54].

In general, as our analysis has shown, technologies for eliminating the barriers to the development of volunteerism are not integrated into the cultural structure of the country. A vivid example is the attempts to involve women in the discussion and solution of social issues in patriarchal societies, among other things, in the form of volunteering, which contradicts the current system of informal institutions. We think that if cultural features that intensify the development of volunteerism are taken into account, it would improve the effectiveness of the proposed mechanisms, since it would be consistent with the values of the majority of the country’s population. The next section of the article is devoted to the identification of these cultural features.

Econometric analysis of the relationship between the intensity of the diffusion of volunteerism and the cultural parameters of the country

According to our hypothesis, national culture should have certain values and behavioral attitudes that promote the dissemination of volunteerism among the population.

The proportion of volunteers in the total population is an effective feature in the model. We believe that in comparison with the absolute value of this indicator in the form of the number of volunteers in the country, it allows us to take into account the extent of the spread of volunteerism in society. We should note that currently only the absolute indicator is presented in government reports on the state of volunteering, so we calculated its relative value on our own16.

The explanatory variables are the cultural dimensions highlighted by G. Hofstede, the designations of which are presented in Table 3. The variables are measured in points from 1 to 100. Secondary empirical data of the HOFSTEDE INSIGHTS17 project were used, the methodology of which for all six indicators is described in detail in [16]. We emphasize that, despite the different period of data used to build the model, they are comparable, because, as we noted earlier, the characteristics of national culture change very slowly over time.

The analysis was carried out on with the use of the data for 55 countries for which all indicators were available; therefore, the sample is balanced. The calculations were carried out using Gretl software package. The constructed linear regression model (the value of the coefficient of determination R2 = 0.46) revealed that 46% of all factors affecting the level of volunteerism in society can be explained by the specifics of national culture, since, as we showed in the previous section, the range of factors is quite diverse. In addition, we have found that such factor variables as “Power Distance”, “Uncertainty Avoidance”, and “Long Term Orientation” do not have any significant influence on the level of volunteering in the country.

In our opinion, the absence of a significant correlation with the Long Term Orientation dimension is due to the fact that most of the

Table 3. Cultural dimensions of Hofstede’s theory

|

Dimension |

Designation |

Description |

|

Power Distance |

PD |

Shows the extent to which members of a society or organization endowed with relatively less power expect and allow an uneven distribution of power |

|

Individualism |

Ind |

The extent to which people in society are integrated into groups; assumes that everyone will take care of themselves and their closest relatives; on the contrary, collectivism is aimed at integrating people from birth into strong, cohesive groups, often large families (with uncles, aunts, grandparents), which are designed to protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty |

|

Masculinity |

M |

The degree of prevalence of masculine social values in society, accompanied by high competition, differentiation of gender roles in society, orientation toward achievement and success |

|

Uncertainty Avoidance |

UA |

Shows the extent to which people belonging to the same culture will be afraid of uncertain and unfamiliar situations |

|

Long Term Orientation |

LTO |

Shows the extent of pragmatism and strategic orientation for the future, in particular perseverance, thrift, in society |

|

Indulgence |

I |

Shows the extent to which people in society control their desires in satisfying natural and social needs, including those related to the organization of leisure |

|

Compiled according to: Auzan A.A., Nikishina E.N . Sotsiokul’turnaya ekonomika: kak kul’tura vliyaet na ekonomiku, a ekonomika – na kul’turu: kurs lektsii [Socio-Cultural Economics: How Culture Affects the Economy, and the Economy Affects Culture: A Course of Lectures]. Moscow: Ekonomicheskii fakul’tet MGU imeni M.V. Lomonosova, 2021. Pp. 39–45; [16]. |

||

16 We calculated the share of volunteers in the total population of the country on the basis of the 2018 State of the World’s Volunteerism Report. The Thread That Binds. Available at: and the Report on Volunteering in the Russian Federation. Available at: Public/NewsPage/

17

volunteer projects are implemented at the expense of budgetary funds and funds of international assistance in addressing current socially significant issues, the range of which is quite differentiated depending on the level of the country’s development. In addition, the funding of volunteer projects by international organizations erases a clear dependence of unresolved socio-economic problems on the national specifics, since sponsoring organizations set the vector of their implementation based on their own ideas and interests [18]. In general, we should note that these projects differ significantly from common investment projects; in our opinion, the difference is expressed in the absence of a significant relationship with the parameters of the time perspective, as well as the uncertainty of the external environment.

The absence of a significant causal relationship between the level of volunteerism and power distance is explained by the specifics of citizens’ involvement in volunteering (the initiative can either come from citizens or from the government).

The results of econometric modeling by stepwise regression are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Characteristics of econometric model parameters

|

Indicator |

Coefficient |

Standard error |

|

Const |

1.832*** |

0.6629 |

|

Ind |

0.034*** |

0.0084 |

|

M |

-0.022** |

0.0087 |

|

I |

0.026*** |

0.0089 |

|

Schwartz Criterion |

199.335 |

|

|

Coefficient of determination |

0.417 |

|

|

***, ** – significance at the 1 and 5% level, respectively. |

||

The established factor dependencies confirm our hypothesis, which consists in the fact that only certain values and behavioral attitudes in the national culture affect individuals’ preferences concerning the decision-making process about participation in volunteering. Moreover, the significance of their impact on this process, according to the data in Table 4, also differs. The Figure confirms the dependencies established by the model for the leading countries and outsider

Distribution of countries by type of culture in G. Hofstede’s theory

South Africa

^^^^^™ individualism ^^^^^™ masculinity ' I indulgence

Compiled with the use of: countries by the share of volunteers in the total population. In addition, the significance of the impact of cultural features on the level of volunteerism development is confirmed by the results of studies within individual countries.

First, according to the cultural dimensions highlighted by G. Hofstede, a high level of individualism implies personal responsibility for the achieved standard of living, the desire for selfrealization, as well as taking care, first of all, of oneself and loved ones. The emphasis on individual responsibility, active citizenship, and an individual approach to each person create conditions for caring for other members of society in the form of volunteerism. Such value attitudes, as I.A. Kuptsova emphasizes, motivate the involvement of middleaged people in volunteering [46].

The possibility to increase human capital by obtaining work experience and vocational training, developing new skills, establishing contacts useful for paid work and improving employment prospects is more typical for involving students in volunteer activities [12; 19; 46]. At the same time, according to the results of the study by H. Gronlund et al., these motives can be considered as the initial motive for involving students in volunteering or occasional participation in it [19]. The demand for volunteerism in this case is motivated by the greater loyalty of potential employers to candidates, since they assume that such employees in their professional activities will abandon personal interests in favor of the interests of the organization [19]. It is no coincidence that a high level of empathy is included in the group of so-called soft skills18, the priority of which in comparison with the accumulation of professional knowledge and skills (hard skills) is a modern trend of changing employers’ requirements to the quality of employees’ human capital [55; 56, p. 470]. According to the results of some studies, in countries where utilitarian motives for participating in volunteer activities are the generally accepted norm, volunteering increases the wages of employees from 6% (Canada) to 18% (Austria) [19]. We should note that these countries are among the top five in terms of the share of volunteers in the total population. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that utilitarian motives are more typical of occasional volunteering, whereas regular participation in volunteering is mainly determined by value (altruistic) motives [19].

Second, the inverse relationship with the cultural dimension “masculinity” means that the development of volunteerism is more widespread in national cultures of the feminine type, which are characterized by “sympathy for the weak”, as G. Hofstede puts it [16]. The values of caring correspond to the figurative constructions of ideas about volunteer activity that dominate in modern society and are among its essential features. We should note that the rootedness of such an idea of volunteering is ensured by the transfer of the experience of helping the needy and poor representatives of the middle class, widespread in the 19th century (see details in [18; 46]). However, at the present stage of society development, according to P. Lukka and A.E. Paine, the idea of volunteering only from the standpoint of helping those in need hampers the engagement of young people in volunteer activities and needs rebranding [18].

Third, the established significant dependence on the level of indulgence, which assumes relatively free satisfaction of basic needs connected with the enjoyment of life and active leisure, on the one hand, confirms that volunteering on the initiative of citizens, as we noted earlier, cannot develop in conditions of consumer survival standards, when people need to focus on solving their own problems. On the other hand, according to the research results, volunteering is considered by many as an active form of leisure organization, which is consistent with the above-mentioned content of this cultural dimension according to G. Hofstede.

We emphasize that freedom of speech and a selfsupporting order that does not involve a high concentration of law-enforcement structures is important in societies with a high level of indulgence. These factors act as necessary conditions for the formation of a civil society in which the involvement of people in volunteering is a generally accepted social practice [57].

In the next section we will outline the mechanism for eliminating the barriers that hinder the development of volunteering in Russia. We will proceed from the identified cultural features that contribute to the involvement of the population in volunteering, and the effective technologies we have analyzed.

Ways to intensify the diffusion of volunteering in Russia: Cultural grounds

According to the method of G. Hofstede, Russia is more characterized by the manifestation of collectivist culture (the value of the “Individualism” dimension is 39), feminine traits compared with masculine traits (the value of the “Masculinity” dimension is 36), as well as a high degree of limitation by social norms in the manifestation of one’s own needs, including those related to the organization of leisure, a tendency toward pessimism and cynicism (the value of the “Indulgence” dimension is 20)19. As for the first two cultural dimensions, the introduction of the principles of market economy into the institutional matrix (in the terms of S.G. Kirdina [58]) in the early 1990s led to a gradual change in their trajectory. This means that when determining the main directions for intensifying the diffusion of volunteerism in Russia, taking into account its cultural parameters, it is possible to use a synthesis of individual-collectivist measures, and also, along with the principles of the care economy20, focus on the formation of institutions to increase motivation for participation in volunteering.

First, the state can influence the level of development of volunteerism to a greater extent only through formalized structures (NGOs). Consequently, the main directions to intensify the spread of volunteerism among the population can be identified as an increase in the number of organizations, an expansion of the range of their activities that take into account the specific interests of potential volunteers (customization of volunteer practices), as well as increasing the availability of volunteer practices [59, p. 579]. It seems that for this purpose it is necessary to support the activities of non-profit organizations working with different target audiences so that participants feel belonging to a certain group. This will allow, on the one hand, to involve in public life that part of the population that has sufficient potential for civic participation in the form of volunteer activity, but needs to create special conditions (older people “yearning” for mass socially significant events of the Soviet type, young people seeking to build a network of social ties that can then be used to increase their human capital, etc.). On the other hand, this corresponds to the principles of collectivist culture, when representatives of the group seek to protect each other by providing assistance in various forms. In this case, greater coverage of various social groups is possible with the provision of assistance based on a more individualized approach to the needs of this group. At the same time, one should bear in mind that the effectiveness of involving the population in volunteering depends on the consistency of its organization. According to the experience of other countries, it is possible to solve this problem if there is a staff of key employees [60, p. 884]. In fact, they are a link between an individual and society; the strength and duration of each person’s interest in volunteering depends on their skills and abilities. Relying on the social connections of potential volunteers, the staff of NGOs, taking into account individual motives for involvement, providing effective communication, among other things via online platforms, and providing support in adapting to participation in volunteer practices, ensure the permanent expansion of the network of volunteers [61, p. 7]. Buddy system can become a promising technology for working with a potential volunteer; the system is an analogue of the partner program, when a friend is “assigned” to a person and the couple works together until a certain result is achieved21 [62, p. 257]. Based on the fact that at present in Russia the state is one of the key grantgivers of the third sector, it is necessary to pay more attention to the issues of financial support to NGOs in terms of increasing civic participation in addressing socially significant issues.

Second, gradual transformation of cultural values in Russia toward individualization and masculinity leads to an increase in orientation toward individual success, activity, ambition, and planning for the future [50, p. 128], which implies the mandatory formation of institutions to increase motivation for participation in volunteering. In this regard, through longitudinal studies, it is necessary to identify a range of factors that motivate civic participation in the form of volunteerism and, on this basis, develop a strategy for the development of volunteering in Russia, taking into account the identified individual needs, as well as provide access to volunteer practices to all population groups (including disabled people, migrants, etc.)22.

Third, in order to level out the manifestations of pessimism and cynicism among the population in relation to volunteers in Russia, it is necessary to form a system of institutions for improving the reputation of volunteering among the population in various forms (see Tab. 2). In addition, a strategy for rebranding volunteering should be developed, including a range of specialized activities for employers to raise their interest through awareness of the importance of attracting employees with experience in volunteering for the company. Of course, we should emphasize that the intensification of citizens’ involvement in volunteering is possible, as we noted earlier, only against the background of an increase in the standard of living and quality of life in Russia with a wide range of leisure opportunities and the promotion of its forms.

In general, we should point out that the mechanism for overcoming barriers that hinder the development of volunteerism in Russia should be based on the principles of its conscious promotion23 [64] through the creation of a comprehensive system of institutions (see Tab. 2), defining the conditions for the effective mobilization of volunteers on a systematic basis and supporting people’s motivation to participate in volunteer practices. In this section, we have identified only some of the possible directions that are consistent with Russia’s cultural structure, since the development of a comprehensive system of institutions for the diffusion of volunteerism in society is an independent study and is not among the tasks we set in the present article.

Conclusion

Setting goals for the sustainable development of national socio-economic systems involves the search for new resources to achieve them. One of the potential factors is the strengthening of the role of civil society in this process; this can be done through the integration of volunteerism into national strategies for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda. As the analysis has shown, despite the recognition of the contribution of volunteerism to solving socially significant problems, the level of its worldwide diffusion remains low. Having systematized barriers to the development and technologies for intensifying the diffusion of volunteerism abroad and in Russia, we find out that taking into account cultural values and attitudes of national socio-economic systems is the necessary condition for building the most effective mechanism for increasing the level of civic participation. The conducted research shows the importance of certain characteristics of national cultures in the process of involving the population in volunteering and, in relation to the Russian context, allows us to determine possible directions for its intensification, consistent with the cultural structure of the country. The results obtained are valuable both from a theoretical and practical point of view and can be further elaborated in the development of a comprehensive system of institutions for the diffusion of volunteerism in society.

Список литературы The diffusion of volunteering abroad and in Russia: cultural foundations, assessment of barriers, intensification technologies

- Artamonova A.S. Volunteering in the conditions of a pandemic: main trends. In: Global'nye vyzovy i regional'noe razvitie v zerkale sotsiologicheskikh izmerenii: mat-ly VI mezhdunar. nauch.-prakt. internet-konf. (g. Vologda, 29 marta – 2 aprelya 2021 g.): v 2-kh chastyakh. Ch. 2 [Global Challenges and Regional Development in the Mirror of Sociological Dimensions: Proceedings of the 6th International Research-to-Practice Online Conference (Vologda, March 29 – April 2, 2021): in 2 Parts. Part 2]. Vologda: FGBUN VolNTs RAN, 2021. Pp. 171–175 (in Russian).

- Arai S.M. Volunteering in the Canadian Context: Identity, Civic Participation and the Politics of Participation in Serious Leisure. In: Volunteering as leisure/leisure as volunteering. An International Assessment. Ed. by R.A. Stebbins, M. Graham. 270 p.

- McNamara T.K., Gonzales E. Volunteer transitions among older adults: The role of human, social, and cultural capital in later life. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 2011, no. 66B, pp. 490–501.

- Tang F., Morrow-Howell N., Hong S. Inclusion of diverse older population in volunteering. Nonprofit & Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 2009, no. 38, pp. 810–827.

- Pantea M.-C. Understanding non-participation: perceived barriers in cross-border volunteering among Romanian youth. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 2015, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 271–283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2013.793205

- Roker D., Player K., Coleman J. Challenging the image: The involvement of young people with disabilities in volunteering and campaigning. Disability & Society, 1998, no. 13, pp. 725–741.

- Helms S., McKenzie T. Gender differences in formal and informal volunteering in Germany. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary & Nonprofit Organizations, 2014, no. 25, pp. 887–904.

- Taniguchi H. Men’s and women’s volunteering: Gender differences in the effects of employment and family characteristics. Nonprofit & Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 2006, no. 35, pp. 310–319.

- O’Brien L., Townsend M., Ebden M. Environmental Volunteering: Motivations, Barriers and Benefits. Report to the Scottish Forestry Trust and Forestry Commission. 128 p.

- Krajňáková E., Šimkus A., Pilinkiene V., Grabowska M. Analysis of barriers in sports volunteering. Journal of International Studies, 2018, no. 11 (4), pp. 254–269. DOI:10.14254/2071-8330.2018/11-4/18

- Haski-Leventhal D., Meijs L.C.P.M., Lockstone-Binney L., Holmes K., Oppenheimer M. Measuring volunteerability and the capacity to volunteer among non-volunteers: Implications for social policy. Social Policy & Administration, 2017, no. 52 (5), pp. 1139–1167. DOI: 10.1111/spol.12342

- Lee K.-H., Alexander A.C., Kim D.-Y. Motivational factors affecting volunteer intention in local events in the United States. Journal of Convention & Event Tourism, 2013, no. 14 (4), pp. 271–292. DOI: 10.1080/15470148.2013.816646

- Stukas A.A., Snyder M., Clary E.G. Understanding and encouraging volunteerism and community involvement. The Journal of Social Psychology, 2016, no. 156, pp. 243–255.

- North D. Instituty, institutsional'nye izmeneniya i funktsionirovanie ekonomiki [Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance]. Nranslated from English by A.N. Nesterenko. Moscow: Fond ekonomicheskoi knigi “Nachala”, 1997. 180 p.

- Tambovtsev V.L. (Ed.). Institutsional'nye ogranicheniya ekonomicheskoi dinamiki: monografiya [Institutional Constraints of Economic Dynamics: Monograph]. Moscow: TEIS, 2009. 524 p.

- Hofstede G. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2011, no. 2 (1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

- Auzan A.A. et al. Sociocultural factors in economics: Milestones and perspectives. Voprosy Ekonomiki, 2020, no. 7, pp. 75–91 (in Russian).

- Lukka P., Paine A.E. An exclusive construct? Exploring different cultural concepts of volunteering. Voluntary Action, 2001, no. 3 (3), pp. 87–109.

- Grönlund H. et al. Cultural values and volunteering: A cross-cultural comparison of students’ motivation to volunteer in 13 countries. Journal of Academic Ethics, 2011, no. 9 (2), pp. 87–106.

- Aydinli A., Bender M., Chasiotis A. Helping and Volunteering across Cultures: Determinants of Prosocial Behavior. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2013, no. 5 (3). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1118

- Kolnick L., Mulder J. Strategies to improve recruitment of male volunteers in nonprofit agencies. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, 2007, no. 24 (2), pp. 98–104.

- Pevnaya M.V., Kuz'minchuk A.A. Opportunities for and barriers to the development of volunteer management in a Russian region (on the example of the Sverdlovsk Oblast). Voprosy upravleniya, 2016, no. 4, pp. 77–85 (in Russian).

- Southby K., South J. Volunteering, Inequalities and Barriers to Volunteering: A Rapid Review. Leeds Beckett University, 2016. 51 p.

- Bang H. Volunteer age, job satisfaction, and intention to stay. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 2015, no. 36, pp. 161–176.

- Rovers J., Japs K., Truong E., Shah Y. Motivations, barriers and ethical understanding of healthcare student volunteers on a medical service trip: a mixed method study. BMC Medical Education, 2016, 16:94. DOI: 10.1186/s12909-016-0618-0

- Nichols G., Grix J. 'How sport governance impacted on Olympic legacy: a study of unintended consequences and the “Sport Makers” volunteering programme'. Managing Sport and Leisure, 2016, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2016.1181984

- Mainar I., Servos C., Gil M. Analysis of volunteering among Spanish children and young people: Approximation to their determinants and parental influence. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary & Nonprofit Organizations, 2015, no. 26, pp. 1360–1390.

- Ishizawa H. Civic participation through volunteerism among youth across immigrant generations. Sociological Perspectives, 2015, no. 58 (2), pp. 264–285.

- Van Goethem A.A., van Hoof A., van Aken M.A.G., Orobio de Castro B., Raaijmakers Q.A.W. Socialising adolescent volunteering: How important are parents and friends? Age dependent effects of parents and friends on adolescents’ volunteering behaviours. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 2014, no. 35, pp. 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2013.12.003

- Youssim I., Hank K., Litwin H. The role of family social background and inheritance in later life volunteering: Evidence from SHARE-Israel. Research on Aging, 2015, no. 37 (1), p. 3.

- Petrina O.A. development of voluntary activity in Russia. Vestnik Universiteta, 2019, no. 4, pp. 163–167 (in Russian).

- Dyson S.E., Korsah K.A., Liu L.Q., O’Driscoll M., van den Akker O.B.A. Exploring factors having an impact on attitudes and motivations towards volunteering in the undergraduate nursing student population – A comparative study of the UK and Ghana. Nurse Education in Practice, 2021, no. 53: 103050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103050

- Einolf C.J. Gender differences in the correlates of volunteering and charitable giving. Nonprofit & Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 2011, no. 40, pp. 1092–1112.

- Fyall R., Gazley B. Applying social role theory to gender and volunteering in professional associations. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary & Nonprofit Organizations, 2015, no. 26, pp. 288–314.

- Fegan C., Cook S. Experiences of volunteering: a partnership between service users and a mental health service in the UK. Work, 2012, no. 43, pp. 13–21.

- Rotolo T., Wilson J. Social heterogeneity and volunteering in U.S. cities. Sociological Forum, 2014, no. 29 (2), pp. 429–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12091

- Breheny M., Pond R., Lilburn L.E.R. “What am I going to be like when I'm that age?”: How older volunteers anticipate ageing through home visiting. Journal of Aging Studies, 2020, no. 53: 100848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2020.100848

- Connolly S., O’shea E. The perceived benefits of participating in volunteering activities among older people: Do they differ by volunteer characteristics. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 2015, no. 39 (2), pp. 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2015.1024075

- Layton M.D., Moreno A. Philanthropy and social capital in Mexico. International Journal of Nonprofit & Voluntary Sector Marketing, 2014, no. 19 (3), pp. 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/nsvm.1498

- Enjolras B., Salamon L.M., Sivesind K.H., Zimmer A. The Third Sector as a Renewable Resource for Europe. Concepts, Impacts, Challenges and Opportunities. Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. 208 p.

- Anheier H.K., Salamon L.M. Volunteering in cross-national perspective: Initial comparisons. Law and Contemporary Problems, 1999, vol. 62, no. 4, pp. 43–65.

- The Palgrave Handbook of Volunteering, Civic Participation, and Nonprofit Associations. Ed. by D.H. Smith, R.A. Stebbings, J. Grotz. 1505 p.

- Baqir F. Evolution of Volunteerism in Pakistan. Strengthening Participatory Organizations (SPO). 2012. 27 р. https://www.academia.edu/24357196/Evolution_of_Volunteerism_in_Pakistan

- Geumchan Hwang, Kyu-soo Chung, 2018. "South Korea," Sports Economics, Management, and Policy. In: Kirstin Hallmann & Sheranne Fairley (ed.), Sports Volunteers Around the Globe, 2018. Pp. 225–235.

- Kudrinskaya L.A. Volunteering: Essence, functions, specifics. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya=Sociological Studies, 2006, no. 5, pp. 15–22 (in Russian).

- Kuptsova I.A. Culture of volunteering: Definition of the concept and main characteristics of the phenomenon. Pedagogika iskusstva. Available at: http://www.art-education.ru/electronic-journal/kultura-volontyorstva-opredelenie-ponyatiya-i-osnovnye-harakteristiki-fenomena

- Yakobson L.I., Sanovich S.V. Changing models of the Russian third sector: The phase of import substitution. Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost'=Social Sciences and Contemporary World, 2009, no. 4, pp. 21–34 (in Russian).

- Govaart M.M., van Daal H., Munz A., Keesom J. Volunteering Worldwide. Netherlands Institute of Care and Welfare, 2001. 257 p.

- Polterovich V.M. Transplantation of economic institutions. Ekonomicheskaya nauka sovremennoi Rossii, 2001, no. 3, pp. 24–50. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.285.12.1649 (in Russian).

- Lebedeva N.M., Tatarko A.N. Tsennosti kul'tury i razvitie obshchestva [Values of Culture and Development of Society]. Moscow: Izdatel'skii dom GU VShE, 2007. 528 p.

- Smith L.G. Mechanisms for public participation at a normative planning level in Canada. Canadian Public Policy / Analyse de Politiques, 1982, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 561–572.

- Åström J., Hinsberg H., Jonsson M.E., Karlsson M. Citizen centric e-participation. A trilateral collaboration for democratic innovation. Case studies on e-participation policy: Sweden, Estonia and Iceland. Tallinn: Praxis Center for Policy Studies, 2013. 47 p.

- Allhutter D., Aichholzer G. Public Policies on eParticipation in Austria. In: Macintosh A., Tambouris E. (Hrsg.) Electronic Participation (First International Conference on eParticipation [ePart]. 2009. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-03781-8_3

- Bazueva E.V. Sistema institutov gendernoi vlasti v ekonomike Rossii: osnovy teorii i metodologii: monografiya [The System of Institutions of Gender Power in the Russian Economy: Fundamentals of Theory and Methodology: Monograph]. Perm: Perm. gos. nats. issled. un-t, 2015. 456 p.

- Khasanzyanova, A. How volunteering helps students to develop soft skills. Int Rev Educ, 2017, pp. 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-017-9645-2

- Bazueva E.V. Features of the formation and use of human capital in the conditions of digitalization of the economy. In: Kompleksnoe razvitie territorial'nykh sistem i povyshenie effektivnosti regional'nogo upravleniya v usloviyakh tsifrovizatsii ekonomiki: mat-ly natsion. (vseross.) nauch.-prakt. konf. (8 noyabrya 2018 g., Orel) [Comprehensive Development of Territorial Systems and Improving the Efficiency of Regional Management in the Conditions of Digitalization of the Economy: Proceedings of the National (All-Russian) Research-to-Practice Conference (November 8, 2018, Orel)]. Orel: FGBOU VO “OGU imeni I.S. Turgeneva”, 2018. Pp. 469–473 (in Russian).

- Yakobson L.I. (Ed.). Faktory razvitiya grazhdanskogo obshchestva i mekhanizmy ego vzaimodeistviya s gosudarstvom [Drivers of Civil Society Development and Mechanisms of Its Interaction with the State]. Moscow: Vershina, 2008. 296 p.

- Kirdina S.G. X- i Y-ekonomiki: institutsional'nyi analiz [X- and Y-Economies: Institutional Analysis]. Moscow: Nauka, 2004. 256 p.

- Narushima M. ‘Payback time’: community volunteering among older adults as a transformative mechanism. Ageing and Society, 2005, no. 25, pp. 567–584. DOI: 10.1017/S0144686X05003661

- Maas S.A., Meijs L.C.P.M., Brudney J.L. Designing “National Day of Service” Projects to Promote Volunteer Job Satisfaction. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 2021, no. 50 (4), pp. 866–888. DOI: 10.1177/0899764020982664

- Shier M.L., Larsen-Halikowski J., Gouthro S. Characteristics of volunteer motivation to mentor youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 2020, no. 111: 104885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104885

- Jones K.S. Giving and volunteering as distinct forms of civic engagement: The role of community integration and personal resources in formal helping. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 2006, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 249–266.

- Clary E.G., Snyder M., Ridge R.D., Miene P.K., Haugen J.A. Matching messages to motives in persuasion: A functional approach to promoting volunteerism. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 1994, 24, 13, pp. 1129–1149.

- Young J., Passmore A. What is the occupational therapy role in enabling mental health consumer participation in volunteer work? Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2007, no. 54, pp. 66–69.