The employment quality potential of generation groups of workers and the economic sustainability of their households

Автор: Bobkov V.N., Odintsova E.V.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Public finance

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.16, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The exacerbation of external sanctions pressure on Russia in 2022, which continues to increase at present, has brought to the fore the national agenda of improving the quality of life and standard of living of Russians, achieving national benchmarks in this area and solving problems on the “inner circuit” in the face of new (including existential) challenges. There is a growing need for the development of a scientific and informational basis for the in-depth elaboration of effective responses to the challenges posed. The article presents the results of the research, which continues our developments in the field of studying the relationship between the quality of employment and living standards, focusing on the identification of features in generation groups: young people (up to 35 years), middle generation (36 years - retirement age), the older generation (retirement age). In this study, based on original developments, we have set out with the aim of identifying the unused potential of employment quality in generation groups of workers and its connection with the economic (un)sustainability of households, which determines their standard of living. The empirical basis was the data from the Russia Longitudinal Monitoring Survey of the HSE and the Comprehensive Monitoring of Living Conditions of the Population by Rosstat. The potential quality of employment of generation groups of workers is revealed, which is determined by the mismatch between education and employment (mismatch between the level of education and specialty, required in the workplace), the presence of precarious employment revealed on the basis of the indicators we have proposed. We consider the dynamics of economic sustainability of workers' households, determined on the basis of our developments and formed by the income from employment in generation groups of workers, as a whole and depending on the characteristics of the quality of employment. The results of this study allow us to update public policy decisions in the areas of employment and vocational education to improve the performance of the chain “education - employment - economic sustainability - standard of living”.

Generation groups, education, quality of employment, precarious employment, standard of living, economic sustainability of households, social standards, income from employment

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147241603

IDR: 147241603 | УДК: 330.59 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2023.3.87.10

Текст научной статьи The employment quality potential of generation groups of workers and the economic sustainability of their households

The research was carried out at the expense of the Russian Science Foundation, project no 22-28-01043, , at Plekhanov

New challenges to Russia’s development after February 2022 create risks to the national interests defined in the National Security Strategy of the Russian Federation – “preservation of the Russian people, development of human potential, improvement of the quality of life and well-being of citizens”1 and determine the need to actualize a set of program-targeted tools of public policy, aimed at the realization of national interests of the country.

The period of the COVID pandemic, the consequences of which in the field of employment “layered” on global transformation processes in the labor sphere (increasing role of digital competencies, expansion of nonstandard social and labor relations, etc.), clearly highlighted the increasing role of employment and its quality in maintaining and improving living standards of households. The new challenges of 2022, reflected in the Russian labor

Russian University of Economics.

market and employment2, create risks (changes in the number of the working in households, etc.) and opportunities (labor shortages, etc.) for the economic sustainability of Russian households and the improvement of their standard of living.

The need for further scientific developments in the study of the employment quality and its impact on the situation of households is of particular importance, actualizing the comprehension of the already accumulated scientific results.

The problematic of employment quality occupies an important place in the research agenda, including the study of its features in different segments of employment (standard/nonstandard) and economic sectors (formal/informal) (Baskakova, Soboleva, 2017; Leonidova, 2021; Chernykh, 2021; Peckham et al., 2022), for different groups of workers (Veredyuk, 2018; Bobkov et al., 2021), in the context of legal regulation in the labor sphere (Korshunova, 2020; Labor Relations..., 2022), and with the impact on other areas of life (Standard of Living and Quality..., 2022; Fokin, 2013).

Due to the complexity of the category “employment quality”, experts continue to develop an instrumental infrastructure for its qualitative-quantitative identification, and the reflection of the findings (Berten, 2022; Burchell et al., 2014; Munoz de Bustillo et al., 2011) to improve the objectivity and comprehensiveness of measurement, including considering the application to employment quality and social development policies. At the international level, a number of so-called indicator “frameworks” have been developed to measure various aspects of employment quality: the Decent Work Indicators of the International Labor Organization3, the statistical framework for measuring employment quality of the UN Economic Commission for Europe4 and for measuring and assessing jobs quality of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development5, etc.

The index approach to assessing the employment quality is proposed for practical application: the index of job quality, developed by the European Trade Union Institute for multidimensional (wages; forms of employment and job security; working time and work-life balance; working conditions; skills and career development; representation of collective interests) measurement of job quality in

European countries6; job quality indices (physical environment, intensity of work, quality of working time, social environment, skills and discretion, prospects, income from employment), which allow us grouping jobs according to their quality profiles7; employment quality deprivation index, providing indicators on the following dimensions: labor income, stability, security and employment conditions (Gonzalez et al., 2021); etc.

The peculiarity of our study is the consideration of the employment quality in connection with education. The authors focus on identifying the mismatch between education (level and specialty) and the requirements of the workplace. This problem of professional-qualification imbalance (“skills mismatch”), due to its scale and consequences, is the subject of study by both Russian and foreign researchers (Varshavskaya, 2021; Kolosova et al., 2020; Soboleva, 2022; Arvan et al., 2019; Erdogan, Bauer, 2020).

In addition, the employment quality is revealed through the identification of signs of precarious employment. Precarious employment in the context of the employment quality concept is a segment of employment with low quality due to the forced loss of labor, social and economic rights of workers (Precarious Employment..., 2019). The problematic of precarious employment is actively studied in the Russian and foreign research field (Kuchenkova, Kolosova, 2018; Precarious Employment..., 2019; From precarious employment..., 2022; Campbell, Price, 2016; Garcia-Perez et al, 2017; Padrosaet al., 2021; Standing, 2011), attention is focused on the consequences of such employment (reduced quality of employment, standard of living and quality of life, etc.) (Bobkov et al., 2021; Lewchuk et al., 2016; Popov, Solov’eva, 2019; Pun et al., 2022).

The economic sustainability of households, which is the second (but not in importance) aspect of the study in the framework of this article, is part of the problem field of research on living standards and the identification of population groups, differing in living standards, based on monetary criteria. These criteria for identification can be constructed based on objective (absolute and relative) and subjective approaches (Ovcharova, 2009; Tikhonova et al., 2018; Chen, Ravallion, 2013; Cutillo et al., 2022; Decerf, 2021; Mareeva, Lezhnina, 2019; Ravallion, Chen, 2019). We follow an absolute approach relying on consumer budgets of different affluence levels (Mozhina, 1993; Rzhanitsyna, 2019; Rimashevskaya et al., 1979; Sarkisyan, Kuznetsova, 1967; Deeming, 2011; Makinen, 2021; Penne et al., 2020) to distinguish different patterns of living standards (Standard of Living and Quality..., 2022). We also consider it advisable to link employment income to the criterion boundaries of standard of living models, thereby determining their required level (taking into account the dependency burden) to get into the strata of the population with different standard of living. This allows us to study employment and its quality, and the standard of living of households in their relationship.

This article continues our research into the generation characteristics of the relationship between employment quality and living standard. The aim of the work is to identify the unused potential of employment quality in generation groups of the workers and its relationship to the economic (un)sustainability of households, which determines their standard of living.

The scientific novelty of the study lies in the consideration of the impact of employment quality characteristics on the economic sustainability of households of generation group of the workers on the basis of our original findings.

The significance of this work consists in identifying the characteristics of employment quality that are sensitive to the economic sustai- nability of households and their quantitative identification, which allows us to update public policy decisions in the field of employment, vocational education to improve the performance of the chain “education – employment – economic sustainability – standard of living”.

Methodology of research and data

-

1. Generation perspective of employment. We focus our research on the generation groups of the workers: young people (up to 35 years), middle generation (36 years – retirement age) and older generation (retirement age). Singling out generation groups makes it possible to trace the dynamics of employment quality and the dynamics of economic sustainability determined by it at three different stages of the life cycle, related to the formation and realization of labor potential and the formation of standard of living (Bobkov et al., 2021).

-

2. Household economic sustainability of generation groups of the workers. We define economic sustainability as the financial situation sustainability, assessed on the basis of the original system of household per capita cash income (PCI) standards (Standard of Living and Quality..., 2022). The economic sustainability boundary, according to our developments, is the lower boundary of per capita income standards, identifying entry into the middle-income group (3.1 subsistence minimums – (SM) (Bobkov et al., 2021; Standard of Living and Quality..., 2022).

-

2.1. The main employment income boundary, that ensures the economic sustainability of households, which is 3.1 subsistence minimums of the working population (SMw). This is a boundary, that does not take into account dependency burdens in workers’ households. It was applied to older workers and youth and middle-generation workers with no underage children.

-

2.2. The boundary of basic employment income, that ensures the economic sustainability of households, is 3.9 SMw. This is a boundary that takes into account the minimum dependency burden in the households of workers, in the calculation of which the “model” dependency burden in the average family (two working and one child) and the savings on joint consumption were taken into account. This boundary applied to workers with underage children from the youth and middle generation.

-

3. Employment quality of generation groups of the workers. The study examined the economic (un) sustainability of households of generations groups of workers, depending on the employment quality. We focused on identifying the unused potential of employment quality, which was determined by the following criteria.

-

3.1. Matching the level of education to the required level in the workplace. To assess and measure the extent of discrepancies between the available level of education and the required level of education at the workplace in international practice different methods are used: subjective (based on self-assessment of employees), normative (based on the classifiers of professions (occupations), in which they are correlated with the levels of qualification, determined on the basis of educational levels), empirical (statistical, identifying average (modal) level of education for professions), etc.10 In this study, we applied the normative method. The assessment was based on the analysis of the distribution of the employed by occupational groups (groups of occupations), allocated by the All-Russian Classifier of Occupations (AKO)11, and the level of education (correlated in the AKO with a certain level of qualification). When comparing the level of education available to employees with the required level of education in the workplace (the main employment), the identification of its (1) compliance, (2) redundancy, (3) insufficiency was carried out.

-

3.2. Compliance of the work to the received specialty. We considered how much the available employment (main employment) corresponds to the received specialty: a) work fully corresponds to the received specialty; b) work in a close specialty; c)

-

-

3.3. Absence/presence of the precarious employment manifestation. In order to identify precarious employment, we used the list of indicators previously verified by the authors (Bobkov et al., 2022).

-

3.3.1. Precarious employment by type of contractual agreements – employment on the basis of 1) verbal agreement without paperwork; 2) civil law contract or 3) labor contract (service contract) for a certain period of time; 4) employment not for hire in the informal sector.

-

3.3.2. Precarious employment by its terms – 5) forced unpaid vacation at the employer’s initiative; 6) absence of paid vacation; 7) reduction in wages or reduction of working hours by the employer; 8) wage arrears; 9) unofficial (partial or full) income from main employment; 10) working hours deviating from the standard: the length of the working week is more than 40 hours or not more than 30 hours (at the main place of work).

-

Thus, the households, in which the level of PCI is not lower than 3.1 SM, i.e. they belong to the middle- and high-income groups by cash income, are defined as economically stable. Accordingly, households with a PCI lower than 3.1 SM, i.e., those who are poor, low-income, or below middle in terms of cash income, are classified as economically unstable.

We consider economic sustainability in relation to employment; we analyze whether the economic sustainability of households of generation groups of the workers is ensured at the expense of income from main employment.

The formation of standard of living of households is linked to main employment for the following reasons. First, the main source of income, as follows from the official statistics, is wages8. Second, our study focuses on the employed, and according to Rosstat, 98% of the employed have only one job9, so their household income is mainly formed by income from primary employment. Third, in examining the relationship between household income and employment income, we assume that economic sustainability in employed households should be achieved through their main employment, rather than through multiemployment, welfare payments, etc.

The assessment of the income level from main employment was differentiated for workers of different generational groups. Two boundaries of employment income were applied according on the presence of dependency burden and generation group.

work not in the specialty. Assessment of compliance was based on the subjective method: workers’ selfassessments on a dedicated “scale” (a) – (c) were taken into account.

On the basis of two criteria, the employment quality potential of workers of generation groups was evaluated in terms of the presence of so-called “vertical” (criterion 3.1) and/or “horizontal” (criterion 3.2) discrepancies between education and employment. They also allow us to make conclusions about the effectiveness of the educational potential in employment realization.

Among the manifestations of precarious employment, we also consider the employment income level (Bobkov et al., 2022), but in accordance with the intention of this study it was not included in the list of precarious employment indicators by its conditions (3.3.2), but was considered as an independent, resulting aspect of the study, characterizing the employment quality.

The presence of precarious employment manifestations among workers of the generation groups was taken into account in the following way.

Workers with precarious employment by the type of contractual agreements (presence of any indicator from the list (1) – (4) and workers with precarious employment by its conditions (presence of three or more indicators from the list (5) – (10) were identified.

The empirical basis of the study was formed on the basis of the following data (the most relevant data available for processing at the time of the study):

-

(1) data from the Russia Longitudinal Monitoring Survey of the HSE University12 (hereinafter – RLMS): data from the 30th round of RLMS (September 2021 – January 2022), and the 10th round of RLMS (October – December 2001)13;

-

(2) microdata from the Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions conducted by Rosstat in May – June 202214 (hereinafter – CSLS–2022).

Thus, in this study, we record the situation in the period after the pandemic and the exacerbation of external sanctions pressure on Russia in 2022, which continues to grow at the present time.

In the course of the study, the CSLS and RLMS databases were used as “complementary” to each other, taking into account the “power” of each of them – the absence of data necessary for analysis in one database was “compensated” by data available in the other one. The RLMS database was the main one for the assessment, because it more fully presents the list of indicators required for the purposes of the study. The CSLS database was used as an additional database to compensate for the absence/insufficiency of data in the RLMS database15.

From each database, a sample was drawn – individuals aged 15 or older, who were employed16. Next, we identified generation groups – young people (up to 35 years), the middle generation (36 years – retirement age), the older generation (retirement age), which were further analyzed in accordance with the concept of research.

Main results of the study

The results obtained show generation specifics of the employment quality and economic sustainability of workers’ households.

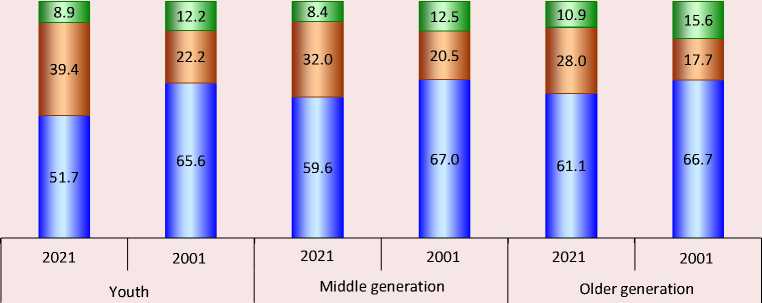

In the generation groups of the workers 50–60% had an education level, which corresponded to the level required at the workplace (Fig. 1) . In the transition from the youth group (51.7%) to the older generation (61.1%), the proportion of workers, whose education level corresponded to the complexity of the workplace, increased.

A comparison of two measurements of the state of education level compliance with job requirements (2021 – current data; 2001 – the beginning of the country’s economic recovery after the systemic crisis of the 1990s) showed that this “model” of educational potential realization in employment has become less common in the generation groups of the workers, the greatest

Figure 1. Matching of the available level of education with the required level of education in the workplace in generation groups of the workers, 2001 and 2021, %

□ Compliance □ Redundancy □ Insufficiency

According to: data from the 30th and 10th round of the RLMS. We used data, which recorded belonging to the group of occupations according to the classifier of occupations and the education level.

negative dynamics are observed among young people (-13.9 p.p.). Young people began to adapt in the labor market, more often (+17.2 p. p.) turning to another “model” – with excessive education levels, implementing (for various reasons) the education level in less qualified employment (39.4% in 2021 and 22.2% in 2001). The potential for “excess” education by 2021 also increased in the other two generation groups of the workers: the middle generation by 11.5 p.p. (32.0% in 2021), and the older generation by 10.3 p.p. (28.0% in 2021).

At the same time, a significant number of workers in all generation groups are employed in jobs, which require a higher education level (insufficient education level for the complexity of the job). In the youth group of employment their share was 8.9% in 2021, in the middle group – 8.4%, in the older generation group insufficient education level compared to the qualification requirements had 10.9%. In 2021 this disproportion decreased: in youth – by 3.3 p.p., in the middle generation – by 4.1 p.p., in the older generation – by 4.7 p.p.

Cumulatively, the share of workers, whose educational potential (education level) is not fully used or is insufficient for the job complexity, was 48.3% in the youth generation, 40.4% in the middle generation and 38.9% in the older generation (2021). These generation groups of the workers have so-called “vertical” (education level) mismatches between education and employment.

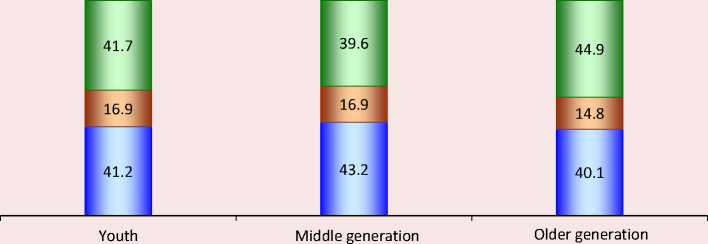

“Horizontal” mismatches – work outside one’s specialty – are also widespread. In generation groups of the workers, only about 40% (2022) worked in their specialty (Fig. 2). Among young people, 41.2% worked in their specialty, almost as many (41.7%) were employed outside their specialty, and 16.9% were employed in a closely related specialty.

In the middle generation, the share of those, who work in their specialty, increases (43.2%). The share of those, who work in a close specialty, corresponds to the share in the youth group (16.9%) and the share of those, who work in a non-specialty, is the lowest among the generation groups (39.6%).

Figure 2. Distribution of the employed generation groups, depending on the compliance of work with the received specialty, 2022, %*

□ Work outside one’s specialty

□ Work in a close specialty

□ Work in one's specialty (the work fully corresponds to the received specialty)

* The proportion of workers, who found it difficult to answer, in the generational groups is not presented, was 0.2–0.3%.

According to: CSLS–2022 data. We used information about the matching of the main job to the received specialty (the answers “Yes, this job fully corresponds to the received specialty”, “Yes, this job is close to the specialty”, “No, this job is not a specialty” were taken into account).

The older generation has the highest proportion of out-of-specialty workers (44.9%) and the lowest proportion of in-specialty workers (40.1%) relative to the other two generation groups. Working in a close profession in the older generation is 14.8%, which is lower, than among the youth and the middle generation.

In general, more than 70% (2022) of generation groups of the workers revealed unrealized potential of employment quality (Tab. 1) . In the older generation 76.0% had “vertical” and/or “horizontal” mismatches between education and employment, in the middle generation their share was 76.7%, and in the youth group it reached 77.3%.

At the same time, a significant share of workers was characterized by employment with both “horizontal” and “vertical” mismatches in educational potential. They worked not in their specialty with the education level not corresponding to that required at the workplace. Among young people the share of such workers was 33.0%, in the middle generation it is slightly lower – 32.2% and in the older generation it reaches a maximum – 38.4%.

Thus, a large part of the workers (more than 70%) of the three generation groups under consideration have unrealized opportunities to improve the quality of employment in terms of more complete use of the received specialty and/or qualification (education level). Of these, one third or more of the workers found both specialty and qualification were not in demand for the available employment.

Having implemented their educational potential in employment with different results, workers may additionally face a decrease in the employment quality due to the presence of precarious employment manifestations (Tab. 2) . Youth (18.3%) and older generation (17.6%) employment is more likely to be precarious due to the type of contractual arrangements, than middle-generation workers (15.3%). They work for hire, but not under an open-ended employment contract (employed under a civil law contract or labor contract (service contract) for a certain period of time) or without formal registration; or employed not for hire in the informal sector.

Youth workers (8.4%) are more likely to experience precarious employment by its terms. The older (6.0%) and middle (5.5%) generations are less likely to experience a decline in employment quality due to the presence of three or more indicators of precarious employment.

Thus, unrealized employment quality potential due to the presence of manifestations of precarious employment, indicating low employment quality, was identified in less than 10–20% of generation group of the workers (depending on the type of contractual agreements or employment conditions assessment).

Basic employment incomes for the vast majority of workers in all three generation groups, as the results obtained show, do not ensure the economic sustainability of households (Tab. 3) . The greatest risks that employment will not be able to ensure the

Table 1. Distribution of employed generation groups depending on the relevance of the job obtained and the compliance of the available education with the required level of education at the workplace, 2022, %

|

Mismatches |

Youth |

Middle generation |

Older generation |

|

Work not in their specialty and/or their education level does not match the required in the workplace, including: |

77.3 |

76.7 |

76.0 |

|

Work not in their specialty with education level, which does not correspond to the required in the workplace |

33.0 |

32.2 |

38.4 |

|

According to: CSLS–2022 data. We used information about the matching of the main job to the received specialty (the answers “Yes, this job fully corresponds to the received specialty”, “Yes, this job is close to the specialty”, “No, this job is not a specialty”) and also information the belonging to the group of occupations according to the classifier of occupations and the education level. |

|||

Table 2. Presence of manifestations of precarious employment in the employed generation groups, 2021–2022, %

|

Employment |

Youth |

Middle generation |

Older generation |

|

Precarious employment by type of contractual arrangements (employment for hire based on verbal agreement without paperwork, civil law contract or labor contract (service contract) for a certain period of time); employment not for hire in the informal sector)* |

18.3 |

15.3 |

17.6 |

|

Precarious employment by its conditions (presence of three or more indicators** of precarious employment conditions)*** |

8.4 |

5.5 |

6.0 |

|

According to: data from the 30th round of the RLMS and the CSLS–2022. * We used the information in the CSLS database on the working conditions of the employed for hire (the answers “Based on verbal agreement, without paperwork”, “Based on a civil law contract”, “Based on a labor contract (service contract) – for a certain period of time”) and also on work in the informal sector for the self-employed were taken into account. ** We took into account the following indicators: forced unpaid vacation at the employer’s initiative; absence of paid vacation; reduction of wages or reduced working hours by the employer; wage arrears; unofficial (partial or full) income from main employment; working hours, which deviate from the standard: working week of more than 40 hours or not more than 30 hours (in the main place of work). The indicators, characterizing precarious employment by its conditions, did not include the indicator of income from employment, which does not provide a stable economic situation of households. It was considered as an independent, resulting aspect of the study, characterizing the employment quality. Therefore, the share of workers with precarious employment due to its conditions has a lower value, different from its values obtained, when taking into account this indicator among others characterizing precarious employment conditions (see “Discussion of the results”). *** The following questions in the RLMS database were used: “During the last 12 months, did the administration send you on forced unpaid vacation?” (answers “Yes” were taken into account), “Have you been on paid vacation during the last 12 months?” (answers “No” were taken into account), “During the last 12 months, have you had your salary reduced or have your working hours been reduced against your wishes?” (the answers “Yes” were taken into account), “Does your company currently owe you any money, which for various reasons was not paid on time?” (answers “Yes” were taken into account), “Do you think all this money was spent officially?” (the answers “Some officially, some not’, “All – unofficially” were taken into account), “How many hours on average does your regular work week last?” (the duration of the work week was considered more than 40 hours or not more than 30 hours). |

|||

economic sustainability of households are found among older workers (87.3%), whose income from employment is not the only source of income, and social benefits (pensions) can “smooth out” the sharpness of their household income situation. Among young people these risks are lower, than in the older generation – 82.3%, in the middle generation they decrease to 77.8%.

Accordingly, the chances of ensuring the economic sustainability of workers’ households at the expense of income from main employment are highest for middle-generation workers (22.2%), the chances are almost half as high for the older generation (12.7%) and for young people they are 17.7%.

During a review of the employment income levels of generation groups of the workers by generalized characteristics of employment quality, it is found that regardless of these, employment income for the vast majority (over 70–80%) of workers does not provide economic sustainability for households (see Tab. 3). This is a demotivating factor for the development of employees’ labor potential, professional development, professional growth, etc.

We should note, that for young workers, the mismatch between education and employment increases the chances of economic sustainability for households. In contrast, in the older generation, economic sustainability of households is more likely to result from employment in accordance with education. The absence of precarious employment manifestations for older and younger workers is more likely to lead to the economic sustainability of their households. In the middle generation there are no noticeable differences in the ability of employment to ensure the economic sustainability of households, depending on these characteristics of the employment quality.

Table 3. Distribution of the employed generation groups by standards of income from basic employment in general and according to the quality of employment (compliance of education and employment; presence of precarious employment manifestations), 2021, %

|

Generation group |

Level of income from main employment* |

|

|

Does not ensure the economic sustainability of households |

Ensure the economic sustainability of households |

|

|

Youth |

||

|

Total |

82.3 |

17.7 |

|

Depending on the employment quality |

||

|

Matching between education and employment** |

||

|

Matches |

83.4 |

16.6 |

|

Does not match |

81.5 |

18.5 |

|

Presence of precarious employment manifestations (by type of contractual arrangements and/or by terms of employment) |

||

|

Available |

83.2 |

16.8 |

|

Not available |

80.4 |

19.6 |

|

Middle generation |

||

|

Total |

77.8 |

22.2 |

|

Depending on the employment quality |

||

|

Matching between education and employment** |

||

|

Matches |

77.2 |

22.8 |

|

Does not match |

78.8 |

21.2 |

|

Presence of precarious employment manifestations (by type of contractual arrangements and/or by terms of employment) |

||

|

Available |

77.5 |

22.5 |

|

Not available |

78.1 |

21.9 |

|

Older generation |

||

|

Total |

87.3 |

12.7 |

|

Depending on the employment quality |

||

|

Matching between education and employment** |

||

|

Matches |

86.0 |

14.0 |

|

Does not match |

89.9 |

10.1 |

|

Presence of precarious employment manifestations (by type of contractual arrangements and/or by terms of employment) |

||

|

Available |

88.9 |

11.1 |

|

Not available |

85.3 |

14.7 |

|

* When assessing the income from main employment (information on the amount of money received at the main place of work was taken into account), differentiated income limits were taken into account: for older workers, and workers from the youth and middle generation with no underage children – without considering the dependency burden (3.1 SMw); for youth and middle generation workers with underage children – with considering the dependency burden (3.9 SMw). ** The presence of “vertical” mismatches between education and employment was taken into account. According to: data from the 30th round of the RLMS. |

||

Discussion of the results

The data obtained during the study confirm the relevance of the problem of vocational and qualification imbalance, which is widely represented in Russian employment, but also exists in other countries17 (Soboleva, 2022). The results of the study show that more than 70% of generation groups of employed/workers do not work in their specialty and/or their education level does not match the required level of education in the workplace. The employment of these generation groups of the workers identifies the so-called “skills mismatch”. This refers to “vertical” and “horizontal” mismatches between education and employment18. There are international comparisons on this issue, which confirms its importance for improving employment effectiveness. Thus, Russia (more than 40% of the labor force) is among the countries with the highest size of the “skills mismatch”, the impact of which for country economies leads not only to losses in labor productivity (estimated at an average 6%), losses in GDP (global GDP losses are estimated at $5 trillion), but also to social consequences (uncertainty and concern of workers about their future employment, career development, income levels, etc.)19. The consequences of this problem actualize the need for a comprehensive solution and harmonization of education and employment.

The mismatch between the available education level and the required education level at the workplace, in our opinion, should be analyzed through the contradictions, which arise and are resolved as a result of this mismatch. We believe, that the partially developed scale of unused potential of education is the result of an objective process of “imbalance” between the qualifications of the labor force and its number and complexity of jobs and their number. Over the past 20 years the unused potential of the so-called ”excess” education has increased significantly in all generation groups: in the youth – by 17.2 p.p. (significantly more, than in other generation groups); in the middle generation – by 11.5 p.p.; in the working older generation – by 10.3 p.p. At the same time, the disproportion manifested in the lack of vocational education for the complexity of jobs has decreased during this time: in the youth – by 3.3 p.p.; in the middle generation – by 4.1 p.p.; in the working seniors – by 4.7 p.p.

In this aspect, the outpacing growth of education, compared to the complexity of jobs, in our view, is a positive process in the development of any social system. This is primarily due to the fact that a higher level, and most importantly, the education quality becomes a social elevator for people, it creates opportunities to move to higher strata in terms of income from employment and the standard of living and quality of life. Education allows people to develop and meet their needs more fully and creates conditions for greater economic sustainability of workers’ households. The outpacing growth in education compared to the increasing complexity of jobs is also a driver of scientific and technological progress.

If the development of a person/labor force is ahead of the complexity of his environment, in our case the complexity of the work environment, a person (society) can manage its development. Regarding the employment quality and its performance, this means that a higher education level (provided that a higher level of formal education corresponds to its higher quality) compared to the complexity of jobs creates opportunities for their transformation, improving the quality (complexity) and increasing labor productivity, and therefore, other things being equal, increasing employment income and economic stability, living standards of households.

Part of the problem of the imbalance between the qualifications of the labor force and its size, on the one hand, and, the complexity of jobs and their number, on the other hand, is the result of a number of mistakes in public policy for the development of high-tech and knowledge-intensive sectors of the Russian economy. In the post-Soviet period, until 2014, there were no normal conditions for the production of complex knowledge-intensive products, allowing us to have a normal profitability, clear prospects and to attract highly qualified specialists. In this situation, there was a mass reassignment of graduates with technical, natural science and a number of social science specialties, and their movement to higher-paying sectors of the economy.

Other reasons for the imbalance between the education of workers and the complexity of jobs are a variety of circumstances: territorial mismatches (either a workers’ shortage or a shortage of jobs in a particular area of employment); a change in professional specialization by workers who have “discovered” new abilities and realize more acceptable for them areas “application” of their knowledge, skills and experience; lack of competitiveness in the basic profession; health conditions, etc.

As a consequence of all this, the problems of harmonization of professional education and complexity of jobs, in our opinion, must be solved taking into account all the diverse circumstances, identifying their specific causes and consequences, their positive and negative aspects and ways to harmonize them, including taking into account sectoral and territorial specifics and in connection with improving the economic stability of workers’ households.

The unused employment quality potential of generation group of the workers identified in the study, determined by its decline due to the type of contractual agreements and employment conditions, illustrates the prevalence of the precarious employment problem, including its risks for different socio-demographic, professional and territorial population groups (Precarious Employment..., 2019; Precarious Employment..., 2021).

The consequences of precarious employment, which spread to the living standards of workers’ households, leading to a decline in its monetary indicators (Bobkov et al., 2021; Kuchenkova, Kolosova, 2018; Lewchuk et al., 2016), and also the precarization of all aspects of life (From Precarious Employment..., 2022), require its further study in the paradigm “from employment quality to quality of life”, including the characteristics of workers in different generation groups and their households.

A significant negative impact of low employment income on all aspects of workers’ and their households’ lives is noteworthy. Accounting of employment income as an indicator of its sustainability or unsustainability leads to differences in the results of estimating the scale of precarious employment. In our study, as mentioned above, this indicator was not included in the verified list of indicators of precarious employment. It was considered as an independent, resulting aspect, characterizing the quality of employment.

If we take into account its influence as a part of employment conditions indicators, and it is such, then the scale of precarious employment in generation groups by employment conditions would be, in contrast to the data given in Table 2: among the youth – 13.9% (1.6-fold more), among the middle generation – 13.9% (2.5-fold more), among the older generation – 13.3% (2.2-fold more). It follows, that the problem of low income from employment has an important independent significance. It characterizes both precarious and stable employment and indicates an undervalued labor force, so it becomes a priority to improve the employment quality and quality of life of Russians.

Conclusion

The conducted research has shown, that in generation groups of the workers, there are large scales of unrealized potential of employment quality due to the mismatch of jobs with the educational potential of the employed and the precarity of their employment, which directly affects large scales of economic instability of different generation groups’ households.

The results of the study demonstrate the importance for the national agenda of Russia of increasing the efficiency of the use of workers’ labor potential and increasing income from employment as the main source of formation of households’ economic sustainability, increasing the standard of living and quality of their lives.

Our study contributes to the development of scientific knowledge about the relationship between the employment quality and economic sustainability of workers’ households, complements the scientific information base with new data obtained on the basis of our developments about generation features of the relationship between the basic components of the quality and standard of living. The results of the study, demonstrating the specifics for workers of three generation groups – the youth, middle and older generation, can be in demand to improve public policy to harmonize vocational education and employment quality; increase the effectiveness of the chain “education – employment – economic sustainability – standard of living” and influence through improving the employment quality on the quality of life of Russians, including taking into account the characteristics of workers of different generation groups and their households.

Список литературы The employment quality potential of generation groups of workers and the economic sustainability of their households

- Arvan M.L., Pindek S., Andel S.A. et al. (2019). Too good for your job? Disentangling the relationships between objective overqualification, perceived overqualification, and job dissatisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 115, 103323. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103323

- Baskakova M.E., Soboleva I.V. (2017). Employment quality and observance of labour rights in the sphere of small business. Rossiya i sovremennyi mir=Russia and the Contemporary World, 2(95), 57–74 (in Russian).

- Berten J. (2022). Producing decent work indicators: Contested numbers at the ILO. Policy and Society, 41(4), 458–470. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/polsoc/puac017

- Bobkov V.N. (Ed.). (2019). Neustoichivaya zanyatost’ v Rossiiskoi Federatsii: teoriya i metodologiya vyyavleniya, otsenivanie i vektor sokrashcheniya [Precarious Employment in the Russian Federation: Theory and Methods of Identification, Evaluation and the Vector of Decreasing]. Moscow: KNORUS.

- Bobkov V.N., Loktyukhina N.V., Shamaeva E.F. (Eds.). (2022). Uroven’ i kachestvo zhizni naseleniya Rossii: ot real’nosti k proektirovaniyu budushchego [Standard of Living and Quality of Life in Russia: From Reality to Projecting the Future]. Moscow: FCTAS RAS.

- Bobkov V.N., Odintsova E.V., Bobkov N.V. (2021). The impact of the level and quality of employment in generational groups on the distribution of the working-age population by per capita income. Sotsial’no-trudovye issledovaniya=Social and Labor Research, 44(3), 8–20. DOI: 10.34022/2658-3712-2021-44-3-8-20 (in Russian).

- Bobkov V.N., Odintsova E.V., Ivanova T.V., Chashchina T.V. (2022). Significant indicators of precarious employment and their priority. Uroven’ zhizni naseleniya regionov Rossii=Living Standards of the Population in the Regions of Russia, 18(4), 502–520. DOI: https://doi.org/10.19181/lsprr.2022.18.4.7 (in Russian).

- Burchell B., Sehnbruch K., Piasna A. et al. (2014). The quality of employment and decent work: Definitions, methodologies, and ongoing debates. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 38(2), 459–477. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bet067

- Campbell I., Price R. (2016). Precarious work and precarious workers: Towards an improved conceptualization. The Economic and Labor Relations Review, 27(3), 314–332. DOI:10.1177/1035304616652074

- Chen S., Ravallion M. (2013). More relatively-poor people in a less absolutely-poor world. Review of Income and Wealth, 59(1), 1–28. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.2012.00520.x

- Chernykh E.A. (2021). Socio-demographic characteristics and quality of employment of platform workers in Russia and the world. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 14(2), 172–187. DOI: 10.15838/ esc.2021.2.74.11

- Cutillo A., Raitano M., Siciliani I. (2022). Income-based and consumption-based measurement of absolute poverty: Insights from Italy. Social Indicators Research, 161, 689–710. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02386-9

- Decerf B. (2021). Combining absolute and relative poverty: Income poverty measurement with two poverty lines. Social Choice and Welfare, 56, 325–362 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-020-01279-7

- Deeming C. (2011). Determining minimum standards of living and household budgets: Methodological issues. Journal of Sociology, 47(1), 17–34. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783310386825

- Erdogan B., Bauer T.N. (2020). Overqualification at work: A review and synthesis of the literature. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8, 259–283. DOI: 10.1146/ annurev-orgpsych-012420-055831

- Fokin V.Y. (2013). Impact of the geographical differentiation of the quality and security of population employment on the territorial shrinkage in Perm Krai rural areas. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 6(30), 136–147.

- García-Pérez C., Prieto-Alaiz M., Simón H. (2017). A new multidimensional approach to measuring precarious employment. Social Indicators Research, 134, 437–454. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1447-6

- González P., Sehnbruch K., Apablaza M. et al. (2021). A multidimensional approach to measuring quality of employment (QoE) deprivation in six Central American countries. Social Indicators Research, 158, 107–141. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02648-0

- Kolosova A.I., Rudakov V.N., Roshchin S.Yu. (2020). The impact of job-education match on graduate salaries and job satisfaction. Voprosy ekonomiki=Economic Issues, 11, 113–132. DOI: 10.32609/0042-8736-2020-11-113-132 (in Russian).

- Korshunova T.Yu. (2020). Remote work agreement as a way to formalize atypical labour relations. Zhurnal rossiiskogo prava=Journal of Russian Law, 2, 112–125. DOI: 10.12737/jrl.2020.021 (in Russian).

- Kuchenkova A.V., Kolosova E.A. (2018). Differentiation of workers by features of precarious employment. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: ekonomicheskie i sotsial’nye peremeny=Monitoring of Public Opinion: Economic and Social Changes, 3, 288–305. DOI: 10.14515/monitoring.2018.3.15 (in Russian).

- Leonidova G.V. (2021). The quality of labor potential and employment in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sotsial’noe prostranstvo=Social Area, 7(5). DOI: 10.15838/sa.2021.5.32.2 (in Russian).

- Lewchuk W., Laflèche M., Procyk S. et al. (2016). The precarity penalty: How insecure employment disadvantages workers and their families. Alternate Routes, 27, 87–108.

- Lyutov N.L., Chernykh N.V. (Eds.). (2022). Trudovye otnosheniya v usloviyakh razvitiya nestandartnykh form zanyatosti [Labor Relations in the Development of Non-standard Forms of Employment]. Moscow: Prospekt.

- Mäkinen L. (2021). Different methods, different standards? A comparison of two Finnish reference budgets. European Journal of Social Security, 23(4), 360–378. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/13882627211048514

- Mareeva S., Lezhnina Y. (2019). Income stratification in Russia: What do different approaches demonstrate? Studies of Transition States and Societies, 11(2), 23–46.

- Mozhina M.A. (1993). Methodological issues of determining the subsistence minimum. Ekonomist=Economist, 2, 44–52 (in Russian).

- Muñoz de Bustillo R., Fernández-Macías E., Esteve F. et al. (2011). E pluribus unum? A critical survey of job quality indicators. Socio-Economic Review, 9(3), 447–475. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwr005

- Ovcharova L.N. (2009). Teoreticheskie i prakticheskie podkhody k otsenke urovnya, profilya i faktorov bednosti: rossiiskii i mezhdunarodnyi opyt [Theoretical and Practical Approaches to Assessing the Level, Profile and Factors of Poverty: Russian and International Experience]. Moscow: M-Studio.

- Padrosa E., Bolíbar M., Julià M. et al. (2021). Comparing precarious employment across countries: Measurement invariance of the employment precariousness scale for Europe (EPRES-E). Social Indicators Research, 154, 893–915. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02539-w

- Peckham T., Flaherty B., Hajat A. et al. (2022). What does non-standard employment look like in the United States? An empirical typology of employment quality. Social Indicators Research, 163, 555–583. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02907-8

- Penne T., Cornelis I., Storms B. (2020). All we need is… reference budgets as an EU policy indicator to assess the adequacy of minimum income protection. Social Indicators Research, 147, 991–1013. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02181-1

- Popov A.V., Soloveva T.S. (2019). Analyzing and classifying the implications of employment precarization: Individual, organizational and social levels. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 12(6), 182–196. DOI: 10.15838/esc.2019.6.66.10

- Pun N., Chen P., Jin S. (2022). Reconceptualizing youth poverty through the lens of precarious employment during the pandemic: The case of creative industry. Social Policy and Society, 1–16. DOI:10.1017/S1474746421000932

- Ravallion M., Chen S. (2019). Global poverty measurement when relative income matters. Journal of Public Economics, 117, 104046. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2019.07.005

- Rimashevskaya N.M. et al. (1979). Potrebnosti, dokhody, potreblenie. Metodologiya analiza i prognozirovaniya narodnogo blagosostoyaniya [Needs, Income, Consumption. Methodology of Analysis and Forecasting of National Welfare]. Moscow: Nauka.

- Rzhanitsyna L.S. (2019). Standard of economic sustainability of family a new orientation of income policy. Narodonaselenie=Population, 22(1), 122–127. DOI: https://doi.org/10.19181/1561-7785-2019-00009 (in Russian).

- Sarkisyan G.S., Kuznetsova N.P. (1967). Potrebnosti i dokhod sem’i [Needs and Income of the Family]. Moscow: Ekonomika.

- Soboleva I.V. (2022). Professional and qualification imbalance as a challenge to economic and social security. Ekonomicheskaya bezopasnost’=Economic Security, 5(3), 989–1008. DOI: 10.18334/ecsec.5.3.114898 (in Russian).

- Standing G. (2011). The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Tikhonova N.E., Lezhnina Yu.P., Mareeva S.V. et al. (2018). Model’ dokhodnoi stratifikatsii rossiiskogo obshchestva: dinamika, faktory, mezhstranovye sravneniya [The Model of Income Stratification of Russian Society: Dynamics, Factors, Intercountry Comparisons]. Moscow; Saint Petersburg: Nestor-Istoriya.

- Toshchenko Zh.T. (Ed.). (2021). Prekarnaya zanyatost’: istoki, kriterii, osobennosti [Precarious Employment: Origins, Criteria, Features]. Moscow: Ves’ Mir.

- Toshchenko Zh.T. (Ed.). (2022). Ot prekarnoi zanyatosti k prekarizatsii zhizni [From precarious employment to precarization of life]. Moscow: Ves’ Mir.

- Varshavskaya E.Ya. (2021). Overqualification of Russian employees: Scale, determinants, consequences. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya=Sociological Studies, 11, 37–48. DOI: 10.31857/S013216250016075-5 (in Russian).

- Veredyuk O.V. (2018). Quality of youth employment in Russia: Analysis of job satisfaction assessments. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: ekonomicheskie i sotsial’nye peremeny=Monitoring of Public Opinion: Economic and Social Changes, 3, 306–323. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14515/monitoring.2018.3.16 (in Russian).