The French economy between the COVID-19 pandemic and a new geopolitical situation: relapsing into the crisis or overcoming it?

Автор: Sapir Jacques

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Foreign experience

Статья в выпуске: 5 т.15, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The French economy, while still recovering from the COVID-19 crisis, is currently dealing with special problems that have emerged due to the new geopolitical situation. Signs of weakness in the French economy at the beginning of the year may turn into an actual recession in 2023. The latest forecasts are particularly pessimistic in this regard. Since Russia has terminated its oil and gas deliveries after the sanctions imposed by the European Union, the French economy is at risk of serious inflation issues. Delivery interruptions can have significant negative consequences for France primarily due to their indirect impact resulting from the influence on its neighbor, Germany. The inflation that has hit the French economy and other economies of the European Unions is a kind of inflation caused by deficit rather than excessive demand. The French government, which spent considerable amount of money to protect people and businesses during the COVID-19 crisis, is faced with the need to provide significant assistance again. Both fiscal and monetary policy will be disrupted. A sharp increase in public debt is also expected. France has encountered an unprecedented economic situation, when the rules of a market economy seem powerless in the face of incoming problems. Economic planning, similar to the one that was used from 1946 to the end of the 1960s, probably represents the best opportunity for the French economy to adapt to the consequences of the new geopolitical situation.

Inflation, shortage, growth, uncertainty, household expenses, administrative expenses,

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147239123

IDR: 147239123 | УДК: 332.1(075.8) | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2022.5.83.3

Текст научной статьи The French economy between the COVID-19 pandemic and a new geopolitical situation: relapsing into the crisis or overcoming it?

By the end of the first half of 2022, the French economy was at a crossroads. Moving toward recovery from the various shocks caused by COVID-19 and pandemic-related restrictions, it now faces the consequences of the situation in Ukraine and the interaction of sanctions and counter-sanctions, in other words, the economic consequences of restructuring international trade and what has been called globalization. The latter has already been the subject of much criticism (Sapir, 2009a). Today, however, globalization is seriously threatened by the formation of two opposing blocs in the world1. In this context, the French economy is experiencing significant exogenous shocks in both its growth and inflation. They are already recognized at the highest level, for example by the Bank of France2 or the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE)3. Undoubtedly, these shocks have the potential to disrupt the French economy.

But beyond that, the French economy is still struggling with the aftermath of the 2008–2010 crisis (Streeck, 2018), after which it became crippled. The economy has never fully overcome the consequences (Sapir, 2009b). Thus, the problems it faces and will face even more by the end of 2022 cannot be attributed solely to external shocks.

But many economists and ministry officials in charge of economics and finance tend both to minimize the impact of these external shocks and to overlook that they are hitting the economy that has been changed due to the COVID-19 crisis. They tends to ignore that the problems caused by the new geopolitical situation4 have also been part of the structural dynamics of the French economy in recent years. This explains, at least in part, the limited and incomplete nature of the answers that economists and officials intend to give to the problems facing the French economy. In a situation where production is partially limited by supply, the classical Keynesian answer, while necessary5, is insufficient. The inflation affecting the French economy, as well as all European Union economies, is a form of inflation caused by scarcity, rather than excess demand. Fighting this type of inflation requires a different type of policy than traditional monetary policy.

In a situation of uncertainty, it is also inappropriate to rely on the functioning of a market economy. Forms of planning along the lines of what was implemented in France from the late 1940s to the late 1960s would have been much more appropriate to the challenges facing the French economy.

Conditions for economic recovery after the recession caused by COVID-19

At the end of 2021, the French economy entered the path of a relatively rapid economic recovery after the recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic6. However, there are important questions that remain unresolved. Thus, GDP growth slowed markedly (-0.2% in Q1 2022 vs +0.5% in Q4 2021) due to falling domestic demand: household consumption declined sharply (-1.3% after +0.6%), investment growth, in other words, gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) declined slightly (+0.2% after +0.3%). Thus, final domestic demand, not tied to stocks, fell -0.5% in the first quarter of 2021 after a change of +0.4% in the previous quarter7. This posed a problem, as France was hit harder by the COVID-19 recession than many of its neighbors (Sapir, 2021). The semiannual results, while showing a slight improvement, did not allay concerns about growth. The latter recovered in the second quarter of 2022 (+0.5%), but the forecast, which seems optimistic to us, should slow to +0.2% in the third quarter and 0.0% in the fourth quarter8.

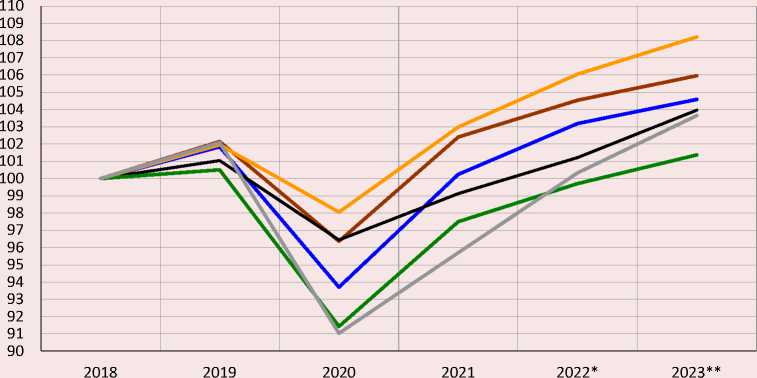

In 2020, France’s economy was much more shaken than that of some neighboring countries. The depression caused by complete and partial isolation in 2020 and early 2021 was stronger in France than in Germany, Belgium, or the Netherlands, but relatively weaker than in Spain and Italy (Fig. 1).

We should note that France lies between the countries hit hard by this depression, such as Italy and Spain, and the countries that are much less affected (Germany and the Netherlands). The measures taken by the government, in particular the “at all costs” principle, which favored mass support for workers, certainly made it possible for France to limit the negative impact of COVID-19 on the economy, but at a high cost to the state budget. Therefore, we should pay attention to two points:

– on the one hand, the total weight of debt in GDP is much higher than the EU average, even if it remains much lower than that of Italy;

– on the other hand, the support was provided mainly by non-monetary measures and not directly at the expense of the budget (Tab. 1) .

Figure 1. Development of Europe’s largest economies during the COVID-19 crisis, % (2018 – 100%)

^^^^^^^* Belgium ^^^^^^^е France ^^^^^^^е Germany ■ - Italy ^^^^^^^е Netherlands ^^^^^^^е Spain

Source: FMI, World Economic Outlook , April 2022.

* Forecasts

** Assessments

Table 1. Volume of state support in 2020, % of GDP

|

Fiscal measures |

Monetary measures |

Overall effect |

Fiscal measures, % of total |

|

|

EU |

3.8 |

6.8 |

10.6 |

35.9 |

|

France |

7.7 |

15.8 |

23.5 |

32.9 |

|

Germany |

11.0 |

27.8 |

38.9 |

28.4 |

|

Italy |

6.8 |

35.5 |

42.3 |

16.1 |

|

Spain |

4.1 |

14.4 |

18.6 |

22.2 |

|

Austria |

8.6 |

2.4 |

11.0 |

78.0 |

|

Belgium |

7.2 |

11.9 |

19.1 |

37.7 |

|

Finland |

3.0 |

7.0 |

10.0 |

29.9 |

|

Non EU |

||||

|

UK |

16.3 |

16.1 |

32.4 |

50.2 |

|

USA |

16.7 |

2.4 |

19.2 |

87.3 |

|

Source: IMF. |

||||

Table 2. Dynamics of expenses (broken down by quarter), %

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

||||||||||

|

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

|

|

GDP |

-5.7 |

-13.7 |

19.4 |

-1.4 |

0.2 |

1.0 |

3.2 |

0.4 |

-0.2 |

|||

|

Household consumption expenditures |

-5.5 |

-11.5 |

19.0 |

-5.6 |

0.2 |

1.2 |

5.8 |

0.3 |

-1.5 |

|||

|

Total government consumption |

-3.5 |

-11.7 |

18.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

3.3 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

|||

|

Source: INSEE. |

||||||||||||

The consequences of this mode of support became apparent in 2021 and early 2022. The indebtedness of small and medium-sized enterprises increased, which entailed new ways of support.

At the end of each period of self-isolation, especially in the third quarter of 2020, household consumption recovered. This was positively influenced by the economic measures taken by the government as part of the so-called “at all costs” policy (Tab. 2). At the end of 2021, the Minister of Public Accounts, working under the Minister of Finance, estimated the costs caused by COVID-19 at 170–200 billion euros9.

However, the decline in household consumption in the first quarter of 2022 (-1.5% after +0.3%) indicates an unsustainable recovery in activity. Gross disposable household income in current euros declined in the first quarter of 2022 (-0.5% after +1.9%). An analysis of the sources of household income shows that, in particular, social payments fell sharply in the first quarter of 2022 (-1.5% after +2.7%). This is the result of a mechanical leeway of “inflation compensation” payments to households at the end of 2021.

The decrease in consumption was partially offset by the January 2021 increase in basic pensions and a sharp increase in sick leave due to the Omicron variant. In addition, fiscal charges increased sharply (+3.6% after -0.5%).

Wage growth for household members slowed slightly (+1.0% after +1.3%): wage employment continued to increase (+0.3% after +0.4%), but average per capita wages declined slightly (+0.7% after +0.9%) due, in part, to an increase in sick leave10.

10 INSEE, Informations Rapide s, 137, 31 mai 2022.

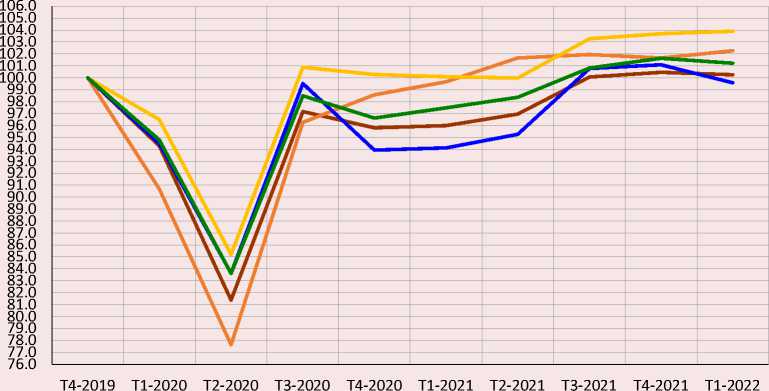

Thus, household consumption declined, especially for vehicles (-2.3% after -0.9%), other manufactured goods (-2.1% after -0.6%), and hotel and restaurant services (-3.9% after -0.9%). Consequently, household consumption in the first quarter of 2022 remained below the level it reached in the fourth quarter of 2019 (Fig. 2, Tab. 3) . If final domestic demand exceeds the level of the fourth quarter of 2019, it will be due to the measures taken to prevent consumption from declining too much from the fall of 2020 to early summer of 2021.

However, it should be noted that support measures did not cover part of the population, especially people with the lowest incomes and the self-employed (private entrepreneurs). Assistance was mainly provided to the employed population.

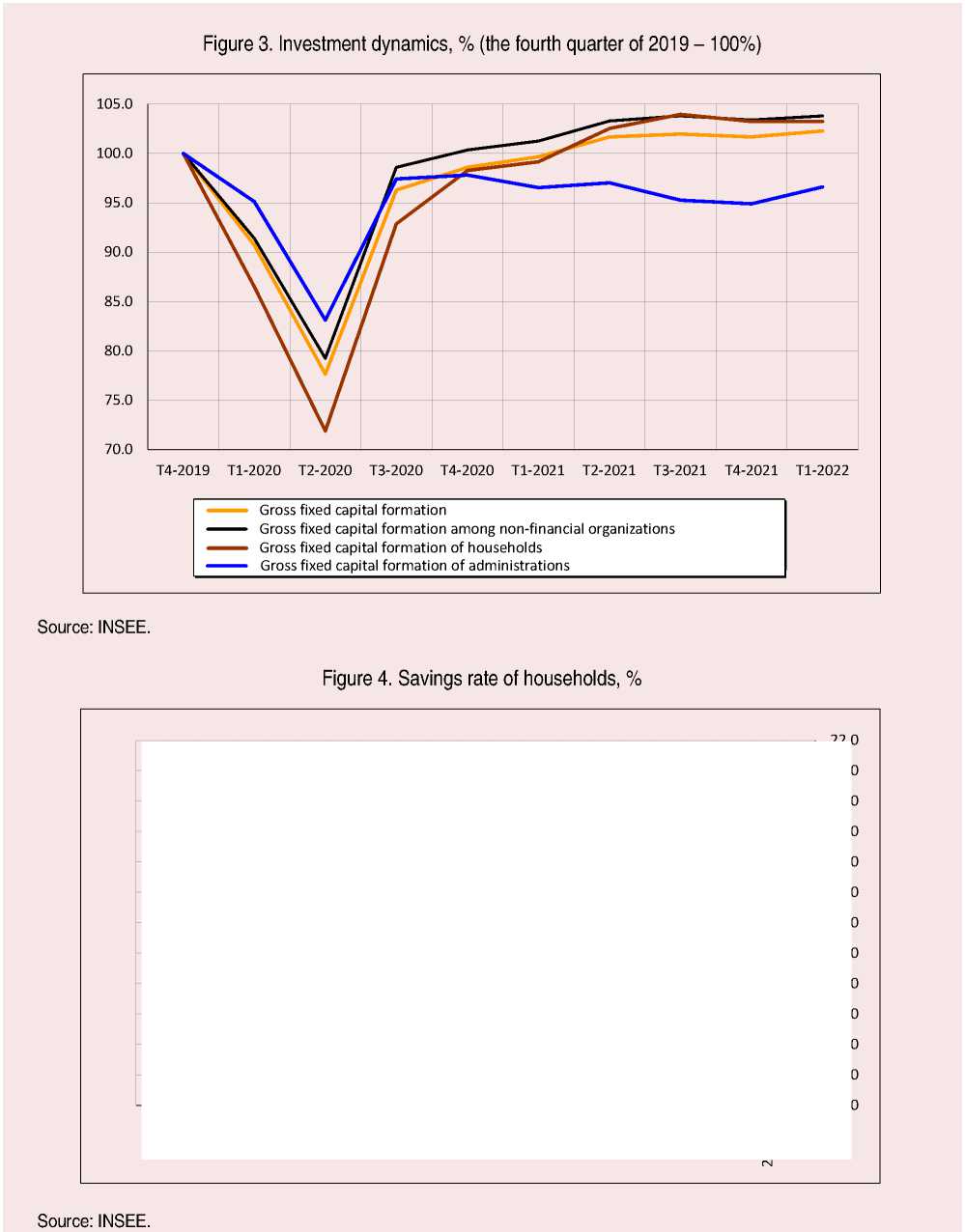

It is worth noting that the slowdown in the recovery of investment growth is associated with both a decline in public investment and stagnation since the third quarter of 2021 of investment by households and non-financial companies (Fig. 3) .

Figure 2. Macroeconomic indicators, % (the fourth quarter of 2019 – 100%)

^^^^^^^е GDP ^^^^^^^е Gross fixed capital formation ^^^^^^^е Household consumption ^^^^^^^е Administrative consumption ^^^^^^е Final domestic demand

Source: INSEE and CEMI.

Table 3. Final demand components dynamics (the fourth quarter of 2019 – 100%)

|

Q4 2019 |

Q1 2020 |

Q2 2020 |

Q3 2020 |

Q4 2020 |

Q1 2021 |

Q2 2021 |

Q3 2021 |

Q4 2021 |

Q1 2022 |

|

|

GDP |

100.0 |

94.3 |

81.4 |

97.2 |

95.8 |

96.0 |

97.0 |

100.1 |

100.5 |

100.3 |

|

Household consumption |

100.0 |

94.5 |

83.6 |

99.5 |

93.9 |

94.1 |

95.3 |

100.8 |

101.1 |

99.6 |

|

Administrative consumption |

100.0 |

96.5 |

85.2 |

100.9 |

100.3 |

100.1 |

100.0 |

103.3 |

103.7 |

103.9 |

|

Final domestic demand |

100.0 |

94.8 |

83.6 |

98.5 |

96.6 |

97.5 |

98.4 |

100.8 |

101.6 |

101.2 |

|

Source: INSEE. |

||||||||||

Nevertheless, household savings increased dramatically during the quarantine in 2020 and early 2021. Most of the middle and upper middle class saved what they could no longer consume. Therefore, one would think that we faced a conjunctural phenomenon.

However, events in 2021 show that while the savings rate will decline slightly, it will not return to 2018–2019 levels (Fig. 4) . Thus, the health care crisis seems to have served as a warning of global uncertainty. Thus, households faced with this uncertainty tend to increase their savings.

It should be noted that this applies only to the population from the fourth decile. The first deciles, that is, the population with the lowest incomes, actually lost their savings due to the health care crisis. Thus, the crisis led to an increase in income inequality.

The savings accumulated by part of the population remain largely passive. One reason for this situation is that the expectations of both entrepreneurs and households about the prospects of the French economy are not conducive to investment. We should also note that companies, whose debt levels have risen sharply because of the health care crisis, prefer to use their resources to reduce debt for fear of a significant increase in interest rates.

Weak investments by households and businesses could (and should) have been compensated by public investments. But the state is in the grip of a significant increase in social spending (due to the COVID-19 crisis and the need to protect the population from rising prices, which began to be felt in the summer of 2021) and the fear of not being able to service the sharply increased public debt.

Source: INSEE.

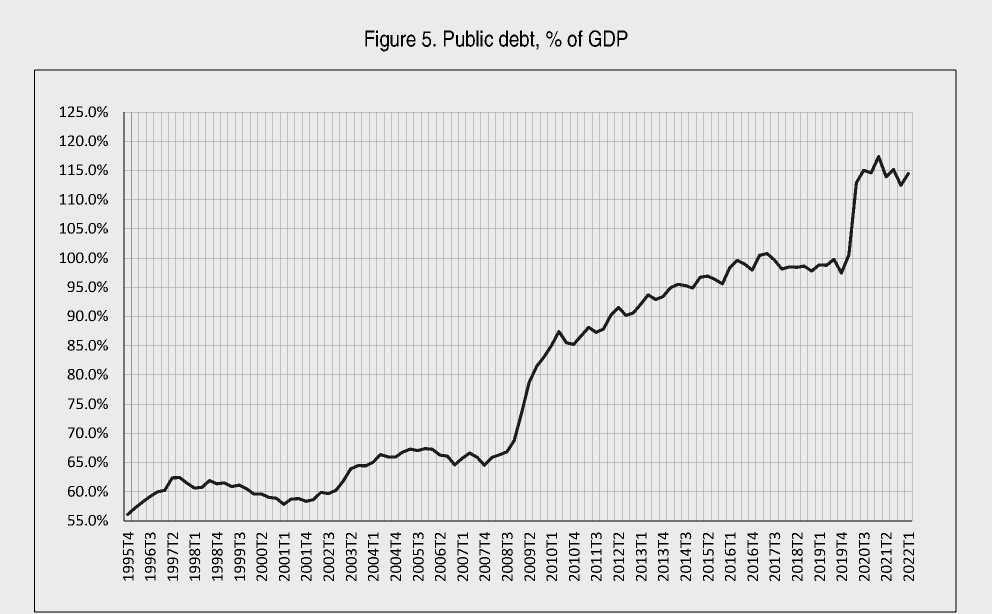

In fact, the national debt, which reached 114.5% of GDP in the first quarter of 2022, has increased in two stages since 2000. Figure 5 reflects that its increase is on a “ladder during crises”, whether it is the financial crisis of 2008–2010 or the COVID-19 crisis. Such increases are normal. The stages of debt growth correspond to periods of implementation of fiscal policies aimed at limiting the impact of these crises. However, we also see that it increased slowly but surely between 2010 and 2019.

Concerns about debt service (or its cost) arise because the European Central Bank, like other international central banks, raises key rates. Nevertheless, this could be expected from late 2020 or even early 2021. In this context, the French government has seen no other option than to keep social spending high and limit public investment, while demand is very high. Thus, this political choice is combined with “austerity” reflexes, resulting in a relatively low level of public investment, which has been holding back GDP growth since the third quarter of 2021.

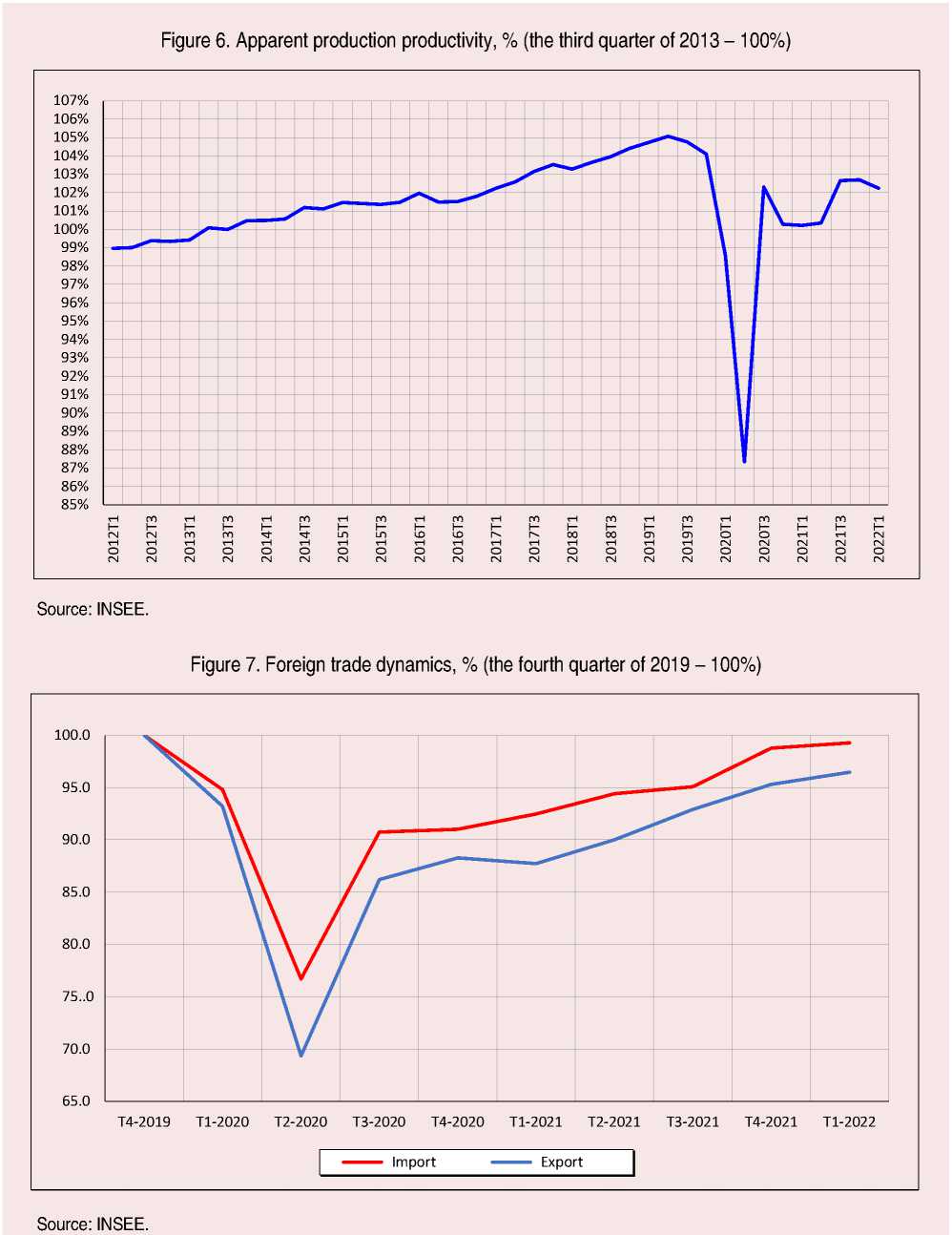

With the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, labor productivity began to decline. There are many explanations for this decline, which has led to an increase in wage employment as production struggles to return to 2019 levels.

To some extent, it was influenced by the health measures adopted by companies. In particular, the mass shift to telecommuting in the spring of 2020, which was welcomed by company leaders, turned out to be negative in terms of working conditions over time (there were risks of employees working remotely more than two days a week) and had a detrimental effect on productivity.

We should also note that measures to support employees and companies have led to the preservation of a certain number of organizations that would normally have to disappear. They are called “zombie companies”11.

In addition, labor market imbalances associated with shortcomings in vocational training and skewed wage structures that rendered various productivity measures ineffective may have led to a situation in which productivity fell. Also, the supply disruptions that have characterized the French economy since late spring 2021 have certainly contributed to its decline. Overall, wages, employment, and productivity indicators have not returned to the level of 201912.

However, while the decline in productivity has a favorable effect on the unemployment situation, it affects the macroeconomic situation in two ways:

– contributes to an overall increase in prices;

– leads to a greater deterioration in the balance of trade than competitors.

This is confirmed by statistical data.

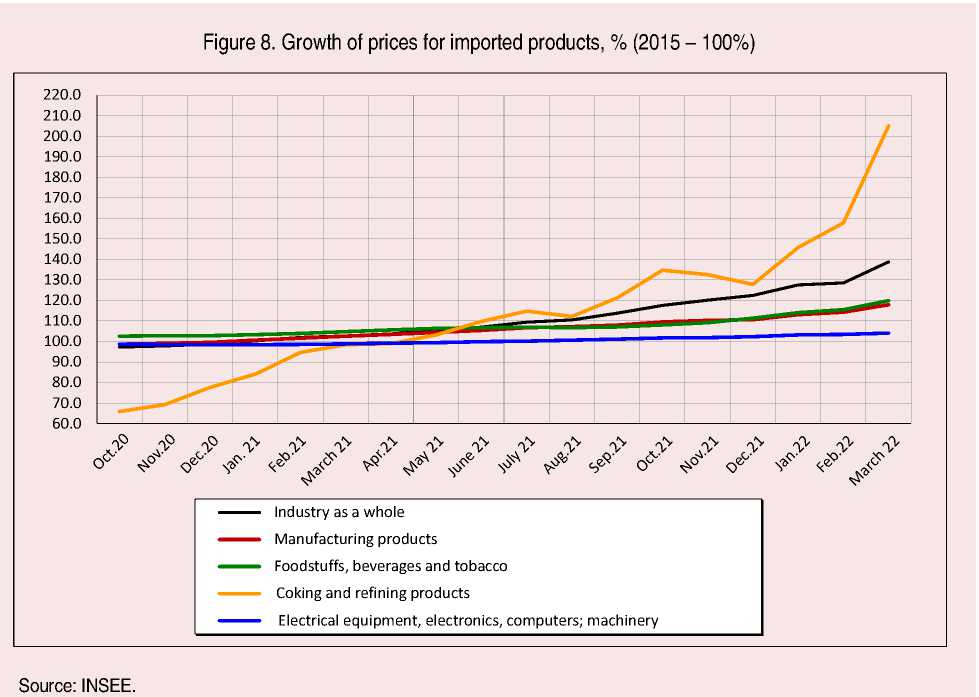

Indeed, one of the consequences of the COVID-19 crisis in France has been a greater reduction in exports than in imports. This can be understood when one considers that many businesses have had to suspend operations because of the quarantine and that the global demand for goods produced by French industry (in particular transport equipment) has dropped significantly. However, we see that the gap compared to the situation in 2019 persists in 2021, during the gradual recovery of the global economy from the crisis caused by COVID-19 (Fig. 6, 7) .

Undoubtedly, the competitiveness of the French economy has deteriorated sharply due to the health care crisis. This could affect the competitiveness of the economy in the future and also creates risks of inflationary tensions.

We should note the following regarding the above:

-

• France’s economy has not recovered despite the government’s considerable financial efforts during the crisis; after the rebound at the end of 2020, it remains in a phase of weak growth;

-

• foreign trade performance is below the 2018–2019 level, but the trade deficit tends to increase significantly, indicating a sharp deterioration in the country’s competitiveness;

-

• since June 2021, the manufacturing industry has been stagnating, while the “automotive” and “transport equipment” sectors have recorded a drop in production volumes, which clearly indicates the continuation of the cycle of deindustrialization.

The problems of “deficit” inflation in France

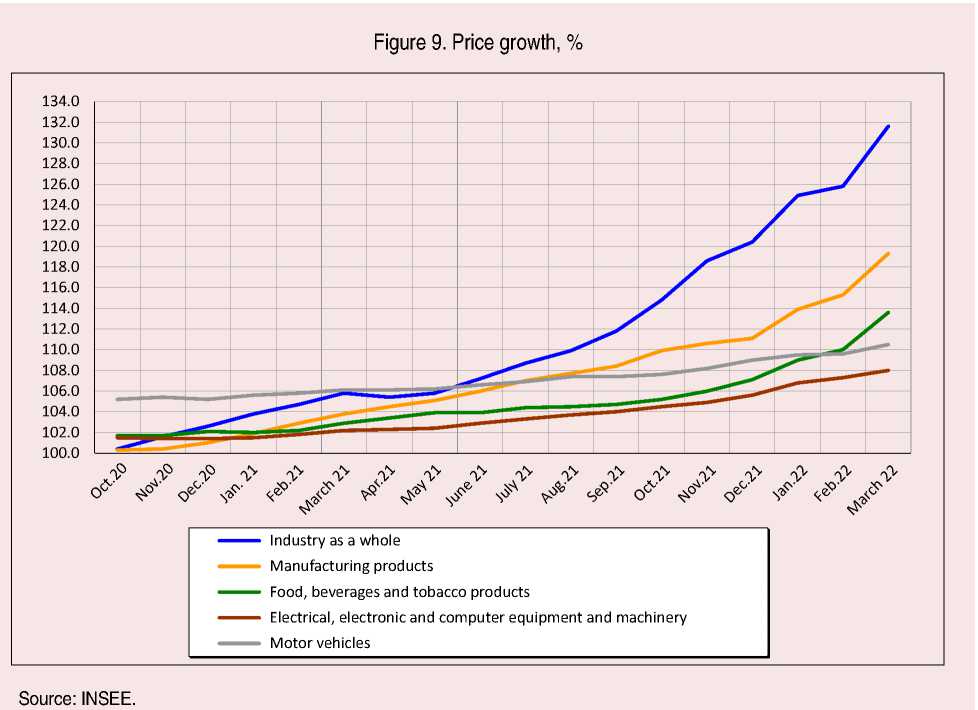

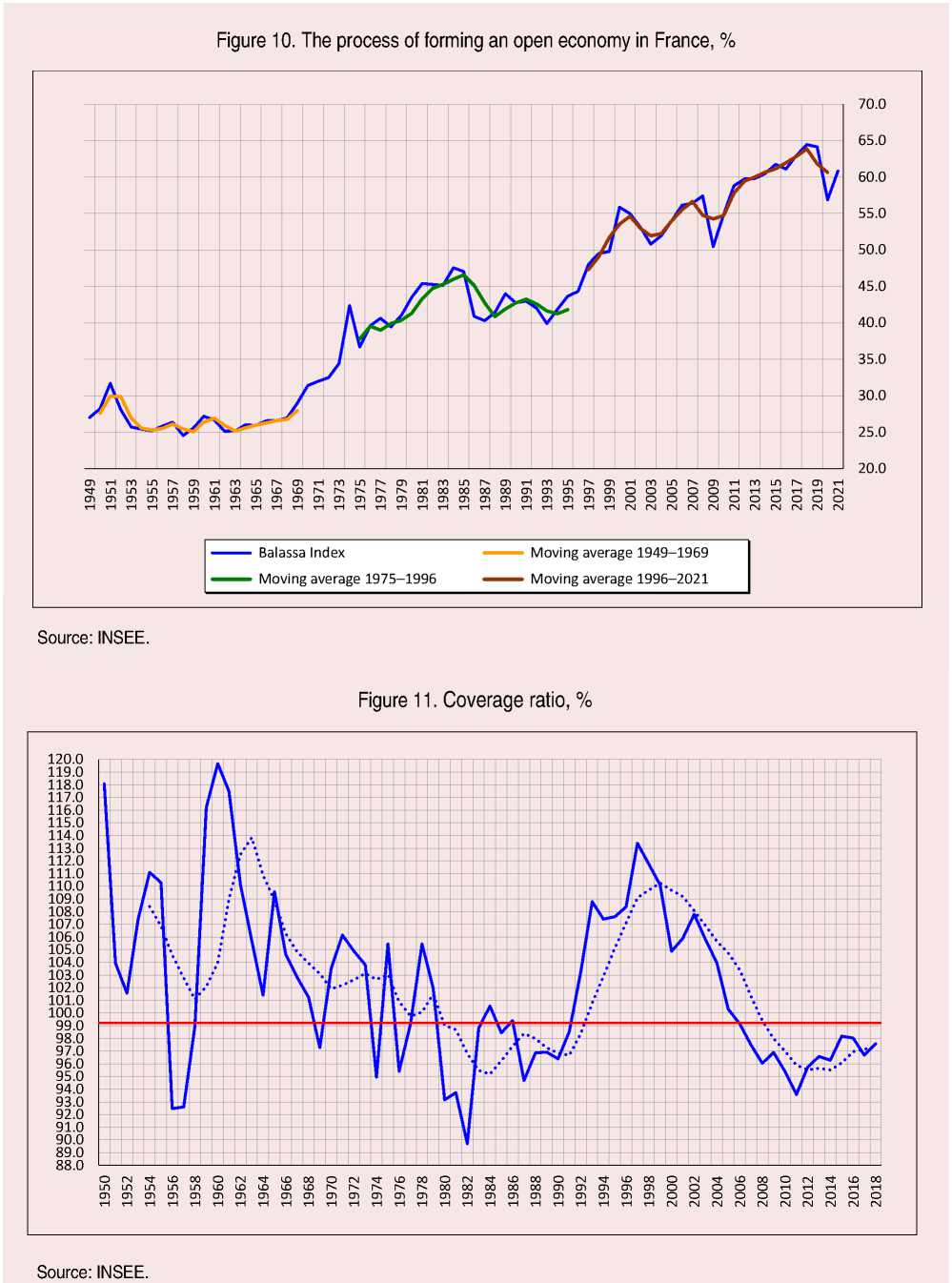

Inflation has been a serious problem for the French economy since the beginning of fall 2021. This is reflected in the rise in prices of some crucial commodities (fuel, microprocessors as well as food), which, in addition to their direct impact on the economy, lead to an increase in the prices of other products13. Thus, this is inflation of a special type, which is not due to excessive demand, but to a shortage of supply caused by certain conditions. The monetary dimension of this inflation seems weak. The French economy, like all European economies, actually faces a large change in relative prices, which requires specific measures (Aoki, 2001). Such inflation can spread because of the rigidities that exist in the production process and the

inability to replace, at least in the short to medium term, certain products (Greenwald, Stiglitz, 1989; Stiglitz, 1989).

The turning point actually came at the end of spring 2021. It was then that it became possible to measure the gap between the recovery of demand, which was gradually returning to normal levels, and the difficulties of resuming supply. The latter was hampered by the long-term effects of COVID-19 in the manufacturing sectors (relatively slow resumption of certain activities), as well as in the transport and logistics sectors.

This explains why inflation was first felt at the level of imported products (Fig. 8). Then it gradually affected various industrial sectors in France, because of rising costs or a shortage of certain resources. This upturn gradually took on the features of a domestic upturn. To it is added the growth caused by the contradiction between savings and investment. Thus, inflation is not the result of the situation in Ukraine or the Chinese isolation (although they have undoubtedly worsened the situation).

Over the year, according to INSEE’s preliminary estimate, consumer prices will rise 5.8% in June 2022 after rising 5.2% in May 2022 and +4.8% in April. The price increases are due to three main reasons: accelerating energy price increases, rising food prices, and increases in manufactured goods. However, the growth is uneven.

While consumer prices rose 0.6% for the month, compared to +0.4% in April, the difference is not significant. Energy prices are recovering along with the rise in prices for petroleum products, but, according to INSEE, the rise in food prices will be less noticeable than in April. Prices of services and manufactured goods will decline (Fig. 9) .

Consequently, the price increase largely depends on the disruptions in production and logistics caused by the crisis related to the spread of COVID-19. It is not directly related to the situation in Ukraine. But, obviously, it can only accelerate the price increase. In the case of France, this is exacerbated by a decline in productivity, which has some inflationary consequences.

Price increases are mainly due to disruptions in the production process and supply chain. As mentioned above, the increase in product prices is mainly due to higher costs14. But it is important to remember that inflation always causes significant shifts of wealth in the economy (Varoudakis, 1995). This affects businesses differently. Small and medium-sized enterprises suffer more than large and very large ones, which has much to do with the ability of large companies to negotiate certain prices. Thus, the effect on the margin rate may be different depending on the size of companies. It is also obvious that the dynamics of this phenomenon will not be the same depending on the sectors of activity. Therefore, the specifics of each sector should be taken into account when setting prices (Mankyw, Reis, 2002). This conclusion then opens up a research agenda that differs from the standard one, emphasizes demand imbalances, and may be close to the research agenda of economists representing the French school of regulation, in particular because of the importance given to the notion of a production system composed of heterogeneous sectors (Aglietta, 1976; Boyer and Mistral, 1983; Mazier et al., 1984).

We should note that Germany seems to suffer from this phenomenon more than France because of its greater dependence on energy imports.

The decline in labor productivity, which we have already mentioned, also plays its part. From this point of view, given the size of its fall after the

COVID-19 crisis, it is not surprising that there is a sharp rise in prices.

In general, non-monetary inflation is clearly visible (Sapir, 2010). Today, the question of its sustainability is raised15.

Finally, it should be noted that price increases cannot be perceived equally by the population. Lifestyles are highly correlated with income levels, and the housing issue, including transportation costs, will determine how price increases will affect different segments of the population.

The fact that the main increase in prices is in energy and food indicates that the part of the population living outside of major metropolitan areas and having a low level of income (with a high share of food consumption) will be significantly more affected by this upward movement.

The impact of rising prices on the income balance of a great part of the population, that is, on what is left over for the household after basic expenses, is significant.

Thus, we can see that the upsurge in inflation will certainly continue, as its causes remain or even worsen due to the situation in Ukraine, the imposition of sanctions and counter-sanctions.

The monetary policy measures that the Central Bank plans to adopt will have little effect. Demand is not excessive, but external factors prevent the growth of supply.

What is important, however, is that inflation, which has been absent for almost thirty years, has returned as a main economic problem. It is also possible that in 2023 there will be another inflation, this time related to distributional problems. Inflation exacerbates social disparities, so it is urgent to recreate the “Conference on price and income policies” which operated in France from 1948 until the end of the 1960s.

Exacerbation of the problems of the French economy in the context of the situation in Ukraine

The situation in Ukraine, which has created a context with the different waves of sanctions adopted by the European Union and Russia’s counter-sanctions, undermines international trade. This will inevitably have painful consequences for the French economy due to the impact of rising energy prices and possible energy shortages by the winter of 2022/2023, as well as the supply chain problem.

The dependence of the French economy on international trade is a serious problem. It is clear that playing the market alone will not solve it and a corresponding and active economic policy will be necessary. But the latter is still unlikely for political reasons.

The situation with Ukraine, through the mechanisms of sanctions and counter-sanctions, will have serious consequences for the French economy. Despite the fact that France is less dependent on hydrocarbon supplies from Russia than other European countries, the overall increase in energy prices will have a significant impact on it. The rise in energy prices will continue even if, due to a possible regional recession in Europe, it stabilizes over the summer. Sharp increases in energy prices are expected next winter16.

Note that the forecasts (Tab. 4) were made in June 2022. Since then, the oil and gas supply situation has further deteriorated. Thus, we can consider these forecasts to be very optimistic about the situation this winter and in 2023. Public debt is likely to exceed 112% of GDP and could reach 120% due to budgetary measures taken to compensate for the increase in the price of fuel. As for GDP growth, a recession forecast of about -1% does not seem realistic at present. If Germany’s recession is -3.0 to -4%17, then France’s is at least -2% or worse.

There is also the question of refined products (diesel) and products derived from hydrocarbons (fertilizers). The French economy depends relatively weakly on imports of Russian oil, but most of the consumed diesel fuel is bought in Russia. The share of fertilizers bought directly or indirectly from Russia is also significant, so the price increase will have an impact on agriculture in France.

In addition to the impact on industrial production and transportation services, there will be an impact on household consumption. The consequences of rising prices and shortages of certain goods could have a significant impact on economic growth in 2022 and 2023. However, this problem does not only affect France. In Germany, for example, growth may be only 1.7% instead of

Table 4. Comparison of the main scenario and the unfavorable scenario

Main scenario Unfavorable scenario 2022 2023 2024 2022 2023 2024 GDP +2.3% +1.2 +1.7% +1.5% -1.3% +1.3% Price index 5.6% 3.4% 1.9% 6.1% 7.0% 0.7% Public debt (% of GDP) 112 109 109 113 114 117 Source: Banque de France, Projections Macroeconomiques, June 21,2022. Available at:

-

4.5% in 2022, and the recession will begin in 2023.

Given the high degree of uncertainty in the current situation, forecasters at the Bank of France have developed an unfavorable scenario for the economy in which additional risks materialize, including much more pronounced tensions over energy and food prices. The unfavorable scenario should be interpreted as a risk in relation to the main scenario, which at this stage is still considered the most probable. Under the unfavorable scenario, economic growth will slow significantly in 2022, GDP will decline by -1.3% in 2023, and will partially recover (to +1.3%) in 2024. Rising commodity prices will lead to inflation above 6% in 2022 (INSEE predicts 7% growth) and 2023, followed by a more pronounced decline in 2024.

Public debt would rise sharply in this scenario, even with unchanged fiscal policy. It should be noted that the projections do not include all the potential effects of a “second round” caused by the start of the recession in countries such as Germany, Italy, or Spain.

The total losses related to the situation in Ukraine, primarily due to the imposition of sanctions and counter-sanctions, for the French economy would amount to about 2 points of GDP over the period 2022–2024.

France’s dependence on imports makes it particularly vulnerable to future shocks. This was already noticed during the COVID-19 crisis.

The aftermath of the situation in Ukraine has exacerbated pre-existing supply tensions resulting from the COVID-19 crisis. These tensions have fueled high inflation through the significant contribution of energy prices tied to the price of oil. In addition, the price of refined diesel, which has already been increasing for 2021 during the recovery from the coronavirus pandemic, has risen sharply since February 2022. Indeed, the conflict in Ukraine has led to a significant reduction in

Russian diesel exports (France imports about 20% of its diesel from Russia), which has contributed to higher refining margins and is ultimately reflected in gas station prices.

The openness of the French economy (Fig. 10) has led to a dependence on shocks caused by the global economy. This situation is not unique to France18. While greater openness has contributed to faster economic growth, it has certainly increased susceptibility to external shocks.

The French economy opened up gradually, in three stages. The first one is associated with the entry into force of the EEC (the forerunner of the EU) from 1965 to 1975. The second corresponds to the period of so-called “globalization”, the last years of the GATT and the introduction of the WTO (from 1991 to 2000). The third stage lasted from 2010 to 2019. It is worth examining the reasons for the third wave, as the situation in France at that time differed from that of other countries, whose Balassa index, by contrast, had fallen since 2012. In the case of France, the third wave also corresponds to the fall of the EU rate, which covers imports at the expense of exports, and the trend toward a worsening trade deficit.

Today, this openness of the economy in France has visibly transformed into dependence, as reflected in Figure 11. The deterioration of the coverage ratio appears to be structural and more prolonged than in previous episodes of deterioration.

With the continuation of the crisis and the imposition of sanctions and counter-sanctions, we should expect an increase in prices for all imported industrial resources, and the increase in tariffs, as already noted, will affect all types of production.

Substitution policy is possible, but its implementation will be costly and labor-intensive. The willingness to move some types of production within the country will certainly take time. Thus, the excessive dependence of the French economy on international trade is a central issue today.

The growing trade deficit is now a serious problem. France’s foreign trade performance has deteriorated, both because French industry products (aircraft construction) have been less in demand on the international market, and because of the limited specialization of the French economy19.

This brings us back to the problem of selfsufficiency, which was already raised during the COVID-19 crisis. In this regard, we should recall the President’s statement at the opening of the exhibition “Made in France” on July 2, 2021: “what is made in France is sovereignty, independence, that is, the ability, as many of you have done, to transfer know-how or part of production to French land” 20. In his speech delivered on June 29 on the occasion of the presentation of the 2030 health care innovation strategy, the word “sovereignty” was mentioned four times21. It was also present in an address to the French people on November 24, 202022.

On October 12, 2020, Emmanuel Macron named a number of challenges facing France23. He recognizes the phenomenon of strong dependence: “The second is our dependence on foreign countries.

We wanted to forget about it because we were living in a miracle, but we were a little oblivious then to its fragility (...) I haven’t forgotten that 18 months ago we were all short on masks. No one thought we could run out of masks, it was one of the things that had the least added value. In addition, we used them collectively, indirectly, because it was never the supposed choice of the nation, we delegated the production of masks to countries that produced them at a much lower cost than we did, saying, “Never mind, there will always be masks. Experiencing dependence can be dramatic. When there is an dependence and we find ourselves in situations where there is no more cooperation, that is the drama. And so we can no longer think of our economy, our production systems, as if everything is set up in such a way that everything will go well under any circumstances” 24. Two words are important here, because they are very revealing.

First, the word “miracle” used to describe the situation of globalization. Second, “cooperation”. Macron apparently ignores the fact that cooperation is never the only norm, but accompanies conflict. It follows from the last sentences of the quotation that he perceived cooperation as the eternal norm and was very surprised to find that it was not. In addition, we assume that he saw the world as a structure in which radical uncertainty and conflict were excluded.

First, however, the question of the main directions of economic policy has to be decided. Indeed, the way out of a situation of dependence cannot be predetermined.

Market mechanisms are not capable of overcoming these problems on their own. Clearly, important government decisions are needed, reflected in fiscal and monetary as well as structural policies. In the case of France, it is clear that the shock of the health crisis played a major role, exposing in particular the pre-existing problem of deindustrialization of the country. The result was the return of the idea of the Plan to the public debate.

The idea of a “plan” for what has been done in the past is now becoming a necessity. Emmanuel Macron and his government seem to have taken measures to slowdown the French economy. One of his first reactions was to recreate the High Commissioner’s plan in September 2020. One year later, on October 12, 2021, he submitted a draft plan for 2030. However, Paragraph 1 of Decree °2020-1101, reinstating the General Planning Commission (GPC), provides the following: “There is hereby established a High Commissioner of Planning, responsible for directing and coordinating the planning and foresight work conducted on behalf of the State, and for explaining the choices of State agencies with respect to demographic, economic, social, environmental, health, technological, and cultural issues”. The functions of the GPC are at the level of prospective, useful and necessary tasks, but that is not what such an organism requires. The GPC is more concerned with coordinating the activities of various forecasting bodies, such as France-Strategie, than with its function, which should be to identify development priorities and their implementation, to maintain a constant dialogue with administrations and enterprises, and to plan ways to achieve the goals set.

The effects of the 2008–2010 financial crisis on the French economy

We can consider that the French economy has not yet solved the structural problems revealed by the financial crisis of 2008–2010, also known as the “subprime lending” crisis. This has been masked by exogenous shocks, but is in fact a “background” on which the effects of external shocks are superimposed. The persistence of these problems explains the very fragile situation we were in before the COVID-19 crisis. Undoubtedly, the latter led to specific problems, then amplified by the international context, and these problems have become so important only because the French economy has not overcome the effects of the previous financial crisis and has not learned its lessons.

The phenomenon of mass unemployment has been around for a long time, and we must question the current government’s claim that it is in a state of regression and that “full employment” will be achieved25.

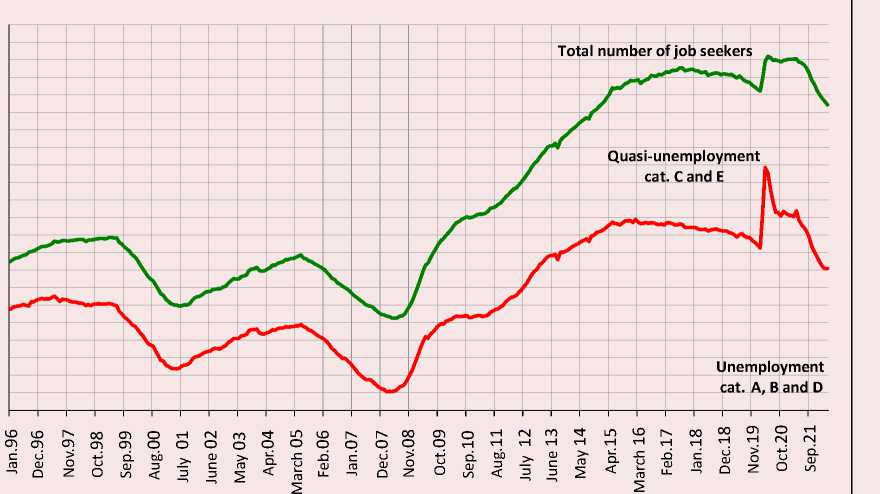

Indeed, for many years the government considered only those whom the DARES (Pole-Emploi) classifies as “category A”, that is, the unemployed who are actively looking for work, to be unemployed. However, it is more fair to consider also categories “B” and “D”, that is, part-time workers (B) and those who are unemployed but administratively exempt from “active search” (D). All three categories together (A + B + D) represent the actual number of unemployed. At the moment this group of people is numerous and amounts to more than 4 million people, although it has decreased slightly since January 2021 (Fig. 12) .

In fact, this figure is 13.7% of the active population in France (including the unemployed), not 7.2%, as stated in the data provided by the government. To this should be added people with involuntary part-time jobs (who would like to work more) and those in subsidized jobs, i.e. jobs that are directly dependent on the social policies of the state. This group, which corresponds to categories “C” and “E” in the DARES system, now numbers 2 million people. It has increased dramatically over time, as it included only 800,000 people on the eve of the 2008 crisis. Thus, a total of 6 million people, or 20% of the economically active population, are unemployed or without employment security.

6 800,0

6 600,0

6 400,0

6 200,0

6 000,0

5 800,0

5 600,0

5 400,0

5 200,0

5 000,0

4 800,0

4 600,0

4 400,0

4 200,0

4 000,0

3 800,0

3 600,0

3 400,0

3 200,0

3 000,0

2 800,0

2 600,0

2 400,0

Figure 12. Demand for work in France, thousand people

Source: DARES/INSEE.

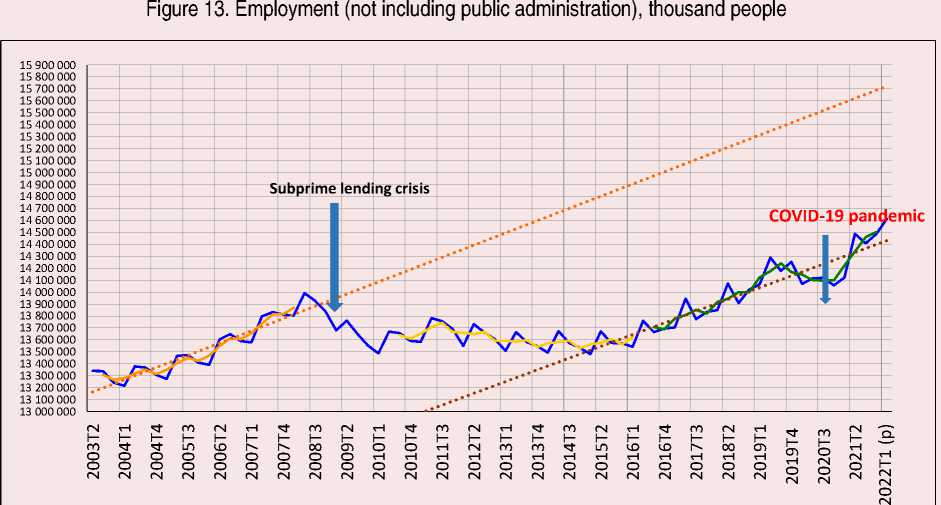

All sectors (excluding public administration) Moving average after the crisis 2010–2016 Linear (moving average 2003–2008)

Moving average 2003–2008

Moving average 2016–2021

Linear (moving average 2016–2021)

Source: INSEE.

It should be noted that the creation of “microentrepreneur” status for some 780,000 people also helped to mask unemployment.

In fact, the effects of the financial crisis of 2008–2010 have not been smoothed out or overcome. It undermined the dynamism of the French economy, and it has not yet recovered. If we look at total employment of wage workers, excluding public administration and self-employment (Fig. 13) , we see that compared to the pre-crisis period, the shortage is about 1.3 million workers, or 9% of the total. This demonstrates the magnitude of the problems facing the French economy today.

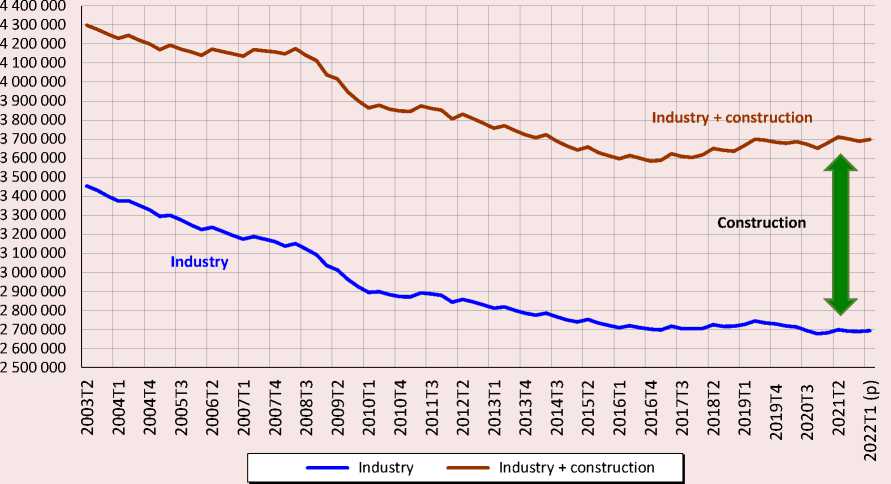

Nevertheless, an analysis of total wage employment, however eloquent its results, conceals another phenomenon: deindustrialization, which France has been experiencing for years. The absolute number of people employed in industry declined steadily from 2003 to 2015 (Fig. 14). In the period from 2015 to 2021, its level remained unchanged, but the number of employed people increased. To some extent, this was influenced by the growth of labor productivity.

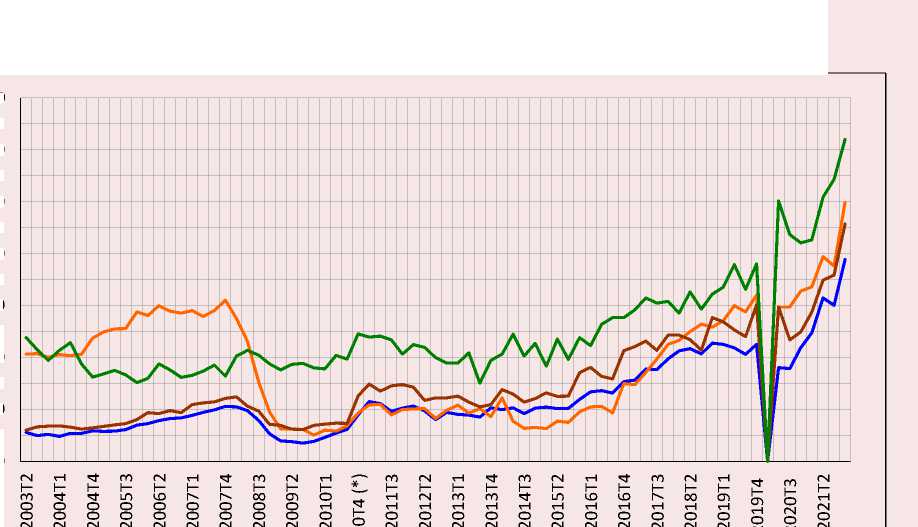

However, there has been an increase in the number of unsatisfied job applications in all industries (Fig. 15). In fact, this phenomenon has existed for quite a long time, but has acquired a new dimension due to the crisis caused by COVID-19. In fact, this growth reflects both disparities in the labor market and the corresponding attractiveness (or unattractiveness) of various sectors of activity. The fact that the percentage of unsatisfied applications is skyrocketing in the non-trade services sector is largely indicative of the mismatch between wages and expectations of potential workers in that sector.

Figure 14. Industry and construction employment (including government agencies), people

Source: INSEE.

Figure 15. Unsatisfied applications for employment, % of those employed in the industry

3.50

3.25

3.00

2.75

2.50

2.25

2.00

1.75

1.50

1.25

1.00

0.75

0.50

0.25

0.00

Industry

Construction

Tertiary sector (trade)

Tertiary sector (excluding trade)

Source: DARES/INSEE.

Conclusion

Thus, the situation characteristic of the French economy at the end of the first half of 2022 does not inspire optimism. A significant deterioration of activity is expected from the fall or winter of 2022. The combination of high inflation, a significant decline in business activity and the severity of the unintended consequences of the 2008–2010 crisis pose challenges for the government. Three conclusions emerge from the overview of the French economy that we have presented.

-

1. The French economy will face the consequences of the international situation related to the situation in Ukraine and the imposition of sanctions and counter-sanctions, in a state of double weakness due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the crisis of 2008–2010, the effects of which have not been fully overcome. Lack of investment, which affects key infrastructure in the country, such as in the energy

sector, will exacerbate the effects of reduced gas supplies as a result of sanctions26. This weakening will have a significant impact on the economy in the coming months. Moreover, faced with inflation and its impact on people’s most modest incomes, the Governor of the Bank of France, Mr. Francois Villrois de Galleau, warned the head of state of the “significant budgetary costs” of the announced anti-inflationary measures. According to him, these measures should be as long and targeted as possible27. Under such conditions, social tensions are likely to rise in the winter of 2022–2023.

-

2. Forecasts in recent weeks indicate a worsening of the situation (recession/preservation of high inflation). It should be noted that in the forecasts made by various organizations (Tresor, INSEE, Banque de France), the next year and a half to two years appear much more bleak than could have been assumed in March or April of last year. The awareness of the seriousness of the current situation is gradually growing. The risk of a major recession in the major EU countries can no longer be ruled out. This would directly or indirectly lead to a further deterioration of the French economy.

-

3. In order to cope with the new situation, an inflow of investment, both public and private, is

necessary. The issue related to investment now seems to be crucial for the ability of the French economy to overcome the difficulties caused by the international situation. In addition to raising again the issue of public investment, which unfortunately has received little attention since the beginning of 2021, private investment, especially investment in production, should be favored as the key to restoring productivity growth. However, given the uncertainty caused by the state of the French economy and the international economic situation, it is to be feared that private productive investment will remain low in the coming months. Thus, renewal policies must be implemented with stakeholder coordination.

Список литературы The French economy between the COVID-19 pandemic and a new geopolitical situation: relapsing into the crisis or overcoming it?

- Aglietta M. (1976). Régulation et Crises du Capitalisme. Paris: Camann-Levy.

- Aoki K. (2001). Optimal monetary policy responses to relative-price changes. Journal of Monetary Economics, 48(1), 55–80.

- Boyer R., Mistral J. (1983). Accumulation, Inflation et Crises. 2è ed. Paris: PUF.

- Dauvin M., Sampognaro R. (2021). Le modèle « mixte”: un outil ’évaluation du choc de la Covid-19”. Revue de l’OFCE, 2(172), 219–241.

- Greenwald B.C., Stiglitz J.E. (1989). Toward a theory of rigidities. American Economic Review, 79(2).

- Mankyw N.-G., Reis R. (2002). What Measure of Inflation Should a Central Bank Target. Working Paper. Harvard University.

- Mazier J., Baslé M., Vidal J.-F. (1984). Quand les Crises Durent. Paris: Economica.

- Sapir J. (2009a). La mise en concurrence financière des territoires. La finance mondiale et les États. In: Colle D. (Ed.). D’un protectionnisme l’autre – La fin de la mondialisation? Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Sapir J. (2009b). The social roots of the financial crisis: Implications for Europe. In: Degryze C. (Ed.). Social Developments in the European Union: 2008. Bruxelles: ETUI.

- Sapir J. (2010). What should Russian monetary policy be? Post-Soviet Affairs, 26(4), 342–372.

- Sapir J. (2016). Global finance, national interests, and the model of development. In: Zapesotsky A.S. (Ed.). Contemporary Global Challenges and National Interest – The 16th International Likhachov Scientific Conference. Saint Petersburg.

- Sapir J. (2021). The economic shock of the health crisis in 2020: Comparing the scale of governments support. Studies on Russian Economic Development, 32(6), 579–592.

- Stiglitz J.E. (1989). Toward a general theory of wage and price rigidities and economic fluctuations. American Economic Review, 79.

- Streeck W. (2018). Du temps acheté. La crise sans cesse ajournée du capitalisme démocratique, Paris: Gallimard.

- Varoudakis A. (1995). Inflation, inégalités de répartition et croissance. Revue Economique, 46(3), 889–899.