The Impact and Effectiveness of the Syllable-based Reading Approach on Moroccan Pupils’ Reading Competency

Автор: Abdessamad Binaoui, Mohammed Moubtassime, Latifa Belfakir

Журнал: International Journal of Modern Education and Computer Science @ijmecs

Статья в выпуске: 2 vol.15, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Morocco has recently introduced the syllable-based reading approach (SbA) in Arabic and French Curricula. Thus, this study aimed at measuring the impact and effectiveness of said approach on Moroccan pupils’ Arabic reading competency as well as how teachers approach it based on the hermeneutic phenomenology theoretical framework. A quantitative survey questionnaire was distributed to 227 1st and 2nd grade teachers from all twelve regions of Morocco. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used to analyze data through descriptive statistics and statistical hypothesis testing. The results showed that most Moroccan teachers advocate the use of the SbA as it positively impacts Arabic reading competency. They have, also, pointed out that time and demanding lesson planning are some of the SbA’s drawbacks. Also, it was found that there are no differences in SbA’s teaching practices and perceptions between female and male teachers except for the practice of assigning reading homework as female teachers tend to assign more reading homework. The results of the study are of significant importance to the MENA region as it evaluates field work regarding SbA.

Syllable-based approach, reading competency, teachers’ perceptions, oracy, syllabary

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/15019110

IDR: 15019110 | DOI: 10.5815/ijmecs.2023.02.03

Текст статьи The Impact and Effectiveness of the Syllable-based Reading Approach on Moroccan Pupils’ Reading Competency

After scoring 358 points in relation to the 500-center point (the mean) of the measurement scale (scale= 300-700) in the latest Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), which is an is an international comparative assessment that measures student learning in reading conducted by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement every 5 years [1] , Moroccan policy makers were urged to take measures in order to enhance Moroccan students’ oracy. Indeed, the latest primary school curricula reform targeted reading and speaking competencies by introducing short-story telling and the syllabic reading method, also known as the syllable-based approach (SbA) or the syllabary, starting from the first grade in both Arabic and French subjects as well as coding starting from the 5th grade [14].

In fact, the syllabary method was not intended to replace the alphabetical system by hundreds of syllables but rather, as [2] argue, it is intended to “dissect the conceptual problems of alphabetic reading for the child, rather than presenting all of them together”. Ref.[2] also suggest that the fundamental conceptual problem in reading acquisition is psychoacoustic as “it has to do with awareness of phonological segmentation and has very little to do with the writing system itself, i.e., the visual input”.

To our best knowledge, no previous study has examined Moroccan teachers’ perceptions of the newly adopted reading method neither its impact on pupils’ Arabic language reading competency. As a result, it is imperative to fill this gap by involving the change makers themselves (i.e., teachers). Consequently, this study aims at investigating Moroccan teachers’ perceptions of the SbA effectiveness and their use of the same reading approach based on the hermeneutic phenomenology theory as a theoretical framework. This paper, aims, as a result, at answering the following questions:

(a) How do Moroccan teachers approach the syllable-based reading approach?

(b) Do Moroccan primary schools’ teachers perceive the syllable-based approach to be effective in teaching reading and what is their evaluation of students’ productivity during SbA sessions?

(c) To which extent does teachers’ teacher gender influence the syllabary perception and use by Moroccan teachers?

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Syllable-based Reading Approach.

The first question would enable us to examine the SbA use by Moroccan 1st and 2nd grade teachers versus the reasons why they would not use it (if applicable) as well as their familiarity with its concepts, lesson planning and its pedagogical tasks. The second question measures the method’s effectiveness and impact on reading ability by exploring the factors enhancing its use and its drawbacks. The third question examines variations between female and male teaching in using and perceiving the SbA. By answering these questions, the present study would open discussion about the effectiveness of the SbA in North Africa and the Arab world so as to recommend proceeding with its use or not. It would, also, serve as a reference for comparative studies across different countries and different languages. Furthermore, according to the latest reports, reading competency is an underachieved competency even after primary school conclusion, thus, research on the area of reading enhancement is of huge urgency. On another note, the main limitation of the study was relying on quantitative data mostly. Therefore, we did leave room for comments and added an “other answers” option open for answerers which yielded significant feedback as discussed below.

The Moroccan 1st grade Arabic language teachers’ guide [3] (henceforth, guide) defines the syllabic method as a method aiming at enhancing the learners’ ability to spell out and read words. It relies essentially on matching the spoken with the written in terms of vocal segments (sounds) and combining them to form words while building a phonological consciousness which, in turn, raises the awareness that words are formed of multiple syllables. The syllabic method, in the same context, relies on the syllable-grapheme matching which aims at enhancing fluency (effortless reading) and comprehension.

Historically, the syllabary method dates back to the Babylonians [2]. At least seven ancient societies independently invented syllabary notations, and there are some modern instances of particular interest is the invention of a syllabary by the Cherokee Indian, Sequoyah; see, e.g., Gelb, 1952 [2]. Walker (1969) reports that the Cherokee were 90% literate in their native language in the 1830's, using the Sequoyah syllabary, and that by the 1880's the Western Cherokee had a higher English literacy than the white populations of either Texas or Arkansas [2].

Ref. [2] argue that on the basis of research in speech perception, it is suggested that syllables are more natural units than phonemes because they are easily pronounceable in isolation and easy to recognize and blend. They suggested that the introduction to a syllabary will teach children the basic notion of sound-tracking uncontaminated by simultaneous introduction of the difficult and inaccessible phoneme unit. They came to the conclusion that children have little or no difficulty in comprehending the basic principles of logographic systems: they can readily grasp the idea that language can be represented by a sequence of written signs, if the signs correspond directly to meaning. Children, according to them, find it very hard to identify the appropriate visual-auditory correspondences (phoneme-to-grapheme), and combine units (blending) which they confound in phonics-oriented approaches. The article authors provided the following example in order to account for the difference between the syllables and phonemes in terms of difficulty:

If the child cannot become aware of the fact that “bid, bug, and banana” start with the same sound, then he cannot come to understand the relevance of the written symbol “b” in the orthography. But once he can agree that bad consists of the sounds “b, a, and d” the child has learned the critical factor in decoding writing.

In an experiment on patients with apraxia of speech (AOS), new treatment approaches were conducted by [4]. These treatments focused on finding out the speech units and structural properties involved in the error mechanism of patients with apraxia. They reviewed data from single-word production experiments and from analyses of spontaneous speech demonstrating an impact on (1) the degree of “over-learnedness” of syllables (syllable frequency), (2) the internal structure of syllables (syllable complexity), and (3) supra-syllabic, metrical aspects of utterances (word stress) on error production in AOS. This was followed by two experimental learning studies and a treatment study taking these results into consideration. They concluded through the first learning experiment that syllables are more natural units than segments in the treatment of severe AOS. Consequently, they recommend, at the end of the study, the use a treatment approach which relies formally on related training syllables in the reacquisition of complex target syllables. Similarly, [22] tried to determine whether persons with AOS are able to make the intended stress pattern identifiable and, if so, to determine which acoustic cues they use to avoid the ‘equal stress’ phenomenon. The study yielded that, for each parameter considered (duration, intensity, fundamental frequency), apraxic participants’ productions differed from those of controls to varying degrees depending on the task.

Another recent intervention conducted on German second graders who demonstrated difficulties in the recognition of written words by [5] showed “significant improvements in standardized measures of phonological recoding, direct word recognition, and text-based reading comprehension after the 24-session intervention”. Accordingly, a plethora of other intervention studies have been proved to be beneficial by repeated reading of frequent and infrequent syllables, and syllable segmentation on poor readers’ accuracy and fluency of word recognition in several orthographies such as in Dutch (Berends & Reitsma, 2006; Wentink, Van Bon, & Schreuder, 1997), Finnish (Heikkila, Aro, Narhi, & Westerholm, 2013; Huemer, Aro, Landerl, & Lyttinen, 2010), French (Ecalle, Magnan, & Calmus, 2009), and English (Bhattacharya & Ehri, 2004;

-

2.2. Modern Standard Arabic Language Syllabary.

-

2.3. Syllabary Method Lesson Plan in the Moroccan Context.

-

2.4. Lesson Plan in the One Letter-One Phase per Week Phase.

Phonological changes and processes are noticeable in continuous speech and apply to both consonants and vowels [14]. In Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), There are three dominant syllables: CV (consonant-vowel), CVC (consonantvowel-consonant) and CVV (consonant-vowel-vowel) and two syllables CVVC (consonant-vowel-vowel-consonant) and CVCC (consonant-vowel-consonant-consonant) that appear only in surface phonetic forms such as at pause or following other phonological processes [7]. On a basis of data of 100 000 syllables, the frequency of occurrence of CV, CVC and CVV are 49.7%, 23.9% and 17% respectively. If we consider conjunctive hamzas as full-fledged consonants then CVVC and CVCC syllables together barely account for 1% of the occurrences of all the syllables while consonant clusters are not permitted in syllable initial position as cited in [7]. Teaching the syllabary in the Moroccan context relies only on the CV, CVC, CVV syllables. Thus, in a word like “كبش” (i.e., sheep), the segmentation would look like كب/ش i.e., CVC/CV and the segmentation of the word وجد (find) would be و/ج/د i.e., CV/CV/CV.

Reading, according to the Moroccan 1st grade Arabic language teachers’ guide [3], is a complex process of thought. It includes reading written symbols (words and phrases) and inferring their meanings. Its skills’ set consists of understanding explicit and implicit meanings, deducting, enjoying, analyzing and exploiting the text and providing an opinion about it. The guide which was conceived in order to help Moroccan teachers implement the SbA with ease, divides the reading competency into five elements: (1) oral consciousness; (2) the alphabetic principle (matching soundstreams with letters); (3) fluency; (4) vocabulary; and (5) comprehension. In this respect, Moroccan pedagogues have divided reading sessions into two phases throughout the scholar year. The sounds-letters phase and the text readingreading difficulties phase. The former is, in turn, divided into two phases: (1) one letter-sound per week and (2) two letters-two sounds per week.

This phase introduces eight sounds-letters throughout two units (the scholar year comprises six units). Each soundletter is taught in a whole week while the fifth week is dedicated to the consolidation of the four sounds-letters. Table 1 sums up the daily lesson plan:

Table 1. Syllable-based approach lesson steps in the Moroccan context

|

Days |

Day 1 |

Day 2 |

Day 3 |

Day 4 |

Day 5 |

|

Sessions |

Session (1) Sound/letter presentation |

Session (2) Sound/letter with short vowels |

Session (3) Sound/letter with long vowels |

Session (4) Sound/letter with tanween (nunation) |

Session (5) Sound/letter Evaluation and consolidation |

|

Steps |

|

-Evaluation and Consolidation Homework |

Homework |

Homework |

|

The two letters-two sounds per week phase are managed with slightly the same steps as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Syllabary in the two letters per week phase

|

Days |

Day 1 |

Day 2 |

Day 3 |

Day 4 |

Day 5 |

|

Sessions |

Session (1) 1st Sound/letter presentation and with short vowels |

Session (2) 1st Sound/letter with long vowels and nunation |

Session (3) 2nd Sound/letter presentation and with short vowels |

Session (4) 2nd sound/letter with long vowels and nunation |

Session (5) Both sounds-letters evaluation and consolidation |

The last six weeks of the scholar year introduces 6 short prose texts in order to enhance fluency and remediate reading issues.

2.5. Total Physical Response Movements Used in Teaching MSA Syllables in the Moroccan Context.

3. Theoretical Framework

4. Method

4.1. Sampling4.2. Instrument

Table 3. Movements used in teaching Arabic through the syllable-based approach Ref. [3]

|

The index finger points upwards if the consonant is followed by a Fatha (a). |

|

|

The index finger is rotated if the consonant is followed by a damma (u). |

|

|

The index finger points downwards if the consonant is followed by a kasra (i). |

|

|

fl |

The whole fist is held upwards in the case of a bare consonant (sukūn). |

|

if Ji |

Both index fingers point upwards in the case of a consonant plus the long vowel alif (aː). |

|

Both index fingers point forward in the case of a consonant plus the long vowel wāw (uː, oː). |

|

|

Both index fingers point downwards in the case of a consonant plus the long vowel ya’ (iː, eː). |

|

|

& |

The thumb is held up if the word contains the targeted sound/letter. |

|

The thumb is held down if the word does not contain the targeted sound/letter. |

In addition to the movements laid out in Table 3, pupils are also encouraged to clap after each syllable in order to emphasize each segment separately. These sort of total physical response exercises have been proved to be effective as they engage both action and reflection on a syllable basis.

When trying to understand the perceptions and experiences of individuals, one of the interesting theories to rely on is the hermeneutic phenomenology (henceforth: HP). The term "hermeneutics" comes from the Greek verb hermeneuein which means "to interpret” [8]. Dilthey [8] the main exponent of the method, sees it as the process that allows disclosing the meanings of the things found in the person's consciousness and interpreting them through the word. He also states that the person's written texts, attitudes, actions and all kinds of expression lead us to discover the meanings. The experiences, compiled by the hermeneutic phenomenology and then translated into descriptions, will be effective to analyze the pedagogical aspects in which the educator must be deeply interested in the events that occur in the classroom and optimize the pedagogical practice. In practical terms, the theory is translated into three phases: (1) Previous Stage or Clarification of Budgets (CoB): the researcher asks himself/or herself about the study’s phenomenon as explained by Van Manen [8]. It is about establishing the budgets, hypotheses, preconceptions from which the researcher starts, and recognizing that they could intervene in the research. This will be done through answers to questions proposed about our attitudes, values, beliefs, feelings, conjectures, interest, etc., in relation to the research with the aim of avoiding their presence in the interpretation of experiences [8].

The second phase consists of collecting the Experience Lived. This is the descriptive phase as data are obtained here from the experience lived from numerous sources: accounts of personal experience, protocols of some teachers' experience, interviews, autobiographical accounts and observation-description of a documentary. Openness is given to research through the writing of anecdotes, a usual methodological tool in the HP Method. The third phase: which is reflecting on the Experience Lived - Structural Stage (SS) consists of making a more direct contact with the life experience. The aim is to grasp the meaning of the fact of being a teacher, mother or father, in order to be able to fully live the pedagogical life with the students [8]. The reliance on this theoretical framework appeared logical as the main purpose of the method was to capture teachers’ perceptions, experiences, and opinions. Therefore, a hermeneutical study was deemed appropriate.

In order exclude teachers who have not yet taught using the syllabary (since the syllabary was introduced in teaching Arabic in the Moroccan schools only since 2018), we have opted for purposive homogenous sampling which included only 1st and 2nd grade teachers as they are the ones concerned with the application of reading reform. In purposive sampling, the researcher decides what needs to be known and sets out to find people who can and are willing to provide the information by virtue of knowledge or experience [9]. “Participants in Homogenous Sampling would be similar in terms of ages, cultures, jobs or life experiences” [9].

A survey questionnaire gathering quantitative data was used to gather information from the participants. Survey questionnaire designers, according to [10], “aim to develop standardized questions and response options that are understood as intended by respondents and that produce comparable and meaningful responses”. They are, as well, costeffective and provide data in shorter periods of time. The surveys were administered to the chosen sample and two dimensions of teachers’ input were studied: perceptions and use (pedagogical practices) of the syllabary. The questionnaire was translated into Arabic since not all primary school teachers can speak English. It is also worth noting that a pilot administration of the survey questionnaire had been undertaken before administering the questionnaires for adjustment purposes.

The questionnaire was divided into three sections (excluding demographics). The first section is a yes/no question aiming at answering whether the respondent relies on the SbA or not. If they do, they are taken to a set of questions examining their use and later their perceptions (based on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” =1 to “strongly disagree” =5. If they do not rely on SbA, they are taken to the section examining the reasons behind their refusal to use the SbA (multiple checkboxes and “other” box). For validity and reliability purposes, the researchers made sure to administer the questionnaire to 1st and 2nd grade teachers only by sending the google form to school principals and asking them to forward the questionnaire to the targeted sample. Finally, the data was collected from all 12 regions of Morocco. Table 4 shows the Cronbach’s Alpha reliability score of the Likert scale used in this study:

Table 4. Cronbach’s Alpha reliability test of the questionnaire

|

Cronbach's Alpha |

N of Items |

|

.946 |

16 |

5. Results and Discussion

The analysis of data will be guided by the hermeneutic phenomenology theoretical framework. The first phase, as discussed above, is the clarification of budgets (researcher’s own thoughts about the phenomenon). We believe, through experience, that the syllabary is beneficial. It can help struggling readers enhance their fluency. It is, as well, fun and easy to use. However, we will make sure that our views of the phenomenon do not interfere with how we approach the study’s data in any possible way. Our expectations of the study outcomes consist of positive endorsement to the syllabary as we have been sensing from our fellow teachers long before the study took place.

-

5.1. Gender Distribution

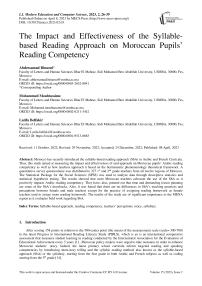

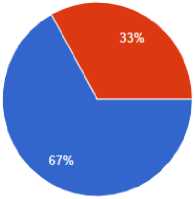

As can be seen in Fig. 1 and Table 5, male participants account for 41% while female participants account for the rest of the percentage. The difference in terms of gender is significant in this study.

Table 5. Participants by gender

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Female |

134 |

59.0 |

59.0 |

59.0 |

|

Male |

93 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

227 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

||

Gender 227 responses

Fig. 1. Participants by gender

-

5.2. Age Distribution

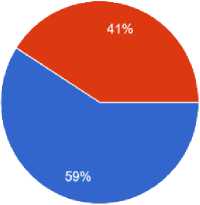

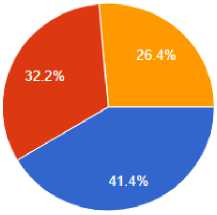

As can be inferred from the data visualization in Fig. 2 and Table 6 concerning age distribution among participants. Three groups (i.e., 23-30, 30-37, 38-45) scored almost the same percentage (around 27%) except for the 45< category which has scored the lowest participation rate of 16.3%.

Table 6. Participants by age

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

23-30 |

63 |

27.8 |

27.8 |

27.8 |

|

30-37 |

60 |

26.4 |

26.4 |

54.2 |

|

|

38-45 |

67 |

29.5 |

29.5 |

83.7 |

|

|

45< |

37 |

16.3 |

16.3 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

227 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

||

Age

227 responses

• 23-30

• 30-37

• 38-45

• 45<

Fig. 2. Participants by age

-

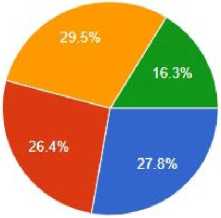

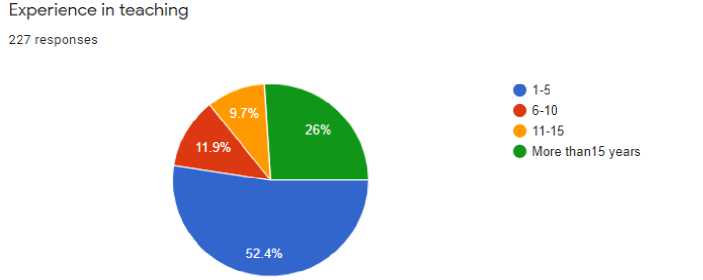

5.3. Experience in Teaching

100.000 teachers). The “more than 15 years of experience” category comes next with a participation rate of 26 %. The 6-10 and 11-15 account, respectively, for 11.9% and 9.7%.

-

5.4. Place of Work

Experience distribution among participants, based on Table 7 and Fig. 3, showed a dominant participation of the “1-5 years of experience” category accounting for 52.4%. This category mainly includes newly recruited teachers under limited contracts. This high score is, maybe, due to the fact that this category constitutes 1/3 of the population (around

Table 7. Participants by Experience

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

1-5 |

119 |

52.4 |

52.4 |

52.4 |

|

6-10 |

27 |

11.9 |

11.9 |

64.3 |

|

|

11-15 |

22 |

9.7 |

9.7 |

74.0 |

|

|

15< |

59 |

26.0 |

26.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

227 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

||

Fig. 3. Participants by Experience

The participants’ distribution by place of work, according to Table 8 and Fig. 4, showed dominant participation of teachers working in rural areas. This is, maybe, due to the fact that they are the dominant category in the overall population.

Table 8. Participants by place of work

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Rural area |

152 |

67.0 |

67.0 |

67.0 |

|

Urban area |

75 |

33.0 |

33.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

227 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

||

Place of work

227 responses

• Rural area

Ф Urban area

Fig. 4. Participants by place of work

-

5.5. Teachers Who Have Benefited From a Training to Teach Using the SbA

The results of this question showed that 41.4% of the sample have benefited from a training to teach through the SbA (see Table 9, Fig. 5). This is thanks to the Moroccan Ministry of Education efforts in providing continuous development programs in this respect. However, the training has not yet covered the entire population because the ministry trained only 1st and 2nd grade teachers starting from 2018. The ones who were not trained were probably teaching other grades in the last 3 years. The lack of training opportunity made 32.2% of the sample resort to selftraining.

Table 9. Teachers who have benefited from a training to teach using the syllabary

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Trained by the ministry |

94 |

41.4 |

41.4 |

41.4 |

|

Self-trained |

73 |

32.2 |

32.2 |

73.6 |

|

|

Not trained |

60 |

26.4 |

26.4 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

227 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

||

Have you benefited from a training to teach through the syllabary9 227 responses

Fig. 5. Teachers who have benefited from a training to teach using the syllabary

ф I was trained by the Moroccan Ministry of Education staff

Ф I was self-trained

• I was never trained to use the syllabary

-

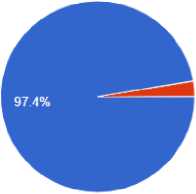

5.6. Participants’ Reliance on the SbA

Table 10 and Fig. 6 show that an overwhelming majority of teachers do rely on the syllable-based approach with a high rate of 97.4%. This high percentage is due to, at least, the fact that teachers are supposed to abide by the ministry’s policy. This category will be further examined for their use and perceptions of the SbA. Yet, there are always exceptions: 2.6% (6 out 227) of the participants reported not complying with the ministry’s decision to use the SbA. We will, later in this paper, explore the reasons behind this category’s refusal.

Table 10. Teachers’ reliance on the syllable-based approach

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Yes |

221 |

97.4 |

97.4 |

97.4 |

|

No |

6 |

2.6 |

2.6 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

227 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

||

Do you rely on the syllabary teaching method in teaching reading?

227 responses

Fig. 6. Teachers’ reliance on the syllable-based approach

-

5.7. Moroccan Teachers’ Use of the SbA

As shown in Table 11 and Fig. 6, the standard deviations (SD) are low meaning that the data is clustered around the mean in all the questions. This makes the mean interpretation meaningful. The Experiences Lived (LE) of the sample showed that the majority of Moroccan teachers rely on lesson planning before using the SbA approach as the mean is 2.74 (1= “I do not”, 2= “To some extent”, 3= “I do”), the mode and median both equal 3 which stands for “I do”. This is probably due to the SbA technicalities (visual words preparation, lesson planning, pedagogical aids, etc.). The same analysis applies to the second question as the majority of teachers rely on the teacher’s guide provided by the

Ministry. This is probably due to the fact that the concepts of the SbA are relatively new to Moroccan teachers. In this respect, they have also reported that they resort to reading other materials in order to help them use the SbA effectively (mean= 2.402, SD= 0.79). The same teachers use SbA concepts while addressing their students.

Accordingly, assigning reading homework is also one the practices Moroccan teachers do rely on (mean=2.638 with SD=0.65). This is, maybe, helping their students achieve greater fluency.

The only question which has scored differently in this questions’ set is the teachers use of ICT tools in the teaching through the SbA. Around half the teachers use ICT tools (mean 1.566) for that purpose. This is probably due to the fact that most teachers teach in rural areas where they have limited access to ICT tools.

Table 11. Moroccan teachers’ use of the syllable-based approach

|

N |

Mean |

Median |

Mode |

Std. Deviation |

||

|

Valid |

Missing |

|||||

|

Do you rely on lesson planning before teaching through the SbA? |

219 |

8 |

2.740 |

3.000 |

3.0 |

.4985 |

|

Do you rely on the pedagogical teachers' guide to teach reading lessons? |

219 |

8 |

2.470 |

3.000 |

3.0 |

.7249 |

|

Do you use the SbA concepts in teaching reading? |

217 |

10 |

2.166 |

2.000 |

2.0 |

.5933 |

|

Do you use ICT tools while teaching through the SbA? |

219 |

8 |

1.566 |

1.000 |

1.0 |

.7775 |

|

Do you assign reading homework focusing on SbA? |

218 |

9 |

2.638 |

3.000 |

3.0 |

.6524 |

|

Do you read other materials related to teaching reading through the SbA? |

219 |

8 |

2.402 |

3.000 |

3.0 |

.7917 |

Note. 1= “I do not”; 2= “To some extent”; 3= “I do”

-

5.8. Moroccan Teachers’ Use of the SbA Based on Gender

-

5.9. Moroccan Teachers’ Perceptions of the SbA

In order to test whether there are statistically significant differences in the SbA use based on gender, we have run a One-Way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Both genders, as shown in Table 12, have almost the same practices since the sig values were higher than the P value (= .05) except for the practice of assigning homework where the null hypothesis was rejected: sig. value was .001, [F (1,216) = 12.219, p= .05]. And since we cannot run a post hoc test (as we have only two groups), we resorted to comparing the two groups’ means. This showed that female participants (mean=2.762) assign more reading homework than male participants (mean=2.455).

Table 12. One-way ANOVA: Moroccan teachers’ use of the SbA based on gender

|

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

||

|

Do you rely on lesson planning |

Between Groups |

.160 |

1 |

.160 |

.644 |

.423 |

|

before teaching through the SbA? |

Within Groups |

54.004 |

217 |

.249 |

||

|

Total |

54.164 |

218 |

||||

|

Do you rely on the pedagogical |

Between Groups |

.087 |

1 |

.087 |

.165 |

.685 |

|

teachers' guide to teach reading |

Within Groups |

114.470 |

217 |

.528 |

||

|

lessons? |

Total |

114.557 |

218 |

|||

|

Do you use the SbA concepts in |

Between Groups |

.370 |

1 |

.370 |

1.052 |

.306 |

|

teaching reading? |

Within Groups |

75.657 |

215 |

.352 |

||

|

Total |

76.028 |

216 |

||||

|

Do you use ICT tools while teaching |

Between Groups |

.826 |

1 |

.826 |

1.369 |

.243 |

|

through the SbA? |

Within Groups |

130.964 |

217 |

.604 |

||

|

Total |

131.790 |

218 |

||||

|

Do you assign reading homework |

Between Groups |

4.946 |

1 |

4.946 |

12.219 |

.001 |

|

focusing on SbA? |

Within Groups |

87.426 |

216 |

.405 |

||

|

Total |

92.372 |

217 |

||||

|

Do you read other materials related |

Between Groups |

.546 |

1 |

.546 |

.870 |

.352 |

|

to teaching reading through the |

Within Groups |

136.093 |

217 |

.627 |

||

|

SbA? |

Total |

136.639 |

218 |

|||

In order to explore Moroccan teachers’ perceptions of the SbA, descriptive statistics were used and they have showed that all statements have in fact scored a mean no less than 3.6 (see Table 13). Also, the mode varies between 5= strongly disagree and 4= agree. The SDs are low so the data is automatically clustered around the mean. As a result, the participants, mostly agree with the statements examined in this 5-point Likert-scale. Thus, Moroccan students, according to their teachers, enjoy the syllabary activities; show significant improvement and fluency in reading competency thanks to the SbA; look forward to reading sessions; enjoy the SbA physical movements; and become more independent and confident at reading. The Experiences Lived of Moroccan teachers, on the other hand, yielded that these teachers advocate the SbA use, enjoy and recommend teaching through it; think that the syllabary is a learnercentered pedagogy; assume that it is preferably taught in student groups; and that peer-learning is enhanced during reading sessions.

The positive perceptions of Moroccan teachers towards the syllabary align with many studies as mentioned in the literature review. A study on children with disabilities conducted by [11] to test whether teaching two syllable types and one syllabication rule in a reading program would affect the spelling achievement of students with learning disabilities. The results showed that a substantial increase in spelling achievement for both the closed syllable spelling test and the silent syllable spelling test. Other studies with positives views towards the syllabary method include [16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22]

Table 13. Moroccan teachers’ perceptions of the syllable-based approach

|

N |

Mean |

Median |

Mode |

Std. Deviat ion |

||

|

Valid |

Missing |

|||||

|

My students enjoy the syllabary activities and its lesson steps |

221 |

6 |

4.321 |

4.000 |

4.0 |

.7077 |

|

Most of my students show significant improvement when teaching reading through the syllabary |

221 |

6 |

4.312 |

4.000 |

4.0 |

.7307 |

|

My students look forward to the next reading session |

221 |

6 |

4.081 |

4.000 |

4.0 |

.8105 |

|

My students enjoy the physical movements associated with the Syllabary |

221 |

6 |

4.543 |

5.000 |

5.0 |

.7162 |

|

My students become more independent as we progress using the syllabary |

221 |

6 |

4.000 |

4.000 |

4.0 |

.8893 |

|

My students are more willing to be assigned reading homework |

221 |

6 |

3.760 |

4.000 |

4.0 |

.9542 |

|

My students are more confident at reading |

221 |

6 |

4.005 |

4.000 |

4.0 |

.8555 |

|

My students get used quickly to the lesson steps of reading |

221 |

6 |

4.240 |

4.000 |

4.0 |

.7456 |

|

Most of students can read fluently by the end of the school year |

221 |

6 |

4.181 |

4.000 |

4.0 |

.7710 |

|

The Syllabary is useful to teach Arabic reading in the Moroccan context |

221 |

6 |

4.195 |

4.000 |

4.0 |

.8108 |

|

The syllabary is a learner-centered pedagogy |

221 |

6 |

4.240 |

4.000 |

4.0 |

.7985 |

|

The syllabary is preferably taught in student groups |

221 |

6 |

3.674 |

4.000 |

4.0 |

.9875 |

|

Peer-learning is enhanced during reading sessions |

221 |

6 |

4.131 |

4.000 |

4.0 |

.8180 |

|

I enjoy teaching reading through the syllabary |

221 |

6 |

4.267 |

4.000 |

5.0 |

.8013 |

|

My fellow teachers advocate using the syllabary |

221 |

6 |

4.118 |

4.000 |

4.0a |

.8763 |

|

I recommend using the syllabary |

221 |

6 |

4.326 |

4.000 |

5.0 |

.7993 |

Note. 1= “Strongly disagree”; 2= “Disagree”; 3= “Neutral”; 4= “Agree”; 5= “Strongly agree”

-

5.10. Moroccan Teachers’ Perceptions of the SbA Based on Gender

-

5.11. SbA Disadvantages According to Moroccan Teachers

In order to test whether there are statistically significant differences in Moroccan teachers’ SbA perceptions based on gender, ANOVA showed that there are no statistically significant differences since no Sig. values have exceeded the P value (= .05) as shown in Table 14.

Table 14. One-way ANOVA: Moroccan teachers’ perceptions of the SbA based on gender

|

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

||

|

My students enjoy the syllabary activities and its lesson steps |

Between Groups |

.179 |

1 |

.179 |

.355 |

.552 |

|

Within Groups |

110.012 |

219 |

.502 |

|||

|

Total |

110.190 |

220 |

||||

|

Most of my students show significant improvement when teaching reading through the syllabary |

Between Groups |

.285 |

1 |

.285 |

.533 |

.466 |

|

Within Groups |

117.172 |

219 |

.535 |

|||

|

Total |

117.457 |

220 |

||||

|

My students look forward to the next reading session |

Between Groups |

.208 |

1 |

.208 |

.315 |

.575 |

|

Within Groups |

144.326 |

219 |

.659 |

|||

|

Total |

144.534 |

220 |

||||

|

My students enjoy the physical movements associated with the Syllabary |

Between Groups |

.065 |

1 |

.065 |

.127 |

.722 |

|

Within Groups |

112.776 |

219 |

.515 |

|||

|

Total |

112.842 |

220 |

||||

|

My students become more independent as we progress using the syllabary |

Between Groups |

.675 |

1 |

.675 |

.853 |

.357 |

|

Within Groups |

173.325 |

219 |

.791 |

|||

|

Total |

174.000 |

220 |

||||

|

My students are more willing to be assigned reading homework |

Between Groups |

.219 |

1 |

.219 |

.239 |

.625 |

|

Within Groups |

200.071 |

219 |

.914 |

|||

|

Total |

200.290 |

220 |

||||

|

My students are more confident at reading |

Between Groups |

.126 |

1 |

.126 |

.172 |

.679 |

|

Within Groups |

160.869 |

219 |

.735 |

|||

|

Total |

160.995 |

220 |

||||

|

My students get used quickly to the lesson steps of reading |

Between Groups |

.003 |

1 |

.003 |

.006 |

.939 |

|

Within Groups |

122.286 |

219 |

.558 |

|||

|

Total |

122.290 |

220 |

||||

|

Most of students can read fluently by the end of the school year |

Between Groups |

.031 |

1 |

.031 |

.052 |

.819 |

|

Within Groups |

130.729 |

219 |

.597 |

|||

|

Total |

130.760 |

220 |

||||

|

The Syllabary is useful to teach Arabic reading in the Moroccan context |

Between Groups |

.565 |

1 |

.565 |

.858 |

.355 |

|

Within Groups |

144.069 |

219 |

.658 |

|||

|

Total |

144.633 |

220 |

||||

|

The syllabary is a learner-centered pedagogy |

Between Groups |

1.662 |

1 |

1.662 |

2.626 |

.107 |

|

Within Groups |

138.628 |

219 |

.633 |

|||

|

Total |

140.290 |

220 |

||||

|

The syllabary is preferably taught in student groups |

Between Groups |

.033 |

1 |

.033 |

.033 |

.855 |

|

Within Groups |

214.510 |

219 |

.979 |

|||

|

Total |

214.543 |

220 |

||||

|

Peer-learning is enhanced during reading sessions |

Between Groups |

.869 |

1 |

.869 |

1.301 |

.255 |

|

Within Groups |

146.325 |

219 |

.668 |

|||

|

Total |

147.195 |

220 |

||||

|

I enjoy teaching reading through the syllabary |

Between Groups |

.681 |

1 |

.681 |

1.061 |

.304 |

|

Within Groups |

140.568 |

219 |

.642 |

|||

|

Total |

141.249 |

220 |

||||

|

My fellow teachers advocate using the syllabary |

Between Groups |

.006 |

1 |

.006 |

.008 |

.927 |

|

Within Groups |

168.935 |

219 |

.771 |

|||

|

Total |

168.941 |

220 |

||||

|

I recommend using the syllabary |

Between Groups |

.836 |

1 |

.836 |

1.311 |

.254 |

|

Within Groups |

139.707 |

219 |

.638 |

|||

|

Total |

140.543 |

220 |

The dominant drawback expressed, according to Fig. 6, by teachers using the SbA in the Moroccan context is the time constraint with 177 votes out of 227 (i.e., 80%). The next drawback is lesson planning. In fact, 54.18% of the sample complained about the length of time the SbA lessons take to plan beforehand. 34% of teachers claim that they frequently have to consolidate students’ learnings because the syllabary approach is partially beneficial. Around 23% of teachers think that the syllabary confuses their students with too many syllables. The other reasons can be neglected because they constitute the views of 0.01% of the sample.

It is just a reading phase and not a method I

The syllabary is not effective ■

It emphasizes reading over comprehension I

The syllabary has a slow learning pace for fluent students I

Teaching tools in rural areas are missing I

The syllbary requires too many teaching tools I syllables to words transition is hard for some students I Combined grades make it to teach through the Syllabary ■

I do not have enough time to carry out all the lesson steps

I frequently have to consolidate reading learnings

Its lesson planning is more demanding

The syllabary method provides with too many syllables

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180

Fig. 7. Syllable-based approach disadvantages according to Moroccan teachers

-

5.12. Reasons behind Teachers’ Refusal to teach Through the SbA

As can be inferred from Fig. 8, half the teachers (3 out of 6) refuse to use the syllabary because (1) they do not have enough time to carry out all of its steps; (2) they do not find the text books to be useful; (3) they find it hard to teach reading through it; (4) they were not trained to use it; and (5) they think it is just not useful. Furthermore, two out of the six teachers claim that they do not rely on the SbA because they rarely achieve the lesson objective and that their students do not actively engage in reading lessons based on the SbA.

In this respect, a study by [6], where they examined the effectiveness of English rule-oriented syllabication instruction and phonogram identification on 108 second grade pupils, showed that both strategies were not effective in improving the “word attack skills” or reading comprehension. This raises the question of the syllabary effectiveness across languages because, as [12] argue, Spanish and French differ from languages such as Dutch, English, and German in terms of how syllables are rhythmically organized into words. This may mean that syllables play a different role in sounds’ production in different languages.

Other

I do not have much time to go through all of its…

I rarely achieve the lesson objective

Students do not actively engage during the lesson

The textbooks provided are not useful

I think it is not useful

Its pedagogical tasks are hard to carry out

Because I have not been trained to use it

0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5

Fig. 8. Reasons behind teachers’ refusal to teach through syllable-based approach

As a conclusion, by comparing the benefits and drawbacks of the syllabary reading approach, it can be safely assumed that the method’s advantages outweigh its drawbacks in the Moroccan context. Therefore, there will only be a need to enhance its use and minimize its disadvantages and hopefully the international reading scores of Moroccan pupils will be enhanced within the coming four to six years. It is also worth noting that the Moroccan Ministry of education is adopting teaching at the right level approach which aims as well at enhancing Arabic and French reading as well as arithmetic competency. More important, reading difficulties cannot disappear overnight or through a unique magic reading strategy. That is because each student has unique needs that can range from dyslexia, sight problems, to fear of learning, etc. Therefore, individual consolidation is deemed necessary in order to increase literacy rates as much as possible.

6. Conclusion

All in all, the need to tap into the academic discussion about the syllabary was the reason behind conducting this research. The present article adds up to the studies advocating the use of the Syllabary. In fact, the study revealed that Moroccan teachers perceive the syllable-based approach to be effective in the Moroccan context. Still, the complaints they have raised should be addressed by policy makers in order to enhance SbA return on investment. Regarding the issue of sessions time, the ministry could raise the reading session time to 60 minutes instead of 45 minutes, provide teachers with shorter sample lesson plans, train the remaining 26.4% of teachers who have not yet been trained to teach through the SbA, and seek more technology integration.

Furthermore, the study limitations included the fact that the questionnaire did not provide respondents with choices in the regions question. As a result, the teachers wrote the regions names freely in both French and Arabic. In order to solve this issue, the researchers recoded the regions’ names and counted the answers. As a future recommendation, other researchers could conduct a pre-test post-test study of the same topic involving a control group which would not be taught while the experimental group would be taught through the syllabary. This kind of study will enhance our understanding of the SbA effectiveness and drawbacks more accurately. Also, more studies are needed on SbA internal organization and durational and coarticulatory patterns of MSA and Darija (Moroccan Arabic) as conducted on other languages (see [13, 23-25]).

This study constitutes a reference to future researchers in the area of Arabic reading enhancement as it reviews studies that have been published on the topic while also enriching them with the present field questionnaire that collected significant data about the SbA. Finally, SbA, in our opinion, can be more effective if used by preconceived content mediated by ICT.

Список литературы The Impact and Effectiveness of the Syllable-based Reading Approach on Moroccan Pupils’ Reading Competency

- International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement. (2017). Pirls 2016 International Results in Reading. TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College and International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). Retrieved from: http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/pirls2016/international-results/wp-content/uploads/structure/CompletePDF/P16-PIRLS-International-Results-in-Reading.pdf

- Gleitman, L. R., & Rozin, P. (1973). Teaching reading by use of a syllabary. Reading Research Quarterly, 8(4), 447–483. https://doi.org/10.2307/747169

- Assou, M., Ouarach, M., Benzakour, A., Oukacem, A., Elfilali, A., Al-Azraq, A., & Eddarkaoui, M. (2017). المفيد في اللغة العربية: دليل الأستاذ والأستاذة [The useful guide in teaching Arabic: Teacher’s guide]. Morocco: Moroccan Ministry of Education.

- W. Ziegler, I. Aichert, and A. Staiger, “Syllable- and Rhythm-Based Approaches in the Treatment of Apraxia of Speech,” Perspectives on Neurophysiology and Neurogenic Speech and Language Disorders, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 59–66, Oct. 2010, doi: 10.1044/nnsld20.3.59.

- B. Müller, T. Richter, and P. Karageorgos, “Syllable-based reading improvement: Effects on word reading and reading comprehension in Grade 2,” Learning and Instruction, vol. 66, p. 101304, Apr. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101304.

- G. Canney and R. Schreiner, “A Study of the Effectiveness of Selected Syllabication Rules and Phonogram Patterns for Word Attack,” Reading Research Quarterly, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 102–124, 1976, doi: 10.2307/747237.

- R. Hamdi, S. Ghazali, and M. Barkat-Defradas, “Syllable Structure in Spoken Arabic: a comparative investigation,” Lisbonne, Portugal, Sep. 2005. Accessed: Oct. 10, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01740924

- F. Guillen and D. Elida, “Qualitative Research: Hermeneutical Phenomenological Method,” Journal of Educational Psychology - Propositos y Representaciones, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 217–229, 2019.

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5, 1-4. - References - Scientific Research Publishing.” https://www.scirp.org/(S(lz5mqp453edsnp55rrgjct55.))/reference/referencespapers.aspx?referenceid=2258299

- U. C. Bureau, “Survey Questionnaire Construction,” Census.gov. https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/2006/adrm/rsm2006-13.html.

- Taylor, T. E., (1997). The effects of Teaching Two Syllable Types and One Syllabication Rule on the Spelling Achievement of Students with Learning Disabilities. Grand Valley State University. Allendale, Michigan. Available : https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1394&context=theses

- Croot, K., & Rastle, K. (2004). Is There a Syllabary Containing Stored Articulatory Plans for Speech Production in English. Australian International Conference on Speech Science & Technology (376-381). Macquarie University.

- Cholin, J., (2008). The Mental Syllabary in Speech Production: an Integration of Different Approaches and Domains. Aphasiology, 22(11), 1127–1141. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030701820352

- Binaoui, A., Moubtassime, M., Belfakir, L., (2022). The Effectiveness and Impact of Teaching Coding through Scratch on Moroccan Pupils’ Competencies. [In press] International Journal of Modern Education and Computer Science, Vol.14, No.5, pp. 44-55, 2022.

- Ennaji, M., Makhoukh, A., Es-Saidy, H., Moubtassime, M., Slaoui, S. (2004). A Grammar of Moroccan Arabic. Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University. Available : https://pdfslide.net/documents/a-grammar-of-moroccan-arabic-languages-y-grammar-of-moroccanroyaume-du.html

- I. Weyers and J. L. Mueller, “A Special Role of Syllables, But Not Vowels or Consonants, for Nonadjacent Dependency Learning” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, vol. 34, no. 8, pp. 1467–1487, 2022, doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_01874.

- B. J. Kröger, T. Bekolay, and M. Cao, “On the Emergence of Phonological Knowledge and on Motor Planning and Motor Programming in a Developmental Model of Speech Production,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 16, 2022, doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.844529.

- B. A. Headen, J. M. Venuto, and L. E. James, “High-frequency first syllables facilitate name–face association learning,” Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 2022, doi: 10.1177/17470218221078851.

- A. D. Campos, H. M. Oliveira, and A. P. Soares, “On the role of syllabic neighbourhood density in the syllable structure effect in European Portuguese,” Lingua, vol. 266, 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2021.103166.

- P. Hallé, L. Manoiloff, J. Gao, and J. Segui, “Monitoring internal speech: an advantage for syllables over phonemes?,” Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 22–41, 2022, doi: 10.1080/23273798.2021.1941146.

- Q. Qu, C. Feng, F. Hou, and M. F. Damian, “Syllables and phonemes as planning units in Mandarin Chinese spoken word production: Evidence from ERPs,” Neuropsychologia, vol. 146, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2020.107559.

- L. Baqué, “How do persons with apraxia of speech deal with morphological stress in Spanish? A preliminary study,” Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, vol. 34, no. 1–2, pp. 131–168, 2020, doi: 10.1080/02699206.2019.1622155.

- J. Alderete and P. G. O’Séaghdha, “Language generality in phonological encoding: Moving beyond Indo-European languages,” Language and Linguistics Compass, vol. 16, no. 7, 2022, doi: 10.1111/lnc3.12469.

- D. Ramoo, C. Romani, and A. Olson, “Lexeme and speech syllables in English and Hindi. A case for syllable structure,” in Trends in South Asian Linguistics, 2021, pp. 415–462. doi: 10.1515/9783110753066-016.

- J. A. A. Engelen, “The In-Out Effect in the Perception and Production of Real Words,” Cognitive Science, vol. 46, no. 9, 2022, doi: 10.1111/cogs.13193.