The impact of precarization on the standard of living and employment situation of Russian youth

Автор: Popov A.V.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social and economic development

Статья в выпуске: 6 т.16, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The study of precarization implications focuses on young people who are facing serious problems on the way to stable employment. The lack of clear competitive advantages in the labor market complicates employment in the formal sector of the economy, where workers have access to an extensive system of social guarantees. In this regard, young people often feel vulnerable and uncertain about their future. Despite the relevance of the problem and wide discussion, there are not many specific empirical studies in this area. The aim of the paper is to determine the impact of precarization on the standard of living and the employment situation of young people. The information base is represented by the data of the Russia Longitudinal Monitoring Survey conducted by the Higher School of Economics for 2021 (30th round). Based on the original toolkit, the scale of precarious work was estimated depending on the concentration of precarization indicators and taking into account individual parameters of respondents. The indicators were calculated using the method of multivariate frequency distribution of attributes. According to the results obtained, the overwhelming majority (almost 80%) of young people are involved in precarious work. To a much lesser extent, this applies to the part of youth that has a high level of education, ICT skills and is engaged in skilled labor. The depth of precarization penetration is also closely linked to per capita income. As its size increases up to two subsistence minimums, the share of those involved in precarious work decreases significantly; and in this regard it does not matter what part of income is used for consumption. In conclusion, we substantiate proposals to counter the threats of precarization for young people. Prospects for further research are connected, first of all, with the identification of educational and professional trajectories that have a negative impact on employment stability.

Precarization, standard of living, employment, youth, precarious work, labor market, employment quality, youth policy

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147242469

IDR: 147242469 | УДК: 331.104 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2023.6.90.14

Текст научной статьи The impact of precarization on the standard of living and employment situation of Russian youth

The research was supported by Russian Science Foundation grant 22-28-01043 project/22-28-01043/) at Plekhanov Russian University of Economics.

Employment precarization as a global process of disruption of labor relations is actively penetrating in human life all around the world. Young people are no exception, as they face many barriers to entering the labor market, forcing them to turn more often than others not only to non-standard employment forms (Bessant et al., 2017), but also to the grey economy (Shehu, Nilsson, 2014). These kinds of practices allow gaining necessary work experience, financial independence, etc., but they invariably lead to vulnerability and social insecurity. Staying in such conditions for a long time has far-reaching consequences, up to falling into the “precarity trap” that prevents career growth and improvement of positions in society (Standing, 2011, pp. 48–49). In such a situation, instability becomes a lifestyle which determines all future behavior, regardless of educational and other achievements. At the same time, young people often do not see it as a problem and perceive what is happening as personal failures or temporary difficulties that should be simply endured (Mrozowicki, Trappmann, 2021).

Despite the relevance of the issues of youth’s transit to stable employment, there are only a few empirical studies in this field that could shed light on the wide range of negative effects of precarization. In the scientific literature, it is possible to find statements about deterioration of success level and reduction of time devoted to studies (Srsen, Dizdarevic, 2014); emotional exhaustion and dissatisfaction with life (Umicevic et al., 2021); reluctance to have children due to the inability to provide them with proper care (Chan, Tweedie, 2015); difficulties in socialization (Miguel Carmo et al., 2014), etc. In this case, we are talking about consequences beyond the social and labor sphere. Equally important are threats directly related to the workplace. They typically involve working conditions and related aspects of employment, which can also be considered as precarization indicators. There is no consolidated view on this issue. However, the practice-oriented thesis of normalizing destabilizing practices deserves much more attention. In particular, when the degree of precarization increases, the problematization of precariousness of working conditions among young workers does not increase (Kuchenkova, 2022, p. 116), while a high level of education and qualifications is less and less often a protective factor against vulnerability in the labor market (Lodovici, Semenza, 2012). All these things only strengthen the interest in this topic.

The aim of our research is to determine the impact of precarization on the standard of living and the employment situation of young people. The distinctive feature of this work is the application of an original methodology for estimating the extent of precarious work by taking into account certain characteristics of individuals. One such characteristic is information and communication technology (ICT) skills, which play an increasing role in the modern labor market. In addition to finding the patterns stated in the paper, the proposed approach helps to better understand whether digital competencies contribute to employment stability.

Degree of elaboration of the problem

Studying the impact of precarization on the standard of living and the employment situation of young people is a serious challenge for science. There are many debatable provisions and gaps in this issue, primarily due to the novelty of the research area itself, despite the presence of certain developments in relation to some of its components. For instance, the evolution of views on social well-being has gone from purely quantitative assessments of the income indicator to the extensive consideration of various aspects of human development (Gasper, 2007). Similar is the case with questions of employment quality, which subsequently covered the entire working life of employees (Level and Quality..., 2022). In addition to education and qualifications, more and more parameters are taken into account that determine the prospects of personal position in the labor market1.

In turn, the phenomenon of employment precarization, widely discussed in scientific literature, is just completing the stage of initial conceptualization (Odegov, Babynina, 2018; Melges et al., 2022) and is often criticized (Choonara, 2020), which does not prevent scientists from making attempts to assess its multifaceted consequences. The accumulated experience in this area is fragmentary and poorly generalizable, which imposes limitations on the ability to conduct applied research, especially when it comes to the need to identify certain relationships.

Methodological tools for analyzing the process of precarization are highly variable and largely depend on the criteria underlying the assessment (Tab. 1) . In the course of the study, we tried to outline certain frameworks, related both to methodological problems (the discussion of precarity and precarious work (Popov, Soloveva, 2020) and to the issues of accessibility of the information base and justification of the list of used indicators. In particular, the limited availability of official statistics in terms of accounting for various manifestations of precarization leads to the fact that specialists increasingly turn to sociological methods of research. In this case, usually, a large number of indicators are used, which can be combined into separate blocks characterizing the level of remuneration, social protection, typical working conditions, etc. As a result, there is a shift of emphasis toward comprehensive and index-based approaches that allow covering a variety of aspects of precariousness.

Ultimately, despite the fact that the diversity of viewpoints makes it difficult to compare the results of numerous studies, it has a positive effect on the formation of a common understanding of the effects of the phenomenon under consideration. At present, two approaches reveal them. The first one is based on the application of qualitative research methods, including in-depth interviews, expert surveys, focus groups, etc. They make it possible to form a holistic view of the impact of precarization process on the standard of living and the employment situation of the population by obtaining detailed information about the respondent’s working life. Case studies of specific industries or professions are very illustrative (Bohle et al., 2004; Bone, 2019), but it is impossible to talk about scaling or quantification of the research results. In these conditions more advantageous are mass survey data, the processing of which is carried out with the help of conjugation tables or more advanced mathematical tools. At the same time, despite the apparent universality of the approach, it has limitations when studying certain categories of the population, which is due to the complexity of sample construction and subsequent data collection. It is not by chance that in the scientific literature there are only some publications devoted to the comparative analysis of the situation of workers of different ages in precarious labor relations (Jetha et al., 2020; Kuchenkova, 2022). Most often, attention is paid to a single group.

Table 1. Criteria bases and indicator base for identifying employment precarization

|

Approach / example |

Indicator base |

Advantage of approach |

Disadvantage of approach |

|

Criterion basis: embodiment of employment precarization |

|||

|

Approach based on addressing the category of “precariat” (Precariat..., 2020) |

Indicators characterizing limited opportunities for implementing labor, civil, political and other rights |

Consider precarization as a process that has become an integral feature of modern society |

Difficulty of drawing a clear parallel between employment precarization and the precariat. Disunity of the new class |

|

Approach based on addressing the category of “precarious work” (Precarious Employment..., 2018) |

Indicators characterizing employee’s vulnerability and social insecurity |

Conceptual relationship of the concepts of “employment precarization” and “precarious work” |

Necessity to take into account the criterion of involuntariness to distinguish between “nonstandard employment” and “precarious work” |

|

Criteria basis: specifics of information base |

|||

|

Approach based on the use of official statistics data (Cranford et al., 2003) |

Indicators characterizing the coverage of the population with the least protected employment forms (part-time, temporary, casual, etc.), the scale of vulnerable employment and the informal economy, the size of wages, nonstandard working conditions |

Availability of information base and possibility of interregional comparisons |

Limitations of the list of available indicators and difficulty of correlating them with precarization theory |

|

Approach based on the use of initiative sociological surveys data (Shkaratan et al., 2015) |

Indicators broadly characterizing specifics of working conditions: from wage rates and availability of social guarantees to the autonomy and voting rights of workers. Specific formulations depend on the research tools used |

Availability independently determine assessment tools, indicator base, sampling, etc. |

Labor intensity of information gathering and interregional comparisons |

|

Criteria basis: assessment tools |

|||

|

Approach based on the use of private indicators (Khusainov, Alzhanova, 2017) |

Indicators characterizing the level of labor income, informal employment, job vulnerability |

Simplicity of calculations |

Limited range of precarization features affected |

|

Integrated approach (Kuchenkova, Kolosova, 2018) Index approach (Cassells et al., 2018) |

Indicators characterizing the specifics of working conditions in the broadest sense: from wage rates and availability of social guarantees to the autonomy and workers’ voice |

Accounting for multifaceted manifestations of precarization |

Difficulty in selecting indicators and justifying their reconciliation procedure |

|

Source: own compilation. |

|||

Materials and methods

The logic of the paper is determined by the results of many years of research conducted by members of the scientific team of the RSF project 22-28-01043. Under precarious work we understand the labor relations forced on an employee, which are accompanied by partial or complete loss of labor and social guarantees based on an open-ended employment contract, work in the mode of standard working hours (full-time, normal working week) in employer’s territory. To assess this condition, we use a set of objective indicators (Fig. 1) , formed taking into account previously conducted studies and provisions of the International Labour Organization2.

In total, we identified two groups of nine indicators, which had been tested for multicollinearity and supported by the expert community (Bobkov et al., 2022a). The first group contains key precarization indicators: (1) employment for hire on the basis of verbal agreement without documentation, (2) level of income from primary employment that does not ensure the sustainability of households’ financial situation3, (3) forced unpaid leave at employer’s initiative, (4) absence of paid leave, (5) reduction of wages or working hours by an employer. The presence of at least one of these serves as a criterion for classifying a person as precariously employed. Non-key precarization indicators, characterizing the depth of this unsustainability, form the second group of indicators. These are: (6) self-employment in the informal sector, (7) wage arrears, (8) unofficial (partially or fully) income from employment, (9) deviating from standard working hours (working week of more than 40 or less than 30 hours at the main workplace).

Figure 1. Employment precarization indicators

Key indicators of employment precarization

-

• Employment on the basis of verbal agreement without documentation.

-

• Level of income from primary employment that does not ensure the sustainability of households’ financial situation.

-

• Forced unpaid leave at employer’s initiative.

-

• Absence of paid leave.

-

• Reduction of wages or working hours by an employer.

Non-key indicators of employment precarization

-

• Self-employment in the informal sector.

-

• Wage arrears.

-

• Unofficial (partially or fully) income from employment.

-

• Deviating from standard working hours (working week of more than 40 or less than 30 hours at the main workplace).

Source: (Bobkov et al., 2023, p. 28).

Depending on the concentration of key and non-key precarization indicators, several categories of economically active population emerge:

-

• sustainable employed (there are no precarization indicators);

-

• transition group (there are non-key precarization indicators);

-

• precariously employed with moderate (1–2 key indicators), high (1–2 key indicators combined with any number of non-key indicators) and the highest concentration (3–5 key indicators) of precarization traits.

Special attention is paid to the unemployed as an extreme form of precarization. This is due to the fact that people with no permanent income or gainful occupation are most vulnerable. As a rule, in such circumstances, the planning horizon is considerably narrowed and domestic problems come to the fore. The social protection system plays an important role here, as it helps to maintain a minimum level of consumption, but cannot ensure the overall sustainability of a person in need.

The feature of the subsequent analysis is the focus on determining the impact of precarization on the employment situation of young people and their standard of living. In the first case, we took into account the parameters of education, qualifications and ICT skills that reflect the competitiveness of individuals in the labor market, and in the second case it was the parameters of household income using social standards for material affluence (Bobkov et al., 2022b). Table 2 presents a detailed description of each of them. It is also important to emphasize that the proposed indicator of the standard of living has much in common with the indicator of earnings from primary activity used to identify the precariously employed. However, our methodology considers the wage threshold, and in the process of estimating the effects of precarization, we not only refer to a broader category that takes into account household size, but also distinguish several income groups. This perspective makes it possible to follow in detail the changes in the incidence of precarious work with increasing material wealth.

Table 2. Parameters determining the standard of living and the employment situation of young people

|

Parameter |

Description |

|

Employment situation |

|

|

Education |

It is determined on the basis of the achieved level of education: 1) without vocational education; 2) with secondary vocational education; 3) with higher education and above. |

|

Skill |

It is determined on the basis of belonging to an occupation group according to the All-Russian Classifier of Occupations (OKZ): 1) engaged in unskilled labor (groups 9 “Unskilled workers” and 03 “Private military personnel”); 2) engaged in skilled labor (groups 4–8 “Employees engaged in preparation and execution of documents, accounting and servicing”, “Employees of service and trade, protection of citizens and property”, “Skilled workers of agriculture and forestry, fish farming and fishing”, “Skilled workers of industry, construction, transport and workers of related occupations”, “Operators of production plants and machines, assemblers and drivers”); 3) engaged in the most skilled labor (groups 1–3 “Managers”, “Specialists of the highest qualification level”, “Specialists of the middle qualification level” and 01–02 “Officers of active military service”, “Non-officer military personnel”) |

|

ICT skills |

It is determined on the basis of the relationship between the level of ICT skills and professional activity: 1) basic skills not related to professional activity (low level); 2) user skills related to professional activity (medium level); 3) specialized skills necessary for solving professional tasks in the ICT sphere (highest level). |

|

Standard of living |

|

|

Cash income |

It is determined on the basis of social standards of households: 1) least well-off (less than 1 SM); 2) low-income (1–2 SM); 3) below-average well-off (2.0–3.1 SM); 4) medium- and high-income (over 3.1 SM). |

We tested this research toolkit on the data of the 30th round of the Russia Longitudinal Monitoring Survey conducted by the Higher School of Economics (RLMS-HSE)4. At first, we selected respondents aged 15 to 35 from among the employed and unemployed; we divided 1,895 observations into several groups in accordance with the specified conditions. After that, we calculated indicators of volatility for each of them (method of multivariate frequency distribution of attributes). Based on the results of the analysis, we substantiated the proposals for mitigating the threats of the impact of precarization on the quality of employment and the standard of living of young people.

Research results

Relationship between precarization and the employment situation of young people

As we have mentioned above, our study reveals the relationship between precarization and employment situation by taking into account the level of qualifications, education and ICT skills of generational groups of the economically active population. According to the calculations on the RLMS data for 2021, the majority of young people are in precarization regardless of the characteristics considered (Tab. 3) . The share of sustainably employed does not exceed 8%, which together with the transition group gives only 21%. In this regard, only the fact that the maximum concentration of

Table 3. Distribution of youth by presence and concentration of precarization indicators and the employment situation, 2021, %

Skilled work (codes 4–8 according to OKZ) provides young people with greater employment stability, as evidenced by the increase in the share of respondents with zero concentration of precarization indicators. Despite the obvious conclusion, it is important to emphasize how big the differences are with the effects of unskilled labor. In the current realities, it can hardly ensure the sustainability of a young worker, which brings us back to the debate on the principles of decent work for all5.

Among those employed in skilled work, there are not many young people with both vocational education and an average level of ICT skills (directly related to the performance of job duties), but it is here that the occupancy rate of the groups of the precariously employed decreases as the concentration of precarization indicators increases. The same is the case with those performing the most skilled work (codes 1–3 and 01–02 in OKZ). Moreover, with growing ICT skills, the gap in the representation of polar groups – stably employed and precariously employed with the highest concentration of precarization indicators – increases in favor of the former. Consequently, the stability of young workers’ position depends not only on the traditional characteristics of job seekers, but also on the ability to apply digital competencies in labor activities, if such an opportunity is available, since not all professions involve the use of information and communication technologies.

The extreme form of precarization is unemployment, which we consider as a state of temporary unemployment characterized by the loss of regular earnings, professional and social status. In such conditions, the planning horizon narrows to a minimum, and the vulnerability of the labor market situation reaches its peak. As we have mentioned, young people experience serious problems in finding employment. First of all, this situation concerns young people, who often have neither specialty nor work experience. Although youth unemployment is higher than among adults6, the situation normalizes after the age of 257, as many of them successfully find jobs.

The data of our calculations show that in the structure of unemployed youth surveyed in the framework of RLMS in 2021, almost half of them have secondary vocational and above education and ICT skills (Tab. 4) . They are rather qualified specialists with digital competencies in demand in the modern labor market. We can assume that the employment process for them will not last long and employment problems will soon be solved. Against

Table 4. Distribution of unemployed youth by employment situation, 2021

|

Employment situation |

Characteristics of groups |

Share of unemployed youth, % |

|

|

Level of ICT skills |

Level of education |

||

|

Unemployed with secondary vocational and above education and level of ICT skills |

Highest level |

Secondary vocational and above |

7.8 |

|

Medium level |

Secondary vocational and above |

39.8 |

|

|

Unemployed with secondary vocational and above education and low level of ICT skills |

Low level |

Higher education and above |

-* |

|

Low level |

Secondary vocational |

16.4 |

|

|

Unemployed without vocational education and with low to medium level of ICT skills |

Medium level |

No vocational education |

6.3 |

|

Low level |

No vocational education |

29.7 |

|

* Insufficient observations to make an assessment. Source: assessment based on RLMS data.

this background, about one third of young people looking for a job do not have a profession, and most of them cannot boast a high level of ICT skills. In this case, the chances of success are significantly reduced due to the lack of clear advantages of job seekers compared to more experienced competitors. The last group, comprising 16% of respondents, consists of unemployed people with secondary vocational education and low ICT skills.

The results obtained for employed and unemployed confirm the thesis about youth’s vulnerability in the labor market. Precarization indicators are clearly visible in all groups under consideration. A higher level of education and ICT skills, as well as employment in skilled labor, if not completely avoid precariousness, then significantly reduce the depth of its penetration into working life , which in the worst conditions affects everyday practices. At the same time, the developed qualities of young people hardly serve as a guarantee of protection against unemployment as an extreme form of precarization, according to the recent data, but in this case, the probability of a relatively quick transit from study to stable work is sharply increased. For example, in Germany it averages one year, although depending on the situation it can increase up to 8 years (in particular, for young men who chose the early employment trajectory) (Stuth,

Jahn, 2020). Russia’s experience shows that such a transition can take up to about 4 years when it did not work out the first time (Russian Youth..., 2016, pp. 63–64). In this regard, young people’s entry into the labor market should be meaningful in terms of ensuring a balance between gaining in-demand competencies, including digital competencies, and acquiring the necessary work experience.

The impact of employment precarization on the standard of living of young people

The study focused on the effects of precarization on the standard living of economically active population, since material prosperity remains one of the most important criteria of social well-being. We considered the sustainability of workers’ situation through the prism of income levels. The calculation on RLMS data for 2021 showed that the share of poor young people increases with growing concentration of precarization indicators (Tab. 5) . Moreover, the differences between people with per capita incomes of less than one subsistence minimum (SM) and those who spend less than one consumption basket of subsistence minimum (CBSM) are insignificant. In both cases, the share of the sustainably employed is inferior to the occupancy of each of the precariously groups, the latter of which is characterized by the largest representation.

Table 5. Distribution of youth by presence and concentration of precarization indicators and the standard of living, 2021, %

|

Group according to living standard type |

Group by presence and concentration of precarization indicators |

||||

|

Sustainably employed |

Transition group |

Precariously employed |

|||

|

With moderate concentration of indicators |

With high concentration of indicators |

With the highest concentration of indicators |

|||

|

The least well-off (poor) |

|||||

|

With per capita income less than 1 SM |

7.7 |

5.9 |

9.2 |

10.3 |

15.3 |

|

With income used for consumption of less than 1 CBSM |

21.4 |

24.7 |

29.4 |

30.4 |

36.5 |

|

Low-income |

|||||

|

With per capita income of 1–2 SM |

32.3 |

46.8 |

52.0 |

53.3 |

53.5 |

|

With income used for consumption of 1–2 CBSM |

57.2 |

57.2 |

55.5 |

57.0 |

52.7 |

|

Wealthy below average |

|||||

|

With per capita income of 2.0–3.1 SM |

32.3 |

30.0 |

29.8 |

26.8 |

24.1 |

|

With income used for consumption of 2.0–3.1 CBSM |

12.4 |

13.6 |

13.7 |

9.8 |

10.8 |

|

Middle- and high-income |

|||||

|

With per capita income of 3.1 SM and more |

27.7 |

17.3 |

9.0 |

9.6 |

7.1 |

|

With income used for consumption of 3.1 CBSM and more |

9.0 |

4.5 |

1.4 |

2.8 |

0.0 |

|

Note: SM – subsistence minimum; CBSM – consumption basket of subsistence minimum. In the calculation, we used different values of indicators depending on the region. Source: assessment based on RLMS data. |

|||||

The category of low-income young people with per capita incomes at the level of 1–2 SM acquires a relatively positive coloring only if we are talking about 1–2 CBSR. In such a situation, the equality between the polar groups is achieved, facilitated by a marked increase in the share of the sustainably employed. Otherwise, the overall situation remains rather tense, which is especially evident in the case of those whose income is limited to two SMs. While the occupancy rate of the unstable groups is practically unaffected, in the others it tends to decrease. On this basis, it follows how sensitive the line is between similar income and consumption levels among the low-income strata. Nothing similar is observed in wealthier strata.

Young people with per capita incomes above two SM are less and less likely to exhibit high levels of precarization, regardless of how much of their money is used for consumption. The aggregate share of precariously employed remains impressive, but it is safe to say that there has been a significant change in the quality of jobs, which, in addition to high earnings, represent a fundamentally new level of social security. This statement is especially true for high-income groups, although even here young people face vulnerability, which demonstrates the difficulty of ensuring employment stability in modern conditions.

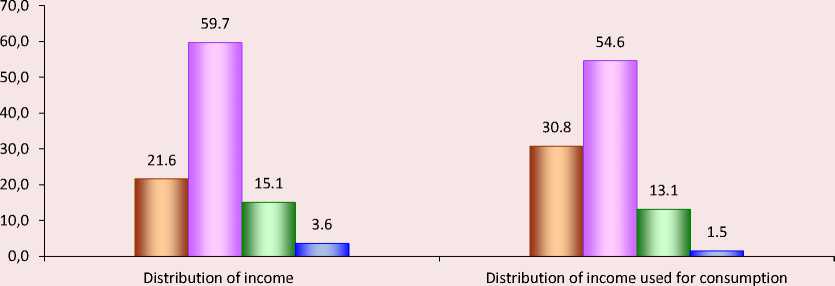

Unemployment as an extreme form of preca-rization does not have a pronounced specificity in the context of income groups (Fig. 2) . For instance, better-off young people are less likely to be in the process of job search. This pattern can be traced for all the categories, except for those with incomes/ consumption less than one subsistence minimum, where differences in wealth are insignificant.

Figure 2. Distribution of unemployed youth by the standard of living, 2021, %

□The least well-off (less than 1 SM) □ Low-income (1-2 SM)

□ Wealthy below the average (2.0-3.1 SM) □ Meduim and high-income (3.1 SM and more)

Note: SM – subsistence minimum. In the calculation, we used different values of the indicator depending on the region. Source: assessment based on RLMS data.

At the same time, we should remember that young people may be part of a parental household and feel less discomfort in the absence of a permanent source of income than adults.

We should emphasize that the phenomenon of precarization has a mixed impact on young people. Taking into account the negative effects, about which the scientific literature says much, primarily in relation to everyday life, the very opportunity to gain work experience and consolidate professional skills in practice has many more positive aspects in comparison with unemployment. In this regard, the duration of transit to stable employment comes to the fore. One of the reasons is the low standard of living of youth who have to put up with the precariousness of their situation. Our results show that the depth of precarization penetration is closely related to the size of per capita income. For young people, this means not only serious problems with consumption, but also feeling all the burdens of social insecurity. Such a long-range development can lead to falling into “precarity trap” from which it can be difficult to escape.

Proposals to mitigate the threats of precarization to the quality of employment and the standard of living of young people

The study shows how destructive the effects of precarization can be for economically active young people. The lack of social guarantees and career opportunities, low wages and irregularity of their payments go far beyond the employment sphere and affect everyday activity. Due to the large number of barriers to successful employment, many are willing to accept this state of affairs. The opportunity to gain work experience and financial independence usually compensates for all the disadvantages. In this regard, the problems of transit from study to stable employment, which is often seen as a search for any paid job, come to the fore. In modern times, this approach requires a radical revision, which entails the need to improve the existing institutional environment.

Without revealing details about the state of the vocational education system in Russia, let us emphasize the importance of continuing efforts to bring the level of training closer to the real needs of the economy through closer cooperation with employers. We are talking both about well-known areas such as the organization of industrial practice and project work, the development of professional standards, the introduction of the social order mechanism, etc., and about actual measures, for example, related to the implementation of graduate employment programs. The list of joint actions can be rather wide, but all of them should be consonant with the idea of forming a demanded specialist who realizes their professional trajectories and prospects. Digital competencies play an important role here, as their level of proficiency should enable young people to use them in their working life to solve specific applied tasks. A good support was the Digital Professions project, through which, with the support of the state, everyone could learn an IT profession. In 2022, the initiative was frozen indefinitely, which is alarming given the lack of emphasis on ICT skills in the Long-Term Program to Promote Youth Employment for the period up to 20308.

The ecosystem of professional support for young people cannot fully exist without the active participation of the state employment service9. Usually, unemployed youth are less likely to use its services, which is explained, among other things, by the low quality of vacancies offered, as a result of which independent job search allows them to apply for higher positions (Giltman et al., 2022, p. 210). All these situations bring us back to the issues of increasing the attractiveness and efficiency of employment offices, which are being modernized within the framework of the national project “Demography”10. To date, it is rather difficult to judge the results of such transformations, both in terms of popularization of formal employment channels and the establishment of interaction with the subjects of the labor market as a whole. At the same time, the need for fundamental changes has been long overdue, especially in the regional periphery, where, against the background of limited opportunities, it is more complicated to obtain quality vocational education and employment problems are much more pronounced (Popov, Soloveva, 2023). This contributes to the migration outflow of young people, which only exacerbates the disproportions of spatial development and, as a consequence, the situation of those who decided to stay. Despite the complexity of the functioning of employment offices (from the modest staff and low salaries to the instability of the Unified Digital Employment Platform “Work in Russia”), it is they that should become a reliable support for young people in the social and labor sphere.

If we do not mention the objective and subjective barriers to the labor market, then young people’s exposure to precarization is itself due to their greater involvement in non-standard employment forms (for example, to combine study and work), which often translate into decent work deficits. This type of discussion is important in understanding perspectives on the sustainability of employment situation. There is no consensus, but the International Labour Organization recommends regular work to address legislative gaps (even to the point of restricting the use of certain employment forms), strengthen collective bargaining systems, improve social protection, and implement socio-economic policies to manage social risks and facilitate the transition to standard employment11. For instance, the current mechanisms of social partnership and regulation of remote labor, “expansion” of civil law in labor relations (Kurennoy, 2022), etc. are criticized in Russian practice. In connection with the above, the issues of improving labor legislation should be subjected to a broad public discussion to take into account the interests of all subjects of the labor market. In turn, the dynamism and uncertainty of modern processes can be taken into account through the realization of a number of legal and social experiments before implementing new norms. In addition, this measure will avoid serious consequences caused by the complementarity of labor market institutions, when single changes lead to unexpected results.

Conclusion

The research results confirm the thesis about the wide prevalence of precarization indicators among Russian youth. The share of the sustainably employed young people is only 8%, which together with the transition group gives about 21%. All the rest are involved in precarious labor relations to a greater or lesser extent. At the same time, a high level of education and ICT skills, as well as engagement in skilled labor, will help to reduce the concentration of precarization indicators. This is particularly evident in the case of digital competencies, the presence of which within the same educational or qualification group leads to an increase in the share of sustainably employed. On this basis, it follows that the stability of young workers’ position depends both on the traditional characteristics of job seekers and on the ability to use modern technologies in the performance of job duties. At the same time, developed qualities do not guarantee protection from unemployment as an extreme form of precarization, but in this case the chances of successful employment are significantly increased.

In the analysis, we emphasize the importance of rapid transition to stable employment, as the depth of precarization penetration negatively affects the standard of living. For instance, young people from the least and low-income strata are characterized by the greatest number of signs of instability, the concentration of which begins decreasing only when household expenditures increase to 1–2 sizes of the consumer basket of subsistence minimum. This statement allows concluding that the boundary between income and consumption is sensitive for low-income young people, although this pattern is not observed among the least well-off ones because of insignificant differences in wealth. The situation is similar in wealthier groups, primarily those with per capita incomes above 3.1 subsistence minimum, where, in addition to high earnings, jobs offer a fundamentally new level of social security. However, even here young workers with precarious labor relations are not rare. In turn, unemployment, as an extreme form of precarization, has no pronounced specifics in terms of income groups. Affluent strata are naturally less likely to be in the process of job search.

Based on the above, we can conclude that with increasing concentration of precarization indicators there is a marked deterioration in the standard of living. In this respect, we should point out that there are young people with a high level of education and ICT skills who are engaged in skilled labor. Of course, in some cases it is possible to remain part of the parental household for a while or to receive financial assistance from relatives, but a certain standard of consumption is usually achieved through a combination of these characteristics. Ultimately, the developed professional and digital competencies of young people become a prerequisite for rapid transit from school to stable employment.

Along with the substantiation of proposals to mitigate the threats of precarization to the quality of employment and the standard of living of young people, the empirical results have a specific theoretical and practical value, since they can be useful, on the one hand, for developing ideas about the phenomenon of instability in the sphere of social and labor relations, on the other hand, for improving federal and regional policies to ensure a rapid transition of graduates of professional educational organizations from study to stable employment. Focusing on young workers in this respect will help to avoid the cumulative effects of precarization, which are much more harmful with age. Prospects for further research include studying educational and professional trajectories that lead to a deterioration in the quality of working life.

Список литературы The impact of precarization on the standard of living and employment situation of Russian youth

- Bessant J., Farthing R., Watts B. (2017). The Precarious Generation. A Political Economy of Young People. London: Routledge.

- Bobkov V.N. (Ed.). (2019). Neustoichivaya zanyatost’ v Rossiiskoi Federatsii: teoriya i metodologiya vyyavleniya, otsenivanie i vektor sokrashcheniya [Unsustainable Employment in the Russian Federation: Theory and Methodology of Identification, Estimation and Vector of Reduction]. Moscow: KnoRus.

- Bobkov V.N., Litvinyuk A.A. (Eds.). (2016). Rossiiskaya molodezh’ na rynke truda: ekonomicheskaya aktivnost’ i problemy trudoustroistva v megapolise [Russian Youth in the Labor Market: Economic Activity and Employment Problems in the Megacity]. Moscow: RUSAINS.

- Bobkov V.N., Loktyukhina N.V., Shamaeva E.F. (Eds.). (2022). Uroven’ i kachestvo zhizni naseleniya Rossii: ot real’nosti k proektirovaniyu budushchego [Living Standards and Quality of Life of the Russian Population: From Reality to Projecting the Future]. Moscow: FNISTs RAN

- Bobkov V.N., Odintsova E.V., Popov A.V. et al. (2023). Vliyanie prekarizatsii na kachestvo zanyatosti i uroven’ zhizni pokolennykh grupp ekonomicheski aktivnogo naseleniya [Impact of Precarization on the Quality of Employment and Living Standards of Generational Groups of the Economically Active Population]. Izhevsk: Shelest.

- Bobkov V.N., Odintsova E.V., Ivanova T.V. et al. (2022a). Significant indicators of precarious employment and their priority. Uroven’ zhizni naseleniya regionov Rossii=Living Standards of the Population in the Regions of Russia, 18(4), 502–520. DOI: 10.19181/lsprr.2022.18.4.7 (in Russian).

- Bobkov V.N., Odintsova E.V., Shichkin I.A. (2022b). The impact of professional skills in the use of information and communication technologies on the income from employment: Generational differentiation. Rossiiskii ekonomicheskii zhurnal=Russian Economic Journal, 4, 93–113. DOI: 10.33983/0130-9757-2022-4-93-113 (in Russian).

- Bohle P., Quinlan M., Kennedy D. et al. (2004). Working hours, work-life conflict and health in precarious and “permanent” employment. Revista de saude publica, 38, 19–25. DOI: 10.1590/s0034-89102004000700004

- Bone K.D. (2019). “I don’t want to be a vagrant for the rest of my life”: Young peoples’ experiences of precarious work as a “continuous present”. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(9), 1218–1237. DOI: 10.1080/13676261.2019.1570097

- Cassells R., Duncan A., Mavisakalyan A. et al. (2018). Future of Work in Australia. Preparing for Tomorrow’s World. Perth: Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre.

- Chan S., Tweedie D. (2015). Precarious work and reproductive insecurity. Social Alternatives, 34(4), 8–13.

- Choonara J. (2020). The precarious concept of precarity. Review of Radical Political Economics, 52(3), 427–446. DOI: 10.1177/0486613420920427

- Cranford C.J., Vosko L.F., Zukewich N. (2003). Precarious employment in the Canadian labour market: A statistical portrait. Just Labour, 3. DOI: 10.25071/1705-1436.164

- Gasper D. (2007). Human well-being: Concepts and conceptualizations. In: McGillivray M. (Ed.) Human Well-Being. Studies in Development Economics and Policy. Palgrave Macmillan, London. DOI: 10.1057/9780230625600_2

- Giltman M.A., Merzlyakova A.Yu., Antosik L.V. (2022). Exit from registered unemployment: Estimating the impact of individual characteristics. Voprosy gosudarstvennogo i munitsipal’nogo upravleniya=Public Administration Issues, 1, 193–219. DOI: 10.17323/1999-5431-2022-0-1-193-219 (in Russian).

- Jetha A., Martin Ginis K.A., Ibrahim S. et al. (2020). The working disadvantaged: The role of age, job tenure and disability in pre-carious work. BMC Public Health, 20. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-020-09938-1

- Khusainov B., Alzhanova F. (2017). Employment precarization as a global challenge: Measuring and assessing the impact on Kazakhstan’s development. Kazakhskii ekonomicheskii vestnik=Kazakh Economic Review, 2(28), 2–13 (in Russian).

- Kuchenkova A.V. (2022). Employment precarization and the subjective well-being of employees in different age groups. Sotsiologicheskii zhurnal=Sociological Journal, 28(1), 101–120. DOI: 10.19181/socjour.2022.28.1.8840 (in Russian).

- Kuchenkova A.V., Kolosova E.A. (2018). Differentiation of workers by features of precarious employment. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: Ekonomicheskie i sotsial’nye peremeny=Monitoring of Public Opinion: Economic and Social Changes, 3, 288–305. DOI: 10.14515/monitoring.2018.3.15 (in Russian).

- Kurennoy A.M. (2022). The need for urgent creation new Labour Code: Idea fix? Ezhegodnik trudovogo prava=Russian Journal of Labour & Law, 10, 40–52 (in Russian).

- Lodovici M.S., Semenza R. (Eds.). (2012). Precarious Work and High-Skilled Youth in Europe. Milan: FrancoAngeli.

- Melges F., Calarge T.C.C., Benini E.G. et al. (2022). The new precarization of work: A conceptual map. Organ. Soc., 29(103), 638–666. DOI: 10.1590/1984-92302022v29n0032en

- Miguel Carmo R., Cantante F., de Almeida Alves N. (2014). Time projections: Youth and precarious employment. Time & Society, 23(3), 337–357. DOI: 10.1177/0961463X14549505

- Mrozowicki A., Trappmann V. (2021). Precarity as a biographical problem? Young workers living with precarity in Germany and Poland. Work, Employment and Society, 35(2), 221–238. DOI: 10.1177/0950017020936898

- Odegov Yu.G., Babynina L.S. (2018). Precarious employment as a possible factor behind the use of youth labor force potential in Russia. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: Ekonomicheskie i sotsial’nye peremeny=Monitoring of Public Opinion: Economic and Social Changes, 4, 386–409. DOI: 10.14515/monitoring.2018.4.20 (in Russian).

- Popov A.V., Soloveva T.S. (2020). Employment precarization: An analysis of academic discourse on the essence and ways of measuring. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya=Sociological Studies, 9, 103–113. DOI: 10.31857/S013216250009618-2 (in Russian).

- Popov A.V., Soloveva T.S. (2023). Employment prospects for the population of Russia along the center-periphery axis (the case of Vologda Region). Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya=Sociological Studies, 8, 47–59. DOI: 10.31857/S013216250027366-5 (in Russian).

- Shehu E., Nilsson B. (2014). Informal Employment among Youth: Evidence from 20 School-to-Work Transition Surveys. Geneva: ILO.

- Shkaratan O.I., Karacharovskiy V.V., Gasiukova E.N. (2015). Precariat: Theory and empirical analysis (polls in Russia, 1994–2013 data). Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya=Sociological Studies, 12, 99–110 (in Russian).

- Sršen A., Dizdarevič S. (2014). Precariousness among young people and student population in the Czech Republic. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(21), 161–168.

- Standing G. (2011). The Precariat. The New Dangerous Class. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Stuth S., Jahn K. (2020). Young, successful, precarious? Precariousness at the entry stage of employment careers in Germany. Journal of Youth Studies, 23(6), 702–725. DOI: 10.1080/13676261.2019.1636945

- Toshchenko Zh.T. (Ed.). (2020). Prekariat: stanovlenie novogo klassa [Precariat: The Emergence of a New Class]. Moscow: Tsentr sotsial’nogo prognozirovaniya i marketinga.

- Umicevic A., Arzenšek A., Franca V. (2021). Precarious work and mental health among young adults: A vicious circle? Managing Global Transitions, 19(3), 227–247. DOI: 10.26493/1854-6935.19.227-247