The institutional aspect of German family policy: lessons for Russia in the context of national projects

Автор: Kapoguzov Evgeny A., Chupin Roman I., Kharlamova Maria S.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Global experience

Статья в выпуске: 6 т.14, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Breaking out of a demographic trap is a priority of national policy in Russia. To achieve this goal, the national project “Demography” was adopted. The purpose of our study is to review current trends in European family policy in the case of Germany and to identify opportunities for applying foreign experience in improving the provision of institutional support to family policy in the Russian Federation. In our work, we use methods of institutional and statistical analysis. Unlike the studies of other authors, our own assessment of the effectiveness and sufficiency of expensive measures being developed in Russia is based on an institutional analysis that we conduct so as to reveal trends in European family policy on the example of Germany, which is characterized by an institutional logic of family policy similar to Russia. Family policy in Germany is based on increasing public spending on the creation of a developed system of social infrastructure. Both countries focus on increasing the birth rate and the development of social infrastructure that allows women not to abandon their career; but it is assumed that for Russia, the relevant implications will be more significant. As a result of accelerated construction of kindergartens in major agglomerations of Germany, an increase in the birth rate is demonstrated. However, this effect is mostly caused by the migration wave of 2015, while immigrants are insensitive to the measures being implemented. In addition, this leads to an outflow of population from other regions. The significance of the article lies in the fact that the consideration of the contradictions between various courses of family policy in Germany over the past 20 years has revealed the possibilities of using foreign experience in improving the institutional support of family policy in Russia. Based on the analysis we carried out, and taking into consideration the experience of Germany, we propose recommendations in the field of socioeconomic policy that can specify the parameters of the national project “Demography” in terms of taking into account regional demographic situation.

Family policy, birth rates, institutional birth control, discrete institutional alternatives, national project

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147236303

IDR: 147236303 | УДК: 314.07:314.5.063 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2021.6.78.16

Текст научной статьи The institutional aspect of German family policy: lessons for Russia in the context of national projects

One of the key strategic goals of Russia’s national development, announced by the President of the Russian Federation during his Address to the Federal Assembly in 2020, is to get out of the “demographic trap”1. For its implementation, the Russian Federation has adopted the national project “Demography”, designed to ensure “saving the population” and give a long-term impetus to economic development through investments in human capital. But, according to V.K. Faltsman: “The national project “Demography” provides for an expensive set of measures to stimulate the birth rate and the duration of active life in the period through to 2024. But only these measures are not enough to contain depopulation” [1, p. 7].

For instance, already in October 2020, the Government of the Russian Federation has updated the population forecast. According to it, by 2024, the number of Russians is expected to decrease by 1.2 million people2. Such a decline, according to Russian scientists, has both a purely demographic [2] and an institutional basis [3]. The latter was defined in January 2021 by Vladimir Putin at the World Economic Forum in Davos as a “value crisis”, which turns into negative demographic consequences, due to which humanity risks losing entire civilizational and cultural continents”3.

Currently, non-traditional family relationships are indeed gaining popularity in the world; there is a gradual deinstitutionalization of marriage [4]. Broadly speaking, deinstitutionalization means the stratification of an institution [5], in which the erosion of norms and rules is fixed in terms of their impact on various social strata. The deinstitutionalization of marriage in European countries has led to the fact that the “old” forms of family relations have lost their dominant positions and uncompromising directives.

In this regard, the Russian Federation remains a “reserve” of old family values [6], but continues experiencing threats of depopulation4. The pandemic of the new coronavirus infection COVID-19 has exposed the problems of the family institute in Russia especially acutely. As O.G. Isupova notes, in the light of a sharp change in the “daily routine”, Russian families may face many problems, which can aggravate the already unstable demographic situation [7].

Against the background of familiar and new challenges to the reproduction of the Russian population, the authorities are converting the institution of marriage in constitutional amendments, taking unprecedented measures in recent history to support families and fertility [8]. At the same time, in a number of European countries with demographic problems similar to Russia, many of the measures, proposed by the President and the Government of the Russian Federation to support marriage and fertility, have already been implemented, and have led to contradictory results.

For example, in Germany, where family care is laid down in Article 6.1 of the Constitution, since the beginning of the 21st century, an almost complete list of family policy measures, proposed by the Russian government, has been implemented [9], but already in 2019 there was a significant decrease in the fertility rate (the increase was only 0.6%). Also in 2020, there was a decline in the number of working-age population by 0.9%, in particular, in Thuringia, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, every fifth employee was over 55 years old5.

The purpose of the research is to review the current trends of European family policy in the case of Germany, and identify opportunities to use foreign experience in improving the institutional support of family policy in Russia. Based on this goal, the objectives of the study are: 1) to review the specifics of the German version of implementing family policy in the context of the household economic theory from the standpoint of institutional strengthening of infrastructural and financial support for families with children; 2) to consider the results of the demographic transition in German family policy; 3) to disclose contradictions and possible lessons of the German experience for Russian family policy.

Methodological foundations of institutional analysis of family policy

The fundamental foundations of the family policy are based on two concepts existing within the framework of the new economics of the family: traditional (Beckerian [10]) and transactional approaches [11].

The traditional approach does not look inside the “black box” of intra-family relations allowing for the absolute rationality of demographic behavior.

In this context, the family policy should not restrict the freedoms of the marriage market, as well as the households’ rights to childlessness. With the transactional approach, in turn, family and marriage become an institutionalized form of a “relational” contract with characteristic features: regular interaction of partners in marriage and the presence of family capital (marital-specific capital), which reduces the risks of divorce. Therefore, the transactional approach has more explanatory power, allows considering the transformation processes of family relations [12] and the emergence, in addition to traditional marital relations, of marriage-like unions (cohabitation or “civil marriages”) [13].

Many of these forms find their place in the institutional environment of European countries. Thus, the “value crisis” in recent history is associated with the emergence of new discrete institutional alternatives [14] to family policy. If in Russia and a number of Eastern European states there are no marriage rights and obligations, established by law, then in France and Germany such unions have received a legal status. In particular, in Germany, since 2005, the norm of the Social Code (Zweite Buch Sozialgesetzbuch) has been in force, according to which members of marriage-like unions forming “consumer communities” (Bedarfsgemeinschaft) can enter into partnership agreements on the use of property. In terms of this, the main alternative to the family policy is associated with “defamilization” [15].

One of the key signs of defamilization was the adoption in 2008 of a special law on demographic support — Kinderforderungsgesetz 2008 [16; 17], which aims to open women’s access to the labor market through the development of various organizational forms of child rearing and caring for them (designated as “Kita”). We are talking primarily about investments in the construction of kindergartens (Kindergarten) and the development of other institutional forms that implement the functions of supervision (Aufpassung) and care (Betreuung) [18]

for children. For instance, according to the German statistical office, 93% of children aged 3 to 5 years receive some kind of supervision in Kita, and the number of such structures is 56,7006.

According to the data of the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, senior citizens, women and youth of Germany, in the period from 2007 to 2014, about 5.4 billion euros were financed for the construction and maintenance of child care infrastructure [19], which led to the creation of 780 thousand places in kindergartens [20, p. 92].

Despite a number of efforts to expand the role of “fatherhood” in the upbringing of children, as well as the existence of legislative and institutional incentives to participate in the upbringing of children, in Germany, there are not enough conditions that let men combine fatherhood and career. According to a study by C. Zerle and I. Krok, 68% of young fathers are still unable to take advantage of parental leave due to difficulties with reducing the number of working hours, although the willingness not only to bear financial responsibility for the family well-being, but also to pay more attention to communicating with children is rated quite high [21].

From the point of view of the “Eurosceptics”, the neoliberal-feminist concept of “an educated and career-oriented woman with great employment”, which opposes “the image of a woman as a mother and keeper of the hearth”, is negative for high-quality family policy: it leads to the fact that young girls begin looking at children as a “dead weight” that hinders career growth. This is explained, in particular, by the reaction of “Eurosceptics” to the transformation of family policy in Germany: from a conservative model to a more sustainability-oriented and inclusive (in the “Scandinavian style”), which is characterized as “egalitarian and gender-sensitive”.

As a result of the “value crisis”, mother’s age at the birth of the first child is constantly increasing; every fifth woman refuses to have children; the number of young children brought up with minimal mother’s participation is constantly growing; the number of single mothers is increasing; large families are socially unprotected, parents of newborn children are forced to take “an additional burden to feed the family” [22, p. 54].

Despite the signs of the “value crisis” in Germany [23], family policy, according to German scientists, can be considered as real practices of supporting the traditional family [24]. For example, structural alternatives to family policy in Germany may be associated with “refamilization”, when a woman implements the traditional priority family function of a mother associated with the principle of “three K” (Kinder, Kuche, Kirche — children, kitchen, church), receiving through social policy measures the opportunity to engage in a household in a market environment and provide effective socialization for children. Also, we should note that the emphasis on “child production” contradicts the value-cultural attitudes and practices of developed countries [25]. This casts doubt on the possibility of realizing the goal of increasing the total birth rates, creating opportunities only to maintain them in certain countries, in particular France, Sweden, Finland and others [26, p. 119].

The results of the analysis of the demographic change in Germany family policy

According to the Esping-Andersen approach, variations of family policy, as a component of variations of welfare states, are divided into three types: liberal, conservative and social democratic (Scandinavian) [27]. M. Bujard noted: “Family policy for welfare states will play a key role in the next decade, since its instruments such as child benefits (Kindergeld), benefits for parents (Elterngeld), infrastructural measures (Kinder-betreuung) simultaneously support different goals, namely the fight against poverty, education, justice, participation in the labor market and birth rate growth” [25].

The discussion about the complementarity of the goals of family policy in a number of European countries indicates the inconsistency of the results. Some authors adhere to a skeptical position [28], others note a positive relationship between family policy and childbearing [29]; a number of authors [24; 30] testify to the ambiguity of such relationships. In our opinion, in addition to the factors of contributing the “value crisis” affecting the falling birth rates in Western countries, we can note the specific factors that have arisen in the last decade that cause additional difficulties in implementing family policy, in particular, refamilization, political and migration factors.

Refamilization is primarily explained by the negative dynamics of the indicators of the total fertility rates (TFR) over the previous 50 years. The relationship between family policy and the TFR allowed talking about “demographic change”, in which the largest increase in the birth rate is typical of large cities. This conclusion contradicts the traditional notions of a high birth rate in rural areas in relation to urban agglomerations. Its highest level is demonstrated by Frankfurt am Main, Munich and Berlin, where the TFR values are higher than the national average (amounting to 22.8 children per 1000 women7). The birth rates of East German Leipzig are so high that they allow talking about a “new style” of urban life, where children have also become natural for urban identity8.

The conservative family policy of the right-wing political forces is connected with two circumstances. First, we are talking about the growing Islamic immigration to Europe. The number of Muslims in the period from 2011 to the end of 2016 increased by 1.2 million people and amounted to 4.4 to 4.7 million people, or approximately 5.4 to 5.7% of the German population. According to demographers’ estimates, which are given in the documents of the political party “Alternative for Germany” (AfD), by 2060 the population of the country will decrease from 81 to 65–70 million people. Second, the concern is connected with the understanding that the indigenous population of the continent at the moment can hardly compete with the Muslim community in terms of the birth rate even on its own territory. So, in modern Europe (EU, Norway, Switzerland), the proportion of Muslims is about 4.9% of the population. By 2050, it may increase to 11%, and in Germany the number of Muslims may reach 16–18 million people and lead to the existence of a “parallel” Muslim society [31, p. 113].

This increase in the share of the Muslim population is explained by two circumstances: a) the relative youth of the average age of Muslims (31 years compared to 47 years for the non-Muslim population); b) the difference in total fertility rates between “traditional” German and Muslim families: on average, the ratio of coefficients is 1.4 to 1.9 in favor of German residents of Muslim origin9.

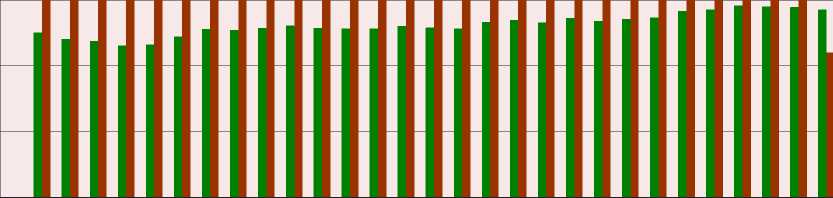

The dynamics of total birth rates in Germany is shown in Figure 1 .

This situation is typical for many other Western European countries. For example, in the UK, the ratio gap in birth rates is more noticeable: the average Muslim woman has 2.9 children at the fertile age, and the British woman has 1.8.

2,5

1,5

0,5

Figure 1. Dynamics of total birth rates in Germany for the indigenous population and immigrants in 1991–2019, births per woman of fertile age

■ Indigenous population ■ Immigrants

According to: Federal Statistical Office data, Wiesbaden 2020.

Estimated differences in birth rates between the conventionally Islamic and traditionally European part of the German population contribute to the aggravation of the ideological contradictions of the “Eurosceptics” with the policy of multiculturalism, which has become widespread among the neoliberal part of the German socio-political elite.

It is worth noting that the measures of the 2008 law did not fully manifest themselves also due to the financial and economic crisis of 2008–2009, which primarily affected youth unemployment and, thereby, the life plans of some households. In general, according to M. Klein and his co-authors, it is still too early to state unequivocally “the causal relationship between the turn in family policy and the demographic turn”. Moreover, birth rates in Germany are still lower than in other European countries, among which the UK stands out as the leader, where the number of births per thousand inhabitants ranged from 11.5 to 13 from 2000 to 2014 (in Germany during the same period, the value was in the range from 8 to 9 newborns per thousand inhabitants) [17, p. 689].

Can Russia learn a lesson?

Thus, as the article shows, the existing mechanisms of family policy in Germany poorly correlate with the mechanisms of institutional strengthening of the traditional family and are largely determined by exogenous factors. The German authorities declare support for traditional family values, but at the same time, implement a costly gender-sensitive model of family policy, aimed at creating favorable conditions for marriagelike unions. Moreover, the support of traditional families demonstrating a high birth rate has faded into the background. In view of this, the increase in government spending on the creation of a developed system of social infrastructure Kita does not lead to demographic growth and is political in nature.

The actual drivers of natural population growth in Germany today are migration processes and a high birth rate among the Islamic population.

However, focusing on the overall increase in total fertility rates leads to the conclusion of a “demographic transition”, the characteristic of which is the relative increase in fertility in urban agglomerations in relation to rural areas. This contradicts scientifically established patterns causing the German authorities to lose sight of the real demographic situation.

Russia repeats the German mistake with regard to the lack of consideration of regional specifics and orientation toward increasing quantitative indicators of fertility. The target indicators, provided for in the national project “Demography”, assume an increase in total fertility rates. However, the documents do not take into account the institutional features of birth control in the entities of the Russian Federation, as well as interregional migration processes. At the same time, as the analysis, carried out by the authors in another article, shows, in response to the “Beckerian” family reacting to the economic incentives of demographic policy, it is advantageous for the state from a pro-natalist position to bet on increasing income and reducing poverty for all types of households; in the case of the predominance of traditional families, to focus on values at the birth of children [32].

The creation of the social infrastructure, envisaged by the national project in the regions of the Russian Federation, will not be able to eliminate differences in the socio-economic conditions of the birth and upbringing of children, which is manifested, in particular, in significant differences in measures to support families with children in the Russian regions [33]. For instance, the creation of kindergartens and their maintenance in the Russian Federation refers to issues of local importance, which implies inequality in the opportunities of rural territories and urban agglomerations. This basis is an important factor in strengthening intramigration processes. As a result, there are demographic risks similar to Germany of depopulation of individual territories, as well as an increase in the birth rate in large agglomerations. In turn, the growth of urban agglomerations leads to the complication of the marriage market and the stratification of the institution of marriage under the influence of the intersection of many cultural and value norms. In such conditions, modern forms of family relations are spreading offering simpler and faster ways to create and build a family that differs from the traditional one. Consequently, the Russian “reserve” of traditional family values risks getting provincial status according to the German scenario.

Summing up, we should note: in our opinion, from an institutional point of view, in order to increase the effectiveness of family policy, both in the direction of increasing the Russians’ incomes and reducing poverty, and increasing the birth rate, a “fine-tuning” of regional demographic development programs is necessary, since at the moment there is virtually no regional policy [32]. At the same time, development policy should not be limited exclusively to measures to stimulate fertility (including without taking into account the marriage factor), the ambiguity of which is emphasized in modern studies [34], a broader comprehensive view of demographic processes is required, consisting in a greater targeting of support for families with children from the point of view of human capital development in family households [35]. In this regard, the scientific support of family policy from the position of an evidence-based approach is seen as promising, which allows identifying both the shortcomings of the existing policy and justifying potential management decisions through the use of tools such as “big data” and machine learning.

Список литературы The institutional aspect of German family policy: lessons for Russia in the context of national projects

- Faltsman V.K. Russia: Growth factors in the framework of the global economy. Sovremennaya Evropa=Contemporary Europe, 2020, no. 1, pp. 5–13 (in Russian).

- Rybakovsky O.L. Russian population reproduction: Challenges, trends, factors and possible results by 2024. Narodonaselenie=Population, 2020, no. 1 (23), pp. 53–66 (in Russian).

- Kapoguzov E.A., Chupin R.I., Kharlamova M.S. Russian constitutional conversion in the context of deinstitutionalization of marriage in the USA. Journal of Institutional Studies, 2020, no. 2 (12), pp. 86–99 (in Russian).

- Kapoguzov E.A., Chupin R.I., Kharlamova M.S. Institutionalized arenas of marriage games. Journal of Institutional Studies, 2019, no. 4 (11), pp. 26–39 (in Russian).

- Cherlin A.J. The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 2004, no. 4 (66), рp. 848–861.

- Mironova A.A., Prokofieva L.M. Family and household in Russia: The demographic aspect. Demograficheskoe obozrenie=Demographic Review, 2018, no. 2 (5), pp. 103–121 (in Russian).

- Isupova O.H. New problems of Russian families in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Population and Economics, 2020, no. 2(4), рp. 81–83.

- Kapoguzov E.A., Chupin R.I. Economic mechanisms of family policy in Russia in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Voprosy regulirovaniya ekonomiki=Journal of Economic Regulation, 2021, no. 12 (3), pp. 26–43. DOI: 10.17835/2078-5429.2021.12.3.026-043 (in Russian).

- Demkina E.V. Family and child support programs in Germany. Science of Europe, 2019, no. 35, pp. 72–75 (in Russian).

- Becker G.S. A Treatise on the Family. London: Harvard University Press, 1993. 304 p.

- Pollak R.A. A transactional cost approach to families and households. Journal of Economic Literature, 1985, no. 2 (23), рp. 581–605.

- Cherlin A.J. Degrees of change: An assessment of the deinstitutionalization of marriage thesis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 2020, no. 1 (82), рp. 62–80.

- Bumpass L.L., Raley R.K. Redefining single-parent families: Cohabitation and changing family reality. Demography, 1995, no. 1 (32), рp. 97–109.

- Shastitko A.E. Choosing between discrete institutional alternatives: What do we compare? Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost’=Social Science and Contemporary World, 2016, no. 4, pp. 134–145 (in Russian).

- Noskova A.V. Family policies in Europe: Evolving models, discourses and practices. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya=Sociological Studies, 2014, no. 5, pp. 56–67 (in Russian).

- Del Boca D., Flinn C., Wiswall M. Household choices and child development. The Review of Economic Studies, 2014, no. 1 (81), рp. 137–185.

- Klein M., Weirowski T., Künkele R. Geburtenwende in Deutschland – was ist dran und was sind die Ursachen? Wirtschaftsdienst, 2016, vol. 96, рp. 682–689.

- Huesken K. Kita vor Ort: Betreuungsatlas auf Ebene der Jugendamtsbezirke 2010. Munich: Deutsches Jugendinstitut eV Abteilung Kinder und Kindertagesbetreuung, 2011. 29 p.

- BMFSFJ Erster bis Vierter Zwischenbericht zur Evaluation des Kinderförderungsgesetzes, Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. Berlin: 2013. 49 р.

- Sazonova P.V. Seeking a balance: The transformation of gender as a response to the shifts in the state family policy (a case of Germany). Vestnik Tomskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta=Tomsk State University Journal, 2015, no. 400, pp. 88–99 (in Russian).

- Zerle C., Krok I. Fathers put to the test. Family experiment. In: Deutsches Jugendinstitut Bulletin. München, 2010. 24 р.

- Gribovskii V.S. German, Austrian and Swiss eurosceptics’ views on family issues. Nauchno-analiticheskii vestnik Instituta Evropy RAN=Scientific and Analytical Herald of the Institute of Europe RAS, 2019, no. 3(9), pp. 54–58 (in Russian).

- Noskova A.V. Choice as a new principle of family policy in the context of pluralization of family practices. Materialy Afanas’evskikh chtenii=Materials of the Afanasiev Readings, 2015, no. 13, pp. 307–312 (in Russian).

- Kaufmann F-X. Schrumpfende Gesellschaft. Vom Bevölkerungsrückgang und seinen Folgen. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 2005. 270 p.

- Bujard M. Familienpolitik und Geburtenrate: Ein internationaler Vergleich, Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung. Wiesbaden, 2011. 46 р.

- Noskova A.V. New approaches in family policy in the context of changing social realities. Sotsial’naya politika i sotsiologiya=Social Policy and Sociology, 2016, no. 5 (118), pp. 117–126 (in Russian).

- Esping-Andersen G. Why We Need a New Welfare State. Oxford University Press, 2002. 244 p.

- Höhn Ch., Ette A., Ruckdeschel K. Kinderwünsche in Deutschland. Konsequenzen für eine nachhaltige Familienpolitik. Stuttgart: Robert Bosch Stiftung & BIB, 2006. 86 р.

- Rürup B., Schmidt R. Nachhaltige Familienpolitik im Interesse einer aktiven Bevölkerungspolitik. Berlin: BMFSFJ, 2003. 66 р.

- Gauthier A.H. The impact of family policies on fertility in industrialized countries: A review of the literature. Population Research and Policy Review, 2007, no. 3 (26), рp. 323–346.

- Andreeva L.A. Islamization of Germany: “Parallel” Muslim society vs. secular state. Sovremennaya Evropa=Contemporary Europe, 2019, no. 5, pp. 110–121 (in Russian).

- Kapoguzov E.A., Chupin R.I., Kharlamova M.S. Assessment of family policy achievements in income increase and poverty decrease in Russia. Voprosy upravleniya=Management Issues, 2021, no. 4, pp. 108–122 (in Russian).

- Kapoguzov E.A., Chupin R.I., Kharlamova M.S. Family policy narratives in Russia: Focus on regions. Journal of Economic Regulation, 2020, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 6–20 (in Russian).

- Latov Yu.V. (2021). Human capital growth contra birth rate growth. Journal of Institutional Studies, 2021, vol. 13 (2), pp. 82–99 (in Russian).

- Kapoguzov E.A., Chupin R.I. Effectiveness of family policy in Russia: Evidence-based approach. Terra Economicus, 2021, no. 19 (3), pp. 20–36 (in Russian).