The president's unfinished work. Public administration system is not ready to function without manual control

Автор: Ilyin Vladimir Aleksandrovich

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: From the chief editor

Статья в выпуске: 5 (53) т.10, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223990

IDR: 147223990 | УДК: 338.24 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2017.5.53.1

Текст статьи The president's unfinished work. Public administration system is not ready to function without manual control

The year 2017 marks the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution and a “final lap” before the 2018 presidential election. Both events bring to the fore the agenda of public administration efficiency and the quality of the ruling elites – these are fundamental, system-wide issues that affect the standard of living of every Russian citizen, smooth operation of Russia’s socio-economic system, and Russia’s national security on a global scale.

Many experts think that the events of the October Revolution of 1917 should be considered from an objective historical standpoint and they try to avoid direct analogies with present time. “We need to look at those events from all sides, to rise above the struggle of their participants; we must look back upon the winners and victims fairly and impartially”1. However, without the vision of historical parallels it is impossible to learn the lessons of the past and, consequently, prevent hasty steps in the future, which, as Russian historical experience proves, can have disastrous consequences. “Any historical research allows us to make forecasts about the future; although, as a rule, it teaches us nothing. People make mistakes all the same...”2

M. Rostovskii: “Neither at the beginning nor at the end of the 20th century was there any force in Russia that would be interested in the preservation and development of the state. This force emerged and was victorious when the country was getting out of an acute political crisis. But on the point of entry into the crisis it was nonexistent. In 1917, as well as in 1991, private interests: group, individual, parochial, etc., dominated The problem of Russia – in February 1917 and in other moments of its history – consisted in a lack of the mechanism that would bring together the will of different groups in a single national interest, the national will”3.

From1 this point of view, it should be noted that Nicholas II, according to some historians, did not possess those necessary qualities that would allow him to “formulate” an adequate response to internal challenges that Russia was facing due to objective historical reasons; nor could he deal with external challenges that England and the United States, the leading world powers of that time, had in store for

A. Samsonov: “Nicholas II did not have the iron will of his father Alexander III and great-grandfather Nicholas I to counter a sophisticated and insidious enemy (the “civilized West”), as well as the abilities and ruthlessness of Peter the Great to implement radical transformations in Russia so as to ensure that it survived in a world war, won it and emerged as a new Russia. And without radical transformation the old Russia of the Romanov dynasty could not survive. Contradictions lying at its foundation were too profound. During the three centuries of its existence, the margin of safety of the “White Empire” was exhausted”4.

Russia. His inability to govern the country in manual mode by keeping questions of foreign policy under his personal control and nipping in the bud the earliest symptoms of the coming Revolution became one of the main factors that triggered the events of 1917.

The situation was the same in 1991, the year when the Soviet Union collapsed. And here again we see the presence of Western interests and the failure of the top state official (Mikhail Gorbachev) to demonstrate his political will and make tough political decisions to preserve national sovereignty.

Zh.T. Toshchenko: “Gorbachev turned out to be at the peak of a historic challenge of the time, but failed to prove himself as the creator, the maker who offered the society new ideas and a new vision of the future. He did not possess strategic thinking, did not understand the essence of the situation and trends of development of the processes; he was unprincipled, indecisive, constantly late in making decisions”5.

But2 there were people with quite different (one might even say opposite) personal traits and, accordingly, style of governance, the people who in times of crisis found the strength to take responsibility for solving key national security issues in foreign policy and internal socio-economic life. Thus, in spite of being criticized for their political methods, Ivan the Terrible and Joseph Stalin, each in his own time, managed to prevent the country from collapsing and to defeat external enemies.

Thus, the style of governance, in which there is always a specific person at the helm, is one of the key factors determining the course of Russian history. And the events of the 20th century indicate that at its turning points the country faces a need for manual mode of public administration that requires the national leader to possess the qualities required of an individual that is capable of taking personal responsibility for key decisions in domestic and foreign policy.

In all the four cases mentioned above, the national leader had to respond at least to three kinds of challenges simultaneously: external military threats, citizens’ discontent with the dynamics of the standard of living and quality of life, and behind-the-scenes politics inside the government that in fact was preparing the ground for potential collapse of Russian statehood. Russia could get out of such situations with dignity only when its national leader “engaged” manual control mode and supervised personally the matters of internal and foreign policy, finding the strength to make tough decisions in the interests of national security.

Does manual control mode for the system of administration still exist today? Is it necessary? And can there be any alternatives? These questions become more and more relevant with the approach of a new political cycle, and if Vladimir Putin runs for presidency and wins the 2018 election, it will be his last six-year term in office6.

It should be noted that it was President Putin himself who used the term “manual control” in this context for the first time in 2007, the year when he delivered his famous Munich Speech that in essence determined the main principles of Russia’s foreign policy for decades to come. In subsequent years, the President has more than once used the term when referring to the Government’s failures to execute his decrees. Although at the end of this year’s direct live TV phone-in Vladimir Putin spoke more cautiously: “I wouldn’t say that everything is done in manual control mode or with the help of a hands-on approach; though we sometimes have to deal with issues that require special attention, including that from the Government and President”7.

Vladimir Putin: “We have to keep everything under control. If necessary, though some may not like it, but in this case, it makes sense, we have to assume a ‘hands-on’ approach. In this situation, there is nothing shameful about it...Today I would like to ask you to use this approach again, so it is clear who is responsible for what, and what the situation is like at major strategic facilities, how it affects employment, how social issues are being resolved at enterprises and what is going on at single-industry towns. All this needs to find reflection in corresponding action plans that have to be very detailed with a precise indication of the individuals responsible”8.

According to experts, the “manual control of the state” metaphor appeared by analogy with controlling an aircraft. “An aircraft usually goes in automatic control mode, but if the system fails, there is an emergency and the pilot switches to manual control”9.

The analogy with an aircraft is not accidental, since the state, which in all its historical periods was the main subject to initiate national development (in the broad sense of the word: social, economic, political, cultural, etc.), sometimes becomes his own worst enemy. It happens when the country’s internal contradictions reach their climax, “reset to zero”, and a single dominant political force comes to power; and then the ruling elite becomes incapable of self-restraint and cannot reach consensus in order to preserve the country. The system stops working automatically, and there is a need to switch to “manual control” mode.

Within the political elite there emerge some groups whose representatives begin to fight for power. And while specific individuals in the ruling elite are fighting for the expansion of spheres of influence, they perform their duties (governance of the country in accordance with national interests, maintaining national security, and strengthening national sovereignty) residually, which in the first place affects national interests and the interests of national security.

That was how the Revolution of 1917 was “forged” and that was how the Soviet era was collapsing.

Today, political maneuverings take place at all levels of the power hierarchy. It is demonstrated by the data of “Politburo 2.0”

M. Rostovskii: “For a large part of Russian history, the central government is invariably the most powerful political player in our country. But sometimes this dominant political player encounters a deadly rival in the form of ... itself. Sometimes the processes of internal rotting, internal degradation and internal decay are set in motion in the structures of Russian central government. And if these processes go far enough, the central government suddenly collapses like a house of cards – and the supporting framework of our statehood collapses with it”10.

T. Voevodina: “The USSR collapsed virtually at the peak of its military and industrial might, or, rather, at it was sluggishly sliding down that peak. And the collapse was perceived by many citizens with delight and enthusiasm, it took place amidst stormy and prolonged applause. The overthrow of the sovok [a derogatory word for the Soviet Union or anything related to it. Translator’s note], judging by all these attitudes, was neither a conspiracy nor a coup, but a truly national affair. Although, of course, there was a conspiracy, and a coup, and betrayal, but nothing could have been accomplished without popular support, and not just support, but direct involvement”11.

monitoring research carried out by Minchenko Consulting Group. The authors of the regularly published reports about the political system write that in 2011–2012 “the elites were distributed between two poles, however unequal – Prime Minister Vladimir Putin and President Dmitry Medvedev”612, however, in the summer of 2012 the political system in Russia has taken a form in which Medvedev turned out to be “only one of several significant players, on par with the heads of the Rosneft and Rostec state corporations Igor Sechin and Sergey Chemezov, respectively, head of the Presidential Administration Sergey Ivanov and his first deputy Vyacheslav Volodin, Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobyanin, businessmen Gennady Timchenko and Yuriy Kovalchuk... At the level of individual ministries and government agencies, the participants of this narrow circle formed their own networks of friendly senior officials and their deputies, officials of key departments. The distribution of power between groups affected Russian regions as well – virtually every member of the Politburo 2.0 formed his own pool of governors”13. The functions of the formal head of government in this system were severely restricted and the President played the part of chief referee.

Thus, in the current Russian public administration system we see an increasing number of “equal players”, they form “friendly networks”, the competition between them is becoming more tough, and this competition takes place not only at the federal but also at the regional level (specific “ministries, institutions, departments”), and the goal of this struggle of “friendly clans” has nothing to do with promotion of national interests: the goal is to obtain power and economic resources of the

“Today, in addition to solving governance objectives as such, the ruling elite also attempts to secure its stability in the long term. To do so, it needs:

-

1. To convert power into property (through a new stage of privatization, use of budgetary resources and preferences by government agencies in order to develop profitable businesses, create new “rents”);

-

2. To make provisions for the transfer of property acquired in the 1990-2000s by inheritance;

-

3. To legitimize acquired property both in Russia and abroad.

Another objective of the ruling elite is to strengthen the coalition framework, eliminate unwanted members and attract a limited number of new ones.

Russia’s ruling elite can be described through the model of the Soviet collective power body – the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU CC). The process of ruling aims primarily to sustain the existing inter-clan balance... Russian power is a conglomerate of clans and groups that compete with one another over resources. Vladimir Putin’s role in this system remains unchanged – he is an arbiter and a moderator” 14.

country. In other words, we can talk not just about a confrontation of two political forces – the patriots and the liberals15, but about the emergence of several centers equivalent in their influence and engaged in a zero-sum game through the use of their competitive advantages. And the big question is: which of the two factors (lack of a single vector, deconsolidation of the ruling elite or Cold War 2.0 that is gaining momentum since Putin came to power and especially after his speech at the Munich Conference in 2007) is today a dominant threat to national security. Indeed, by and large, when talking about external threats, a phenomenon such as “probable adversary” is quite clear, and a talented strategist (the President is, no doubt, such a strategist) sees very clearly the steps that must be taken and that will find support among citizens.

Everything is much more complicated in the “internal war” that Vladimir Putin has to carry on so as not to allow a kind of “feudal” fragmentation inside the political system. But the consequences of this war can become no less fateful and tragic for Russia than external expansion.

In the previous issue’s editorial we cited some factual data and expert assessments showing that “over the past 25 years the “capitalism for the few” was firmly rooted in the ranks of the ruling elite. It became “the basis of the political and economic structure of the country” 16. The bulk of Russia’s production assets (82%) is privately owned. Eighteen percent of production assets is owned by the state, and for the period from 2000 to 2015, the value of this indicator decreased by 7 p.p. (from 25 to 18%; Table )817.

Another long-standing problem of Russian society is a high level of inequality, which, according to experts, twice exceeds the maximum permissible level. As a matter of

According to the Federal State Statistics Service, the ratio of the average income of the richest 10% to the poorest 10% (R/P 10%) in Russia is 16.

According to expert estimates, 8 is a critical threshold value of R/P 10%18, the achievement of which demonstrates “a high level of risks in the functioning of social relations, a threat of transition to high volatility, low predictability and, hence, the need for rapid intervention on the part of the authorities in order to reverse the dangerous trends”19.

According to the United Nations, R/P 10% should not exceed 8–10, “otherwise the situation in a democratic country is fraught with social cataclysms”20.

fact, the dynamics of inequality, as economist T. Piketty proved, for the last 110 years experienced typical global changes with the fall of inequality in the mid-twentieth century and its subsequent growth in the 1980s – 1990s. Russia is no exception here; however, the exception for Russia lies in the psychological factor – the behavior of the wealthiest population groups that accumulate their capital in tax havens and ignore the interests of national development. “If in a situation of high inequality the savings are not transformed into investments that create new jobs, then inequality puts on “black robes” and becomes a gravedigger of economic growth”21.

Fixed assets, broken down by forms of ownership (at the end of year; for the full book value)

|

Year |

Mln rub. (1990 – bln rub.) |

Percentage to the outcome |

||||

|

All fixed assets |

Including by forms of ownership |

All fixed assets |

Including by forms of ownership |

|||

|

State-owned |

Non-governmental |

State-owned |

Non-governmental |

|||

|

1990 |

1927 |

1754 |

173 |

100 |

91 |

9 |

|

2000 |

17464172 |

4366043 |

13098729 |

100 |

25 |

75 |

|

2010 |

93185612 |

17705266 |

75480346 |

100 |

19 |

81 |

|

2011 |

108001247 |

19440224 |

88561023 |

100 |

18 |

82 |

|

2012 |

121268908 |

21828403 |

99440505 |

100 |

18 |

82 |

|

2013 |

133521531 |

24033876 |

109487655 |

100 |

18 |

82 |

|

2014 |

147429656 |

26537338 |

120892318 |

100 |

18 |

82 |

|

2015 |

160725261 |

28930547 |

131794714 |

100 |

18 |

82 |

Sources: Gubanov S.S. Antinauchnyi mif (o 70% gossektora) i ego sotsial’nyi podtekst [Unscientific myth (about the 70% of the public sector) and its social implication]. Ekonomist [The Economist], 2017, no. 8, p. 6.; Rossiiskii statisticheskii ezhegodnik, 2016: stat. sb. [Russian statistics yearbook, 2016: statistics collection]. Moscow: Rosstat, 2016. P. 288.

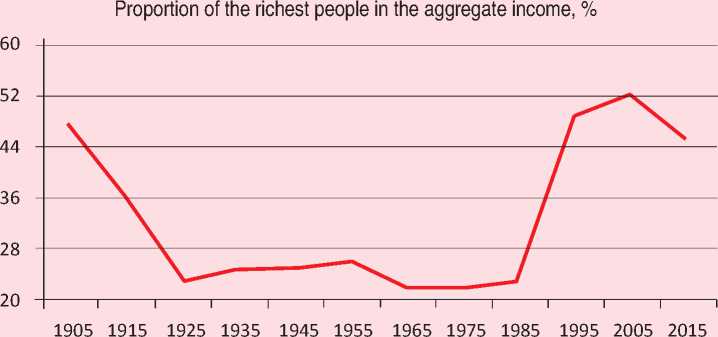

That is why by the 100th anniversary of the Revolution, the inequality in Russia has returned to the level of 1905 (Figure). The proportion of income of the richest 10% of Russians in the aggregate income for the period from 1905 to 2015 has remained virtually unchanged (approximately 46–48%) or, in other words, the earnings of 10% of Russians are equal to almost half of the incomes of the entire Russia’s population. The diagram is a most striking evidence of inefficiency of the public administration system over the past 30 years; besides, it proves that the President’s work to nationalize the ruling elites responsible for the dynamics and quality of life of Russians remains unfinished, as well as the work to ensure national security.

Source: Gaiva E., Gurova T., Obukhova E. Ne v otdel’no vzyatoi strane [Not in a particular country]. Ekspert [The Expert], 2017, no. 38, September 18–24.

can be an explanation for the fact that so far the assessments of performance of the authorities pay too little attention to people’s subjective estimates. The President has repeatedly stated that public opinion is the main criterion that defines government performance22 (and in this sense it is no coincidence that an indicator such as the rate of people’s satisfaction with the work of the governor was included in the list of criteria for evaluating the performance of governors23). However, even at present, experts say that this principle does not work, at least at the system level.

The vulnerability of the Russian economy and its adverse effects on the dynamics of people’s standard of living and quality of life24 are perhaps the main but not the only evidence of deconsolidation of political forces in the current Russian system of government. Numerous examples from everyday Russian reality prove it, as well: corruption of officials, the Government’s failure to implement the May decrees of the President, the Government’s ill-

M.K. Gorshkov: “In order to assess the performance of officials, it is necessary to use alongside the dry figures of objective indicators of economic development the indicators of subjective nature. How high is the degree of people’s satisfaction with different aspects of life: are you satisfied with the standard of living? With your salary? With the quality of healthcare? With education that your children obtain? With the quality of leisure?..

We have 15 such indicators. Does anyone take them into account? Is anyone interested in them? If these indicators were included in the body of state statistics, then, I am afraid, half of the officials would loose their jobs” 25.

considered solutions (monetization of benefits in 2004, introduction of the electronic toll collection system Platon in 2015, etc.

The latest such facts include the bankruptcy of the Russian air carrier VIM-Avia, which became another26 sign of a gradually emerging crisis in the civil aviation industry and, by and large, in the public administration system on the whole.

L.I. Kravchenko: The main problem of civil aviation is “a loss of state control over the industry because of a large-scale privatization, including the privatization of airports. As soon as private business entered the industry (especially it concerns the airports) it established market relations in it, replacing national security and public interest – rather vague notions in the eyes of businesspeople – with concrete market terms like profit and competition. High rates of aircraft servicing at airports – that is the prospect of business. What this approach leads to is clearly seen on the example of Domodedovo Airport, where business neglected proper security measures, which led to tragic consequences like the explosion on January 24, 2011, in which 37 people were killed and 170 wounded”27.

Experts point out: “The Government has delayed the solution to the problem, and it provoked an open crisis... The state of affairs in the aviation industry in Russia in general is in line with the state of affairs in the Russian economy: problems are ignored, decisions are made to extinguish the fire rather than prevent its breaking out, the industry lost its strategic importance for the state and shifted to the capitalist mode of functioning, when the category of “profit” determines the cost of routes, the level of security, the quality of service and so on” 28 .

Crisis symptoms are just as obvious in the Russian science, a “forge” of knowledge that is a major driver of national competitiveness in the world of high technology and scientific progress. “The conflict between the government that was making continuous efforts to reform the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Academy that was fighting for the remnants of financing and organization of the system of institutions dates back to the 1990s, when the funding of science collapsed”29. In 2013, a reform of RAS was carried out in the mode of “special operation or blitzkrieg”30; the reform launched the process of reorganization of the Academy. In March 2017, the Academy remained without its president because all the candidates refused to be nominated for the office. And it was only in September 2017 that the President endorsed a candidate elected by academicians and confirmed the appointment of A. Sergeev as RAS President. A. Sergeev is director of Nizhny Novgorod Institute of Applied Physics of the Russian Academy of Sciences, a person whom the government congratulates through “clenched teeth” since it “has desperately lobbied other candidates for the post”31.

A. Chuykov: “Sergeev is a very uncomfortable and, in the good sense of the word, uncompliant person for clueless government officials to deal with. He is a renowned scientist with a clear and independent program for taking the Academy of Sciences out of the crisis into which it was plunged by Fursenko, Kovalchuk, and others of that ilk”32.

Thus, the current situation marked by a lack of consolidation of political elites on the principles of national interests and national security, as well as the resulting negative processes in the economy, in the dynamics of the standard of living and quality of life not only justify the use of manual control mode to govern the country, but make it necessary. In fact, it is this very mode that supports people’s “last hope” in the action of the “chief arbiter” of the political system.

And then the reasonable question arises: what prevents the President from giving officials who failed to do their job a reprimand for incompetent performance or inform them about the loss of confidence timely and comprehensively, without allowing the obvious signs of crisis to reach their peak; what prevents him from bringing to justice for every such act not only the officials who are directly responsible for a certain sector, but also the representatives of the ruling elites who promote them through the ranks?

Answering this question we should note that in the course of his three presidential terms Vladimir Putin managed to create a system of government which, although being flawed, recognizes him as the main arbiter with extensive capabilities to transform this system.

In the last few years we see how the President is gradually implementing these capabilities. As his third term in office is coming to an end and Russia’s relations with the United States resume their natural (although tense) course, Vladimir Putin focuses more on internal politics, acting as a “regulator” in this sphere: he is implementing personnel changes among the governors; experts say to this: “It seems that Vladimir Putin has already launched a process of fundamental change in the composition of Russia’s administrative elite, which should help avoid an extremely conflict-ridden “Ukrainian” scenario in 2024. Perhaps this process has a short-term goal implying that a sufficiently broad transformation of the managerial elite will have a deterrent or even a sobering influence already in 2018 rather than in the distant 202433. Besides, experts note that “a powerful political potential that is not yet reflected in the four major Russian political parties, is accumulating in the State Duma, which under the leadership of speaker V. Volodin has undergone an “upgrade” from the point of view of elite and sector representation, received a severe disciplinary modernization, and enhanced the expert component of its work... It seems that after the presidential election, an attempt will be made to revive once again the political process in the country through rejuvenation and modernization of the parties and the Duma itself will gain weight and will play a more independent role in the decision-making system”34.

Thus, manual control mode is still on and, as the above facts prove, it is for a reason. Apparently, this mode will be necessary until the President fulfills his main goal, i.e. until he creates a check-and-balance system in which the power vertical at all levels of government is capable of self-restoring without losing its quality. The solution to this problem is of historical importance for Russia and, in fact, it is the foundation for Vladimir Putin’s successor. However, system-wide failures of public administration in the last 15 years show that, apparently, it is postponed for the period until 2024...

M. Rostovskii: “Today, everything still rests on the will of one individual. This situation needs to be changed. It must be changed, since as long as it does not change, the risk of the central government relapsing into internal degradation will hang over Russia like a sword of Damocles. But, unfortunately, such changes do not happen overnight. A minimum condition for them is a few decades of calm and stable development of the country. Unlike the U.S., it will take Russia quite a long time to get ready to “switch to autopilot” in its politics. In the foreseeable future, our country will be governed in “manual mode”. And this means that the political lessons of February 1917 will remain relevant for us for a very long time”35 .

The fourth presidential term will somehow have to mark the outcome of the President’s work on the implementation of the goals that he set out back in 199936. Moreover, during this period, the President will not only have to complete the creation of a political system capable of solving autonomously and efficiently people’s everyday problems, but also to ensure its viability, that is, to test it empirically by overcoming political or economic crises and adjusting it if necessary. It is an extremely difficult, but historically major task, and not much time is left to implement it.

The last (or, speaking more accurately, the final) six-year presidency of Vladimir Putin in the framework of the current legislation will need to complete the process of nationalization of the elites, which will make it possible to switch off manual control mode in many respects. Thus, this final term in office will ultimately provide an answer to the question whether the period of Putin’s presidency has been a period of lost opportunities or it was the reign of a talented leader who due to his personal qualities and with the help of manual control facilitated the country’s transition to a new stage of development since the collapse of the Soviet Union, through the painful and long adaptation of society to post-Soviet conditions, the transition to a state that is a center of the multipolar world and confirms this status not only in the international political arena, but also in the dynamics of the standard of living and quality of life of its people.

Список литературы The president's unfinished work. Public administration system is not ready to function without manual control

- Bol'shoe Pravitel'stvo Vladimira Putina i Politbyuro 2.0: doklad kommunikatsionnogo kholdinga "Minchenko konsalting" . 2012. 11 p..

- Glaz'ev S.Yu., Lokosov V.V. Otsenka predel'no kriticheskikh znachenii pokazatelei sostoyaniya rossiiskogo obshchestva i ikh ispol'zovanie v upravlenii sotsial'no-ekonomicheskim razvitiem . Vestnik RAN , 2012, vol. 82, no. 7, pp. 587-614..

- Gubanov S.S. Antinauchnyi mif (o 70% gossektora) i ego sotsial'nyi podtekst . Ekonomist , 2017, no. 8, pp. 3-27..

- Ilyin V.A. Razvitie grazhdanskogo obshchestva v Rossii v usloviyakh "kapitalizma dlya izbrannykh" . Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz , 2017, no. 4, pp. 9-40..

- Lokosov V.V. Metod predel'no kriticheskikh pokazatelei i otsenka chelovecheskogo potentsiala . Ekonomika. Nalogi. Pravo , 2012, no. 5, pp. 71-75..

- Politbyuro 2.0: renovatsiya vmesto demontazha: doklad kommunikatsionnogo kholdinga "Minchenko konsalting" ot 23.08.2017 . 21 p..

- Polterovich V.M. Reforma RAN: ekspertnyi analiz . Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost' , 2014, no. 1, pp. 5-28..

- Toshchenko Zh.T. Fantomy rossiiskogo obshchestva . Moscow: Tsentr sotsial'nogo prognozirovaniya i marketinga, 2015. 668 p..