The Relationship between Slack Resources and Performance: An Empirical Study from China

Автор: Heping Zhong

Журнал: International Journal of Modern Education and Computer Science (IJMECS) @ijmecs

Статья в выпуске: 1 vol.3, 2011 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Although organizational research posits various relationships between a firm’s slack resources and performance, findings to date have been ambiguous. The purpose of this study is to attempt to reconcile previous views of the relationship between slack resources and performance through employing empirical analysis based on survey data from 47 pharmaceutical and chemical firms in Henan Province of China. The results indicate that the relationship between slack resources and the performance is inverse N-shaped. Results provide evidence of a curvilinear relationship between slack resources and performance and broadly demonstrate that relationships differ based on industry circumstances and slack resources. Additionally, this study is the first to empirically identify an inverse N-shaped relationship between slack resources and performance, indicating that, in certain industry circumstances, little and much slack resources are bad for performance. Overall, results highlight the importance of additional research into intervening factors impacting the slack–performance relationship.

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/15010041

IDR: 15010041

Текст научной статьи The Relationship between Slack Resources and Performance: An Empirical Study from China

Published Online February 2011 in MECS

Keeping sustainable development is always an ultimate aim for managers in firms. From the viewpoint of the resource-based theory, a firm’s unique portfolio of tangible and intangible resources influences the extent and direction of a firm’s expansion. In this regard, numerous studies have proposed that resources enable firms to create static and dynamic synergies by applying resources required for sustainable development [1]. Thus, a firm’s performance and development is influenced by how the management team conceptualizes and uses a firm’s resources. Some scholars explore the relationship of resources, performance and growth from the perspective of total resources [2]; but classic views of resource-based argued the importance of resource slack as a driver of growth rather than the total quantity of resources possessed by a firm [3]. Slack is a dynamic quantity that represents the difference between the resources currently possessed by a firm and the resource demands of the current business. The slack of resources is important because two firms may possess the same level of resources but differ in the resource exploiting of their current business. Hence, the two firms would have different levels of slack and thus also differ in their growth potential [2] . Consequently, how to optimize firm slack resource allocation and its impact on performance has substantive theoretical and practical implications.

However, despite the importance of firm slack resource allocation, the existing literature provides no compelling answers regarding whether slack resources facilitates or inhibits performance [4-7]. How does slack resources affect firm performance? Organization theorists typically argue that, despite its costs, slack resources buffers a firm’s technical core from environmental turbulence, and thus enhances its performance [3,6,8,9]. In contrast, agency theorists often suggest that slack resources is a source of agency problems, which breeds inefficiency, inhibits risk-taking, and hurts performance [6,10,11]. Rather than weigh in on one side of the debate for or against the performance-enhancing benefits of slack resources, some scholars have attempted to reconcile these perspectives and proposed an inverted U-shaped relationship between slack resoureces and performance [6,12,13]. The current literature has not reconciled these perspectives, and the issue regarding the influence of slack resources on performance remains an interesting but not fully explored issue [6,14].

Several studies have attempted to build on previous findings and refine the relationship between slack resources and performance under different research settings, such as environmental contexts [6,15], industry contexts [3,7], and organizational characteristics [4,16,17]. Although these studies provide numerous useful insights, they leave room for further theorizing and empirical study [14]. First, previous empirical and theoretical investigations have tended to neglect competition condition in a industry. Firms in different competition condition require different amounts of slack resources to maintain their competitiveness. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the influences of different competition condition to avoid inconsistent results. Second, there are rare slack-performance studies on Chinese firms in current literatures, making it necessary to further study the relationship between slack resources and performance for Chinese firms because Chinese economy has been paid more and more attention all over the world.

This study addresses the gaps in the literature by revisiting the relationship between slack resources and performance. To fill this void, this study employed a empirical analysis based on the sample from 47

pharmaceutical and chemical firms in Henan Province to examine extant research results. Specifically, I focus on firms of a industry in China, based on survey data, to investigate whether slack resources contributes toward or inhibits firm performance.

-

II. Theoretical Background And Hypothesis

Although Barnard (1938) had discussed the role of slack in his early work, the specific label of ‘slack’ had not been coined until March and Simon published their seminal book in 1958 [6,18,19]. Cyert and March (1963) defined slack as ‘‘the difference between total resources and total necessary payments’’. This definition was followed by Bourgeois (1981) who added that ‘‘slack is that cushion of actual or potential resources which allows an organization to adapt successfully to internal pressures for adjustment or to external pressures for change in policy, as well as to initiate changes in strategy with respect to the external environment’’. Based on Bourgeois’ definition, Sharfman et al (1988) emphasized two characteristics of slack resources. One is that slack resources must be visible to the manager and employable in the future; the other characteristic is that different types of slack resources give managers dissimilar degrees of discretion in attempting to protect their firms from internal and external pressures. In addition, Nohria and Gulati (1996) defined slack resources as ‘‘the pool of resources in an organization that is in excess of the minimum necessary to produce a given level of organizational output’’ [20]. Moreover, they noted that these resources vary in type, including excess inputs (e.g., surplus employees, idle capacity, and capital expenditures) and overlooked or unexploited opportunities to increase outputs (e.g., margins and revenues to be gained from customer). Most recently, George (2005) defined slack as ‘‘potentially utilizable resources that can be diverted or redeployed for the achievement of organizational goals’’ [16].

In summary, the literature has defined three facets of slack resources. First, slack resources is conceptually defined as resources not being used to the fullest extent possible. Second, slack resource characteristics include location [4] and accessibility (e.g., immediately versus deferred; [7]). Third, the two central purposes of slack resources are to act as a buffering mechanism to counter threats and also as a facilitator to exploit opportunities [21]. Why does slack resources emerge? The notion of endogenous growth of Penrose (1959) conceives firms as organic entities that cultivate and accumulate resources. Consequently, utilizing and leveraging these excess resources to capture external opportunities via managerial capabilities can drive firm growth. Penrose also pointed out that the attainments of excess resources are: indivisibility of resources, reuse of resources under different circumstances, and continual establishment of new productive services [14]. Based on the analysis all above, For the purposes of this study, slack resources will be defined as the resources readily available to an organization that are in excess of the minimum necessary to produce a given level of organizational output as well as the resources that are recoverable from being embedded in the firm [22], which is potentially utilizable resources that can be diverted or redeployed for the achievement of organizational goals [16].

In theory, if a firm can identify and obtain resources for firm development from its interior or exterior timely and accurately, and maintain the sum of resources which meets the need of current business exactly, namely, the amount of slack resources is zero, the performance would reach the optimization, but it is impossible in practice. In order to respond to problems such as fluctuations in demand, a firm should have to keep some slack resources, which would lead to increasing cost. In order to fulfill the commitment to the staff, take on some social responsibilities and maintain harmony and stability of the organization, a firm should have to keep certain slack resources, this would also increase cost[23]. In pursuit of new goals and strategies, a firm should have to keep some slack resources[2], this would increase cost because the slack resources could not produce performance before new strategy is put in practice. So the conclusion is made that slack resources on the low side is negatively related to the performance of firms. Therefore, I suggest:

Hypothesis1. Slack resources on the low side is negatively related to firm performance.

When there is moderate slack resources, a firm has capability to explore and take advantage of opportunity provided by environment. The firms with slack resources have more strategic choices than those without slack resources [24,25], thereby they could choose strategic opportunities supported by slack resources available to enhance performance. Bromiely ( 1991 ) argued that slack resources related to competition provide strategic advantage for firms[24], as a result, there is a conclusion that to enhance slack resources related to competition will strengthen the firm’s competitive advantage and improve performance. In a word, moderate slack resources enables managers to pursue new targets and strategies actively, which may leads to improvement of firm performance. From the viewpoint of resource-based theory, the more slack resources a firm has, the more potential growth and better performance a firm has[2]. Accordingly, I could draw a conclusion that moderate slack resources will be positively related to the performance of firms. Therefore, I suggest the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis2. Moderate slack resources is positively related to firm performance.

On the other hand, slack resources is argued to be synonymous with waste, and a sign of managerial selfinterest, incompetence, and sloth. From an agency theory perspective, managers inherently have a set of goals, such as the pursuit of power, prestige, money, and job security, that are not always aligned with those of principals, managers may use slack resources to engage in excessive diversification, empire-building, and on-the-job shirking[6]. These ‘‘slack resources as inefficiency’’ perspective posits that slack resources can encourage satisficing, politics, or self-serving managerial behaviors that hurt performance. At the same time, too much slack resources would encourage a firm to choose some suboptimal projects [20]; and it would reduce firms’ performance. So, I can reach a conclusion that slack resources on the high side will be negatively related to the performance of firms. Therefore, I suggest the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis3. Slack resources on the high side is negatively related to firm performance.

There is little reason to believe that slack’s performance-enhancing effect—if any—is linear. In other words, there must be a limit beyond which further ‘hoarding’ of slack may backfire [6]. The relationship may well be an curvilinear. Some researchers have speculated that ‘there is an optimal level of slack resources for any given firm. If the firm exceeds that level, performance will go down [12,13], and an inverse U-shaped relationship between slack resources and performance is suggested [6]. Although Bromiley (1991) hypothesizes that the slack–performance relationship may be U-shaped—high and low slack resources is associated with better performance and moderate slack may lead to poorer performance—his results do not support this hypothesis and instead find a linear, positive relationship between slack resources and performance [6,24]. Behavioral arguments suggest that the impact slack resources on performance is decided by the relation between actual slack resources and target slack resources. Slack resources more or less than the target scope will urge a firm to take measures to improve performance. But the slack resources at the target scope will make a firm Satisfy present condition and don’t think enterprising, thus it reduce the firm’s performance [25]. In order for research on slack resources to advance, it is important to determine the optimum level of slack resources with better precision. Based on above discussion, I suggest hypothesis as following:

Hypothesis4. There is a nonlinear inverted N-shaped relationship between slack resources and firm performance. That is to say, when slack resources is on the low side, slack resources is negatively related to firm performance; when slack resources is moderate, slack resources is positively related to firm performance; when slack resources is on the high side, slack resources is negatively related to firm performance.

-

III. Methodology

-

A. Samples

A questionnaire survey research method was used to seek responses from some typical firms in Henan Province of China. According to a sample frame provided by the correlative province bureau, we randomly selected 60 pharmaceutical and chemical firms as our study firms. Then, interviewers telephoned potential respondents and solicited personal interviews, and 47 firms accepted our survey. Descriptors of the sample are summarized in Table 1 to Table 4.

Table 1 the distributing of respondents’ job

Respondent post Number Percentage (%)

|

Intermediate manager |

19 |

40.4 |

|

Senior manager |

15 |

31.9 |

|

General manager |

6 |

12.8 |

|

President |

1 |

2.1 |

|

Other |

6 |

12.7 |

Table 2 the distributing of respondents’ educational background

|

Education |

Number |

Percentage (%) |

|

Senior high school |

2 |

4.3 |

|

Junior college |

24 |

51.1 |

|

Undergraduate |

15 |

31.9 |

|

Postgraduate |

6 |

12.8 |

Table 3 the distributing of firm ownership of respondents

|

Firm ownership |

Number |

Percentage (%) |

|

State-owned firm |

10 |

21.3 |

Private-owned firm 26

55.3

Foreign capital-owned

Other firm

12.8

10.6

Table 4 the distributing of firm size of respondents

|

Firm size |

Number |

Percentage (%) |

|

Oversize firm |

1 |

2.1 |

|

Big firm |

12 |

25.5 |

|

Middle firm |

24 |

51.1 |

|

Small firm |

10 |

21.3 |

Data was collected through intensive, in-depth interviews and usually one-to-one. Every interview was about one hour to 90 minutes in duration. Our interviewers had face-to-face communication and explanation with the top managers and relevant department directors of the firms; so that the demand of fulfilling the questionnaire was understand by them. Our interviewees were top firm managers, so they had a comparatively deep understanding of the firm’s slack resources and management activity, and their responses to the questionnaire could actually demonstrate the firm’s condition.

A total of 60 pharmaceutical and chemical firms were surveyed, 50 pharmaceutical and chemical firms provided complete information. Unfortunately, three sample firms were ineligible because of company liquidation or inadequate completion of the survey questionnaire. That is, 47 pharmaceutical and chemical firms s had all the necessary data. The overall response rate for the survey was 83.3 percent (50 out of 60, and the effective rate was 78.3 percent (47/60). Moreover, to assess the nonresponse bias, this study compared the responding firms with the non-responding firms and found no significant differences in terms of firm size, age, employee numbers and assets. Therefore, the sample used by this research have better representative and can satisfy the research’s demand.

-

B. Variables measure

Firm performance

There are great numbers of measurements on firm performance in present literatures, such as financial performance, strategy performance and so on. Because the statistical data is distempered or not willing to publish in many firms, it is hard to measure in quantity. But in their practical activities, managers collect and hold some useful information about their opponents in their industry, so they are clear about the comparative level of performance of their firm. Thereby, I use for reference measure item of prior studies[23,25], use the method of perception to measure comparative level of firm performance compared with its main opponents. So this paper chooses four items to measure firm performance: (1) sales growth; (2) asset-profit ratio; (3) increase of market share; and (4) net profit. In the questionnaires the answers were measured on five-point Likert scale ranging from 1, strongly draggle, to 5, strongly keep ahead. The Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for this scale is 0.927.

Slack resources

The measure of slack resources borrow from the studies of Fang & Wang (2008)[26,27]. According to their definition and characteristics of the slack resources, this paper measure slack resources from the two aspects of the shared level of resources(reflecting the use range of resources as well as the conversion efficiency among differnet uses of the resources) and the multi-purpose in nature(reflecting the use range of resources), mainly choose three items to measure the level of slack resources: (1) The resource sharing level of various departments within the firm is very high; (2) New uses of existing resources in a firm are often found; (3) Some new resources or new mix of existing resources in a firm are often found. In the questionnaires the answers were measured on five-point Likert scale ranging from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. The Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for this scale is 0.840.

Control variable

Like prior studies, this study adopts total capital to measure the size of a firm, and take it as a control variable. The competition pressure that a firm faces is more big, the resources of the firm are more needed more effective exploitation. Since the competition condition among firms in different industry, this study also take the competition condition in a industry as a control variable, which is measured on 5-point Likert scale, using the scale from 1-5, which means respectively few competition, not severe competition, general, severe competition and very severe competition. Moreover, slack resources is also time-dependent in both its accumulation and its deployment [8,9,13]. Older firms are more likely to possess large amounts of slack than younger firms and to be aware of their resource demands, conditions that help the older firms generate and deploy slack effectively [16]. Accordingly, this study also take the age of a firm as a control variable.

-

C. Analyses and Results

I test my model with the statistical software SPSS 13.0 and use exploratory factor analysis to test every index. In order to test the hypothesis all above, the paper draws on methods from Nohria & Gulati (1996), Jiang & Zhao(2004), Zhong et al(2008), uses once, twice, thrice regression equation model including independent variable to process hypothesis testing. The regression equation model is as follow:

performance = в 0 + в 1 size + Aage + Acomp

+ Avar + e 5 var 2 + Avar 3 + e

I use the method of stepwise regression, and all variables are standardized before regresion analysis. If thrice regression equation model is better than model including once and twice regression equation, the N-shaped or inverted N-shaped relationship would be existed [16,23,25]. The result of hypothesis testing show as Table 5 to Table 7.

Table 5 Model factor loading of the elements and Cronbach’s α

|

Elements discribing indicators (N=47) |

Factor loading |

|

Firm performance ( Cronbach’s α = 0.927 ) |

|

|

V1 Sales growth |

0.926 |

|

V2 Asset profit ratio |

0.918 |

|

V3 Increase of market share |

0.881 |

|

V4 Net profit |

0.906 |

|

Slack resources ( Cronbach’s α = 0.840 ) |

|

|

V5 The resource sharing level of various departments |

0.802 |

|

within the firm is very high |

|

|

V6 New uses of existing resources in a firm are often |

0.917 |

|

found |

|

|

V7 Some new resources or new mix of existing |

0.889 |

|

resources in a firm are often found |

|

Table 6 |

Means, standard deviations and correlations |

|

variables |

mean s.d. 1 2 3 4 |

|

1 Firm size |

49138 120702 |

|

2 Firm age |

18.273 16.33567 0.87+ |

|

3 4.109 |

0.9939 |

0.094 |

0.264+ |

|

|

Competition |

||||

|

4 Slack 3.7408 |

1.16424 |

-0.094 |

0.105 |

0.020 |

|

resources |

||||

|

5 Firm 3.4330 |

0.80726 |

0.257+ |

0.192 |

0.012 0.372* |

|

performance |

||||

|

*** p <0.001 |

** p <0.01 * p <0.05 + p <0.10 |

|||

Table 7 Regression model of slack resources and firm performance

|

variables |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

|

Firm size |

0.233 |

0.307* |

0.269* |

0.321* |

|

Firm age |

0.231 |

0.158 |

0.130 |

0.101 |

|

Competition |

-0.370* |

-0.405** |

-0.347* |

-0.387** |

|

Slack |

0.476** |

0.430** |

0.934** |

|

|

resources |

||||

|

Slack |

-0.223 |

-0.306* |

||

|

resources 2 |

||||

|

Slack |

-0.581* |

|||

|

resources 3 |

||||

|

F |

3.211* |

6.558*** |

6.073*** |

6.426*** |

|

R2 |

0.211 |

0.428 |

0.472 |

0.539 |

|

Adjusted R2 |

0.145 |

0.363 |

0.394 |

0.455 |

0.60 was considered as the cut-off value [32]. As shown in Table 5, two Cronbach’s alpha values are more than 0.80. These results suggest that the theoretical constructs exhibit good psychometric properties.

Findings

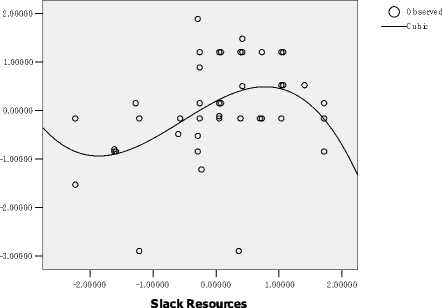

Descriptive statistics and regression results are shown in Table 5 to Table 7, respectively. The results of exploratory factor analysis from table 1 indicate that factor loading and Cronbach’s alpha are more than 0.70, every index is in accordance with requirement of hypothesis testing. Table7 presents results of the testing of the four hypotheses. Goodness-of-Fit test and significance test from Table 7 indicate that model 4 is better than model 2 and model 3. Model 4 contains every hypothesis, that is negative relationship when there are slack resources on the low side, positive relationship when there are moderate slack resources; negative relationship when there are slack resources on the high side ( в 4 = 0.934 , p = 0.001; в 5 =- 0.306 , p = 0.027; в 6 = - 0.581 , p =0.036). Meanwhile, collinearity and heteroscedasticity test indicate that there is no multicollinearity problems and heteroscedasticity issues (relevant test data are ignored). Therefore, all hypotheses from hypothesis 1 to hypothesis 4 are supported by these testing. Regression curve as Fig. 1 (control variable is ignored).

Firm Performance

Figure 1 Regression curve

-

IV. Discussion And Conclusion

Contributions

In this study, my contributions focus on the building of an inverted N-shaped model that clarify the relationship between slack resources and firm performance. Moving beyond Bromiley (1991), Tan and Peng(2003), Jiang and Zhao(2004), my work, to the best of my knowledge, presents the first set of evidence on such a relationship between slack resources and firm performance. I have advocated and documented a middle ground out of the intractable debate on the role of slack between organization and agency theories. Thus, the right question to ask is not whether slack is uniformly good or bad for performance, but rather, what range of slack is optimal for performance.

Although this study’s findings provide support for the general proposition that there is a curvilinear relationship between slack resources and performance in at least one industry, my findings differ from former researches because I suggest an inverted N-shaped model between slack resources and firm performance. As such, it represents another demonstration that the seemingly contradictory attributions made to slack resources can be reconciled when explaining the impact of slack on performance. That is to say, my findings help reconcile the debate not by finding that one theory is more superior than the other, but by specifying the circumstances under which each is likely to be supported. The findings suggest (1) that organization theory is more insightful when a firm has moderate slack resources, and (2) that agency theory is more significantly supported when a firm has much or little slack resources. Therefore, theoretically, this paper calls for better specification on the nature of slack when advancing theory—in both developed and emerging economies—as opposed to simplified, onesided arguments such as ‘slack is good or bad’ typically found in the literature. Furthermore, this study uses different methods to measure slack resources, which is not only measure the slack of the amount of resources but also measure the slack of the value of resources. Therefore, this study’s finding is an important extension of the Tan and Peng (2003) findings in that it was based on using financial measures of slack.

This study follows up on the suggestions of Tan and Peng(2003), Jiang and Zhao(2004) regarding further slack research. Specifically, this work answers the following question: how much slack enhance performance under a specific industry competition condition? The results of this empirical study elucidate the relationships between slack resources and performance, and thus go beyond the simple theoretical question of whether slack resources enhance performance.

In summary, this paper contributes to the literature by theoretically arguing for a better specification of the nature of slack when engaging in the debate on the role of slack, empirically addressing this issue within the context of economic transitions such as China, and methodologically employing survey methods to obtain convergent results.

Limitations and future research directions

Despite some contributions to the literature and certain practical applications, this study has limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, the crosssectional data used in the study do not allow for causal interpretation among the factors, although we requested that the sample firms supply data for the most recent three-year period. Ideally, this study would have benefited from a time lag between the measurement of the independent and dependent variables in order for a causal relationship to be determined. I hope that this study will serve as a foundation for new studies in the future. A second limitation is that this study does not consider the different influences of different type slack resources such as available slack, recoverable slack on firm performance. Because different type slack resources have different character and value, the exploitation of different slack resources will produce different results. This should be a future research topic. Additionally, my findings and results are unique to the Chinese. Although, as the largest emerging economy, China has attracted significant research attention recently [33], future researchers need to explore the generalizability of my findings by conducting studies in different institutional environments (e.g., Chile, Hungary, India). Even within China, I need to caution that my findings probably only captured one snapshot during the evolution of China’s firm management reforms. While some issues confronting Chinese state-owned firms may be unique (e.g., managerial incentive to hoard slack), others may be relevant for non- state-owned firms as well (e.g., social networks and diffusion of the slack-hoarding behavior) [6,34]. Therefore, careful studies comparing and contrasting how slack affects strategy and performance among collective-, private-, and foreign-owned firms will be necessary [6,35,36,37].

Conclusion

Slack resources and performance exhibit complex curvilinear relationships in addition to simple nonlinear relationships. Balancing and optimizing slack is therefore a prerequisite for performance enhancing. Notably, different levels of slack resources have distinct impact on performance. Slack resources exhibit an inverse N-shaped relationship with performance. The results indicate that keeping moderate slack resources is propitious to firm development, but little and much slack resources may reduce firm performance. Therefore, it provides a firm a theoretical basis for a firm to cut slack resources. Restated, too much and too little slack resources can inhibit performance. Both slack resources should be optimized to maximize performance. Overall, I suggest that although both organization and agency theories are insightful to help us probe into the relationship between slack resources and firm performance during economic transitions, neither of them offers a complete picture. As a result, my findings call for a contingency perspective to specify the nature of slack when discussing its impact on firm performance.

Acknowledgment

This paper is supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (70671111), the Soft Science Research Project of Henan Province (092400440088), the Natural Science Research Program of Henan Education department (2008A630041) and the Major Special Project of Xuchang University (2010ZD007).

Список литературы The Relationship between Slack Resources and Performance: An Empirical Study from China

- Foss, N.J. and Christensen, J.F., “A market-process approach to corporate coherence”, Managerial and Decision Economics, 2001, Vol. 22 Nos 4/5, pp. 213-26.

- Mishina, Y., Pollock, T.G. and Porac, J.F., “Are more resources always better for growth? Resource stickiness in market and product expansion”, Strategic Management Journal, 2004, Vol. 25, pp. 1179-97.

- Penrose, E.T., “The Theory of the Growth of the Firm”, Wiley, New York, NY, 1959.

- Singh J., “Performance slack and risk taking in organizational decision making”, Academy of Management Journal, 1986, Vol.29, pp. 562–585.

- Cheng J, Kesner I., “Organizational slack and response to environmental shifts: the impact of resource allocation patterns”, Journal of Management, 1997, Vol.23, pp. 1–18.

- Tan, J. and Peng, M.W., “Organizational slack and firm performance during economic transitions: two studies from an emerging economy”, Strategic Management Journal, 2003, Vol. 24 No. 13, pp. 1249-63.

- Daniel, F., Lohrke, F.T., Fornaciari, C.J. and Turner, R.A., “Slack resource and firm performance: a meta-analysis”, Journal of Business Research, 2004, Vol. 57 No. 6, pp. 565-74.

- Cyert, R.M. and March, J.G., “A Behavioral Theory of the Firm”, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1963.

- Thompson, J.D., “Organization in Action”, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY, 1967.

- Fama E., “Agency problem and the theory of the firm”, Journal of Political Economy, 1980, Vol. 88, pp. 288–298.

- Jensen M, Meckling W., “Theory of the firm: managerial behavior agency cost and ownership structure”, Journal of Financial Economics, 1976, Vol. 3, pp. 305–360.

- Bourgeois, L.J., “On the measurement of organizational slack”, Academy of Management Review, 1981, Vol. 6 No. 1, pp. 29-39.

- Sharfman, M.P., Wolf, G., Chase, R.B. and Tansik, D.A., “Antecedents of organizational slack”, Academy of Management Review, 1988, Vol. 13 No. 4, pp. 601-14.

- Yi-Chia Chiu, Yi-Ching Liaw, “Organizational slack: is more or less better?”, Journal of Organizational Change Management, 2009, Vol. 22 No. 3, pp.321–342.

- Latham, S.F. and Braun, M.R., “The performance implications of financial slack during economic recession and recovery: observations from the software industry (2001-2003)”, Journal of Managerial Issues, 2008, Vol. 20 No. 1, pp. 30-50.

- George, G., “Slack resources and the performance of privately held firms”, Academy of Management Journal, 2005, Vol. 48 No. 4, pp. 661-76.

- Love, E.G. and Nohria, N., “Reducing slack: the performance consequences of downsizing by large industrial firms, 1977-93”, Strategic Management Journal, 2005, Vol. 26 No. 12, pp. 1087-108.

- Barnard C. “The Functions of the Executive”. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 1938.

- March J, Simon H. “Organizations”. Wiley: New York, 1958.

- Nohria, N., & Gulati, R., “Is slack good or bad for innovation?” Academy of Management Journal, 1996, Vol. 39, pp. 1245–1264.

- Wen-Ting Lin, Kuei-Yang Cheng , Yunshi Liu, “Organizational slack and firm’s internationalization: A longitudinal study of high-technology firms”, Journal of World Business,2009, Vol. 44, pp. 397-406.

- Geiger,S.W., Makri,M., “Exploration and exploitation innovation process: The role of organizational slack in R & D intensive firms”, Journal of High Technology Management Research, 2006, Vol. 17No. 1, pp. 97-108.

- Zhong Heping,Fang Runsheng,Sun Lianjian,Sun Xinqing, “Human Resource Slack and Performance: Evidence from Henan Province in China”, Proceedings of The Second International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management. England:World Academic Union,2008, pp. 513-519.

- Bromiley, P. “Testing a causal model of corporate risk taking and performance”, Academy of Management Journal, 1991, Vol.34No. 1, pp. 37-59.

- Jiang, C.Y&Zhao, S.M., “The relationship between organizational slack and performance: an empirical study”, Journal of management world, 2004, No. 5, pp. 108-115. (In Chinese).

- Fang, R.S&Wang, C.L. “On the Relationship Between Types of Decision-making and Organizational Slack”, R&DMANAGEMEN, 2008, Vol. 20No .5, pp. 47-51. (In Chinese)

- Zhong Heping. “The Impact of Organizational Slack on Technological Innovation: Evidence from Henan Province in China”, The 4th International Conference on Management and Service Science, 2010.

- Boyd B, Dess G, Rasheed A. “Divergence between archival and perceptual measures of the environment: causes and consequences”, Academy of Management Review, 1993, Vol. 18, pp. 204–226.

- Dess G, Robinson R. “Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures”, Strategic Management Journal, 1984, Vol. 5No.3, pp. 265–273.

- Cronbach, L.J., “Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests”, Psychometrika, 1951, Vol. 16, pp. 297-334.

- Nunnally, J.C., “Psychometric Theory”, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY, 1978.

- Yuan Li, Yongbin Zhao, Yi Liu, “The relationship between HRM, technology innovation and performance in China”, International Journal of Manpower, 2006, Vol. 27No. 7, pp. 679-697.

- Hoskisson R, Eden L, Lau C, Wright M., “Strategy in emerging economies”, Academy of Management Journal, 2000, Vol. 43, pp. 249–267.

- Peng MW, Luo Y., “Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: the nature of a micro-macro link”, Academy of Management Journal, 2000, Vol. 43No. 3, pp. 486–501.

- Peng MW., “Institutional transitions and strategic choices”, Academy of Management Review, 2003, Vol. 28No. 2, pp. 275–296.

- Tan J. “Innovation and risk-taking in a transitional economy: a comparative study of Chinese managers and entrepreneurs”, Journal of Business Venturing, 2001, Vol. 16No. 4, pp. 359–376.

- Tan J. “Impact of ownership type on environment, strategy, and performance: evidence from China”, Journal of Management Studies, 2002, Vol. 39No. 3, pp. 333–354.