The ruling elites: a problem for Russia's national security

Автор: Ilyin Vladimir Aleksandrovich

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: From the chief editor

Статья в выпуске: 4 (46) т.9, 2016 года.

Бесплатный доступ

ID: 147223865 Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223865

Текст ред. заметки The ruling elites: a problem for Russia's national security

of adequate response from the ruling elite to a long and growing discontent of the population concerning the dynamics of the standard of living and issues of social justice in society; this sooner or later leads to social explosion. Whether this social unrest is “fuelled” by geopolitical rivals, to what extent international political situation interferes with the internal policy of the state, etc. – all these issues are extremely important, but secondary. And in this sense, the main role in ensuring national security belongs to the effectiveness of public administration regarding the internal situation in the country; to put it more precisely – the effectiveness of the ruling elite in satisfying the critical needs of the population in improving the quality of life and social justice.

(Source: Ilyin V.A. Effektivnost’ gosudarstvennogo upravleniya i nakaplivayushchiesya problemy sotsial’nogo zdorov’ya [Public administration efficiency and the aggravation of public health issues]. Ekonomicheskie i sotsial’nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz [Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast], 2015, no. 6 (42), p. 26)

When describing the contemporary ruling elite in Russia, many experts do not mince their words; this fact in itself proves the existence of a protracted crisis in public administration2. The head of state has repeatedly drawn attention to the lack of efficiency in the work of Russian officials, their inaction against the background of aggravating social issues.

The relevance of the task to increase public administration efficiency in dealing with domestic issues is complicated by the randomness of global processes and the increasing pace of global competition.

Having established itself as a key player in the international political arena and confirming this status by subsequent actions3, Russia has taken upon itself the historical responsibility for making an adequate response to emerging global challenges; it has also taken up a role of full-fledged participant in geopolitical competition with leading world powers. After the collapse of the USSR, Russia’s geopolitical opponents could not but meet with hostility the emergence of another competitor. A hybrid warfare launched in these circumstances, on the one hand, showed that they are really afraid of Russia’s revival from obscurity of the 1990s; on the other hand, it increased dramatically the relevance of public administration efficiency issues in Russian domestic life, making them the most important weapon in global competition.

G. Hegel, the classic of the German philosophical thought, pointed out that history repeats itself, and it does it until people have learned the lessons they should learn from history.

A century ago, irreconcilable differences and geopolitical ambitions of leading world powers led to the outbreak of the First World War, in which 34 out of 56 sovereign states participated4.

For the past 100 years, the world civilization has reached a qualitatively new level of development. Technological progress has changed the social and demographic structure of society, brought the quality of life to a new level, led to the aggravation of new global threats (such as new diseases, concerning, first of all, mental health; the threat of nuclear war, depletion of natural resources, etc.).

However, although the entire global civilization and each individual state are fundamentally different from their counterparts of 100 years ago, they have a lot of similarities that help make historical parallels and learn from the past.

The present-day world is also plagued by contradictions: Russia is searching for ways to reduce international confrontation by establishing uniform rules of conducting foreign policy, but it is opposed by the growing geopolitical “appetite” of the U.S. in the Middle East and in Europe, due to which the problem of international terrorism and the uncontrolled influx of refugees in the countries of the Old World has come to the fore, resulting in not only social but also cultural and political crises. All this is accompanied by more complex threats associated with the unpredictability and randomness of world events that set increasingly complex issues before the capitalist system dominant in developed countries.

After the “successful” implementation of the strategic plan for the collapse of the Soviet Union5, the country that used to be one of the two most powerful nations of the world in the second half of the 20th century, the U.S. actually became a monopolist and dictated its political, economic and ideological will6. U.S. policy of double standards and its military intervention in the internal affairs of sovereign states have become a regular phenomenon. “The neoconservatives who after September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks got their hands on all the levers of Washington’s foreign policy proceeded from the fact that in a relatively short historical period (ten years), they would be able to suppress all their major competitors on the planet by economic, financial, and in some places – military means. After this the United States can preserve its “dollar empire”, continuing to rob the rest of the world”7.

However, along with the neoliberal model of capitalism spreading around the world, “its own contradictions and imbalances were accumulating and becoming more and more pronounced – first of all, the growth of income inequality that caused gradual reduction in demand for manufactured goods”8. After a few years of American hegemony, there appeared several signs suggesting that the dominant power with its economic, managerial, spiritual and value system was failing in its role as the sole leader: “The United States overstrained itself because of the need to carry on several wars at the same time”9.

In 2007, Russia again spoke about the dangers of a unipolar world and once again asserted itself as an equal international partner10. In 2008, the dependence of the world economy on the U.S. economy led to the fact that the mortgage and banking crisis in the United States (which began back in 2007) escalated into a global financial crisis that showed that “the ability of the liberal elites to control the situation are limited, and their resources are being exhausted”11.

Today leading foreign and domestic scientists predict difficult times for capitalism, which may bring it to a global crisis. They focus on the following theses:

-

1. “The world is accumulating the sources of a crisis that will be structural, i.e. no possible solution to this crisis can be found within the standard political and investment decisions of today... Capitalism cannot flourish, if institutions are not reformed, employment restored, and environmental, health and other issues somehow solved...”12

-

2. “Before the Global Financial Crisis ideas like the Efficient Markets Hypothesis and the Great Moderation were very much alive. Their advocates dominated mainstream economics… The result was a global economy in which both households and nations lived far beyond their means. It is clear that there is something badly wrong with the state of economics. A massive financial crisis developed under the eyes of the economics profession, and yet most failed to see anything wrong… The ideas that caused the crisis and were, at least briefly, laid to rest by it are already reviving and clawing their way through up the soft earth. If we do not kill these zombie ideas once and for all, they will do even more damage next time”13.

-

3. “In the second decade of the 21st century not only in Russia but in many countries around the world there emerged a need for a humanistic turn of the sciences of man and society, the turn that expresses a need for the humanistic evolution of society itself”14.

4. “Suddenly we find that socialism in the two leading countries in the capitalist world-system has not only been revived, but has exposed itself as a powerful political alternative to the dominant liberal mainstream... The liberal “end of history” ended too quickly. And if this wave has not reached us, it is only because both our liberalism and our capitalism are very specific, and our political process is far from the game played by the rules of the Western world. But it is impossible to shut out a revolution with the help of an idea, and there is no doubt that soon we will hear the steps of a new socialism in Russia as well”15.

The clash of capitalist and socialist development paradigms is expressed in the exacerbation of geopolitical competition and is accompanied by tensions in the international political situation, intermittent and protracted short-term local armed conflicts and revolutions breaking out in different countries. The existence of the nuclear weapon, which makes a world war meaningless since “there can be no winner in a global conflict”164 is, perhaps, the main barrier preventing the outbreak of a third world war, this time, a nuclear war.

However, the fact that a nuclear war is futile does not imply the absence of hostilities; it only “dictates” the way in which they are carried out. Today, the

leading world powers engage in hybrid warfare through information resources that deal with public consciousness. Thus, global competition between countries is unfolding against the background of the problems similar to those that led to the First World War 100 years ago. The only difference is that at the beginning of the 21st century, geopolitical rivalry is developing at a qualitatively new level – technological, economic, political, etc.

So today the task of finding historical parallels that are necessary for an effective learning of the lessons of history is especially relevant for all countries in the world and primarily for the key players (such as the U.S., China, EU countries, Russia, India) whose role is crucial for the further development of events in the international political arena.

Some causes of the Russian revolution 1905–1917

The First World War went down in history as one of the most cruel and slaughterous wars17. Participating in the war became for many countries “the last drop that spilled the cup” of internal contradictions that had accumulated and affected mostly general population. In the post-war years, many countries of Europe

-

17 According to expert estimates, Russian military losses during the First World War exceeded those of all other world powers. Irretrievable losses (killed in action, died of wounds, missing in action, died in captivity and did not return from captivity) amounted to: 3.3 million for Russia, 2 million for Germany, 1.5 million for Austria-Hungary, 1.4 million for France, 0.7 million for the British Empire, 0.5 million for Italy, 0.08 million for the U.S. (source: Stepanov A. Poteri naseleniya Rossii v Pervoi mirovoi voine [Loss of the population of Russia in the First World War]. Zhurnal “Demoskop Weekly” [Journal “Demoscope Weekly”], 2014, no. 623–624. December 15–31, p. 7).

and the world experienced a wave of revolutionary movements that ushered in a new era, called contemporary history. So did Russia, which, according to some experts, had lost more than any country in that war18.

“Not only did the Russian revolution change Russia, it also radically changed the whole world. And the present-day world would be unthinkable without it, just like the world of the 19th century – without the French revolution”19 .

The Russian revolution that started in 1905 in Saint Petersburg when Imperial troops opened fire on a crowd of workers during a peaceful march led by priest Georgy Gapon stemmed from Russia’s international situation and contradictions accumulated within Russian society itself. In the late 19th – early 20th century, the Russian Empire, despite the growth of the total industrial production, lagged significantly behind leading countries of the West by this indicator (Tab. 1).

Russia’s major problem consisted in its lagging considerably behind the Western countries in the stan dard of living and quality of life. By the end of the 19th century, the rural class comprised about 77% of the population (Tab. 2) . It should be mentioned that there was not much in common between the Russian peasant and the European hereditary landholder. Residents of a European village felt they were owners of the land to a much greater extent, than that they were its subjects. And such a village was moving toward a more profound change in the whole society, toward its transformation into an urban, market society... Even after the abolition of serfdom, on the threshold of the 20th century, the idea of hereditary land

Table 1. Shares in global industrial production

|

Country |

1881–1885 |

1896–1900 |

1913 |

|||

|

In % |

In % of the leader’s (U.S.) contribution to global industrial production |

In % |

In % of the leader’s (U.S.) contribution to global industrial production |

In % |

In % of the leader’s (U.S.) contribution to global industrial production |

|

|

Russia |

3.4 |

11.9 |

5 |

16.6 |

5.3 |

14.8 |

|

USA |

28.6 |

100.0 |

30.1 |

100.0 |

35.8 |

100.0 |

|

Great Britain |

26.6 |

93.0 |

19.5 |

64.8 |

14 |

39.1 |

|

Germany |

13.9 |

48.6 |

16.6 |

55.1 |

15.7 |

43.6 |

|

France |

8.6 |

30.1 |

7.1 |

23.6 |

6.4 |

17.9 |

Source: Petrov Yu. Rossiya v 1913 godu: ekonomicheskii rost [Russia in 1913: economic growth]. Nauka i zhizn’ [Science and life], 2014, no. 7, p. 6.

Table 2. Distribution of population of the Russian Empire by estates in 1897

|

Estate |

Men |

Women |

Both sexes * |

|||

|

persons |

% |

persons |

% |

persons |

% |

|

|

Noblemen by birth and their families |

583824 |

0,9 |

636345 |

1,0 |

1220169 |

1,0 |

|

Personal noblemen, officials and their families that did not belong to nobility |

303653 |

0,5 |

326466 |

0,5 |

630119 |

0,5 |

|

Clergymen of all Christian denominations and their families |

275813 |

0,4 |

313134 |

0,5 |

588947 |

0,5 |

|

Hereditary and personal citizens of honor and their families |

175689 |

0,3 |

167238 |

0,3 |

342927 |

0,3 |

|

Merchants and their families |

137522 |

0,2 |

143657 |

0,2 |

281179 |

0,2 |

|

Townsmen |

6534117 |

10,5 |

6852275 |

10,8 |

13386392 |

10,7 |

|

Peasants |

47969068 |

76,8 |

48927580 |

77,5 |

96896648 |

77,1 |

|

Military cossacks |

1448382 |

2,3 |

1480460 |

2,3 |

2928842 |

2,3 |

|

Non-Russians |

4423808 |

7,1 |

3874157 |

6,1 |

8297965 |

6,6 |

|

Finland natives without class distinction |

16811 |

0,0 |

18774 |

0,0 |

35585 |

0,0 |

|

Persons not belonging to these estates |

210801 |

0,3 |

143112 |

0,2 |

353913 |

0,3 |

|

Persons who did not refer themselves to any estate |

36410 |

0,1 |

35425 |

0,1 |

71835 |

0,1 |

|

TOTAL Russian subjects |

62115898 |

99,4 |

62918623 |

99,6 |

125034521 |

99,5 |

|

Foreign subjects |

361450 |

0,6 |

244050 |

0,4 |

605500 |

0,5 |

|

TOTAL Russian and foreign subjects |

62477348 |

100,0 |

63162673 |

100,0 |

125640021 |

100,0 |

* Calculations: Demoscope Weekly. Available at:

Source: Pervaya Vseobshchaya perepis’ naseleniya Rossiiskoi Imperii 1897 g. [The first General census of the Russian Empire, 1897]. Ed. by N.A.Troinitskii. Volume 1. Obshchii svod po Imperii rezul’tatov razrabotki dannykh Pervoi Vseobshchei perepisi nasele-niya, proizvedennoi 28 yanvarya 1897 goda [General national corpus of the data on the results of the First General Population Census made on January 28, 1897]. Saint Peterburg, 1905. Table 8. Distribution of population by estates and conditions.

tenure and, moreover, private ownership of land, did not ripen in the Russian society and seemed to be something foreign in the Russian village...”20

At the same time, despite Russia’s lagging behind the West in terms of socioeconomic structure and quality of life, Russian society in the 19th century already developed a feature that N. Berdyaev called “the instinct of state might”21. After the fall of Constantinople in the 15th century, Russia – “the only free Orthodox state after the fall of Byzantium”22 – has become a new geopolitical pole in Eastern Europe. The status of the “Third Rome” made it necessary for Russia to participate in European, if not global, affairs and, moreover, to participate as a principal actor, which required strong economic, political, military and cultural interaction with neighbors, primarily with the West... By the beginning of the 20th century, Russia felt like a powerful nation, accustomed to win, to push the boundaries and dictate its own will to the neighboring states”23.

However, “to feel like a powerful state” is not the same thing as to be one. Russia’s objective necessity to compete with the leading countries of the West was combined with its elementary lagging behind them in terms of political, economic, and social development. The level of productive forces in the country did not meet the requirements of that time. The tsarist regime was not able to find a way out of this contradiction; this fact led to the revolutionary events of 1905 and 1917 and the change of the regime, and predetermined the further development of Russia and the world in the middle of the 20th century.

Russia in the 20th and 21st centuries: history repeats itself

The pre-revolutionary Russian Empire, the Soviet Union in the period of its “decline” and today’s Russia are divided by significant historical time periods. For the past 100 years the Russian society and state, like the whole world, has changed qualitatively. It is sufficient to mention the revolutionary events of 1905–1917, the victory in the Great Patriotic War, the exploration of space and the invention of nuclear weapons and we will understand how different the eras of the early 20th and 21st centuries were. The 70-year period of the Soviet regime made the Soviet Union one of the main powers in the world, and today we can only guess what the possible level of economic development and political authority of Russia would have been, if the government had not made mistakes and had not failed to “feel” the changing needs of the population, and if it had not been for the betrayal of national political elites in the late 1980s that led to the “parade of sovereignties” and the subsequent collapse in all the spheres of life in the era of the “turbulent 1990s”.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the ruling elite of the Russian Empire failed to meet the growing needs of the wide layers of the population; the situation was similar in the late 1980s, when the ruling elite of the Soviet Union failed to create the conditions to meet the needs of Russians in material prosperity and grant them more freedoms (first of all, freedom of speech and freedom of choice). The political “machine” created by Soviet power worked successfully for many years: thanks to this “machine” the Great Patriotic War was won; the Soviet economy owes its prosperity in the postwar years to this “machine”; and thanks to precise planning and the key role of the state in the governance of the country, the Soviet Union was able to become one of the two leading powers in the world. But this “machine” worked effectively to strengthen the statehood, rather than meet the social needs of the population. The Soviet system turned out to be rigid, the bureaucratic apparatus of the ruling elite did not manage to adapt to the conditions when Russian society became “tired” of the dullness and monotony of the Soviet ideology and the values of capitalism and democracy of the Western world started to penetrate Russian society. “The Soviet leadership generally underestimated narrowmindedness of the narrow-minded individual. The Soviet people were treated to everything that was wholesome in all respects, but they wanted something that was delicious, tart, effervescent, and bright”24.

The tragedy of the collapse of the USSR does not consist in the fact that Americans successfully implemented a strategic plan to eliminate a geopolitical rival; the tragedy is the fact that within the very political elite of the Soviet Union there were people who were willing to implement that plan, and this is already an internal problem of the system, rather than a problem with “foreign enemies”.

Today one can speak about the capacity of the Soviet Union only in the subjunctive mood. Actually, Russia is far inferior to its geopolitical competitors (USA, Japan, Western Europe) in terms of economic development25.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and, more broadly, of the whole Soviet life was rather an external than internal phenomenon. We somehow forget that the Soviet Union collapsed virtually at the peak of its military and industrial might, more precisely, at a stagnant slide from that peak. And that breakout was perceived by a vast majority of citizens with delight and enthusiasm, and was welcomed with stormy and prolonged applause. The overthrow of the “sovok” (a Russian slang word that denotes the Soviet Union, Soviet system or a Soviet citizen; the word sounds like “Soviet” but means “dustpan” in normal language. – Translator’s note), judging by all these attitudes, was neither a conspiracy, nor a coup; it was a truly nationwide cause. Granted, it involved conspiracy, and revolution, and betrayal, but without people’s support, and not even support but direct participation, it would have failed.

(Source: Voevodina T. Chego sovkam v sovke ne khvatalo [What Soviet people did not have in the Soviet Union]. Literaturnaya gazeta [Literary newspaper], 2015, no. 33, August 26 – September 01.)

“The instinct of state might” which, according to Berdyaev, characterized Russian society in the 19th – 20th centuries, is inherent in the modern Russian society as well. It “woke up” together with national identity, which “is the basis of the Russian civilization project, is deeply rooted and widespread in people’s minds, although it was as if in a “sleeping”, latent condition”26. The reason for this “awakening” can be found in events such as Vladimir Putin’s speeches in Munich (2007), at the meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club (2013), and after the Russian team’s successful performance at the Olympic Games in Sochi (2014), accession of Crimea and Sevastopol to the Russian Federation (2014), and after the effective participation of Russia in the Syrian conflict” (2013, 2015).

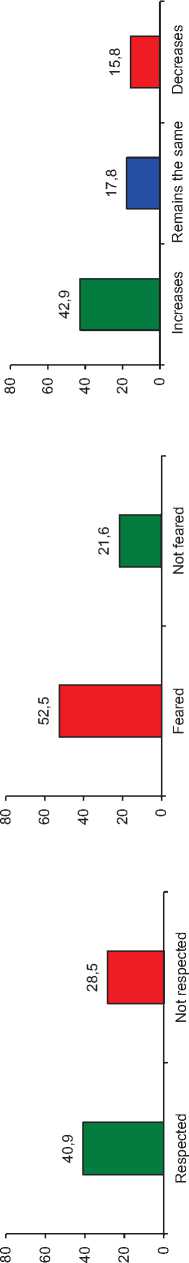

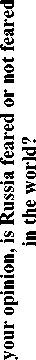

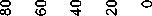

The results of sociological research help answer the question of what is meant by “the instinct of state might” and why this “state might” exists today in an “instinctive” form. According to VTsIOM, 75% of Russians believe that Russia has considerable influence on the state of affairs in the world; as many (75%) believe that Russia at present is a great power or it can become one in the next 15–20 years27. In people’s opinion, Russia is feared (53%) and respected (41%) in the world, and its impact on the global community is growing (43%). 68% of Russians (according to Levada-Center) “are proud of today’s Russia” (the opposite view is expressed by only 24%; Insert 1 )28.

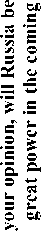

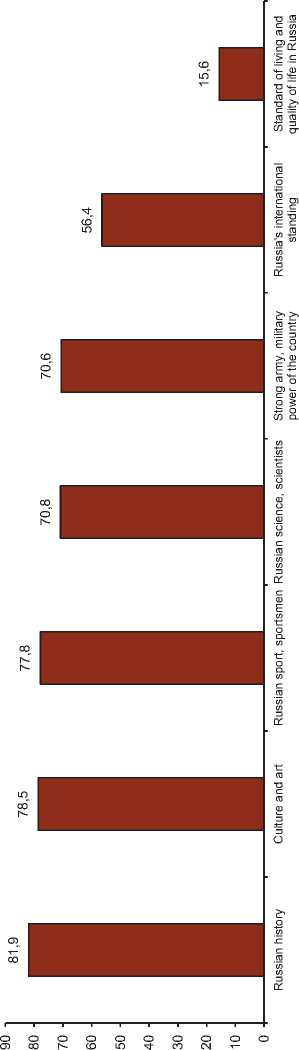

However, the current standard of living and quality of life are not among the things that Russians are proud of in their country, rather it is Russian history, science, culture, army, and sport (20–40% according to Levada-Center, and 70–80% according to ISEDT RAS29). It is not the life in Russia that is the source of this pride, but Russia’s previous heritage, which, of course, will stay forever in the memory of generations: classics of Russian and world literature, music, painting; the first flight of man in space, the victory in the Great Patriotic War, sport achievements of the USSR national team, etc.

Not more than 16% of Russians are proud of their current life in the country (according to ISEDT RAS); 12% are proud of their fellow countrymen (according to Levada-Center), 5% are proud of Russia’s economic achievements, 5% are proud of Russian education system, and 2% are proud of Russian healthcare system (Insert 2) .

An acute need for social justice is a feature that Russia had in the beginning of the 20th century and that it has retained in the early 21st century. Historians indicate that at the end of the 19th century “the remnants of feudalism: political injustice, absence of the labor law, arbitrary rule of masters, and widespread abuse weighed upon the workers and peasants alike... These and other facts prove that Russian society experienced an acute shortage of social justice”30.

Today, the need “to live in a more just and reasonably ordered society” ranks third in a list of the most important dreams of Russians (33%). The first one is the need “to live in wealth, to be able to spend money

“without counting the kopecks” (40%); the second – the dream about “good health” (33%)31.

The desire for social justice can also be seen in the results of regional sociological studies. Thus, according to ISEDT RAS data as of June 2016, 57% of people believe that “modern Russian society is arranged unfairly”; the opposite opinion is shared only by 11% of people321.

Thus, although in 100 years that passed since the events called “the Russian Revolution” Russian society and the world situation faced qualitative changes, they still have general conceptual features that point to a possibility of revolution today.

Russian philosopher and sociologist Pitirim Sorokin notes that revolution “is not a random event” and it is caused by two factors33:

-

1 . The first one relates to the driving forces behind revolution masses: “An immediate prerequisite for any revolution has always been the increase in the number of suppressed basic instincts of the majority

-

2 . The second factor relates to the response of the authorities: “...A revolutionary explosion requires that the social groups that guard the existing order did not have a sufficient arsenal of tools to suppress the destructive encroachments from below... The atmosphere of pre-revolutionary eras always amazes the observer with the impotence of the authorities and degeneration of the ruling privileged classes. They are often not able to perform elementary administration functions, not to mention resisting the revolution using force”.

of the population, and the inability to satisfy them even to the minimum extent”.

“If both conditions – the pressure “from below” and the weakness of “the top” – match, then revolution becomes inevitable”.

Of course, unlike the pre-revolutionary Russian society, modern society has a constructive attitude toward the authorities34, so today we are not talking about “mass repressions” and other means of “suppressing the destructive encroachments”. However, the signs of the first of the two causes of revolution mentioned by Pitirim Sorokin are obvious – basic instincts, which for Russians comprise a sense of social justice and an opportunity to live “without counting the kopecks” 35 , do not find their satisfaction.

-

34 For example, researchers have noted that members of the middle class “are convinced of the futility of revolutionary change. This segment of society is not just ready to cooperate with the government, it is largely loyal to the authorities, ready to agree with them and obey their will, and work together to change things for the better” (source: Skorobogatyi, P. Trevozhnyi i loyal’nyi [Alarming and loyal]. Zhurnal “Ekspert” [Journal “Expert”], 2015, no. 45, November. Available at: http://expert.ru/expert/2015/45/ trevozhnyij-i-loyalnyij/).

-

35 Gorshkov M.K., Krumm R., Tikhonova N.E. (Eds.). O chem mechtayut rossiyane: ideal i real’nost’ [What the Russians dream of: ideal and reality]. Moscow: Ves’ Mir, 2013. P. 22.

Insert 1

Insert 2

Source: ISEDT RAS data, June 2016. Question: “Could you say that you are proud of…?”

Historical parallels drawn between the Russia of the late 19th – early 20th century and the Russia of the beginning of the 21st century will inevitably lead to reflections on the relevance of issues related to public administration efficiency. The tension of the current situation in the country and in the international arena, as well as 100 years ago, dictates special requirements to the current government and to the political elite. Our history teaches us that a protracted and growing nature of unsatisfied needs of the population leads to tragic consequences for the current government; this is why the disregard of these needs, and the lack of effectiveness in solving these problems are unacceptable; this, in the first place, brings to the fore the problems and prospects of the Russian parliamentary system.

On the difficult path toward the development of parliamentarism

The beginning of the 20th century in the Russian history was marked not only by the events of the Russian Revolution, but also by the formation of the institution of parliamentary control36. However, despite certain steps that the Emperor had taken in the direction of limiting the power of the monarchy, the revolutionary events of 1905– 1917 could not be avoided, and it proved a simple truth: no institutions and laws that aim to develop parliamentarism are able to perform their task if the system of public administration has not created favorable conditions for their effective functioning and if it does not respond to key challenges of national security.

The establishment of the State Duma was a forced measure that Nicholas II had to implement due to the critical social situation of that time. Therefore, during the disputes between the Duma and the members of the Government, the Emperor regularly made decisions in favor of the latter, and dissolved the Duma several times37. As for the government, from the very beginning, it was swamping the State Duma deputies with the so-called “legislative noodles” – current trifle matters that have no political importance either for the authorities or the country.

In turn, the Duma, fearing another dissolution, was loyal to the Government. In addition, during the First World War, domestic issues in Russia receded into the background; Duma meetings were held under the traditional slogan “We fight until we win”, and only the last convening of the Duma under the pressure of “economic chaos, the aggravation of nationwide crisis in the country during the war, which put the country on the brink of starvation and economic exhaustion, having caused antiwar sentiment among the masses” was forced to update the internal agenda of life in the country, though it was done “amidst uncertainty, confusion and division”38.

In the end, whatever the causes of inefficiency of performance of State Duma deputies in the Russian Empire in 1905–1917, they failed to fulfil their main task of ensuring the implementation of laws aimed to satisfy the priority need of the population in social justice. Historians note that “after the State Duma was established in Russia, the representatives of the liberal bourgeoisie enthusiastically declared that Russia would have a Parliament at last, and from that day on the country would enter the era of parliamentarism. The bourgeois-liberal camp betrayed the revolutionary movement and was quite satisfied with the autocracy with the State Duma. The bourgeoisie achieved what they had desired. The autocracy as an essential barrier against people’s revolution was preserved”39. Russia’s public administration system in the early 20th century was characterized by “mutual economic interest of the monarchy,

In vain did the liberal bourgeoisie believe that with the establishment of the State Duma Russia had got itself a Parliament. The Duma did have some external features of the Parliament. It could direct requests to the government – a reorganized Council of Ministers – and to its individual members. However, ministers could either consider those requests or pay no attention to them. The government had no liability to the State Duma. The ministers were appointed and dismissed by the Tsar, they did not report to the Duma and did not depend on it, despite the fact that the very reorganization of the Council of Ministers was connected to the establishment of the Duma.

The State Duma even made attempts to pass a no-confidence motion against the government. The act of no confidence from the State Duma received no response of the government, it just paid no attention to it. There were even cases when after the Duma had criticized certain officials for their abuse of power, the Tsar, who hated the Duma, promoted those officials. Thus the Tsar showed that he paid no regard to the Duma.

(Source: Istoriya otechestvennogo gosudarstva i prava: uchebn. posob. [History of the Russian state and law: textbook]. Available at:

the landlords and the bourgeoisie” 40; this interest determined the outcome for the domestic political and social situation in the country: a rise of popular discontent without an adequate response from the authorities made the events of 1905 and 1917 inevitable.

By and large, history repeated itself 70 years later: the unwillingness of the ruling elites to hear the voice of the people became one of the inner levers that facilitated the collapse of the Soviet Union. People’s growing need for information diversity was not satisfied; the needs of the intelligentsia to manifest freedom were suppressed. “Probably, having understood what was necessary, one could create an information environment that would correspond to people’s “wish list”. After that, one could use this environment to carry out Soviet propaganda. But in order to realize all this and then set the appropriate task and implement it, it was necessary to have people with vision and imagination, and there were none of such people among the leadership”41.

Today, generally speaking, the government faces the same challenges as 100 years ago: there is a growing need for social justice and improvement of the dynamics of the quality of life. Moreover, experts point out the lack of efficiency in the work of the Russian Government in recent years, the lack of consistency in the actions of ministers, and the fused interests of the ruling elite and representatives of the oligarchic clan42.

The President’s struggle against “the comprador forces, whose interests and assets are within the sphere of influence of the

“collective West”43, has been going on for more than 15 years (since the beginning of Vladimir Putin’s first presidency). This struggle is becoming increasingly uncompromising and tough4421, but it has not resulted in any significant breakthrough so far. Therefore, the necessity to improve the effectiveness of parliamentary control in the system of public administration in modern Russia is no less important than it was in the Russian Empire at the beginning of the 20th century and in the Soviet Union in the late 1980s. “Without real elections, without real opposition, and without parliamentary control over the executive power, it is impossible to establish a competitive administrative environment and build an effective management system in the 21st century.” 4522

September 18, 2016, Russia will hold the election of the deputies of the State Duma of the Russian Federation of the 7th convocation. The previous State Duma has done much to enhance the efficiency of the mechanism of parliamentary control (in particular, the Law “On parliamentary control” was adopted, which expanded the supervisory powers of the Accounts Chamber, etc.), but, by and large, modern parliamentarism in Russia has the same flaw as 100 years ago: the existence of a legal and institutional framework of the parliamentary system does not guarantee its effective functioning, i.e. does not guarantee the possibility to address key challenges of national security on a system-wide basis.

Against the backdrop of international political events that were unfolding during the period of work of the State Duma of the 6th convocation (the Ukrainian and Syrian conflicts, accession of Crimea and Sevastopol to the Russian Federation, international sanctions, deployment of the hybrid warfare), the “merging of the parliamentary opposition with the ruling party” took place. According to experts, “in such situations, the effect of consolidation around the flag is automatic. The parliamentary opposition did not have other options, except joining this patriotic parade... As a result, the State Duma has ceased to perceive adequately the critical assessments from without”462.

The situation in the international political arena largely dictated the key laws that marked the work of the State Duma of the 6th convocation472. They were in line

-

46 Vinokurova E. Palata nomer shest’: glavnoe, chem zapomnitsya ukhodyashchii sozyv Gosudarstvennoi Dumy Rossii [Ward number six: the most important things by which the outgoing State Duma of Russia will be remembered]. Internet-gazeta Znak ot 24.06.2016 [Internet Newspaper “Sign”, issue of June 24, 2016]. Available at: https://www . znak.com/2016-06-24/glavnoe_chem_zapomnitsya_ uhodyachiy_sozyv_gosudarstvennoy_dumy_rossii (an opinion of political scientist A. Gallyamov).

-

47 Among them: Dima Yakovlev Law, the Law on nonprofit organizations – “foreign agents”, the Law on direct elections of governors, the Law on the introduction of the “Platon” system, etc.

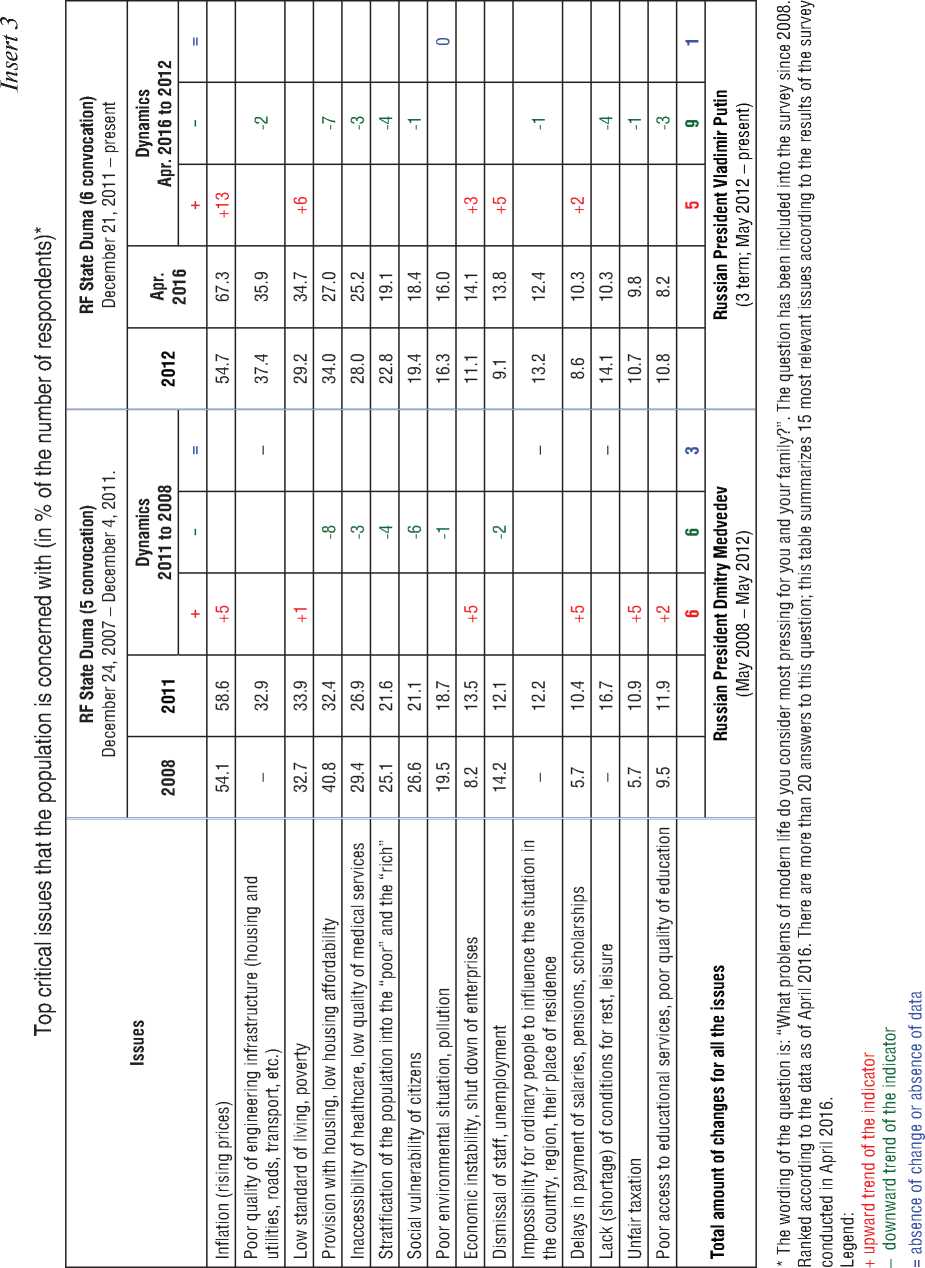

with issues discussed in society and in the media, but most of them were not related to the major issues that people are concerned about – inflation, decline in the standard of living and quality of life (Insert 3) .

Accounts Chamber experts regularly criticize the Government, but their opinion is not taken into consideration. The approval of the Cabinet of Ministers by the State Duma is held through a single list that initially brings to naught their personal responsibility.

The most telling indicator of efficiency of work of the State Duma can be the level of people’s trust in it. Experts at the Institute of Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences point out that “in Russian society there is a request to change the composition of State Duma officials. Russians are no longer satisfied with the current alliance of party functionaries, businessmen and the so-called “media personalities” (athletes, artists, entertainers) existing in the Duma... Russians would like to see the next Parliament, first, more professional, and second, more adequately representing the major social groups and strata of society and, thirdly, in the new Parliament there should be a place for civil activists and well-known public figures, many of which have already gained experience and political “weight”48.

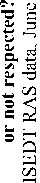

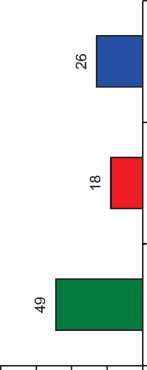

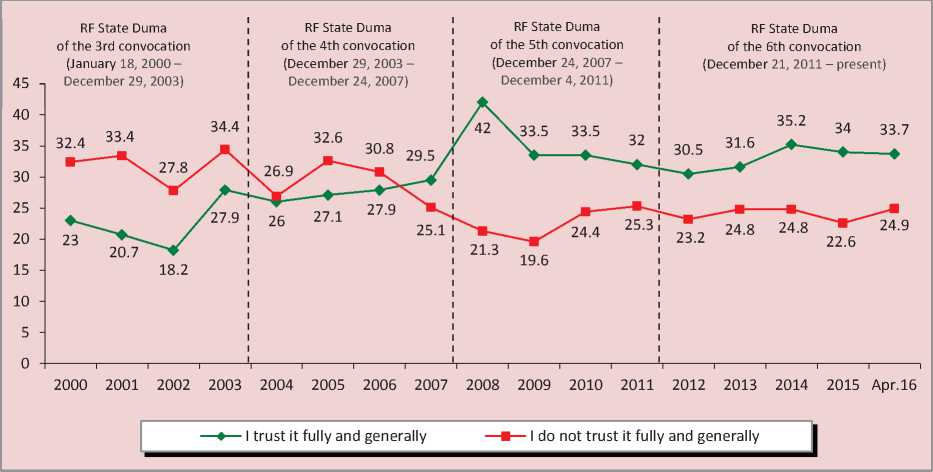

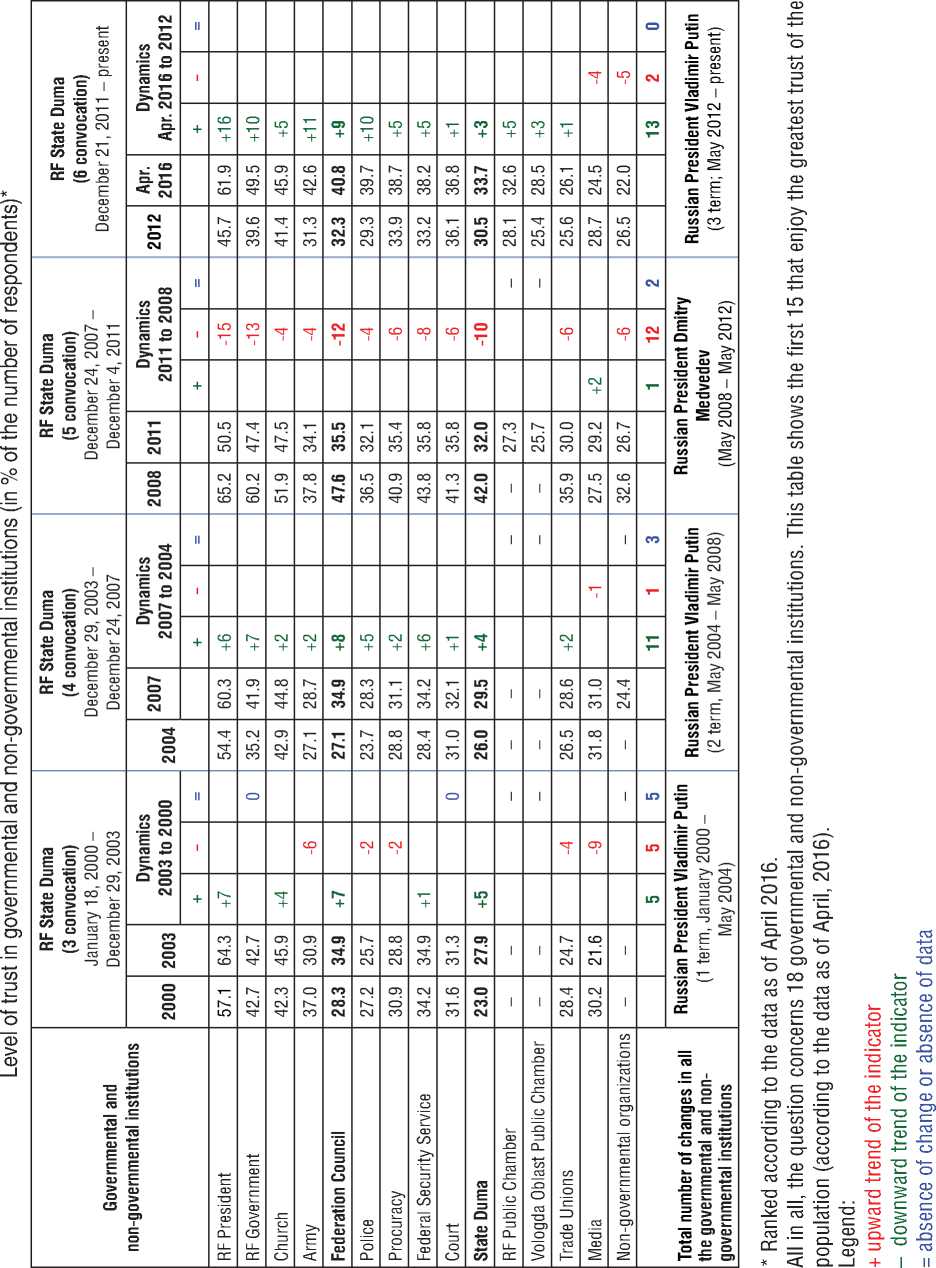

People’s skeptical attitude toward the activities of the deputies is confirmed by the results of regional sociological studies. According to ISEDT RAS, the trust in the deputies after a sharp drop in 2009 (from 42 to 34 p.p.) remained at the same level (Fig. 1) . The new Duma of the 6th convocation has not introduced any changes in this dynamics. Among all the state institutions, the State Duma has the lowest level of trust among the population, and this is registered throughout the period of 2000 to 2016; that is, during the last three compositions of the deputies. Judging by the data for April 2016, 62% of the people trust Russian President, 50% – the Government, 41% – the Federation Council, 34% – the State Duma, 19% – political parties (Insert 4) .

Thus, the key tasks that were set out before the deputies of the State Duma of the 6th convocation (and, more broadly, before the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation)49, have not been resolved. In

Figure 1. Dynamics of trust in the State Duma of the Russian Federation (as a percentage of the number of respondents)

general, it will be up to the deputies of the 7th convocation to solve them, and the longer the solution is delayed, the more obvious the process of growth of social tension in the country will be. Despite the fact that the share of Russians who are ready to take part in protest actions is, according to various estimates, about 20%5025, it would be a strategic mistake to ignore the existence of social tensions at the latent level, since it is extremely difficult to forecast revolutionary changes in society; for the authorities and historians, the changes become obvious only “after the fact”, when it is already impossible to do anything to improve the situation.

In lieu of a conclusion. Before the election to the State Duma of the seventh convocation, September 18, 2016...

-

50 The proportion of people who consider mass protests possible, according to VTsIOM (as of July 2016), is 21%; according to ISEDT RAS (as of August 2016) – 18%.

A brief historical overview leads to the conclusion that the Russian Empire at the turn of the 20th century, the Soviet Union in the 1980s, and the Russian Federation in the early 21st century have much in common. Historical parallels can be drawn in the socio-economic development of the state (lagging behind Western countries), and in the specifics of social consciousness (“the instinct of state might”), and the efficiency of public administration (the inability to fulfill the needs of the population in social justice and in enhancing the quality of life).

Furthermore, like 100 years ago, Russia has to deal with the domestic socioeconomic agenda in very difficult conditions of the international political situation, where the country plays a key role and, therefore, cannot stand aside from global processes.

Insert 4

At the beginning of the 20th century, the tsarist monarchy was unable to bring public administration to such a level that its effectiveness could be seen by wide layers of population. The basic needs of people were not satisfied, and this led to the revolutionary events that radically changed not only Russia itself, but the whole world.

The same thing happened in the late 1980s: the system of public administration was efficient in coping with the task of strengthening the state and enhancing its industrial and military power; but it failed to consider timely the growing needs of the population that demanded an increase in their well-being and granting of democratic freedoms; all these factors led to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Today, government authorities again face the same problems, and in order to avoid the mistakes of the past, they will have to take more effective action than 100 and 30 years ago. “One of our key lessons today is that the problem of Russia is the simultaneous existence of unsatisfied democratic and social demands that were long overdue a hundred years ago. This is a reason for the tragedy”512.

The approaching State Duma election can (and, in our opinion, should) become a turning point in enhancing the effectiveness of public administration. At least those tasks

-

51 Dugin A.G. Segodnya Rossii neobkhodima konservativnaya revolyutsiya. A. Dugin v programme Vitaliya Tret’yakova “Chto delat’?”, kanal “Kul’tura”, VGTRK, 6 iyunya 2005 g. [Today, Russia needs a conservative revolution. A. Dugin in the program of Vitaly Tretyakov “What to do?”, the channel “Culture” VGTRK, 6 June 2005]. Informatsionno-analiticheskii portal “Evraziya” [Information-analytical portal “Eurasia”]. Available at:

It is true that now there is a prerevolutionary situation in Russia. The orange revolution, which began in the autumn of last year, is now just frozen and hidden, but it has not dissolved. It was the same with the revolution of 1905; it, too, was hiding, and then it broke loose.

(Source: Prokhanov A.A. Esli by ne bylo Oktyabr’skoi revolyutsii, Gitler zavladel by vsei Evropoi [If it were not for the October revolution, Hitler would have taken possession of the whole Europe]. Gazeta “Komsomol’skaya Pravda” [Newspaper “Komsomol truth”], 2012, November 06 [e. RES.]. Available at: http://www. .

to be solved by the Federal Assembly and the State Duma of the 6th convocation have not been resolved, and the relevance of bringing the Russian parliamentary system to a qualitatively new stage in its development continues to grow.

However, there is another possible scenario. If in the coming months of political life (especially after the election of a new composition of the State Duma) there are no significant changes in the system of government, if Russian people continue to experience increasing demand for social justice and improving the quality of life, then social tensions in the country could increase significantly and this could affect the overall psychological atmosphere in which the presidential election will take place in 2018. Ultimately, the efficiency of all the chambers of the Federal Assembly today can become a key factor in the presidential election.

Finding solutions to priority tasks that the Federal Assembly and, in particular, the

State Duma of the Russian Federation, have to deal with requires that two conditions are observed simultaneously:

first, the presence of political will, because the roots of the problems of Russian parliamentarism go deep into the structure of the system of public administration prevailing in the last two decades. The merged interests of the political elite and the big oligarchy exist at all levels of the management system, and they systematically and comprehensively impede the implementation of national interests. It is impossible to find a solution to this problem without making tough domestic political decisions;

The years 1905 and 1917 predetermined the century that we lived through. But the prelude and the epilogue are two different things. Granted, the problems are the same today, but at that time they stood before the beginning of their solution, and today they stand after its ending; at that time it was a creative upsurge with all the attendant excesses of the revolution, today it is the period of decadence, decomposition, weakness and so on. There are similarities between today and that day, and in general, today’s questions are not solved again, but all these questions of 1905, over a hundred years, during the 70 years of the Soviet regime, were solved, and after them there emerged other issues, and today we are back...

second, an integrated approach to improving the efficiency of public administration. History shows that adopting laws and establishing any special institutions does not guarantee the efficiency of public administration; this can be said about any of the branches of government. The key task is to ensure that these laws and institutions actually work, and it is a strategic objective not only for the State Duma, but also for the President, who has assumed personal responsibility for dealing with domestic issues in the country52.

Thus, the negative historical experience of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union puts before the government and the President of the Russian Federation the urgent question that public administration should create conditions facilitating the comprehensive and systematic solution of key challenges of national security at all stages of development of the Russian statehood.

What will be the response of the President to the growing need for improving the quality of life and social justice in society? To what extent will Russia’s historical experience in ensuring the functioning of the system of administration be taken into account? Today these questions are becoming a cornerstone of national security, because for Russian society they have acquired the nature of lingering expectations. The first months of work of the State Duma of the 7th convocation will have to show determination in the actions of a new political elite in achieving national interests and first and foremost – in the implementation of the main needs of the population, which will be essential for ensuring national security and subsequent competitiveness of Russia in the 21st century without twists and turns like those in the history of the 20th century.

Список литературы The ruling elites: a problem for Russia's national security

- Berdyaev N.A. Istoki i smysl russkogo kommunizma . Paris, 1955. 224 p.

- Vishnevskii A.V. Serp i rubl': konservativnaya modernizatsiya v SSSR . Moscow: OGI, 1998. 432 p..

- Glazyev S.Yu. Prichiny degradatsii ekonomiki . Informatsionno-analiticheskoe izdanie “Internet protiv teleekrana” . Available at: http://www.contrtv.ru/common/4407/.

- Gorshkov M.K. “Russkaya mechta”: opyt sotsiologicheskogo izmereniya . Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya , 2012, no. 12, pp. 3-11..

- Gubanov S.S. Sistemnyi krizis i vybor puti razvitiya Rossii . Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz , 2015, no. 2 (38), pp. 23-41..

- Gubanov S.S. Sotsial'nyi kontrakt vlasti s syr'evym oligarkhatom: rost bez razvitiya: interv'yu na radio “Govorit Moskva” ot 18.03.2009 . Informatsionno-analiticheskaya sluzhba “Russkaya liniya” . Available at: http://ruskline.ru/analitika/2009/03/19/social_nyj_kontrakt_vlasti_s_syr_evym_oligarhatom_rost_bez_razvitiya/.

- Dugin A.G. Segodnya Rossii neobkhodima konservativnaya revolyutsiya. A. Dugin v programme Vitaliya Tret'yakova “Chto delat'?”, kanal “Kul'tura”, VGTRK, 6 iyunya 2005 g. [Today, Russia needs a conservative revolution. A. Dugin in the program of Vitaly Tretyakov “What to do?”, the channel “Culture” VGTRK,

- June 2005]. Informatsionno-analiticheskii portal “Evraziya” . Available at: http://evrazia.org/modules.php?name=News&sid=2478.

- Wallerstein I., Collins R., Mann M., Derluguian G., Calhoun C. Est' li budushchee u kapitalizma?: sbornik statei . Moscow: Institut Gaidara, 2015. 320 p..

- Zheleznyak S.V. Novye informatsionnye tekhnologii povyshayut otkrytost' Gosdumy . Ofitsial'nyi sait partii “Edinaya Rossiya”. Novosti ot 09.04.2012 . Available at: http://er.ru/news/80640/.

- Kagarlitskii B. Kto podavit vosstanie elit . Ekspert , 2016, no. 30-33, pp. 50-53..

- Kashnikov B.N. Ideya spravedlivosti v teorii i praktike russkogo terrorizma kontsa 19-go -nachala 20-go veka . Rossiiskii nauchnyi zhurnal , 2008, no. 3 (4), pp. 47 -57..

- Quiggin J. Zombi-ekonomika. Kak mertvye idei prodolzhayut bluzhdat' sredi nas . Translated from English by A. Gusev. Under the scientific editorship of A. Smirnov. Moscow: Vysshaya shkola ekonomiki, 2016. 272 p..

- Lapin N.I. Gumanisticheskii vybor naseleniya Rossii i tsentry vnimaniya rossiiskoi sotsiologii . Sotsis , 2016, no. 5, pp. 23-34..

- Naryshkin S.E. Demokratiya i parlamentarizm . Rossiiskaya gazeta , 2012, no. 5750 (77), 9 September. Available at: https://rg.ru/2012/04/09/narishkin.html.

- Natsional'naya gordost': press-vypusk Levada-Tsentra ot 30.06.2016. Available at: http://www.levada.ru/2016/06/30/natsionalnaya-gordost/.

- Gorshkov M.K., Krumm R., Tikhonova N.E. (Eds.). O chem mechtayut rossiyane: ideal i real'nost' . Moscow: Ves' Mir, 2013. 400 p..

- Petrov Yu. Rossiya v 1913 godu: ekonomicheskii rost . Nauka i zhizn' , 2014, no. 7, pp. 3-13..

- Rossiiskoe obshchestvo vesnoi 2016-go: trevogi i nadezhdy: informatsionno-analiticheskoe rezyume po itogam obshcherossiiskogo sotsiologicheskogo issledovaniya . Moscow, 2016. 32 p..

- Rossiya -velikaya nasha derzhava: press-vypusk VTsIOM ot 10.06.2016. Available at: http://wciom.ru/index.php?id=236&uid=115728.

- Skorobogatyi, P. Trevozhnyi i loyal'nyi . Zhurnal “Ekspert” , 2015, no. 45, November. Available at: http://expert.ru/expert/2015/45/trevozhnyij-i-loyalnyij/.

- Stenogramma vystupleniya V.V. Putina na zasedanii Mezhdunarodnogo diskussionnogo kluba “Valdai” 22 oktyabrya 2015 g. . Ofitsial'nyi sait Prezidenta RF . Available at: http://www.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/50548.

- Stenogramma vystupleniya V.V. Putina na Myunkhenskoi konferentsii po voprosam politiki bezopasnosti fevralya 2007 g. . Ofitsial'nyi sait Prezidenta RF . Available at: http://www.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/24034.

- Stepanov A. Poteri naseleniya Rossii v Pervoi mirovoi voine . Zhurnal “Demoskop Weekly” , 2014, no. 623-624. 15-31 December. Available at: http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/2014/0623/tema01.php.

- Ukaz Prezidenta Rossiiskoi Federatsii ot 31 dekabrya 2015 goda No. 683 “O Strategii natsional'noi bezopasnosti Rossiiskoi Federatsii” . Rossiiskaya gazeta , 2015, 31 December. Available at: http://www.rg.ru/2015/12/31/nac-bezopasnost-site-dok.html.

- Fadeev V.A. Naiti istinnye tseli . Zhurnal “Ekspert” , 2016, no. 6 (974), 8-14 February, pp. 12-19..

- Sztompka P. Sotsiologiya sotsial'nykh izmenenii . Translated from English under the editorship of V.A. Yadov. Moscow: Aspekt Press, 1996. 415 p..

- Za derzhavu obidno! Tamozhnya -delo tonkoe (mnenie politologa F. Biryukova) . Gazeta «Zavtra» , 2016, 4 August, no. 31 (1183), p. 5

- Prichiny ekonomicheskikh protivorechii i sopernichestva vedushchikh stran nakanune Pervoi mirovoi voiny . Baza dannykh “Mir znanii” . Available at: http://mirznanii.com/info/1-prichiny-ekonomicheskikh-protivorechiy-i-sopernichest-va-vedushchikh-stran-nakanune-pervoy-mirovoy-_278616

- Ivashov L. Spodruchniki i nasledniki Reigana . Literaturnaya gazeta , 2016, no. 31, August 3. Available at: http://www. lgz.ru/article/-31-6562-03-08-2016/avgust-1991/

- Sotsial'nyi kontrakt vlasti s syr'evym oligarkhatom: rost bez razvitiya: interv'yu S.S. Gubanova na radio “Govorit Moskva” ot 18.03.2009 . Informatsionno-analiticheskaya sluzhba “Russkaya liniya” . Available at: http://ruskline.ru/analitika/2009/03/19/social_nyj_kontrakt_vlasti_s_syr_evym_oligarhatom_rost_bez_razvitiya/

- Ofitsial'nyi sait Prezidenta RF . Available at: http://www.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/24034

- Kholmogorov E. O nereshennoi probleme sotsializma . Gazeta “Zavtra” , 2016, no. 17 (1169), April 28, p. 3

- Putin V.V. Rech' na zasedanii Mezhdunarodnogo diskussionnogo kluba “Valdai” 22.10.2015 . Ofitsial'nyi sait Prezidenta RF . Available at: http://www. kremlin.ru/events/president/news/50548

- Revolyutsiya 1917-go radikal'no izmenila ves' mir: interv'yu direktora Instituta globalizatsii i sotsial'nykh dvizhenii B. Kagarlitskogo informatsionnomu portalu Pravda.ru . Available at: http://www.pravda.ru/news/society/07-11-2013/1181206-revolution-0/

- Pervaya Vseobshchaya perepis' naseleniya Rossiiskoi Imperii 1897 g. . Ed. by N.A.Troinitskii. Volume 1. Obshchii svod po Imperii rezul'tatov razrabotki dannykh Pervoi Vseobshchei perepisi naseleniya, proizvedennoi 28 yanvarya 1897 goda . Saint Peterburg, 1905. Table 8. Distribution of population by estates and conditions

- Padenie Konstantinopolya (29 maya 1453 goda) . Sait Khrama Zhivonachal'noi Troitsy na Vorob'evykh gorakh . Available at: http://hram-troicy. prihod.ru/articles/view/id/1166651

- Volchkova N.N. Parlamentskii kontrol' v Rossii: istoricheskii aspekt . Analiticheskii portal “Otrasli prava” . Available at: http://отрасли-права. рф/article/13117

- Zakonodatel'naya deyatel'nost' IV Gosudarstvennoi Dumy . Informatsionnyi portal “Rossiiskaya Imperiya. Istoriya gosudarstva rossiiskogo” . Available at: https://www.rusempire.ru/rossijskaya-imperiya/gosudarstvennaya-duma-ri/gduma-ri-4-sozyva/45-zakonodatelnaya-deyatelnost-iv-gosudarstvennoj-dumy.html

- Istoriya otechestvennogo gosudarstva i prava: uchebn. posob. . Ed.by O.I. Chistyakov. 1999. Part. 2. 544 p. Available at: http://www.bibliotekar.ru/teoria-gosudarstva-i-prava-6/184.htm

- Tsarskaya Rossiya v nachale XX veka . Federal'nyi portal Protown.ru . Available at: http://www. protown.ru/information/hide/5967.html

- Voevodina T. Chego sovkam v sovke ne khvatalo . Literaturnaya gazeta , 2015, no. 33, August 26 -September 01

- Glazyev S.Yu. Pravitel'stvo gotovo sdat' vlast' Zapadu . Novostnoi portal Newsland.com. Novosti ot 25.06.2016 . Available at: https://newsland.com/user/4296757178/content/sergei-glazev-pravitelstvo-gotovo-sdat-vlast-zapadu/5310381

- Boldyrev Yu.Yu. Pravitel'stvo provodit politiku “nichegonedelaniya” (interv'yu Yu.Yu. Boldyreva Agentstvu biznes-novostei ot 24.03.2015 . Ofitsial'nyi sait Agentstva biznes-novostei . Available at: http://abnews.ru/2015/03/23/pravitelstvo-provodit-politiku-nichegonedelaniya-boldyrev/

- 2015 god byl upushchen . Gazeta “Vedomosti” , 2016, February 03. Available at: http://www.vedomosti.ru/economics/characters/2016/02/03/626586-2015-god-bil-upuschen

- Gordeev A. Spor Kudrina s Putinym. Rossiya na pereput'e . Gazeta “Zavtra” , 2016, no. 22 (1174), June 02, p. 4.

- Ilyin V.A. Vybory v Gosudarstvennuyu Dumu-2016. Ekonomicheskaya politika Prezidenta v otsenkakh naseleniya . Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz , 2016, no. 3 (45), p. 24.

- Vinokurova E. Palata nomer shest': glavnoe, chem zapomnitsya ukhodyashchii sozyv Gosudarstvennoi Dumy Rossii . Internet-gazeta Znak ot 24.06.2016 . Available at: https://www. znak.com/2016-06-24/glavnoe_chem_zapomnitsya_ uhodyachiy_sozyv_gosudarstvennoy_dumy_rossii (an opinion of political scientist A. Gallyamov)

- Prokhanov A.A. Esli by ne bylo Oktyabr'skoi revolyutsii, Gitler zavladel by vsei Evropoi . Gazeta “Komsomol'skaya Pravda” , 2012, November 06 . Available at: http://www. vologda.kp.ru/daily/25979/2913360/