The rustic bunting Emberiza rustica on the mid-Anadyr river

Автор: Kretchmar E.A.

Журнал: Русский орнитологический журнал @ornis

Статья в выпуске: 123 т.9, 2000 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140149113

IDR: 140149113

Текст статьи The rustic bunting Emberiza rustica on the mid-Anadyr river

Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Faculty of Biology and Soil, Saint-Petersburg University, Universitetskaya nab., 7/9, Saint-Petersburg, 199034, Russia

Received 10 November 1995

The considerable interest to the breeding biology of the rustic bunting Emberiza rustica is understandable for the region close to the Northern Primorie that is considered the center of origin for Emberiza genus in Eurasia (Duncker 1912). Besides, this area is located near the Bering Strait that is traditionally regardered as exchanging bredge between the palearctic and nearctic faunas.

The rustic bunting inhabits the taiga and southern wood-tundra from southeastern Finland (Pulliainen, Saari 1989) on the west to the mid-Anadyr River on the east (Spangenberg, Sudilovskaya 1954). Low borders of its breeding range stretch to southern edge of taiga (Vorob’ev 1963; Portenko 1960). The breeding ecology data for this large area are available only for the western regions (Rymkevich 1979; Pulliainen, Saari 1989). These data are probably not sufficient for the understanding of the ecology of the species in primary natural nesting conditions. Undoubtedly, the information about the rustic bunting’s biology in different parts of its range is interesting for the systematic and mi-croevolutionary comparisons.

Some brief data on the nesting ecology for rustic bunting in the eastern regions were included in the faunistic and regional reviews (Portenko 1939, 1960; Kretchmar et al. 1991) that determined author’s aspiration to study it more fully. New data from this region are interesting for the correct comprehension of the breeding biology in the place that are anthropogenized insignificantly in comparison with western territories. The article is concerned with the breeding biology of the rustic bunting at the region difficult of access at the North-East of Asia.

Study area

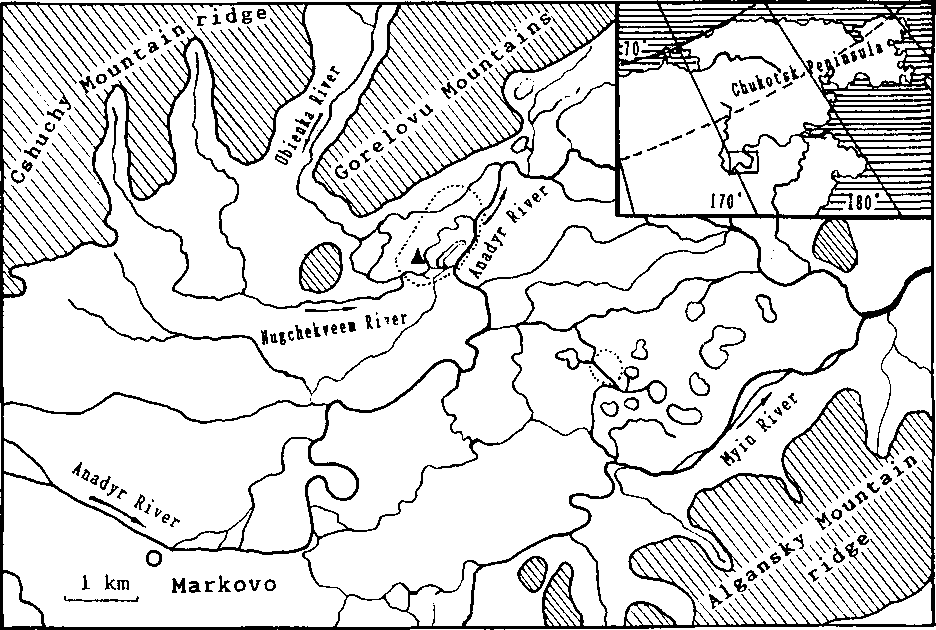

The region of the middle reaches of the Anadyr River consists of a few intermittent landscape types that are crossed by the great number of channels, small rivers, sloughs and arms of the Anadyr and Myin rivers. Two basic landscape types which cover most of the mid-Anadyr plain are especially deserving of a short description.

Another basic landscape type for this area is the upland wood-tundra (15-30 m above the sea level) with a moss-lichen cover on the ground and shrub-pine (P/hz/s pumila) with sedge pings (Carex spp.) as a basic plant components. Little birches, low alders, red bilberries Vaccinium vitis-idaea and Labrador tea Ledum decumbens also grow there. Hereafter this type of landscape will be mentioned as “shrub-tundra”.

Fig. 1. Location of the study area (within the dotted-line border) in mid-Anadyr River. Triangle — Ornithological Camp.

The mid-Anadyr region is characterized by essential inter-year variation in weather conditions, phenology of vegetation and flooding regimes. For example, a late spring and high flood occured in 1989 and an early spring and small flood followed in 1990. A more detaled general habitat description of this area is given by L.A.Portenko (1939) and A.V.Kretchmar (1991).

Material and methods

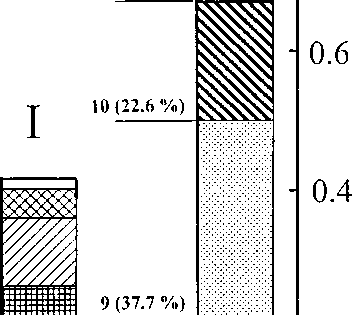

This study was performed during the summers 1989 and 1990 on the territory adjacent to the ornithological field camp on the Ubienka River (left arm of the Anadyr River, Fig. 1). Data on the spatial and habitat distribution of nesting pairs of buntings were collected on five contril plots (total area 116.4 ha) and included all biotopes that are characteristic for this area (Fig. 2). The basic types of vegetation associations in the landscape types were defined as follows.

For the flood-plain landscape: 1) Tall willows Salix undensis and alders (7-8 m) in the woods bordering rivers’ edges. The understratum in this area consists of tall grasses and horse tails. 2) Short, rare willows with easily flooded sedge pings. 3) Thickset bushes of short willows Salix krylovii (1.0-3.5 m) with sedge pings. 4) Dry areas with rare willows and alders that are mixed with thick blueberry bushes Vaccinium spp. 5) Occasional bushes of willow and a predominance of dry meadows. Currant and dogrose bushes also exist in this meadow along with grasses, irises Iris setosa and sedge pings. 6) Thick stands of dwarf birch with an understratum of grasses. 7) Dense thickets of shrub-pine mixed with alder and dogrose bushes on the small dry hills.

П km2

п 0.8

Fig.2. Ratio of biotopes in two landscapes.

Total square includes all control plots. Numbers of biotopes correspond to same in text. Persentages of total landscape in control plots are given in brackets.

II — floodplain; II — shrub-tundra

For upland shrub-tundra landscape: 8) Wetlands with peat-moss swamps and small thermokarst ponds. There are also sedge pings with cloudberries Rubus cha-maemorus, red bilberries, cotton grasses Eriophorum russeolum and low, rare bushes of shrub-pines at the small dry upland islands. 9) Occasional shrub-pines which are clustered in separate groves. The lichen-mounded dry tundra also contains dwarf birches Betula middendorfti, na-goonberries Rubus arcticus and Labrador tea Ledum spp. 10) Occasional shrub-pines with a big sedge pings and tiny lichen moss hills (approx. 3 m in diameter). Plant components of type 9 are also present. 11) Deep thickets of tall shrub-pines with lichen moss covering on the ground, Cala-magrostis langsdorffii and sedges Cares spp. pings and dwarf birches.

The number and location of nests were ascertained by means of regular walking routes during the entire breeding period of the buntings. For three breeding males, the sizes of individual territories were estimated by lengthy visual observations made from blinds placed close to the nests, from where the birds’ movements could be mapped. The observations on prenesting and nesting bunting behaviour were performed from blinds by means of point sampling- observations from fixed places with radius approx. 250 m.

Data on the time budgets of females and males during incubation period were obtained by observations from the blinds (the total time 30.5 hs) and by means of a time-lapse camera (Kretchmar 1978) for 59 hours (with intervals of 2.5 min). Descriptions of nests, eggs and juvenile plumage of newly hatched nestlings were performed by methods proposed by Miheev (1975), Kostin (1977) and Neifeldt (1970). Scaling photos of clutches and one-day nestlings were also made. Demonstrative songs of 8 males were recorded using tape-recorder “Reporter-6” (frequency range 20-20000 Hz) with paraboloid mirror. The recordings were analysed by the sonographic program of Biooptima Co. (St.-Petersbutg) with IBM PC 80286. Data on the nesting ecology of the rustic bunting, collected during 1977-1988 in the mid-Anadyr valley were originally published in the monograph “Birds of Northern Plains” (1991) and were used in the article thanks to kind agreement of A. V. Kretchmar.

Results and discussion

Phenology of breeding period

The average date of arrival to nest grounds in the mid-Anadyr region is similar to other northern parts of the rustic bunting range. Duration of migration period in the spesies comprise two mouths for total territory of breeging range (Tabi. 1). The limiting factor for its arrival date to the northern territories probably has to do with the snow melt phenology which determines the buntings’ access to food resources (grains of herbs) in early spring. Probably, this factor is not considerable in western breeding area where buntings’ arrival recorded for very early spring (Rymkevich 1979). Usually the first birds in this area appeared when the most part of their habitat was snow-free. Peaks of bunting arrival and of the number of singing birds were observed when the entire study area was free of snow. This time coincides with the second half of

May and the beginning of June (Tabi. 1).

The prenesting period for the rustic bunting lasts 8-12 days after arrival. The peak of the number of singing males was noted on the 29-30 of May in 1989 and 19-21 of May in 1990. The density of singing birds in the floodplain landscape was 94 males per 1 km2. During the next nine days their density decreased to 50 birds per 1 km2. This decrease had probably to do with a prenesting re-distribution as more birds arrived at the study area. While this situation was characteristic for floodplains, birds in the shrub-tundra were noted very seldom and episodically.

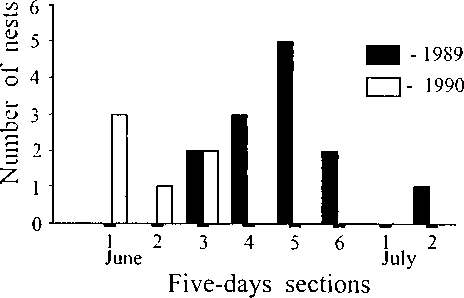

Usually laying period in the rustic bunting in the mid-Anadyr region is limited to the last three weeks in June (Kretchmar et al. 1991). The first clutch in 1989 was started on 13 June (Fig. 3). Total laying period stretched until the second week of July. However, a big flood in the second half of June had in undated most nests situated in the floodplain, and therefore, the small second peak of laying occured latter. It appears that the basic limitation for initiation of bunting breeding in floodplain area is a period of high spring floods that commonly ocur in the first half of June, while in shrub-tundra it is the snow melting phenology. Although most breeding pairs were forced out of the floodplain to the upland shrub-tundra, some birds built nests in the bushes.

Generally, the length of the nesting cycle for buntings in the mid-Anadyr region was on maximum 51 days which is shorter than nesting cycle of this species for eastern Finnish Lapland (Pulliainen, Saari 1989) and for southeastern coast of the Ladoga Lake (Rymkevich 1979). The duration of the nest ing cycle was determined by a combination of the variety of clutch initiation dates and the variety of time nestlings spent in the nest, the first one more then the second (Fig. 3). Fluctuation of flood waters during the first half of the breeding period is therefore an inportant factor in determination of the duration of the nesting cycle, but not influences to beginning.

Fig. 3. Time of clutch initiation in the nests of the rustic bunting in mid-Anadyr River.

Fledglings which have recently left their nests disperse on the grounds close to the willow bushes in the floodplain. For some days after fledge, parents support own young with food. I observed

Table 1. The chronology of spring migration for the rustic bunting in different parts of its breeding range

|

Region |

First birds’ appearing |

Range of migration time (including the arrival period) |

Time of snow melting on the most part of territory* |

Years |

Data reference |

|

South-Eastern Kamtchatka |

10-21 May, aver. 14 May |

20-29 May (data for 11 years) |

— |

1971-1985 |

Lobkov 1986 |

|

Mid-Anadyr River area |

28 May |

26-29 May |

26 May |

1931 |

Portenko 1939 |

|

— |

11-30 May |

16 May (aver.) |

1979-1988 |

Kretchmar et al. 1991 |

|

|

29 May |

29 May-7 June |

26 May |

1989 |

Present study |

|

|

14 May |

15-24 May |

12-14 May |

1990 |

Present study |

|

|

Kolyma Valley |

14 May |

— |

11-20 May |

1968 |

Kretchmar et al. 1978 |

|

— |

17-20 May |

11-30 May |

1973, 1974 |

Kretchmar et al. 1978 |

|

|

Kolyma Highlands |

23 May |

23-26 May |

End of May |

1964 |

Kistshinsky 1968 |

|

Southern Yakutia |

9 May |

First half of May |

9 May |

1956 |

Vorob’ev 1963 |

|

19 May |

First half of May |

16 May |

1958 |

Vorob’ev 1963 |

|

|

14 May |

First half of May |

13 May |

1959 |

Vorob’ev 1963 |

|

|

South coast of Ladoga Lake |

1-10 May |

— |

4 April |

1963 |

Rymkevich 1979 |

|

13 April |

3-6 May |

(in average) |

1975 |

Rymkevich 1979 |

|

|

Western Kola Peninsula |

6 May |

19 May (aver, for 16 years) |

— |

1977 |

Semyonov-Tyan-Shansky, Filyasov 1991 |

|

Eastern Finnish Lapland |

26 April (1983) |

14 May (aver, for 11 years) |

— |

1974-1985 |

Pulliainen, Saari 1989 |

* — Some data for snow melting have been borrowed from “Guide-book of USSR Climate”

(Since 1968; Numbers 3-32, Meteorological data from separate years. Part 3. Leningrad: Hydrometeoizdat).

a female with insects in its beak on 4 August. Groups of 6-14 birds undertook short feeding migrations to the osier-beds during August 6-14. The beginning of intensity autumn migrations was noted on 15 August through 28 August. By 4 September all rustic buntings left the study area.

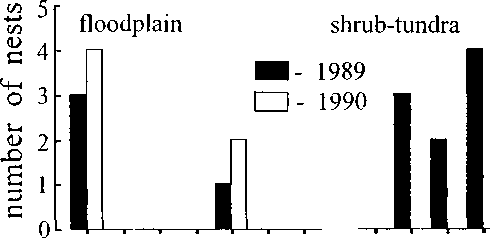

Use of the breeding area

Rustic bunting is a very common but not numerous nesting spesies in the mid-Anadyr River. At the control plots in shrub-tundra the density for its nesting population amounted to 23.8 birds per 1 km2 in 1989. There are not nesting birds in 1990. The density of population for the floodplain landscape amounted to 49.7 birds per 1 km2 for a year with long and high spring flood (1989, plot with 0.161 km2, this territory was most suitable for nesting) and 29.3 birds per 1 km2 for a year without pronounced flood (1990, 0.409 km2,

biotypical patterns

Fig. 4. Biotypical distribution of nesting rustic buntings for two basic landscapes. The numbers of biotypical patterns correspond to those listed in the methods section.

totally). The distribution of nesting buntings on the control plots for both landscape types is very uneven that is related to a degree of accessibility of nesting biotopes for water during a spring flood as well as during small floods after long downpours (Fig. 4). Thus, the biotopes 2, 3, and 4 were not inhabited by buntings because they fill the lowest places in the floodplain. Biotopes 6, 7, and 8 in shrub-tundra are the typically swampy places where small pounds are formed after a long rain that also did not creat conditions for successful nesting on the ground. However, the obvious nesting preference for the floodplain area is so strong that some pairs of buntings built up nests on willow bushes when a spring flood kept for a long time. Although the bushes along the river bed were occupied later than in the shrub-tundra, the density of breeding birds in the floodplain was higher. There is a large difference between Emberiza rustica and Emberiza pusilia, which lives in the same area. Generally, during long and high flood little buntings inhabit a shrub-tundra, where lives in nonflooding years too (Kretchmar 1993). This preference is not successful for breeding buntings for both years because 3 of 6 nests in 1990 were waterlog -gered in result of small not long flood in the end of June.

Individual territories

As remarked above, in 1990, 4-5 days after birds’ arrival at the study area the density of singing males was estimated as about 94 birds per 1 km2 for floodplain. However, the density of mating birds significantly decreased when all the nesting places was free of snow. The final structure of nesting population stabilized in the first ten-day period of June when a local migration was finished.

The daily visual shadowing to 3 males from nests under observation showed a minimal area for an individual male territory (where males displayed a high singing activity) amounted to 0.012 km2. Location of this plot coincided with a section of tall willow bushes along the river bed. The maximal area of an individual territory was observed in the shrub-tundra and amounted to more than 0.14 km2. The nest of this pair was located outside of the tall shrub-pine bushes on the slope of the low hill. There was not even a small single bush outside of the shrub-pine border so the male did not use this territory for demonstrative singing activity very often. However he settled a large section of willow bushes which adjoined the hill in the floodplain area rather well.

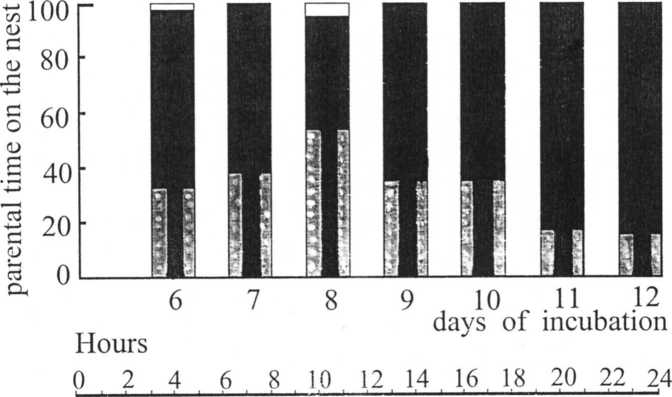

Parental care during incubation

Observations showed that during the second half of incubation period the male spent for incubation was 32.7±5.39% of day (mean ± S.E. for 7 days, Fig. 5). For the female it amounted to 67.1±5.43%. In last two days of parental care of female strength improved. During this time she moved eggs and ventilated the clutch more intensively. Male and female departures from the nest were not long (5-45 s) and occured in sunny weather.

26.06.1990

27.06.1990

28.06.1990

gy - male

- female

- departures

Fig. 5. A — The parental time spending for incubation during the 7 last days (total time of visual observation — 30.5 hs). В — 24 hours’ distribution of parental time on the nest during 6-8 days of incubation (time-lapse system data).

Nests, eggs, young

Typically, the largest number of explored nests were built on the ground in tiny, not deep holes under the small bushes and (or) under protection of mounds. Some nests were hidden very well by sedges or grasses, a type of plant cover is peculiar to places in floodplain for biotopes 1 and 2. For shrub-tundra Labrador tea, little birches and shrub-pine are more typical plants for nesting camouflage. Among 8 nests situated on the ground, only 2 had more than one entrance hole.

Three nests were built in tall bushes (0.93-1.8 m from the ground). Two nests were situated on the bushes’ forks, one was rotting in a hollow of a willow. Similar nest sites for the rustic bunting are known for other parts of the range (Lobkov 1986; Pulliainen, Saari 1989; Semyenov-Tyan-Shansky, Gilyazov 1991). These nests were noted only in waterlogged areas for years with long and high flooding in 1986 (Kretchmar et al. 1991) and 1989.

Nests of the rustic bunting have compact walls (in comparison with nest of the little bunting) and are woven of stems of small dry grasses. The bottom of nest are lined with a thin layer of reindeer hairs. The total sizes were fluctuated greatly, depending on nest sites and data of egg laying. Thus, nests built late in the season had thinner walls. External nest sizes reached 75-110 mm (including variation of asymmetrical nests), diameter of nest cap 50-74, in average 60 mm, the depth of cap 37-55, in average 40 mm (л = 15).

The colour patterns density in the rustic bunting eggs varied over a wide range. These patterns changed from very dense dark brown patterns on the whole egg shell to small brushed brown spot on the infundibular egg pole. The pigmented parts occupied from 15 to 78% of total shell surface. More typical eggs are marked with dark brown, indistrict patterns with tiny black specks, dots, commas and narrow lines. There is such patterns covered about 50% (л = 52). T.A.Rymkevich (1979) noted that for the western part of the rustic bunting breeding range the small black markings are not common on the egg-shell surface. In the mid-Anadyr River region they are very usual for the most eggs.

Egg sizes (и = 119), mm: 17.7-21.9x13.7-16.2, in average 19.7±0.09xl5.0± 0.05 (± S.E.\

Newly hatched nestlings (л = 12) showed well developed juvenile down on the supercilliary line, nape, shoulders, back, elbows, thighs and tarsus. Down has a well-developed rami and parii and lenght about 13 mm. Moreover, all fuzzlings had a two simmetric down sectors (length 5 mm) on the belly. Presence neoptile on the belly is good sign that differ fuzzlings of the rustic bunting from the little bunting which has not neoptile here (Kretchmar 1993). The neoptile on the primary sites and on the tail is short (2-5 mm) and setaseous. Body colour is pale-rose. Down is grey; bill — grey-white with white mouth corners. A similar description was obtained for the rustic bunting from western part of range (Rymkevich 1979). The facultative presence of neoptile on the belly was observed for the Emberiza aureola (Neifieldt 1970), indicating their relatively close systematic relationship.

Clutch size

In 1932 L.A.Portenko found two nests of rustic bunting with 5 and 6 eggs (Portenko 1939). A.V.Kretchmar in 1986 noted that clutch size varied from 3 to 5 eggs (3.9±0.21, n = 9 — Kretchmsr et al. 1991). Clutch sizes for 1989 were similar to those observed in 1986, while for 1990 clutches it had more considerable

Table 2. Clutch size of rustic buntings in 1989-1990 (probably including the repeated clutches)

|

Year _ |

Number of eggs |

||||

|

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Mean ± S.D. |

|

|

1989 |

2 |

6 |

5 |

0 |

4.2±0.73 |

|

1990 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

5.2±0.75 |

|

Total |

2 |

7 |

8 |

2 |

4.5±0.84 |

size on average (Tabi. 2). Thus, there is relatively low reproductive success evidencing for harsh seasons. I am not analysing detail factors and ways for relatively clutch decreasing but undoubtedly this situation typical for studied area where 7 of 16 years were distinguished by harsh environments.

Singing activity

Rustic buntings perform a song with well-formed syllables and phrases. Instead they perform an irregular modulated chirruping, similar to the songs of warblers (Portenko 1939). This song has a duration of 1.21-2.23 s and frequency range of 2.0-8.3 kHz (Fig. 5). All notes are represented as one harmonic with a fast change in modulation.

Such a style of singing has created an ample variety in the repertoire of every male rusting bunting. Only the ending flourish of the song has a similar frequency pattern for every male. A nesting male is also able to produce a short, quiet “subsong” if a strange male approaches the nest.

In general, rustic bunting songs are similar to those of the Emberiza elegans (description see: Il’insky 1980) in the Southern Primorie (Russian Far East). This species is known to have a boreal distribution.

Finally, present studies show that the rustic bunting in the middle reaches of the Anadyr River as southern subarctic species has a tendency to inhabit floodplain area with lowland woody vegetation. In spite of the presence of vast, unsaturated surfaces, buntings prefer to inhabit the floodplain. This preference leads to decreasing reproductive success in seasons with harsh conditions. The harsh weather conditions during beginning of incubation are (including the melting phenology and flooding regime) curtail the nesting cycle for 51 days that shorter than in orther parts of its range.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank I.V.Il’insky and VAFedorov for their detailed comments during preparation of manuscript drafts. A.V.Kretchmar offered some notes in that permitted to extend understanding of buntings’ breeding biology in this area. Yu.B.Pukinsky kindly gave me access to Kay Sona-Graph machine for making sonograms of some recordings. Aso I thank AG.Zinov’ev for help with identification of some plants species. I am very indebted to the assistance with correction of manuscript translation to K.Rock, M.Williams and I.Kutzkova.