The Study of Economic Conditions and Financial Stability in the Safavid Era, Iran Based on the Analysis of Silver Coins from this Era by the XRF Method

Автор: Nouri S., Neyestani J., Karimian H.

Журнал: Краткие сообщения Института археологии @ksia-iaran

Рубрика: Средневековье и новое время

Статья в выпуске: 280, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The Safavids ruled over Iran perpetually from 1501–1502 to 1722–1723. They were one of the most influential governments in politics and economy after the rise of Islam. Until now, this period’s economic conditions have been studied and investigated based on historical resources. However, this research has provided an opportunity to assess and evaluate the stability of this period’s financial and monetary power using the laboratory results of examining the existing coins. In this research, 30 silver coins kept in the Money Museum in Tehran were selected and analysed for elemental composition using X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) method in the Geological Laboratory of Tarbiat Modares University. The collection includes coins from the reign of Shah Ismail I (1502–1524 AD) until Shah Sultan Hossein (1694–1722 AD). These coins are from various mints in Iran’s current political borders and Greater Iran’s regions. The study of Safavid silver coins reveals the high purity of the silver metal. It also demonstrates that despite the unpredictable political history of the Safavid Shahs during this period, they consistently maintained the economic authority necessary and the quality and purity of the coins. Although there were fluctuations in the weight of the coins, the value of the silver coins remained relatively stable compared to other eras.

Safavid era, silver coins, elemental analysis, XRF method

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143185166

IDR: 143185166 | DOI: 10.25681/IARAS.0130-2620.280.430-442

Текст научной статьи The Study of Economic Conditions and Financial Stability in the Safavid Era, Iran Based on the Analysis of Silver Coins from this Era by the XRF Method

Since the invention of the coin, it has been a symbol of the political and economic power of the governments, in addition to the means of exchange. One of any government’s most essential and urgent priorities is minting coins, so the political economy is closely linked with money and coins. The quality of the coin also symbolizes the economic status of the government and the country, and its rarity and abundance always affect the government’s financial power and economic status of the country.

The Safavid period was no exception to this principle. During the Safavid period, when Iran was the centre of global developments, the issue of money and related issues became more complex. Iran’s currency faced competition with other currencies from the Indian subcontinent and Japan in the East and Europe in the West. This heightened the currency’s significance in Iranian economy and even politics making related issues a concern for the rulers ( Matthee et al. , 2016. P. 15). Therefore, in the early 16 th century AD, the Safavid dynasty entered the field of domestic and international economy and trade with a different power than the previous dynasties. consequently, the economy of this period became more systematic and coherent.

The Safavid monetary and financial system is one of the most fundamental parts of the economic history of this period. The study of its coins reveals the importance of this issue more than ever. Like other governments, the Safavids, had control over coin production, ensuring the weight and quality of the coins. The government authorized different individuals to establish mints to achieve its commercial and economic goals. However, the performance supervision was still under the government’s monopoly; especially in minting silver coins. Additionally, the central government oversaw these coins’ minting process (Ibid. P. 48).

The Safavid monetary system was based on gold, silver, and copper. Silver dirhams included the mass of coins minted in this period, and silver coin was the only real currency. Some sources suggest that coins were usually minted based on a specific weight standard (Ibid.). However, did the Safavid silver coins follow consistent principles regarding fineness and purity? Or were these characteristics subject to change due to political, economic, or financial influences from different mints? If so, how acceptable were these changes? How stable was the quality of the coins of this period? Furthermore, did the value and weight of silver coins fluctuate as a result of various political and economic conditions?

During the reign of Shah Ismail, the founder of the Safavid dynasty, there were many political difficulties, including successive wars, which also affected economic issues. In the reign of Shah Abbas (1587/1629 AD), his domain reached relative stability in terms of economy and trade and had many activities. The successors of Shah Abbas, such as Shah Safi (1629–1642 AD), survived the economic conditions of their period slightly better. However, during the reign of Shah Soleiman (1666– 1694 AD), the lack of money increased. It seems that throughout this turbulent reign, there was an effort to preserve the quality of silver coins, primarily used in trade. This issue can be seen in the appearance of the coins and sometimes their weight, but was the purity maintained? Responding to these questions, some Safavid silver coins from different shahs and mints were selected, examined and studied.

Historical Background

The history of using laboratory methods in studying Iranian coins is less than a century. For the first time in 1950, the American chemist Caley took advantage of laboratory studies in the study of Parthian coins of Ard II (4–8 AD) (Caley, 1950). In his subsequent research he compared them with their contemporary Roman coins (Caley, 1955). Iranian researchers gradually started to use non-destructive laboratory methods to study archaeological artifacts (Lamehi Rashti, 2003). Gradually, laboratory methods, especially PIXE and XRF, became common in analyzing and investigating archaeological data. The scope of interdisciplinary cooperation between archaeological studies and other sciences became wider. Many tests were done on coins, especially by the PIXE method; among them is an article entitled «Statistical study of Achaemenid, Parthian, and Sassanid silver coins using elemental Analysis through PIXE method» which is one of the first examples of testing on coins using laboratory method by Oliaiy and colleagues (Oliaiy et al., 1999). Then, more case studies were conducted on the coins of different dynasties and kings (Haji Tabar, 2015; Sarbishe et al., 2022; Kaziri et al., 2019; Khademi Nadooshan et al., 2015; Kianzadegan et al., 2019; Ko-hestani Andarzi et al., 2019; 2020; Masjedi Khak, 2012; Masjedi et al., 2013; Sabzali et al., 2011; 2022; Sodaei, 2016; Sodaei, Kashani, 2013; Yousefi et al., 2021]. However, almost all the studies in Iran have been conducted using the PIXE method, and its availability is one of the reasons for choosing this method. In a few cases, the XRF method has been used (Sabzali et al., 2010). It should be noted that the mentioned studies all include different periods such as Sassanid, Parthian, Seljuk, and others. So far, no elemental Analysis has been conducted on the coins from the Safavid period, except for the article of Rudi Matthee, who also only focused on the Hoveyzeh mint using the PIXE method and analyzed the elements of coins and economic problems of the late Safavid era (Matthee, 2001). Therefore, it can be said that the present research focusing on Minting conditions in the Safavid silver coins based on elemental Analysis of samples by the XRF method is new research and a beginning for further study of this period and this subject.

Research method

In the laboratory where the XRF Analysis was performed (Taribiat Modares University), the device model is Philips PW 2404, and the device calibrationis set to SEMIQ from B.V. standards samples of Powerlitical Company, and the detection values are from 50 to 100 % Ppm with a range of 44 elements, including Cs, Ga, Rb, Cl, Na, Ba, F, S. Mg, Cr, U, Sr, Pd, Pt, Ge, Mn, Mo, Br, La, K, Pr, Ta, Zr, Al, Fe, P, Si, Sm, Zn, Ca, In, Nb, Nd, Ti, W, Bi, Ce, Co, Hf, Th, Y, Hg, Ni, V, Pb, Sn, Ag, As, Se, Te, Sb, Cd, Cu, I, and Tl have been analyzed, if they are present in the samples.

Sample Preparation

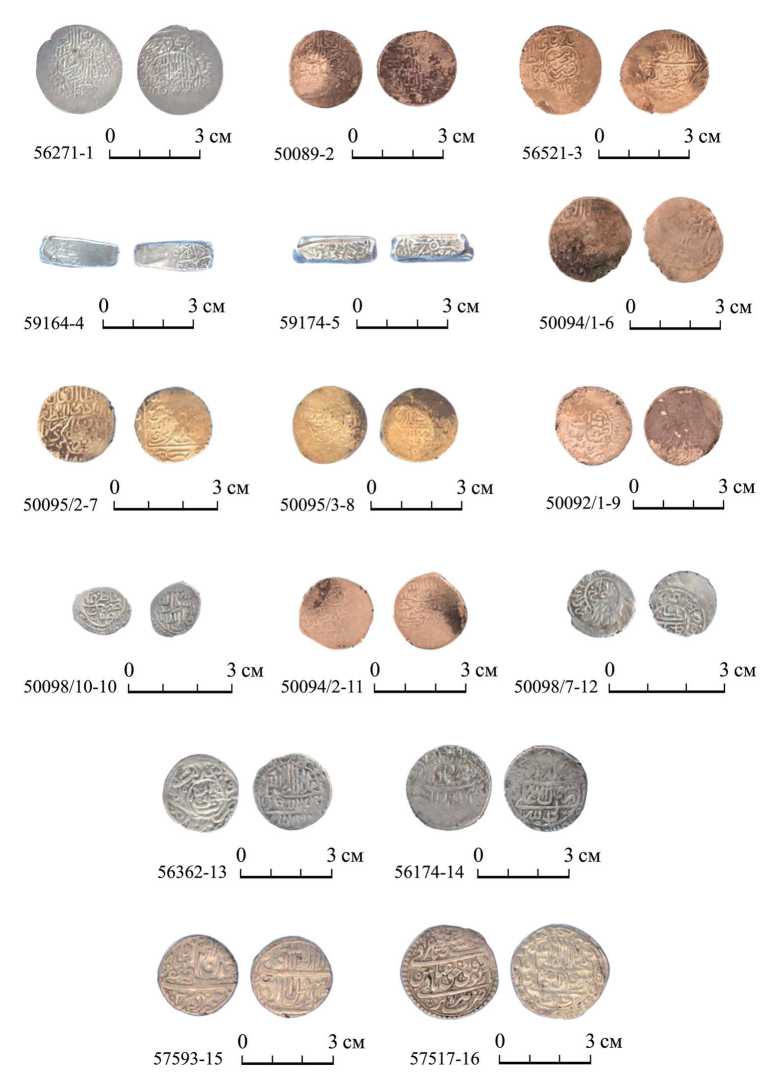

In this research, 30 coins were selected from the treasury of the Iranian Money Museum, which belonged to different Safavid shahs (Ismail, Abbas, Safi I, Tahmasb I (1524–1576 AD), Abbas II (1642–1666 AD), Soleiman I and Soltan Hossein) and were all made of silver (Fig. 1) (except for number 30 which contrary to the museums identification card and the silver appearance was not made of silver). Selecting the samples, an effort was made to ensure that the coins belonged to different mints so that the amount of changes in the elements and the quality of the samples could be compared more accurately. The coins were completely clean and free of environmental contamination; therefore, they were cleaned only with water and alcohol. The selected samples originated from various locations in Iran, including Mashhad, Isfahan, Kashan, Tabriz, Qazvin, Sari, Semnan, Estrabad, Haveyizeh, Siraf, as well as

Fig. 1. Examples of studied coins areas outside the current borders of Iranincluding Herat, Yerevan, Ganja, Nakhjovan and Shamakhi. when using the XRF method, samples are occasionally taken from artifacts due to reasons such as the large size of the object. Only one spot was tested due to cost-saving reasons. However, no sampling is required for examining coins. Therefore, the provided samples are complete and were tested without any alterations.

Result and Discussion

The weight of the coins in these 30 samples varies significantly, while the purity of the silver is maintained (tabl. 1). For instance, during the reign of Shah Tah-masb I, some silver coins were minted with a lower weight than in previous years, so that the approximate weight of about 4–5 grams has decreased to 1 gram. The results of some tested samples indicate that the purity of one-gram coins has been preserved and has not changed, and it has been tried to preserve the silver of the coins up to 90 %, even though in many historical periods of Iran, many impurities have been seen in the minting of silver coins. Unlike the Parthian period, during the Safavid era, the purity and quality of the coins have been consistently maintained at a high level across all analyzed samples, despite the extensive geographical reach and the number of mints in that era.

Table 1. Characteristics of analyzed coins and their mints

|

Number |

Accession number |

King |

Name of coins (after: Album, 2011) |

Weight (gram) |

Mint |

|

1 |

M 56271 |

Shah Ismail I |

Doshahi |

3/9 |

Herat |

|

2 |

M 50089 |

Shah Ismail I |

Doshahi |

5/1 |

Mashhad |

|

3 |

M 56521 |

Shah Ismail I |

Doshahi |

5/3 |

Tabriz |

|

4 |

M 59164 |

Shah Ismail I |

Doshahi |

5/1 |

Larin |

|

5 |

M 59174 |

Shah Ismail I |

Doshahi |

5/1 |

Larin |

|

6 |

M 50094/1 |

Shah Tahmasb I |

Doshahi |

4/7 |

Sari |

|

7 |

M 50095/2 |

Shah Tahmasb I |

Doshahi |

4/6 |

Semnan |

|

8 |

M 50095/3 |

Shah Tahmasb I |

Doshahi |

4/7 |

Estar Abad |

Table 1 continued

|

Number |

Accession number |

King |

Name of coins (after: Album, 2011) |

Weight (gram) |

Mint |

|

9 |

M 50092/1 |

Shah Tahmasb I |

Doshahi |

5/1 |

Tabriz |

|

10 |

M 50098/10 |

Shah Tahmasb I |

Shahi |

1/1 |

Esfahan |

|

11 |

M 50094/2 |

Shah Tahmasb I |

Doshahi |

5/2 |

Qazvin |

|

12 |

M 50098/7 |

Shah Tahmasb I |

Shahi |

1/2 |

Shamakhi |

|

13 |

M 56362 |

Shah Abas I |

Doshahi |

3/8 |

Hoveizeh |

|

14 |

M 56174 |

Shah Abas I |

Abbasi (charshahi) |

7/7 |

Yerevan |

|

15 |

M 57593 |

Shah Safi I |

Abbasi |

7/4 |

Tabriz |

|

16 |

M 57517 |

Shah Abas II |

Abbasi |

7/2 |

Tabriz |

|

17 |

M 57488 |

Shah Abas II |

Abbasi |

7/3 |

Tabriz |

|

18 |

M 57476 |

Shah Abas II |

Abbasi |

7/2 |

Tabriz |

|

19 |

M 57530 |

Shah Abas II |

Doshahi |

5/4 |

Tabriz |

|

20 |

M 50107 |

Shah Soleiman I |

Abbasi |

7/3 |

Yerevan |

|

21 |

M 50106 |

Shah Soleiman I |

Abbasi |

6/7 |

Nakhchivan |

|

22 |

M 76559 |

Shah Soleiman I |

Abbasi |

7/3 |

Siraf |

|

23 |

50105/2 |

Shah Soleiman I |

Abbasi |

7/2 |

Nakhchivan |

|

24 |

57475 |

Shah Soleiman I |

Abbasi |

7/3 |

Ganja |

|

25 |

50109/2 |

Shah Soltan Hosein I |

Doshahi |

5/4 |

Mashhad |

|

26 |

*56181 |

Shah Soltan Hosein I |

– |

6/3 |

Esfahan |

|

27 |

M 01801 |

Shah Soltan Hosein I |

Shahi |

2/6 |

Tabriz |

|

28 |

M 50111 |

Shah Soltan Hosein I |

Doshahi |

5/3 |

Qazvin |

|

29 |

M 49710 |

Shah Soltan Hosein I |

Doshahi |

5/4 |

Qazvin |

|

30 |

M 57493 |

Shah Soltan Hosein I |

Doshahi |

5/3 |

Tabriz |

Note: * – This coin was classified as silver based on the museum’s certificate and at the museum’s insistence, just based on its appearance. However, laboratory tests determined that it is not silver but bronze. Consequently, it remained on the list of coins analyzed for verification purposes.

In the analysis of these samples, various elements, including silver, copper, lead, gold, sodium, magnesium, aluminium, silicon, phosphorus, sulphur, chlorine, calcium, iron, mercury, potassium, zinc, tin, and even bismuth, niobium, rubidium, Bromine, and titanium were identified. The percentage of each was determined separately (tabl. 2, see in the end of the paper). The standard limit of silver metal used in this material is typically 90 %, which is also the case in the Safavid period. The test results show that the highest amount of silver used in the samples of coins is 97,7 % and the lowest is 86,3 %. In contrast, we are facing a much lower percentage in other governments.

In the sample table, the lowest amount of silver belongs to coin number 56181, with 0,089 %. Despite its silvery colour, it was determined to be bronze during the test. Elemental analysis results show that this coin is made of bronze with silver plating, a method used for coin forgery in which the forger gives the appearance of a silver coin by coating a low-value metal with silver. Since this coin is a type of knuckle coin of Shah Sultan Hossein’s reign, and on the other hand, knuckle coins have only been reported in silver so far, probably this coin is a contemporary forgery sample with a very high mintage similar to the original samples or at the same time, was minted with the appearance of silver but made of bronze. Lowering the purity of a coin by adding a lower metal is one of the forgery methods, but these types of coins were infrequent in their time and only a few examples have been reported so far ( Nadushan, Moosavi Jashni , 2006. P. 24).

During the Safavid period, another method to control the mintage of coins and increase their number involved reducing the weight of silver used in the coins. According to the samples studied, it can be said that, this method was also used during the reign of different shahs. This was permitted by the government, allowing mints to lower the weight of silver coins while maintaining the percentage of silver. Since copper was added to increase the hardness and resistance of silver, the silver coin could contain 10 % of copper. Additionally, when silver is melted. It naturally retains a small amount of copper ( Rodriguez , 2004) usually less than 1 %. If the amount of added copper (Cu) is higher than 1 %, it suggests that the current coin is probably made by melting coins of the previous period or copper metal has been added to it intentionally. This was likely a response to the political-economic developments during the reign and the decisions made by the Safavid shahs to control the economic conditions.

The mines from which coins’ metals are extracted have specific chemical compositions and a constant amount of rare elements. For example, silver mines contain gold as a rare element, while gold mines contain platinum. By comparing the rare elements it can be determined that which mines were used. Regarding the used mines, according to the few and heterogeneous results available, it can only be stated that the samples were taken from mines that contain gold as a rare element.

Conclusions

According to historical sources from the Safavid period, the Mu’ayyir al-Mamalik was a court official appointed by the Shah, responsible for overseeing state mints. He exercised strict supervision over the minting of coins. The Mu’ayyir held the highest authority in the minting workshops and generally oversaw financial auditing matters as well. At the final stage of the minting process, before the newly minted coins entered the country’s financial circulation, he conducted a thorough inspection of the coin’s standards – including the names, titles, and image of the monarch, as well as the accuracy of the weight, metal content, and fineness – to prevent the spread of counterfeit or defective coins in society.

As previously mentioned, during the Safavid era, different cities had their own mints, and sometimes a single city housed more than one mint. The right to mint coins was granted by the Shah and could be leased to other individuals under the supervision of the central mint. However, these individuals were required to comply with standards set by the government.

The issue of strict supervision in Safavid mints can be evaluated through the study of coins minted in the various and numerous political centers of the time. For this reason, in the present article, careful attention has been given to the minting location of the coins selected. Therefore, efforts were made to choose samples from different mints within the Safavid domain to allow for better comparison in terms of quality, elements, and the precise control of their weights.

Analysis of 30 coins from the Safavid dynasty indicates that the silver coins minted during the different governments remained consistent despite anyeconomic and political changes. According to the concentration of the silver element in the tested samples, the weight of the silver coins of the Safavid era varied due to economic problems caused by political issues, yet the purity of the coins always followed a general and fixed discipline. By conducting the present research, at least we can speak more confidently about the Safavid silver coins. The standard amount of silver metal used in this period is 90 %. The elemental analysis confirmed that the highest amount of silver used in the samples was 97,7 % in the reign of Shah Ismail I and Sultan Hossein, while the lowest amount was 86,3 % during the reign of Shah Suleiman I, which is a very acceptable amount in mintage of silver coins.

In addition, the table of combined elements indicates the difference in the microelements of the mentioned samples, which could be the result of using various mines or sources in producing coins. However, the main elements are standard, indicating high quality and precision in producing silver coins during this period. For instance, considering the amount of lead element in the samples, which in most cases is less than 1 % and at most around 2 %, suggests that this amount of lead naturally coexists with silver and that silver is extracted in a correct way. The copper content in the coins is reported to be no more than 4 %, which is normal and indicates that no additional elements, such as copper or lead, have been added to maintain the purity of the primary silver.

The comparison of the percentage of gold in the studied silver coins indicates that the primary silver extracted from mines naturally contains gold as a rare element. It is important to note that the continuous melting of metals in different periods to prepare new coins, causes changes in the value of coins. Also, the lack of information about ancient mines has made it very difficult to identify the mines and the place of extraction of the studied metals based on rare elements.

The analysis results show that the samples’ primary metal was taken from Galena ore (lead sulphide mineral) – PbS. In addition, all the samples have a significant percentage of gold, which can be helpful in limiting the used mines. Based on this, the mines that are used naturally contain a percentage of gold.

According to historical evidence, the Safavid coins were minted in the mints of other parts of the government territory in addition to the royal mint. This research assumed that the mints that were directly under the supervision of the king or his representative (the so-called capital mints or royal mints) minted the best quality coins.

In addition, sometimes, the quality of coins changed due to economic problems and political conditions such as war and famine. However, the elemental analysis of the samples shows that in addition to the central mints, other mints in the government territory have also followed the necessary grades and standards well.

The research results show that even the samples of coins minted far from the capital, such as the Tbilisi and Nakhchivan mints, were required to comply with all the standards approved by the royal mint. Also, due to the existence of many tensions in the Safavid era from the establishment until their fall, in most cases, silver coins were minted at the highest level of purity and with the least impurities, such as lead, copper, or other low-value elements. In other words, the ratio of changes of copper to silver, lead to silver, and also gold to silver is tiny. This research indicates that the Safavid governments have always tried to keep the value of their silver coins at the highest standard, away from any political and economic influences.

Based on the elemental analysis results presented in this article, it can be concluded that these studies have shown that Safavid-era silver coins typically possess a silver purity exceeding 90 %, aligning with historical standards. This high purity likely aimed to maintain economic value and public trust. Additionally, some samples exhibited varying elemental compositions, which may indicate the use of different silver sources or changes in the production process.