The urgency to imagine a new paradigm. The labour market between global trends and peculiar Italian features after the COVID-19 pandemic

Автор: Fontana Renato, Calo Ernesto Dario

Журнал: Уровень жизни населения регионов России @vcugjournal

Рубрика: Экономические исследования

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.18, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This paper aims to examine the peculiar characteristics of the Italian working situation after the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, starting from the forecasts on the impact of the Digital Transformation (DT) on the global labour market, the authors try to combine the macro and micro-social risks related to this process with those arising from the pandemic scenario, finding a common thread that seems to return the sign of these times. Observing the Italian context, some reflections are provided to rethink the balances of the world of work, in particular through the use of the digital technologies, the plural forms of remote working (RT) and the prevention of the youth unemployment and great resignation phenomena.

Labour market changes, digital transformation, remote working, great resignation, covid-19 consequences, italian case study

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143179144

IDR: 143179144 | DOI: 10.19181/lsprr.2022.18.3.4

Текст научной статьи The urgency to imagine a new paradigm. The labour market between global trends and peculiar Italian features after the COVID-19 pandemic

The change linked to Digital Transformation (DT) – already understood as the transversal process of redefining the communicative and organizational areas of the company through the use of Information & Communication Technologies (ICTs) – is included, among other cases, in the group of requests to cope with in order to pursue the desires of a new economic and production structure that can effectively benefit from the potential offered by digital technologies.

In today's Network Society (Castells, 2014) and more recent Platform Society (van Dijck, Poell and de Waal 2019), a widely understood renewed idea of productivity seems to prevail over others, namely the one founded and supported by a longterm rationalization that leans towards the “infinite possibilities” offered by the digital (Bonivento, Gentili and Paoli, 2011, Lucchese, Nascia and Pianta, 2016).

This common vision also causes a concrete impact simultaneously on the time and space of action of individuals, as well as on their increasingly mediated interpersonal relationships, helping to make the distinction between work and leisure, as well as between public and private, progressively more opaque., thus returning a complex polyvalence of effects – positive and negative – that such a conception of productivity inevitably brings with it. It is here that the human aspect is revealed in its centrality, demanding attention to the social dimension of this change, beyond the purely technological aspects related to it.

To achieve a synthesis between the two evoked dimensions (the technological and the human one) we could speak of a technical vision of change, but only when we consider the etymological derivation of this term, which refers to the typical ability of man to govern the object ( τέχνη = “art”, in the sense of “expertise”, “know how”, “knowing how to do/operate”). This is even more evident in the workplace, within which man expresses himself and at the same time draws meaning for the construction of his own identity (be it purely creative or instead inserted in a more binding man-machine relationship). Therefore, even the most cynical and measured of the interpretations linked to DT – as happens for some conceptions of Industry 4.0 that we could define as positivist – could not fail to consider the human being as a protagonist, an acting actor but also an acted one (Brynjolfsson and McAfee 2014, Cirillo and Guarascio 2015, Mazzucato et al. 2015, Urbinati et al. 2020).

Itgoes withoutsayingthateffectivelyadministering such a transformation1 requires duly extensive reflection. A reflection that takes into account the multiple micro and macro-social implications, which from time to time are revealed in spite of the political and economic-productive aspects underlying what has been defined by many as the “Fourth Industrial Revolution” (Rullani and Rullani 2018, Salento 2018).

With regard to the macro-social implications, it is appropriate to recognize how the flexibility of organizations, as a consequent response to a broader paradigm of production flexibility, is showing the traits of a progressive precarization and “recommodification” of work (Gallino 2007).

In an attempt to interpret some social phenomena related to the world of work, in the following pages we intend to reflect on some aspects, both quantitative and qualitative. Therefore, in the next section, we will describe more general trends related to the global economy and the global labour market. Subsequently, we will switch progressively from the global condition to the Italian specific context, which, in some ways, absorbs the impulses arising from outside, while, from other perspectives, it is configured as a particular field of application of new ways of understanding work and its organizational processes. These reflections will be supported by focusing on two case studies concerning the so-called “remote working” and “great resignation” phenomena (and their manifestation in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic). Finally, some provisional conclusions will be drawn.

Implications of the Digital Transformation between Economics and the Labour Market

With the advent of unprecedented organizational forms, various phases of the production and management process pour into the Web, and the legislative delay in the administration of these “virtual places” favors the spread of ambiguous work performances, with the consequent need for a new protective system that defines the areas of legality within which to regulate the meeting between labour demand and supply. The new and stringent conditions of global competitiveness – often suffered by the entrepreneurial system, at times managed with difficulty, at other times brazenly embraced for pure gain – make it increasingly difficult to maintain a balance between the economic-productive fabric and the workforce that animates it. In this elusive dynamic of control, which suggests an exacerbation of radicalization phenomena, the new digital technologies play an absolutely central role.

The data of some estimates on the future of work in the coming years (World Economic Forum 2018, Fondazione Ergo 2019), which hoped for a global increase of 58 million new job positions2, have more recently been denied and reviewed in consideration of the further critical moment constituted by the COVID-19 pandemic. This historic event, in fact, not only caused a “physiological” wave of unemployment – in addition of course to the enormous damage in terms of health –, but also “Inequality is likely to be exacerbated by the dual impact of technology and the pandemic recession. […] The COVID-19 pandemic appears to be deepening existing inequalities across labor markets, to have reversed the gain in employment made since the Global Financial Crisis in 2007-2008” (World Economic Forum 2020, p. 5).

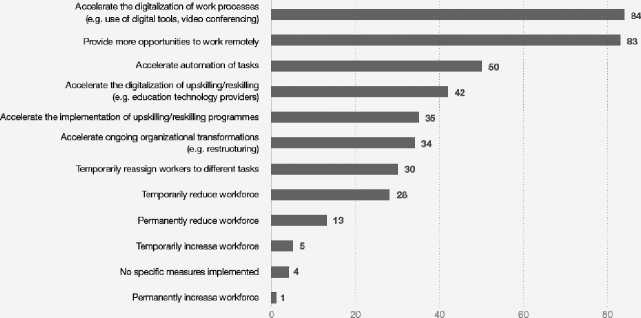

The current forecasts to 2025, due to a substantial update, suggest a loss of 85 million jobs, compared to 97 million new professions declined on the basis of equally new corporate organizational processes. This is obviously a balance (+12 million) which, although positive, is far from the one forecast just a year earlier. Furthermore, according to the same source, beyond the measures taken in response to the pandemic emergency (Figu re 1), 55% of companies still seem to

Share of employers surveyed (%)

Figure 1. Planned business adaptation in response to COVID-19

Рисунок 1. Запланированная адаптация бизнеса в ответ на COVID-19

Source: World Economic Forum (2020).

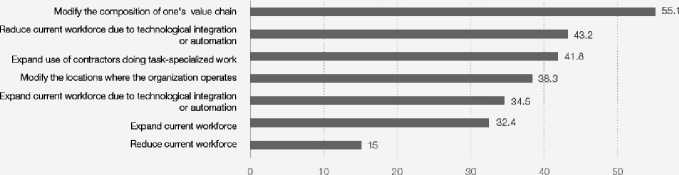

be willing to act actively for a further restructuring of their value chain by 2025, with 43% of them planning to take up employment due to the integration of new technologies into production processes3 (Figures 2-3).

These same data have been roughly confirmed by other scholars, leaving no room for doubts about the prevailing impact that technology causes on the labour market, especially if support and welfare policies are not properly advanced (Marzano 2016, Falcone et al. 2018, Acemoglu and Restrepo 2020, Astrologo, Surbone and Terna 2019, Daugherty and Wilson 2019, Posada 2020, Steinhoff 2021).

Share of company surveyed (%)

Figure 2. Companies' expected changes to the workforce by 2025

Рисунок 2. Ожидаемые изменения в рабочей силе компаний к 2025 г.

Source: World Economic Forum (2020).

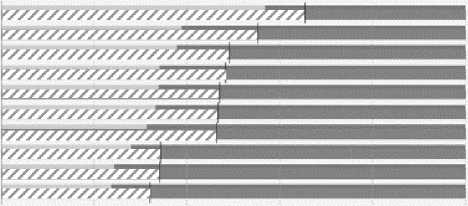

Identifying and evaluating job relevant information

AJUmI®

Perlorrnng phyoca# and manual work actMtiee G-ii ■ i cricalng nd ri l стacting fiAa^ning and decide-mgfchg Cocrdrarthg. developing, managhg and adwsrg

o 20 40 eo ao 1®

Share ol taek bourn (%}

MncHnc2C2D — Human2020 <■■ Mad*® 202 5 ■ Human 2025 — Human- niadwie frontier 202'5

Figure 3. Share of tasks performed by humans VS machines, 2020 and 2025 (expected)

Рисунок 3. Доля задач, выполняемых людьми по сравнению с машинами, 2020 и 2025 гг. (ожидаемая)

Source: World Economic Forum (2020).

Beyond the quantitative aspects.A matter of quality

If the quantitative problematic aspects linked to the world of work reflect those difficulties that emerged due to the acceleration of the DT process (for example automation, advanced digitisation and the succession of industry 3.0 and 4.0 paradigms) and the COVID-19 pandemic, some qualitative aspects are more attributable to long-term social changes that have occurred in a broader conception of work. Recent studies have acknowledged the major impact of Industry 4.0 (I4.0) not only on companies and business sectors but also on the environment and society at large (Jabbour et al. 2018, Müller and Voigt 2018, Bai et al. 2020, Beier et al. 2020). For example, Ghobakhloo (2020) provided an interpretative model of how I4.0-related techno-industrial revolutions can contribute to the achievement of economic, social, and environmental sustainability. Thus, the function of work in society acquires a broader meaning, which is related not only to the mere employability (being employed or unemployed), but also to other deeper aspects that affect the identities of the people themselves, the way in which societies organize themselves, existing disparities, new disparities, and so on.

The advent of the Knowledge Society (Drucker 1969) meant that the variables of employability4 and income are significantly associated with a clear distinction between the working class – the typically twentieth-century “blue collars” – and knowledge workers, with these the latter who have enhanced their intellectual capital both in terms of productivity and in terms of wages.

In other words, to quote Taylor (1911), the resistance of the “ox-man” wedged between the gears of the assembly line was equal only to that of the entire industrial manufacturing sector, which in the second half of the last century had already experienced a first process of strong deindustrialization and automation following the introduction of the first electronic and IT components.

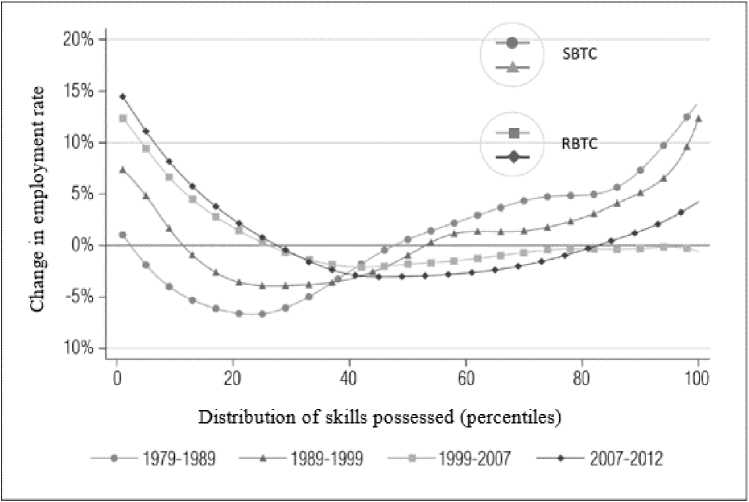

Yet this configuration has undergone partial changes since the 2000s (Figure 4), when the growing investment in ICT introduced a further discriminating element (Frey and Osborne 2013, 2015, Ford 2017, Frey 2020), shifting the focus from of skills possessed (skill-biased technological change - SBTC) to the degree of “routinization” of the activities (routine-biased technological change – RBTC) (Autor 2013, Vivarelli 2013, Autor 2015, ILO 2016, Eurofound 2017).

In this regard, those that are outlined as global trends are also valid in the specific Italian context. The European Center for the Development of Vocational Training (CEDEFOP 2018) notes that in Italy the percentage of jobs characterized by routine and intermediate tasks is higher than the European average, which is why the same Institute associates a higher substitution risk, which at this point also affects a significant part of knowledge workers (Unioncamere – ANPAL 2018, 2020). In fact, the combined action of standardization and flexibility required by today's production and organizational processes has meant that various profiles of knowledge workers have also fallen into those professional categories at high risk of routinization (and subsequent polarization).

From the studies by Autor, Levy and Murane (2003) and subsequent developments (Autor 2010, Goos, Manning and Salomons 2010, Autor and Dorn 2013, Goos, Manning and Salomons 2014), it emerges that employment and income polarizations are not an all-Italian prerogative: on the contrary, they find a shared origin in the outsourcing process that involved the entire world of organizations.

In some respects, some changes induced by DT have further favored the development of that gray area of difficult administration within which the canonical criteria for identifying and evaluating work performance lose their effectiveness in measuring (Bruni and Murgia 2007, Borghi and Cavalca 2015). We refer, for example, to the increasingly numerous categories of self-employed workers and, in particular, to professionals with VAT numbers, who, having difficulty entering the mechanisms of bargaining and union representation5, are increasingly forced to sell off their professionalism. (Fumagalli 2015, Papa 2021).

But precisely because this actually translates (from necessity) into virtue, it is essential to consider that DT is grafted, especially in the Italian context, into an already widely polarized socio-economic scenario, and that, given these premises, a unilateral intervention by institutions and businesses that do not adequately take into account the already complex social imbalances could only exacerbate these imbalances. Proof of this are the constant radicalization of the trade union political struggle and the growing inequalities in the distribution of wealth, the widespread paralysis of social mobility, the increase of absolute poverty itself, etc.

In addition to the new polarization induced by DT, Italy contin ues to suffer from the crystallization

Figure 4. Job Polarization: from Skill-based (SB) to Routine-based (RB) Technological change Рисунок 4. Поляризация работы: от технологических изменений, основанных на навыках (SB), к технологическим изменениям, основанным на рутинных задачах (RB)

Source: Autor and Dorn, (2013), Autor (2015).

of some well-known imbalances, compared to which decades of timid interventions and acquiescent reforms have returned a situation that has practically remained unchanged over time. The broad reference is to the phenomena of polarization and radicalization of employment, income, territorial, gender and age.

The Italian territorial composition does not draw any benefit from these reorganizations of the socioeconomic system, on the contrary. It retains a second typical polarization consisting of profound structural and infrastructural differences between regions of the North and regions of the South, as historically ascertained by the official Italian statistical institute (ISTAT 2020). Furthermore, on a more analytical level, the technological push – combined with a different capacity for innovation and investment – has led to the concentration of production value within certain hubs with a high density of human capital, generating a further intra / inter–regional polarization, even between neighboring territories, as well as between urban / metropolitan centers (digital urbanization) and rural contexts.

The technological application among knowledge workers. The impact of Remote Working on the Italian labour market during the COVID-19 pandemic

One of the most evident expressions of the technological and digital evolution has been the use of Remote Working (RW) during the COVID-19

pandemic. Without the various forms of RW, in fact, many economic activities would have been interrupted. RW in Italy has been a sort of “run for cover”, a solution to save whatever could be saved. Therefore, the number of estimated remote workers went from 570,000, in 2019, to 6,580,000, in 2020, that is over one third of the total Italian employees (Osservatorio Smart Working – Politecnico di Milano 2021).

Obviously, these solutions have been more suitable for those work contexts where workers are able to operate independently, with hardware and software equipment. Thus, it is easy to understand that big enterprises and public administration (PA) have made greater use of RW, while SMEs have had more difficulties, because of the very fact that it is often impossible to translate “physical” work activities into remote performance. It is sufficient to think about restaurants, mechanics, barbers, electricians, shopkeepers, etc., who are bound by their work context in order to be able to offer their products or services.

In those economies where it has been possible to use RW during the pandemic and especially during the “lockdown”, the main initiatives on digital technologies adopted by private enterprises and the PA have been:

-

1. Increasing in hardware equipment (due to the need for new computer stations);

-

2. Securing remote access to data and applications (i.e. cloud technologies and data warehouse);

-

3. Providing software for collaboration and communication (i.e. Zoom, Cisco Webex, Google Meet, Skype, Microsoft Teams, etc.);

-

4. Introducing of the bring your own device (BYOD) logic. This logic is a good example of the transfer of labor costs from the employer to the employee, then the computer, internet connection, air conditioning or heating, etc.

The first prolonged experience of emergency work in Italy can be summarized in the following advantages and disadvantages for big enterprises, SMEs and the PA (table 1).

As can be observed in the table 1, among the main criticalities, there is the difficulty to maintain a correct work-life balance. People who work from home are more than twice as likely to work over 48 hours per week. In the absence of clear references on working hours and conditions of availability of the worker, they constantly feel obliged to be available for the company, perhaps in answering telephone calls or in being present in front of the computer monitor (the problem of the work-life balance is more experienced among the employees of the private enterprises rather than those people employed in the PA, because the employer may request an “extra-effort” to the worker, often without recognizing overtime work).

Another critical aspect is the disparity in the workload of different people: i.e. the negative consequences on the balance between professional and private life have also affected gender inequalities, not only between men and women but also between women with or without care tasks, in particular (but not only) for children.

Particularly widespread problems concern the limited digital skills, especially among older workers.

The right to training remains an essential knot for the worker in the Knowledge Society. In fact, training is seen as an important tool to avoid that the digital skills, necessary with RW, make older or less qualified workers obsolete. For most of the workers, the training was not practiced, thus leaving the worker the additional burden of becoming literate in the use of what is necessary to work remotely. Finally, there are the problems related to the malfunction of devices and technologies.

On the other hand, among the benefits perceived by the use of RW and ICTs, there is the improvement of employees’ digital skills (specially for big enterprises and SMEs); the overcoming of bad sensations about RW (and a progressive dismantling of the prejudices related to this form of work); the re-thinking of organizational processes (including production, distribution, communication, etc.); and finally the opportunity to experience new digital tools6.

Immediately after the lockdown of 2020 (which lasted from 11 March to 3 May of the same year), not all organizations were able to resume their economic activities, because some organizations, especially some big enterprises, had to redesign their spaces in order to comply with the safety and prevention measures imposed by the Italian Government. In fact, 20% of the big enterprises decided to delay the reopening of their factories, waiting the end of summer, in September-October, while 7% of them have not reopened their offices in 2020. The main reasons of the desire to return in presence are different depending on whether we consider private enterprises or the PA.

For the private enterprises, there was the need to promote the sense of belonging of the employees; the need for socialization, for collaboration among colleagues; and the will to reduce the isolation stress.

Table 1

Main criticalities and benefits perceived by the Italian remote workers

Таблица 1

Основные критические моменты и преимущества, высказанные итальянскими удаленными работниками

|

Main criticalities perceived |

Main benefits perceived |

|

Difficulties to maintain a correct work-life balance |

Improvement of employees’ digital skills |

|

Disparities in the workload of people |

Overcoming of bad sensations about RW |

|

Limited digital skills of people (digital divide) |

Re-Thinking of company processes |

|

Problems related to technological equipment |

Opportunity to experience new technologies |

|

Increased time related to nursing work |

Saving travel time |

|

Lower income due to the lack of reimbursements |

Saving travel costs |

|

Sense of alienation and isolation |

Opportunity to choose the workplace |

|

Uncertainty about career prospects (“boundaryless careers”, Arthur and Rousseau, 1996). |

Autonomy and independence in the organization of work and tasks |

Source: Fracaro and Saldutti (2021), Osservatorio Smart Working – Politecnico di Milano (2021).

6 In this regard, it is noted that 82% of Italian workers experienced the RW for the first time in their life in the emergency phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (Osservatorio Smart Working – Politecnico di Milano 2021).

For the PA, on the other hand, there was the need for inter-functional communication (among different offices); the improvement of productivity; the collaboration among colleagues and a better control process of the workers.

Considering RW as a sort of new normal, the implementation of this widespread practice has taken place by means of the increase of working days in remote forms. This was true especially for private enterprises, that are more flexible but also less controlled. Then, there was the increase of the number of remote workers; the inclusion of new professional profiles (i.e. technicians and facilitators of change); and the increase on working hours (at the expense of the work-life balance).

In order to adapt to change, more than half of the Italian private enterprises have considered redesigning their physical spaces, considering new rules such as compulsory social distancing, sanitation measures, etc. 81% of big enterprises consider RW as part of a structured or informal working model7, and after the COVID-19 pandemic, RW will be probably kept or formalized.

The Great Resignation among Italian young workers. Another case study

The pandemic changed the attitude of many workers. In the craft society, relations were quite simple: the master craftsman taught the young apprentice the trade, who gradually gained his professional autonomy. In the industrial society, the social contract was clear: it demanded that manual workers be available 8 hours a day to carry out parceled tasks in exchange for job stability and salary certainty. In post-industrial society, on the other hand, the relations between the supply of youth and the demand for labor are much more complicated: those concerned provide their services under the required conditions in exchange for a fixed-term contract, but without any certainty, while the capitalist system offloads the responsibility for one's own labor, family and social itinerary onto the individual. Now, adults are disaffected, while young people look at job experiences with more detachment and balance.

The global phenomenon of Great Resignation (Allman 2021, Perry 2021, Parker and Clark 2022) is particularly interesting for the historical moment in which it occurs: the COVID-19 pandemic. This critical moment with dramatic consequences could have suggested a rapid return to normality, but, instead, ended up sending a great signal, which in Italy mainly saw young people as protagonists, and their refusal to submit to a renewed imbalance between employers and employees.

After this brief theoretical framework, returning to the Italian context, the Associazione Italiana per la Direzione del Personale (Italian Association of Personnel Management) (ADPI) published the results of a survey carried out on a sample of over 600 companies at the end of 2021. According to this analysis, voluntary resignations among young people in Italy affect 75% of companies.

The sectors most involved are IT and Digital (32%), Production (28%) and Marketing and Commercial (27%). It is mainly people in the age group between 26 and 35 who choose to change (or quit) jobs, which constitutes 70% of the sample analyzed, followed by the 36-45 age group. The geographic area most affected is that of companies in Northern Italy (79%), that is, the most economically developed. This trend, which took the companies involved particularly by surprise, can be traced back to three main factors:

-

■ the recovery of the labour market after the most critical phase of the pandemic (48%);

-

■ the search for more satisfactory economic conditions (47%);

-

■ the hope of finding a better work-life balance elsewhere (41%).

From these data, the deep gap between generations clearly emerges: on the one hand, there are the “children of the 1960s”, who still occupy top positions within companies, and, on the other hand, we found the “millennials” and the so-called “Generation Z” (the generation born between 1996 and 2010).

The survey shows that 25% of young people indicated the desire for a new sense of life and that 20% attributed the reason for their resignation to a negative work climate within the company.

From a social integration perspective, work is still one of the main factors, if not the most important: this means that the way society looks at us and consequently we look at ourselves, depends to a large extent on the role we play within the labour market. Proof of this is the respect (sometimes also the fear) almost always felt in front of managers, university or primary professors, while, on the opposite side, that air of sufficiency with which unfortunately one still looks at low-skilled professions, that are still considered a fallback for some and the last resort for others. In this regard, for example, we can think about the logic of “at least creating jobs”, often used to justify employment with contractual forms that no one would aspire to, which border on slavery.

The concept of work as all-encompassing is deeply rooted in the Italian culture and represents the hub from which to start looking at the relationship between two visions of the world that seem incompatible:

much of the Italian entrepreneurial success has been built on it, and, for this reason, it has been completely introjected by those who – for thirty or forty years – have entirely devoted their lives to the cause of work.

If this were not the case, we would ask ourselves how it was possible otherwise to face grueling hours, workloads that could employ more people, total absence of breaks and, in many cases, reticence towards retirement (with all the consequent damage to physical and psychological health). This attitude, which often concerns those in managerial roles, does not spare those in subordinate positions. At the base of a typically twentieth-century work ethic for which it is in work that individual existence is given entirely, everything else appears as a surplus, habit (not to say vice), a complementary activity that falls into the category of hobbies, pastimes, and then automatically into what is “of less value”.

The problem that arises is that in this vision of work – in the light of which young people who do not want to submit to it are accused of being fickle, irresponsible and not very passionate – it is the result of a precise culture and society, without a shadow of a doubt in crisis.

If we analyze the causes that the same ADPI report identifies as responsible for voluntary resignations, we immediately notice how both the economic issue and the better balance between private life and office are two needs that clash with the traditional imaginary of work. In the first case, because the demand for adequate salaries, due to the awareness that one is exchanging one’s life time for a sum of money, calls into question the passage of the apprenticeship, which has always been considered obligatory. Hence the accusation of impatience: in the eyes of the average entrepreneur, young people “want everything immediately”, they would not be able to wait and respect the path that was followed by others before them.

In the second case, the desire to defend one’s private sphere (or at least to build one) collides with the primacy of work, never questioned by those who have always seen it as their only place of existential legitimacy.

Therefore, if total devotion to work is no longer taken for granted and the factory or office is no longer the only place to build oneself, and at the same time the employment system remains unchanged, the only escape route becomes the change of direction. A perpetual movement in search of the place that is most able to hold together those aspects of one’s being that go beyond work in the strict sense.

This can result both in the demand for an adequate balance between private life and work, and in the search for unstructured work contexts, where organizational networks supplant the antiquated corporate hierarchies (albeit considering what we have previously stated about dysfunction in the RW). The risk is to look at distant models and expectations that lead to a structural misunderstanding. Indeed, the categories with which the two generations in the field look at the world seem incompatible: the overlap between employment and identity no longer belongs to the new generation of Italian workers (both millennials and Gen Z), who have no intention of postponing their existence “until later” and, in the event that it is forced to do so, it requires at least to be adequately “reimbursed”.

Occupation in time of COVID-19 pandemic is a priority issue, and it would be useless to dismiss it on the basis of simplistic readings and mutual accusations. Thus, the lack of communication that characterizes this intergenerational relationship on a hot topic like work cannot, however, be quickly liquidated. If on the one hand, the demand for workforce is still in the hands of those who insist on perpetuating an outdated model of work organization, on the other hand, those who can answer this question today do not seem to have intention to yield under the conditions that model implies.

Given that no one doubts the importance of work as a structural dimension of any social context, the outcome of the clash cannot be an aut aut between work in its “twentieth-century typical form”, now exhausted, or unemployment. It would be a disadvantageous result for both parties. A first step could be to begin to understand situations different from one’s own, consequently changing the narrative about undecided young people, whose poorly considered choices would appear to be symptoms of immaturity, and to ask oneself how a workplace can, today, be totally attractive.

They can be willing to receive a lower salary if this implies a greater adherence between the meaning of the work that is being done and the direction they want to give to their life, but this does not mean that they are willing to accept any sum regardless.

The radical change of perspective offered by new workers represents a breaking point and, as often happens, historical events can be considered in at least two different ways: either as a source of stalemate (an undesirable status quo ), thus persisting always in the same obsolete direction; or as a turning point, an opportunities to change course, review the route and discover that the destination is not immutable.

Conclusions

Despite we can talk about an effective and unquestionable progress thanks to the use of digital technologies, which in many ways improve our quality of life (and our resilience during the pandemic), we must be attentive also to the dangers that technology potentially incorporates, including those risks for the world of work, of which we have given some examples.

In the previous pages we have attempted to briefly retrace the salient passages of recent international and national literature in relation to job polarization in the business world, RW and new imbalances between employers and employees. In this context, the center of gravity of the professional axis is moving downwards, so much so that we are talking about a new low-skill equilibrium, in the sense that low-skilled (often low-wage) activities are increasing, but also routine and intermediate ones. In this last case, the contingent of knowledge workers is also affected, including those who during the pandemic (and many still now) are working with various RW modalities. This affects the type of bargaining, which therefore also affects the most skilled workers. Not infrequently, this takes the form of flexible types of contracts, which take on real forms of exploitation that are harmful to human dignity.

From here, derive two synthetic considerations, one on the contents, and the other on the social actors. From the literature examined and from the observation of the Italian case, it seems to look at the worker skills package in a way that is not always exhaustive, as if these could be measured with an engineering logic. The notion of competence has a qualitative construct in itself as well as a quantitative one, for which it would be necessary to consider more carefully, in addition to the hard part of the work (the executive, performative, implementing), also the soft one (communicative, relational, cognitive), which contributes to the determination of the tasks performed, all the more so in a period so full of transformations as the one in progress.

The other consideration concerns the employees, that is, the resilience of the middle class. As we have observed so far, a good ninety years have passed since the thesis suggested by the German sociologist Siegfried Kracauer (1996) on the proletarianization of clerkships, history seems to agree with him: these subjects seem to lose positions in the hierarchical ladder in terms of status, labour and market, while a small share is gaining ground upwards.

If this photograph corresponds to the ongoing processes, this means that the middle class is drying up, with serious consequences on the level of social polarization, but even more so on that of political radicalization. The consequences, as we have noted, are varied, and also include what has been called Great Resignation.

On the basis of these observations, to draw some concluding lines, we can affirm that the new world needs a new social pact which, for now, cannot even be glimpsed on the horizon. While in industrial capitalism based on the Taylor-Fordist philosophy it was clear – a system of reciprocity between high wages and little / no expectations in terms of professional content – the capitalism in vogue, on the other hand, shattered the pact just mentioned but did not it has replaced some (Polanyi 2001). There is no counterpart to job polarization, so a business model capable of finding shared mediations in relation to the contradictions we have tried to pose should be faced with a multiplicity of professional profiles, which, instead, are progressively downgraded or even disappear from complex organizations.

The most significant empirical evidence given is the social distancing between stable and precarious, between qualified and unskilled, between guaranteed and unsecured. In this complex game, the risks underlying the great changes induced by new technologies call into question the responsibilities of institutions, social bodies, and businesses.

Список литературы The urgency to imagine a new paradigm. The labour market between global trends and peculiar Italian features after the COVID-19 pandemic

- Acemoglu D., Restrepo P. Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets. Journal of Political Economy. 2020;128,6:2188. DOI: 10.1086/705716

- Allman K. Career matters: 'The great resignation' sweeping workplaces around the world. LSJ: Law Society of NSW Journal. 2021;81:46. DOI: 10.3316/agis.20211109056610

- Arthur M.B., Rousseau D.M., eds. The Boundaryless Career: A New Employment Principle for a New Organizational Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 1996.

- Astrologo D., Surbone A., Terna P. Il lavoro e il valore all'epoca dei robot: Intelligenza artificiale e non-occupazione. Sesto San Giovanni: Meltemi: 2019.

- Autor D.H. The Polarization of Job Opportunities in the U.S. Labor Market: Implications for Employment and Earnings. Center for American Progress and the Hamilton Project: 2010. Https://economics.mit.edu/files/11589 (21/02/2022).

- Autor D.H. The 'Task Approach' to Labor Markets: An Overview. Journal of Labour Market Research. 2013;46:185. DOI: 10.1007/ s12651-013-0128-z

- Autor D.H. Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2015;29,3:3. DOI: 0.1257/jep.29.3.3

- Autor D.H., Dorn D. The Growth of Low-Skill Service Jobs and the Polarization of the US Labor Market. American Economic Review. 2013;103,5:1553. DOI: 10.1257/aer.103.5.1553

- Autor D.H., Katz L.F., Kearney M.S. The Polarization of the US Labor Market. American Economic Review. 2006;96,2:189. DOI: 10.1257/000282806777212620

- Autor D.H., Levy F., Murane R.J. The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2003;118,4:1279. DOI: 10.1162/003355303322552801

- Bai C., Dallasega P., Orzes G., Sarkis J. Industry 4.0 technologies assessment: a sustainability perspective. International Journal of Production Economics. 2020;229, 107776.

- Beier G., Ullrich A., Niehoff S., Reißig M., Habich M. Industry 4.0: how it is defined from a sociotechnical perspective and how much sustainability it includes - a literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2020;259,120856.

- Bonivento C., Gentili L., Paoli A. Sistemi di automazione industriale. Architetture e controllo. Milano: McGraw-Hill: 2011.

- Borghi P., Cavalca G. Frontiere della rappresentanza: potenzialita e limiti organizzativi dell'offerta rivolta ai professionisti indipendenti. Sociologia del lavoro. 2015;140:115. DOI: 10.3280/SL2015-140008

- Bruni A., Murgia A. Atipici o flessibili? San Precario salvaci tu!. Sociologia del lavoro. 2007;105:64. DOI: 10.1400/94229

- Brynjolfsson E., McAfee A. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. New York: W.W. Norton & Co: 2014.

- Castells M. La nascita della societa in rete. Milano: EGEA: 2014.

- CEDEFOP. Skill Forecast. Trends and Challenge to 2030. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union: 2018. Https:// www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/3077_en.pdf (21/02/2022).

- Cirillo V., Guarascio D. Jobs and Competitiveness in a Polarised Europe. Intereconomics. 2015;50:156. DOI: 10.1007/s10272-015-0536-0

- Daugherty P., Wilson J.H. Human + machine: Ripensare il lavoro nell'eta dell'intelligenza artificiale. Milano: Guerini Next: 2019.

- Drucker P. The Age of Discontinuity. Guidelines to Our Changing Society. London: Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd: 1969.

- Eurofound. Occupational Change and Wage Inequality: European Jobs Monitor 2017. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union: 2017.

- Falcone R., Capirci O., Lucidi F., Zoccolotti P. Prospettive di intelligenza artificiale: mente, lavoro e societa nel mondo del machine learning. Giornale italiano di psicologia. 2018;1:43. DOI: 10.1421/90306

- Fondazione Ergo. Superare il low-skill equilibrium. Quaderno di approfondimento n.3: 2019. Https://www.fondazionergo.it/ uplo ad/p df/Quaderno_Skills_res.p df (21/02/2022).

- Ford M. Il futuro senza lavoro. Accelerazione tecnologica e macchine intelligenti. Come prepararsi alla rivoluzione economica in arrivo. Milano: il Saggiatore: 2017.

- Fracaro M., Saldutti N. Lavorare da casa. I diritti (e i doveri) dello smart working. Orario di lavoro e straordinari, buoni pasto, benefit, salute e organizzazione dello spazio. Le regole per il lavoro da remoto. Milano: RCS Mediagroup: 2021.

- Frey C.B., Osborne M.A. Technology at Work. The Future of Innovation and Employment. Oxford: Oxford Martin School: 2021. Http://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/re-ports/Citi_GPS_Tech nology_Work.pdf (25/02/2022).

- Frey C.B., Osborne M.A. The Future of Employment: How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerisation?. Oxford: Oxford Martin School: 2015. Http://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/down-loads/ academic/The_Future_of_Employment.pdf (25/02/2022).

- Frey, C.B. La trappola della tecnologia. Capitale, lavoro e potere nell'era dell'automazione. Milano: FrancoAngeli: 2020.

- Fumagalli A. Le trasformazioni del lavoro autonomo tra crisi e precarieta: il lavoro autonomo di III generazione. Quaderni di ricerca sullartigianato. 2015;2:225. DOI: 10.12830/81143

- Gallino L. Il lavoro non e una merce. Contro la flessibilita. Roma-Bari: Laterza: 2007.

- Ghobakhloo M. Industry 4.0, digitization, and opportunities for sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2020;252,119869. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119869, EDN: RMOPQC

- Goos M., Manning A., Salomons A. Explaining Job Polarization in Europe: The Roles of Technology, Globalization and Institutions. Centre for Economic Performance: 2010, Discussion Paper No 1026. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.1983952.

- Goos M., Manning A., Salomons A. Explaining Job Polarization: Routine Biased Technological Change and Offshoring. American Economic Review. 2014;104,8:2509. DOI: 10.1257/aer.104.8.2509

- ILO. What Are the Effects of Job Polarization on Skills Distribution of Young Workers in Developing Countries?. International Labour Organization Youth Employment Programme: 2016. Http://www.ireg.ch/doc/etudes/2016-ILO-technical-brief-7.pdf (21/02/2022).

- ISTAT (Italian National Institute of Statistics). Livelli di istruzione e ritorni occupazionali: 2020. Https:// www.istat.it/it/files/2020/07/Livelli-di-istruzione-e-ritorni-occupazionali.pdf (21/02/2022).

- Jabbour A.B.L.d.S., Jabbour C.J.C., Foropona C., Filho M.G. When titans meet - can industry 4.0 revolutionise the environmentally-sustainable manufacturing wave? The role of critical success factors. Technology Forecasting & Social Change. 2018;132(1):18-25.

- Kracauer S. The Salaried Masses: Duty and Distraction in Weimar Germany. London, New York: Verso: 1930.

- Lucchese M., Nascia L., Pianta M. Industrial Policy and Technology in Italy. Economia e Politica Industriale. 2016;43:233. DOI: 10.1007/s40812-016-0047-4

- Marzano G. Intelligenza artificiale e mercato del lavoro: il recente dibattito americano, Economia & Lavoro. 2016;2:159. DOI: 10.7384/84409

- Mazzucato M., Cimoli M., Dosi G., Stiglitz J.E., Landesmann M.A., Pianta M., Page T. Which Industrial Policy does Europe Need?. Intereconomics - Review of European Economic Policy. 2015;50,3:120. DOI: 10.1007/s10272-015-0535-1

- Müller J.M., Voigt K.I. Sustainable industrial value creation in SMEs: a comparison between industry 4.0 and made in China 2025. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing-Green Technology. 2018;5(5):659-670. EDN: FIMRDJ

- Osservatorio Smart Working - Politecnico di Milano: 2021. URL: https://www.osservatori.net/it/ricerche/osservatori-attivi/smart-working. (20/02/2022).

- Papa V. Working (&) poor. Dualizzazione del mercato e lavoro autonomo povero nell'UE. Rivista del Diritto della Sicurezza Sociale. 2021;1:49. DOI: 10.3241/100012

- Parker R, Clark B.Y. Unraveling the Great Resignation: Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Oregon Workers: 2022. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.4019586

- Perry T.S. Tech Pay Rises (Almost) Everywhere: The 'Great Resignation' is pushing salaries up. IEEE Spectrum. 2021;58,12:17. DOI: 10.1109/MSPEC.2021.9641775

- Polanyi K. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Boston: Beacon Press: 2001.

- Posada, J. From Development to Deployment: For a Comprehensive Approach to Ethics of AI and Labour: 2020. AoIR 2020: The 21th Annual Conference of the Association of Internet Researchers. Https://spir.aoir.org/ojs/index.php/spir/article/view/11307/9981. (21/02/2022).

- Rullani F., Rullani E. Dentro la rivoluzione digitale. Per una nuova cultura dell'impresa e del management. Torino: Giappichelli: 2018.

- Salento A., eds. Industria 4.0: Oltre il deterninismo tecnologico. Bologna: TAO Digital Library: 2018.

- Steinhoff J. Automation and Autonomy Labour, Capital and Machines in the Artificial Intelligence Industry. New York: Palgrave Macmillan: 2021.

- Taylor F.W. The Principles of Scientific Management. New York-London: Harper & Brothers: 1911.

- Treccani. Lessico del XXI secolo: 2013. Https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/occupabilita_%28Lessico-del-XXI-Secolo%29/ (21/02/2022).

- Unioncamere - ANPAL. Sistema informativo Excelsior. Previsione dei fabbisogni occupazionali e professionali in Italia a medio termine (2018-2022): 2018. Https://excelsior.unioncamere.net/ images/pubblicazioni2017/report-previsivo-2018-2022.pdf (21/02/2022).

- Unioncamere - ANPAL. Sistema informativo Excelsior. Previsioni dei fabbisogni occupazionali e professionali in Italia a medio termine (2020-2024): 2020. Https://excelsior.unioncamere.net/images /pubblicazioni2020/report-previsivo-2020.pdf (21/02/2022).

- Urbinati A., Chiaroni D., Chiesa V., Frattini F. The Role of Digital Technologies in Open Innovation Processes: An Exploratory Multiple Case Study Analysis. R & D Management. 2020;50,1:136. DOI: 10.1111/radm.12313.

- Van Dijck J.F.T.M., Poell T., de Waal M. Platform society. Valori pubblici e societa connessa. Milano: Guerini Scientifica: 2019.

- Vivarelli M. Technology, Employment and Skills: An Interpretative Framework. Eurasian Business Review. 2013;3:66. DOI: 10.14208/BF03353818.

- World Economic Forum. The Future of Jobs Report 2018: 2018. Http://www3.weforum.org/docs/ WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2018.pdf (21/02/2022).

- World Economic Forum. The Future of Jobs Report 2020: 2020. Http://www3.weforum.org/docs/ WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2020.pdf (21/02/2022).