Transformation of gender power disposition in modern families as a driving force of institutional changes

Автор: Bazueva Elena Valerevna

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social development

Статья в выпуске: 4 (34) т.7, 2014 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article uses the synthesis of the institutional theory tools and synergetics for analyzing the need to optimize the existing system of gender power institutions in the modern Russian economy. It is known that the performance effectiveness of the projected institutions is determined by the fact that economic agents are in need of such changes. In this regard, the article is focused on a study of the processes of transformation of the traditional type of gender power disposition in Russian families. It has been determined that they are characterized by a more equal distribution of functions in the organization of household. Therefore, currently, along with the traditional type of gender power, we define two more types: the egalitarian type, when the interests of both spouses are considered and there is symmetry in the distribution of household responsibilities, and the transitional type (interim version of gender interactions between spouses). The family is considered as a closed and an open system for determining the efficiency of reproduction of these gender power types in the modern economy...

System of institutions, institutional changes, gender power institutions, gender relationships in the family

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223614

IDR: 147223614 | УДК: 330.837: | DOI: 10.15838/esc/2014.4.34.12

Текст научной статьи Transformation of gender power disposition in modern families as a driving force of institutional changes

As we have discovered in [3, 5, 6], the current system of gender power institutions1 is of very low quality, it does not meet the requirements of modern economy and reduces the performance of the entire socioeconomic system. Following the standards of behavior (institutional roles) established by this system of institutions is very costly for economic agents at all its levels [2]. All this determines the necessity of modernization of the existing system of gender power institutions towards increasing the degree of its egalitarity2.

In our opinion, in order to define possible ways to optimize this institutional system one should use the tools accumulated by economic theory for the analysis of institutional change.

In this regard we remind that at present “there is a significant number of structuring processes of institutional design that differ in details”; most of them represent a special case of the general logic of decision-making process and its principles (see, e.g. [25, p. 18]). Among them we can distinguish the approach by O.S. Sukharev, who believes that institutional planning should be based on the following principles (criteria): setting of goals; identification of areas for application of efforts; functional diversity; the costs of the actions of institutions and agents, arising from the introduction of new institutions; the period of functioning of an institution and the time before its modification, substitution, elimination or correction; resistance to external changes and resistance to spontaneous mutations, as well as financial aspects of functioning of a newly established institution.

Besides, the latter principle is not the same as the cost of functioning of an institution, but rather the increment of financial opportunities that occur or do not occur with the introduction of this institution, or the required amount of cash collateral per unit of time, necessary for the most effective functioning of an institution [24, p. 109]. Note that the above mentioned institutional planning criteria practically correspond to the set of qualitative characteristics of effective functioning of an institution, in other words, its functionality.

The author clarifies that the application of these principles will help to reduce the number and depth of dysfunctions in the economy. Therefore, one of the first stages of institutional planning should be “definition of initial institutional quality of a system, the extent of its dysfunctionality according to basic institutions (rules), and also clarification of the necessity for any changes, institutions, including the possibility of borrowing institutions, transferring them from a different socio-economic environment” [24, p. 110]. The approach to the stages of institutional design has been used in this study.

The quality level of Russia’s system of gender power institutions and the costs associated with its functioning for economic agents at all its levels have been studied in previous works of the author in [2–6], therefore, in this article we shall take a closer look at the definition of economic agents and the extent of their demand for the introduction of the system of gender power institutions of egalitarian type. We emphasize that according to the logic of the process of institutional changes proposed by D. North and developed at present by representatives of institutional economic theory, the degree of coincidence of reformers’ intentions in the creation of new institutions and beliefs of economic agents will determine the effectiveness of performance of a projected institution [18, pp. 80-93].

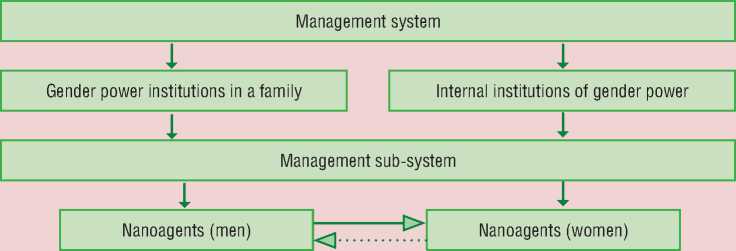

In this regard, we recall that in the modern Russian economy the maximum degree of gender power concentration is achieved at the lower levels of the hierarchy of the system of gender power institutions – in the institution of family power as represented by its head and the institution of internal power (see more on the subject in [3]). It is no coincidence that family economy is called as the “social space, in which gender roles are distinguished to the greatest extent” with the highest degree of interdependence of men and women due to their marital status or blood relation [16, p. 97]. However, as A. Toffler points out, a new civilization brings with it a new economy, new political conflicts, changed ways of working, loving, and living and beyond all this an altered consciousness and new family styles. [26, p. 31, 34]. We shall see if it is really so. For this purpose we shall imagine a family and its gender power institutions as a closed system, i.e. we shall eliminate the influence of external institutions of gender power on the determination of the disposition of power within the family. This interaction process is presented as a scheme in figure 1 .

The figure shows that the objectives of life behavior of men and women in the family are determined by the management system that consists of a family’s gender power institution represented by its head and internal institutions of gender power. We remind that each of them in accordance with their own disposition of power determines the institutional role that the subjects of gender interaction must implement within the existing institutional environment. The content of the disposition of gender power by the head of the family includes: 1) clear division

Figure 1. Structure of subordination of the purposes of life behavior of men and women in a family*

* Solid line denotes real connections of power impacts, dotted line denotes nominal connections that are characteristic of a minor part of modern Russian families.

of household responsibilities on the basis of gender; 2) conformity with the stereotype of family breadwinner when choosing the type of family, forms of leisure and spheres of professional activity by the object of power. This type of gender power disposition, in the terms used by genderologists, corresponds to the traditional type of family, when the man acts as the subject of gender power, and the woman – as its object. Consequently, the disposition of gender power assumes the following distribution of roles: the man is the breadwinner in a family, the earner of market capital, and the woman focuses her efforts on the accumulation of “family” capital. It is acceptable that a woman is employed in the public sector of the economy. However, household management is her priority. It should be noted that such distribution of household chores, according to G. Becker, contributes to the stability of marriage, since the expected utility from housekeeping in women is greater than the utility of their work in market production. On the one hand, this can be explained by lower wages of women in the labor market, and on the other hand, by the illiquidity of housework in the absence of generally accepted criteria for evaluating this type of employment in society. Therefore, housekeeping is valuable only for a specific family, which fundamentally distinguishes it from the type of resource such as money that the “breadwinner” can offer for exchange. However, even in the given family, the value of time spent on housework, compared with working time, will be always lower, because this type of employment is carried out in free time (at weekends or in the evening), when “the relative importance of lost earnings proves to be lower” [9, p. 171]. Though at present, according to many studies, Russian families are going through the process of transformation of this type of gender power disposition. The results of our longitudinal survey of families in Perm Krai in 2001–2011 confirm this trend3.

Table 1. Dynamics of modernization of the traditional type of gender power in family economy in 2001–2011

|

Variants of distribution of housework |

2001 |

2006 |

2009 |

2011 |

|

1. There is a clear division of labor by gender and age |

12.30 |

15.92 |

39.70 |

30.40 |

|

2. The whole family is equally involved in household chores |

41.04 |

46.02 |

31.90 |

48.63 |

|

3. The main burden falls on the woman – mother |

41.90 |

34.36 |

26.06 |

15.90 |

|

4. All housework is done mostly by parents of the husband or wife |

0.00 |

2.42 |

0.00 |

3.13 |

|

5. Father and mother prefer to do most of the housework themselves |

4.76 |

1.38 |

2.34 |

1.94 |

The dynamics of distribution of functions on the distribution of household chores between members of respondents’ families is presented in table 1 .

The table allows us to say that modern families in Russia and its regions are characterized by a tendency toward a more even distribution of functions in the household, on the one hand, by reducing the proportion of families in which these functions are performed only by women, and increasing the share of families with a clear gender division of labor in the family economy; on the other hand, by the increase in the share of families with proportional load on all of their members. The wavelike change in the data presented in the table is due to the dynamics of indicators of the national economy development: when Russia’s economy is in the stage of moderate growth, families are characterized by a more even distribution of functions on the organization of family economy, including by increasing opportunities of obtaining these services in the public sector. And conversely, a decline in living standards of households increases the time spent by men and women on household chores in a family. Then let us carry out a detailed analysis of the time spent on housework in families of respondents; it is presented in table 2. It ranks prevailing positions of each family member depending on his/her contribution to the performance of household chores. The table confirms the above conclusion concerning a more balanced distribution of domestic chores in Russian families through increased participation of men and children. As a result, the ratio of time spent on housework by men and women has decreased almost twice over ten years – from 2.95 to 1.75. Let us highlight positive trends in the redistribution of household chores between spouses.

The first trend: there has been a twofold reduction in gender imbalances concerning the time spent on cooking and washing dishes. In our opinion, this is connected with servicization of economy in Russia and its regions; more specifically, the development of fast food network. Note, also, that within a household the amount of time that men spend on cooking in 2001–2011 increased by 9 minutes a day, while for women, on the contrary, it decreased by 9 minutes. In our opinion, this is a positive change, though it is little; this change can gradually break the traditional gender stereotype that “a woman’s place is in the kitchen”.

The second trend : the ratio of time spent by men and women on the purchase of goods and products has reduced. Moreover, it increased more rapidly in men than in

Table 2. Dynamics of distribution of chores in households of respondents, hours a day

The third trend: modern families gradually abandon the feminization of children’s education due to the formation of an institution of “new fatherhood”. As S.A. Orlyanskiy points out, the duties of the “new father” include child care, moral and intellectual education of the child from the moment of his/her birth. However, the author stresses that a father is not a “householder”. He works, earns money and devotes his free time to the child. A man assumes part of household chores related to family communication, i.e. a man, along with implementation of his institutional role of breadwinner in the family, is actively engaged in education of the children [20].

For example, the amount of time, which men spend on education of their children in 2001–2011 increased by 13 minutes. However, we note that the intensification of men’s participation in education of children that we pointed out in 2006, when men devoted their attention to their children even by four minutes per day more than moms, slowed down under the impact of the state and regional policy aimed at stimulation of birth rate. So, for example, as a result of implementation of the regional project “Provision of allowances for families with children of 18 months –5 years old, who do not attend a municipal preschool educational institution” more than 60% of mothers of children aged under 5 do not go back to work when their child care leave is over.

The fourth trend: the data obtained in the course of our research refute the assessments of many scientists, who indicate that women, rather than men, are more likely to render assistance to their relatives. For example, according to the time spent on this kind of housework, men have retained leadership since 2006, though it is not significant.

The fifth trend: in 2001–2011 the ratio of time spent on laundry, sewing, taking care of linen, clothing and footwear slightly decreased (from 2.69 to 2.00). At that, the time that men, as well as women, spent on this type of housework has increased over 10 years (16 and 21 minutes, respectively). In our opinion, the reduction in the amount of time spent on these chores is hampered by poor development of consumer services sphere in Russia’s regions and also by high prices for already existing types of consumer services.

The sixth trend: the increase in the level of mechanization of family economy is accompanied by greater participation of men in cleaning the rooms, taking care of furniture and household appliances. For example, in 2011 men and women spend almost the same amount of time on this type of housework (the ratio of time spent amounted to 1.12).

After highlighting the above positive trends in redistribution of household responsibilities between spouses, genderologists define transitional and egalitarian types of gender interactions along with the traditional type. Families with egalitarian internal structure are characterized by fair, proportional distribution of family responsibilities, interchangeability of spouses in solving everyday problems. Under egalitarian conditions there are no gender-differentiated responsibilities; decisions are discussed and made by all family members.

This type of gender interaction is possible only in conditions similar to those of competitive environment, when the degree of concentration of gender power is insignificant, since it is limited by the freedom of another economic agent. In this case the market becomes the subject of gender power, and men and women are rationally acting individuals in the marriage market. In the light of methodology of institutional economic theory this means the presence of the best marriage market, which provides all its participants with imputed income or “prices” that serve as incentives for entering an appropriate marriage. “Imputed prices” are also used when selecting the “quality” of a future partner.

G. Becker notes that “men and women of higher quality marry their own kind and they do not choose partners of lower quality when these qualities are complementary. The choice based on similarity is optimal, when the characteristics are complementary, and the choice based on difference is optimal, when they are interchangeable, since the partners of high quality in the first case reinforce each other’s characteristics, and in the second – duplicate them.

G. Becker explains further: “...When the characteristics are complementary, the benefit from marrying the woman of this quality is greater for a high-quality man; and the benefit is greater for a low-quality man, when the characteristics are interchangeable” [9, p. 390]. We use this concept to study the ratio of egalitarian to traditional types of gender power that women and men have in a family. In accordance with the gender research methodology, low-quality men and women are those, who prefer the traditional disposition of gender power. In turn, high-quality men and women prefer the egalitarian type of gender interaction.

We agree with G. Becker, who states that a set of equilibrium incomes is the criterion of optimal sorting of economic agents in the marriage market. In this case there are no opportunities for the formation of costs associated with the presence of elements of power in the transactions between them (costs of subordination and costs of refusal; see more on the subject in [3]). This is possible due to the reduction (or impossibility of formation) of costs of subordination and costs of refusal in the levelling of the influence of internal institutions of gender power in men and in women, the operation of which results in “understatement of one’s own price” in the marriage market in women and, on the contrary, “overpricing” in men, when women initially choose lower quality men (with the traditional type of gender power disposition). In this regard, Becker points out that “some participants choose partners that are of the worst “quality” because they believe the partners of “the best quality” are too expensive” [9, p. 381], in other words, unaffordable.

And now let us define the number of women who have an opportunity to do an optimal sorting of economic agents in the marriage market according to the criterion of balanced incomes, and hence to form the disposition of gender power of the egalitarian type. We begin with the fact that the main source of income of men and women in contemporary Russia is salary that is segmented by gender.

Therefore, it is necessary to determine the economic agents, for which an independent activity has become more effective. In our opinion, they can include women employed in top management with high salaries. For example, according to a monitoring of the labor market for top managers in Russia (2000–2007) carried out by the Laboratory for Labor Market Studies at the Higher School of Economics, the share of women in senior leadership positions in 2000–2007 was growing steadily – this indicator in Russian companies increased from 5.2% in 2000 to 20.1% in 2007, and in foreign companies – from 14 to 23.2%, respectively [20, p. 53].

The category of women able to conduct their own activity independently from their husbands, in our opinion, can also include female employers. According to a population survey of employment issues, their share among employed women in the Russian labor market in 2010–2012 was about 1%. In addition, modern families with average and high incomes commercialize everyday life (care)4 by using hired labor (babysitters, housekeepers). For example, according to a research by O.B. Savinskaya, in 2010 16.1% of respondents were using and are using the services of babysitters [15, p. 84].

It appears that the tendency towards egalitarization of gender interactions between spouses will only increase in the future, because at present, according to numerous studies, there is an increase in the share of citizens (especially young ones), who support individualism, and focus on the pragmatic ideal of a self-sufficient and successful person able to achieve material well-being and good social status. For example, according to the Public Opinion Foundation there are 18% of such people in Russia5.

Note that these ideals correspond to the characteristics of the Y-matrix, based on a high level of autonomism of economic agents, i.e. the priority of “I” over “We”, when there is a primacy of an individual, his/her rights and freedoms with respect to the values of communities of a higher level. The subjects in such conditions are dissociated and can function on their own, separately from each other [13]. This autonomism of economic agents implies a high level of development of civil society, which, in the opinion of many genderologists, is a prerequisite for the development of gender-parity relations in national economy.

As for the transitional type of gender power disposition typical of contemporary Russian families, we think that it represents an intermediate option of gender interactions between spouses, when the effect of the institute of internal power is reduced through the weakening of stereotypes of the condition and changes in gender status of economic agents.

This type of gender power disposition is characterized by the following: 1) reduction in the concentration of gender power of

Table 3. Dynamics of priorities in the formation of income in families, %

|

Whose incomes form the major part of your family’s budget? |

2001 |

2006 |

2009 |

2011 |

|

1. Husband |

29.7 |

44.6 |

39.8 |

43.6 |

|

2. Wife |

34.2 |

26.9 |

27.2 |

31.6 |

|

3. Children |

13.9 |

8.9 |

10.2 |

4.5 |

|

4. Retired parents |

9.2 |

3.1 |

5.5 |

2.9 |

|

5. Support from our relatives |

8.6 |

2.2 |

2.4 |

1.51 |

|

6. The incomes are similar |

4.4 |

14.3 |

14.9 |

15.89 |

men in the family economy as a result of their greater involvement in housework; 2) enhancement of the role of women in making decisions that are important for the family (matriarchal family pattern).

In the first case, in our opinion, the object-subject type of gender interaction can be determined individually in each family (biarchial type of gender power disposition). In this regard, for example, V.A. Ramikh notes that “today the ideals of masculinity and femininity are more contradictory than ever: their traditional and modern characteristics are intertwined, they take into account the diversity of individual variations much better than before. The general trend of development in this sphere consists in weakening the polarization of gender roles and socio-cultural stereotypes associated with them. In these conditions, social roles of men and women do not seem polar and mutually exclusive any longer, the possibility of various individual combinations is emerging” (cit. from [20]).

Institutional roles of economic agents in the matriarchal type of gender power are redistributed; women in such families act as the subject of gender power, and men – as its object. In this case, women become main breadwinners in the market of capital; as for men, they are mostly engaged in accumulation of specific “family” capital. Maximization of utility is achieved in the case, when the man’s wage is significantly lower than that of the woman6. Our study shows that there are about 30% of such families in Perm Krai (tab. 3). A common situation for the matriarchal type of family is when it is men, who take a childrearing leave. According to HeadHunter company, nowadays in Russia the share of such families is about 7% [8].

Next, in order to determine the quantity demanded for the institutions of gender power of egalitarian type among economic agents, we shall use one of the basic principles of synergetics, which assumes that a highly synergetic system should have indispensable mutual cooperation and assistance, i.e. the coherence of behavior between its individual components [10, p. 387]. From this perspective, two main types of interaction are possible: 1) coordinated interaction, provided that there is coherence in the conditions of power disposition defined by the institution of power represented by its head and the institution of internal power; 2) uncoordinated interaction that implies their inconsistency. We think that traditional and egalitarian types of gender power in a family from these positions are coordinated, and the transitional type admits both variants of interactions.

Under the traditional type of gender interaction both women and men must be satisfied with gender-differentiated division of labor in the family economy. Research results show that 26% of respondents prefer the traditional family model, among them 15% are young women and 85% – young men [21]. At the same time, if we process this data using the ratios of positional consent, then consonant positions (coordinated patterns of gender behavior) will be characteristic only for 3% of respondents’ answers. In view of the above and taking into account the results of other studies, we can point out that the traditional type of gender power is established not more than in 20–25% of contemporary Russian families.

The model of egalitarian relations is gender-balanced (coordinated), since the interests of both spouses are taken into account, and there is symmetry in the distribution of household responsibilities. At that, the choice made by each family member concerning what to do (to work in the market sector or in the household), depends on the ratio of earnings in the labor market, the opportunity cost of production of goods in the household and egalitarian attitudes of spouses’ behavior. According to our estimates, the share of such families in contemporary Russia is about 15%.

The “transitional” type of coordinated relations is observed in families where both spouses are satisfied with the reduction in the degree of concentration of gender power of men in the family economy as a result of their greater involvement in the household or enhancement of the role of women in making decisions important for the family (matriarchal family model).

The disagreement in the transitional type of gender power disposition can be manifested in the case when at least one of the spouses is not satisfied with participation in the accumulation of a specific market or “family” capital, i.e. the internal attitudes of nanoagents do not coincide with the disposition of gender power imposed on them by the head of the family. According to many studies, this type of gender interactions is, unfortunately, typical of the majority of Russian families. Apparently, as M.Yu. Arutyunyan points out, the “gender misfortune” of Russian families consists in a contradictory combination of patriarchal (in men) and egalitarian (in women) gender agreements [1]. As a result, young couples in particular have a low degree of satisfaction with marriage and, consequently, high rate of divorce, by which Russia ranks first in the world. Moreover, the mismatch between gender power disposition in Russian families is intensifying. For example, the content analysis of 32 projective compositions “My future family” carried out by S.V. Zaev in 2005 shows that almost 40% of female respondents prefer egalitarian gender contracts in the family, where relations are based not on material wealth and clear division of power resources, but on a high level of psychological compatibility.

In contrast, the majority of young men (75%) have traditional understanding of family economy: they assume the role of head and breadwinner, and they expect to receive psychological, emotional and sexual support in return [11, p. 28-29].

The data obtained in the course of research by T.G. Pospelova and processed using the program Kobra-KD7, show that 87% of girls preferred the egalitarian type of gender interaction in 2008 [21, p. 48].

However, most women and men, who prefer the egalitarian type of gender power in family economy, are characterized by a mismatch in the general system of institutional roles due to the incoherence of the disposition of power at each level of the hierarchy in the system of gender power institutions (see more on the subject in [3, 5]).

For example, the findings of our research into gender characteristics of personality8 carried out from the 2011–2012 academic year onward and used annually as input control of knowledge in the study of the course “Gender studies and feminology” show that the majority of young women and men, on the one hand, believe that a desire to make a career, high professionalism, success in business, leadership in any field should be typical both for women and men; they emphasize that “the established tradition of promoting men to senior positions is deprecated, and it is both men and women that should be able to take managing positions on an equal basis”; and they do not agree that “a woman is first of all a mother, and her most important purpose is to give birth and to raise children”. This role is more important than all of her other roles”.

On the other hand, they point out that “biological sex determines the differences in the opportunities for men and women in different spheres of life; consequently, some gender-related limitations are still necessary, “it is right that there are such spheres, in which the participation of women should be limited (for example, in politics, diplomacy, and others) and, as a consequence, “for women the most important thing is family”. Moreover, the attitudes of girls in their answers are more controversial than those of young men.

As a result, psychologists state that modern men and women in Russia experience crises of gender identity of personality: the crisis of achieving consistency of gender identity, the crisis of self-actualization of gender identity, the crisis of external confirmation of gender identity9; according to research by S.B Kokhanova, these crises have been detected in 76% of girls and only in 30% of young men [14, p. 108].

In addition, the uncoordinated type of gender interaction is possible in matriarchal families. For example, this happens in a family, in which the woman is the main breadwinner. It is assumed that the man, who

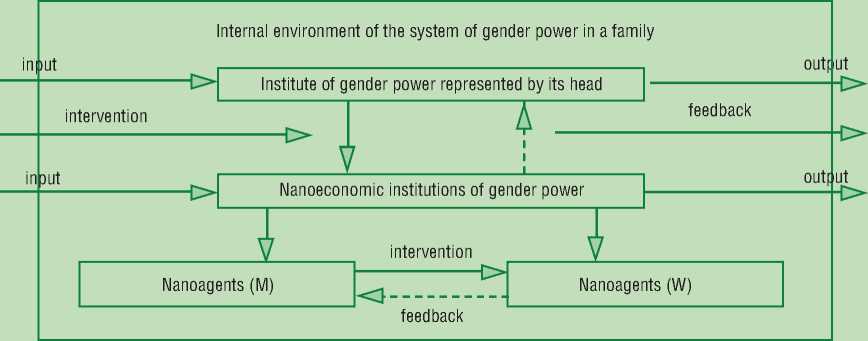

Figure 2. Family institutions of gender power as a multi-level synergistic system

External environment

is not so much employed in the labor market or not employed at all, should do certain housework in exchange for economic support from the woman. In fact, however, studies show that the more economically dependent a man is on his wife, the fewer amount of housework he does [7]. This pattern is most evident in families with low income. Accordingly, there is a clear mismatch in this type of family relationships.

In our opinion, the above transitional types of gender interactions correspond to the current conditions and the results achieved in the development of the institutions of gender power of liberal type, which, as we note in [3], are characterized by extensive network of subjects of gender power: men, social environment, organizations and the state. In this case the family acts as an open system with external factors (fig. 2). We point out that due to intensive (streaming) exchange between substance, energy, information and the environment in non-equilibrium conditions [10, p. 387], the system of gender power institutions, according to the second postulate of synergetics, could become a highly efficient synergistic system.

It turns out that the tendency towards disagreement in relations between spouses within a family is caused by incoherence of objectives of functioning of gender power institutions in the family and institutions of gender power at higher levels in the hierarchy: the power of social environment, organizations, power of the state and region (see more on the subject in: [3, 5]).

In such conditions it is much more difficult to achieve the balance, since the standards of behavior are destabilized, therefore, their sustainability is low, there is no consistency in their performance, transaction costs associated with their use are growing, coordination with other rules of behavior is difficult; certain agents appear, who want to change gender behavior stereotypes. Thus, stability, coordination, integration, learning and inertia, defined by V.M. Polterovich as the main mechanisms for institutionalization of codes of conduct [22, p. 73-76] are not complied with.

In addition, if we consider the impact of the socio-economic system on the system of gender power institutions, as we determined in [6], the levelling of concentration of gender power in family economy (which corresponds to the egalitarian type of coordinated interaction between spouses) is the most optimal at the modern stage of society development. Establishment of this type of balance is only possible in adequate institutional conditions; this fact confirms the necessity and willingness of economic agents to modernize the system of gender power institutions in Russia’s economy.

Cited works

-

1. Arutyunyan M.Yu. Gender Relations in the Family. Valdai-96: Proceedings of the First Russian Summer School on Studies of Women and Gender . Moscow: MTsGI, 1997. Pp. 132-133.

-

2. Bazueva E.V. The Human Capital of the Perm Region: Gender Peculiarities of Realization. Economy of the Region , 2010, no.2, pp. 46-59.

-

3. Bazueva E.V. Institutional Analysis of Gender in Contemporary Russia. The Economic Analysis: Theory and Practice , 2011, no.19, pp. 9-20.

-

4. Bazueva E.V. Gender-Related Specifics of Formation of Household Budgets in Perm Krai (on the Findings of a Longitudinal Study “Social and Market Economy of the Family”. Regional Economics: Theory and Practice , 2012, no.33, pp. 39-49.

-

5. Bazueva E.V. Institutional Environment in Modern Russia: Gender Criterion of Efficiency. Bulletin of Perm University. Series: Economics , 2011, no.2, pp. 48-60.

-

6. Bazueva E.V. Econometric Analysis of the Relationship between National Economic Indicators and Gender Inequality. The Moscow University Herald. Series 6: Economics , 2013, no.2, pp. 71-84.

-

7. Balabanova E.S. Housework as a Symbol of Gender and Power. Sociological Studies , 2005, no.6, pp. 109-120.

-

8. Bateneva T. Dad Can… Russian Newspaper “Business” , 2012, no.850, June 5.

-

9. Becker G. The Economic Approach to Human Behavior . Translated from English. Moscow: GU VShE, 2003.

-

10. Zakovorotnaya M.V. On the Philosophical Issues of Management of Social Systems: Status and Prospects. Synergetics and the Issues of Management Theory . Ed. by A.A. Kolesnikov. Moscow: FIZMATLIT, 2004. Pp. 465-482.

-

11. Zaev S.V. Elements of Contract of Relations in a Family: the Views of Young People. Personality as a Subject of Economic Life: the Gender Aspect. Gender Analysis of Economic Relations in Family, Career, Politics, Entertainment: Proceedings of the 5th All-Russia Research-to-Practice Seminar . Krasnodar: Kubanskii gos. un-t, 2005. Pp. 24-29.

-

12. Babysitting: Commercialization of Care. New Everyday Life in Contemporary Russia: Gender-Related Research into Everyday Life: Collective Monograph . Ed. by E. Zdravomyslova, A. Rotkirkh, A. Temkina. Saint Petersburg: Izd-vo Evropeiskogo universiteta v Sankt-Peterburge, 2009. Pp. 94-137.

-

13. Kirdina S.G. The X- and the Y-economies: Institutional Analysis . Moscow: Nauka, 2004. 256 p.

-

14. Kokhanova S.B. Empirical Description of Semantic Mechanisms of Gender Identity of Personality in Students Living in the City of Armavir. Topical Issues of Modern Genderology. Vol. 4: Proceedings of the 54th Annual Research-

and-Methodological Conference of Teachers and Students “University Science – to the Region” (April 16, 2009) . Moscow – Stavropol: Izd-vo SGU, 2009. Pp. 101-109.

-

15. Luk'yanov G.A., Roshchin S.Yu., Solntsev S.A., Travkin P.V., Uspenskii N.S. The Monitoring of the Labor Market of Top Managers in Russia (2000–2007): Preprint WP 15/2009/02 series WP 15 Scientific Works of the Laboratory for Labor Market Research . Moscow: Izd-vo GU VShE, 2009. 73 p.

-

16. Malysheva M.M. Modern Patriarchate. Socio-economic Essay . Moscow: Academia, 2001. 352 p.

-

17. Modernization of the Family: Attitudes of People in the 21st Century. Demoscope Weekly , 2011, no.475-476, August 29 – September 11. Available at: http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2011/0475/opros01.php (Accessed September 26, 2012).

-

18. North D. Understanding the Process of Economic Change . Translated from English by K. Martynov, N. Edel'man. Moscow: Izd. dom Gos. un-ta Vysshei shkoly ekonomiki, 2010. 256 p.

-

19. Ozhigova L.N. Psychology of Gender Identity of a Personality . Krasnodar: Kubanskii gos. un-t, 2006. 290 p.

-

20. Orlyanskii S.A. Transformation of Social Roles of Men (on the Materials of Sociological Research: Comparative Analysis). Topical Issues of Modern Genderology. Vol. 3: Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Research-and-Methodological Conference of Teachers and Students “University Science – to the Region” (April 16, 2008) . Moscow – Stavropol: Izd-vo SGU, 2008. Pp. 32-41.

-

21. Pospelova T.G. About the Methods of Gender-Related Analysis of Sociological Information). Topical Issues of Modern Genderology. Vol. 4: Proceedings of the 54th Annual Research-and-Methodological Conference of Teachers and Students “University Science – to the Region” (April 16, 2009) . Moscow – Stavropol: Izd-vo SGU, 2009. Pp. 47-49.

-

22. Polterovich V.M. Elements of the Theory of Reforms . Moscow: ZAO “Izdatel'stvo “Ekonomika”, 2007. 447 p.

-

23. Savinskaya O.B. Value of Employment and the Preferences in Working Conditions of Mothers of Preschool Children. Woman in Russian Society , 2011.

-

24. Sukharev O.S. Economy of the Future: the Theory of Institutional Change (New Evolutionary Approach) . Moscow: Finansy i statistika, 2011. 432 p.

-

25. Tambovtsev V.L. The Theories of Institutional Change: Textbook . Moscow: INFRA–M, 2009. 154 p.

-

26. Toffler A. The Third Wave . Moscow: AST, 1999. 784 p.

672 p.

Список литературы Transformation of gender power disposition in modern families as a driving force of institutional changes

- Arutyunyan M.Yu. Gendernye otnosheniya v sem'e . Valdai-96: materialy Pervoi rossiiskoi letnei shkoly po zhenskim i gendernym issledovaniyam . Moscow: MTsGI, 1997. Pp. 132-133.

- Bazueva E.V. Chelovecheskii kapital Permskogo kraya: gendernye osobennosti realizatsii . Ekonomika regiona , 2010, no.2, pp. 46-59.

- Bazueva E.V. Institutsional'nyi analiz sistemy gendernoi vlasti v sovremennoi Rossii . Ekonomicheskii analiz: teoriya i praktika , 2011, no.19, pp. 9-20.

- Bazueva E.V. Gendernye osobennosti formirovaniya byudzhetov domokhozyaistv v Permskom krae (po rezul'tatam longityudnogo issledovaniya “Sotsial'no-rynochnaya ekonomika sem'i”) . Regional'naya ekonomika: teoriya i praktika , 2012, no.33, pp. 39-49.

- Bazueva E.V. Institutsional'naya sreda sovremennoi Rossii: gendernyi kriterii effektivnosti . Vestnik Permskogo universiteta. Seriya: Ekonomika , 2011, no.2, pp. 48-60.

- Bazueva E.V. Ekonometricheskii analiz vzaimosvyazi pokazatelei natsional'noi ekonomiki i gendernogo neravenstva . Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta. Seriya 6: Ekonomika , 2013, no.2, pp. 71-84.

- Balabanova E.S. Domashnii trud kak simvol gendera i vlasti . Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya , 2005, no.6, pp. 109-120.

- Bateneva T. Papa mozhet.. . Rossiiskaya gazeta “Biznes” , 2012, no.850, June 5.

- Becker G. Chelovecheskoe povedenie: ekonomicheskii podkhod . Translated from English. Moscow: GU VShE, 2003. 672 p.

- Zakovorotnaya M.V. O filosofskikh problemakh upravleniya sotsial'nymi sistemami: sostoyanie voprosa i perspektivy . Sinergetika i problemy teorii upravleniya . Ed. by A.A. Kolesnikov. Moscow: FIZMATLIT, 2004. Pp. 465-482.

- Zaev S.V. Elementy kontrakta otnoshenii v semeinykh predstavleniyakh molodezhi . Lichnost' kak sub"ekt ekonomicheskogo bytiya: gendernyi aspekt. Gendernyi analiz ekonomicheskikh otnoshenii v sem'e, professional'noi deyatel'nosti, politike, sfere razvlechenii: mater. V Vseros. nauch.-prakt. Seminara . Krasnodar: Kubanskii gos. un-t, 2005. Pp. 24-29.

- Nyani: kommertsializatsiya zaboty . Novyi byt v sovremennoi Rossii: gendernye issledovaniya povsednevnosti: kollektivnaya monografiya . Ed. by E. Zdravomyslova, A. Rotkirkh, A. Temkina. Saint Petersburg: Izd-vo Evropeiskogo universiteta v Sankt-Peterburge, 2009. Pp. 94-137.

- Kirdina S.G. X-i Y-ekonomiki: Institutsional'nyi analiz . Moscow: Nauka, 2004. 256 p.

- Kokhanova S.B. Empiricheskoe opisanie smyslovykh mekhanizmov gendernoi identichnosti lichnosti studencheskoi molodezhi g. Armavira . Aktual'nye problemy sovremennoi genderologii.-Vyp. 4: materialy 54 ezhegodnoi nauchno-metodicheskoi konferentsii prepodavatelei i studentov “Universitetskaya nauka -region” (16 aprelya 2009 g.) [Topical Issues of Modern Genderology. Vol. 4: Proceedings of the 54th Annual Research-and-Methodological Conference of Teachers and Students “University Science -to the Region” (April 16, 2009). Moscow -Stavropol: Izd-vo SGU, 2009. Pp. 101-109.

- Luk'yanov G.A., Roshchin S.Yu., Solntsev S.A., Travkin P.V., Uspenskii N.S. Monitoring rynka truda top-menedzherov v Rossii (2000-2007 gg.): preprint WP 15/2009/02 seriya WP 15 Nauchnye trudy laboratorii issledovanii rynka truda . Moscow: Izd-vo GU VShE, 2009. 73 p.

- Malysheva M.M. Sovremennyi patriarkhat. Sotsial'no-ekonomicheskoe esse . Moscow: Academia, 2001. 352 p.

- Modernizatsiya sem'i: ustanovki lyudei-XXI . Demoskop-Weekly , 2011, no.475-476, August 29 -September 11. Available at: http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2011/0475/opros01.php (Accessed September 26, 2012).

- North D. Ponimanie protsessa ekonomicheskikh izmenenii . Translated from English by K. Martynov, N. Edel'man. Moscow: Izd. dom Gos. un-ta Vysshei shkoly ekonomiki, 2010. 256 p.

- Ozhigova L.N. Psikhologiya gendernoi identichnosti lichnosti . Krasnodar: Kubanskii gos. un-t, 2006. 290 p.

- Orlyanskii S.A. Transformatsiya sotsial'nykh rolei muzhchin (po materialam sotsiologicheskogo issledovaniya: sravnitel'nyi analiz) . Aktual'nye problemy sovremennoi genderologii. -Vyp. 3: materialy 53 ezhegodnoi nauchno-metodicheskoi konferentsii prepodavatelei i studentov “Universitetskaya nauka -regionu” (16 aprelya 2008 g.) . Moscow -Stavropol: Izd-vo SGU, 2008. Pp. 32-41.

- Pospelova T.G. O metodakh gendernogo analiza sotsiologicheskoi informatsii) . Aktual'nye problemy sovremennoi genderologii. -Vyp. 4: materialy 54 ezhegodnoi nauchno-metodicheskoi konferentsii prepodavatelei i studentov “Universitetskaya nauka -region” (16 aprelya 2009 g.) . Moscow -Stavropol: Izd-vo SGU, 2009. Pp. 47-49.

- Polterovich V.M. Elementy teorii reform . Moscow: ZAO “Izdatel'stvo “Ekonomika”, 2007. 447 p.

- Savinskaya O.B. Tsennost' zanyatosti i predpochteniya v usloviyakh truda materei doshkol'nikov . Zhenshchina v rossiiskom obshchestve , 2011.

- Sukharev O.S. Ekonomika budushchego: teoriya institutsional'nykh izmenenii (novyi evolyutsionnyi podkhod) . Moscow: Finansy i statistika, 2011. 432 p.

- Tambovtsev V.L. Teorii institutsional'nykh izmenenii: ucheb. Posobie . Moscow: INFRA-M, 2009. 154 p.

- Toffler A. Tret'ya volna . Moscow: AST, 1999. 784 p.