Transformation of social policy in Russia in the context of population ageing

Автор: Grigoreva Irina A., Ukhanova Yuliya V., Smoleva Elena O.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social development

Статья в выпуске: 5 (65) т.12, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Modern social policy in Russia is formed under the influence of population ageing. The paper presents our point of view on the current state of Russia's social policy. The relevance of the study is due to the fact that the demographic situation is undergoing inevitable changes and the role of the elderly in socio-economic life is becoming increasingly important. The goal of our work is to investigate the specifics of social policy in Russia in the context of population ageing. The novelty of the work consists in the fact that it dwells upon the capabilities of the social group “elderly” as a social resource. We mainly use the following research methods: analysis of laws and regulations at various levels, analysis of statistical and demographic data and results of sociological surveys conducted by VolRC RAS, and content analysis of website materials. The study was carried out both at the national and regional levels (on the example of the Vologda Oblast). We reveal trends in reorienting Russia's social policy toward a broader interpretation of ageing and application of the concept of active longevity. However, the values of active longevity indices in Russia are low in comparison with European countries. According to sociological surveys, the elderly population of the region, which includes citizens over 60 years of age, preserves the values of active life, and many today's pensioners do not think their state of health can interfere with their ability to work. We show how interaction between the state, civil society and citizens is developing in modern social policy. We reveal territorial unevenness in the development of the non-profit sector that addresses social problems of older citizens. In the end, we put forward proposals on updating social policy in the country in the context of population ageing.

Ageing, active longevity, employment, social services for the elderly, intersectoral interaction

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147224209

IDR: 147224209 | УДК: 316.346.32-053.9 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2019.5.65.8

Текст научной статьи Transformation of social policy in Russia in the context of population ageing

In recent decades, issues related to governing social processes have come to the fore in Russia in the context of profound socioeconomic, political and ideological transformations. In this regard, there is a need to reconsider current social policy. According to researchers, one of the priority directions to develop social policy in the Russian society is to shift from a social-democratic model characterized by an extensive system of social services for different population groups to the liberalization of the social sphere and provision of targeted forms of support to the poor.

Within the framework of an integrated approach, “social policy” is understood as an interaction between the state, business and civil society aimed to harmonize the interests of different social groups and regions for the purpose of achieving social peace [1]. Other authors also emphasize the work of various nongovernmental institutions in the field of health, education, social security and protection aimed to reconcile the interests of different social groups in the allocation of resources [2, 3, 4]. Thus, social policy should be viewed through the prism of resolving contradictions between the social interests of society as a whole and its individual groups and different regions. Second, the actors of modern social policy include not only the state, but also business and the civil society. We should point out that we observe a transition from the Soviet, paternalistic monopolistic state model to a three-sector (state, business and civil society) model proposed once by V. Korpi and developed in the famous book by G. Esping-Andersen [5].

The interaction between these actors is considered in the context of “intersectoral social partnership” as a constructive cooperation in addressing social issues in two or three sectors (government, business, nongovernmental sector (NGOs), beneficial to the population of the territories and each of the parties in connection with the pooling of resources [6, 7]. Proponents of various theoretical concepts (“publicprivate partnership” [8], “indirect public administration” [9], “co-production” [10]) agree that the participation of society as a partner of the government in the creation of social goods and services attracts additional resources to implement social policy and at the same time provides people with opportunities for personal fulfillment. However, it should be recognized that in practice the state and nongovernmental institutions (namely NGOs) often lack mutual trust and readiness for system-wide cooperation. The monopoly on resources creates unequal competition between state/municipal institutions and nonprofit organizations in the production of social services at the expense of budget funds.

The goal of our present work is to study general features of social policy in Russia in the context of population ageing. At this stage, the study is reduced to the consideration of the two most important actors in the designated area – the government and civil society structures (NGOs).

Research methodology

Social policy studies involve cross-country and intra-regional comparison as the main method of analysis. We use comparative legal and other variants of the comparative approach, since the empirical basis of the study includes secondary analysis of demographic and sociological data from various sources and the results of a survey conducted in the Vologda Oblast.

The information base of the research includes laws and regulations at various levels, statistical data of the Federal State Statistics Service, materials of the website of the Presidential Grants Fund, and profiles of non-profit organizations in social networks. In addition, we draw important information from sociological surveys conducted by Vologda Research Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences (hereinafter VolRC RAS). The representativeness of the sociological data obtained is ensured by using a model of multistage zoned sampling with quota selection of observation units. Sampling error does not exceed 3%. The assessment is conducted through surveys at the place of residence of respondents. Sample size is 1,500 people 18 years of age and older. The data is processed with the help of SPSS program.

Ageing: theories, facts, forecasts

Researchers mostly consider “population ageing” from the demographic perspective: as an increase in the number of elderly population [11], a shift in the age structure toward older age [12], and an increase in the average and median age [13; 14].

As we already noted, the fundamental cause of population ageing consists in the interaction of two centuries-old trends – increasing life expectancy (due to declining mortality) and declining birth rate. The contribution of declining birth rate and declining mortality to population ageing is not the same, nor are the possibilities for compensating for the negative effects that they may have.

In the course of 50 years – from 1950 to 2000 – the number of elderly people in the world has almost tripled (from 205 to 600 million people). If the views on the boundaries of old age do not change, then over the next 50 years it will again triple in 50 years and will amount to 2 billion people by 2050. The median age of the world’s population in the middle

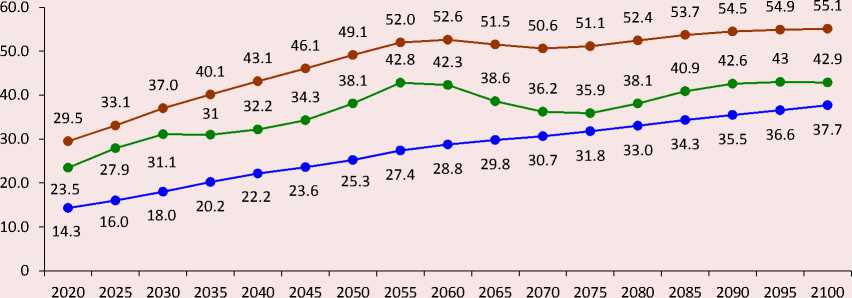

Figure 1. Forecast of changes in the old-age dependency ratio (ages 65 and older/ages 15 to 64)

е World • Europa • Russian Federation

Source: [World Population Prospects, 2019], medium-variant projection.

of the past century did not reach 24 years; in 2020 it will be 31 years, by 2050 it will rise to 36 years, and by the end of the century (2100) – to 42 years. In 1950, the median age for the Russian population almost coincided with the global data – 24.3 years. However, according to demographic forecasts, the ageing process in Russia will go faster: the median age will increase from 40 years in 2020 to 42 by 2050; in 2100 it will be 44.5 years1.

For Russia, the forecast of changes in the old-age dependency ratio – the ratio of older adults (ages 65 and older) to the working-age population (ages 15 to 64) – although it is more favorable in terms of the rate of ageing than for Europe, is ahead of the global rates (see Fig. 1 ).

However, it would be wrong to reduce population ageing studies to statistics and a demographic approach. Indeed, as we shall see, shifting the institutional boundaries of the old age can change the demographic picture created by dependency/support ratios. In modern statistics, the border between childhood and adulthood is in the range of 15–20 years, and the border between maturity and old age – 60– 65 years.

Priority shall be given to the age limits established by the pension legislation of each country. In accordance with the pension legislation, the data of Russian sociological studies indicated the boundaries of old age at 55 years for women and 60 years for men. At the same time, the implementation of active longevity concept can move the age limits of old age beyond 65 years. Both physicians and economists agree with this view: scales developed in the 1950s to interpret the population ageing coefficient (the most widespread of them are the J. Garnier – E. Rosset scale and the UN scale) need to be revised. Their calculations of the demographic ageing of the Russian population in the regional context according to the level, depth, drivers and rate of ageing show that only 60% of Russian Federation constituent entities have old and senile population. According to regional measurements on the UN scale, the population in 93% of RF entities belongs is in their old age [12, pp. 2208-2210].

To understand the boundaries of actual old age, it is necessary to combine information about the biological, psychological and social aspects of the ageing process. We will discuss sociological theories of ageing in detail and supplement them with data of psychological and economic concepts.

The first group of theories combines the attitude toward ageing as a process of separation and alienation. According to proponents of the theory of social disengagement, ageing process is characterized by a gap between the individual and society and by deterioration of the quality of social relations, which occurs due to the reduction of biological and psychological resources of an individual. Alienation occurs at a qualitative level through forced retirement, reduction of social activity, death of acquaintances of the same age, separation of children, etc. and this process is inevitable [15, p. 211]. Therefore, both the individual and society should get ready to deal with ageing (in other words, with alienation) so that the functioning of society remains stable. This approach is supported by those psychological concepts of ageing, in which the stage of life associated with old age is characterized by the loss of vital goals, pastime (Charlotte Buhler’s theory of intentionality), a desire for solitude, experience of losses, reduction of living space, an integrative assessment of the whole life lived (Erik Erikson’s epigenetic theory). This approach has been criticized for promoting a policy of indifference toward the problems of older people, since a person seeking privacy does not need to be integrated back into society.

The desire to separate the elderly from the rest of society is also reflected in the concepts of marginality, the subculture of old age, and in age stratification. According to proponents of these theories, old people are passive, marginal, socially and psychologically dependent; and the development of a network of social services provided to the elderly increases the tendency toward forming subcultural groups among them [16]. Therefore, a welfare state should develop special programs to support and fill the leisure time of older people, thereby supporting the feelings of insecurity and inferiority. The actions of society and the state in relation to the elderly are negative and preventive: prevention of diseases, mitigation of isolation, etc.

The second group of theories is based on the necessity and possibilities of preserving an active life position in the old age and promoting a significant social role of the elderly in society, responsibility for one’s own personality and physical and mental health. It is believed that the social activity of older people slows down the aging process and improves the quality of life [17; 18]. However, proponents of this theory spoke about the effects of stratification and alienating processes in relation to older people: “the need to integrate into society”, “to ignore age stereotypes”. Thus, it was indirectly confirmed that social activity in old age is an exception rather than the rule. Accordingly, social policy will be focused on creating opportunities for the elderly to be active in society. We have yet to investigate to what extent the concept of active and successful old age is implemented in modern Russian society.

The third trend in theoretical gerontology is represented by the concept of the continuity of normal ageing, which states that older people will usually maintain the same activity, behavior, relationships as in the early years of their life by adapting the strategies related to their past experiences [19].

A separate group of ageing concepts addresses the problems related to the allocation of resources and social services [14]. The elderly have limited access to most social resources, especially if their income is low. From the viewpoint of economic approaches to ageing, as R. Kapelyushnikov notes, the attention of researchers is focused mainly on the narrowly pragmatic aspects of this process (raising the retirement age, the deficit of the Russian Pension Fund, etc.). However, the demographic dependency (or support) ratios, which measure the economic burden placed on the working population, do not reflect these processes effectively. Scientists should focus not only on the demographic, but also on the economic dependency coefficients [14, p. 53]. Moreover, the elderly population is becoming not only more numerous, but also noticeably healthier: people begin to face serious diseases when they are much older and the number of diseases they face is reducing [20], thereby they maintain social and labor activity for a longer time.

It is important to emphasize that society needs confirmation that ageing is not a risk or a crisis, but a humanitarian victory. As for pessimism related to one’s own ageing and employment, most likely, shortens one’s life [21].

Social policy and active longevity

The “Strategy for actions in the interests of older citizens in the Russian Federation until 2025”2 should be called a conceptual document defining the renewal of the philosophy and practice of providing care and assistance to the elderly in Russia. The Strategy calls the elderly

“the older generation” without giving any usual remarks about their need and weakness; it increases the limit when the “older age” starts: 60 years for both women and men (in accordance with the Pension Reform, this limit will be raised to 65 years for men by 2028)3.

Thus, the strategic goals include reduction of age discrimination and elimination of gender discrimination; these goals, however, are not stated in the following documents. The older generation agenda was developed in the Decree of the President of Russia “On national goals and strategic objectives for the development of the Russian Federation for the period up to 2024”4 and, as a consequence, in the National Project “Demography”5. Two of the nine national development goals set out in Decree 204 for the period up to 2024 concern the quality of life of the older generation: (1) increasing life expectancy up to 78 years (by 2030 – up to 80 years); (2) ensuring sustainable growth of people’s real incomes and the level of pension provision above the level of inflation.

In addition to national development goals outlined in the President’s Decree 204, it is important to note a number of second-level targets set out in the national project “Demography” and directly reflecting the potential of active ageing: (1) the increase in healthy life expectancy (hereinafter HLE) to 67 years; (2) reducing mortality in the population older than working age to 361 persons per 10 thousand population of the corresponding age; (3) increasing the percentage of citizens who are regularly engaged in physical culture and sports, to 55.0%.

At the same time, it remains unclear whether these indicators can be achieved, since both healthy life expectancy and the reduction in the death rate are highly inertial processes. In conditions of instability in employment, low wages and low pensions, as well as ineffective medicine, it is futile to expect improvement in these indicators, although the official course of the Russian government is aimed at identifying additional opportunities for an active and full-fledged life after retirement.

Social policy is shifting toward a broader interpretation of ageing and a comprehensive assessment of its possible implications, embedded in the active ageing concept. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “active ageing” is the process of optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age6. Active longevity implies a fuller use of the potential of the elderly, especially in terms of skills (labor) and social participation.

In global research practice, one of the tools to identify the problems of ageing is the active ageing index (AAI, IAD), which measures the untapped potential of older people for active and healthy ageing across countries. [22]. It was revealed that Russia ranked 18th out of 28 EU countries (plus Russia) in 2010– 2012, i.e. it was in the middle of the rating, outstripping most Eastern European countries and some countries of Southern Europe. Since 2014, Russia is among the five bottom EU countries (plus Russia) in terms of AAI. When comparing the active ageing index for Russia and the EU, researchers conclude that one of the key problems of active ageing in Russia is low life expectancy and poor health, including psychological health. In addition, the negative sides of active ageing in Russia include low social activity and weak social ties [23].

In general, we should note that the decline in the value of AAI in Russia indicates a deterioration in the implementation of the potential for active longevity of older people; thus, it is necessary to fund new tools of social policy. At the same time, active longevity implies not only the development of social policy, but also the interested participation of the elderly in designing their life plans.

In this regard, we find it of interest to consider the values that are most important for the older population.

According to VolRC RAS sociological surveys, the main values that are preserved in old age include health, family well-being, high financial status, love, and personal well-being. However, the first two categories are valuable for a much larger number of people regardless of age, although the value of health increases with age (by 12 p.p. compared with the total sample; Tab. 1 ). In the senior elderly groups, the value of family well-being and high financial status decreases, but the importance of spirituality in life increases (by 5 p.p. compared to the total sample).

It should be emphasized that for people of pre-retirement and retirement age active life occupies a high enough place in the rating among the significant values (not lower than for the entire population of the region). However, the value of “being of service to people” is very low both in the elderly and in the general population, i.e. active life is focused on individual and family goals and values rather than on being of service to others.

Table 1. Values of Vologda Oblast population (% of respondents, N=1,500)

|

Indicators |

Aged 50–59 |

Aged over 60 |

Vologda Oblast population |

|||

|

% |

rating |

% |

rating |

% |

rating |

|

|

Health (physical and mental) |

75 |

1 |

76 |

1 |

63 |

1 |

|

Family well-being |

68 |

2 |

58 |

2 |

62 |

2 |

|

High financial status |

31 |

3 |

25 |

4 |

35 |

3 |

|

Love |

22 |

5 |

23 |

5 |

34 |

4 |

|

Personal well-being |

24 |

4 |

26 |

3 |

29 |

5 |

|

Good and loyal friends |

11 |

7=8 |

18 |

6 |

16 |

6 |

|

Active life (interesting and creative work, emotional richness of life) |

15 |

6 |

15 |

7 |

12 |

7 |

|

Self-confidence (inner harmony, freedom from internal contradictions, doubts) |

11 |

7=8 |

8 |

9 |

9 |

8 |

|

Spirituality |

10 |

9=10 |

13 |

8 |

8 |

9=10 |

|

High social status |

7 |

11 |

6 |

11=12 |

8 |

9=10 |

|

Being understood by others |

10 |

9=10 |

7 |

10 |

7 |

11 |

|

Independence, independence in judgments and actions |

6 |

12 |

6 |

11=12 |

6 |

12 |

|

Pleasant and easy pastime, no responsibilities |

3 |

13 |

5 |

13 |

3 |

13 |

|

Gratuitous service to people |

1 |

14 |

2 |

14 |

1 |

14 |

|

Source: VolRC RAS sociological survey, 2018. |

||||||

Demands of citizens in relation to the state are constantly growing. This is due both to the rhetoric of the Russian social state itself and to the information openness of modern Russia. In this situation, the population and social services invent positive and discriminatory characteristics that give them certain rights and remove questions concerning mutual obligations or personal responsibility of citizens of any social status.

However, an increasing role in the organization of society can be played by an outstanding personality who has their own view of the world and who is relatively independent of the state in economic terms. However, Russian social policy – the successor of the Soviet policy – does not take into account the existing new forms of social life [1]. In the new realities, the demands of man and society as a whole to the state in the production of social goods and services are changing: citizens are increasingly aware of themselves as taxpayers who finance the state so that it would meet their needs; and they see more and more clearly that the state is not a very conscientious executor of their requests [6].

Pension reform as a measure of modern social policy

Ageing and the increase in the number of the elderly are inextricably linked to the question of who and how will support them when they are no longer able or willing to work. And this question is acute not only in Russia, but also in the majority of successful welfare states [24]. In conditions of population ageing, sooner or later there emerges an urgent need either to raise the retirement age in order to increase the number of people employed in the economy, or to raise the rate of insurance premiums [25]. However, in Russia, a significant part of its economy is “in the shadow”, i.e. social contributions from shadow enterprises are not collected. In such a situation, it is useless to raise the rate of contributions, it is more important to take the enterprises “out of the shadow”. But to do this, it is necessary to increase trust in the government, which itself does not give grounds for this. Therefore, one of the most popular ways to adapt social policy to population ageing in most countries is to change the parameters of the pension system (namely, increasing the length of service or raising the retirement age).

When carrying out the pension reform, one should take into consideration the most urgent problems such as the health of the population of retirement age, as well as the provision of jobs for the older generation.

A number of researchers note that Russians have poor health and as they reach the retirement age, they are no longer able to work effectively [26; 27]. Other authors, conversely, argue that the real motive of the negative attitude of Russians toward raising the retirement age is not their poor health and fatigue, but the fact they lose the opportunity to receive “double payments” – pensions and wages simultaneously [28].

Survey data confirm the deterioration of subjective assessments of one’s own health in old age. If in the period from 50 to 59 years old every sixth inhabitant of the Vologda Oblast assesses their health as poor or very poor, then among people over 60 years of age this opinion is voiced by one in four Vologda Oblast residents (Tab. 2) .

Representatives of older age groups are more likely to talk about their diseases and ailments. But how much does this affect the ability to work, are there significant differences with the population of the region in this aspect?

Ailments in the form of injuries, headaches, general weakness, exacerbation of chronic diseases, all of which are rapidly cured under the influence of massage, medicines or without any treatment, are experienced monthly by 34% of elderly people aged 50 to 59 years (for comparison, data on the population of the region show 28%; Tab. 3 ). Every month 5% of the elderly in the group 50–59 years of age, like all the inhabitants of the region, fall ill and lose the ability to work at their place of employment, but can take care of themselves, do household chores, and cook meals. In older age groups, this figure increases to 14%. The findings show that more than half of the elderly can continue to work after they reach 60, and they go on sick leave once a year or less. In the “younger” age groups, this figure is even higher – 68%.

Thus, the state of health is not an obstacle for many of today’s pensioners to continue working. On the contrary, more and more studies confirm that retirement is harmful to health and a retired person can die at an earlier age [29; 30]. There is also a deterioration of cognitive functions in the elderly after they retire [31]; however, in Russia there are no comparable studies, there is too much confidence that ageing is equal to an incurable disease.

The second most important aspect in raising the retirement age is related to the relevance of the growth of economic activity of the elderly. The 2016 Strategy notes that, based on the

Table 2. Subjective assessment of their health status by the inhabitants of the Vologda Oblast (% of respondents, N=1,500)

|

Indicators |

50-59 |

Older than 60 |

Vologda Oblast population |

|

1. Very good |

6 |

5 |

7 |

|

2. Pretty good |

16 |

18 |

31 |

|

3. Satisfactory |

62 |

52 |

50 |

|

4. Poor |

15 |

24 |

12 |

|

5. Very poor |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

Source: VolRC RAS sociological survey, 2018. |

|||

Table 3. Subjective assessment of the severity and duration of diseases of the population of the Vologda Oblast (% of respondents, N=1,500)

|

Type of disease (disorder) |

50–59 |

Older than 60 |

Vologda Oblast population |

|

1. Ailments (headaches, general weakness, exacerbations of chronic diseases, injuries, wounds, etc.) quickly passing under the influence of massage, drugs or by themselves |

|||

|

– Almost every month |

34 |

44 |

28 |

|

– Several times a year |

36 |

31 |

33 |

|

– Once a year or less |

27 |

17 |

28 |

|

– Never |

7 |

9 |

11 |

|

2. Ailments that reduce the ability to work normally, but do not require a sick leave |

|||

|

– Almost every month |

23 |

28 |

16 |

|

– Several times a year |

41 |

38 |

32 |

|

– Once a year or less |

27 |

22 |

31 |

|

– Never |

9 |

12 |

21 |

|

3. Diseases that lead to the loss of the ability to work, study, etc., but do not deprive of the opportunity to engage in self-service, do household chores, cook, etc. |

|||

|

– Almost every month |

5 |

14 |

5 |

|

– Several times a year |

28 |

29 |

19 |

|

– Once a year or less |

42 |

30 |

34 |

|

– Never |

26 |

27 |

42 |

|

4. Diseases that confine to bed, leading to a complete loss of the ability to care for oneself; they require service from other people, treatment at hospital |

|||

|

– Almost every month |

3 |

2 |

2 |

|

– Several times a year |

8 |

14 |

5 |

|

– Once a year or less |

24 |

27 |

34 |

|

– Never |

65 |

55 |

42 |

|

Source: VolRC RAS sociological survey, 2018. |

|||

general trend of population ageing in Russia and the reduction of labor resources, the need of the economy to use the labor of older citizens will increase each year. At the same time, the problem of providing jobs for older citizens has not been fully resolved; this relates also to the fact that employers and society as a whole have negative stereotypes regarding the employment of the elderly.

In addition, we should take into account that raising the retirement age will not necessarily lead to an increase in employment. Those who want to work, continue to work regardless of any decisions the state may take in reforming the pension system. For example, according to a VolRC RAS survey, a quarter of respondents (25%) said that if it depended on them, they would continue to work upon reaching retirement age; the percentage of opposing responses was 39%; there was a large proportion of those who found it difficult to answer (36%; Tab. 4). It is noteworthy that almost 30% of respondents in the older age group (60 years and older) are ready to continue working.

At the same time, for people of preretirement age, the main motive to work in retirement is “the need for additional earnings” (84%), and the most urgent problem for current pensioners is “small pensions” (68%) [32]. But does it follow from the above that the relatively high level of employment among the elderly is often determined by economic motives, or is this the simplest and most familiar argument? Among working pensioners the share of those who has to work in connection with low level of pensions is high. But can we assume that work gives the elderly other meanings about which it is necessary to ask in more detail?

Table 4. Opinions of Vologda Oblast inhabitants on the continuation of employment after retirement (% of respondents, N=1,500)

|

Age groups |

Answer to the question “If it was up to you, would you stop or continue working after reaching retirement age?” |

||

|

I would continue working |

I would stop working |

Difficult to answer |

|

|

18…29 |

19.5 |

28.2 |

52.3 |

|

30…39 |

24.0 |

34.7 |

41.3 |

|

40…49 |

24.6 |

40.7 |

34.7 |

|

50…59 |

29.1 |

45.7 |

25.2 |

|

60 and older |

27.5 |

43.7 |

28.9 |

|

Oblast |

25.1 |

38.7 |

36.3 |

|

Source: VolRC RAS sociological survey, 2018. |

|||

When comparing the opinions of people who have already reached retirement age and those in their “pre-retirement” age, we can also note that “forced necessity” significantly straightens the motives for continuing employment. While people are not faced with the growing social exclusion of pensioners and have not found that they often have nothing to do, it seems that the main problem is a low pension. If children and grandchildren moved to big cities, it is especially traumatic. It turns out that “time is more than life”, especially if one does not have a habit of reading books and going to the library and does not have skills to use a computer or the Internet, which are always available in libraries. After all, older people used to work in one place, in one team; they get used to the fact that their friends are their colleagues and neighbors, etc. For the elderly, employment provided not only income, but also communication, friendship, mutual assistance.

Social services for the elderly

Retirement age alone does not mean that the person who has reached it has become elderly, and not only eligible for receiving a pension. In the world of socio-economic, rather than medical, indicators of ageing, the question remains, what exactly indicates that a person began to age: the refusal of employment or sexual life, a decrease in interest in others or indifference toward oneself? Many elderly people do not perceive taking care of themselves as an “investment that always pays off”7. Therefore, many elderly people, even women, cease to take care of themselves: they no longer take a shower regularly and dress neatly and tastefully, because they think that “I do not need it anymore”, “who can I be interesting to?”. Such untidiness and the “smell of old age” often cause rejection on the part of young people [33].

Legislation on social services linked the situation of the elderly, first of all, with their inability to get out of a “difficult life situation” on their own, with the absence of selfsufficiency and self-care. The focus on other needs and problems of the elderly was not made, although we can see that many of them (social exclusion, loneliness, poverty, etc.) may worsen the situation of an elderly person. At the same time, the ability/inability to take care of themselves has not been reflected in the system of evaluation indicators for the necessary service; it has remained a generalized characteristic of the entire population of the elderly. In relation to people 60 years of age recognition of any inability looks discriminatory. Even serving 80+ people needs to assess the extent of their loss of self-care ability.

It is also illegal to equate the ability to perform activities of daily living to the ability to provide for oneself, through the establishment of the age of the right to receive care the same as the right to receive a pension. Despite existing developments, indicators to assess the degree of loss of the ability to perform activities of daily living have not been adopted. It is important to emphasize that the necessity of perception of elderly clients of social services as buyers and consumers, as declared by Federal Law 442, changes the logic of social services8. On the one hand, the term “client” emphasized the status of the recipient as being dependent on state aid, his/her passive role in this process. The clients themselves saw only obligations towards them in social work, while the question of responsibility for their situation and for the assistance received was not even raised. The development of the services market, on the other hand, forces suppliers to impose certain services; despite the fact that they are included in the list of services, they are not always necessary for an experienced buyer and consumer.

The law also leads to the abandonment of state monopoly in the production and financing of services [34]. The “Strategy of actions in relation to...” indicates the growing need to involve the public in organizing various forms of care for elderly citizens. We agree with I.V. Mersiyanova and L.I. Yakobson, who point out that in practice the leadership of NPOs is observed in those sectors where external formal control is especially difficult and one has to rely on the conscience of people and their personal dedication [6]. This sector includes care for the elderly. Grant support or state subsidies are the most important tools for providing NPOs with resources on the part of the state in order to address social problems, including those related to pensioners. For this purpose, the concept of “socially-oriented NPOs”9 was introduced in the legislation; socially-oriented NPOs are considered as priority recipients of state subsidies and Presidential grants allocated to NPOs [35].

The content analysis of materials of the presidential grants website (which is a key source of funding for NPO social projects), has shown that according to the results of the second contest in 2018 in the area “Social service, social support and protection of citizens”, more than 580 million rubles were allocated in Russia, of which only 9% is directed to the projects for older citizens (Tab. 5) . Projects addressing the issues of the elderly and supported by the Fund, are represented to a greater extent in the Northwestern Federal District (15% of the total amount of approved projects); the number of such projects is the smallest in the Volga Federal District (5%); there are no such winning projects in the North Caucasian Federal District. Thus, we observe both the territorial unevenness of development of the NPO sector that addresses social problems of older citizens and the disproportion of support, when the share of the elderly in total population is 25%, and the share of supported projects for the elderly is only 9%.

According to the second contest conducted by the Presidential Grants Fund in 2018, the average amount of supported projects for the elderly was 1,309 rubles per thousand people over working age. The leader according to this indicator is the NWFD (4,092.9 rubles), the outsiders are the Volga and Southern federal

Table 5. State support provided by the Presidential Grants Fund to non-profit organizations in the direction “Social services, social support and protection of citizens” (winning projects in the second competition of 2018)

District Total number of projects (in rub.) Among them: the number of projects focused on the elderly (in rub.) Proportion of projects focused on the elderly in the amount of supported applications (%) Central Federal District 233 002 662,4 14 234 090,0 6,1 Northwestern Federal District 102 159 329,6 15 187 622,1 14,9 Southern Federal District 31 832 622,8 3 553 634,8 11,2 North Caucasian Federal District - - - Volga Federal District 95 353 512,3 4 354 432,0 4,6 Ural Federal District 38 433 204,5 4 768 252,7 12,4 Siberian Federal District 64 456 036,3 7 021 049,8 10,9 Far Eastern Federal District 17 375 063,3 1 838 330,0 10,6 RF 582 612 431,3 50 957 411,4 8,7 Source: Website of the Presidential Grants Fund. Available at: (accessed: 03.06.2019). Own calculation.

Figure 2. NPO projects that won the second 2018 contest of the Presidential Grants Fund for non-profit organizations in the direction “Social services, social support and protection of older citizens” (rubles per 1,000 persons over working age)

Source: Presidential Grants Fund website. Available at: (accessed 03.06.2019), own calculation.

districts (561.5 and 811.2 rubles, respectively; Fig. 2 ). It is obvious that social projects of NPOs, the target group of which are older people, are not developed sufficiently, despite their relevance and demand for them in Russia; their development requires joint efforts on the part of the state and the non-profit sector.

The analysis of the data on the winning projects of the Presidential Grants Fund and the analysis of official groups of non-profit organizations in the social media “VKontakte” have revealed the main activities of the nongovernmental sector in addressing the problems of the population of retirement age:

– organizing active leisure for senior citizens (cultural and recreational activities, amateur performances, tourism therapy – tourist and excursion activities);

– promoting a healthy lifestyle among the elderly (advice on proper nutrition, physical education and sports, recommendations of makeup artist, stylist and beautician);

– developing skills and knowledge in the field of information technology (computer skills and financial literacy), manual skills (sewing, dressmaking, weaving, knitting, etc.);

– maintaining the health and safety of the elderly (for example, fraud prevention);

– adaptation and socio-cultural rehabilitation of older persons who are in the care of social institutions.

Our study has revealed that most of the projects not only organize various forms of social and cultural activities for the elderly, but also involve volunteers from among people of the “silver age”, for example, to accompany the disabled, engage the elderly in social activities, participate in the socialization of orphans, etc. However, there has been no serious analysis of the results of “engaging older volunteers” yet.

Thus, the activities of NPOs and initiative groups are aimed both at organizing leisure and at creating conditions for employment and selfemployment of the older generation, promoting their social activity by engaging them in socially significant activities, forming a positive image of the pensioner as an active member of society. In this regard, it should be noted that, despite the fact that in Russia social projects of NPOs aimed at solving the problems of the elderly are not developed sufficiently, as evidenced, among other things, by low estimates of the population [36, pp. 29-38], it is important to point out a few successful practices of today. In modern Russian reality, it is necessary to promote further development of constructive interaction between the state and the public in the implementation of social policy in the context of population ageing.

Conclusion

It is extremely important to update social policy in the context of population ageing, because in this case we are talking about introducing the principle of self-responsibility and preservation of financial independence, self-reliance and the ability to perform daily self-care activities. In determining the prospects for the development of the country, the dynamics of the growth of the number of elderly people should be correlated with the state and trends of the labor market and employment rather than with a decrease in the birth rate. But the motivation of the elderly for delayed ageing is no less important than caring for them. For Russia, however, this approach is still a distant future. Paternalism and reliance on the government are preserved, because in today’s conditions there is no compensatory growth of small business, self-employment and non-governmental sector of social services.

In general, the pension reform, new forms of employment, predictive health care and rehabilitation medicine will provide a more definite answer to the questions about the need to increase the retirement age and the quality of life of the elderly in Russia. Active longevity involves not only efforts to improve health or quality of life, but also the active participation of older persons in building their own lives and promoting employment.

The attitudes of societies and the elderly themselves still retain the shade of the usual thesis that “pension is the time of rest”, when the quality of life of pensioners is the responsibility of the state, society and relatives, but not the elderly themselves. At the same time, studies show that today, a lot of people among those over 60 years old can be involved in socially significant activities, and whose health allows them to be active members of society, its “resource”. Studies have shown that pensioners in Russia have huge temporary resources, but this energy must be delicately directed in the right direction.

We see the following directions in updating social policy in the conditions of population ageing:

-

1. The state should provide more balanced coverage of Russia’s development prospects in the media. The dynamics of the growth in the number of the elderly should be correlated not only with the decline in the birth rate, but also with the state and trends of the labor market and employment.

-

2. It is necessary to use state television to motivate those who have reached retirement age to continue working, to increase employment with the help of incomplete, flexible, remote forms of self-employment, etc. The desire of older people themselves to “delay”

-

3. Instead of imposing sanctions for employers for dismissal of pre-pensioners and pensioners, the state should think about tax benefits for them in case of preservation of pensioners at their workplaces. There is also no need to persecute the informally employed and try to tax them. Any self-sufficiency of the elderly, of course, except criminal, must be supported.

-

4. It is necessary to explain to all age groups, starting with young people, that the quality of life is mostly the responsibility of the people themselves. Active longevity, in particular, involves not only efforts to improve health or quality of life, but also active participation of older persons themselves in building their life trajectories and preserving independence.

-

5. State monopoly on the production of social services should also be replaced by the active participation of business and NPOs in various forms of service with the participation of the elderly themselves as volunteers. If the elderly are not involved in solving at least their own problems and their places of residence, all the talks about them as a resource will be wasted, and the resource will not be used.

-

6. We need to develop various forms of cooperation between the elderly – with other organizations, church communities, various government agencies and authorities. This will help establish an active social field, revival in the field of alternative social work, and psychological revitalization of the elderly.

their ageing is no less important than the care of the state about them.

Список литературы Transformation of social policy in Russia in the context of population ageing

- Grigoryeva I.A. 100 years of social policy in Russia. Zhurnal issledovanii sotsial'noi politiki=Journal of Social Policy Research, 2017, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 497-514. 10.17323/727-0634-2017-15-4-497-514. (In Russian). DOI: 10.17323/727-0634-2017-15-4-497-514.(InRussian)

- Barker R. Slovar' sotsial'noi raboty [Social Work Dictionary]. Translated from English. Moscow: Institut sotsial'noi raboty, 1994. 645 p.

- Tikhonova N.E. Social policy in modern Russia: new systemic challenges Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost'=Social Sciences and Contemporary World, 2019, no. 2, pp. 5-18. 10.31857/S086904990004334-9. (In Russian). DOI: 10.31857/S086904990004334-9.(InRussian)

- Shkaratan O.I., Tikhonova N.E. Social policy: is there an alternative? In: Gosudarstvennaya sotsial'naya politika i strategiya vyzhivaniya domokhozyaistv [State Social Policy and a Strategy for Survival of Households]. Moscow: GU VShE, 2003. Pp. 443-461. (In Russian).

- Esping-Andersen G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton University Press. 1990. 260 p.

- Mersiyanova I.V., Yakobson L.I. The cooperation of the state with other structures of civic society for solving social problems. Voprosy gosudarstvennogo i munitsipal'nogo upravleniya=Public Administration Issues, 2011, no. 2, pp. 5-25. (In Russian).

- Yakimets V.N. Mezhsektornoe sotsial'noe partnerstvo (gosudarstvo - biznes - nekommercheskie organizatsii) [Intersectoral Social Partnership (State-Business-Non-Profit Organizations)]. Moscow: GUU, 2002. 80 p.

- Vasilenok N.A., Polishchuk L.I., Shagalov I.L. Obshchestvenno-gosudarstvennoe partnerstvo: teoriya i rossiiskie praktiki. Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost'=Social Sciences and Contemporary World, 2019, no. 2, pp. 35-42. 10.31857/S086904990004392-3. (In Russian).

- DOI: 10.31857/S086904990004392-3.(InRussian)

- Salamon L.M., Toepler S. Government-nonprofit cooperation: anomaly or necessity? Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 2015, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 2155-2177.

- Ostrom E., Parks R., Whitaker G. Patterns of Metropolitan Policing. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

- Zelikova Yu.A. Stareyushchaya Evropa: demografiya, politika, sotsiologiya [The Ageing Europe: Demography, Politics, Sociology]. Saint Petersburg: Norma, 2014. 224 p.

- Chereshnev V.A., Chistova E.V. Determination of regional aspects of population aging in Russia. Ekonomicheskii analiz: teoriya i praktika=Economic Analysis: Theory and Practice, 2017, vol. 16, no. 12, pp. 2206-2223. (In Russian).

- Ponomareva N.N. Demographic ageing: essence, features and implications in the countries of the world. Elektronnyi zhurnal "Vestnik Novosibirskogo gosudarstvennogo pedagogicheskogo universiteta"=Online Journal "Bulletin of Novosibirsk State Pedagogical University, 2013, no. 6 (16). (In Russian).

- Kapelyushnikov R. The phenomenon of population ageing: economic effects. Ekonomicheskaya politika=EconomicPpolicy, 2019, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 8-63. 10.18288/1994-5124-2019-2-8-63. (In Russian).

- DOI: 10.18288/1994-5124-2019-2-8-63.(InRussian)

- Cumming E., Henry W. Growing Old. New York: Basic Books, 1961. 293 p.

- Rose A.M. The subculture of the aging: a framework for research in social gerontology. In: Rose A.M., Robin S.S. (Eds.). Older People and Their Social Worlds. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company, 1965. Pp. 3-16.

- Havighurst R.J. Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 1961, vol. 1 (1), pp. 8-13.

- DOI: 10.1093/geront/1.1.8

- Lemon V.W., Bengtson V.L., Petersen J.A. An exploration of the activity theory of aging: activity types and life expectation among in-movers to a retirement community. Journal of Gerontology, 1972, vol. 27 (4), pp. 511-523.

- DOI: 10.1093/geronj/27.4.511

- Atchley R.C. A continuity theory of normal aging. The Gerontologist, 1989, vol. 29 (2), pp. 183-190. https://

- DOI: 10.1093/geront/29.2.183

- Eggleston K.N., Fuchs V.R. The new demographic transition: most gains in life expectancy now realized late in life. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2012, vol. 26, no 3, pp. 137-156.

- Grigor'eva I.A., Sizova I.L., Moskvina A.Yu. Social services for the elderly: implementation of Federal Law 442 and further prospects. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny=Public Opinion Monitoring: Economic and Social Changes, 2019, no. 4, pp. 125-144. Available at: https://doi. org/. (In Russian).

- DOI: 10.14515/monitoring.2019.4.09

- Zaidi A., Gasior K., Hofmarcher M., Lelkes O., Marin B., Rodrigrues R., Schmidt A., Vanhuysse P., Zolyomi E. Active Ageing Index 2012. Concept, Methodology and Final Results, Project: Active Ageing Index (AAI). European Centre Vienna, 2013. Available at: www.euro.centre.org/data/aai/1253897823_70974.pdf.

- Varlamova M.A., Ermolina A.A., Sinyavskaya O.V. Active Ageing Index as a tool for assessing the policy in relation to the elderly in Russia. In: Materialy sovmestnogo nauchno-prakticheskogo seminara "Aktivnoe dolgoletie v kontekste sotsial'noi politiki: problemy izmereniya", 2015 [Proceedings of the Joint Research-to-Practice Seminar "Active Ageing in the Context of Social Policy: Measurement Issues", 2015]. Available at: https://social.hse.ru/news/145390232.html (accessed: 05.02.2017). (In Russian).

- Velladics K., Henkens K., van Dalen H.P. Do different welfare states engender different policy preferences? Opinions on pension reforms in Eastern and Western Europe. Ageing and Society, 2006, vol. 26 (3), pp. 495-521.

- Barsukov V.N. To the question of raising retirement age in Russia. Problemy razvitiya territorii=Problems of Territory's Development, 2015, no. 5 (79), pp. 111-124. (In Russian).

- Aganbegyan A. About healthy life expectancy and pension age. EKO=ECO, 2015, no. 9, pp. 144-157. (In Russian).

- Vishnevskii A., Vasin S., Ramonov A. Retirement Age and Life Expectancy in the Russian Federation. Voprosy ekonomiki=Issues of Economics, 2012, no. 9, pp. 88-109. (In Russian).

- Gorlina Yu.M., Lyashok V.Yu., Malevoi T.M. Raising the retirement age: positive effects and probable risks. Ekonomicheskaya politika=Economic Policy, 2018, no. 1, pp. 148-178. (In Russian).

- Brockmann H., Muller R., Helmert U. Time to retire - time to die? A prospective cohort study of the effects of early retirement on long-term survival. Social Science & Medicine, 2009, vol. 69, pp. 160-164

- Bamia C., Trichopoulou A., Trichopoulos D. Age at retirement and mortality in a general population sample: the Greek EPIC study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 2008, vol. 167 (5), pp. 561-569.

- Eibich P. Understanding the effect of retirement on health using regression discontinuity design. SOEPpaper, 2014, no. 669. Available at:

- DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.2463240

- Ilyin V.A., Morev M.V. Pension reform and exacerbating issues of the legitimacy of the government. Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz=Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 2018, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 9-34. 10.15838/esc.2018.4.58.1. (In Russian).

- DOI: 10.15838/esc.2018.4.58.1.(InRussian)

- Rogozin D.M. What to do with the aging body? Zhurnal sotsiologii i sotsial'noi antropologii=Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology, 2018, no. 2, pp. 133-164. (In Russian).

- Klimova S.G. the Meanings and practices of denationalization of social services. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya=Sociological Studies, 2017, no. 2 (394), pp. 48-56. (In Russian).

- Ivashinenko N., Varyzgina A. Socially oriented NGOs and local communities in a Russian region: ways to build up their relationship. Laboratorium, 2017, vol. 3, pp. 82-103.

- Ukhanova Yu.V., Kosygina K.E. The non-profit sector in the estimates of the population of the region: socio-demographic aspect. Vestnik Voronezhskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Seriya: Ekonomika i Upravlenie=Bulletin of Voronezh State University. Series: Economics and Management, 2019, no. 2, pp. 29-38. (In Russian).

- Grigor'eva I.A., Sizova I.L. Trajectories of women ageing in contemporary Russia. Mir Rossii=The Universe of Russia, 2018, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 109-135. 10.17323/1811-038X-2018-27-2-109-135. (In Russian).

- DOI: 10.17323/1811-038X-2018-27-2-109-135.(InRussian)