Urban environment as a resource for combining professional and parental functions

Автор: Bagirova Anna P., Notman Olga V., Blednova Natalia D.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Social and economic development

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.14, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

In the context of approving the “quality of life” concept, the formation of accessible and comfortable living environment is mentioned in Russia's national projects and in Russian towns' development programs. The purpose of the study is to analyze the quality of urban environment in terms of infrastructure conditions, located within walking distance, that minimize physical, material, and time costs of parents' forced daily mobility for educating and developing children. The scientific novelty of the study is related to the first-implemented approach to considering urban environment of residential neighborhoods as a resource for combining professional and parental functions. The empirical basis includes data of a mass survey of citizens-parents conducted in the megalopolis (Yekaterinburg) and the results of in-depth interviews with mothers of preschool and school-age children. The results of the study show a high subjective significance of territorial proximity of key child infrastructure facilities for successful combination of parental and professional functions. Moreover, it indicates a direct interconnection between the saturation of residing places with children's infrastructure facilities and overall satisfaction of parents with the quality of urban environment. The authors record the highest forced mobility due to the lack of walking distance services in the field of intellectual, creative, and sports development of children. A total number of deprived urban neighborhoods and the share of parents who are forced to use infrastructure services outside their neighborhoods indicate that there are spatial inequalities in access to urban goods. Practical significance of the study is the scientific justification of the need to develop comprehensive programs for the formation of a functionally rich environment in microlocal territories during the adoption of a progressive model for the development of a megapolis - “a network of 15-minute cities”. The authors conclude that hyper-proximity-accessibility of urban services can be a significant resource (in a broader social policy for supporting families) for successful combination of parental and professional functions, ultimately contributing to improving the quality of life of citizens with children.

Urban environment, parental and professional functions, family-friendly policies, child infrastructure, forced mobility, neighborhoods, pedestrian accessibility, 15-minute city model

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147235411

IDR: 147235411 | УДК: 316.4 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2021.3.75.12

Текст научной статьи Urban environment as a resource for combining professional and parental functions

A person must perform various social roles daily in current highly dynamic society. Each one requires certain resource costs – time, energy, effort, etc. Supporters of the life and work balance concept distinguish two main areas where a person realizes his/her roles. The first one is associated with an individual’s professional activity, the second one – with everything outside it [1; 2]. This division is caused by the trend of active inclusion of women in the economy [3]. The resulting conflict (“workfamily conflict”) results from a lack of time to perform professional and family tasks, which can lead to an increase in a person’s stress, worsening of mental and physical health [4–6].

Some aspects of this problem have been studied by several Russian scientists. For example, I.E. Kala-bikhina and Zh.K. Shaikenova analyzed time transfers between members of Russian households, resulting in a conclusion about gender asymmetry and a greater contribution of women to the care economy [7]. V.D. Patrushev spent more than 30 years (1965–1998) studying the dynamics of time budgets in various categories of the population and the influence of income, social environment, work duration and intensity, education, and skill level factors on them [8]. Contemporary researchers, who record the trend of active combination of parental and professional functions (natural for, first, megapolises), explain it by the phenomenon of intensive motherhood, which implies compliance with the requirements of “advanced” parenting and selecting more diverse and better child services, despite the difficulties associated with this choice [9; 10]. According to O.G. Isupova, “intensive motherhood in the school period of children’s lives leads to constant mental stress and fatigue of mothers living in large towns of Russia” [11].

The increased need to address the issue of combining professional and parental functions has lead to several studies aimed at finding a balance between these two areas. Most often, scientists distinguish economic (payment of parental benefits) [12; 13] and organizational (provision of flexible working hours) [14; 15] measures to support working parents. However, working hours and poor financial incentives do not solve the problems faced by workers with children living in cities. A significant barrier to a successful combination of parental and professional functions is the conditions of the urban environment of life. The lack of children’s infrastructure in the vicinity of their residential places creates obstacles for parents, who are forced to spend more physical, material, and time resources on everyday transit to accompany children to educational, cultural, leisure, and sports institutions. Territorial remoteness of daily demand key infrastructure objects, burdened by traditional complex transport problems of Russian cities, leads to negative consequences for the psychological state and physical health of parents who are constantly forced to experience the stress of “falling out of schedule” of performing professional and family duties. However, this aspect – influence of urban conditions on the success/failure of combining parental and professional functions – has not yet been studied in empirical research on various aspects of the quality of life of urban residents.

The current focus of contemporary foreign and domestic urban studies is largely focused on the analysis of comfort, humanity, environmental friendliness, and anthropo-orientation of urban environment [16–18]. In the general framework of provisions of a convenient, livable city, research on “friendliness” of the urban environment for various categories of the population is being carried out – for example, people with limited mobility [19; 20], children and adolescents [21; 22], parents with young children [23; 24], and elderly people [25; 26]. It is worth noting that researchers are more focused on identifying various kinds of physical barriers to access to urban goods and amenities. For example, the lack of technical facilities for disabled people and parents with strollers, slippery surfaces, high stairs and curbs, lack of handrails, handrails, sound traffic lights, smooth surface of sidewalks, ramps, safe streets for pedestrians with speed limiters on the roads, wide-opening doors in everyday institutions., well-equipped public spaces are the main obstacles to active social life and barrier-free urban mobility of people with disabilities or parents burdened with children’s transit equipment. The hostility of the physical structure of urban environment for certain groups of citizens reinforces the practices of their social discrimination and spatial exclusion [19, p. 134], while the accessibility-barrier-free urban environment contributes to an increase in the level of living comfort and a variety of forms of social activity.

Currently, the importance of the concept of urban environment “comfort” is reflected in Russia’s national projects1 and in the largest Russian cities’ strategic development plans. At the same time, it is necessary to understand that the improvement of urban environment should not be limited to formal “decoration” (installation of benches, bins, lighting, landscaping of courtyards, etc.) masking more serious problems, such as unbalanced infrastructural development of urban areas, increasing differentiation of districts in terms of functional saturation, and the quality of local services, services. This problem has determined the focus of our research, which is focused on the analysis of environmental conditions in the microspace section – at the level of urban neighborhoods.

Urban environment is a multi-layered phenomenon that provides opportunities for multi-variant research interpretations and aspects of its analysis from the point of view of various urban sciences – architecture and urban planning, cognitive urbanism, ecology, geography, sociology, etc. The theoretical framework of our research is the socio-ecological (V.L. Glazychev) and socio-anthro-pocentric (T.M. Dridze) conceptualization of urban environment. V.L. Glazychev, noting the semantic duality of the “environment” concept, characterizes urban environment as the relationship of the subject-spatial environment, conditions and behavior, interaction of people in these subject-spatial conditions. Various combinations of the “city-body” subject framework, socio-anthropogenic and natural landscape determine the specific “pattern” of urban environment, while a harmonious balance between them determines its quality [27]. Considering the methodology of social cognition developed by T.M. Dridze, urban environment is studied through the prism of the interaction of natural, “man-made” (results of technical and technological civilization), information and symbolic (streams of signs and symbols transmitted to communication networks connecting people with each other), socio-psycho-anthropological (other people with their mentality, image, and lifestyle) factors that make up the human life environment [28, p. 134–135]. In our opinion, both interpretations embody an interdisciplinary urban approach that allows us to explore urban environment as a complex of interrelated conditions and artifacts – natural and artificial, material and immaterial.

Urban environment in the totality of its constituent elements appears as an environment for the realization of various human needs – in physical development, health preservation, housing, security, education, work, communication, cultural development, entertainment, recreation, etc. Practical possibilities for the implementation of a wide range of needs and practices characterize a certain quality of urban environment. In the logic of our research, urban environment is considered a space of everyday practices among families with children in the projection of the conditions provided by a city to minimize physical, material, and time costs of forced mobility. These costs, in our opinion, are the main barrier to achieving a balance between different spheres of life – especially between professional and parental ones.

We analyze the quality of environmental conditions not from the point of view of formal fullness of residential places with children’ s infrastructure facilities in accordance with regulatory needs of providing population with necessary services, but from the point of view of real practices of using urban goods near places of residence, as well as the satisfaction of citizens with various components of urban environment and the range of services provided. Look at urban environment from the perspective of its primary subjects –residents – allows us to identify how objective living conditions correspond to citizens’ real needs. Ultimately, a reliable assessment of the urban environment quality is determined not by the indicators of the commissioning of new infrastructure facilities, but by the “conversion” of achieved normative indicators into the quality of life and well-being of residents, considering their own perception and satisfaction.

The purpose of our research is to analyze the quality of urban environment of the Russian metropolis in terms of infrastructure conditions within walking distance, minimizing the physical, material, and time costs of forced daily mobility of parents for the education and development of children. The scientific novelty of the work is that we apply a new approach to studying urban environment (in the context of residential neighborhoods) as a resource for people to combine professional and parental functions.

Data and methods

In October–November 2020, we conducted an empirical study of the quality and accessibility of urban environment at the level of microlocal territories (micro-districts) in one of the largest Russian megacities – Yekaterinburg.

At the first stage of the study, a survey of Yekaterinburg residents was conducted. Respondents were recruited with a streaming sample using a set of websites that provide representation of a wide range of population (the city administration website; the leading information portal of the city е1.ru; virtual communities in social networks dedicated to Yekaterinburg; thematic groups of city activists, etc.). Then a calibration adjustment was made using frequency alignment procedures – poststratification based on gender, age, and residential area. From the final data set, 1,374 respondents were selected for analysis: parents with children of preschool and school age, 61.1% of which were women, and 38.9% – men. The median age of the parents surveyed was 34 years.

At this stage of the study, the following tasks were set that predetermined the logic of data analysis:

-

1) identification of overall satisfaction with the quality of urban environment in a place of residence (vital components of urban environment, social, consumer, recreational, child, transport infrastructure, aesthetics of urban environment);

-

2) assessment of scarce goods/services of pedestrian accessibility;

-

3) determination of forced mobility of parents associated with insufficient equipment of residential neighborhoods with child infrastructure facilities (schools, kindergartens, clubs and development centers, sports clubs);

-

4) identification of deprived neighborhoods based on the saturation of child infrastructure facilities;

-

5) assessment of the impact of the equipment of micro-districts with child infrastructure facilities on the overall satisfaction with the quality of urban environment.

Data processing and analysis were performed in SPSS 23.0. Statistical procedures were used for descriptive statistics, frequency analysis, and evaluation of the statistical significance of differences using the Mann–Whitney test.

At the second stage of the study, in-depth interviews with working mothers, aged 18–45 years (N = 9), were conducted. Mothers with children of junior, middle, senior preschool, and primary school age were selected, since this age interval corresponds to the most intensive stage of parental work. The interview guide included three main topics for discussion: professional and parental responsibilities of a respondent (types of activities, organization of work, intensity of work, etc.); barriers that prevent optimal combination of two employment types; necessary measures to support workers with children. When analyzing the results, special attention was paid to identifying subjective significance of the territorial proximity of child institutions and infrastructure facilities for working mothers, as well as their perception of environmental conditions as a support resource that helps to smooth out the family-work conflict and effectively combine parental and professional functions.

Results

Table 1 shows parents’ overall assessment of urban environment of residential neighborhoods.

Table 2 shows the opinions of parents about the lack of walking distance infrastructure in the residential district.

Thus, it is the objects of child infrastructure that were the most scarce in terms of walking distance. The share of parents who noted the lack of infrastructure in the territorial proximity (walking distance) for the intellectual, physical, and cultural development of children is about 40%. In the

Table 1. Satisfaction of Yekaterinburg residents, who have preschool and school-age children, with the quality of urban environment*

|

Indicator |

Urban environment elements |

Average |

Standard deviation |

Median |

Mode |

|

I. Vital components of urban environment |

|||||

|

1 |

Environmental situation |

3.20 |

1.181 |

3 |

4 |

|

2 |

Safety of living |

3.38 |

1.092 |

4 |

4 |

|

II. Social and household infrastructure |

|||||

|

3 |

Housing and utility services (uninterrupted supply of energy resources, hot and cold water, major repairs of houses, garbage collection, etc.) |

3.44 |

1.141 |

4 |

4 |

|

4 |

Availability of household services (dry cleaning, repair shops, etc.) |

3.68 |

1.180 |

4 |

4 |

|

5 |

Medical services (quality of work of polyclinics, level of medical care) |

3.03 |

1.146 |

3 |

3 |

|

III. Consumer infrastructure |

|||||

|

6 |

Markets and shopping centers |

3.68 |

1.317 |

4 |

5 |

|

7 |

Public catering establishments (cafes, restaurants) |

3.28 |

1.305 |

3 |

4 |

|

IV. Recreational infrastructure |

|||||

|

8 |

Entertainment industry (cinemas, bowling alleys, clubs, etc.) |

2.88 |

1.413 |

3 |

1 |

|

9 |

Parks, green areas, recreation areas |

3.70 |

1.246 |

4 |

5 |

|

V. Child infrastructure |

|||||

|

10 |

Sports services of open street access (stadiums, playgrounds, ice rinks) |

3.41 |

1.309 |

4 |

4 |

|

11 |

Cultural and leisure centers for children (clubs, sections, development centers) |

3.30 |

1.208 |

3 |

4 |

|

VI. Transport infrastructure |

|||||

|

12 |

Transport accessibility (developed transport network, convenience of routes, speed of movement to the city center) |

3.67 |

1.262 |

4 |

5 |

|

13 |

Parking quality |

2.52 |

1.163 |

2 |

2 |

|

VII. Aesthetics of urban environment |

|||||

|

14 |

Improvement of the neighborhood (street lighting, playgrounds, pedestrian zones, public spaces, etc.) |

3.18 |

1.235 |

3 |

3 |

|

15 |

Appearance of a neighborhood (streets, roads, houses) |

3.21 |

1.150 |

3 |

3 |

|

Overall satisfaction |

3.30 |

0.750 |

3.33 |

3.27 |

|

|

* A quantitative scale from 1 to 5 was used for the measurement. Source: own compilation. |

|||||

Table 2. Scarce walking distance urban infrastructure according to parents

On the contrary, those informants who had a kindergarten and a school within walking distance estimate this fact as a significant advantage: “Now, we have a kindergarten near the house, although at first we got a place in the Chapaev district that is far from us. I had to drive, and there was just a terrible road because of dirt and hour-long traffic jams on our way back. We went there for a week and gave up. Then the child stayed at home for nearly a year. We were waiting for a place in a kindergarten near the house. It is a different story now. Our older child really wants to take the younger one in the kindergarten and back, but he won’t be allowed, because only an adult can do it. We have a school across the house, so it is also very convenient that the child goes everywhere on his own. In the first grade, I probably met him for two weeks, and then he began to return home on his own. I cannot imagine how parents who need to go to kindergarten and school live... Here is an Akademichesky, for example, a huge district was rebuilt, a lot of people moved there to live, and there is a noticeably big problem with kindergartens.... And when there is a territorial link to the kindergarten, this is a great advantage” (Yulia, 35, has children aged 6 and 9 years).

For some working women, the absence of a municipal kindergarten near the house or inability to get into it (or a private kindergarten with acceptable conditions) was the reason for the decision to suspend their careers or find another job: “At first, I worked as a mining engineer for a private company, but then I had to quit. My daughter went to kindergarten, and it was far away, so I had to make a choice – either to leave or look for a private kindergarten. As a result, I still had a strained relationship with my employer at that job, and I had to constantly ask for time off. So, I left. Then I stayed at home for a while, looking for a job, so that I could spend time with my family” (Olga, 35, has children aged 7 and 9 years); “ In general, before this job, it turns out, I worked in a bank – the Ural Bank for Reconstruction and Development. I had a working week from 8 to 19:30, there was only one day of during a week and Sunday. And when Sofia went to the garden, and Liza went to the preparatory courses before the first grade, it was necessary to carry both . Either my husband and I leave together in the morning, take the youngest girl to the garden, or someone alone takes everyone back in the evening. Lisa’s grandmother goes with her by bus when she has time. The problem is to connect everything when everyone is in different places. And we only have one car. So, I could not stand it, I quit and went to this job as a sales representative, so at any moment I could go away, pick up the child, take her to the pool, to the hospital, somewhere else, or stay at home with her…” (Marina, 35, has children aged 4 and 9 years).

To make up for the lack of time and reduce the level of stress, working parents often must resort to the help of grandparents who could accompany a child to a kindergarten or school. Thus, mothers who are actively engaged in a professional career note that “due to the workload, it was simply impossible to do without the help of my grandmother. Since we did not have a kindergarten and school near the house or on the way to work, duties of drivingbringing the child were completely assigned to my mother. So, when we went to school, my grandmother, although she was not planning it, left work to help us. When our grandmother leaves, the life turns into constant traveling around the city and traffic jams – to school, to dance, to English. It is terribly exhausting, and I do not have any strength in the evening” (Anna, 45, has a 9-year-old daughter and a 21-year-old son who lives separately).

The lack of help from older family members is compensated by the search for alternative models of accompanying children: “When my son was little, I took him to a kindergarten, and father took him back. I do not take him to school now. His classmate’s mother drives him there. That is, we all live close to each other, so she takes him with her son. Well... she can do it; she brings them in and takes them back. It turned out that they began to travel with her constantly in that year. And for me, an extra hour or two is a time when you can do a lot of things” (Vika, 34, has a 10-year-old son).

In general, the location of child infrastructure facilities in Yekaterinburg often coincides with the place of residence of families with children. Depending on the type of infrastructure, the share of parents who noted that infrastructure facilities are in the residential district ranges from 56.9% (sports clubs) to 78.6% (kindergartens). Of all surveyed Yekaterinburg residents who have children of preschool and school age, 21.4% take their children to kindergartens, 23.4% – to schools, 33.1% – to clubs and development centers, 43.1% – to sports clubs located in other micro-districts (Tab. 3).

The results of the interviews show that the territorial “binding” of non-main objects of child infrastructure (clubs, development centers, sports sections) is also important for parents. When choosing additional types of education and development of their children, working parents, in conditions of time scarcity, focus primarily on territorial proximity, which allows children from a certain age to get to the necessary institutions independently: “ My son goes to karate and English courses. It is all in the next house. Where he can go himself, he goes there ” (Olga, 35, has children aged 7 and 10 years); “ Older child goes to a music school on his own because it is nearby . In the first year, in the first grade, we took him there, and, from the second grade, he goes there on himself, it is not far away, and we talked about the route in detail. Well, the advantage is that we live near the Shartash market, there are no large streets there, basically you need to go through the yards, so he goes alone . He also visits a development school, robotics, and chess. This is also literally two yards away, and he walks on his own” (Yulia, 35, has children aged 6 and 9 years). This strategy – “we choose what is nearby” – is a rational mechanism for minimizing parental transit costs, but, in this case, it is not always possible to ensure that a child’s abilities, needs, and desires correspond to the institutions available nearby.

During the study, we recorded a list of microdistricts, families with children from which are forced to demonstrate the highest level of intra-city mobility, moving to places of child infrastructure

Table 3. Location of urban infrastructure for children’s development, % of parents who responded

|

Coincidence of the residential neighborhood with the neighborhood of the location of a child infrastructure object |

Child infrastructure facilities |

|||

|

Kindergarten |

School |

Clubs, development centers |

Sports sections |

|

|

Coincide |

78.6 |

76.6 |

66.9 |

56.9 |

|

Does not coincide |

21.4 |

23.4 |

33.1 |

43.1 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Source: own compilation. |

||||

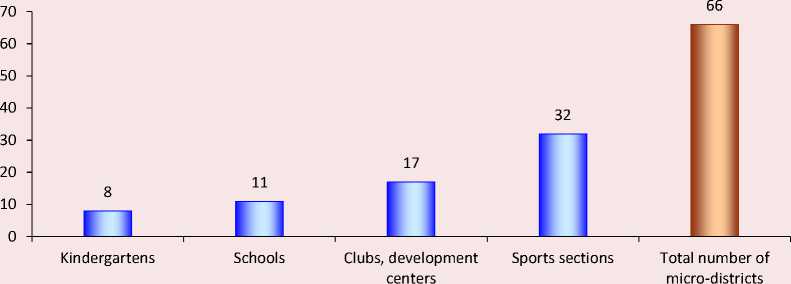

Figure 1. Number of micro-districts in Yekaterinburg where families with children who are deprived of territorial proximity of child infrastructure facilities live

Source: own compilation.

and back. Figure 1 shows a number of microdistricts where families with children are deprived according to each of the analyzed parameters.

Out of the total number of micro-districts in Yekaterinburg, three urban micro-districts were simultaneously deprived of all four categories of objects (Shirokaya Rechka, Sovkhozny, Yuzhny), of three objects – 6 micro-districts (Vokzalny, Shinny, Sinie Kamny, Shartash, Parkovy, Keramika), of three objects – 11 micro-regions (Akademichesky, Michurinsky, Zarechny, Izoplit, Istok, Elizavet, RTI, Shuvakish, Uktus, Novaya Sortirovka, Kalinovsky), of one object – 15 microregions (Polevodstvo, Ptitsefabrika, Avtovokzal, Vtorchemet, Botanichesky, Koltsovo, Lechebny, Medny, Nizhne-Isetskiy, Pionersky, Sortirovka, Tsentralny, Shartash Market, Elmash, Yugo-Zapadny). It should be noted that informants from infrastructurally “deprived” areas reacted most passionately and emotionally to questions about the importance of territorial proximity of child institutions: “We bought an apartment in a remote area in Shirokaya Rechka. There are no kindergartens at all. They gave us a kindergarten far away from home. There is only one kindergarten here. And we did not get there, of course. Apparently, there is a very large queue. Again, we asked, we are two education workers, give us a closer kindergarten through some connections. But it did not work out. Even the money did not help. I had to travel far. And only a year later they gave us a closer kindergarten. But it is still necessary to go by a car. This is not a walking distance., We asked in an appeal why are so few kindergartens planned for construction in our district? Roughly speaking, the answer was: “No one asked you to buy an apartment so far away”. Well, that is, you bought it yourself and now live there. What parks, what kindergartens? This is Shirokaya Rechka... No one wants us here” (Ekaterina, 29, has a 5-year-old child); “I went through all of this with my daughter. Heavily. We had no school nearby, no kindergarten. We bought an apartment in a young residential area, in a nice house, but without everything. There is absolutely nothing nearby. I always must think of something, ask someone. I remember when my friend picked up my child from school and brought him to her home during frosts, because I was working and could not come. I need support from the authorities. Well, why don’t you build a school or a kindergarten in our district? At least I go to the hospital for free. Thank you for that at least” (Ol’ga, 33, has children aged 2 and 8 years).

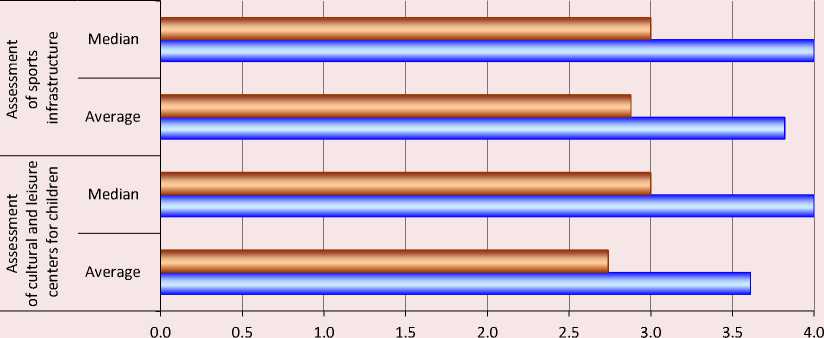

The coincidence of the residential neighborhood and the location of child infrastructure facilities is shown in the overall assessment of the quality of life of the respondents-parents in the neighborhood. Figure 2 shows significant statistical differences supporting this statement (Mann–Whitney test, p =0.000).

Consequently, the assessment of cultural and leisure centers for children in respondents’ residential districts is higher when they take their children to clubs and development centers located in their own neighborhood. Similarly, the assessment of the infrastructure for child sports in respondents’ residential district is higher when they take their children to sports clubs located in their own neighborhood.

The presence of infrastructure for children in the residential area of respondents is associated with the assessment of the neighborhood according to several parameters – and not only on those aspects that seem to relate directly to children. For example, respondents-parents, whose kindergarten is not located in the residential district, evaluate their neighborhood worse than parents who live in the residential district with a kindergarten, only by one parameter. If the residential district does not coincide with the residential district with a school, then it is assessed lower by 8 parameters. Due to the lack of a sports section, where the respondents-parents take their children, the neighborhood receives lower ratings according to 11 parameters, and due to the lack of clubs and development centers – according to 15 parameters. In table 4, the orange color indicates the parameters for which neighborhoods received lower ratings if they did not have certain elements of child infrastructure.

Discussion

Our research is a kind of “pioneer” in terms of the choice of research focus (analysis of urban environment as a condition for successful combination of parental and professional functions) and the developed methodology for assessing spatial differences in the saturation of urban

Figure 2. Assessments of individual parameters of residential neighborhoods by respondents-parents (groups of respondents identified by the principle of the location of a child infrastructure object in/outside the residential area)

□ The object is outside the residential micro-district □ The object is in the residential micro-district

Source: own compilation.

Table 4. Results of the comparative analysis of the urban environment quality in case of the location of child infrastructure facilities outside the residential area

|

Indicator |

Urban environment elements |

A lower rating given by the respondents-parents, provided that it is necessary to use a child infrastructure object outside the residential district |

|||

|

Kindergarten |

School |

Clubs, development center |

Sports section |

||

|

I. Vital components of urban environment |

|||||

|

1 |

Environmental situation |

||||

|

2 |

Safety of living |

||||

|

II. Social and household infrastructure |

|||||

|

3 |

Housing and utility services (uninterrupted supply of energy resources, hot and cold water, major repairs of houses, garbage collection, etc.) |

||||

|

4 |

Availability of household services (dry cleaning, repair shops, etc.) |

||||

|

5 |

Medical services (quality of work of polyclinics, level of medical care) |

||||

|

III. Consumer infrastructure |

|||||

|

6 |

Markets and shopping centers |

||||

|

7 |

Public catering establishments (cafes, restaurants) |

||||

|

IV. Recreational infrastructure |

|||||

|

8 |

Entertainment industry (cinemas, bowling alleys, clubs, etc.) |

||||

|

9 |

Parks, green areas, recreation areas |

||||

|

V. Child infrastructure |

|||||

|

10 |

Sports services of open street access (stadiums, playgrounds, ice rinks) |

||||

|

11 |

Cultural and leisure centers for children (clubs, sections, development centers) |

||||

|

VI. Transport infrastructure |

|||||

|

12 |

Transport accessibility (developed transport network, convenience of routes, speed of movement to the city center) |

||||

|

13 |

Parking quality |

||||

|

VII. Aesthetics of urban environment |

|||||

|

14 |

Improvement of the neighborhood (street lighting, playgrounds, pedestrian zones, public spaces, etc.) |

||||

|

15 |

Appearance of a neighborhood (streets, roads, houses) |

||||

|

Overall satisfaction |

|||||

|

Source: own compilation. |

|||||

neighborhoods with child infrastructure objects and their pedestrian accessibility (using sociological, rather than statistical methods). Despite the fact that the amount of works devoted to the quality of urban environment has been steadily growing in the last decade, there are currently no similar studies in the scientific literature focusing on the impact of accessibility of urban environment on achieving a balance of various spheres of life (in particular, family and professional), performed with a high level of spatial detail (in the micro-space section) and the use of sociological tools for comprehensive coverage of all inner-city territories (residential neighborhoods) without exception.

The results of the study show that the overall satisfaction of urban parents with child infrastructure facilities does not significantly differ from the satisfaction with other elements of urban environment. However, the share of parents experiencing a shortage of child infrastructure facilities within walking distance from their places of residence significantly exceeds the share of those who name other urban services scarce. Even though the objects of child infrastructure are mainly located in the residential district, this coincidence cannot be considered “ideal” in terms of the infrastructure saturation of the residential places. First, many Yekaterinburg micro-districts have a territorial extent that exceeds the radius of comfortable pedestrian accessibility, which does not allow considering the location of objects within formal boundaries of a micro-district as the only criterion for environmental well-being. In addition, the results of in-depth interviews with mothers indicate that pedestrian inaccessibility of key child infrastructure objects is a relevant problem for successful combination of parental and professional responsibilities, since it significantly complicates daily logistics and does not contribute to saving time, rational distribution of energy and effort.

Second, the share of parents who are forced to use child infrastructure facilities outside of their residential neighborhoods is still remarkably high – from 21 to 43%. At the same time, the highest forced mobility is recorded in the sphere of meeting the needs of intellectual, creative, and sports development of children.

Out of 66 urban micro-districts, many of them (35) are considered deprived according to various criteria, and, among them, there are not only residential new buildings or areas that are geographically remote from the core of cultural and educational life of the city, but also territories that are central and close to the center. Special attention from the authorities, in our opinion, should be paid to the infrastructural development of microdistricts that are, at the same time, disadvantaged by several criteria. In them, families with children find themselves in the worst environmental conditions, forcing them either to make exorbitant efforts to meet the development needs of their children, or to refuse non-basic (but significant for children) developmental services.

A significant result of our study is the fact that there is a direct relationship between parents’ assessments of the availability of child infrastructure in a nearby vicinity of their residential places and overall satisfaction with the quality of urban life. A high subjective significance of the territorial proximity of child infrastructure objects for parents in the overall picture of the perception of the comfort of urban environment reflects the specific lifestyle and needs of the studied group of citizens, which must be considered when developing strategies for the development of urban neighborhoods.

The emergence of spatial inequalities associated with restrictions on access to urban goods and infrastructure, differentiation of the quality and functional saturation of urban environment, and transport deprivation in several districts is today one of the most significant problems, the solution of which requires the development of comprehensive programs for the formation of a functionally saturated environment at the level of microlocal territories. The processes of urban sprawl, combined with the unresolved transport problems in megapolises, lead to the isolation of certain urban areas, whose residents are “disconnected” from the social infrastructure and the benefits of urban life. They must make intra-city trips several times a day, often overcoming all sorts of environmental barriers, including unfavorable urban traffic conditions.

In the light of the identified problems, the models of urban development that allow leveling the intra-city territorial imbalances of the living environment become particularly relevant. One of the progressive models that integrates a set of guidelines for sustainable urban development (compactness, polycentrism, environmental friendliness, anthropo-orientation) is the “15-minute city model”, proposed by the Franco-Colombian researcher C. Moreno [29]. It is based on the idea of decentralizing urban life. The city of quarter hour is a mosaic of urban neighborhoods, within which all the key urban functions are concentrated –housing, work, retail, medical services, education, culture, leisure, recreation. The theoretical basis of the 15-minute model is the concept of “chrono-urbanism”, which considers the quality of urban life as a “quantity” inversely proportional to the amount of time spent on everyday transit [30]. Hyper-proximity is the availability of key services/amenities and its corresponding micro-mobility contribute to the achievement of a set of positive effects, such as reduced dependence on cars (saving environmental resources), saving time and financial costs for transit (reallocation of time and costs for other activities – leisure, recreation, family, and parental responsibilities), improvement of the local quality of life (diversity in all its manifestations at the level of inner-city areas), “reunion” of residents with their local areas, and formation of a local identity (strengthening of the social “fabric” of urban life).

We believe that the 15-minute city model is not “rigid”, so it can be adapted to the specific features of specific cities, their scale, morphology, characteristics of inner-city territories, and the needs of residents. The latter seems particularly important to us since the need to consider the needs and opinions of residents is becoming increasingly obvious because of widely discussed issues of citizens’ involvement in the processes of designing urban changes [31]. The involvement of residents in the evaluation and selection of projects to be implemented on their own territory, as shown by the experience of progressive foreign megapolises

(for example, Paris, Ottawa, Melbourne2), which have already begun to implement the “hyperproximity-accessibility” model, plays an important role in achieving the goals of creating a high-quality and affordable urban environment, the formation of sustainable and socially interconnected communities, and, ultimately, the birth of healthier cities in the ecological, economic, and social aspects.

Conclusion

As a result of our study on the accessibility of urban environment for families with children in the territorial-local projection, we reveal, on the one hand, the problems of infrastructural imbalance in the development of urban neighborhoods of a particular metropolis – Yekaterinburg – which prevent the effective combination of parental and professional functions. On the other hand, the authors focus on the fact that the implementation of the priority federal project “Creating a comfortable urban environment” requires not only small tactical decisions on the improvement and “beautification” of urban spaces, but also the development of longterm strategic approaches to the development of Russian cities. Strategic objectives for the formation of a high-quality, functionally rich environment at the level of urban micro-territories actualize the issues of “upgrading” the existing infrastructure conditions in accordance with the needs of residents. In this context, the results obtained are of high practical significance since they can be used to make informed management decisions to prevent a sharp polarization in the development of urban areas. Based on the conducted research, we conclude that a functionally rich, pedestrian-accessible urban environment that minimizes the forced “costly” mobility of families for the purposes of education, development, and leisure of children (they increase in the megalopolis due to the phenomenon of intensive motherhood described by sociologists) can act as a significant resource (along with economic and corporate measures to support families – family-friendly policies) for the successful combination of parental and professional functions, ultimately contributing to improving the quality of life and subjective well-being of citizens with children.

Список литературы Urban environment as a resource for combining professional and parental functions

- Maclnnes J. Work-Life balance in Europe: A response for the baby bust or reward for the baby boomers? European Societies, 2006, vol. 8 (2), pp. 223–249. DOI: 10.1080/14616690600644988

- Rozhdestvenskaya E.Yu. Academic careers of women: The balances and mbalances of life and work. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: ekonomichekie i sotsial'nye peremeny=Public Opinion Monitoring: Economic and Social Changes, 2019, no. 3, pp. 27–47. DOI: 10.14515/monitoring.2019.3.03 (in Russian).

- Remery C., Schippers J. Work-family conflict in the European Union: The impact of organizational and public facilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2019, vol. 16 (22). DOI: 10.3390/ijerph16224419

- Brauner C., Wöhrmann A.M., Frank K., Michel A. Health and work-life balance across types of work schedules: A latent class analysis. Applied Ergonomics, 2019, vol. 81. DOI: 10.1016/j.apergo.2019.102906

- McCanlies E., Mnatsakanova A., Andrew M., Violanti J., Hartley T. Childcare stress and anxiety in police officers moderated by work factors. Policing: An International Journal, 2019, vol. 42 (6), pp. 992–1006. DOI: 10.1108/PIJPSM-10-2018-0159

- Rozhdestvenskaya E.Yu., Isupova O.G. Work-life balance: Family, leisure, and professional activity. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: ekonomichekie i sotsial'nye peremeny=Public Opinion Monitoring: Economic and Social Changes, 2019, no. 3, pp. 3–7. DOI: 10.14515/monitoring.2019.3.01 (in Russian).

- Kalabikhina I.E., Shaikenova Zh. D. Estimation of time transfers within households. Demografichiskoye Obozrenie=Demographic Review, 2019, no. 5 (4), pp. 36–65 (in Russian).

- Patrushev V.D. Zhizn' gorozhanina (1965–1998) [Life of a Citizen (1965–1998)]. Moscow: Academia, 2000.

- Nartova N.А. Motherhood in contemporary Western sociological debate. Zhenshhina v rossiiskom obschestve=Woman in Russian Society, 2016, no. 3 (80), pp. 39–53 (in Russian).

- Avdeeva A., Isupova O., Kuleshova A., Chernova Zh., Shpakovskaja L. Roditel'stvo 2.0: Pochemu sovremennye roditeli dolzhny razbirat'sa vo vsem? [Parenting 2.0: Why modern parents should understand everything?] Moscow: Alpina Publisher, 2021. 164 p.

- Isupova O.G. Intensive motherhood in Russia: Mothers, daughters, and sons in school growing. Neprikosnovennyi zapas. Debaty o politike i kul'ture=Inviolable Reserve. Debates about Politics and Culture, 2018, no. 3, pp. 180–189 (in Russian).

- Olivetti C., Petrongolo B. The economic consequences of family policies: Lessons from a century of legislation in high-income countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2017, vol. 31 (1), pp. 205–230. DOI: 10.1257/jep.31.1.205

- Stanczyk A. Does paid family leave improve household economic security following a birth? Evidence from California. Social Service Review, 2019, vol. 93 (2). DOI: 10.1086/703138

- Breeschoten L., Evertsson M. When does part-time work relate to less work-life conflict for parents? Moderating influences of workplace support and gender in the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Community, Work & Family, 2019, vol. 22 (5), pp. 606–628. DOI: 10.1080/13668803.2019.1581138

- Beham B., Drobnič S., Präg P., Baierl A. & Eckner J. Part-time work and gender inequality in Europe: A comparative analysis of satisfaction with work–life balance. European Societies, 2019, vol. 21 (3), pp. 378–402. DOI: 10.1080/14616696.2018.1473627

- Gehl J. Cities for People. Moscow: Alpina Publisher, 2012. 276 p.

- Bor'ba za gorozhanina: Chelovecheskii potentsial i gorodskaya sreda [Struggle for the citizen: Human potential and urban environment]. Ed. by A. Vysokovsky. Moscow: NRU HSE Graduate School of Urbanism; IV Moscow Urban Forum, 2014. 102 p.

- Kabisch S., Koch F., Gawel E., Haase A., Knapp S., Krellenberg K., Nivala J., Zehnsdorf A. Urban Transformations: Sustainable Urban Development through Resource Efficiency, Quality of Life and Resilience. Dordrecht: Springer, 2018. 384 p. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-59324-1(2018)

- Naberushkina E.K. A city for everyone: Sociological analysis of accessibility of urban space for disabled people. Zhurnal sotsiologii i sotsialnoy antropologii=The Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology, 2011, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 119–139 (in Russian).

- Shabunova A.A., Natsun L.N. The urban environment accessibility for people with disabilities. Voprosy territorialnogo razvitiya=Territorial Development Issues, 2014, no. 3 (13), pp. 1–15 (in Russian).

- Lebedeva E.V. Children and youth in a modern city: Sociological analysis. Sotsiologiya=Sociology, 2013, no. 2, pp. 122–132 (in Russian).

- Filipova A.G., Lebedeva E.V. Child and youth friendliness of the urban environment: From theoretical approaches to expert interpretations. Oikumena. Regionovedcheskie issledovaniya=Ojkumena. Regional Researches, 2019, no. 2. pp. 101–112 (in Russian).

- Balakireva M.S. Everyday mobility study of town dwellers with children: Application of mixed method research strategy. Interaktsiya. Interv'yu. Interpretatsiya=Interaction. Interview. Interpretation, 2015, no. 10, pp. 60–69 (in Russian).

- Shpakovskaya L.L., Chernova Zh.V. A family-friendly city: A new public space for children and their parents. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: ekonomichekie i sotsial'nye peremeny=Public Opinion Monitoring: Economic and Social Changes, 2017, no. 2, pp. 160–177 (in Russian).

- Kienko T.S. Elderly citizens and the audiovisual environment of the city: Age as a factor of solidarity with space. Zhurnal sotsiologii i sotsialnoy antropologii=The Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology, 2019, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 57–87. DOI: 10.31119/jssa.2019.22.4.3 (in Russian).

- Van Hoof J., Kazak K.J., Perek-Białas M.J., Peek T.M.S. The challenges of urban ageing: Making cities age-friendly in Europe. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2018, vol. 15. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph15112473

- Glazychev V.L. Sotsial'no-Ekologicheskaya Interpretaciya Gorodskoy Sredy [Socio-Ecological Interpretation of Urban Environment]. Moscow: Nauka, 1984. 180 p.

- Dridze T.M. Human and urban environment in predictive social design. Obschestvennye nauki i sovremennost'=Social Sciences and Contemporary World, 1994, no. 1, pp. 131–138 (in Russian).

- Moreno C. Droit de cité, de la “ville-monde” à la “ville du quart d’heure”. De l’Observatoire, 2020. 179 p.

- Mulíˇcek O., Osman R., Seidenglanz D. Urban rhythms: A chronotopic approach to urban timespace. Time & Society, 2014, vol. 24 (3), pp. 304–325. DOI: 10.1177/0961463X14535905

- Maksimov A.M., Nenasheva M.V., Vereshchagin I.F., Shubina T.F., Shubina P.V. Creating a comfortable urban environment: Problems of interaction between society and government in the implementation of priority projects at the management municipal level. Ekonomicheskiye i sotsialnye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, Prognoz=Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 2021, vol. 14, no. 1. pp. 71–90. DOI: 10.15838/esc.2021.1.73.6 (in Russian).