What will be the emerging new world order?

Автор: Sapir Ja.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Public administration

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.16, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

A new “world order”, a notion that originated with the idea of an institutionalization of international relations that developed at the beginning of the 17th century, is emerging. The old “world order”, inherited from the end of the Second World War and essentially centered on Western countries and the United States, had become dysfunctional since the beginning of the 1990s. It had gradually fragmented since the international financial crisis of 2008-2010. We can follow the trace of this fragmentation in the study of international trade, in the failures suffered by the United States in its multiple military interventions, but also in the emergence or re-emergence of new economic powers. The two major shocks constituted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the international crisis that has unfolded since the start of the conflict in Ukraine have put an end to it. This new world order will likely unfold based on the probable development of the BRICS. It could give rise to more balanced international relations. This could allow a new social contract to emerge in many countries.

World order, globalization, brics, free trade, protectionism, sovereignty

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147241623

IDR: 147241623 | УДК: 327 | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2023.4.88.2

Текст научной статьи What will be the emerging new world order?

We are at the dawn of a new world order. The transformations that have affected the geostrategic balance of power, but also the economic balance of power and the rules and practices of international trade, attest to this. The world order that emerged from the end of the Cold War, and which was marked by the domination that was intended to be undivided by the American Hyper-Power1 (Vedrine, 2000), has gradually fragmented. But what will emerge from this fragmentation is not yet fully defined. A new world order more respectful of the rights of Nations, more centered on the common problems of these Nations, problems which range from the protection of the environment to the social and economic development which remains to be accomplished in many countries, and finally better compatible with the emergence of a social contract of progress within each of them, is undoubtedly the most important challenge that we will have to face in the coming years.

These problems will then be addressed starting by recalling what a world order is, how the dominant world order since 1992 had begun to fragment from the financial crisis of 2008–2010, and how successive shocks – ranging from the COVID-19 pandemic to the new geostrategic situation unfolding since February 2022 – have accelerated this fragmentation and shaped the contours of a new world order. The consequences that this may have on the form and content of the social contract, in other words the dialectic between external factors and internal factors of change, will then be specified. Will these factors go in the direction of social progress or in the direction of regression? This question must also be asked. This will then allow us to try to conclude by seeking to clarify whether we are indeed today in the presence of what could be called a global moment of pivoting of the great balances.

What is a world order?

The phrase “change in the world order” has undoubtedly been widely used since the end of February 20222, but with different contents. The notion of world order is born with the institutionalization of international relations, an institutionalization that must be linked to Hugo de Groot (Grotius) who, at the beginning of the 17th century, has revolutionized the vision of Law concerning States (Gurvitch, 1927). Prior to Grotius, rights were essentially seen as attached to objects. He introduced a notion of rights belonging to persons3, be they moral or physical, meaning then the expression of a capacity to act or the means to achieve such and such a thing. It is therefore between the end of the Wars of Religion and the emergence of what is called the “classical period”, that this idea of international law and consequently of a world order gradually emerged (Besson, 2020). These ideas would be found in the Treaty of Westphalia4 (Blin, 2006) and, later, in the 19th century, in the Congress of Vienna of 1815 (Lentz, 2013; Jarrett, 2013).

Grotius’ ideas have known a new youth between the end of the 19th century and the attempts to limit the violence in armed conflicts (Boidin, 1918; Pillet, 1918), and the first world conflict with the

Treaty of Versailles5, the birth of the League of Nations in 1920 (Haakonssen, 1985), and then in 1944–1945 with the United Nations6. These concepts quickly found their way in the economic field with the Bretton-Woods agreements in 1944 (Steill, 2013), the Havana Treaty (Steill, 2013) and the creation of the GATT. Behind the expression world order, there is therefore all the power relations between States, power relations that are both institutionalized and determined by the rules of international law (Besson, 2020). It is understood that the application of rules, which are grouped under the term international law, is a better thing than the application of naked force. It is still necessary, however, that these rules are applied equally to all countries and that a country does not decide on its own to create new rules without consultation with the other Nations. This was recalled by Vladimir Putin on February 10, 2007 during his speech at the Munich Security Conference7 (Levesque, 2007). This is today China and India’s position in the face of what it perceives as the application of a “double standard” regarding Russia’s position8.

This world order was hegemonized by a great power, Great Britain before 1914 and the United States since 1945 and in particular since 1991. This poses the problem of relations between dominant countries and dominated countries. Such a world order has never been egalitarian between the nations concerned, and this is particularly the case for the international economic order embodied by the WTO (Galbraith, Choi, 2020). It has disadvantaged formerly colonized countries (or created by colonization) and globally less industrialized countries (Subramanian, Wei, 2007) and ended in an agreement of rich and powerful countries (Gowa, Kim, 2005). No wonder it was challenged and constantly evolved.

From 1949, it included only the allied countries of the United States and excluded, in fact, the USSR, China, and all the communist countries. It changed again in the early 1970s when the United States imposed the principle of floating exchange rates (Glenn, 2007). In fact, with the decomposition of the Bretton-Woods agreements, the notion of the international monetary system or the international monetary order made its appearance. This leads to a focus on the role of the United States dollar (Eichengreen, 2011).

The idea of the emergence of a “new” world order has been emerging since the early 2000s (Sapir, 2008). This world order would be truly multipolar. Undoubtedly, the first to have spoken of it was John Maersheimer (Mearsheimer, 2001). It has been noted that the world order, resulting from the end of the USSR, has been challenged by the rise in power of emerging economies (Goldstein, 2005; Rosecrance, 2006; Struye de Swielande, 2008). With this idea also emerged the notion that a conflict between the United States and China was possible, then to be feared and even inevitable (Swaine, Tellis, 2000; Friedberg, 2005; Wang, 2006).

International trade since the financial crisis of 2008–2010 and the fragmentation of the world order

The world order has always reflected the balance of power. It has not only reflected the differences in wealth between nations, but also their implicit or explicit geostrategic power. The United States had emerged from the disappearance of the Soviet Union, as the hegemonic power holding a form of world imperium (Poirier, 1991). In the last decade of the 20th century, they had total supremacy, both military and economic, both political and cultural. American power then brought together all the characteristics of “dominant power”, imposing its explicit and implicit representations (Dahl, 1957). However, this hegemony, which is also reflected in the generalized adoption of free trade rules with the transition from GATT to the WTO in 19949, would gradually crumble in the face of financial crises that the United States will not be able to control, of military failures (in Iraq and Afghanistan), and of the rapid emergence of new powers (China, India, Brazil) or old ones that have known how to reinvent themselves (Russia) (Primakov, 2002).

The financial crisis of 2008–2010, known as the “subprime crisis”, was an important moment in the questioning of the world order that had appeared in 1991–1992, just as it was a major shake-up in the economic world order (Sapir, 2009). But it was not the only one. The financial crisis known as the “Asian crisis” of 1997–1998 largely foreshadowed it (Sapir, 2008). In fact, this world order which resembled a Pax Americana was rapidly breaking down both because of the incapacities and mistakes made by the leaders of the United States and because the rise of other powers. Globalization, which had been accepted as the sole framework for economic activities, was in fact beginning to crumble and to be called into question even before

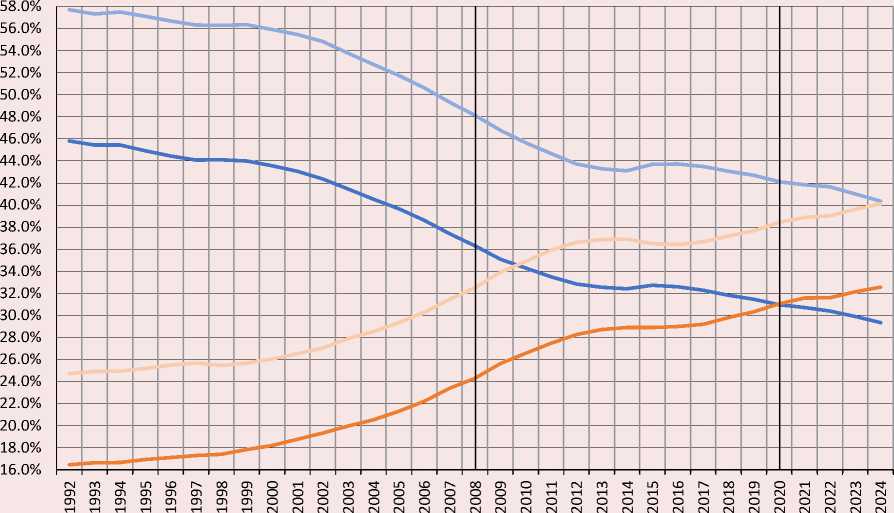

Figure 1. Share of the World GDP (in PPP)

:: ' ■ G7 ^^^^^^^е G7+Friends ^^^^^^^е BRICS BRICS + countries in a process of BRICS adhesion

Note. G-7 members: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, United Kingdom, United States of America; BRICS members: Brazil, China, India, Russia, Republic of South Africa; countries considered as G-7 allies: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, South Korea, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Singapore, Spain, Sweden; countries that have put forward their candidacies for membership in BRICS: Algeria, Argentina, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Egypt, UAE, Indonesia, Iran.

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook (April 2023) database.

the 2008–2010 crisis (Bello, 2002), a disintegration which was naturally accelerating following this crisis (Sapir, 2011).

In fact, if we compare the countries that today form the BRICS to the G-7 group, we see that their share in world GDP (calculated in PPP) was respectively 46 and 16% in 1992.

By 2008, when the “subprime crisis” started, it has risen to 36% for the G-7 and 24% for the BRICS. When the COVID-19 pandemic hits, in 2020, G-7 countries and BRICS were tied at 31%. If we now look at the respective share of the G-7 group and “allies” and that of the BRICS and identified countries having officially requested their membership of the BRICS in 202310, the evolution is even more striking. Their shares were 58 and 25% of world GDP in 1992 and 41 and 39% in 2020. The transformation of economic power relations has been a massive reality over the past thirty years and marks the end of an economic order too exclusively centered on Western countries.

This economic order was based on an internal social order. Globalization had allowed the establishment of a particular social contract from the years 1980-1990. In exchange for low wages, justified by low inflation induced by global competition resulting from the opening of economies following the free trade agreements which multiplied with the transformation of the GATT into the WTO in 1994 (and in “single market”11) but also imposed by high unemployment (Duval, 2018; Armstrong, Taylor, 1981) (fed by immigration flows), the working classes of developed countries were offered low-cost consumer products from newly industrialized countries (Bourguignon, 2012). This made the system bearable, despite a sharp rise in social inequalities12 induced by the domination of the financial sphere and associated activities. The rapid development of the financial sphere since the end of the 1990s has generated a rentier system of a specific nature (Ryan et al., 2014; Ratti et al., 2008; Amable, Chatelain, 1996) which takes a large part of the value created in productive activities. This distortion in the distribution of income, leads to a tendency to the disappearance of the middle classes (Freeland, 2012), and to the territorial relegation of these former fallen middle classes (Guilluy, 2022a; Guilluy, 2022b). The planned destruction of a large part of industry, with the exception of certain sectors which were more or less preserved, fed this unemployment, forced these economies to an accelerated tertiarization and induced social changes which ended in fragmenting society, resulting in what a sociologist called an “archipelago society” (Fourquet, 2019). The resulting protest movements, from the “yellow vests” (Bendali et al., 2019; Tartakowsky, 2019) to the 2023 movement against pension reform in France, but also Brexit in the United Kingdom and the election of Donald Trump in the United States (Espinoza, 2021), testify to the social crisis induced by this development model. The fact that Brexit caused the start of political reconfiguration in Great Britain13, culminating in Boris Johnson’s landslide victory in the late 2019 election14, was a good symptom of this. The rise of populist politics was a consequence of the society fragmentation15. The violence of police

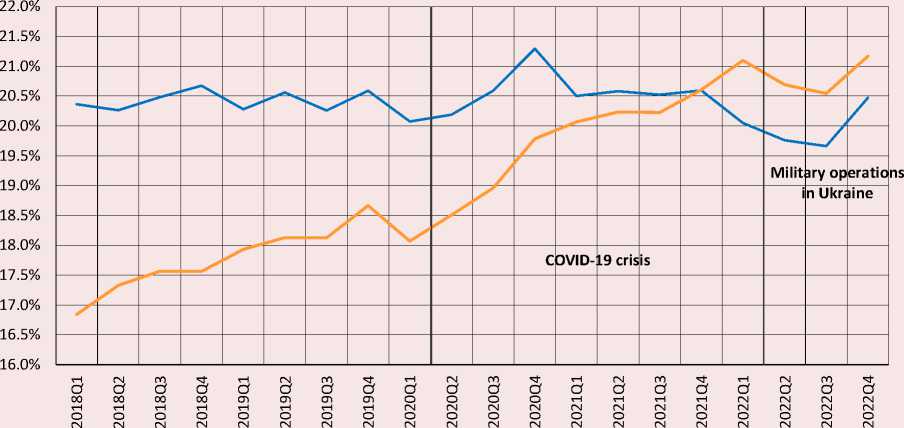

Figure 2. Share in global exports

BRICS BRICS + countries in a process of joining BRICS ' ■ E U + USA + Japan + South Korea

Source: WTO

repression, particularly in the case of the “yellow vests” movement (Poupin, 2019), also indicates the extent to which the internal social order has been challenged by this movement. World order changes reflect but also challenge the social pact.

If it is not wrong to speak of a de-globalization of the world, it has also to be understood as a dewesternization of the latter (Barma et al., 2009). The relevance of Chinese or Russian initiatives toward Africa is just an example16. This probably is the reason why these changes are so strongly opposed by Western countries.

This process of de-globalization is not limited to the simple power of economies. It implies a progressive questioning of the rules of the WTO and generalized free trade and multilateralism. The crisis of the multilateral trading system is in fact profound and reflects the questioning of the international economic order17. Thus, the WTO finds itself in competition with bilateral, regional and mega-regional agreements, including in the area of dispute settlement, for which arbitration mechanisms are provided. It would seem that the WTO is unable to adapt to the new context of the conduct of economic policies while it is “called upon to reinvent itself”18. It is there, in reality, that we measure the limits of the attempt to impose a form of world order by rules which, at a time, are no longer bearable by groups of countries19 (Dunoff, Pollack, 2017).

Table 1. BRICS shares in multilateral institutions

|

World Bank |

IDA |

MIGA |

IMF |

SDR Quota |

||||||

|

Country |

number of votes |

% of total |

number of votes |

% of total |

number of votes |

% of total |

number of votes |

% of total |

Million |

% of total |

|

Brazil |

54,264 |

2.11 |

478,0 |

1.66 |

2,83 |

1.3 |

111,9 |

2.22 |

11,0 |

2.32 |

|

Russia |

67,26 |

2.62 |

90,65 |

0.31 |

5,752 |

2.64 |

130,5 |

2.59 |

12,9 |

2.71 |

|

India |

76,777 |

2.99 |

835,2 |

2.89 |

1,218 |

0.56 |

132,6 |

2.63 |

13,1 |

2.76 |

|

China |

131,426 |

5.11 |

661,0 |

2.29 |

5,754 |

2.64 |

306,3 |

6.08 |

30,5 |

6.41 |

|

South Africa |

18,698 |

0.73 |

74,37 |

0.26 |

1,886 |

0.86 |

32,0 |

0.63 |

3,1 |

0.64 |

|

Total |

348,425 |

13.56 |

2,139,1 |

7.41 |

17,44 |

8.0 |

713,2 |

14.15 |

70,6 |

14.84 |

|

Note: IDA – International Development Association; MIGA – Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; IMF – International Monetary Fund; SDR – Special Drawing Rights. Source: (Liu, Papa, 2022). |

||||||||||

At the same time, the share of BRICS countries in international trade continued to rise ( Fig. 2 ).

It should also be noted that the BRICS countries remain largely under-represented, whether in relation to their share in world GDP or in world trade, in international organizations ( Tab. 1 ), a fact which can only weaken the legitimacy of the (old) world order.

But the questioning of multilateralism was actually initiated by one of the countries that had done the most to impose it: the United States. The implementation of various measures, such as the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, a law passed in 197720 but which took on its full importance with a 1998 amendment and its aggressive application by the end of 2000s21, and the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act of 2010, was considerably aggravated by the decision of the American authorities to consider that any use of the Dollar automatically brought foreign companies under the scope of American law. This is called the principle of extraterritoriality. A French parliamentary report on this problem was written in 201622. The main problem comes from the fact that the transactions that had to be honored are contracts made in dollars. However, in this case, the transactions necessarily need to pass through an American bank to “buy” dollars, thus falling under American law. French companies (Alstom23, Technip) and banks (BNP-Paribas, then Credit Agricole and Societe Generale) were condemned via these procedures.

These measures have continued under the administration of Donald Trump. Moreover, in 2014, the European Union rallied to a policy of economic sanctions against Russia and did not react in practice to the sanctions decided by the United States against Iran24. Through this policy of “economic sanctions”, whether they target Cuba, Iran, Russia or Venezuela, the United States and the European Union25, which were at the front of the globalization process have therefore accelerated the phenomenon of de-globalization.

The US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action 26 (the agreement with Iran) was not exclusively aimed at isolating Iran through economic sanctions. For fear of reprisals due to the extraterritorial application of American law, the denunciation of this agreement made it possible to strike France and Germany. Apart from Italy and Greece, which negotiated directly with the United States bypassing Brussels, no other European state has so far been able to benefit from American exemptions on Iranian oil exports. This unilateral withdrawal has had heavy economic repercussions for European companies and in particular French companies such as PSA, Renault, Total and Airbus27.

By showing that trade, and the standards associated with it, could be manipulated or interrupted for essentially political reasons, the United States demonstrated that these trades and these standards corresponded less to a world order than to the policy of United States (Kirshner, 2008). A note from the DGSI28 thus establishes that “ French companies operating in these sectors (high-tech sectors such as aeronautics, health and research) are the subject of targeted attacks, in particular through legal disputes, attempts to capture information and economic interference ”29.

Finally, the international order has also crumbled in the monetary field. This was based, since the end of the Bretton-Woods agreements in 1973, on

Figure 3. Currencies share in Central Bank reserves

USD share EURO share former European currencies share

Source: IMF, COFER,

a system that can be described as a dollar standard30 and which quickly raised many criticisms (Ghymers, 1986). This system has always been dysfunctional (Aglietta, 1986), but this became evident in the early 2000s31. The creation of the EURO in 1999 had not changed this situation (Begg et al., 1998), insofar as the share of the EURO in the reserves of the various Central Banks had not exceeded the sum of the shares of the currencies of the countries which had adopted this single currency. This share, after experiencing a movement bringing it closer to the sum of the existing European currencies before the Euro, has also experienced a fairly significant drop from 2010. The share of the US dollar has also fallen, but it remained above 60% before the COVID-19 crisis ( Fig. 3 ).

If both the Dollar and the Euro fell, it was due to the rise of “other currencies” used as reserves by central banks. It was therefore clear, and this from 2010, that we were in the presence of a trendtowards fragmentation of the international monetary system, a trend partly induced by geopolitical security reasons (McDowell, 2020). This trend is nevertheless slow. For institutional reasons, such as its massive use as a unit of account in many commodity markets, as well as for reasons of practical expediency (Gopinath, Stein, 2021), the dollar still remained, on the eve of the pandemic, the dominant currency of the international monetary system (Helleiner, Kirshner, 2009).

Globalization, as we have known it in the 1990s and the 2000s may well have been doomed from the start (Galbraith, 1999). But roots of this were going much farther than just the crisis of the “Washington

Consensus” (Sapir, 2000). The huge development of inequalities (Atkinson et al., 2011) which was linked to the development of the world order emerging since 1991 has undermined it (Galbraith, 2012). These inequalities have a direct link with financial crisis that shattered the world order (Lysandrou, 2011; Rajan, 2010).

The shock of COVID-19 and the upheaval of the geopolitical situation

These trends were discernible as early as 2010, and the end of what some authors have called hyper-globalization32. However, they acquired a new reality between 2020 and 2023.The world has suffered a series of unparalleled health, economic and geopolitical shocks. The consequences will only be fully perceived by the end of the decade. The multiple breaks in the supply chains supplying production, due to COVID-19 (Fulconis, Pache, 2020), have undermined a globalized economy and raised awareness in many countries of the vulnerability arising from these chains. These breaks seem to have had a greater effect in 2021 in economies where the industrial apparatus was significant (Germany) than in economies where the share of services was greater (Dauvin, 2022). Two authors were able to write that this crisis had resulted in a weakening of supply chains, due to the absence of substitute suppliers outside the usual production clusters (Derrien, Van Der Putten, 2021).

Naturally, the new sanctions imposed on Russia from the end of February 2022 imposed new shocks. These sanctions were added to those that had been applied since 2014/201533. The new sanctions had a monetary and financial component (ban on

Table 2. Growth rates of major groups of economies since the COVID-19 outbreak, %

2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 World 2.80 -2.80 6.30 3.40 2.80 3.00 Advanced economies 1.70 -4.20 5.40 2.70 1.30 1.40 of which: European Union 2.00 -5.60 5.60 3.70 0.70 1.60 of which: Euro area 1.60 -6.10 5.40 3.50 0.80 1.40 United States 2.30 -2.80 5.90 2.10 1.60 1.10 Japan -0.40 -4.30 2.10 1.10 1.30 1.00 Emerging market and developing economies 3.60 -1.80 6.90 4.00 3.90 4.20 of which: Emerging and developing Asia 5.20 -0.50 7.50 4.40 5.30 5.10 Emerging and developing Europe 2.50 -1.60 7.30 0.80 1.20 2.50 Note. 2023 and 2024 are forecasts; 2022 are estimates. Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook, Appendix A. Available at:

supplying Western currencies to the Central Bank of Russia, exclusion of certain Russian banks from the SWIFT system34), and an embargo-like commercial component35.

In addition to the sharp reduction in trade between European Union countries and Russia, these sanctions have led to the segmentation of world trade between countries applying the sanctions, such as the United States, Canada, European Union countries, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand and countries refusing to apply them such as China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, countries in the Middle East (including Turkey, despite being a NATO member), the countries of Africa and most of the countries of Latin America. If the discourse on the “isolation” of Russia seems to be a fantasy of the West36, the segmentation of world trade is a reality. Moreover, and this even before the sanctions, Russia had, it seems, taken precautions in the face of the threat of new sanctions37.

Sanctions, and the creeping segmentation of international trade that they have induced, have had significant consequences for global growth. In addition to the acceleration of inflation initially caused by the COVID-19 crisis, they have increased the gap between emerging and developing countries, and in particular those in Asia and developed countries.

The countries of the European Union thus appear to be notoriously lagging behind (Sapir, 2021). Not only have they suffered a greater shock following the COVID-19 pandemic, and this despite public aids which have been considerable (Sapir, 2021), but their economic recovery has been slower. The geopolitical upheavals that have affected the world since February 2022 have led to lower growth, and this can be seen in particular in the forecasts made for 2023 and 2024.

From this point of view, the application of the sanctions had at least as great a deleterious effect on the economies that decided on these sanctions (and

Figure 4. Shares of US dollars in Central Bank reserves

63.0%

62.5%

62.0%

61.5%

61.0%

60.5%

60.0%

59.5%

59.0%

58.5%

58.0%

57.5%

57.0%

Source: Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER), International Financial Statistics (IFS). Available at:

Figure 5. Shares of Euro and other currencies in Central Bank reserves

^^^^^^^^^^е Share of euro ^^^^^^^*Share of other currencies

Source: Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER), International Financial Statistics (IFS). Available at: in particular those of the European Union) as on the targeted country, Russia (Sapir, 2023). This is also reflected in an acceleration of developments concerning currencies. The US dollar seems to be accelerating its decline in the share of central bank reserves. In fact, the trends towards de-dollarization of international trade (Ladasic, 2017), and in particular the project of a common BRICS currency (Liu, Papa, 2022), seem to have been induced by the political instrumentalization of the US dollar as well as by the freezing of the assets of the Central Bank of Russia38 (Fig. 4).

It should be noted that this process did not fundamentally benefit the Euro but all the “other currencies”, including the convertible Yuan, the Swiss Franc or the Pound Sterling ( Fig. 5 ). In fact, we are indeed in the presence of a movement to question the international monetary system, in other words the world monetary order.

The crisis of the world order dating from 1992 has become evident with the crisis caused by COVID-19 and the geostrategic upheavals that have occurred from 2022. The chief economist of the World Bank, Ms. Carmen Reinhart, recognized it herself: “COVID-19 is the last nail in the globalization coffin”39.

She is not the only one. Mr. Kemal Dervis, in a column published in June 2020 by the Brookings Institution, one of the most famous “think tanks” of the US Democratic Party added: “With the COVID-19 catastrophe having laid bare the vulnerabilities inherent in a hyper-connected, just-in-time global economy, a retreat from globalization increasingly seems inevitable. To some extent, this may be desirable.”40. This statement is significant, because the Brookings has been one of the centers of influence that have worked the most for “globalization”. Some drew attention to this phenomenon before the health crisis, such as that of Harold James, written for the anniversary of the 2008 crisis (James, 2018). This same Harold James, professor of history and international relations at Princeton University, also spoke of the “global challenge” represented by this de-globalization41. In 2022, Joseph Stiglitz pointed out to phenomena of “re-shoring” and “friendly-shoring”, which testify to a process of fragmentation and deglobalisation, by showing how they can appear as a response to the errors of globalization42. In her October 2022 speech at Georgetown University (Washington DC), Kristalina Georgieva, President of the IMF, took note of these transformations43. The Free Trade paradigm has been shattered. The return of protectionism, which had begun to manifest itself openly with the crisis of 2008– 2010, tends – because of sanctions and countersanctions – to accelerate.

We are now in the presence of a clear risk of a segmentation of the world between what could be called a “collective West” and a “collective South”44. The latter tends to be structured around the BRICS, this is measured in terms of applications for membership, but also – and this is less noticed – around the SCO (Deng, 2021). Even if this opposition is inevitable because of the behavior of countries like the United States or Great Britain, whose former Prime Minister Mrs. Truss called for forming the G-7 into an economic NATO45, we cannot be satisfied of this situation which is clearly sub-optimal in terms of dealing with issues of safeguarding the planet and equal development. If a new world order will eventually emerge, it is possible that it will be, because it is multipolar, much less unequal than the one to which it will succeed.

What evolution for the internal social contract of countries?

Changes in the world order that have been witnessed since the end of 2019 have meant the end of the implicit social contract that has dominated in developed countries. This has resulted in a sharp rise in prices46, largely due to the breakdown of global supply chains47 and, secondarily, the consequences of economic sanctions and the disruptions they have caused in world trade. But we have also witnessed an awareness, more or less rapid and more or less significant depending on the country considered, that the continuation of the growth model linked to deindustrialization was no longer possible48. This awareness is naturally faster in Europe, which finds itself directly threatened by the breakdown of economic relations with Russia49, and which runs the risk of a growing marginalization (and even vassalization) under the tutelage of the United States in the future world order50.

Moreover, awareness of the ecological limits of the old growth model, limits which are too often reduced to the question of climate change but which in reality include the question of waste and soil and water pollution, has also asserted itself through the social shock induced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

For other countries, including Russia, the development strategy adopted since the 2000s and based on reciprocal ties of dependence with European economies, ties formed by the sale of cheap energy or cheap products in exchange for investments industries and imports of technology, which has been invalidated. Against a backdrop of strong economic growth, Russia had actively attracted foreign direct investment and localized productions using foreign technologies (Adewale, 2017). This model was shattered with the new round of sanctions. With the new geostrategic situation that has been developing since February 2022, a new development model seems to have to prevail51 (Gusev, 2023), even if today it is the medium-term constraints (and opportunities) that remain important (Shirov, 2023). The case of the automobile industry is the best known, but it is far from being the only one. Russia was then forced to accelerate its import-substitution strategy52, and it seems to give positive results53. This allowed a beginning of diversification of exports, corresponding moreover to the canonical model of international trade (Krugman, 1984).

Russia is not alone in this case. India could well, within a few months, be faced with a similar challenge. Finally, China has started to refocus on its internal market54 and could be driven to accelerate this process55. Overall, the degree of openness of the BRICS has tended to decrease in the ten years since the 2008-2010 crisis. The BRICS countries have sought to reduce their dependence on international trade and this process should naturally accelerate in the current circumstances marked by an increasing politicization of international trade.

For developed countries, the old strategy, or the old model of growth, could be measured by the share of services in GDP, a share that has grown steadily since the 1970s and which today has become very important ( Tab. 3 ). This share fluctuates between 69 and 79%.

Figures for China and India have been presented here for the sake of comparison. The average is between 49 and 58%. As can be seen in Table 4, Western countries have seen their economies become massively tertiarized (Barreiro de Souza et al., 2016; Greenhalgh, Gregory, 2001; Daniels, 1993). This phenomenon is not new (Lichtenstein, 1993), and in a number of cases it can even be justified. But it was probably brought to its climax by the extension of free trade and the implicit social contract it enabled. Indeed, China’s level of development is similar to Western countries, but the share of services is much lower there. However, services – except for certain sectors such as financial services – offer lower wages than in industry and construction.

From this point of view, it is interesting to look at the observed and probable evolution of Russia ( Tab. 4 ). In 2016, it was close to Germany and in an overall intermediate situation between developed countries and China. It seems, since the beginning

Table 3. GDP percent of different economic sectors, average 2011–2018, %

Sectors France Germany Italy United States Japan* China India** Agriculture, forestry, fishing 1.8 0.9 2.2 1.1 1.0 8.6 16.4 Industry 14 25.6 19 15.7 23.4 35.7 18.9 Construction 5.7 4.6 4.7 3.9 5.5 6.9 7.0 Services 78.5 68.9 74.1 79.3 70.1 48.8 57.7 Note. * Average 2016–2021; ** average 2016–2019. Sources: IMF, OECD,

Table 4. GDP percent of different sectors in the Russian economy, %

Economic sector 2016 2022** 2023*** Agriculture, forestry, fishing 4.8 4.3 4.3 Industry* 25.7 31.1 31.6 Construction 6.2 5.2 5.3 Services 63.3 59.4 58.8 Note. * Incorporating transport of electricity, heat, gas and water; ** estimates; *** forecasts. Sources: OECD, ROSSTAT

52 Adamovich A. Russia is switching to a new format of import substitution. Available at: 27289/4427120/

53 The Atlantean shrugged his shoulders: How the Russian auto industry is recovering and developing. Available at:

54 China’s Structural Transformation: What Can Developing Countries Learn. Geneva, UNCTAD, GDS/2022/1. Available at:

55 Available at:

of the armed clashes in Ukraine, to have taken another path and tends to approach India and China.

The government’s policy seems to be taking the direction of what a Ukrainian sociologist described as “military Keynesianism”56, through significant aid to sections of the population engaged in the war effort, but also through the volume of public orders for armament57 and infrastructure. The production capacity utilization rate58, a good indicator of industrial activity, would have reached – according to information communicated by UNICREDIT59 – 86% at the start of 2023 is currently more generally around 78 to 82% depending on the country60. This implies that industrial activity is currently very high in Russia. If we add to this the efforts made to achieve the substitution of national products for part of the imports, a development model based on industry, on the processing of raw materials and not on the export of raw materials, could be set up. Such a model would logically be more egalitarian, whether socially or territorially, than the reciprocal dependency model developed previously. It will likely require some form of planning61.

For Western countries, such a change raises many problems. If the objective of re-industrialization, coupled with that of making industry much more compatible with ecological requirements, has indeed been adopted in France as in the United States, and in this country the IRA law bears witness to this62. This objective implies colossal investments, in particular to decarbonize energy production. It also implies putting the financial sector at the service of an economy centered on the production of goods and on public services and a coordination of efforts which also does not seem possible without some form of planning (Sapir, 2022). The reduction of inequalities that could result from this would be favorable to the reconstitution of the social basis of democracy. But we can see a significant gap forming between political speeches and the reality of action. The case of the pension reform in France in the first quarter of 2023 clearly shows that the financial dimension remains very present within the government’s economic policy. Moreover, the rise of authoritarian behavior within the government apparatus as well as the radicalization of political speeches raise fears of another outcome than that of the reconstruction of the social pact on the basis of re-industrialization.

Since the beginning of 2022, we have witnessed an acceleration of the transformations that had already been at work for at least a decade in the global economy. These transformations sign the death warrant for the world order that emerged in the early 1990s, a death warrant which takes the form of the rise of non-Western organizations (BRICS, OCS) in international life, and a questioning of the international monetary system. The world order change takes the form of a deWesternization of the world and intends, rightly or wrongly, to sink its roots into the decolonization movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

But these transformations also affect the social pact, whether implicit or explicit, that worked in most developed and developing countries. It confronts both groups of countries with the impossibility of continuing on the path that has been theirs since the beginning of the 1990s. In both cases the state will be called upon to play a greater role – directly and indirectly – in economic activity and the structuring of society. However, it is not certain that this role would result in significant social and democratic progress and it could, on the contrary, end – in developed countries – in a more coercive and more unequal internal order.

Список литературы What will be the emerging new world order?

- Adewale A.R. (2017). Import-substitution industrialization and economic growth – Evidence from the group of BRICS countries. Future Business Journal, 3, 138–158.

- Aglietta M. (1986). La Fin des Devises Clés. Paris: La Découverte.

- Ammable B., Chatelain J.B. (1996). La concurrence imparfaite entre les intermédiaires financiers est-elle toujours néfaste à la croissance économique? Revue économique, 47(3), 765–775.

- Armstrong H., Taylor J. (1981). The measurement of different types of unemployment. In: Creedy J. (Ed.). The Economics of Unemployment in Britain. London: Butterworth.

- Atkinson A., Piketty T., Saez E. (2011). Top incomes in the long run of history. Journal of Economic Literature, 49(1), 3–71.

- Atkinson A.B., Piketty T. (Eds.). (2007). Top Incomes Over the Twentieth Century: A Contrast between Continental European and English-Speaking Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Barma N., Chiozza G., Ratner E., Weber S. (2009). A world without the West? empirical patterns and theoretical implications. Chinese Journal of International Politics, 4(2), 525–544.

- Barreiro de Souza K., Quinet de Andrade Bastos S., Salgueiro Perobelli F. (2016). Multiple trends of tertiarization: A comparative input–output analysis of the service sector expansion between Brazil and United States. Economia, 17(2), 141–158.

- Begg D., von Hagen J., Wyplosz C., Zimmermann K.F. (Eds.). (1998). EMU: Prospects and Challenges for the Euro. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Bello W. (2002). Deglobalization, Ideas for a New World Economy. London & New-York: Zed Book.

- Bendali Z. et al. (2019). Le mouvement des Gilets jaunes: Un apprentissage en pratique(s) de la politique? Politix, 128(4), 143–177. Available at: https://www.cairn.info/revue-politix-2019-4-page-143.htm

- Besson S. (2020). The political legitimacy of international law: Sovereign states and their international institutional order. Carrying Dworkin’s later work on international law forward. Jus cogens, 2(2), 111–138.

- Besson S. (2020). L’autorité légitime du droit international comparé. Quelques réflexions autour du monde et du droit des gens de Vico. In: Besson S., Jubé S. (Eds.). Concerter les civilisations. Mélanges en l’honneur d’Alain Supiot. Paris: Seuil.

- Blin A. (2006). 1648. La Paix de Westphalie ou la naissance de l'Europe politique moderne. In: Questions à l'histoire. Bruxelles.

- Boidin P. (1918). Les lois de la guerre et les deux conférences de La Haye (1899–1907). Paris.

- Bourguignon F. (2012). La mondialisation de l’inégalité. Paris: Seuil.

- Bourlange D., Chaney E. (1990). Taux d'utilisation des capacités de production: un reflet des fluctuations conjoncturelles. Économie et statistique, 23, 49–70.

- Dahl R.A. (1957). The concept of power. Behavioral Science, 2(3), 201–215.

- Daniels P.W. (1993). Services Industries in the World Economy. Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Dauvin M. (2022). Évaluation du choc d’approvisionnement. Revue de l’OFCE, 2(177), 101–115.

- Deng H. (2021). 20 years of SCO, development, experience and future directions. Contemporary International Relations, 31(4).

- Derrien G., Van Der Putten R. (2021). Des chaînes d’approvisionnement plus résilientes après la pandémie de la Covid-19. BNP-Paribas Conjoncture. Available at: https://economic-research.bnpparibas.com/html/fr-FR/chaines-approvisionnement-resilientes-pandemie-Covid-19-20/12/2021,44859

- Dunoff J.L., Pollack M.A. (2017). The judicial trilemma. American Journal of International Law, 111, 226–276.

- Duval G. (2018). Travail: du plein-emploi au chômage de masse. Alternatives Économiques, 4(378), 72.

- Eichengreen B. (2011). Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Espinoza M. (2021). Donald Trump’s impact on the Republican Party. Policy Studies, 7-6. Available at: https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1037&context=pol_fac

- Fourquet J. (2019). L’Archipel français. Paris: Le Seuil.

- Freeland C. (2012). Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else. Toronto: Doubleday.

- Friedberg A.L. (2005). The future of U.S.-China relations: Is conflict inevitable? International Security, 30(2).

- Fulconis F., Paché G. (2020). Pandémie de COCID-19 et chaines logistiques. Revue Française de Gestion, 8(293), 171–181.

- Galbraith J. (2012). Inequality and Instability. A Study of the World Economy Just Before the Great Crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Galbraith J., Choi J. (2020). Inequality under globalization: State of knowledge and implications for economics. In: Webster E., Valodia I., Francis D. (Eds.). Inequality Studies from the Global South. London-New York: Routledge.

- Galbraith J.K. (1999). The crisis of globalization”. Dissent. Available at: https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/the-crisis-of-globalization

- Ghymers C. (1986). Réagir à l’emprise du dollar. In: Aglietta M. (Ed.). L’ECU et la vieille dame. Paris: Economica.

- Glenn G.W. (2007). Floating the system: Germany, the United States, and the Breakdown of Bretton Woods, 1969–1973. Diplomatic History, 31(2), 295–323.

- Goldstein A. (2005). Rising to the Challenge. China’s Grand Strategy and International Security. Stanford University Press.

- Gopinath G., Stein J.C. (2021). Banking, trade, and the making of a dominant currency. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136(2), 783–830.

- Gowa J., Kim S.Y. (2005). An exclusive country club: The effects of the GATT on trade, 1950–1994. World Politics, 57(4), 453–478.

- Greenhalgh C., Gregory M. (2001). Structural change and the New Service Economy. Oxford Bulletin of Economic Statistics, 63(special issue), 629–646.

- Guilluy C. (2022a). La France Périphérique. Paris: Flammarion.

- Guilluy C. (2022b). Les Dépossédés, Paris: Flammarion.

- Gurvitch G. (1927). La philosophie du droit de Hugo Grotius et la théorie moderne du droit international (À L'occasion Du Tricentenaire Du De Jure Ac Pacis, 1625–1925). Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale, 34(3), 365–391.

- Gusev M.S. (2023). Russian economic development strategy – 2035: Ways to overcome long-term stagnation. Studies on Russian Economic Development, 34(2), 167–175. DOI: 10.1134/S107570072302003X

- Haakonssen K. (1985). Hugo Grotius and the history of political thought. Political Theory, 13, 239–265.

- Helleiner E., Kirshner J. (2009). The Future of the Dollar. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- James H. (2018). Deglobalization: The rise of disembedded unilateralism. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 10, 219–237. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-financial-110217-022625

- Jarrett M. (2013). The Congress of Vienna and Its Legacy: War and Great Power Diplomacy after Napoleon. London: I.B. Tauris & Company, Ltd.

- Kirshner J. (2008). Dollar primacy and American power: What’s at stake? Review of International Political Economy, 15(3), 418–438.

- Krugman P. (1984). Import protection as export promotion: International competition in the presence of oligopoly and economies of scale. In: Kierzkowski H. (Ed.). Monopolistic Competition and International Trade. London: Oxford University Press.

- Ladasic I.K. (2017). De-dollarization of oil and gas trade. In: 17th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM, 15, 99–106.

- Lentz T. (2013). Le Congrès de Vienne: une refondation de l'Europe (1814–1815). Paris: Perrin.

- Levesque J. (2007). En marge d’un fameux discours de Poutine. Diplomatie, 27, 38–41.

- Lichtenstein C. (1993). Les relations industrie-services dans la tertiarisation des économies. Revue internationale P.M.E., 6(2), 9–33.

- Liu Z., Papa M. (2022). Can BRICS De-dollarize the Global Financial System? Elements in the Economics of Emerging Markets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/elements/can-brics-dedollarize-the-global-financial-system/0AEF98D2F232072409E9556620AE09B0

- Lysandrou P. (2011). Inequality as one of the root causes of the financial crisis: A suggested interpretation. Economy and Society, 40(3), 323–344.

- McDowell D. (2020). Financial sanctions and political risk in the international currency system. Review of International Political Economy, 28(3), 635–661.

- Mearsheimer J. (2001). The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Pillet A. (1918). Les Conventions de La Haye du 29 juillet 1899 et du 18 octobre 1907, étude juridique et critique. Paris.

- Poirier L. (1991). La guerre du Golfe dans la généalogie de la stratégie. Stratégique, 51/52, 3e et 4e trimestres.

- Poupin P. (2019). L’expérience de la violence policière dans le mouvement des Gilets jaunes. Sociologie et Sociétés, 51(1-2), 177–200. Available at: https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/socsoc/2019-v51-n1-2-socsoc05787/1074734ar/

- Primakov E. (2002). Mir posle 11 Sentjabrja. Moscow: Mysl’.

- Rajan R. (2010). Fault Lines. How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ratti R.A., Lee S., Seol Y. (2008). Bank concentration and financial constraints on firm-level investment in Europe. Journal of Banking & Finance, 32(12), 2684–2694.

- Rosecrance R. (2006). Power and international relations: The rise of China and its effects. International Studies Perspectives, 7.

- Ryan R.M., O’Toole C.M., McCann F. (2014). Does bank market power affect SME financing constraints? Journal of Banking & Finance, 49, 495–505.

- Sapir J. (2000). Le consensus de Washington et la transition en Russie: histoire d'un échec. Revue Internationale de Sciences Sociales, 166, 541–553.

- Sapir J. (2008). Le Nouveau XXIè Siècle. Paris: le Seuil.

- Sapir J. (2009). The social roots of the financial crisis: Implications for Europe. In: Degryze C. (Ed.). Social Developments in the European Union:2008. Bruxelles: ETUI.

- Sapir J. (2011). La Démondialisation. Paris: Le Seuil; reprinted in an augmented version (2021). Paris: Le Seuil.

- Sapir J. (2021). Is eurozone accumulating an historic lag toward Asia in the Covid-19 context? Economic Revival of Russia,1(67), 89–102.

- Sapir J. (2021). The economic shock of the health crisis in 2020: Comparing the scale of governments support. Studies on Russian Economic Development, 32(6), 579–592.

- Sapir J. (2022). Is economic planning our future? Studies on Russian Economic Development, 33(6), 583–597. DOI: 10.1134/S1075700722060120

- Sapir J. (2023). Wendet sich der Wirtschaftskrieg gegen Russland gegen seine Initiatoren? In: Luft S., Kostner S. (Eds.). Ukrainekrieg. Warum Europa eine neue Entspannungspolitik braucht. Frankfurt am Main: Westend-Verlag.

- Shirov A.A. (2023). Development of the Russian Economy in the medium term: risks and opportunities. Studies on Russian Economic Development, 34(2), 159–166.

- Steill B. (2013). The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order. Princeton, N-J.: Princeton University Press.

- Stokes B. The world needs an economic NATO. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/05/17/ukraine-war-russia-sanctions-economic-nato-g7/

- Struye de Swielande T. (2008). Les États-Unis et le nouvel ordre mondial emergent. Les Cahiers du RMES, 5(1).

- Subramanian A., Wei S-J. (2007). The WTO promotes trade, strongly but unevenly. Journal of International Economics, 72(1), 151–175.

- Swaine M.D., Tellis A.J. (2000). Interpreting China’s Grand Strategy: Past, Present, and Future. Santa Monica: RAND.

- Tartakowsky D. (2019). Les Gilets jaunes, les mouvements sociaux et l’État L'ENA hors les murs, 494(2), 9–10. Available at: https://www.cairn.info/revue-l-ena-hors-les-murs-2019-2-page-9.htm

- Védrine H. (2000). Les Cartes de la France à l’heure de la mondialisation. Paris: Fayard.

- Wang Y.-K. (2006). China’s Grand Strategy and U.S. Primacy: Is China Balancing American Power? Washington: CNAPS, Brookings.