A comparative analysis of structural and developmental trends at major Cheptsa fortified sites in the Western Urals (Idnakar, Uchkakar, and Guryakar)

Автор: Zhurbin I.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.48, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145469

IDR: 145145469 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2020.48.1.120-128

Текст статьи A comparative analysis of structural and developmental trends at major Cheptsa fortified sites in the Western Urals (Idnakar, Uchkakar, and Guryakar)

In the western Urals, the upper and middle reaches of the Cheptsa River represent a unique archaeological region. Over 300 archaeological sites are currently known there. Most of them belong to two chronologically and genetically related cultures, namely the Polom (late 5th to early 9th centuries AD) and Cheptsa (late 9th to early 13th centuries) cultures (Arkheologicheskaya karta…, 2004: 46–64). According to updated data, 143 sites can be attributed to the latter. These sites are distributed over the northern portion of the modern Udmurt Republic.

Fortified settlements are located along the banks of the Cheptsa and its tributaries: on promontories between the river and creek, the river and ravine, or near the creek between ravines. Topographic features of the promontories predetermined the uniform structure of the fortifications, consisting of one or several lines of ramparts and ditches, which protected the ground from the external part of the settlement. Cheptsa fortified settlements differ significantly in terms of size, structure, and thickness of their cultural layers. They probably played different roles during the Middle Ages (Ivanova, 1998: 217–224). We will examine three major fortified settlements––Idnakar,

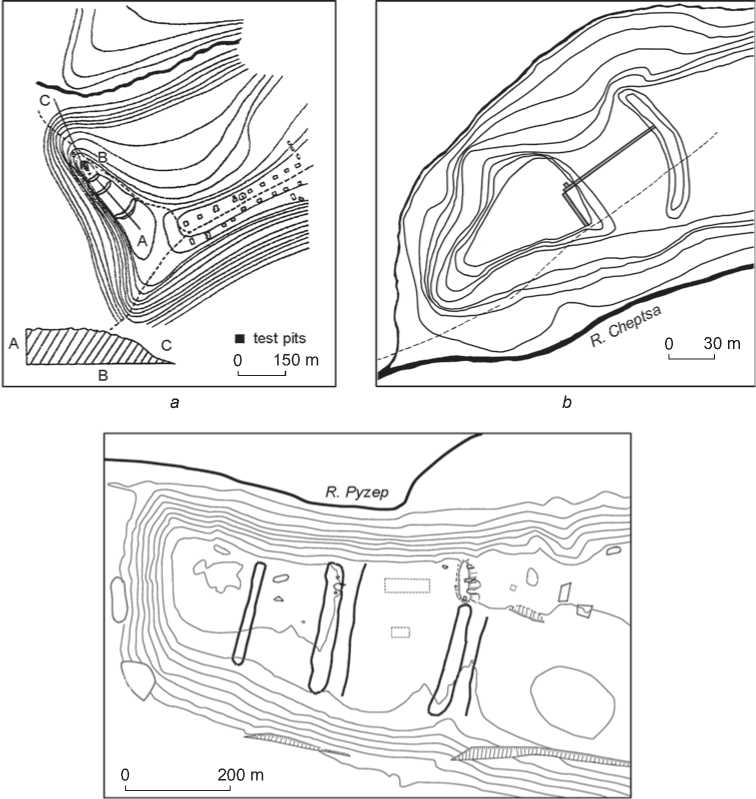

Fig. 1. Location of Cheptsa settlements.

1 – fortified; 2 – unfortified.

Uchkakar, and Guryakar––as key medieval centers in the Cheptsa River basin (Fig. 1).

To assess the general trends and features of their structure and planning, a geophysical survey was carried out, using electrical and magnetic prospecting methods. By correlating geophysical anomalies with excavation findings, two interrelated tasks were completed: reconstructing past events on the basis of archaeological evidence, and assessing the reliability of the geophysical findings.

Idnakar fortified settlement

Soldyr I Idnakar settlement is located 2 km west of Soldyr village, in the Glazovsky District of the Udmurt Republic. It currently falls within the boundaries of the town of Glazov. The settlement occupies a large promontory of a high bedrock river terrace formed by the Cheptsa and its right tributary Pyzep River. In the east, from the unprotected external part of the site, two large ramparts are visible. The outer rampart delimits the ground, while the medial one divides it into two roughly equal portions (Fig. 2, c ). S.G. Matveev, who excavated the site in 1927 and 1928, recorded the inner line of fortification, invisible in the landscape. The outlines of the inner fortifications were reconstructed on the basis of geophysical data.

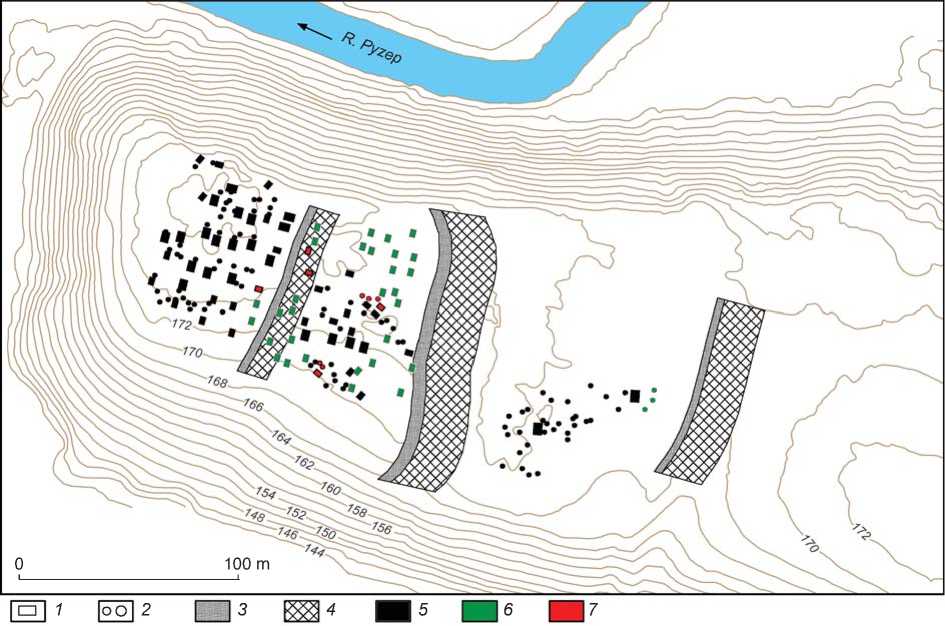

Idnakar was mentioned in records of the 17th century. A.A. Spitsyn (1893: 73–74) and N.G. Pervukhin (1896: 66–70) were the first who described it as an archaeological site. In 1927 and 1928, S.G. Matveev conducted there large-scale excavations, using the method of mutually perpendicular trenches; however, the results of the study were not published. Since 1974, the site has been excavated by the archaeological team from the Udmurt Institute of History, Language, and Literature of the Ural Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences (Izhevsk), supervised by M.G. Ivanova. As a result, all structural elements of the settlements (inner, medial, and outer) and fortification lines were examined (Fig. 3).

Geophysical prospection has been carried out in parallel with excavations, starting from 1992. Resistivity survey and electrical resistivity tomography were conducted in the areas where no excavations were planned: primarily, in the site’s northern and southern peripheries (Ivanova, Zhurbin, 2006: 72–74), and then along all three fortification lines (Ivanova, Zhurbin, Kirillov, 2013). In some places, archaeological excavation crosschecked geophysical data (Fig. 3). Thus, almost the entire territory of Idnakar, excluding destroyed areas, was involved in interdisciplinary studies.

As comparative analysis of a variety of data has shown, the layout of the inner and medial parts of the settlement was close to linear. In most cases, long sides of rectangular buildings were oriented along the N-S line. In the outer part of the settlement, no evident regularity in locations of buildings can be observed.

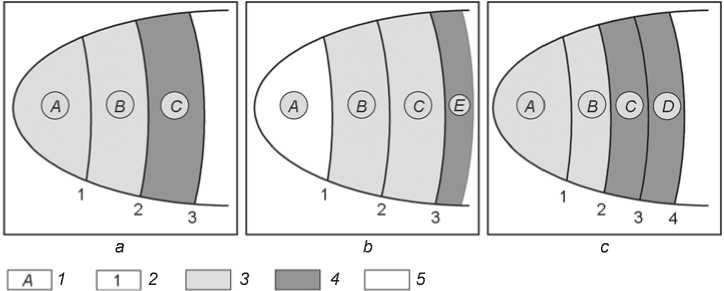

The main trends in the planning of the settlement were identified. In the inner and medial parts, predominantly residential and household buildings were situated (areas A and B ; Fig. 4, a ; Table 1). Dwellings were concentrated in the center of the settlement, while household and rare production structures were located along the southern and northern slopes of the promontory (Ivanova, 1998: 29–30). Later on, non-residential buildings were found in the area of the destroyed rampart and the ditch of the inner fortification line (Fig. 3; 4, a , line 1). According to archaeological data, from not later than the 11th century,

c

Fig. 2. Plans of the largest fortified settlements in the Cheptsa River basin.

a – Gordino I Guryakar of the 9th–13th centuries (Ivanova, 1998: Fig. 103, 1 ); b – Kushman Uchkakar of the 9th–13th centuries (Ivanova, 1998: Fig. 103, 4 ); c – Soldyr I Idnakar of the 9th–13th centuries (theodolite survey by V.I. Morozov, 1993; supplemented by A.N. Kirillov, 2009).

the rampart was flattened and the ditch was filled with clay removed from the top of the rampart (Ibid.: 20–22). After that, this area was actively used. Production structures associated with metalworking were unearthed there. In the boundary between the rampart and the ditch, a hearth and a pit attributable to the 11th century were found. In the outer part of Idnakar (area C ; see Fig. 4, a ; Table 1), the cultural layer has almost not been preserved—it was destroyed by long-term tillage. Excavation revealed primarily pits and bases of hearths. Most pits contained implements.

The analysis of changes in the layout of the site indicates common organizational principles. At the final stages of Idnakar use, household areas in the inner and medial parts were located along the slopes.

However, as the excavations have shown, household and production structures based immediately on the subsoil preceded dwellings in the medial part of the settlement. Consequently, before the outer defense line (line 3; see Fig. 4, a ) had been constructed, this area served as the household and production periphery of the settlement, which then was “shifted” to the outer part of Idnakar (Ibid.: 81).

Generally speaking, what we can observe at Idnakar is a gradual expansion of the settlement’s area. The boundaries of the “annexed” territory were determined by the new line of fortifications, while the area itself represented the household-production periphery of the settlement. No cultural layer has been recorded outside the outer defense line.

Fig. 3 . Structure and layout of Idnakar.

1 – clay platforms; 2 – utility pits; 3 – rampart; 4 – ditch; 5 – features revealed by excavations; 6 – features revealed by geophysical methods; 7 – features revealed by geophysical methods and confirmed by excavations.

Fig. 4 . Schematic representation of the structural and housing trends of the settlements. a – Idnakar; b – Uchkakar; c – Guryakar.

1 – designation of structural parts; 2 – fortification lines; 3 – residential and household zone; 4 – household and production zone; 5 – housing strategy unidentified.

Uchkakar fortified settlement

Kushman Uchkakar settlement is the westernmost site of the Cheptsa culture (Fig. 1). It is located on the promontory formed by the river bank and a deep valley of a creek (Fig. 2, b ). The surface of the site is even, densely covered with turf and high grasses. Two defense lines are visible on the ground (Arkheologicheskaya karta…, 2004:

200–203). The settlement was first mentioned in records from the 17th century. In the early 1880s, Spitsyn examined the site, and in the middle of the same decade, Pervukhin conducted there pilot excavations, made a topographic plan, and bought a large collection of finds from local peasants. In 1930, A.P. Smirnov conducted studies at the settlement and made two mutually perpendicular trenches through the inner ground near the ditch and through the

Table 1 . Housing trends of the settlements

|

Settlement |

Structural parts |

||||

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

|

|

Idnakar |

Residential and household |

Residential and household |

Household and production |

– |

Not found |

|

Uchkakar |

Unidentified |

" |

Residential and household |

– |

Household and production |

|

Guryakar |

Residential and household |

" |

Household and production |

Household and production |

Not found |

outer part of Uchkakar (Fig. 2, b ). Twenty constructions were unearthed, including dwellings, storehouses, hearths, furnaces, sheds, and pinfolds. Of especial interest were bloomeries, which were further mentioned by different researchers, including B.A. Kolchin (1953: 30–37). The findings remained long undescribed. On the initiative of Smirnov, they were introduced into scientific use and dated to the 9th–12th centuries, possibly to the first half of the 13th century (Ivanova, 1976).

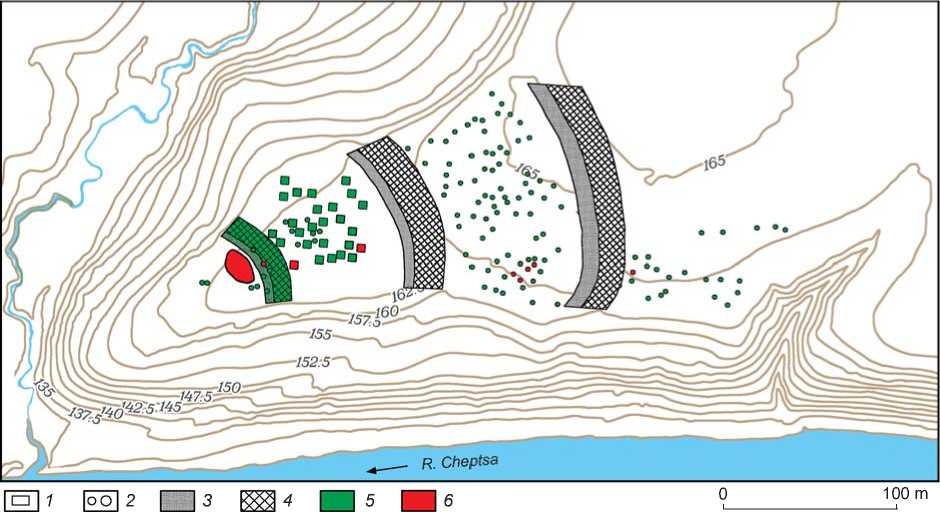

Systematic investigation of Uchkakar began in 2011. The interdisciplinary research strategy differed from that used in the study of Idnakar. A geophysical survey was conducted throughout the entire territory of the settlement prior to the excavations (Zhurbin, Ivanova, 2018). This provided a preliminary idea about the structure and layout of the settlement. Then, residential and household structures, utility and production pits, and the inner fortification line were systematically excavated (Fig. 5). In all structural elements of Uchkakar, various layout features were revealed. The subsequent comparison of findings from the excavation (relating to less than 2 % of the site area) to the combined map of geophysical anomalies has enabled us to assess the settlement’s layout and to reconstruct its plan. In addition, the thickness of the cultural layer and its state of preservation were assessed. For the first time at Cheptsa settlements, an unprotected external part of the settlement was discovered (area E ; Fig. 4, b ; Table 1).

The structure of Uchkakar turned to be more complicated than would be imagined from the visible topographic features. The geophysical survey revealed the inner fortification line invisible in the landscape. Excavations supported this finding (Modin, Zhurbin, Ivanova, 2018). As a result, four structural parts of the settlement were identified (see Fig. 4, b ; Table 1): the inner (area A , delimited by fortification line 1, evened in the past); medial and outer (areas B and C , delimited by fortification lines 2 and 3, visible in the landscape); and the unprotected external part (area E outside outer fortification line 3).

The layouts and general trends in construction of the medial and outer parts of Uchkakar (areas B and C ; see

Fig. 4, b ; Table 1) are similar to those of the inner and medial parts of Idnakar (areas A and B ; see Fig. 4, a ; Table 1). The buildings were arranged in irregular rows. In area C, the cultural layer had been almost destroyed by long-term tillage. Only deepened features (about 80 pits) have been preserved (Fig. 5). Excavations confirmed the presence of dwellings in the central part of area B (which had previously been detected by geophysical methods), and the presence of deepened household structures of sophisticated construction in area C , near the southern slope of the promontory. An identified hearth with a pit could have been used both for heating and for some production purposes (Ivanova, Modin, 2015). The data obtained agree with the results of excavations conducted by Smirnov (Ivanova, 1976). Most buildings revealed by him are residential or household structures (see above). Regrettably, the plans of these excavations have not been preserved. However, since the largest portion of the trench was located in the central part of the outer area of the settlement (Fig. 2, b ), the provided data agree with the hypothesis that area C was occupied mostly by residential and household structures.

In the unprotected external part of Uchkakar (area E ; see Fig. 4, b ; Table 1), chaotically located deepened features were recorded. Most of these correlate with bipolar anomalies on the magnetogram, possibly evidencing the pyrogenic infill of the pits (Skakun, Tarasov, 2000; Fedorina, Krasnikova, Mesnyankina, 2008). Excavations conducted in the area of such an anomaly have shown that it resulted from a deepened production structure of a sophisticated configuration (see Fig. 5). Chaotically located smaller depressions (possibly, utility pits) were also found. This situation agrees with the regularities of planning observed in the outer part of Idnakar (area C ; see Fig. 3; 4, a ). The principal difference of Uchkakar is the well-developed household-production periphery, located outside the protected part of the settlement.

Another distinctive feature of Uchkakar is the fragmentary layout of its inner part (area A ; see Fig. 4, b ; Table 1). This is located on the spit of the promontory and limited by the fortification line, invisible in the landscape

Fig. 5 . Structure and layout of Uchkakar.

1 – clay platforms; 2 – utility pits; 3 – rampart; 4 – ditch; 5 – features revealed by geophysical methods; 6 – features confirmed by excavations.

(line 1; see Fig. 4, b ). The cultural layer is nearly absent in this area. Geophysical survey revealed only some features deepened into subsoil: an ellipsoidal hollow measuring 12 × 20 m and several chaotically located pits 1–2 m in diameter (see Fig. 5). As excavations have shown, the hollow represents a compact group of surface and deepened household structures of a sophisticated configuration (Mezhdistsiplinarnye issledovaniya…, 2018: 63–69). Certain non-contemporaneous structures partly overlap. In addition, several specific features were found. These are stone pavements without traces of thermal impact. They have no parallels at Cheptsa settlements. The unusual layout of this part of Uchkakar and the peculiarities of the revealed features prevent us from reconstructing the housing scheme.

In general, gradual expansion of the settlement can be traced at Uchkakar. New lines of fortifications delimit the “annexed” territory occupied by residential and household structures. The presence of the unprotected external part of the settlement (household-production periphery) and the absence of the dense housing zone in its promontory part constitute significant differences between Uchkakar and other known sites of the Cheptsa culture.

Guryakar fortified settlement

Gordino I Guryakar settlement is located in the eastern part of the Cheptsa cultural area (see Fig. 1). It was first mentioned in records from the 17th century. Despite the relevance of Guryakar to the Cheptsa culture and to the medieval history of Finno-Ugric peoples in general, very little is known about that site. It was examined by N.G. Pervukhin in the 1880s, A.P. Smirnov in 1894, and T.I. Ostanina in 1991. In 1957, V.A. Semenov made a topographic plan of the settlement and dug two test pits (Arkheologicheskaya karta…, 2004: 119–120). In 1979, M.G. Ivanova (1982) conducted the first (and the only) large-scale excavations there. The excavated area, measuring 288 m2, was situated in the promontory part of the settlement. As at other Cheptsa sites (Ivanova, Zhurbin, 2006: Fig. 3), the central element of the dwellings was a subrectangular platform made of compacted or burnt clay. Dwellings contained utility pits and hearths. A deep pit measuring 12–16 m2, with steep walls, normally adjoined the platform. Such a pit was filled with heterogeneous humified material with stones, ceramic fragments, coals, fired soil, and decayed organic matter. At Guryakar, most clay platforms are oriented along the NE-SW line. During the interpretation of geophysical data, the combination of these characteristics has made it possible to delimit the complexes of dwellings.

Guryakar occupies a promontory of a high bedrock terrace (Fig. 2, a ), which is typical of the Cheptsa medieval fortified settlements. From the sloping side of the promontory, the settlement’s ground is delimited by fortifications. It was previously believed that there were three defense lines at Guryakar. At present, these are hardly visible in the landscape because of longterm tillage. Interdisciplinary studies revealed another

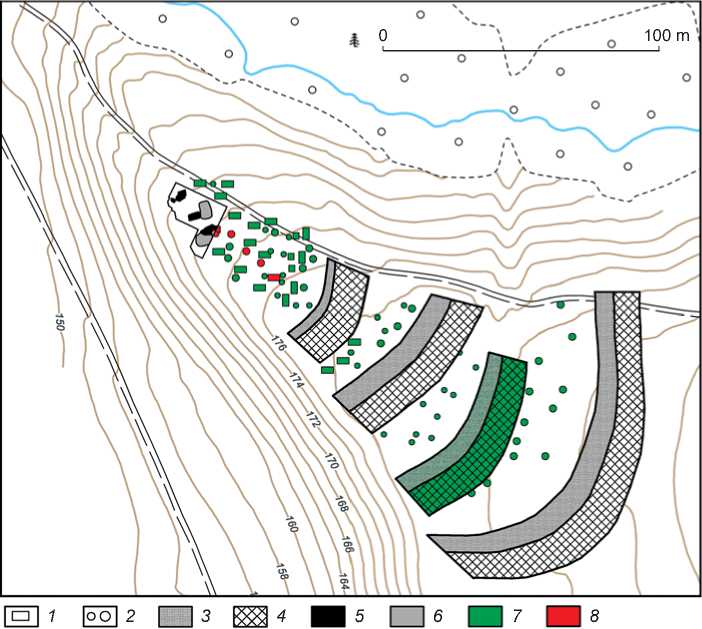

Fig. 6 . Structure and layout of Guryakar.

1 – clay platforms; 2 – utility pits; 3 – rampart; 4 – ditch; 5 , 6 – clay platforms ( 5 ) and utility pits ( 6 ) revealed by excavations; 7 – features revealed by geophysical methods; 8 – features revealed by geophysical methods and confirmed by excavations or soil boring.

fortification line located between the previously known second and third lines (line 3; see Fig. 4, c ; 6).

A geophysical survey (resistivity and magnetometry surveys, electrical resistivity tomography) was conducted throughout the entire territory of the settlement, including the area excavated by Ivanova. This provided additional clues for interpreting the totality of geophysical data. In the eastern part of the excavation, a deep pit with large stones (at a depth of 1.0 m from the level of recording) and a platform of burnt clay were partially unearthed (Ivanova, 1982: Fig. 5). The excavated area covers only part of these features. Their juxtaposition with geophysical anomalies adjoining this area has allowed us to correlate them. Such pits and platforms normally belong to residential complexes. Subsequent focused soil-boring revealed three other utility pits and a clay platform, as well as ramparts and ditches of all four fortification lines (Fig. 6).

Analysis of geophysical data and the results of soil boring has made it possible to assess characteristic features of the layout and general trends of the settlement’s planning. A dense zone of residential and household construction supposedly existed on the promontory part

(area A ; see Fig. 4, c ; Table 1). Three rows of structures, oriented along the promontory’s axial line, can be traced. Excavations revealed several other constructions (Fig. 6). In area B (see Fig. 4, c ; Table 1), buildings were arranged along the fortifications. Obviously, there were not only residential, but also production structures: a group of large pits with pyrogenic infill was recorded along the inner border of fortification line 2 (see Fig. 4, c ; 6). In areas C and D (see Fig. 4, c ), no clay platforms were found. In these areas, mostly pits filled with fire-affected soil are present (see Fig. 6). These features were probably associated with household or production activities. They were also located along the defense constructions.

In contrast to Idnakar and Uchkakar, the residential area at Guryakar remained within the boundaries of the protected part (area A and, possibly, B ), despite repeated expansions of the territory. In areas C and D , the geophysical survey revealed some deepened features supposedly associated with fire-hazardous production activities. As at Idnakar (in contrast to Uchkakar), the unprotected external part of the settlement was not identified.

Table 2 . Parameters of structural parts of the settlements

|

Settlement |

Number of fortification lines |

Distance between fortification lines, m |

Housing area increase (times) at different stages |

Initial / total housing area, m2 |

|

Idnakar |

3 |

1 and 2 – 60 |

2 |

6150 / 26,300 |

|

2 and 3 – 100 |

2.1 |

|||

|

Uchkakar |

3 |

1 and 2 – 65 |

3.8 |

2250 / 21,800 |

|

2 and 3 – 80 |

2.2 |

|||

|

Guryakar |

4 |

1 and 2 – 15 |

1.5 |

2400 / 7400 |

|

2 and 3 – 25 |

1.3 |

|||

|

3 and 4 – 25 |

1.6 |

Conclusions

Interdisciplinary studies at the three largest fortified settlements of the Cheptsa culture (Idnakar, Uchkakar, and Guryakar) have made it possible to assess their boundaries, structure, and layouts. At each site, a specific research strategy was used. The reconstruction of Idnakar was based on a comparative analysis of findings from large-scale excavations and from geophysical surveys. At Uchkakar, pilot excavations of separate features were carried out using the map of geophysical anomalies, spanning the entire site area. At Guryakar, the structure and layout were assessed by a comparison of the totality of various geophysical data with the results of focused soil boring and earlier excavations. In all cases, the extrapolation of geophysical findings ensured a high accuracy for the archaeological reconstruction.

Various approaches combining geophysics with archaeology revealed previously undetected fortifications (cf. Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, 5, 6), and also shed light on the layout and housing trends of each structural part of these Cheptsa settlements, which were similar in appearance, but different in essence (see Fig. 4; Table 1). At Idnakar and Guryakar, the “annexed” territory, protected by a new line of fortifications, was used as a household-production periphery. At Uchkakar, this territory was used mainly for residential and household construction, whereas the household-production zone was located in the unprotected external part of the settlement. Another important difference at Uchkakar is the absence of residential, household or production zones on the promontory part, which were typical of Cheptsa settlements.

Interdisciplinary studies also allowed the dynamics of Idnakar’s, Uchkakar’s, and Guryakar’s development to be assessed (see Fig. 4; Table 2). Notably, the table indicates the net surface area of the settlements’ parts: those which could have been used for residential, household, or production structures (excluding the territory occupied by ramparts and ditches). These data clearly demonstrate the differences in expansion of the habitable territories. New fortification lines at Idnakar and Uchkakar (see Fig. 3

and 5) increased the settlements’ area at least twofold. The “annexed” territory was intensely used as a residential and household zone. Both excavations and the geophysical survey show dense housing there. Thus, at Idnakar and Uchkakar, the construction of another fortification line, defending a newly developed territory, can be regarded as evidence of a new stage in the evolution of the settlements. At Guryakar, the width of the “annexed” territory does not exceed 25 m (see Fig. 6), and the size of the protected territory increases by half at most (Table 2). It can be tentatively proposed that at this settlement, an indepth fortification system was created, without expanding the site’s area.

Interdisciplinary studies provided rich information for a comparative analysis of the structure and layout of all three key fortified settlements of the Cheptsa culture Despite their external similarity (topographic characteristics, large area, thick habitation layer, several fortification lines, etc.), Idnakar, Uchkakar, and Guryakar show substantial differences in structural and housing trends.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Project No. 18-49-180007 p-a).