A comparative perspective of educational policies of the Netherlands in Indonesia and Great Britain in Malaya during the 19th and 20th centuries

Автор: Hiep T.X., Phuc N.H., Kiet Le.H., Binh N.T., Tho T.T.

Журнал: Вестник Новосибирского государственного университета. Серия: История, филология @historyphilology

Рубрика: Всеобщая история

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.24, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This paper comparatively examines the educational policies of the Netherlands in Indonesia and Britain in Malaya during the 19th - 20th centuries from the perspective of post-colonial theory. By using historical documents and synthesizing existing literature, the study reveals similarities and differences in their approaches. Notably, both implemented a “dual education” system, separating indigenous and Western-oriented education tracks, while adopting secular curricula and centralized administration. The Dutch were more flexible in language policies, whereas the British enforced stricter linguistic segregation. Influenced by the “divide and rule” strategy, segregated school systems for each ethnic group emerged, fostering communal divides. However, these policies inadvertently facilitated modernization, mass education, and female literacy. Moreover, they unintentionally nurtured an intellectual class that catalyzed nationalist movements. While serving colonial interests, the educational reforms laid foundations for modern, diversified education systems in post-colonial Indonesia and Malaysia. The paper contributes insights into colonial legacies and their complex ramifications on Southeast Asian societies development trajectories. It underscores how education served as a double-edged sword, both consolidating colonial rule and sparking movements towards independence and progress.

Colonial education, native malay community, indonesian community, british colonial government, dutch colonial government

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147247134

IDR: 147247134 | УДК: 94(594)+94(595) | DOI: 10.25205/1818-7919-2025-24-1-65-81

Текст научной статьи A comparative perspective of educational policies of the Netherlands in Indonesia and Great Britain in Malaya during the 19th and 20th centuries

After occupying the colonies, what both Dutch and British wished for was political stability, with qualified personnel who could be loyal to, obey and had gratitude with the colonial governments. In that consideration, all plans to propagate Western religion and civilization would face hassles when educational policies could not grow their roots in the native lands. Along with the invading troops, all the wishes above went to educational foundations built up by the Dutch and British educators. When talking about the roles of education in occupying the colonies, Georges Hardy, a theorist of colonial education emphasized: “We also wanted to grasp native people’s hearts and erase all misunderstanding among us… Appreciating their lands and helping them cling to our cause were the targets of the spiritual conquer. This invasion was longer lasting and brighter than prior, but was ample and hence, needed praising. No other tools might be able to help but the schools…” [Phuong, 2020, p. 31]. Besides, through educational policies, colonial government could gain control of native people’s ideology.

Until the end of the 19th century, after prevailing all over the Malay peninsula, British colonial government applied suitable education patterns for each ethnic community. In the meantime, in Indonesia, the Dutch colonial government also implemented various educational revolutions so as to support their governing and calm down international opposing views against their exploit policies on the new land. Both Dutch education in Indonesia and British education in Malaya reflected basic innovations of the mother countries during the time. This study employs a multi-method approach, combining historical research methods with logical analysis, synthesis, and comparative techniques, situated within the theoretical framework of postcolonial theory, the authors would like to go into deep analysis of each educational policy that Dutch and British colonial governments employed in Indonesia and Malaya, as well as come to the resemblances and dissimilarities between them.

To fully contextualize the educational policies implemented by colonial powers in Southeast Asia, it is crucial to understand how they conceptualized the role and function of education differently in their colonies as opposed to their home countries. In Britain and the Netherlands, education was seen as a vehicle for social mobility, intellectual advancement, and national development [Phuc, 2018; Van, 2011]. However, in their colonies, the perspective shifted dramatically. Colonial administrations primarily viewed education as a means of maintaining control, creating a class of subordinate civil servants, and fostering allegiance to the empire [Suratminto, 2013].

While education in the metropole was aimed at producing knowledgeable citizens and future leaders, colonial education was deliberately limited in scope and access. It sought to create a small educated elite who could serve as intermediaries between the colonizers and the colonized masses, while simultaneously preventing the spread of ideas that might challenge colonial rule. This stark contrast in educational philosophy – empowerment at home versus control abroad – laid the foundation for the establishment of parallel and often discriminatory educational systems in the colonies. Understanding this fundamental difference in perspective is essential for comprehending the motivations and repercussions of colonial educational policies in Indonesia and Malaya.

Postcolonial theory provides new concepts and perspectives to evaluate the cultural, political, economic, and social legacies left by imperial powers in former colonies. According to this theory, colonial powers employed strategies such as “divide and rule”, racial and class-based discrimination to maintain their dominance. However, the processes of invasion and colonial rule also inadvertently catalyzed social changes, contradictions, and subsequent liberation movements [Azim, 2008, p. 236].

In the context of researching the educational policies of the Netherlands and Britain in Indonesia and Malaya, postcolonial theory helps identify the strategies employed by colonial government in establishing parallel education systems to divide and control different ethnic communities. Simultaneously, it allows for an assessment of the complex impacts of these policies – both consolidating colonial rule but also facilitating the modernization process and laying foundations for later educational development.

Based on this theoretical framework, the study utilizes historical research methods to examine primary and secondary sources related to the educational policies and practices implemented by the Dutch and British colonial authorities. The logical analysis method is employed to systematically evaluate the rationales, objectives, and implications of the adopted educational policies. The synthesis method helps integrate information from various sources to construct a comprehensive overview of the educational landscape during this period. Finally, the comparative method allows for juxtaposing and identifying similarities and differences in the educational policies of the Netherlands and Britain, as well as analyzing the unique contextual factors that influenced policy formulation and implementation.

By combining these complementary methodological approaches and the postcolonial theoretical framework, the study aims to provide a multidimensional and in-depth understanding of colonial educational policies, their underlying motivations, and their complex impacts on the socio-political contexts of Indonesia and Malaya during the period under investigation.

After Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) was broke off and dissolved in 1799, Dutch government started their direct control over Colonial Indonesia. Under the reign of Dutch Government, Indonesian education was executed and managed directly by the colonial government in order to universalize Dutch culture. However, it could be said that the foremost objective of the educational policies that the Netherland “implemented in Indonesia did not aim at civilizing the indigenous people here, not at developing Indonesia as well. The main target of the education that the colonial government was conducting on this isle was to train a staff of agents for their exploitation in and control over the colonial states” [Phuc, 2018]. Therefore, the educational policies with that aim belonged to a system of policies for “Divide and Conquer”, and “Unite and Conquer” of the colonial government, so as to maintain the benefits of Dutch people and partly helped to limit the objection of native people.

At first, Dutch government only founded schools “to educate children from Western families, half-blooded, and a very small number of young people from native, high-class origins” [Khanh, 2012, p. 247]. Their schools were generally erected in the quarters of Western people or residential areas of high-class Indonesian, established by Dutch government or Churchmen. Indigenous low-class people and farmers could go to Islam’s schools of Pasentren1, or had home schooling.

Nevertheless, under the influence of liberal politics, which was developing and had big impact throughout Europe, educational policies for colonial areas, including Indonesia, gained more priority. Especially in 1871, the Dutch governor issued an Educational Decree, which emphasized the construction of public education in Java and other islands in Indonesia. Also starting at this time, when the new Educational Law Suit was published, Westernized Primary Schools expanded their admission for different categories of children. Besides, also in accordance with this rule, teacher training got more focus and many public primary schools were built in different areas. “The number of public primary schools were expanded in Java and Madura, a rise from 82 schools in 1873 to 193 ones in 1883, and in all other islands from 117 schools to 284 schools” [Suwignyo, 2012, p. 52].

As regarded the demand of governing the colony, the Dutch – since the late 1890s – were more concerned with constructing a schooling system. “Until 1893, the Dutch only opened two systems of schools specializing for indigenous people; one was Local First-ranked Schools for children from noble families and mandarins (Priyayi), and the other was local, second-ranked schools to provide basic education for children from different social classes, mainly poor urban and rural commoners” [Khanh, 2012, p. 247]. This can be considered an important key point and an education reform that the Netherland performed to meet the need of controlling and developing education in Indonesia. Concerning this issue, Agus Suwignyo evaluated: “1893’s Educational reform pathed the way for Indonesian children, instructing the people to be educated in Western patterns, and partly helped expand opportunities for learning in a wider range for Indonesians” [Suwignyo, 2012, p. 53]. The curricula of two schools were: First-ranked would provide such subjects as mathematics, Indonesia geography, Indonesia history, arts and geomatics; while children of Second-ranked institutes only learned how to read and write in their native languages, and geomatics; besides, they could also take one of the other subjects taught in First-ranked schools. At first, Dutch language was not taught, only native or Malay languages were employed in teaching and learning. Until 1907, the Dutch language was introduced as a subject. Accordingly, school age for primary level was stipulated to be between 6 and 17 years of age.

Another crucial milestone to mark the development of Indonesian education was the publication of “Innovative Line” for Colonial Indonesia by the Dutch Queen in 1901. “In real nature, those phi- losophies confirmed that an empire’s governing should be win-win; it is not recommended to consider the colonies as a source of profits; and a country’s strength is a common, better commitment, education, benefit for native people; and above all, help them approach Western cultures, ideologies and technology” [Christie, 2000, p. 29–30]. Accordingly, native people would gradually be able to self-govern and have equal rights in approaching promotion chances in their work. In order to carry out these missions, the colonial government constructed people’s banks, provided many forms of budgets to support people, focused on medical investment and expanded the educational and training system. It can be assured that these were improved activities and “at the same time minimized the conflicts between Indonesian people and Colonist Netherland” [Tong, 1992, p. 43].

Accordingly, the number of vocational programs for graduated students from primary schools were more focused. Also from the year 1901, the Dutch commenced establishing a system of college and university education in public sector, especially in the majors of agriculture and law. This can be seen as the second educational reform of the Dutch colonial government implemented in Indonesia. In 1903, the first School of Agriculture was constructed in Indonesia. By the year 1907, The School of Veterinary Medicine had been built, followed by the School of Law in 1908. Then came the Business School (1915) and School of Agriculture Education (1917). To support the teaching and training, the colonial government also erected buildings for labs, which were equipped with necessary educational aids for those schools; however, the quantity was not sufficient. Nonetheless, the lack of budget, especially in the economic crisis (1929–1936), led to hardship for the schools’ performance. In the meantime, due to the absence of career support of the colonial government, many students went unemployed after graduation.

A prominent point in the educational policies of the Netherland in 1907 was when Governor Van Huezt initiated the foundation of Village Schools (Desa school). “Each or several villages constructed a school, usually from the free materials provided by the government, and contributed an annual amount of 90 guiders for maintenance” [Hall, 1997, p. 1081]. The colonial government would provide teachers and course books for education. In some Village Schools, parents had to pay tuition fees, but generally they were free for the whole 3 school years with local tongues as teaching languages. The aim of Village Schools was to eliminate illiteracy among rural children, as the subjects were merely reading, writing and calculating. With the efforts of the colonial government, the number of Village Schools for boys and girls went up annually (see table 1).

Number of Village Schools and pupils in Java and Madura

Table 1

|

Year |

School number |

Pupil Number |

|

|

Male |

Female |

||

|

1910 |

1,161 |

66,125 |

5,114 |

|

1911 |

1,740 |

99,757 |

7,295 |

|

1912 |

2,531 |

157,048 |

9,917 |

|

1913 |

2,948 |

187,046 |

12,670 |

|

1914 |

3,521 |

223,450 |

15,965 |

|

1915 |

3,696 |

242,436 |

18,691 |

|

1916 |

4,006 |

269,458 |

24,413 |

|

1917 |

4,185 |

274,113 |

25,403 |

|

1918 |

4,473 |

270,551 |

26,331 |

Source: [Penders, 1968, p. 100].

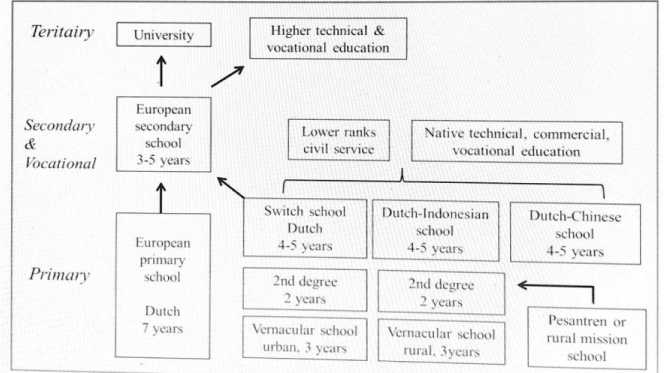

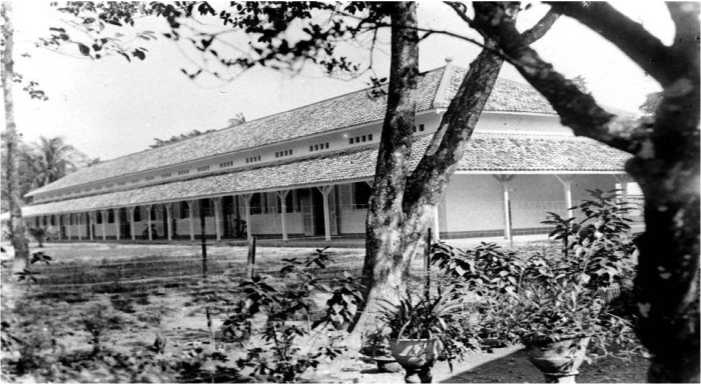

Another noted point, and also a common feature in comparison to British educational policies in Malaya, was that the Dutch government established the “dual education” policy in Indonesia, in which the Netherland allowed native education and Westernized education to be run in parallel (see fig. 1). This favoured the maintenance of traditional education, and afterwards, thanks to the contact with Western education, natural science subjects were introduced in to the curriculum of Mardasa, along with religion subjects in Islam’s school system. When European Primary Schools (Europesche Lagere School – ELS) (see fig. 2), Hollander-Chinese School (Hollandsch Chineesche School – HCS), Holladsch Inlandsche School – HIS were converted from First-ranked schools since 1914, Hogere Burger School – HBS, Meer Uitgebreid Lager Onderwijs (MULO) and Algemeen Middelbare School – AMS, along with other colleges and universities were categorized into Western-oriented educational system. The distinctive point between these two educational systems was that the Western-oriented educational system had all education levels from primary, secondary to college and university, with better educational environment, in comparison to Local Education. With this difference, the colonial government, unintentionally, created a new inequality among learners after graduation, “with the same qualifications, in the same major, even with more qualified academic results, the promotional routes of native people were always harder. In addition, there existed ethnic discrimination in payment. In the same job, native Indonesians were forced to accept lower salary than their Dutch or European-Asian half-blooded colleagues” [Khanh, 2012, p. 248].

Fig. 1. Educational System in Indonesia under Dutch colony. Source: [Frankema, 2013, p. 314]

Fig. 2. Hollandsch Chineesche School. Source: Indonesia National Archives

In the meantime, the colonial government also sent many Indonesian students to the Netherland for training. This oversea study formed an intellectual class with Western education in Indonesian society at the beginning of the 20th century. Thank to attending schools in the Netherland, some Indonesian people had chances to approach Western democratic ideology. It was these people who became the key persons in Indonesia’s revolutions for people’s liberation in the years 1920–40s, and in the fights against Japan’s conquers in 20th century.

Along with consolidating the administrative and law regime, as well as exploiting the colony economically, the British government advocated in strengthening the promulgating of Western – British-oriented – education and lifestyle in Malaya. Through education, promulgation and assimilation in culture can be performed as one of the main aims of the Great Britain’s colonists. In colonial Malaya, as well as Mianmar, India and others, the Great Britain carried out their viewpoint that said “educational policies had to be constructed so as to be adaptive to each ethnic group and suitable for political roles, as well as unique economic position of each group in colonial social structure” [Van, 2011]. With that objective, educational policies were implemented by the colonial government in the policy system of “Divide and Conquer”, so as to prevent the ethnic groups of Malay, Chinese and Indian from uniting to oppose the British people, and consolidate their political positions in the colonies.

With the aim of maintaining their position in Colonial Malaya, besides political-economical tactics, the Great Britain employed education as an effective tool for their “Divide and Conquer” policy. With that interference, the British government used educational policies to separate the Native Malay communities from Indian, Chinese Immigrant communities in different states of Malaya. In order to be adaptive to each group, Malaya’s education was divided by the British government into 4 different school systems, namely British Schools, Malay Schools, Chinese Schools and Indian Schools, with respective teaching languages of English, Malay, Chinese and Tamil. With mother tongues as the educating languages, those schools were constructed for each particular ethnic group, and hence, learners obviously could not attend schools of other communities.

From the perspective of its real nature, maintaining different school systems emphasized the dissimilarities in ethnic’s histories and cultures, the factors that helped to protect the distinctive features of the ethnic groups in Malaya, China or India. The existence of these three school systems was originated from the demands for learning of the communities; and, in the meantime, could be considered as a way for the colonial government to easily implement their policy of “Divide and Conquer”. As a result, the only places for various ethnic communities to communicate, understand and respect each other were the English Schools, and thus, they can feel closer to English people. “The spoke English, dressed as Westerners, favoured English sports (including horse racing and gambling), and sent their sons to English Universities. Many of them became Britianized and lost the connection with their traditional culture” [Stevenson, 1975, p. 13–14].

In their educational policies, British government especially paid attention to implementing the policy of “dual education” for native Malaya community. To keep the original political roles and economical positions of the noble class as well as commoners in Malaya, British people founded and tried to carry out the policy of “dual education”. The system of “dual education”, or so-called “dualism in education”, means that British government maintained two paralleled educational systems, with local education on one side and Western-oriented education on the other side. Since the year 1876, budgets for education to support Chinese and Indian school were requested to cease, instead, British government commenced their investment into the dual education in English and Malay native language. Accordingly, the colonial government of the Great Britain would “implement an ‘elite’ educational program for the noble class and a ‘countryside-oriented’ educational program for commoners” [Van, 2011]. The target of this dual policy was “on the one hand, the colonial government gained the agreement from Malay’s noble class; and, on the other hand, limited the development of not only intellectuality but also economic power of people from lower social classes, and hence, prevented the political ‘awakening’ of this vast social force” [Van, 2011].

Constructing Malaya’s schools was a vital part in the “dual education” policy for native Malaya community. With the perspective of avoiding taking people away from their farms or making the commoners satisfied with their current state, an education full of “rural features” for holding farmers back was preferred by British people. Through the policies of British government, pupils from these schools would only be provided with elementary knowledge, which was sufficient for Malaya farmers to read, write, do calculation on the most basic ways, fundamental skills – such as gardening, fishing, handcraft techniques and knowledge of Malaya’s history and geography. For higher educational levels, the colonial government of the Great Britain gifted very few chances for Malaya farmers to contact. Consequently, if wishing to continue to higher education, Malaya students had to attend two-year particular switching classes specializing in English language. The main language for education in Malaya school was decided to be native Bahasa Melayu. However, British people implemented a plan to Latinize Malaya language and introduced Latin into schools, in parallel with native language. Evidently, native Malaya schools in this dual education policy robbed Malaya farmers’ children of their social promotional opportunities.

Regarding the noble class of Malaya, British government would grant them an “elite” education of British pattern to make them the future leaders, and, at the same time, complete their aim of “luring” the respect and loyalty of Malaya’s noble class through expanding their commitment in the new administrative units (see fig. 3). For the noble class of Malaya, they also recognized British education as a means for their children to achieve higher levels in the government; nonetheless, a majority of them still paid little interest in this so-called new innovative education. Due to that fact, British government implemented various policies to prioritize children from Malaya’s noble families, so as to improve this state of education. However, the results were not as expected by British people when “the total population of Malaya was 310.000, but only 2.636 people were employed at administrative offices of the government, in whom 1.175 were merely policemen” [Van, 2011]. To improve this reality, R. J. Wilkinson – after being appointed as School Inspector at Federal Malaya States (FMS) – carried out a new policy to found special schools that allow Malaya people from lower social classes to attend after gaining excellent academic achievement and being fluent in English.

Fig. 3. Malaya upper social class at Malaya College, 1906 Source: Malaysia National Archives

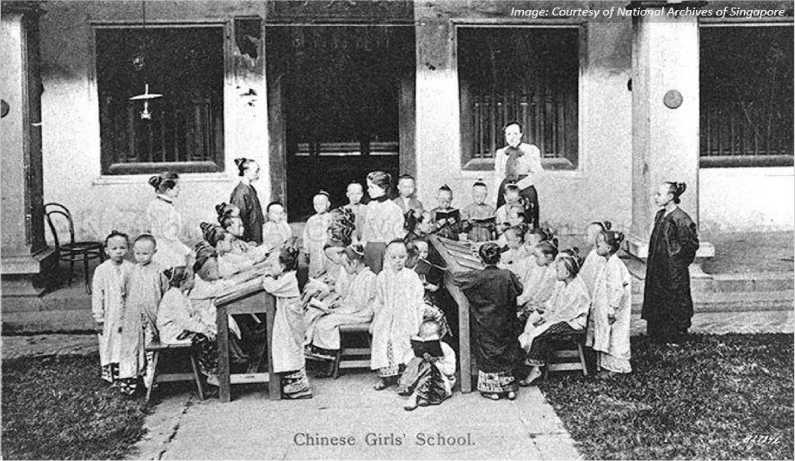

In regard to the community of Chinese immigrants (see fig. 4) and Indian Immigrants (see fig. 5), they could easily approach English schools, without any obstructions. It’s the reason why admission rates of Malayan people were always lower than those of Chinese and Indian people. “A 1924’s report pointed out that among the 32.873 students of English schools, there were about 90% learners from immigrant communities. Chinese students took the major part with more 61%, 14% went to Indians, while Asia-European half-blooded took 11%, although they occupied only 2% of the whole population” [Ozay, 2011].

Fig. 4. Chinese pupils in Chinese School for Girls Source: Malaysia National Archives

Fig. 5. Alsagoff Arabic School – founded in 1912 for pupils from Indian community in Indonesia.

Source:

To meet the demand in labor force and the performance of the policy “using native people to control native people”, British government increasingly built up a public educational system in English language from primary to university level for upper social classes of Malaya people. Raffles Institute – a public secondary school in British pattern was founded in 1873 in Singapore, two schools in new patterns were erected in Perak in 1878 and 1883, followed by Medicine University (1909), States Vocational College (1926), Successive Polytechnic College (1931). Since the 1920s, a system of libraries was built at various schools, especially in English ones, which was a considerate improvement in the infrastructure and effective support for the implementation of educational policies in colonial Malaya (see table 2).

Number of libraries in English Schools at Strait Settlement (1921–1932)

Table 2

|

1921 |

1926 |

1930 |

1932 |

|

|

Number of English schools |

40 |

45 |

50 |

54 |

|

Number of Schools with libraries |

15 |

27 |

37 |

39 |

|

Rate |

38 |

60 |

74 |

72 |

Source: [Han, 2009, p. 71].

Thank to many advantages in approaching education via English language, most of Chinese children were able to continue to join universities in Malaya or Great Britain after graduating from secondary schools. Therefore, Chinese people not only played the main role in developing modern economy of colonial Malaya but also were the community holding important positions in colonial government; meanwhile, native Malaya people rarely had chances to attend these schools.

It can be said that, with the interference of the “Divide and Conquer” policy of British people, an educational system with four school systems, as well as the “dual education” policy, was applied in Malaya, which resulted in thorough separation among the ethnic communities, or even within each community. Nonetheless, the presence of British people brought about changes in educational patterns in Malaya, which as outdated before. All these factors, all sectors of education in the period from 1816–1941 was so new to native Malaya people and a proof of education modernization.

Next, we would like to conduct a comparative analysis of educational policies: Dutch for Indonesian and British for native Malaya community.

First, a secular, modern and thorough educational content.

Throughout the conquering time of colonial government, Indonesia’s and Malaya’s education had big improvements, with fundamental and thorough changes in secular directions. Among them, the shift in education from religion education in western educational pattern could be seen as a prominent distinction in the secularization of education in Indonesia and Malaya. It can be said that secularizing education is a distinctive phenomenon of South-East Asia’s education in the current time and in reality, it was imported into South-East Asian countries in general, and in Malaya, Indonesia in specific, in colonial period.

Returning to the time before the 19th century, classes of Qur’an bible, Pesantren, Pondok were common traditional education in all villages of Indonesia and Malaya. The teaching and learning took place mainly at the churches of private houses of religious men in charge, and the main educational content was religion-related subjects. Therefore, in parallel with colonial exploitation, in many ways, Dutch and British colonists step-by-step converted those religious classes into secular educational institutes through transforming them into local schools.

The biggest advantage of the education of the Dutch and the British was that it brought about an innovative education for colonial nations with western influence, including centralized manage- ment, composing course books for different levels and subjects, focusing on practical and natural science. Obviously, the aim of founding secularized schools was to convert traditional classes of Qur’an bible in native villages. Although these classes were under the veil of religion, those cloaks gradually became faded and covered by secular coats. Under the management and control of the colonial government, local schools in Indonesia and Malaya were transformed deeply into secular educational institutes.

Besides the secularized educational programs, for the first time the Bahasa Melayu language of Indonesia and Malaya was Latinized into new written scripts and brought into teaching and learning at local schools to replace the complicated Jawa, which brought about advantages for educational acquisition. Another aspect expressing secular and modern direction was the foundation of modernized vocational and polytechnic schools in the early years of the 20th century. It can be said that this was the first time in Malaysia and Indonesia when education was managed according to legal documents, such as “Education Law”, “Education Edict”. Educational management units as well as managerial positions in educational sector were founded and appointed, including: Education Committee, Director of Education, Inspector of Education, and so on. In the meantime, educational policies were institutionalized, people in common and women in specific had more chances for the right of equality in education. Women’s positions and rights were then improved in comparison to the past and other countries in South East Asia at the current time, when most of women were denied the rights for education in a patriarchal society with the perspective that women’s main job should be house caring.

Second, an educational policy established, directly governed and managed by colonial government.

After finishing conquering Indonesia and Malaya, both Dutch and British people wanted to build up a system of education and administration to maintain their influence and create social order and stabilization. Therefore, an education system was established to train Indonesian staff, appoint them into different positions in the government and labor force (of low level), which was directly controlled by the colonial government. With the conquering policies of Dutch and British colonists, Indonesia and Malaya had a united authority for the whole country and a quite thoroughly developed education, which was better than in the previous stage. Impacts from educational policies brought about by western colonial government lifted Indonesia and Malaya to a new height, from a wild country in not only administration but also education.

Third, education deeply influenced by the “Divide and Conquer” policies of Dutch and British colonists.

Being influenced by the “Divide and Conquer” policy, Dutch and British colonial government constructed different school systems for each ethnic groups inhabited in colonial nations. British people built up 4 school systems, namely British schools, Malay schools, Chinese schools and Indian schools with respective teaching languages of English, Malay, Chinese and Tamil, which were designed for specific ethnic group speaking their mother tongue, preventing the people from joining schools of other groups. Meanwhile, Dutch people established three school patterns, namely Hollandsch Inlandsche School – HIS, Europeesche Lagere School – ELS, Hollandsch Chinese School – HCS, all of which followed westernized patterns and used Dutch as the main language; however, learners were not allowed to join schools of other communities. When giving comment on the educational programs of British people in Malaya, Chai Hon Chan confirmed: “social differences appeared between the English-educated Chinese and the Chinese-educated Chinese, as there did between the English-educated and vernacular-educated among the Malays and Indians” [Chan, 1977, p. 27].

The existence of different school patterns, on the one hand, was originated from the needs of different ethnic groups, as schools acted as the places for propagating cultural, religious values of each community; on the other hand, the most important thing was that the colonial government wanted to take advantage of that belief to maintain many local school patterns so as to make sure that although located closely, those ethnic groups could not be united into one force that might prevent the colo- nial benefits. Obviously, the existence of different school systems resulted in regional preference, partly facilitated the formation of communalism, a risky ideology preventing the unity among ethnic groups. The consequence of this policy was that people’s communities were isolated in their own cultural and social environment.

Fourth, dual education implemented by both the Netherland and Great Britain in the colonies.

Another similarity between Dutch and British educational policies for colonial Indonesia and Malaya was the dual education implemented throughout the conquering period. With this dual educational policy, there existed an “elite” education in western orientation especially for children from noble families, and another programs with rural features for the majority of people from lower class, mainly farmers and fishers. The aim of this dual education policy was to “on the one hand, gain agreement from the upper class, and on the other hand, cease the development of knowledge and economical ability of people from lower classes, preventing liberal and independent ideologies” [Hien, 2017].

Under the influence of the “dual education” of the colonial government, the new intellectuals of Indonesia and Malaya communities were divided into two wings with two different educational systems: one followed westernized orientation and the other belonged to local education. Taking that educational system would gift promotion chances in careers, because the colonial government only recruited those trained in westernized education patterns, being fluent in foreign languages and loyal to the colonial government. Ethnic discrimination could be seen in not only in education, but also in appointment and payment. “With the same qualifications, in the same major, even with more qualified academic results, the promotional routes of native people were always harder” [Khanh, 2012, p. 248]. Consequently, along with other policies in their colonial conquering, the “dual education” policy for the noble class and farmers, Indonesian and Malay social classes, as well as European people were always in the system of “Divide and Conquer”.

First, when comparing the two educational policies, it can be seen that the pattern employed by the Dutch in Indonesian communities was more lenient than that applied by British government in British Malaya. Although sharing the same target of serving the needs of the governing authorities in colony exploitation and culture synchronization, Dutch colonists permitted learners in Indonesia to have more chances to study and upgrade their knowledge. On the other hand, education for Malaya commoners followed the simplest form and limit higher education, while children from noble families were provided with programs in English, creating favourable conditions for them to approach new knowledge. Besides, Dutch education allowed learners from different classes to follow higher levels, even though they had to spent more time and took many examinations.

Second, although both Dutch and British colonists founded the dual education with the separation in the education systems for elite and common classes of people, with respective languages for teaching, Dutch people seemed to be more elastic with their flexibility in choosing languages, not as hard as British people in implementing policies on native people. The Dutch people considered their language as mandatory in westernized educational system, and Melary language was looked down on. However, in the educational programs for commoners, the Dutch still introduced their language into the curriculum, besides Melaru as the main tongue. What’s more, the Dutch also established a program for higher education, providing chances to approach westernized patterns. In opposition, British people limited the chances for Malaya to contact English, the language which was only used in noble class as a means to bring the royal family closer to the colonists, while lower classed had few opportunities to get learn this language. Therefore, in order to attend English language schools, native learners had to pass many challenges and complete a 2-year English-training course in specialized classes (Remove Class) [Chuong, Linh, Phuc, 2021, p. 255].

Third, there was a lack of reformation in British educational policies in Malaya. Despite some certain changes based on background and demands, British educational policies did not have any real reformation and thus, failed to break the traditional education down. While the Dutch brought about noticeable improvements through two educational reforms, which helped westernized educa- tion to be formed step by step throughout Indonesia, a controlled program aiming at “assimilating” native people.

The appearance of western colonialism, along with colonial governing policies in Indonesia and Malaya were considered as a factor that resulted in breaking down the traditional feudal social and economic structure which had long been in existence in these countries. Especially since the 2nd half of the 19th century, when western colonialism shifted into imperialism, both Dutch and British colonial governments wanted to become powerful countries in economy and expand their influence all over the world. Therefore, along with growing the colonial areas, colonist leaders fostered their colony exploitation in strong coordination with business profits to provide goods for exports and meet the demand of raw materials.

To comply with the international growing trends of capitalism’s manufactory process, SouthEast Asian countries, including Indonesia and Malaya, had to join the cycle of capitalism, which was a necessity of history. The force of Western capitalists acted as a catalyst to motivate the needs of accepting western civilization in economy, politics, culture and society. Among them, education was regarded as the core issue to change and provide conditions for national development in the following stages; especially in the current internationalization. From the educational policies of the colonial government in colonial periods, approaches to westernized educational patterns were open, shifting from religion-educating to learners’ thinking developing, approaching natural and social sciences, addressing vocational and physical training. In addition, sending native people oversea for education was also a developing trend that the whole world is aiming at. It could be admitted that, in order to integrate with modern education, education in Indonesia and Malaya in specific, and throughout South-East Asia in general, needed to be renovated, with more emphasis on vocational, physical and art training, along with an increase in foreign language education, especially English.

Indonesia and Malaya education in colonial periods had generalized features and high development. Under the impact of an improved education in westernized orientation, Indonesia and Malaya education had several important shifts, which went on to complete the secular educational system.

Regarding subjects following westernized education: Prior to the arrival of the Dutch and British people in Indonesia and Malaya, the education in these native lands were mostly based on religion, with subjects of history, literature and Islam bible, and other physical classes; but a lack of natural science – mathematics, arithmetic, etc., which lessened the effectiveness of secular education. Besides, religious classes were not clearly divided into levels as present, and thus, unsuitable for the need of development and education of learners in different age groups. In colonial era, Dutch and British government founded school that taught foreign languages, with Dutch language in Indonesia and English in Malaya introduced to curriculum, in combination with many secular subjects of natural and social science, physical and vocational training. All these helped thoroughly educate Indonesian and Malay people. In addition, the colonial government also sent learners oversea to study, providing conditions for them to acquire progressive ideologies of western countries. Well-trained and educated groups of people came into existence since the early time, such as teachers, journalists, civil servants.

Concerning educational system: With the educational policies of the Netherland and the Great Britain, a multi-level education was moulded in Indonesia and Malaysia with a full range of levels from primary, secondary to university as the highest. This was the result of various methods of the colonial government to develop the education for the majority of people, and also the foundation for Indonesia and Malaya divide educational levels as well as school ages for their modern education today.

About management pattern and methods: the construction of westernized education of the colonial government expressed the professionalism in management. The whole innovative educational system (either public or private) was under control of the authorities, from administration, course books, teaching staff to testing, evaluating and ranking academic performance, which created a uni- ty in performance as well as training, and thus, helped to run the system effectively, increasing the training quality in the new education.

Relating to school ages: Educational policies of the Netherland in Indonesia and the Great Britain in Malaya set an earlier school age than the traditional one (6 years of age, instead of 8). This rule, at first, was appropriate with the children’s physio-psychological state, as they had achieved a certain level of mental and physical development at this age, sufficient to meet the demand of learning. At present, 6-year-old is also the starting age for education applied in many countries worldwide. Secondly, two more early years in education provided children in Indonesia and Malaya with more chances for sooner contacting and acquiring modern knowledge, expanding the environment and communicating skills. Thank to that, their understanding and activeness could be soon formed, which is crucial and necessary in such a developing world like today.

The educational policies of the Dutch colonial government in Indonesia and the British in Malaya created a generalized education: from a wide country in administration and education, with those educational policies, Indonesia and Malaya were able to have a rather thoroughly developed education, much more progressive than other nations in the area. Some primary and secondary schools were even as developed as European schools. The basic aim of those policies was for colony conquering and exploitation, with school system from primary to university levels serving for training a staff work in colonial administration; however, they also had positive impact on the development of the nations, with a rapid increase in the number of schools and learners. Schools were founded everywhere, from city centers to remote rural areas.

In the implementation of the educational policies, colonial government favoured female education: when westernized patterns were applied in colonial areas, girls were allowed to go to school. From being limited in domestic science and household arts, the subjects were expanded to more general knowledge, which had big impact in increasing educational level (reading and writing ability) among women in specific and all people in general, helping to improve the rate of high education of these countries, providing favourable conditions for current international integration.

The colonial government focused on developing vocational education in Indonesia and Malaya: in the educational system founded by the colonial government, career-oriented subjects were formally introduced into curricula as compulsory ones from primary to secondary levels. What’s more, there were specialized universities and colleges established for specialized training, such as pedagogy-agriculture-medicine schools. The common feature in career-oriented training within dual educational policies conducted by the Dutch and British people in Indonesia and Malaya was that vocational training was favoured and each ethnic group had its own program. This policy helped to diversify the majors, increase active ability for learners, create the foundation for them to acquire modern knowledge from the West, meeting the new social demand as well as the reconstruction of the counties after gaining independence, and then, the international integration in current days.

A progressive social class was formed from the intellectuals who joined in people’s liberating movements: although the target of the Netherland and the Great Britain in implementing those educational policies was to train agents for their conquering and governing colonial people, “It’s this educational system that created a force of Westernized educated people, many of whom had the ideology of nationalism, opposing to the wish of the colonial government” [Thanh, 2014, p. 39]. “It was the force that raised the national flag, leading Indonesian people into the fights for people liberation through encouraging people’s culture, awakening people’s awareness, asking for the rights to have freedom-equality-educational and economic development, and then moving up to gain independence in their own ways” [Tan, Loc, 2014]. Similar situations could be witnessed in Malaya, when “the “elite” trained in English schools and supported by colonial government cooperated with the intellectuals originated from farmers and trained in local education. The latter – from the 1920s – was on the rise in number and gradually enlightened in political-ideology, becoming the opposing force not only to the colonial government, the traditional noble class, but also the intellectuals trained by British education [Khanh, 2012, p. 254].

In conclusion, from the analysis as above, the innovative education in Indonesia and Malaya showed positive features in forming innovative educational system with management patterns, teaching curricula, vocational training which were completely new to the native society with long-lasting traditional religious education. All these features are still applicable to the current educational systems of Malaysia and Indonesia, at different levels. However, that education still had many limitations when considering the subjects approached as well as the real results achieved. In other words, the limitations not only lied in the educational system founded by the colonial government but also originated from the objectives that system aimed at.

This study utilized postcolonial theory as an analytical framework to examine the educational policies of the Dutch authorities in Indonesia and the British in Malaya during the colonial period. From a postcolonial perspective, the educational policies of colonial powers were tools to reproduce their domination and exploitation of the colonies. However, this process was not simply an imposition by the ruling side but rather a complex interplay between colonial interests and unintended objective impacts.

On one hand, the educational policies in Indonesia and Malaya served the “divide and rule” strategy aimed at consolidating the empire and exploiting the colonies. The parallel education systems of Western and indigenous education reflected discrimination based on class and race. The division of the education system along linguistic and cultural differences deepened community divides, hindering the integration process in colonial society.

On the other hand, from a postcolonial viewpoint, colonial educational policies also brought about some positive unintended impacts. The introduction of the modern Western education system contributed to advancing the modernization process, promoting mass education, increasing literacy rates among the population, and opening up new educational opportunities for women. Notably, colonial education inadvertently nurtured an intellectual class that absorbed progressive thoughts, becoming the first nucleus for the national liberation movements against colonialism.

Thus, the educational legacy left from the colonial era carries an intertwined duality. It reflects the imperialist nature, racial and class discrimination; but it also inadvertently opened up the origins and foundations for the development of modern education systems in present-day Indonesia and Malaysia. These complex legacies continue to influence and create tensions within the multi-ethnic, multicultural societies of Southeast Asia. However, if viewed objectively and with goodwill, they are also valuable resources to be utilized and promoted in the era of global integration.

Список литературы A comparative perspective of educational policies of the Netherlands in Indonesia and Great Britain in Malaya during the 19th and 20th centuries

- Azim F. Post-colonial Theory. In: The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism. Cambridge, 2008, vol. 9: Twentieth-Century Historical, Philosophical and Psychological Perspectives, pp. 237- 248.

- Chan C. H. Education and Nation - Building in Plural Societies: The West Malaysian Experience. Canberra, The Australian National Uni. Press, 1977, 116 p.

- Christie C. J. Lịch sử Đông Nam Á hiện đại [Modern History of South-East Asia]. Hanoi, National Political Publ., 2000, 420 p. (in Viet.)

- Chuong D. V., Linh N. T. V., Phuc N. H. Politiques éducatives des Anglais pour les Malaisiens indigènes et celles des Français pour les Vietnamiens (de la fin du xixe au début du xxe siècle) - étude comparative. In: Conférence internationale l'education Franco-Vietnamienne fin du xixè - début du xxè siècle. Hue, 2021, pp. 243-258.

- Frankema E. Why Was the Dutch Legacy So Poor? Educational Development in the Netherlands Indies, 1871-1942. Masyarakat Indonesia, 2013, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 307-326.

- Hall D. G. E. Lịch sử Đông Nam Á [History of South-East Asia]. Hanoi, National Political Publ., 1997, 1292 p. (in Viet.)

- Han L. P. The Beginning and Development of English Boys and Girls’ Schools and School Libraries in the Straits Settlements, 1786-1941. Malaysian Journal of Library & Information Science, 2009, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 57-81.

- Hien H. P. H. “Chính sách giáo dục của Anh đối với người Malay” [Educational Policies of the Great Britain for Malay People]. Vietnam Social Science Journal, 2017, vol. 12, pp. 90-98. (in Viet.)

- Khanh T. Lịch sử Đông Nam Á [History of South-East Asia]. Hanoi, Social Science Publ., 2012, vol. 4, 558 p. (in Viet.)

- Ozay M. A Revisiting Cultural Transformation: Education System in Malaya During the Colonial Era. World Journal of Islamic History and Civilization, 2011, vol. 1, pp. 37-48.

- Penders C. L. M. Colonial Education Policy and Practice in Indonesia: 1900-1942. PhD Thesis. Canberra, Australian National Uni. Press, 1968, 444 p.

- Phuc N. H. “Cải cách giáo dục của Hà Lan ở thuộc địa Indonesia (1893-1901)” [The Netherland’s Educational Reformations in Colonial Indonessia (1893-1901)]. Journal of Science & Education - Hue University of Education, 2018, vol. 2, pp. 78-87. (in Viet.)

- Phuong T. P. Giáo dục Việt Nam dưới thời thuộc địa huyền thoại đỏ và huyền thoại đen [Vietnamese Education in Colonial Period Red and Black Legends]. Hanoi, Hanoi Publishing House, 2020, 164 p. (in Viet.)

- Stevenson R. Cultivators and Administrators: British Educational Policy Towards the Malays 1875-1906. Oxford, Oxford Uni. Press, 1975, 240 p.

- Suratminto L. Educational Policy in the Colonial Era. International Journal of History Education, 2013, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 77-84.

- Suwignyo A. The Breach in the Dike: Regime Change and the Standardization of Public Primary School Teacher Training in Indonesia (1893-1969). PhD Thesis. Leiden, Uni. of Leiden Press, 2012, 468 p.

- Tan N. V., Loc N. T. B. “Nhìn lại phong trào vận động cải cách ở Indonesia, Philippines và Myanmar trong những năm cuối thế kỷ XIX đầu thế kỷ XX” [A Look Back on Movements for Improvement in Indonesia, Philippines and Myanmar in the Last Years of 19th Century and Early 20th Century]. Journal of South East Asia Studies, 2014, vol. 6, pp. 49-54. (in Viet.)

- Thanh H. T. “Sự phát triển của tầng lớp trung lưu Inđônêxia dưới thời kỳ trật tự mới (1966-1998)” [The Development of Indonesian Middle Social Class in the New Order Period (1966-1998)]. Journal of South East Asia Studies, 2014, vol. 4, pp. 38-43. (in Viet.)

- Tong H. V. Lịch sử Indonesia (Từ thế kỷ XIV - XVI đến những năm 1980) [History of Indonesia (from 14th - 16th Centuries to 1980s)]. Ho Chi Minh, Open Education Institute, 1992, 196 p. (in Viet.)

- Van L. T. “Chính sách giáo dục của Anh đối với cộng đồng người Malaya bản địa (từ nửa cuối thế kỉ XIX đến đầu thế kỉ XX)” [The Educational Policies of the Great Britain for Native Malaya Community (from the 2nd Half of 19th Century to Early 20th Century]. Journal of South East Asia Studies, 2011, vol. 5, pp. 11-23. (in Viet.)