A runic inscription at Kalbak-Tash II, Central Altai, with reference to the location of the AZ tribe

Автор: Kubarev G.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.44, 2016 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145287

IDR: 145145287 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0102.2016.44.4.092-101

Текст обзорной статьи A runic inscription at Kalbak-Tash II, Central Altai, with reference to the location of the AZ tribe

Old Turkic stone statues from the western part of the Asian steppes are distinguished by marked originality as compared to similar eastern monuments, for example, this being expressed in the wide occurrence of such iconographic motifs as hair in the form of braids, lapelled coats, stemmed cups, weapons with ring pommels, etc. (Ermolenko, 2004: 43). The objects that exemplify the originality of Western Turkic sculpture are of particular interest for research. One such object is an unusual statue from the location of Borili in Ulytau Hills, southwestern Kazakh Uplands (Sary-Arka). The study of the statue involves the search for parallels in the art of the Western Turkic Khaganate and Sogd (which have been already analyzed in several studies on sculpture, murals, coroplastics, etc. (Sher, 1966: 67, 68; Albaum,

1975: 30–34; Ermolenko, 2004: 38–41; and others)), or cultural impacts from the centers of the ancient civilizations in East Asia. The problem of attributing and dating the sculpture described in this article, with the help of material parallels, is complicated by an almost complete absence of such parallels among the regional materials, which demanded that the artifacts be addressed from the adjacent territories. This study focuses on the material complex embodied in the reliefs on the surface of the sculpture, while the interpretation of the sculpture will be discussed in a subsequent article.

Description of the statue

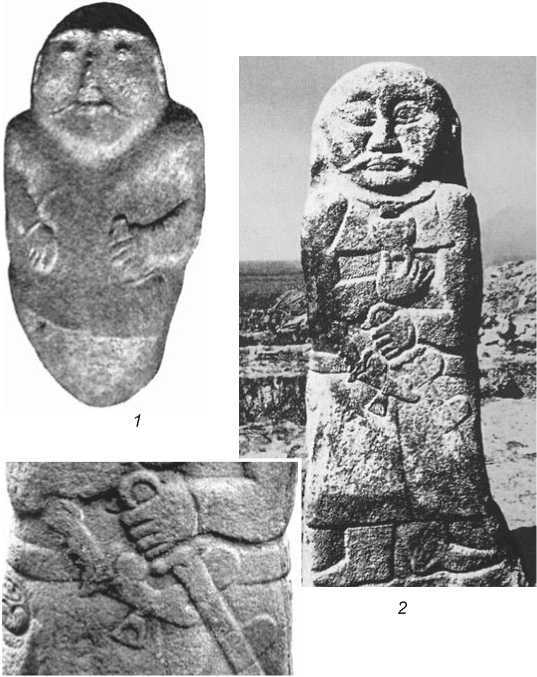

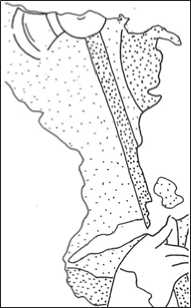

The statue was discovered in the location of Borili* at the confluence of the Tamdy and Terekty rivers (48º57′155′′N, 66º59′850′′E, at an altitude of 483 m). The statue was probably located at the site of its original setting, at the eastern tail of an earthen mound 12 m in diameter and 0.4–0.5 m in height. Stones, including white quartz, were found on the surface of the mound. A presumably later stone pavement 6 m in diameter and 0.3 m in height, with missing stones in the middle, was located on the western side of the earthen structure. The sculpture is made out of a block of pink, coarse granite and represents a man holding weapons in each hand (Fig. 1). The size of the sculpture is 195 × 25–44 × 10–22 cm. The convex shape of the block and the proportions of the sculpture are close to those of a real-life figure, and give the impression of a three-dimensional sculpture. The reverse side of the sculpture is covered with coarse spalling, and bears no representations.

Although the sculpture had been toppled and broken some time in the past, it shows a satisfactory degree of preservation, with most damage on the head, which was split off. The representations of ears, with rounded pendant earrings, can be discerned on the sides of the head, and the outlines of the nose and (wide?) mustache are distinguishable on the face. The body of the sculpture was broken into three parts; the right shoulder was damaged by the spall. A narrow segment-like bas-relief, divided by a longitudinal line, a representation of a two-row neck adornment (a torque?), runs around the base of the neck. Narrow bracelets are shown on the wrists. The

20 cm

Fig. 1. Stone statue from Borili.

lapels of the coat are indicated on the chest of the figure. Although the line showing the edge of the coat is absent, the placement of the right lapel over the left suggests the left overlap of the clothing.

The belt is indicated by such details as a rounded buckle with a segment-like hole for the belt, six round onlay plates (three in a row on each side of the buckle), and a small fragment of the belt on the right side. According to the design of the buckle, the belt was fastened on the side opposite to the overlap of the clothing: that is, on the right.

The hand of the half-bent left arm of the sculpture is above the belt, and is tightly holding the hilt of a long-bladed weapon (broadsword?) with an ovalring pommel and straight thin crossbar. A sheath with distinctive semicircular clips connecting the paired transverse braces is shown. The position of the sheath is almost vertical. A relief of a short-bladed weapon (knife or dagger) was carved below the upper clip and almost perpendicular to the broadsword. The blade of that weapon is enclosed in a sheath of asymmetrical triangular shape, with a similar device for fastening to

Fig. 2. Some parallels to the Borili statue in the Old Turkic figurative tradition.

1 – sculpture from the Chuy valley (Sher, 1966: Pl. XII, 51 ); 2 – statue from Aerkate (Aersyati, Bortala County) (Si chou zhi lu…, 2008: 238); 3 – fragment of relief on the sculpture from Aerkate. Ürümqi, Xinjiang Regional Museum.

the belt. The hilt of the weapon, located at an angle to the blade, is crowned with the ring pommel.

The right hand of the sculpture is below the belt, over the middle part of a battle axe whose blade is facing left towards the bladed weapon. The axe has a trapezoidal blade, a wedge-shaped striker, and a long, straight handle reaching the border of the lower untreated part of stone, which was dug into the ground. We may assume that the figure that was carved of granite might have leaned on this weapon like on a staff. An oval hanging bag can be seen at the belt on the right side of the figure. The upper flap* and a decorative edging, or the outline of a pocketcompartment sewn on the front side of the bag, are represented in relief. Two elongated objects “hanging” next to each other are carved under the bag. The front object (closest to the front plane) has the form of an elongated trapezoid with concave sides and a base, from which a triangle extends downwards possibly indicating a hanging truss. This object is probably also a small bag with a flap and a patch pocket. Its shape, locking system, and décor resemble a miniature quiver. We may assume that the bag was used for carrying elongated things (?). The rear object (closest to the back plane) apparently reproduces a whetstone with a hole for hanging.

Identification of representations with specific objects

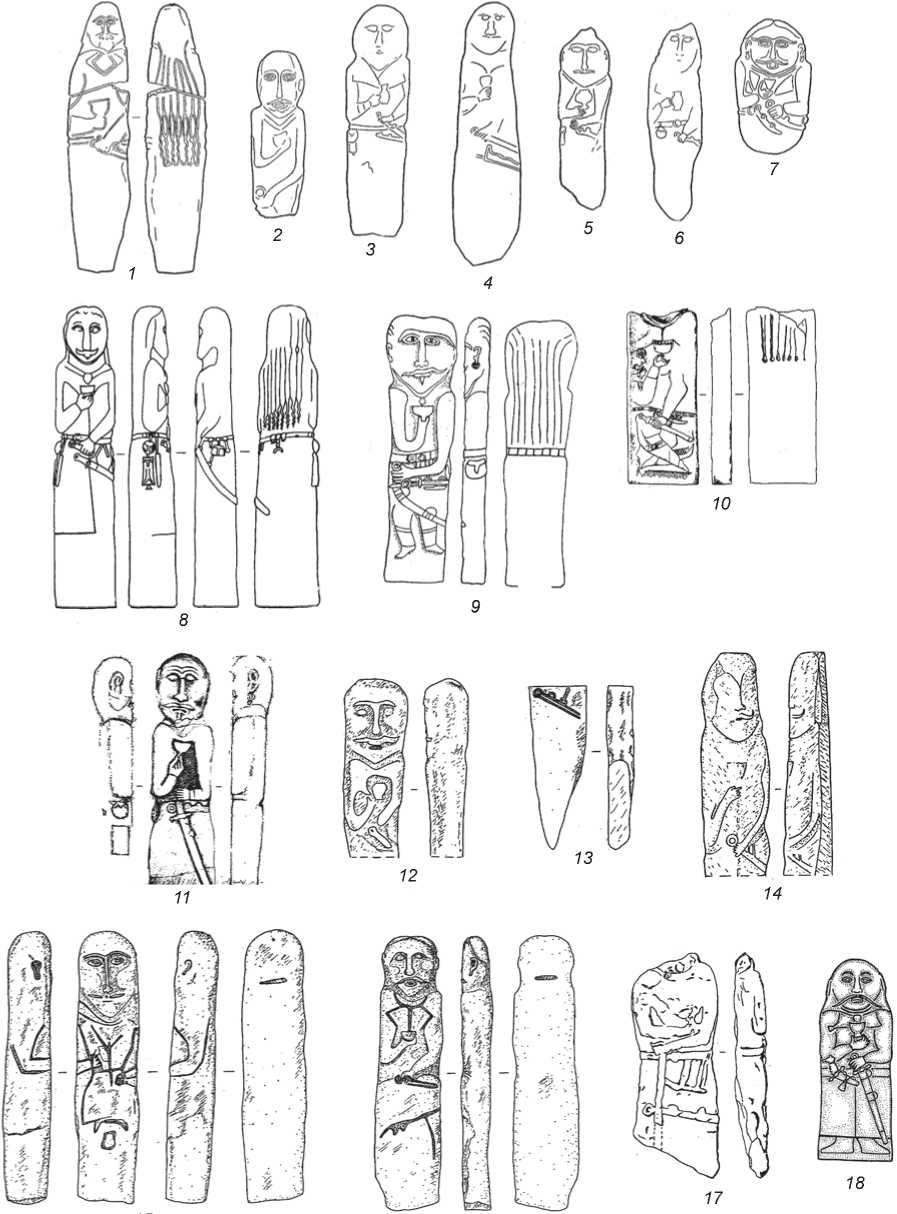

Atypical features of the statue from Borili include not only the position of its right hand, but also the attribute that the hand is “holding”. As a rule, in Old Turkic sculptures, the right hand is depicted bringing a vessel to the chest, and is placed above the left hand. According to the position of both hands, the object from the Chuy valley (Sher, 1966: Pl. XII, 51 ) is close to our statue. The photograph published by Sher shows no attribute in the right hand of that sculpture (or it is not discernible), while the sword, whose hilt is held by the left hand, is slanted in the same way (Fig. 2, 1 ). Furthermore, the description mentions a “kaptargak” (round bag) (Ibid.: 96).

Representations of bladed weaponry with ring pommels have been found only on Western

Turkic statues depicting men holding a vessel in the right hand. Besides the Semirechye, South, Central, and East Kazakhstan (Ibid.: Pl. II, 9–11 ; IV, 18 ; VI, 30 ; VII, 32 , 35 ; Arslanova, Charikov, 1974: Fig. 2, 8 ; Charikov, 1984: Fig. 1; 1989: Fig. 2, 1 ; Margulan, 2003: Ill. 24; Ermolenko, 2004: Fig. 5, 16 ; 9, 20 ; 33, 60 ; 61, 105 ; 62, 106 ; Baitanaev, 2004: 78) (Fig. 3, 1–10 ), the statue with such an attribute has been found only in East Turkestan. This is a massive sculpture 2.85 m high from Aerkate (Aersyati, Bortala County) (Hudiakov, 1998: Fig. 12; Si chou zhi lu…, 2008: 238) (see Fig. 2, 2 , 3 ; 3, 18 ). In addition to the pommel, long-bladed weapons that are depicted on the statues from Aerkate and Borili exhibit similar systems of attaching to the belt, semicircular sword belt clips on the sheath, and a position close to vertical. A long-lapelled coat, a torque (with a trapezoidal double pendant) on the neck, and earrings are also represented on the statue from Aerkate. The dagger on the belt of that sculpture also has an asymmetrical triangular blade; its outline can be discerned in the shape of the sheath decorated with a trapezoidal pendant-truss (?), and equipped with the same system of attachment to the belt as in the long-bladed cutting and stabbing weapons of both statues. The handle of the dagger, placed at an angle to the blade, has ribbed unilateral projections, which are well known

Fig. 3. Weaponry with the ring pommel hilt in the iconography of Old Turkic sculpture.

1–7 – after: (Sher, 1966: Pl. II, 9–11 ; IV, 18 ; VI, 30 ; VII, 32 , 35 ); 8 – after: (Arslanova, Charikov 1974: Fig. 2, 8 ); 9 – after: (Charikov, 1984: Fig. 1); 10 – after: (Charikov, 1989: Fig. 2, 1 ); 11 – after: (Margulan, 2003: Ill. 24); 12–16 – after: (Ermolenko, 2004: Fig. 5, 16 ;

9, 20 ; 33, 60 ; 61, 105 ; 62, 106 ); 17 – after: (Baitanaev, 2004: 78); 18 – after: (Hudiakov, 1998: Fig. 1, 2 ).

from illustrations of the attributes of Old Turkic statues (Evtyukhova, 1952: Fig. 67), and now also from the real finds in the Western Siberian forest-steppe region. Upon direct examination, the intricate pommel, whose shape in the published drawings resembles a small teapot (see Fig. 3, 18 ), turned out to be the same as in the sculpture from Borili; that is, in the form of a ring (see Fig. 2, 3 ). In terms of the mutual arrangement of both bladed weapons, the statue from Borili is similar to the sculpture found in the lower reaches of the Tamdy River (Ulytau) (Margulan, 2003: Ill. 24) (see Fig. 3, 11 ). The short-bladed weapon represented on this sculpture is located parallel to the belt and has a ring pommel. A rounded bag and a rectangular bag below are depicted on the right side. The decor of the upper part of the round bag, which is most likely a rendering of the flap, is similar to the same element on the Borili statue. A similar arrangement of weapons and a set of bags are represented on the statue from the Trans-Ili Alatau (the Semirechye) (Ibid.: Ill. 140, 141).

The position of long- and short-bladed weapons with ring pommels at an angle to each other is attested in the iconography of the sculpture from the village of Baltakol (South Kazakhstan) (Charikov, 1984: Fig. 1) (see Fig. 3, 9 ). Two paired clips with semicircular projections are shown on the sheath of a strongly-bent long-bladed weapon (a saber, according to A.A. Charikov), and two semicircular loops (most likely the same clips) with a bolster running around the external outline can be seen on the sheath of the short-bladed weapon. A rounded bag “with a profiled flap” is shown on the left side (Ibid.: 58). The intersecting long-bladed weapon with the ring pommel and a short-bladed weapon are represented on the statue from Karkaralinsk (Central Kazakhstan) (Sher, 1966: Pl. II, 11 ) (see Fig. 3, 3 ). The statue also bears the representations of the bags, connected and attached to the belt on the right: a round and a rectangular with a small protrusion on the bottom. The lapels of a long coat with the left overlap are also shown.

The combination of a round bag and a rectangular bag with concave sides and a protrusion (truss?) on the bottom appears on the statue from Kara-Koba, along with a rare detail for the Altai, the lapels (Kubarev, Kocheyev, 1988: Pl. 5, 7 ). A similar combination was found on several sculptures from Central Kazakhstan and the Semirechye (Margulan, 2003: Ill. 142; Ermolenko, 2004: Fig. 5, 15 ; Kurmankulov, Ermolenko, 2014: Ill. 119).

The statue from the Michurinsky state farm (East Kazakhstan) (Arslanova, Charikov, 1974: Fig. 2, 8; cf.: Sher, 1966: Pl. IX, 17) shows the greatest similarity to the Borili statue according to the combination of attributes. This is a realistic representation, close to the round sculpture, with braids and other details on the back surface (see Fig. 3, 8). The lapels of a long coat are visible on the chest of the statue (Ermolenko, 2003: Fig. 3); the edge of the coat continues into the outline of the upper right flap. Thus, the clothing has the left overlap, but the belt is buckled to the right. Oval-ring pommels are shown on both hilts of the bladed weapons. The shape of the cutting edge of the short-bladed weapon, closed by the hand, is unclear. The long-bladed weapon, whose representation continues to the side face, looks bent, and thus was identified by F.K. Arslanova and A.A. Charikov as a saber. As opposed to the statue from Borili, the bladed weapons on that sculpture are depicted parallel to each other and at an angle to the belt. The same direction of suspending the set of weapons with the ring pommel on the hilt was found on four more sculptures from South Kazakhstan and Semirechye (see Fig. 3, 4, 7, 10, 17) (Sher, 1966: Pl. IV, 18; VII, 35; Charikov, 1989: Fig. 2, 1; Baitanaev, 2004: 78). Two combined bags suspended from the belt are shown on the right side of the statue from the Michurinsky state farm. Their shape is the same as in the Borili statue, but the attribute identified with the whetstone is located in front of the bags. Similar combination of three objects with the representations of paired sets of bladed weapons (without pommels) and lapels has been found on two sculptures from Karatau (South Kazakhstan) (Margulan, 2003: Ill. 98; cf.: Sher, 1966: Pl. III, 16) and from Kypchyl (Altai) (Sorokin, 1968: Fig. 2, 1; cf.: Kubarev V.D., 1984: Pl. XXXIII, 198). Notably, the combination of bags (rounded and rectangular) and a whetstone, or of only such bags, has not been found on the Old Turkic statues from Tuva and Mongolia*.

Until now, axes have not been found among the sets of objects appearing in Old Turkic sculpture. Even though the representation of an axe tucked behind the belt (?) in an upturned position has been identified by V.D. Kubarev and V.A. Kocheyev (1988: Pl. 5, 6 , p. 213–214) on one of the Altai statues, the problem of the statue’s date remains unsettled. The axe suspended from the belt by the end of its long handle appears on several sculptures from the North Caucasus (Bidzhiev, 1993: 238–239, fig. 54, 57, 63). According to K.K. Bidzhiev (Ibid.: 244), these statues may be dated to the 12th–13th century transition or later. However, the axes mentioned above are different in their shapes from that carved on the Borili statue.

Pictorial parallels to the attributes of the statue from Borili occur among the sculptures and murals of the Sogdian towns. For instance, the reception of ambassadors by a Sogdian king (early second half of the 7th century (Marshak, 2009: 28)) is depicted on the western wall of room I in Afrasiab. The Turkic character wearing a long coat with lapels has a rectangular bag with a triangular

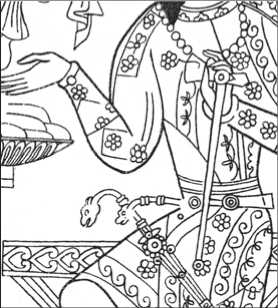

“appendage” at the bottom, suspended from the belt on the right, while a narrow object is represented nearby (in the front) (Albaum, 1975: Fig. 5, 6 ). Unfortunately, the section of painting from the waist to the low-hanging bag has not survived (Ibid.: Pl. VIII). Ring pommels on the sword hilts are shown in several representations of foreign ambassadors (Ibid.: Fig. 6, 11 , 14 ; 7, 24 , 25 ). According to the suggestion of L.I. Albaum, some of these characters might have arrived from China or East Turkestan (Ibid.: Fig. 6, 11 , p. 22), and others from Korea (Ibid.: Fig. 7, 24 , 25 , p. 75). The former have paired weapons, with the short-bladed weapon located almost horizontally and the long-bladed weapon at an angle; each weapon hangs from its own two semi-circular loops. The latter have only long-bladed weapons suspended at an angle on two figurate loops. Oval-ring pommel appears on the hilt of the dagger of one Turkic character (Arzhantseva, 1987: Fig. 4, 1 ).

The composition of the feast in the wall-paintings of room XVI/10 in Panjakent (Belenitsky 1973: Ill. 19) (late 7th–early 8th century (Marshak, 2009: 38)) shows parallels to the objects represented on the Borili statue. Some of the men, who are sitting in the oriental manner, are dressed in “Turkic” long coats with lapels; others are wearing robes with similar decorative details, but with the collar*. Bags are suspended on large rings from the belts on the right sides of the feasting men, and narrow objects can be seen behind the bags. Rectangular bags differ in the shapes of their bottom edges. Two characters have bags with the “appendage” on the bottom. Short-bladed weapons in sheaths are fastened horizontally to the belts of the participants in the feast with two loops; a ring pommel is distinguishable on the hilt of one of the weapons (Belenitsky, 1973: Ill. 21).

Three characters feasting under a canopy in the wallpainting of room VI/1 (Ibid.: 21) (early 8th century (Marshak, 2009: 43)) have bladed weapons, including paired ones, with ring pommels. Some scholars believe these nobles to be Turks (Lobacheva, 1979: 24) or Turgeshes (Ermolenko, Kurmankulov, 2012: 105). However, apart from the pommels, their intricately decorated weapons differ from the weapons represented in Old Turkic sculptures, as well as from other attributes, including clothing; although a small beard in the form of a vertical strip under the lower lip on the faces of the revelers is identical to the beard recorded on some Old Turkic statues (Ibid.: 97–103) (see Fig. 3, 9 , 11 ). The bladed weapon of a bearded man who is represented in the wall-painting of room XXI/3 conversing with a

*An Old Turkic statue representing the elements of a similar garment was found in the Altai. V.D. Kubarev (1984: 27) suggested that it depicted a Turkic long coat with buttoned lapels, and G.V. Kubarev (2000: 87) noted the influence of the Sogdian fashion.

noblewoman (Belenitsky, 1973: 32) is similar to the representations in the Old Turkic sculptures. Bladed weapons with ring pommels in the sheath with two clips and semicircular projections are fastened to the belt of the man. Although the man who is speaking to the lady is an important person and is dressed similarly to those who are feasting under a canopy, his weapons are not decorated*.

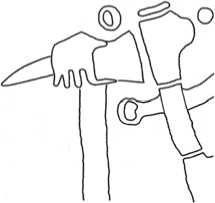

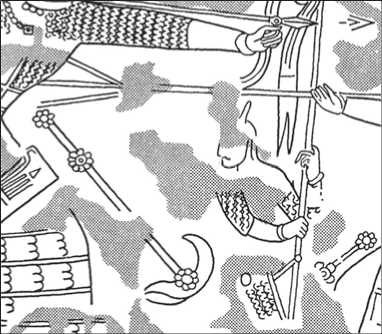

The various weapons depicted in the frescoes of the Sogdian towns include studded battleaxes. For instance, a young man is holding such an object on his shoulder in one of the compositions in the ceremonial hall VI/41 in Panjakent (Ibid.: 28) (blue hall with wallpaintings dated to ca 740 (Marshak, 2009: 40)). The axe is shown in side view; it consists of a pole-axe-like blade expanding towards the ends, a circular detail enclosing the socket, and a truncated-rhombic striker (Fig. 4, 5 ). A partial representation of a similar object was found in a fragment of wall-painting in the room I in Afrasiab (Albaum, 1975: Pl. L) (Fig. 4, 3 ). However, these axes, like an elegant two-sided axe—the royal insignia (Panjakent, room VI/1) (Belenitsky, 1973: 21) (Fig. 4, 2 ), and the cymbiform battleaxe of a jouster (Panjakent, room VI/1) (Ibid.: 19) (Fig. 4, 6 )—do not resemble the axe on the Borili statue.

We may find more parallels with the so-called dish from Kulagysh, which was made by a Sogdian metalworker in the 7th century (Marschak, 1986: Abb. 198). The scene of a combat between two military leaders wearing armor and tricorn headwear (helmets) is shown on the inner surface of the dish (Fig. 5, 4 ). Their weapons include long-bladed ones, whose sheaths are provided with paired clips with semicircular projecting petals, and axes with trapezoidal blades, wedge-shaped strikers, and sockets with rounded sides (Fig. 5, 5 ). However, the comparison of the axes remains relatively arbitrary, since the middle part of the axe on the statue from Borili is covered by the hand, and cannot be seen.

Riders that have studded battleaxes with eyelets that differ from those depicted on the dish from Kulagysh and, accordingly, on the statue from Borili, are shown on two almost identical Sogdian (Central Asian) dishes—the Verkhneye Nildino dish and the so-called Anikovskoye dish (Darkevich, Marshak, 1974: Fig. 3; Baulo, 2004: Fig. 1) (Fig. 5, 1–3 ). The former dish is dated to the 8th–early 9th century, while the latter dish is dated to different periods (Baulo, 2004: 132–133). It is important that (according to the conclusion by B.I. Marshak), the Anikovskoye dish was cast from an impression of the

Fig. 4. Axes in the medieval figurative tradition.

1 – Borili; 2 – Panjakent VI/1 (Belenitsky, 1973: 21); 3 – Afrasiab (Albaum, 1975: Pl. L); 4 – Shikshin (Dyakonova, 1984: Fig. 12);

5 – Panjakent VI/41 (Belenitsky, 1973: 28); 6 – Panjakent VI/1 (Ibid.: 19); 7 – village of Klimova in the Solikamsky Uyezd of the Perm Governorate (Smirnov, 1909: Fig. 306; fragment).

relief on the original 8th-century dish, and retained its details (Marshak, 1971: 11; Darkevich, Marshak, 1974: 217)*, including the axe. As a parallel to the rider with the axe, Marshak pointed to the representation of a 8th-century horseman in the paintings in the cave sanctuary in Shikshin (East Turkestan) (Marschak, 1986: Abb. 212, 10 ). However, in the drawing for the article by N.V. Dyakonova (1984: Fig. 12), the axes of two other “warriors of Shakya” (Shikshin sanctuary 11) are distinguished by the presence of the socket (see Fig. 4, 4 ).

A studded battleaxe with a trapezoidal blade and coracoid striker also appears in the Sasanian toreutics. On the dish with the image of the “Clock of Chosroes” (7th century (Trever, Lukonin, 1987: 111) or the late 7th–early 8th century (Marschak, 1986: Abb. 437)), this weapon is shown with its business end up on the couch of the king who is sitting in an oriental manner leaning on his vertically set sword (see Fig. 4, 7).

It should be noted that the characters armed with an axe, which appear in monumental painting and toreutics, usually carry the axe on their shoulders holding it by the handle. Only the ruler sitting on the throne (Belenitsky, 1973: 21) leans on the axe holding it by the round middle part, which can be seen since the palm of the hand is on the rear side of the axe (see Fig. 4, 2 ). The axe is near the chest of this royal person, while the end of the handle rests on his thigh. We should mention that axes, especially richly decorated ones, as well as maces, were high-status weapons in the retinues of Europe, North Asia, and China, and served as symbols of power (Raspopova, 1980: 76, 78).

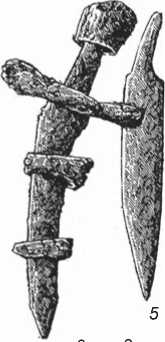

A certain material parallel to the weapons with ring pommels carved on Old Turkic statues is a luxury

Fig. 5. Representations of axes on Eastern metal dishware.

1 – dish from Malaya Ob (Verkhneye Nildino). Museum of History and Culture of the Peoples of Siberia and the Far East of SB RAS; 2 , 3 – fragments of reliefs, drawing by A.P. Borodovsky (Gemuev, Sagalaev, Soloviev, 1989: 54); 4 – dish discovered near the village of Kulagysh in the Kungursky Uyezd of the Perm Governorate; 5 – fragment of this dish with a representation of axes (Smirnov, 1909: Fig. 50).

broadsword from Pereshchepino (7th century); its hilt and sheath are decorated with embossed gold onlays (Sher, 1966: 42; Charikov, 1984: 59; 1989: 187). It was made by a Byzantine artisan in accordance with the “Avar custom”. Scholars find the typological equivalents of this obviously “custom-made” weapon, intended for a person of Khan level, among the finds from the burials of the Avar aristocracy of the 7th century in Hungary (Sher, 1966: 42; Sokrovishcha…, 1997: 89, 135). However, despite the similarities of the ring pommels on the hilts, the shapes of the petals on the clips of Avar sheaths for the swords, and on bladed weapons represented in stone, are different. The protrusions, which bear loops, on the clips of Avar weapons are of figurate shape consisting of three semicircles (Ibid.: 135).

According to Z.A. Lvova and B.I. Marshak, swords with ring pommels (along with pseudo-buckles) “were widespread in the steppes and the adjacent territories”

(Ibid.: 89). However, they have not yet been found in the western part of the Asian steppes, except for a broadsword from Berel, discovered by V.V. Radlov (Gavrilova, 1965: Fig. 4, 12 ; Soloviev, 1987: 67). But overall, an impressive number of bladed weapons of this kind (single-edged, with ring pommels and predominantly straight cutting-and-slashing edges) originated from the territories of the earliest states of East Asia. They were widespread in the military circles of Korea as early as the second quarter of the first millennium AD (Lee Sang-yeob, 2008: 92, 93). They are also well known in Japan. A representative series of such weapons, exhibiting both straight blades and blades with concave cutting edges, was found, for example, during the excavation of the Todaijiyama burial mound dated to the 3rd century AD (Yamato no…, 2002: 54). The rings of some pommels, which are round in cross-section, were decorated on the outside with flat-figured (including flame-like and leaf-shaped)

Fig. 6. Some parallels to the bladed weapon depicted on the Borili statue.

1–3 – hilts with the ring pommel; 4 – combat knife from the necropolis of Arkhiereiskaya Zaimka; 5 – bladed weapon from the Ryolka burial-ground.

3 cm

projections, altering the perception of the geometric simplicity of the object. In such cases, the outline of the ring might form a fairly intricate shape similar to that which the ancient artisan of the above-mentioned sculpture from Aerkate might have tried to render. For example, a small decorative “trefoil” was sometimes placed inside the ring (in a part adjacent to the hilt). An attempt to reproduce this element in such coarse material as granite, unsuitable for rendering small details, might have resulted in the appearance of a specific protrusion inside the ring of the bladed weapon on the statue from Borili. A beautiful inlaid ring pommel of an iron sword of the 6th century AD, with the hilt covered with bronze leaf, was found in the Okamine burial mound in the Nara Prefecture. Blades with ring pommels became one of the most common typological units of bladed weaponry in the Kofun period (250–538 AD) (Derevianko, 1987: 39). In China, long iron broadswords with ring pommels appeared in the period of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 AD) (Yang Hung, 1980: 124) and continued to exist until the time of the military operations of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army*.

Going back to archaeological materials, we should note a beautiful broadsword in a black lacquer sheath with gold inlay that once belonged to a high-ranking official of the early period of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (316–420 AD). This sword was found by Chinese archaeologists in burial 4 at Fuguishan not far from Nanjing**. The length of the broadsword is 96.9 cm; the width of the blade is 2.4 cm; the thickness of the back part of the blade is 0.6 cm. The broadsword had a ring pommel with a bronze rounded protrusion in its lower part (type 2) (Zhongguo…, 2015: 641), which appears to be identical to the one reproduced on the Borili statue.

Material parallels to the cutting and stabbing weaponry depicted on the statue from Borili may also be found among the objects from Western Siberia. Thus, the Elykaevo and Parabel collections contain bladed weapons with ring pommels, including pommels in the form of an open ring. One of the ends of the ring was bent close to the tang, but was not connected to it by forged welding (Soloviev, 1987: Fig. 12, 2 , 3 ; 14, 2 , 5–7 ; 15, 1 , 7 , 8 ). The final assembly of the hilt by placing wooden onlays with their subsequent attachment by threads, leather, or simply by winding around many layers of leather straps, would result in an “actual” ring pommel with a noticeable protrusion in its lower third (Fig. 6, 1–3 )*.

Parallels to the short-bladed knife or dagger with an inclined hilt, which is depicted on the Borili statue, can also be found among the materials originating from the necropolis of Arkhiereiskaya Zaimka in the Tomsk region of the Ob, dated (according to the material complex and a Tang coin) mainly to the 7th–8th centuries (Belikova,

*In recent years, there has been a tendency to date the Elykaevo hoard to the earlier period owing to clearly early materials in the hoard. However, the presence in the hoard of bladed weapons with a noticeable curvature of the blade, which in fact are early sabers, does not make it possible to agree with this approach, and gives grounds for dating the collection, still, to the Early Middle Ages (the 6th–8th centuries).

Pletneva, 1983: 37–41, 92, 95; Chindina, 1991: Fig. 21, 8 , 9 ; Soloviev, 1987: Fig. 26, 3 ), and among the objects from the Minusinsk Basin and the North Caucasus (Evtyukhova, 1952: Fig. 68). We should, however, make the reservation that in this case the similarity is relative— especially since we do not know anything about the design and shape of the bladed weapon hidden in the sheath that is represented on our statue. Regarding the Tomsk finds, we can only mention a similar angle of the hilt, the system of attaching to the belt, and, supposedly, the similarity of the working part. Moreover, the combat knife from the Ob region has a different pommel, in the form of a cap (Fig. 6, 4 ). Similar bladed weapons with slanting hilts have been found in this region at the Ryolka burial ground (Fig. 6, 5 ), where a slightly curved saber (broadsword, according to L.A. Chindina) with a clip-like pommel (in the form of a truncated ring) covered with bronze leaf has also been found (Chindina, 1977: 27, 28, fig. 6, 1 ; Soloviev, 1987: Fig. 17, 5 ; 26, 3 ).

Having analyzed the materials of Southern Siberia and Central Asia, Y.S. Hudiakov (1986: 157–158, fig. 71) noted the presence, albeit relatively rarely, of battleaxes in Old Turkic complexes, and included this type of weaponry into the typological and chronological matrix of the Old Turkic weaponry. Battleaxes equipped with an additional striker in the butt were customary for the population of the Minusinsk Basin throughout its entire Medieval history interrupted only by the Mongol invasion (Hudiakov, 1980: 62–65, pl. 16). However, the shape of the striking platform on the butts of these axes remained flattened, like hammer’s. Studded battleaxes with flattened upper platforms (Soloviev, 1987: Fig. 29, 1–3 ) were a part of the weaponry used by the inhabitants of the subtaiga and southern taiga regions of Western Siberia, who were strongly influenced by the Turkicspeaking population. However, a striker with a convex sector-shaped blade and a long sharp faceted pick-like butt, visually very similar to that depicted on the Borili sculpture, was found exactly here, in the Middle Ob region (Ibid.: Fig. 29, 4 ); although it should be noted that the Chernilshchikovsky burial ground, where that item was found, is heterogeneous in time*. Although the materials of the site include a large fragment of a broadsword with a figured bronze clip and braces from a system of attaching the weapon to the belt (Ibid.: Fig. 20, 11 ), similar to that described above, it is difficult to assign the axe definitively to the period that is of interest to us. As far as the Eastern European parallels are concerned, only a studded axe of the 6th century from the burial ground of Borisovo in the North

Caucasus (Kovalevskaya, 1981: Fig. 62, 58 ) bears some resemblance to the axe shown on the statue from Borili.

Conclusions

On the basis of the parallels listed in the article, the statue from Borili may be dated to the 7th–early 8th century, most likely the 7th century. Despite the specificity of the position of the right hand and the attribute determining this position, the rest of the statue does not differ from the “typical” Old Turkic statues. Moreover, it shows significant similarities with the Western Turkic statues that represent the elements of Turkic clothing and hairstyles. These parallels are found among the materials of Sogdian art; and, in part, in the Chinese pictorial tradition. Even previously, the comparison of the Old Turkic statues with the Sogdian and Chinese materials allowed scholars to identify the parallels in representations, gestures, and attributes. Thus, the iconography of some of the statues, including those depicting weapons with a ring pommel, contains elements similar to some motifs in Sogdian paintings (such as the refined gesture of the hand holding the cup, wavy stylized endings of braids-locks, etc.). It seems that in terms of its composition, the statue from Borili may be correlated in some way with the image of the ruler in the Panjakent monumental painting. The stability, wide prevalence, and importance of the combination of bladed weapons and axe among the “royal” attributes are manifested by the Iranian dish with the representation of the “Clock of Chosroes”.