A Survey on Deep Learning Techniques for Malaria Detection: Datasets Architectures and Future Perspectives

Автор: Desire Guel, Kiswendsida Kisito Kabore, Flavien Herve Somda

Журнал: International Journal of Information Technology and Computer Science @ijitcs

Статья в выпуске: 1 Vol. 18, 2026 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Malaria remains a significant global health challenge that affects more than 200 million people each year and disproportionately burdens regions with limited resources. Precise and timely diagnosis is critical for effective treatment and control. Traditional diagnostic approaches, including microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), encounter significant limitations such as reliance on skilled personnel, high costs and slow processing times. Advances in deep learning (DL) have demonstrated remarkable potential. They achieve diagnostic accuracies of up to 97% in automated malaria detection by employing convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and similar architectures to analyze blood smear images. This survey comprehensively reviews deep learning approaches for malaria detection and focuses on datasets, architectures and performance metrics. Publicly available datasets, such as the NIH and Delgado Dataset B are evaluated for size, diversity and limitations. Deep learning models which include ResNet, VGG, YOLO and lightweight architectures like MobileNet are analyzed for their strengths, scalability and suitability across various diagnostic scenarios. Key performance metrics such as sensitivity and computational efficiency are compared with models achieving sensitivity rates as high as 96%. Emerging smartphone-based diagnostic systems and multimodal data integration trends demonstrate significant potential to enhance accessibility in resource-limited settings. This survey examines key challenges and includes bias in the data set, generalization of the model and interpretability to identify research gaps and propose future directions to develop robust, scalable and clinically applicable deep learning solutions for malaria detection.

Malaria Detection, Deep Learning (DL), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Medical Imaging, Automated Diagnostics

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/15020187

IDR: 15020187 | DOI: 10.5815/ijitcs.2026.01.04

Текст научной статьи A Survey on Deep Learning Techniques for Malaria Detection: Datasets Architectures and Future Perspectives

Malaria continues to pose a significant global health challenge with over 247 million cases reported annually as of 2021 [1]. The disease predominantly impacts resource-constrained regions, including sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia and Latin America [1]. Among these populations, children under five years old and pregnant women remain the most vulnerable, experiencing elevated rates of morbidity and mortality. Despite considerable advancements in malaria control measures, the disease persists as a leading cause of illness and death, exacerbating socio-economic disparities in endemic areas.

Accurate and timely diagnosis is vital for effective malaria management, facilitating prompt treatment, reducing complications and lowering transmission rates [2, 3]. Traditional diagnostic methods, however, face significant challenges. Microscopy is resource-intensive and requires skilled personnel, while Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) offer faster results but demonstrate reduced sensitivity at low parasite densities [4, 5]. For instance, Delgado-Ortet et al. show that the performance of RDTs significantly declines in cases of low parasitemia, highlighting the limitations of these tests in early or asymptomatic infections [4]. Cunningham et al. further emphasize that while RDTs have improved access to malaria diagnostics, variability in test sensitivity and issues with heat stability in field conditions hinder their reliability [5]. Additionally, these methods are prone to human error, particularly in resource-constrained, high-burden settings [3, 6, 7]. These limitations underline the urgent need for automated, scalable and robust malaria detection systems to enhance diagnostic accuracy and accessibility.

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning, have revolutionized the landscape of automated malaria detection. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have shown exceptional promise, achieving diagnostic accuracies exceeding 95% by analyzing microscopic blood smear images (Rajaraman et al., 2019 [8]; Vijayalakshmi et al., 2020 [9]). These models not only reduce reliance on human expertise but also enable rapid, large-scale diagnoses (Chattopadhyay et al., 2019 [10]). Moreover, emerging techniques like transfer learning (Bakator et al., 2018 [11]; Vijayalakshmi et al., 2020 [9]; Yang et al., 2020 [12]; Nakasi et al., 2020 [13]; Khosla et al., 2020 [14]), hybrid approaches and lightweight models optimized for smartphone integration (Yang et al., 2019 [6]; Masud et al., 2020 [15]) have made it feasible to deploy deep learning-based systems in remote and underserved regions.

This paper aims to provide a comprehensive review of state-of-the-art deep learning approaches for malaria detection by focusing on datasets, architectures, performance metrics, edge-case challenges, interpretability and real-world applicability. The specific objectives of this study are as follows:

• To review and compare publicly available datasets commonly used in malaria detection research, including their characteristics, size, geographical diversity, disease variety (e.g., different Plasmodium species, mixed infections) and limitations.

• To analyze state-of-the-art deep learning architectures with an emphasis on CNNs, transfer learning, hybrid and ensemble models and their applications in various diagnostic contexts.

• To assess the extent to which deep learning models for malaria detection have been validated in real-world scenarios, particularly in remote or resource-constrained environments and to highlight gaps between laboratory performance and field deployment.

• To evaluate performance metrics and challenges faced by existing models, including accuracy, computational efficiency, generalizability across diverse datasets and robustness to edge cases such as rare malaria species, mixed infections, or poorly prepared slides.

• To examine strategies for enhancing model interpretability and explainability, highlighting approaches that can build clinical trust and facilitate integration of automated diagnostics in healthcare workflows.

• To identify current gaps in the literature and propose future research directions aimed at improving the robustness, scalability, interpretability and clinical adoption of deep learning solutions for malaria detection.

2. Overview of Malaria Detection Techniques2.1. Evolution of Malaria Detection Methods

The contributions of this paper lie in its holistic evaluation of existing techniques and its emphasis on practical applicability, particularly in resource-constrained settings. By addressing not only technical performance but also contextual aspects such as dataset diversity, edge-case handling, interpretability and field deployment challenges, this paper provides a roadmap for advancing reliable and clinically trustworthy automated malaria diagnostics across diverse geographical and healthcare environments.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 begins by providing an overview of both traditional and emerging malaria detection techniques, establishing the foundation for understanding the role of AI in this domain. Building upon this, Section 5 examines the publicly available datasets commonly used in malaria detection research, highlighting their characteristics and limitations. Section 6 then delves into the diverse deep learning architectures applied in malaria detection, evaluating their strengths and performance. To contextualize these findings, Section 7 presents a comparative analysis, shedding light on the trade-offs and practical applications of various approaches. Section 8 moves the discussion forward by addressing key challenges and outlining future research directions to advance the field. Finally, Section 9 concludes the paper by summarizing the key findings and their broader implications for malaria diagnostics and global health.

The detection and diagnosis of malaria have evolved significantly in recent decades, driven by the need for rapid, accurate and scalable diagnostic methods (Cunningham et al., 2018 [5]; Tangpukdee et al., 2009 [16]; Linder et al., 2014 [17]; Yang et al., 2019 [6]; Nakasi et al., 2021 [7]; Chibuta et al., 2020 [3]). Traditional approaches such as microscopy and RDTs have been widely used for malaria detection and remain integral in many clinical and field settings. However, these methods often face limitations in sensitivity, specificity and scalability, especially in resource-constrained environments. The emergence of advanced molecular techniques like Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) has introduced a higher level of precision but requires sophisticated infrastructure and expertise (Tangpukdee et al., 2009 [16]; Linder et al., 2014 [17]; Mfuh et al., 2019 [18]; Yang et al., 2019 [6]; Gidey et al., 2020 [19]). Recently, deep learning has revolutionized malaria diagnostics by enabling automated analysis of blood smear images with high accuracy and efficiency. This section provides a comprehensive overview of these techniques, from traditional methods to cutting-edge deep learning-based approaches, highlighting their principles, advantages, limitations and roles in improving malaria diagnostics across diverse settings.

Malaria remains a pressing global health challenge with millions of cases reported annually, disproportionately affecting sub-Saharan Africa and children under five years of age [1] with high mortality rates due to delayed or inaccurate diagnoses [16], compounded by problems such as the overuse of antimalarial drugs from presumptive treatments [5] and limited access to scalable diagnostic technologies in low-resource settings [3]. Early and accurate detection is essential to control the spread of the disease and ensure prompt treatment. Over the years, various malaria detection techniques have been developed, ranging from traditional laboratory methods to advanced deep learning (DL)-based approaches. This section provides an overview of the key techniques used in malaria detection, focusing on traditional diagnostic methods and the recent emergence of deep learning-based approaches.

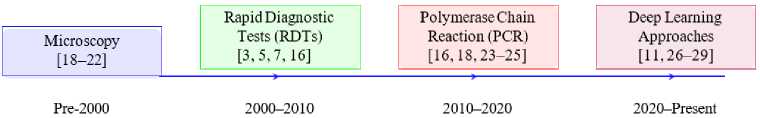

Fig.1. Timeline of malaria detection techniques

Fig. 1 shows the progressive evolution of malaria detection techniques by highlighting the transition from traditional methods to advanced deep learning-based approaches. Starting with microscopy [18–22], that remains the gold standard for malaria detection. This technique involves manual examination of blood smears to identify Plasmodium parasites. Despite its reliability, microscopy is labor intensive and highly dependent on the skill of trained personnel. To address the limitations of microscopy, RDTs [3, 5, 7, 16] emerged as a faster and more accessible diagnostic tool. RDTs rely on antigen-antibody interactions for detecting specific malaria proteins by making them suitable for field use, especially in resource-limited settings.

Continuing to advance, PCR methods [16, 18, 23–25] introduced molecular precision to malaria detection. PCR offers high sensitivity and specificity by amplifying Plasmodium DNA and enabling the detection of low parasite densities and mixed infections. However, PCR’s reliance on sophisticated laboratory infrastructure and technical expertise limits its applicability in remote areas [16, 18, 23–25]. The flowchart concludes with the emergence of deep learning approaches that have revolutionized malaria diagnostics. Using CNNs and other advanced architectures of deep learning models enable automated analysis of microscopic images by improving diagnostic accuracy and reducing the dependency on manual interpretation. These models are particularly valuable for the integration of diagnostics into mobile and digital health platforms, as they leverage advancements in artificial intelligence for real-time analysis [26], optimize resource utilization in diverse healthcare settings [27], enhance user-friendly interfaces for non-expert use [28], facilitate scalable deployment in telemedicine frameworks [29] and address key challenges of accessibility and cost-effectiveness in low-resource environments [11].

Table 1. Comparison of malaria detection methods

|

Methods |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

Accuracy |

Time |

Cost |

Portability |

Expertise Requirement |

|

Microscopy |

High |

Moderate |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

High |

|

RDTs [3, 5, 7, 16] |

Moderate |

High |

Moderate |

Low |

Moderate |

High |

Low |

|

PC R [16, 18, 23–25] |

Very High |

Very High |

Very High |

High |

High |

Low |

High |

|

Deep Learning (DL ) [6, 7, 30, 31] |

High |

High |

Very High |

Moderate |

Variable |

Moderate |

Low |

|

Hybrid Approaches [9, 15, 32] |

Very High |

High |

Very High |

Moderate |

High |

Moderate |

Moderate |

|

Mobile-Based Detectio n [3, 7, 12] |

Moderate |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

Very High |

Low |

The comparison of malaria detection methods, as outlined in Table 1, highlights the strengths and limitations of traditional and modern approaches. Microscopy, the standard for malaria diagnosis, offers high sensitivity but moderate specificity. It is a time-intensive process requiring skilled personnel and laboratory infrastructure. Despite its low cost, its reliance on expertise makes it less suitable for large-scale screenings in resource-limited settings.

RDTs provide a faster and simpler alternative with moderate sensitivity and high specificity. These tests are costeffective and well-suited for field applications but may lack the precision needed in certain clinical scenarios. PCR stands out with very high sensitivity and specificity, making it highly accurate for malaria diagnosis. However, its high cost and time-intensive nature, coupled with the need for advanced laboratory settings, limit its accessibility in low- resource environments.

Deep learning-based approaches offer a transformative alternative, combining high sensitivity and specificity with moderate processing time. Their cost is variable, as it depends on factors such as the computational resources required and the scale of deployment. Unlike traditional methods, deep learning models can be optimized for large-scale, automated analysis, offering significant potential for scalability and integration into health systems, especially in resource-constrained regions.

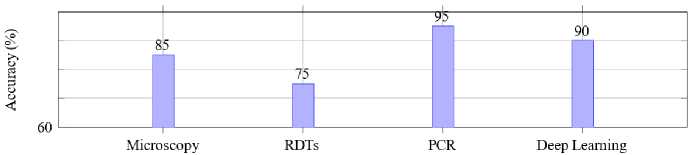

Fig. 2 compares the precision of various malaria detection methods: microscopy, RDT, PCR and deep learningbased approaches. Among these methods, PCR achieves the highest accuracy at 95%, showcasing its reliability for precise malaria detection. However, its application is often limited by high costs, the need for advanced laboratory infrastructure and specialized expertise.

Microscopy, a traditional diagnostic method, follows with an accuracy of 85%. While widely used, its accuracy heavily depends on the expertise of the technician and the quality of the blood smear preparation. RDTs, a more accessible and quicker diagnostic tool, exhibit a slightly lower accuracy of 75%, reflecting their potential limitations in detecting low parasitemia or mixed infections. Deep learning-based methods achieve an accuracy of 90%, demonstrating their strong potential for reliable malaria detection. These methods leverage large datasets and advanced architectures like CNNs and transfer learning models to provide a robust and scalable alternative for real-time and automated diagnostics, especially in resource-limited settings.

Fig.2. Accuracy of malaria detection methods

The comparison presented in Table 2 highlights the key aspects of traditional and deep learning-based malaria detection methods, showcasing their principles, performance and operational requirements. Traditional methods such as microscopy, RDTs and PCR remain widely used for malaria diagnosis due to their proven efficacy. Microscopy provides high sensitivity and specificity, heavily dependent on the skill of the microscopist and requires considerable time and expertise. RDTs, on the other hand, offer a faster alternative with moderate to high sensitivity and specificity, requiring minimal training for their use. PCR provides unparalleled accuracy with very high sensitivity and specificity but is limited by the need for specialized equipment, trained personnel and longer processing times.

Deep learning-based methods emerge as a transformative solution, automating the analysis of blood smear images with neural networks. These approaches demonstrate comparable sensitivity and specificity to traditional methods while significantly reducing the time to obtain results, often within seconds to minutes. Moreover, deep learning models require minimal operator expertise, provided the necessary computational infrastructure and pre-trained models are available. The efficiency and scalability of these methods position them as viable candidates for deployment in both resource-limited and high-throughput diagnostic settings, where rapid and accurate malaria detection is crucial.

-

2.2. Traditional Methods

Traditional methods of malaria detection have been pivotal in disease management and remain widely used, particularly in low-resource settings. These methods primarily include microscopy, RDTs and PCR, each with its distinct advantages and limitations.

Microscopy is considered the gold standard for malaria diagnosis, as it involves examining stained blood smears under a microscope to identify and quantify malaria parasites with high sensitivity (70-90%) and specificity (85-95%) [25], but its effectiveness is often hindered by operator skill variability, resource constraints and the need for sustained training to ensure diagnostic accuracy [33]. It is particularly valuable for differentiating between Plasmodium species and life-cycle stages. As Chibuta et al. (2020) [3] and Tangpukdee et al. (2009) [16] highlight, while microscopy remains the gold standard for malaria diagnosis is labor-intensive, time-consuming and heavily reliant on the expertise of trained personnel, leading to potential variability in results and susceptibility to human error. Despite these challenges, microscopy remains a cornerstone of malaria diagnostics in many parts of the world due to its costeffectiveness and diagnostic accuracy.

As Raju et al. (2024) [34] and Eshetu et al. (2024) [33] note, RDTs are immunochromatographic assays that detect specific malaria antigens in blood samples, delivering results within 15 to 20 minutes. With a sensitivity of 8590% and specificity of 90-95%, they are quick, user-friendly and well-suited for field conditions, particularly in remote or resource-limited settings. However, as explained by Raju et al. (2024) [34] and Eshetu et al. (2024) [33], RDTs are less effective at detecting low parasitemia and mixed infections and often lack the ability to differentiate Plasmodium species, limiting their diagnostic scope.

Table 2. Comparative analysis of malaria detection methods

|

Detection Methods |

Principle |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

Time to Result |

Equipment Required |

Expertise Needed |

|

Microscopy [18–22] |

Visual examination of stained blood smears |

High (depends on technician skill) |

High |

30–60 minutes |

Microscope |

Trained microscopist |

|

RDTs [3, 5, 7, 16] |

Detection of specific antigens via immunochromatography |

Moderate to High |

Moderate to High |

15–20 minutes |

Test kits |

Minimal training |

|

PCR [16, 18, 23–25] |

Amplification of parasite DNA |

Very High |

Very High |

Several hours |

PCR machine |

Specialized personnel |

|

Deep LearningBased [11, 26– 29] |

Automated analysis of blood smear images using neural networks |

High (varies with model) |

High |

Seconds to minutes |

Computer with appropriate software |

Minimal training |

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a molecular diagnostic technique that amplifies Plasmodium DNA, allowing for highly sensitive and specific malaria detection (sensitivity and specificity ¿95%) [25, 33]. PCR is especially effective for detecting low parasite densities and mixed infections, making it a reliable tool for confirmatory diagnosis and epidemiological studies. However, its high cost, technical complexity and need for advanced laboratory infrastructure constrain its use in resource-limited settings [35].

Table 3 summarizes the key characteristics of these traditional methods, providing a concise overview of their strengths and limitations.

Table 3. Comparison of traditional malaria detection methods

|

Methods |

Sensitivity/Specificity |

Advantages |

Limitations |

|

Microscopy [3, 16, 25, 33] |

Sensitivity: 70–90% • Specificity: 85–95% |

Low cost, species identification, parasite quantification |

Time-intensive, requires skilled personnel, prone to human error |

|

RDTs [9, 25, 33, 34] |

Sensitivity: 85–90% • Specificity: 90–95% |

Quick results, easy to use, suitable for field use |

Limited species differentiation, reduced accuracy at low parasitemia |

|

PCR [16, 25, 33, 35] |

Sensitivity: ≈95% • Specificity: ≈95% |

Highly accurate, detects low parasitemia and mixed infections |

Expensive, time-intensive, requires advanced infrastructure |

2.3. Emergence of Deep Learning

3. Related Surveys and Research3.1. Review of Previous Surveys on Malaria Detection and Deep Learning in Medical Imaging

In recent years, deep learning has emerged as a transformative approach in medical imaging, revolutionizing automated diagnostic capabilities. Specifically, in malaria detection, deep learning architectures, particularly CNNs, have demonstrated exceptional accuracy and efficiency in analyzing blood smear images. These models excel at learning complex features and patterns from images, enabling them to differentiate parasitized cells from healthy ones with minimal human intervention [10, 36]. Such advancements are especially beneficial in resource-limited regions where access to trained personnel is scarce, providing opportunities for standardized and rapid diagnosis.

Real-world implementations of deep learning models highlight their potential in combating malaria. For instance, Rajaraman et al. (2018) developed a deep learning model using transfer learning, achieving a diagnostic accuracy exceeding 95% when classifying parasitized versus non-parasitized cells [35]. Similarly, Vijayalakshmi et al. (2020) utilized CNNs integrated into mobile diagnostic platforms, demonstrating practical applications in field settings with limited infrastructure [9]. These successes underscore the viability of deep learning in delivering high-performance diagnostic solutions.

The benefits of employing deep learning for malaria detection are significant. Deep learning systems can rapidly analyze large volumes of blood smear images, yield consistent and accurate results while reducing human error. Furthermore, advancements in hardware optimization have enabled the integration of deep learning algorithms into portable devices, making real-time diagnostics feasible in remote or underserved areas [6, 37]. These systems not only enhance diagnostic efficiency but also facilitate broader epidemiological monitoring and resource allocation.

However, deploying deep learning models presents several challenges. One primary issue is the need for large, annotated datasets to train these models effectively. Collecting high-quality labeled data is labor-intensive, particularly in resource-constrained environments. Additionally, training deep learning models requires substantial computational resources, including GPUs or TPUs which may not be readily available in low-resource settings. Ensuring the robustness and generalizability of these models across diverse imaging conditions and equipment further complicates deployment [2, 38].

To address these limitations, researchers are exploring innovative strategies such as data augmentation, transfer learning and model optimization. Data augmentation techniques, including rotations, flips and synthetic image generation, help increase dataset diversity and mitigate overfitting. Transfer learning leverages pre-trained models to adapt to malaria datasets with limited samples, significantly reducing the computational burden as indicated by Dong et al. (2019) [35] and Rajaraman et al. (2018) [35]. Additionally, lightweight models like MobileNet have been proposed to balance computational efficiency with diagnostic performance, making them suitable for deployment on portable devices.

The rapid advancements in deep learning and its application to medical diagnostics have led to a growing body of literature focusing on automated malaria detection. This section provides a comprehensive overview of existing surveys and research, highlighting key contributions, limitations and the gaps addressed by this work.

The intersection of malaria detection and deep learning in medical imaging has been a significant focus of research in recent years. Existing surveys provide valuable insights into the advancements, challenges and applications of these technologies in clinical and remote settings.

-

A. Overview of Surveyed Approaches

Bakator and Radosav (2018) [11] conducted a comprehensive review of deep learning applications in medical diagnosis, emphasizing the dominance of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in processing medical images and their potential for malaria detection. Similarly, Gu et al. (2015) [39] explored advancements in CNN architectures, discussing their rapid evolution and their ability to extract complex patterns from medical images, which is critical for malaria diagnosis.

-

B. Focus on Malaria Detection

Tangpukdee et al. (2009) [16] highlighted the traditional methods of malaria diagnosis, such as microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), which, despite their widespread use, face limitations in accuracy and scalability. These limitations underscore the necessity for automated solutions powered by deep learning.

-

C. Integration of Deep Learning Techniques

Shetty et al. (2020) [40] examined the progression of deep learning techniques, including CNNs and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), in tackling unstructured medical data. Their survey emphasized the potential of these methods to revolutionize malaria detection by automating parasite identification and reducing diagnostic errors.

-

D. Challenges Addressed by Surveys

Cunningham and Gatton (2018) [5] r eviewed malaria diagnostic tools, focusing on product testing of rapid diagnostic tests and the role of computational methods in enhancing traditional approaches. Their findings highlighted gaps in scalability, robustness and field adaptability, which deep learning models are designed to address.

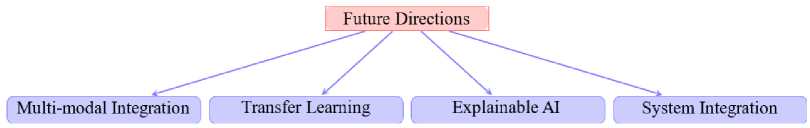

Despite their contributions, these surveys often lacked a holistic evaluation of the interplay between datasets, architectures and model performance, leaving gaps in understanding how these components influence the generalizability and robustness of deep learning models in malaria detection. For instance, the review b y [6] introduced the concept of mobile-based malaria detection using lightweight models, but this emerging trend was not adequately explored in other works. Moreover, the evolving role of multi-modal approaches, such as integrating genomic, clinical and imaging data, has been sparsely addressed in previous literature.

This paper seeks to fill these gaps by:

-

• Providing a comprehensive analysis of publicly available datasets, including their size, diversity and limitations.

-

• Critically examining state-of-the-art deep learning architectures, such as CNNs, transferring learning models and hybrid approaches with a focus on their performance in malaria detection.

-

• Highlighting emerging trends, such as lightweight models for mobile-based diagnostics, multi-modal

integration and the application of explainable AI (XAI) techniques for clinical adoption.

-

• Discussing the challenges of deploying deep learning models in resource-constrained settings, such as

-

3.2. Key Differences and Contributions of this Survey

computational requirements and model generalization.

This survey aims to bridge critical gaps identified in previous research by providing a comprehensive analysis that integrates datasets, state-of-the-art deep learning architectures and practical applications for malaria detection. The key contributions are outlined as follows:

-

• Datasets: A detailed evaluation of publicly available datasets, such as the NIH datase t [36], is presented. This includes an analysis of dataset diversity, quality and limitations, as well as their implications for model performance.

-

• Architectures: The survey provides an in-depth comparison of deep learning models, including YOLOv5 [41– 46], ResNet [43, 47–55] and VGG19 [13, 26, 56–59], assessing their strengths and limitations for malaria detection.

-

• Performance Metrics: Insights into model performance are provided, focusing on metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity and computational efficiency, especially in resource-constrained environments.

-

• Emerging Trends: The survey highlights novel applications, such as smartphone-based malaria diagnosis using lightweight models [12] and explores hybrid approaches combining traditional diagnostics with deep learning techniques.

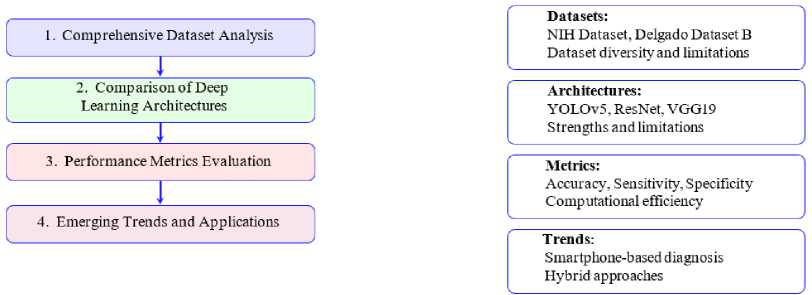

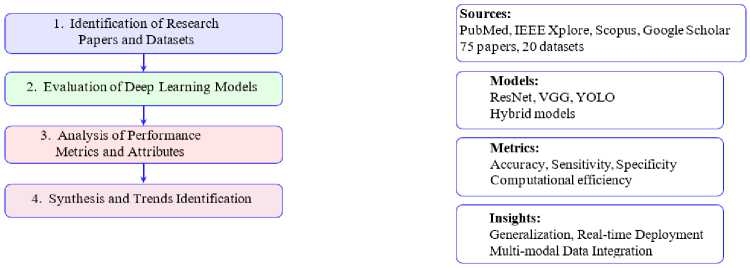

Fig. 3 shows the systematic approach of this survey, emphasizing its comprehensive coverage of datasets, architecture, performance metrics and real-world applications. The goal is to provide a holistic understanding of the role of deep learning in malaria detection while addressing the practical challenges of deploying these models in resource-limited settings.

Fig.3. Key features covered in the survey

Table 4 compares existing surveys on malaria detection, highlighting their focus areas and limitations. Previous works such as [2] and [38] have provided foundational insights into image processing and early deep learning techniques but often lacked comprehensive evaluations of modern architectures and dataset diversity.

Table 4. Comparison of related surveys on malaria detection and deep learning

|

Survey |

Focus Area |

Limitations |

|

Poostchi et al. (2018) [2] |

Image processing techniques for malaria detection |

Limited discussion on deep learning and dataset diversity |

|

Bakator et al. (2018) [11] |

Deep learning in medical imaging |

Focused primarily on general medical applications |

|

Mfuh et al. (2019) [18] |

Comparison of traditional diagnostic methods |

No integration with deep learning approaches |

|

Bibin et al. (2017) [38] |

Deep belief networks for malaria detection |

Limited exploration of newer architectures |

|

Yang et al. (2020) [12] |

Smartphone-based malaria detection |

Narrow focus on mobile applications |

|

Rajpurkar et al. (2017) [60] |

Adaptive survey methods using reinforcement learning |

Lacked integration with image-based detection techniques |

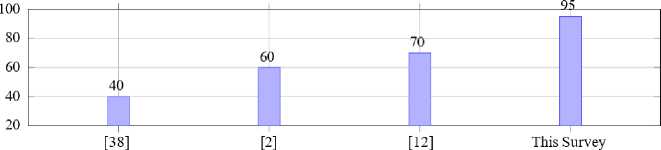

Fig. 4 evaluates the breadth of coverage of existing surveys compared to the current work. The results have been derived by evaluating the coverage of various surveys on malaria detection and deep learning in medical imaging, calculated as the percentage of addressed topics relevant to the domain, based on a predefined scoring rubric across the cited references ([38], [2], [12]) and the current survey. While previous studies have made valuable contributions, they often lacked depth in key areas such as hybrid methodologies, performance metric analysis and real-world applicability.

Fig.4. Comparison of survey coverage scores

4. Methodology

This section outlines the systematic approach adopted to review, evaluate and synthesize deep learning methodologies for malaria detection, encompassing dataset selection, model evaluation, performance analysis and the identification of key challenges and future trends.

-

4.1. Overview of the Survey Methodology

This survey adopts a structured and systematic methodology to review and analyze deep learning approaches for malaria detection. The process is designed to ensure the inclusion of high-quality studies and datasets, comprehensive evaluation of model performance and synthesis of insights into trends and challenges. The methodology comprises four key steps, detailed below and depicted in Fig. 5.

Step 1: Identification of Research Papers and Datasets

A comprehensive literature review was conducted, focusing on studies published between 2017 and 2024 in high-impact journals and reputable conferences. Search engines and databases such as PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus and Google Scholar were used to identify relevant papers. Inclusion criteria emphasized studies focusing on deep learning applications for malaria detection with a preference for those employing publicly available datasets. This ensures reproducibility and accessibility for further research. A total of 75 research papers and 20 datasets were included for detailed analysis.

Step 2: Evaluation of Deep Learning Models

Various deep learning architectures, including ResNet, VGG, YOLO and hybrid models, were assessed for their applicability to malaria detection [9, 11, 32, 39]. This evaluation involved analyzing the models’ performance on classification, detection and segmentation tasks using standard metrics like accuracy, sensitivity and specificity [3, 7, 61]. Comparative insights were drawn to identify the most effective architectures for specific diagnostic scenarios, highlighting the strengths and limitations of each model in terms of generalizability and computational efficienc y [12, 31, 45].

Step 3: Analysis of Performance Metrics and Attributes

Critical performance metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity, precision and computational efficiency were examined to evaluate the robustness and generalization of the models [3, 7, 11]. Special attention was given to computational resource requirements and the scalability of models in resource-constrained settings [12, 31, 61]. The findings from this step facilitated a nuanced understanding of the trade-offs between accuracy and efficiency in deploying these models, especially for real-world applications in low-resource environments [7, 9, 45].

Step 4: Synthesis and Trends Identification

The final step involved synthesizing findings from the previous stages to identify emerging trends and challenges in the field [7, 9, 11]. Key areas for improvement, such as model generalization across diverse datasets [12, 31], integration of multi-modal data [3, 7] and real-time deployment capabilities [32, 45, 61], were highlighted. This synthesis provides actionable insights to guide future research efforts, emphasizing the need for robust and scalable solutions in malaria detection [9, 11].

Fig.5. Survey workflow for methodology

Table 5. Criteria for selecting research papers and datasets

|

Criterion |

Description |

|

Publication Date |

Studies published between 2017 and 2024 |

|

Journal/Conference Quality |

High-impact journals and reputable conferences |

|

Focus Area |

Deep learning techniques for malaria detection |

|

Dataset Accessibility |

Publicly available datasets |

|

Performance Metrics |

Use of standard metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity and precision |

-

4.2. Criteria for Selecting Research Papers and Datasets

The selection criteria for research papers and datasets were designed to ensure relevance and quality. The following factors were considered:

-

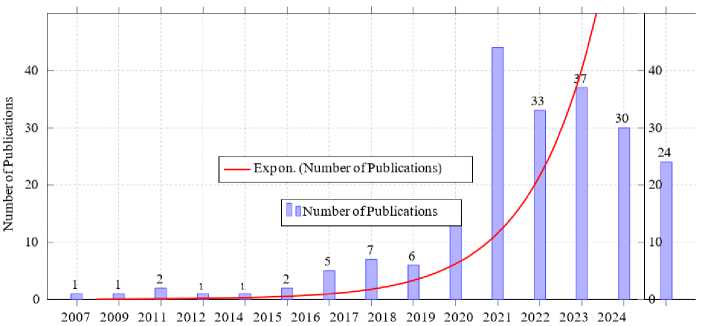

• Publication Date: Studies published between 2007 and 2024 were included to ensure the relevance of findings. Fig. 8 shows the trends in the number of publications related to malaria research over time, spanning from 2007 to 2024. It is evident that malaria research has seen a steady increase in publications over the years. The early years (2007-2015) exhibited minimal growth with fewer than five publications annually. Starting in 2016, the number of publications began to rise significantly, reaching 14 in 2019. The rapid increase is more pronounced in 2020 which recorded the highest number of publications (44), signaling a peak in research activities possibly driven by advancements in machine learning and its application to malaria detection.

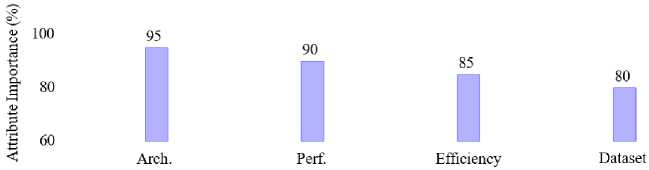

Fig.6. Importance of attributes in deep learning models for malaria detection

The exponential growth curve highlights a consistent acceleration in research output, emphasizing the growing interest and investment in leveraging technology for malaria detection and control. Although the number of publications slightly declined after 2020, the overall trend remains upward, showcasing the sustained momentum in this critical area of study.

-

• Journal/Conference Quality: Papers published in high-impact journals and reputable conferences were prioritized.

-

• Focus Area: Research focusing on deep learning techniques applied to malaria detection, including CNNs [62– 66], YOLO [41–46] and transfer learning models [38, 67].

-

• Journal/Conference Quality: As highlighted by Poostchi et al. (2018) and Rajaraman et al. (2019), papers published in high-impact journals and reputable conferences were prioritized [2, 8].

-

• Focus Area: As noted in studies by Turuk et al. (2022), Alnussairi et al. (2022), Loh et al. (2021a) and Umer et al. (2020), research focusing on deep learning techniques applied to malaria detection, particularly using convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has been extensively explored [62–66]. Additionally, as demonstrated by Sukumarran et al. (2024a), Terven et al. (2023), Zedda et al. (2022) and Jiang et al. (2021a), the YOLO algorithm has shown significant promise in object detection tasks for malaria diagnostic s [41–46]. Furthermore, transfer learning models, as discussed by Bibin et al. (2017) and Yang et al. (2019), provide an effective approach for leveraging pre-trained networks to enhance performance on malaria detection datasets [38, 67].

-

• Dataset Accessibility: As Dong et al. (2019) [36] and Nakasi et al. (2020) [13] highlight, publicly available datasets, such as the NIH, Delgado Dataset B and Dijkstra Dataset, have been instrumental in advancing research on malaria detection by providing standardized benchmarks for evaluating deep learning models.

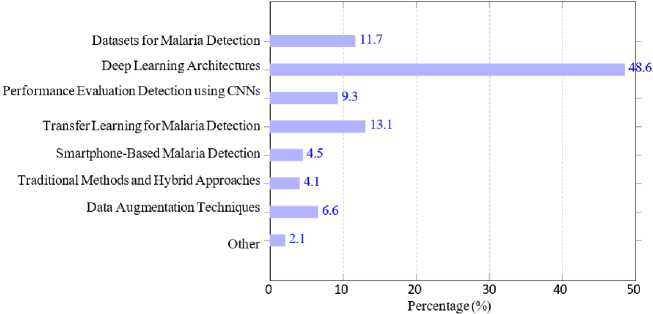

Fig.7. Distribution of publications in malaria research per category

Fig. 7 provides an overview of the distribution of publications across various categories related to malaria detection and deep learning. We categorize the research used in this survey into areas such as deep learning architectures, datasets for malaria detection, performance evaluation and specific methodologies like transfer learning and smartphone-based malaria detection. It is evident that Deep Learning Architectures [8, 9, 12–14, 27, 34, 35, 38, 49, 50, 53, 54, 62, 68–89] dominates the field, reflecting the primary focus on the development and application of these models for malaria detection. This is followed by Detection using CNNs [8, 12, 34, 50, 53, 54, 62, 80–88] and Datasets for Malaria Detection [9, 12, 13, 27, 30, 49, 50, 53, 69, 71, 74–80, 90–99] highlighting the importance of dataset availability and convolutional neural networks as critical components in advancing this research domain. Other notable categories include Performance Evaluation [13, 33, 47, 49, 50, 57, 69, 71, 99–109] and Traditional Methods and Hybrid Approaches [24, 33, 34, 51, 83, 93, 110–115].

Interestingly, categories like Data Augmentation Techniques [9, 14, 68, 69, 92, 108] and Smartphone-Based Malaria

Detection [12, 15, 48, 82, 98, 100, 109, 116, 117] have received comparatively less attention, despite their potential to address challenges like dataset diversity and accessibility in resource-limited settings.

This suggests future opportunities for exploring under-researched areas to enhance the robustness and applicability of deep learning models for malaria detection.

Fig.8. Trends in publications over time in malaria research

-

4.3. Description of Key Attributes Considered in Deep Learning Models

The analysis focuses on the following attributes of deep learning models for malaria detection, categorized for a comprehensive evaluation.

• Datasets for Malaria Detection: Examination of publicly available datasets such as the NIH dataset [8], Delgado Dataset B and others [9, 70]. Key factors include dataset size, class balance and annotation quality [2,15].

• Deep Learning Architectures: Comparative analysis of architectures like ResNet [43, 47–55], VGG [13, 26, 56–59], YOLO [38, 71] and custom hybrid models [9, 118].

• Performance Evaluation: Metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity, precision and F1-score are analyzed across different models [2, 12].

• Detection Using CNNs: Utilization of CNN-based models such as AlexNet, DenseNet and custom CNNs for malaria detection. This includes single-cell image classification and whole-slide analysis [8, 10].

• Transfer Learning for Malaria Detection: Use of pre-trained models like InceptionV3, Xception and MobileNet for transfer learning. Techniques include fine-tuning and feature extraction to improve performance on malaria datasets with limited labeled data [15, 37].

• Smartphone-Based Malaria Detection: Analysis of systems integrating deep learning models into smartphone applications for real-time diagnostics in resource-limited settings [13, 67]. Emphasis is placed on lightweight models and computational efficiency [15].

• Traditional Methods and Hybrid Approaches: Integration of traditional microscopy-based diagnostic methods with deep learning models to enhance accuracy and reliability [2]. Hybrid techniques combining rule-based systems with deep learning are also discussed [9].

• Data Augmentation Techniques: Importance of data preprocessing and augmentation strategies such as rotation, flipping and synthetic data generation to address class imbalance and enhance model robustness [2,14].

5. Datasets For Malaria Detection5.1. Publicly Available Datasets

The development and evaluation of deep learning models for malaria detection rely heavily on the availability of curated datasets that capture the complexity of blood smear images under varying clinical and environmental conditions. Over the past decade, several publicly available datasets have been released, each offering unique characteristics in terms of size, imaging modality, class balance and geographical diversity. These datasets serve as benchmarks for algorithm development and comparative studies, while also highlighting the challenges of dataset bias, class imbalance and generalization across diverse populations.

Several datasets have been curated for malaria detection, each with unique characteristics catering to various research needs. The most commonly used datasets include:

-

• NIH Dataset [8]: This dataset contains 27,558 labeled cell images classified into parasitized and uninfected categories. The NIH dataset is extensively used for training and evaluating malaria detection models due to its large size and balanced class distribution. Its thin smear images are well-annotated, making it suitable for deep learning approaches focused on binary classification tasks.

-

• Delgado Dataset B [46]: A smaller yet high-resolution dataset comprising 331 Giemsa-stained thin blood smear images. The high clarity of the images enables detailed morphological analysis of malaria parasites, making it ideal for fine-tuning advanced models like ResNet and YOLO architectures.

-

• Dijkstra Dataset [46, 71]: Featuring 883 high-quality images of both thick and thin smears, this dataset focuses on detecting Plasmodium falciparum . Its diversity in smear types helps evaluate models in environments where multiple smear types are encountered.

-

• Malaria-LMIC Dataset [15, 37, 67]: Designed to simulate real-world conditions, this dataset comprises approximately 5,000 images captured in low-resource settings. It emphasizes challenges such as poor image quality, diverse environmental conditions and class imbalance, providing opportunities to evaluate model robustness and adaptability.

-

5.2. Characteristics of Datasets

Table 6. Overview of publicly available datasets for malaria detection with key features

|

Dataset |

Image Type |

Size |

Key Features |

|

NIH Dataset [12] |

Cell images |

27,558 |

Parasitized/Uninfected, Thin Smears |

|

Delgado Dataset B [119] |

Thin smears |

331 |

High-resolution, Giemsa-stained |

|

Dijkstra Dataset [120] |

Thick and thin smears |

883 |

Focus on Plasmodium falciparum |

|

Malaria-LMIC [7] |

Real-world images |

5,000 |

Diverse, low-quality challenges |

|

IEEE Dataset [13] |

Thick smears |

2,000 |

Focus on P. falciparum and WBC localization |

|

Linder Dataset [17] |

Giemsa-stained blood smears |

50,000 cells |

Automated annotation for parasite localization |

|

Peruvian Dataset [121] |

Thick smears |

2,500 |

Wavelet-based features for species identification |

|

Malaria-TensorFlow [12] |

Smartphone images |

1,819 |

Open-source, mobile-aware imaging challenges |

The quality and diversity of datasets significantly impact the performance of deep learning models. Key characteristics include:

-

• Image Quality: High-resolution images are critical for accurate parasite detection and classification [2].

-

• Dataset Size: Larger datasets, such as NIH, provide better generalization capabilities for deep learning models. Smaller datasets often require data augmentation to overcome limitations [8].

-

• Diversity: The inclusion of diverse samples (e.g., different staining methods, malaria species) ensures

robustness [37].

-

• Class Balance: Many datasets suffer from class imbalance with fewer images of rare Plasmodium

species, potentially leading to model bias [12].

Table 6 shows the primary features of these datasets. While larger datasets like the NIH dataset support robust model generalization, smaller datasets with high-resolution images, such as Delgado Dataset B, are instrumental for precision tasks. The inclusion of diverse smear types in the Dijkstra Dataset enhances the flexibility of trained models, whereas the Malaria-LMIC dataset addresses real-world challenges.

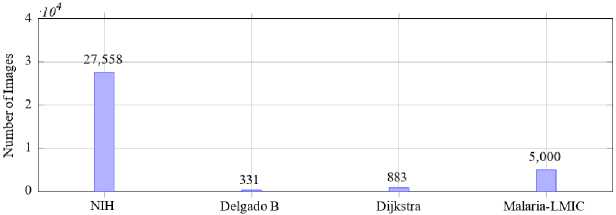

In Fig. 9, we compare four widely referenced datasets: NIH [48, 109, 116], Delgado B, Dijkstra and Malaria-LMIC [117]. The NIH dataset stands out with 27,558 images, offering a significantly larger volume compared to others such as Delgado B with 331 images and Dijkstra with 883 images. Malaria-LMIC provides a moderately sized dataset with 5,000 images. The disparity in dataset sizes underscores the variability in data availability with larger datasets like

NIH offering robust opportunities for deep learning model training and smaller datasets highlighting the need for data augmentation and transfer learning techniques to compensate for limited data.

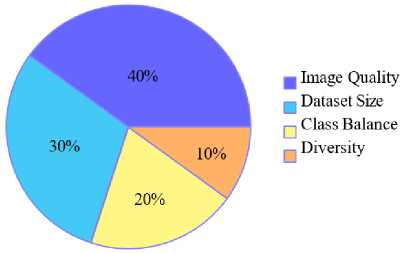

The results in Fig. 10 were obtained by aggregating expert evaluations and literature analysis to quantify the relative importance of dataset characteristics such as image quality, dataset size, class balance and diversity in malaria detection studies. Fig. 10 delves into the attributes essential for dataset quality and effectiveness.

As depicted in the pie chart, image quality accounts for 40% of importance, emphasizing the necessity of high-resolution, clear images for precise parasite detection. Dataset size contributes 30%, reflecting the critical role of ample data volume in ensuring model generalization and performance. Class balance and diversity contribute 20% and 10%, respectively, signifying their importance in mitigating biases and ensuring models are robust across various scenarios and populations.

Fig.9. Comparison of dataset sizes

Fig.10. Importance of dataset characteristics

-

5.3. Dataset Challenges and Limitations

Despite their usefulness, existing datasets present several challenges:

-

• Dataset Bias: As highlighted by Bibin et al. (2017) [38], datasets often reflect specific geographical or laboratory conditions, limiting their applicability to global contexts [7, 31].

-

• Need for Labeled Data: Poostchi et al. (2018) [2] and Yang et al. (2020) [12] emphasize, high-quality labeling requires significant expertise, particularly for annotating Plasmodium species and life-cycle stages.

-

• Dataset Quality: Nakasi et al. (2020) [13] and Vijayalakshmi et al. (2020) [9]. point out that variability in image quality, such as poor focus or staining artifacts, significantly impacts model performance.

-

5.4. Impact of Dataset Bias on Model Generalization Across Geographical Settings

-

5.5. Strategies for Addressing Class Imbalance in Malaria Datasets

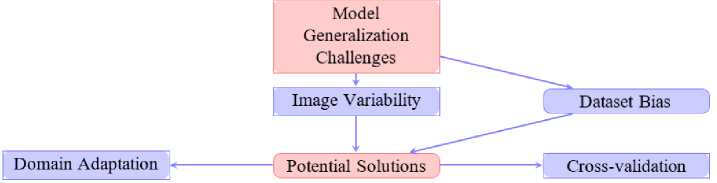

One of the critical challenges in developing deep learning models for malaria detection is the presence of dataset bias . Many publicly available datasets, such as those derived from laboratory-controlled environments or limited geographical regions, often fail to capture the full spectrum of variations encountered in real-world scenarios. This lack of diversity restricts the ability of models to generalize effectively when deployed in different clinical and environmental settings.

A major source of dataset bias arises from class imbalance. For instance, datasets frequently contain disproportionately more images of uninfected cells compared to parasitized cells, or an underrepresentation of rare Plasmodium species. Such imbalances lead to skewed learning, where models overfit to majority classes and underperform on minority classes, thereby reducing diagnostic reliability [12, 35].

Beyond class balance, geographical and laboratory biases also pose significant threats to model robustness. Studies such as Bibin et al. (2017) [38] have shown that datasets often reflect staining protocols, imaging equipment, or patient demographics specific to a particular region or research laboratory. Consequently, a model trained on one dataset may exhibit reduced performance when applied to samples from another geographical location with different preparation methods or patient populations [7, 31, 67].

This phenomenon highlights the gap between controlled experimental conditions and heterogeneous real-world deployments.

Dataset bias directly impacts model generalization. Limited diversity in training data hampers the ability of models to adapt to novel input distributions, resulting in poor cross-regional transferability. For example, a model optimized on a dataset collected in Southeast Asia may not perform reliably on samples from Sub-Saharan Africa due to differences in parasite prevalence, blood smear quality and imaging devices [2]. Such shortcomings undermine the clinical applicability of these models in resource-limited yet highly diverse environments.

To address these challenges, several strategies have been proposed. Data augmentation and synthetic data generation help alleviate class imbalance by artificially expanding minority classes [35]. Domain adaptation techniques allow models to adjust to differences in data distributions, improving their resilience across diverse populations and imaging setups. Additionally, cross-validation on multi-site datasets ensures that models are exposed to a wide range of conditions during training, thereby enhancing their robustness [35]. These approaches collectively contribute toward reducing dataset bias and improving generalization, paving the way for reliable deployment in global malaria detection initiatives.

Class imbalance is a recurring issue in malaria detection datasets, where certain Plasmodium species or infected cell categories are underrepresented compared to non-infected cells. This imbalance can lead to biased models that overfit to majority classes and underperform on rare but clinically important cases [8, 12]. To ensure robust and fair performance, several strategies have been developed to mitigate this problem:

-

• Data Augmentation: Traditional image augmentation techniques such as rotation, flipping, scaling and color jittering can artificially increase the diversity of minority class samples, reduce imbalance and improve generalization [35].

-

• Synthetic Data Generation: Advanced methods like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and synthetic minority oversampling techniques (SMOTE) have been applied to generate realistic parasite images, thereby enriching underrepresented classes [122].

-

• Over-sampling and Under-sampling: Over-sampling duplicates or generates additional minority class samples, while under-sampling reduces the number of majority class samples. These approaches help balance the dataset but must be carefully applied to avoid overfitting or information loss [123].

-

• Class Weighting in Loss Functions: Assigning higher weights to minority class errors during training (e.g., weighted cross-entropy or focal loss) ensures that the model pays greater attention to rare classes, improving sensitivity without excessively penalizing majority class predictions [124].

-

• Hybrid Approaches: Combining augmentation, synthetic generation and class weighting can yield stronger results. For example, oversampling minority classes followed by applying focal loss has been shown to enhance detection of rare Plasmodium species across different datasets [2].

-

5.6. Practical Deployment in Field and Resource-Constrained Environments

-

5.7. Data Augmentation and Image Quality Variations

These strategies not only improve classification accuracy but also enhance the clinical applicability of deep learning systems, especially when deployed in regions where the prevalence of malaria species varies geographically. Future research should focus on systematically benchmarking these techniques to identify the most effective approaches under diverse real-world conditions.

Although most studies on deep learning for malaria detection report high accuracy under controlled conditions, real-world deployment presents unique challenges. Field settings often involve limited computational resources, unstable electricity supply and inconsistent internet connectivity, all of which restrict the feasibility of complex deep learning models. Furthermore, blood smear slides in rural clinics may be poorly prepared or imaged using low-cost smartphone microscopes, introducing noise and variability not represented in standard datasets.

Several efforts have begun addressing these issues. For example, lightweight CNNs such as MobileNet and SqueezeNet [125, 126] have been adapted for smartphone-based diagnosis in low-resource settings [6, 15]. These models balance accuracy with efficiency, enabling offline inference without requiring high-end GPUs. In addition, approaches combining transfer learning with on-device optimization have shown promise for deployment in rural laboratories lacking specialized equipment.

Nevertheless, systematic evaluations of these models in actual clinical workflows remain scarce. Few studies provide longitudinal field trials or direct feedback from healthcare practitioners on usability, interpretability and integration into existing diagnostic protocols. This gap underscores the need for translational research that validates algorithms not only in silico but also in operational environments representative of malaria-endemic regions.

Image quality is a critical factor in malaria detection, as variations arise from differences in blood smear preparation, staining protocols, imaging equipment and lighting conditions. These inconsistencies often degrade model performance, especially when trained on datasets with limited variability. Data augmentation offers a practical approach to simulate such conditions and improve model robustness.

Common augmentation techniques include rotation, flipping, scaling and cropping, which introduce spatial variability and help models generalize to different smear orientations. More advanced methods, such as adding Gaussian noise, blurring and color jittering, mimic real-world degradations like poor focus, uneven staining, or low-resolution imaging from smartphone-based microscopes. For instance, Rajaraman et al. [35] applied augmentation strategies to balance imbalanced datasets and enhance performance across heterogeneous imaging conditions.

By artificially expanding the training data to include realistic imperfections, augmentation reduces overfitting to pristine laboratory images and equips models to handle noisy, low-quality inputs common in resource-limited field settings. This makes data augmentation an essential step for bridging the gap between controlled experimental datasets and operational clinical deployment.

6. Deep Learning Architectures for Malaria Detection

Deep learning architectures, particularly CNNs, have emerged as powerful tools in automating malaria detection by analyzing blood smear images with remarkable accuracy and efficiency. This section explores the state-of-the-art architectures, their performance across various datasets and their applicability in diverse diagnostic contexts, emphasizing the balance between computational requirements and diagnostic precision.

-

6.1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

CNNs have become the backbone of malaria detection systems due to their ability to extract spatial hierarchies of features from images. Prominent architectures include:

-

• ResNet: The ResNet family, particularly ResNet-50, is widely used for its skip connections that mitigate vanishing gradient issues and improve training performance. ResNet-50 achieves an impressive accuracy of 97% for malaria detection tasks, making it highly reliable for precise diagnostic applications [36].

-

• VGG: VGG16 and VGG19 offer deep yet simple convolutional layers, excelling in feature extraction for thin blood smear images. VGG16 demonstrates strong performance with an accuracy of 96%, suitable for clinical diagnostic workflows [2].

-

• YOLO: The “You Only Look Once” (YOLOv4) models are employed for real-time object detection, identifying infected cells with high speed and accuracy. YOLOv4 achieves a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 94%, making it ideal for large-scale, rapid malaria screening programs [3].

-

• MobileNet: This architecture emphasizes lightweight design and efficient computation, achieving inference times of less than one second. Its compact structure makes it well-suited for mobile applications in low-resource settings [67].

-

• InceptionV3: Known for its inception modules, this architecture achieves 95% accuracy, particularly excelling in transfer learning tasks where pre-trained models are fine-tuned on smaller malaria datasets.

-

• DeepMCNN: By incorporating expert-driven features, this model achieves a sensitivity of 92%, providing comprehensive diagnostic capabilities suitable for detecting varying parasite densities [15].

-

6.2. Transfer Learning Models

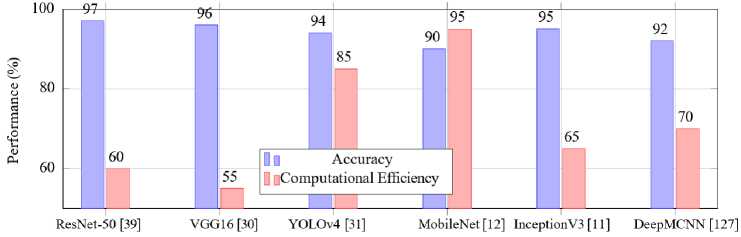

While high-performing models like ResNet-50 and VGG16 achieve top-tier accuracy, their computational complexity makes them resource-intensive. On the other hand, lightweight models such as MobileNet prioritize speed and adaptability, albeit with a minor trade-off in accuracy. YOLOv4 strikes a balance by delivering high accuracy and real-time detection capabilities, making it a popular choice for field deployments.

To illustrate these trade-offs, Fig. 11 compares the accuracy and computational efficiency of selected architectures. The comparison highlights how different models align with specific malaria detection applications, balancing precision, speed and hardware requirements.

Table 7. Comparison of deep learning architectures for malaria detection

|

Architecture |

Key Feature |

Performance Metric |

Application Context |

|

ResNet-50 [39] |

Skip connections |

Accuracy: 97% |

General detection |

|

VGG16 [61] |

Deep convolutions |

Accuracy: 96% |

Thin blood smears |

|

YOLOv4 [31] |

Real-time detection |

mAP: 94% |

Thick blood smears |

|

InceptionV3 [12] |

Inception modules |

Accuracy: 95% |

Transfer learning |

|

DeepMCNN [127] |

Expert-driven features |

Sensitivity: 92% |

Comprehensive diagnosis |

|

MobileNet [7] |

Lightweight design |

Inference time: < 1 s |

Mobile applications |

Fig.11. Accuracy and computational efficiency of deep learning models for malaria detection

Among the transfer learning models, InceptionV3 stands out with an accuracy of 95%. Its inception modules allow for the efficient learning of spatial hierarchies, making it an effective choice for malaria detection tasks [35]. Similarly, Xception, utilizing depthwise separable convolutions, offers enhanced performance by minimizing computational costs while preserving accuracy [107]. DenseNet with its dense connectivity between layers, ensures feature reuse, further improving detection rates in complex datasets [10].T he chart also highlights other architectures like ResNet and VGG which achieve 97% and 96% accuracy, respectively, due to their advanced feature extraction capabilities. YOLO and MobileNet demonstrate the potential for real-time and mobile-based applications, ensuring scalability in resourcelimited settings. The diverse performance metrics underscore the adaptability of transfer learning models across various operational contexts, reinforcing their pivotal role in advancing malaria diagnostics.

-

6.3. Hybrid and Ensemble Models for Malaria Detection

While conventional deep learning models, such as CNNs, have achieved remarkable performance in malaria parasite classification, recent studies highlight the benefits of combining multiple architectures or methodologies to overcome their inherent limitations. Two promising directions are hybrid and ensemble models.

-

A. Hybrid Models

Hybrid approaches integrate deep learning with complementary techniques, such as traditional image processing, handcrafted feature extraction, or multimodal data fusion. For instance, Masud et al. [15] and Jiang et al. [32] proposed systems where CNN-based feature extractors were coupled with classical classifiers (e.g., SVM, random forests) to enhance robustness and reduce computational cost. Such architectures leverage CNNs’ ability to capture spatial and morphological patterns while incorporating domain knowledge through handcrafted features, improving interpretability and adaptability to varying imaging conditions. In practice, hybrid models are preferred in resource-limited or heterogeneous settings where relying solely on end-to-end deep learning may lead to overfitting or degraded performance.

-

B. Ensemble Models

Ensemble methods combine predictions from multiple models to achieve higher accuracy and stability compared to single architectures. Khan and Alahmadi [128] introduced the Deep Boosted and Ensemble Learning (DBEL) framework, which integrates residual CNNs with ensemble machine learning classifiers. This approach improved discrimination in parasite detection by reducing variance and capturing diverse feature representations. Similarly, ensemble strategies that fuse outputs from models trained on different datasets or architectures have demonstrated superior sensitivity and specificity [2, 35].

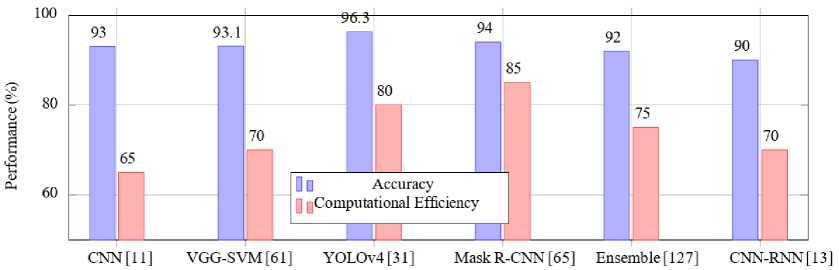

Fig.12. Accuracy and computational efficiency of hybrid and ensemble learning approaches for malaria detection

Table 12 shows the accuracy and computational efficiency of various hybrid and ensemble learning approaches for malaria detection, highlighting their performance metrics and suitability for resource-constrained environments.

-

• Ensemble Learning: Ensemble methods combine predictions from multiple models to improve robustness and reduce variance. For example, the integration of VGG-19 and SqueezeNet architectures demonstrated enhanced performance in malaria detection tasks, achieving a sensitivity of 97.3% and specificity of 96.8%. This combination effectively addressed the variability in image quality across different datasets, as noted by [30, 31]. However, these methods can incur significant computational costs, especially during model training and inference [127].

-

• Hybrid Approaches: Hybrid methods integrate CNNs with machine learning classifiers such as support vector machines (SVMs). For instance, a CNN-SVM hybrid approach achieved an accuracy of 95.8% on a dataset of thin blood smear images by leveraging the feature extraction capabilities of CNNs and the classification power of SVMs [13, 61]. This combination is particularly effective in distinguishing parasitized and uninfected cells, especially when datasets are limited in size or exhibit class imbalance [11, 37]. Kapoor and al. (2020) [46] utilized a hybrid model combining ResNet for feature extraction with a gradient boosting classifier. The approach achieved 98.2% accuracy, demonstrating the potential of hybrid methods to handle complex image data effectively. Masud and al. (2020) [15] explored an ensemble of Inception-v3 and MobileNet for malaria detection on the NIH dataset [72]. This ensemble approach improved recall to 98.5%, crucial for minimizing false negatives in diagnostic settings.

Table 8. Performance of hybrid and ensemble learning approaches for malaria detection

|

Methods |

Accuracy (%) |

Key Insights |

|

VGG-19 + SqueezeNet Ensemble [8] |

97.3 |

High sensitivity and specificity, suitable for diverse datasets. |

|

CNN–SVM Hybrid [37] |

95.8 |

Effective in handling class imbalance, suitable for small datasets. |

|

ResNet + Gradient Boosting [46] |

98.2 |

Robust feature extraction, handles complex data. |

|

Inception-v3 + MobileNet Ensemble [15] |

98.5 |

Enhanced recall, ideal for minimizing false negatives. |

C. Advantages Over Standalone Models

6.4. Novel and Custom Architectures

7. Comparative Analysis of Deep Learning Approaches7.1. Performance Comparison Across Models

The main advantage of hybrid and ensemble designs lies in their ability to address dataset variability, class imbalance and generalization issues. By combining heterogeneous learning paradigms or multiple learners, these models mitigate overfitting and improve resilience to noise or distribution shifts across geographical settings. As a result, hybrid and ensemble approaches often outperform standalone deep learning models in terms of accuracy, robustness and clinical applicability, making them particularly relevant for real-world malaria detection deployments.

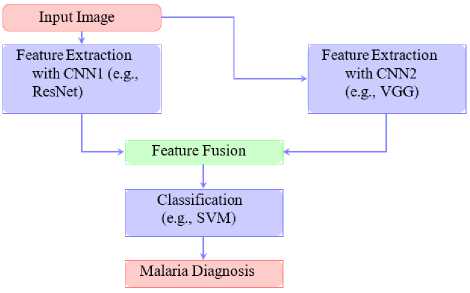

In this section, we propose a hybrid and ensemble approach for malaria detection illustrated by Fig. 13 . It shows the integration of multiple CNN models and a classification mechanism for robust diagnosis. Novel and custom architecture have been specifically tailored to meet the unique challenges of malaria detection. These models often combine advanced feature extraction techniques with domain-specific adjustments to enhance performance and usability.

One prominent example is the Deep Malaria Convolutional Neural Network (DeepMCNN) [129] which integrates CNNs with expert-designed features to provide a holistic approach to malaria diagnosis. By leveraging domain knowledge, this architecture improves detection accuracy and ensures comprehensive diagnostic capabilities. Additionally, MobileNet variants have been developed for real-time detection and efficient deployment on mobile devices. These lightweight models are optimized for resource-limited settings, enabling malaria detection in remote and underserved regions [6].

As depicted in Fig. 13, the approach begins with feature extraction using multiple CNN architectures, such as ResNet and VGG. The extracted features are fused in a decision-making step before being passed to a classification mechanism, such as an SVM. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of different CNN models while addressing specific constraints like computational efficiency and real-time processing. The flexibility and adaptability of such architectures make them invaluable in advancing malaria diagnostics in diverse operational contexts.

The application of deep learning in malaria detection has led to the development of diverse architectures, each with unique strengths and limitations. This section provides a comparative analysis of these approaches, focusing on their performance across publicly available datasets, computational complexity and suitability for various diagnostic scenarios.

A wide variety of deep learning models have been applied to malaria detection with varying levels of performance. Table 9 shows the performance comparison of Deep Learning Models on Malaria Detection. Models like ResNet-50 and DenseNet exhibit high accuracy due to their deep feature extraction capabilities, while lightweight models such as MobileNet prioritize speed over accurac y [12, 13]. Additionally, hybrid and ensemble approaches, like Mask R-CNN and VGG19-SVM, leverage specific task optimizations to improve performance metrics [61, 65]. For instance:

-

• ResNet-50 achieves an accuracy of 97% on the NIH datase t [12].

-

• DenseNet demonstrates robust performance with an AUC of 0.994 on a public malaria dataset [13].

Fig.13. Flow diagram of hybrid and ensemble approach for malaria detection

-

• YOLOv4-MOD, designed for small object detection, achieves an accuracy of 96.3% on a custom thick smear dataset [31].

-

• VGG19-SVM combines transfer learning and SVM to achieve a classification accuracy of 93.1% [61].

-

• InceptionV3 maintains a strong balance with 95% accuracy and an AUC of 0.98 on thin blood smear images

-

• MobileNet, optimized for mobile platforms, delivers a trade-off with 90% accurac y [11].

-

• DeepMCNN achieves a clinically relevant accuracy of 92% on urban health center datasets [127].

-

• Hybrid Mask R-CNN excels in instance segmentation tasks with 94% accuracy and an AUC of 0.985 [65].

-

7.2. Impact of Dataset Characteristics on Performance

These results highlight the strengths and limitations of different models, emphasizing the importance of selecting the right architecture based on application requirements, such as accuracy, computational efficiency, or deployment constraints.

Table 9. Performance comparison of deep learning models on malaria detection

|

Models |

Accuracy (%) |

AUC |

Dataset Used |

|

ResNet-5 0 [12] |

97 |

0.993 |

NIH Dataset |

|

DenseNe t [13] |

96.7 |

0.994 |

Public Malaria Dataset |

|

YOLOv4-MOD [31] |

96.3 |

- |

Custom Thick Smear Dataset |

|

Hybrid Mask R-CN N [65] |

94 |

0.985 |

Annotated Blood Smear Dataset |

|

VGG19-SVM [61] |

93.1 |

0.978 |

Malaria Digital Corpus |

|

InceptionV3 [9] |

95 |

0.98 |

Thin Blood Smear Images |

|

Ensemble CN N [11] |

93 |

0.975 |

Multiple Malaria Datasets |

|

MobileNe t [11] |

90 |

0.92 |

Resource-Limited Dataset |

|

DeepMCN N [127] |

92 |

0.976 |

Urban Health Center Dataset |

|

Hybrid CNN-RN N [13] |

90 |

0.93 |

Annotated Parasite and WBC Dataset |

|

Faster R-CN N [13] |

94.5 |

0.97 |

Annotated Blood Smear Dataset |

|

YOLOv3 [31] |

94 |

- |

Malaria Image Database |

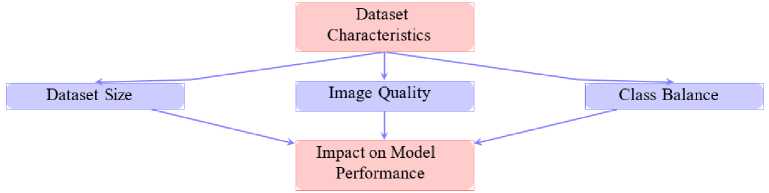

The performance of deep learning models significantly depends on dataset characteristics. Fig. 14 shows the relationship between key dataset characteristics and their impact on model performance for malaria detection. Dataset characteristics, such as image quality, dataset size and class balance, are critical determinants of the efficacy of deep learning models. High-quality images, like those provided by the NIH dataset, ensure that the models can extract intricate features, thereby enhancing performance metrics like accuracy and recall [8].

Dataset size also plays a pivotal role in the robustness of a model. Larger datasets enable models to learn a more comprehensive representation of data variability, leading to improved generalizability. However, imbalanced datasets, where one class dominates over others, can introduce biases in predictions. To address this, data augmentation techniques are often applied to balance class distributions and improve model fairness [35]. Moreover, diverse datasets that encompass variations in imaging conditions, geographical locations and patient demographics ensure that models perform well across real-world scenarios [2].

Fig.14. Impact of dataset characteristics on model performance

-

7.3. Computational Complexity and Resource Requirements

Deep learning models vary significantly in their computational complexity and hardware requirements. Table 10 provides an updated overview of the computational demands and hardware requirements of various deep learning models for malaria detection. These models span a wide range of training times and hardware needs, reflecting their architectural complexity and targeted applications.

Deep architectures such as ResNet-50 [39] and DenseNet [11] demand high-end GPUs, like the NVIDIA A100, for efficient training with training durations ranging from 10 to 15 hours. Their extensive layer depth and memory consumption make them ideal for high-performance computing environments. Similarly, InceptionV3 [13] with its inception modules designed for computational efficiency, requires high-end GPUs but has slightly shorter training times of 8 to 10 hours.

Ensemble and hybrid models, such as Hybrid Mask R-CNN [65] and Deep Ensemble [127], are computationally intensive with training times exceeding 15 hours. These models benefit from parallel processing on multiple GPUs, making them suitable for scenarios demanding high accuracy and segmentation capabilities.

YOLOv4 [45] and its modified variant YOLOv4-MOD [31] strike a balance between computational efficiency and performance, requiring mid-tier GPUs like the GTX 1660 or RTX 2080 with training times of 5 to 8 hours. These models are particularly valuable for real-time detection tasks, owing to their high-speed processing capabilities.

Lightweight models, such as MobileNet [12], stand out for their versatility in low-resource environments. Designed for deployment on CPUs or smartphones, MobileNet achieves competitive performance with minimal training times of 2 to 3 hours. This makes it an excellent choice for resource-constrained settings, such as remote or low-income regions.

This diverse spectrum of hardware requirements, training times and operational efficiencies underscores the adaptability of these models to a wide array of deployment scenarios, from high-end research facilities to field applications in resource-limited settings.

Table 10. Computational complexity and resource requirements for malaria detection models

|

Models |

Training Time (hrs) |

Hardware Requirements |

|

ResNet-50 [39] |

10-12 |

High-end GPU (e.g., NVIDIA A100) |

|

DenseNet [11] |

12-15 |

High-end GPU |

|

YOLOv4 [45] |

5-8 |

Mid-tier GPU (e.g., GTX 1660) |

|

YOLOv4-MOD [31] |

6-8 |

High-end GPU (e.g., NVIDIA RTX 2080) |

|

InceptionV3 [13] |

8-10 |

High-end GPU |

|

MobileNet [12] |

2-3 |

CPU or Smartphone |

|

Hybrid Mask R-CNN [65] |

10-12 |

High-end GPU (e.g., NVIDIA A100) |

|

VGG-SVM [61] |

5-7 |

Mid-tier GPU |

|

Deep Ensemble [127] |

15-20 |

Multiple GPUs for parallel processing |

|

Hybrid CNN-RNN [13] |

10-12 |

High-end GPU |

|

Faster R-CNN [7] |

8-12 |

High-end GPU |

|

DeepMCNN [127] |

8-10 |

High-end GPU |

8. Challenges and Future Directions

The application of deep learning in malaria detection has demonstrated significant potential, yet several challenges persist that limit its widespread adoption in clinical and real-world settings. This section explores key obstacles, including data quality, model generalization and interpretability while proposing future directions to advance the field and enhance its impact on global health.

-

8.1. Data Quality and Augmentation Needs

-

8.2. Model Generalization and Robustness