A Word about the "Russian North" Concept

Автор: Lukin Yu.F.

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Reviews and reports

Статья в выпуске: 48, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The purpose of the review is to study the essence of the concept “Russian North” in the available written sources and in various branches of scientific knowledge. The historical process of the article is localized in a vast space from the Velikiy Novgorod, the Novgorod Veche Republic to Karelia, the coasts of the White and Barents Seas — the Arkhangelsk and Kola North, the NorthEast (Komi). The Russian North is understood as a hybrid concept that requires interpretation of economics, politics, society, culture, archeology, history, geography, ethnology, ethnography, philosophy, philology and other branches of scientific knowledge. The conceptual content is associated with modern understanding of historical evolution from the past to the present as a result of the thesaurus of knowledge accumulated over centuries.

Russian North, Novgorod Veche Republic, archeology, image-geographical map, historical and cultural groups, cultural space, civilizational wave

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148329257

IDR: 148329257 | УДК: [94:902:904:913:930.85](470.1/.2)(045) | DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2022.48.275

Текст научной статьи A Word about the "Russian North" Concept

The Russian North, firstly, was not always Russian. Ancient people have long explored the vast northern space, which later became known as the “Russian North” in Russia’s history. The developed and settled northern space historically includes both the primordial ecumene and the ecumene of the Russian North. The primitive ecumene chronologically covers the time of the multi-thousand-year era of the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic. The migrations of ancient people were largely determined by changes in the natural-climatic, geophysical conditions of their habitat, the duration of interglacial periods, and directly in the Far North, by the Arctic weather conditions. Population increased during the Neolithic, when the ecumene of the northern taiga, along the banks of rivers and forest lakes, were settled by permanent population. Well-known artefacts, in fact the most ancient works of art, confirming the occupation of ancient people, are the petroglyphs of Lake Onega and the White Sea. These are images of animals, birds, fish, boats, people, signs, carved on the surface of coastal granite rocks, dating back to the 4th-3rd centuries B.C. The habitation of the northern space by the Slavs, the Russian ethnos and its transformation into the ecumene of the Russian North took place in the second millennium A.D.

Secondly, in the scientific and methodological sense, the assessment of certain historical concepts, the terminology is given by time itself, making the necessary correction in the history of the most ancient eras, which can look completely different than in antiquity, or even in the 20th

∗ © Lukin Yu.F., 2022

century. It does not matter whether this or that concept, for example “Russian North”, was or was not used in the available written historical sources: annals, acts, charters and other documents, in scientific publications of previous years. In the scientific sense, it is not only a question of terminology, but also the essence of conceptual content, coupled with a modern understanding of historical evolution from the past to the present as a result of the thesaurus of knowledge accumulated over the centuries.

Thirdly, a comparative analysis of the Slavic ecumene of Velikiy Novgorod and Kievskaya Rus allows us to conclude that Russian statehood came from Ladoga, Novgorod, from the Russian North, and not from the southern outskirts. Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences V.L. Yanin, back in 2008, was one of the first to speak publicly about the new paradigm of the entire national history. Princely power, in the aspect that relates to Novgorod, was not introduced by the spread of the political system of Kievskaya Rus to Novgorod. “On the contrary, the impetus for the unification of the Northwestern and Southern Russian lands was given not from Kiev, but from Novgorod by the famous campaign of Oleg in 882, when Kiev was conquered by the Novgorod prince, who moved his residence there.” V.L. Yanin, on the basis of the scientific facts, singled out two main cores of statehood — Kiev and Novgorod [1, Yanin V.L., p. 10]. The history of a single ancient Russian state in Kiev has a shorter chronological period than the history of Velikiy Novgorod, the Novgorod Veche Republic, as the core, organic part and beginning of the Russian land since the time of Rurik, ensuring its security and protection 1. In the 12th-15th centuries, the Novgorod Veche Republic represented a higher type of the state power and administration of that time. The most difficult period of the formation of Russian statehood was objectively connected with the permanent defence against Viking expansion and the northern crusades against Orthodoxy on the Novgorod and Pskov Veche Republics. In 13th-15th centuries, for the Novgorod Veche Republic, as well as for all Russian lands, the Grand Duchy of Moscow, the military-political threat from the East increased sharply.

Fourthly, in the scientific literature, the conceptual definition of the “Russian North” by scientists of various specialties and directions is usually interpreted depending on their goal and motivation, the subject and object of research, and the branch of scientific knowledge. Exploring the scientific literature on the Russian North, one can confidently interpret its concept as a kind of hybrid concept that requires understanding of the economy, politics, society, culture, archeology, history, geography, ethnology, ethnography, philosophy, philology and other branches of science. In modern scientific research, there are concepts not only of the “Russian North”, but also “European North of Russia”, “North of Europe”, “Arkhangelsk North”, “Kola North”, “Far North”, “Dvina Land”, “Zavolochye”, “Pomorye” and others, chronologically related to the second millennium A.D. Slavs appeared in the north in the 10th-11th centuries, and for several hundred years, they pushed the borders of Ancient Russia to the White Sea, the lower reaches of the Northern Dvina and hundreds of miles to the northeast. As a matter of fact, this is actually the initial chronological stage of the formation of the historical and cultural group of the future Russian world at the beginning of the second millennium of the new era. Without claiming to provide a complete review of all available concepts, discussions on this issue, this article only partially explores this topic.

Archeology of the Russian North

The concept of “Russian North” is used in archeology, although its conceptual definition appeared and was fixed in the scientific literature much later. The formation of archaeological science in the Arkhangelsk province, the contribution of the founders of the archeology of the region — A.G. Tyshinskiy, P.S. Efimenko, K.P. Reva, V.I. Smirnov — are studied in the article of the candidate of historical sciences, archaeologist A.G. Edovina [2, pp. 6–14]. The publication of the work “Zavolotskiy Chud” by ethnographer Pyotr Savvich Efimenko (1835–1908) is associated with the beginning of archaeological science in the Arkhangelsk province.

In the 20th-21st centuries, the archeology of the Russian North, including the Arkhangelsk North, Karelia, the Kola North, the European Northeast (Komi), was carried out by A.E. Belichenko, V.A. Burov, I.V. Vereshchagin (1947–2006), N.N. Gurina (1909–1990), A.G. Edovin, V.I. Kanivets (1927–1972), A.A. Kuratov (1936–2014); N.V. Lobanova, N.A. Makarov, A.Ya. Martynov, O.V. Ovsyannikov, P.Yu. Pavlov, Yu.A. Savvateev, M.V. Shulgin and other scientists. Analyzing the main sources of history and culture of the Arkhangelsk North and available artifacts, professor A.A. Kuratov singled out, following M.E. Foss and A.Ya. Bryusov, the Kargopol archaeological culture, which is also widespread in the White Sea basin, the White Sea and Pechora archaeological cultures, including the world-famous islands of the Solovetskiy archipelago, as well as island cultures of the oceanic basin, sites on the islands of Kuzov, Morzhovets, Mudyug, Vaygach, Kolguev, Franz Josef Land. Doctor of Historical Sciences N.N. Gurina, exploring the archaeological sites of Karelia, the Leningrad Oblast, the Kola North, the coasts of the White Sea, made a decisive contribution to the identification of a number of archaeological cultures of the Neolithic era, including the Valday, Kola, developed a number of issues of settlement and periodization of the North-West of the European part of the USSR [3]. Interesting information about archaeological sites that have come down to us from ancient Russia is connected with diplomacy. In a long dispute with Denmark, defending the rights of Russia to the “Lop land” (Lapland), the Russian envoys I.S. Rzhevskiy and S.V. Godunov in 1603 reported to the Danish ambassadors the text of the letter stating that “ Lopskaya land is all of old to our fatherland, to Novgorod land, and a Korelian sovereign named Valit, also Varent, took it by war, and its Russian name was Vasiley, which now is in those places on the Murmansk Sea in its name the town of Valitovo and other signs, as you have been truly announced ” [4, Formozov A.A., p. 22].

Russian North, as defined by archaeologist N.A. Makarov, Director of the Institute of Archaeology since 2003 and RAS Academician since 2011, “means a vast territory, including the basin of Lake Onega in the west and the basin of the Mezen in the east, with a southern boundary running along the watershed line of the Volga and Sukhona. The Russian population of this region is characterized by a certain unity of the dialect and the traditional everyday culture. We can also talk about the unity of the historical fate of the region in the Middle Ages” [5, pp. 61–71]. The Slavs appeared there only at the turn of the 10th-11th centuries, and for several hundred years, they pushed the borders of Russia hundreds of miles to the northeast, to the White Sea and the lower reaches of the Northern Dvina. The Old Russian settlement of the North noticeably intensified in the middle of the 12th century, when things of Old Russian types spread over a vast area from Beloozero and the Volga-Sukhonskiy watershed to Finnmark and the Northern Urals. This area roughly corresponds to the concept of the zone of “Russian tributes”, outlined on the basis of chronicles, charters and other documents. On the archaeological map of N.A. Makarov of 1986, containing finds from the 10th–13th centuries, 177 sites were localized.

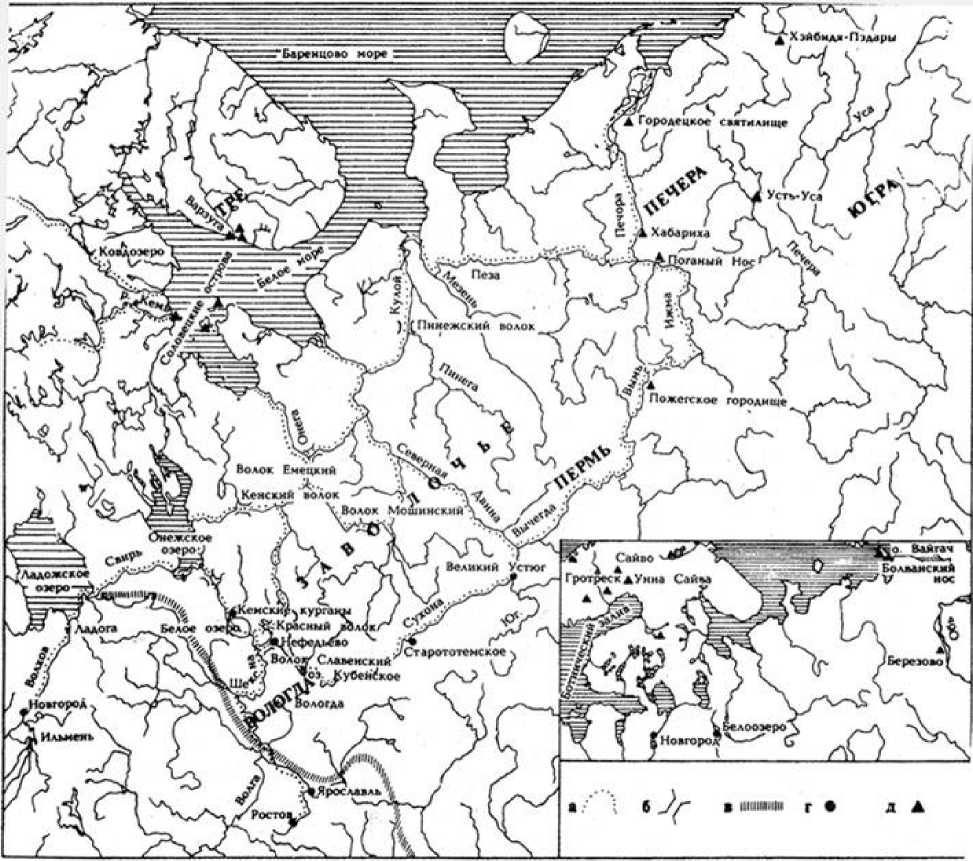

Fig. 1. Makarov N.A. Waterways of the North in the 11th-13th centuries: a - routes of waterways; 6 - floats; в -northeastern border of the zone of distribution of ancient Russian barrows; г - cities and archaeological sites of the 11th-13th centuries; д - finds of objects of ancient Russian origin in the Far North.

By 1993, the archaeological map contained over 220 points, each followed by a settlement, a burial ground, a coin hoard or an occasional find of medieval ornamentation. The monuments on the map differ in appearance, their state of preservation and their richness in antiquities. They have only one thing in common — they are material remains, firmly dated the 11th-13th centuries, evidence of a permanent or temporary stay of a person in the inhabited ecumene of the Russian North in that era. For centuries, the Svir and Sheksna remained the main gates of the North, giving rise to two waterways: Svir - Lake Onega - Onega - Northern Dvina and Sheksna - Sukhona - Northern Dvina. Analysis of the map makes it possible to assess the population of certain northern territories, the distribution of the population, and the direction of migration flows. The social structure of the population of the ecumene of the Russian North is examined by N.A. Makarov in the monograph “Russian North: the mysterious Middle Ages”, where the indicated map was published. In fact, this is one of the well-known maps of the ecumene of the future Russian North of the 11th-13th centuries, scientifically substantiated, based on artifacts, material and written primary sources, which has no analogues in Russian history.

The 11th-13th century chronicles contain references to princes and free communes, dru-zhinniks and smerds, pagan magi and Orthodox priests. Archeology makes it possible to substantively understand the ethnic picture of settlement, the Chud heritage, traces of the Scandinavians, the culture and rituals of ancient people. N.A. Makarov gave a description of the funeral rite, regarding it as Christian. In the 11th-12th centuries, the population of Belozerye and Kargopol no longer burns their dead, as the Slavs and Finns did at the end of the first millennium A.D. Like the inhabitants of most other regions of Ancient Russia, the northerners bury the dead. The change in the rite is undoubtedly the result of the influence of Christianity. Under its influence, the funeral rite is gradually changing, clearing itself of pagan elements. The absence of princely towns and fortresses in the North is indicative. All graveyards named in the charter of 1137 and surveyed by the expedition of N.A. Makarov, turned out to be unfortified. The need for protection was not as acute in the North as in the southern and central regions, which more often became the scene of hostilities. If we compare the North with the conquest of Siberia, then in thirty years, it has passed from the Yermak’s detachment arrived on the Irtysh until 1618, when the annexation of Western Siberia to Russia was basically completed, 14 cities and prisons were built on the new lands by the efforts of the government, and for a hundred years — about 150 fortifications. In the North, for 250 years, starting with the penetration of the first colonists in Zavolochye and ending with the Batyev invasion, only three cities were founded: Beloozero (redevelopment in 1170), Gleden (1178) and Velikiy Ustyug (1212). Exploring the problem of “Man and the State”, N.A. Makarov noted that the monks who left the rich monasteries of Moscow, Rostov and Novgorod in the 14th-15th centuries, went to the North in search of deserted places, solitude. The walls of suburban monasteries could not protect them from too close contact with the secular and spiritual authorities, the proximity of which guaranteed material prosperity, but deprived them of independence. For all set-

REVIEWS AND REPORTS

Yury F. Lukin. A Word about the "Russian North" Concept tlers, “solitude” was synonymous to “freedom”, which meant a “hidden” existence, but if not complete, then relative isolation. This, by the way, was well known to my ancestors [6, Kuznetsova V.P.].

A significant contribution to the archeology and history of the Russian North was made by Doctor of Historical Sciences O.V. Ovsyannikov. As a result of intensive searches on the banks of the rivers Vaga and Tikhmanga, Varzuga and the Northern Dvina, on the Terskiy coast of the White Sea, burial grounds and treasures of the late 11th–13th centuries, left by the Finnish-speaking aboriginal population and the ancient Russian pioneers, were discovered and investigated. The Arkhangelsk treasure, discovered in 1989, 40–45 km up the Northern Dvina from its confluence with the White Sea, included 1915 coins (more than 90% of them were German minted in the 10th– 12th centuries) and about 20 pieces of jewelry, including Old Russian and Scandinavian manufacture. This treasure on the Vikhtui River dates back to the 1130s. Perhaps, there was an ancient settlement in the mouth of the Northern Dvina River. The study of Orletskiy, Vazhskiy, Yemetskiy, Varenga, Votlozhma, Kevrola, Topsy and other northern towns made it possible to substantiate their dating of the 14th–15th centuries, to show that these were rural fortified patrimonial centers (boyar estates). In collaboration with M.E. Yasinskiy, O.V. Ovsyannikov published a monograph “A look at the European Arctic: the Arkhangelsk North: problems and sources” in two volumes [7]. He took part in the famous Mangazeya historical and geographical expedition led by M.I. Belov in 1981.

A review of the archaeological study of the Finno-Ugric and Slavic settlements, the study of the ethno-political situation in the north of Russia, was carried out by the largest researcher in the archeology of the Finno-Ugric peoples of Ancient Russia, Doctor of Historical Sciences E.A. Ryabinin (1948–2010). His work is based on the use of archaeological sources accumulated over 150 years of active study of the Finno-Ugric and Old Russian monuments. E.A. Ryabinin comprehensively studied the Finno-Ugric population of the Northern Dvina (on the problem of studying the Zavolochskaya Chud). He gave an overview of the history of the issue, analyzed in detail the available sources, found artifacts, scientific literature. Considering the concept of settlement of Zavolotskaya Chud in the lower reaches of the Northern Dvina, the scientist noted the identification of this area with Bjarmia of Scandinavian sources, mentioned since the end of the 9th century, considered archaeological data on ethnocultural processes in Zavolochye. The problem of Chud assimilation in the era of mass colonization of Zavolochye in the conditions of a lack of archaeological knowledge, according to E.A. Ryabinin, is solved mainly using information on history, ethnography, linguistics, anthropology [8, pp. 5–7, 113–148].

V.N. Kalutskov: figurative-geographical map of the Russian North (2018)

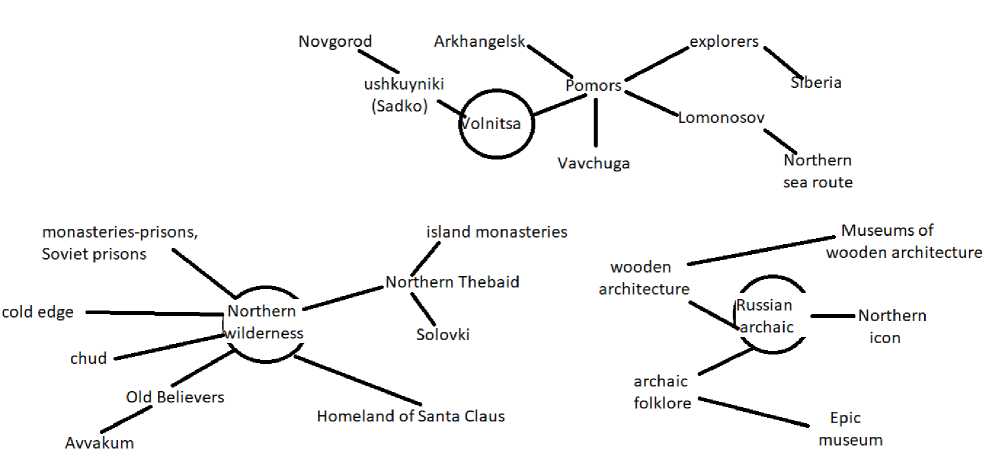

Each region of Russia has its own conceptual and geographical system, due to the uniqueness of ethno-cultural traditions and natural landscapes. Diverse topics of a series of reports on the Russian North, made at seminars at Moscow State University named after M.V. Lomonosov in 1995-1997, gave a picture of the North Russian cultural landscape. V.N. Kalutskov, Yu.A. Davydo- va, E.A. Rodionov, L.V. Fadeeva and others discussed issues at these seminars: typical landscape-toponymic situations of the Russian North, archaic spatial structures of the Russian North, sacred geography of the Russian North, folk Orthodoxy and the cultural landscape of the Russian North, ethno-cultural boundaries of the Russian North (based on the Pinezhye material), etc. Interest to the Russian North was manifested not only in the topics of reports, but also in interdisciplinary interaction with the Pomor University named after M.V. Lomonosov. In November 1996, the first round table “Cultural landscape of the Russian North” was held in Arkhangelsk within the framework of the international conference “M.V. Lomonosov and the National Heritage of Russia”, which was attended by geographers, historians, culturologists, ethnolinguists, folklorists and teachers of higher and secondary educational institutions from Arkhangelsk, Moscow, Murmansk, Pinezhskiy district. In 2009, Doctor of Geographical Sciences, Professor V.N. Kalutskov defended a dissertation on the landscape concept and cultural geography, published the monograph “Landscape in cultural geography” (2008), a number of articles on the Russian North: Regional cultural landscape and its cycles (2005), Cultural and landscape zoning of the Russian North: statement of the problem (2007), Russian North and its age-old geopolitical trends (2010), On the geoconcept of the Russian North (2011). An analysis of the humanitarian studies of the region, carried out by prominent scientists, allowed V.N. Kalutskov to identify the most typical complex characteristics, which include: remoteness, the outlying position of the Russian North, the absence of serfdom and landowners, harsh natural conditions, the North Russian housing complex, poor development of the territory, a complex type of peasant economy, polyethnicity with the leading role of Northern Russian traditional culture, Northern Russian dialects, Old Believers and folk Orthodoxy. The author’s figurative map of the Russian North by V.N. Kalutskov is based on three main concepts: volnitsa, northern wilderness, Russian archaic [9, Kalutskov V.N.].

Fig. 2. V.N. Kalutskov: figurative-geographical map of the Russian North (2018).

Historical and cultural groups of the Russian nation

The Russian nation is characterized by a unity of language, a great community of material and spiritual culture. However, such unity does not exclude regional differences, and some of them go back in their basis to deep antiquity, as it was emphasized in the section “Historical and cultural groups of the Russian people” of the first volume of “Ethnographic Essays”. The division of the population into historical and cultural groups, and not fruitless discussions around the Pomeranian identity, seems to me the best scientific approach when studying the concept of “Russian North”. The author of the above section is the largest specialist in the ethnography of the Russian people, Doctor of Historical Sciences G.S. Maslova (1904–1991) noted that peculiar historical and cultural groups arose as a result of various migrations from one region to another, the formation of a military population on the borders of the state (Cossacks, monodvortsy, etc.). She singled out the Northern, Southern, Central Russian, transitional and other groups, the Far North [10, pp. 125, 143-147].

The Northern group. Typical “northern Russian” culture and lifestyle traits and a northern “o-pronounced” dialect can be traced from the Volkhov river basin in the west to the Mezen river and the upper courses of Kama and Vyatka in the east (i.e. Novgorod region, Karelian ASSR, Arkhangelsk, Vologda, parts of Kalinin, Yaroslavl, Ivanovo, Kostroma, Gorki and other regions). In fact, this is the “Russian North”, although in the cited edition of 1964 such a term was used only in the context of the fact that the wooden architecture of the Russian North was distinguished by the richness and variety of decoration of the external parts of buildings. The northern historical and cultural group did not include the Murmansk Oblast (Kola North), the Komi Republic (northeast), the geographical space of which was developed in the 11th-15th centuries. The study of dialect differences provides interesting and valuable material for clarifying the ethnic history of the Russian people, migration processes and phenomena, as well as the problems of cultural mutual influences between the individual peoples of our country. The oldest written monuments testify that the Novgorod “ts-pronounced” dialect of the 11th-12th centuries was already characteristic, which was absent in the Kievskaya land. As part of the North Russian dialect, five groups were distinguished: Arkhangelsk, or Pomeranian; Olonets; Western, or Novgorod; Eastern, or Vologda-Kirov; and Vladimir-Volga region.

According to G.S. Maslova, the Southern group included most of the Ryazan, Penza, Kaluga, Kursk, Lipetsk, Orel, Tula, and Tambov regions. The South Russian features in culture, life and the southern “a-pronounced”dialect prevailed from the Desna River basin in the west to Penza Region in the east, and approximately from the Oka River in the north to the Khopyor and Middle Don basins in the south.

The Central Russian group occupied the territory, mainly the Volga-Oka interfluves, where the Russian principalities began to unite around Moscow in the 14th century and where the Russian nucleus of the Russian nation was forming. According to the modern administrative division, these are Moscow, Vladimir, northern Ryazan, Kaluga, parts of Kalinin, Yaroslavl, Gorkiy, Kostroma, Ivanovo and some other adjacent regions. The region of the Central Russian transitional dialect distinguished by dialectologists (along the lines of Pskov, Kalinin, Moscow, Ryazan, Penza, Saratov) is somewhat narrower than the region that stands out according to ethnographic data. The Central Russian group is a link between the northern and southern Russian populations. Its material and spiritual culture combined northern and southern features. On the other hand, many local characteristics (in clothing, buildings, customs) are widespread in the north and south.

According to dialectological and ethnographic data, a transitional group between the northern and central, central and southern Russian populations, as well as Russians and Belarusians, included the population of the ancient Russian territory in the basin of the Velikaya River, the upper reaches of the Dnepr and the Western Dvina (Pskov, Smolensk, parts of the Kalinin and other adjacent areas). In addition to the above and other large ethnographic groups and subgroups, the Russian population of Siberia, Russian Ustinians on the Indigirka River, Markovians at the mouth of the Anadyr River and other smaller, peculiar groups of the Russian population with special names or self-names were distinguished. For example, the Far North - the coast of the White Sea was inhabited by Pomors. Pomors, according to G.S. Maslova, rather a geographical than an ethnographic term and means: 1) the population of the White Sea coast from the Onega River to Kem; 2) residents of the northern sea coast.

The Pomors, who are the descendants of the ancient Novgorod settlers, are similar in their material and spiritual culture to the rest of the Russian population of the North and differ mainly in the features of their economic life; From time immemorial they have been known as brave seafarers, sea animal hunters and experienced fishermen. In general, the analysis of the historical and cultural groups of G.S. Maslova is the foundation, the scientific basis for understanding the essence of the concepts “Russian North”, “Far North”, “Siberia” and other regions of Russia both in the past and in the present.

Ethnography of the Russian North

Ethnography has accumulated a significant number of facts and concepts related to the historical evolution of the East Slavic peoples. The ethnographic study of the North began in the 18th century, at the time of M.V. Lomonosov, and continues to this day. The executive editors of the book “Folklore and Ethnography of the Russian North”, Doctor of Philology B.N. Putilov (1919– 1997) and Doctor of Historical Sciences, Corresponding Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences K.V. Chistov (1919–2007) determined “Russian North” as the northern regions of the European part of the USSR, predominantly populated by Russians. From the standpoint of ethnography — the territory, where the complex of the Northern Russian traditional household culture was spread, which by its geographical configuration is very similar to the area of the Northern Russian dialects. From the dialectological point of view, these are the areas where the speakers of the North Russian dialects lived. Well-known scientists emphasized the relevance of a detailed study of the history of the settlement of the Russian North by immigrants from the Novgorod and Rostov-Suzdal. Among the features of the development of the Russian North, without studying of which it is impossible to understand many of the processes that played an important role in the socio-economic history of our country, they attributed the fact that the northern territories were not affected by the Tatar-Mongol invasion in the 13th-15th centuries, not covered by the most cruel, the landlord (privately owned), form of serfdom in the 17th-19th centuries. The North Russian regions were formed as a natural repository of folk everyday traditions and folk art culture, became famous for their wonderful examples of folk architecture, embroidery, carving, and partly painting. World-famous Russian epic songs (epics) were discovered here, a large number of ancient folk songs, lamentations and fairy tales, distinguished by their unique originality and high artistic merit, were recorded [11]. At the same time, it was emphasized that many problems of studying the history and culture of the Russian North are still waiting to be developed, which is still relevant in the first quarter of the 21st century.

In 1948–1960, professor K. V. Chistov organized and headed numerous scientific expeditions to study the folk (peasant) culture of the Russian North. Among his famous students was T.A. Bernshtam (1937–2008), author of several monographs on the ethnography of the Russian North. She defined Russian North (or simply North) as the territory lying to the north of that area which the Eastern Slavs settled in primitive communal life, before part of the Eastern Slavs began to recognize themselves as Russians. The northern border of the area of dominance of the Eastern Slavs passed to the east from the southern part of Chudskoe Lake by the 9th century, crossed the Volkhov River, turned behind the Meta River to the southeast, crossing the upper reaches of the Volga River, reached the Oka River west of Murom. Further, to the east, this border can be conditionally continued along the right bank of the Oka and Volga rivers, along the lower reaches of the Kama, Belaya and Ufa rivers to the Ural Mountains. The eastern border of the western part of the Russian North can be drawn from the confluence of the Oka and the Volga, through the lower Vychegda and along the Mezen River to the White Sea. As a result of numerous expeditions in the Russian North (Arkhangelsk, Murmansk, Vologda oblasts, Karelia) in the 1960s–1990s, Tatyana Alexandrovna collected significant field materials, which later formed the basis of the collections “Russian North” on the problems of ethnocultural history, ethnography and folklore, the cultural tradition of local groups, other aspects of the unique in ethno-cultural history and folk tradition [12].

The traditional culture of the Russian North is the subject of a monograph, dissertation of Doctor of Philology and other scientific works, professor N.V. Drannikova. Her research is based on records made during expeditions in the Russian North and North-West of Russia (Arkhangelsk, Vologda, Kirov, Murmansk, Novgorod oblasts, Karelia and the Komi Republic). The historical and cultural memory of the society is an integral part of the local identity [13].

Russian North in the history of Russia

The history of ancient people who explored the coast and islands of the White, Barents and

Baltic Seas, includes a significant list of knowledge both in available sources and in the scientific literature. The Slavic language has come a long way of development within the framework of an older and more extensive linguistic community — the Indo-European: “with a certain probability related to the 5th-4th millennia B.C., to a certain spatially limited locus (“ancestral home”), to specific archaeological culture”, emphasized Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences V.N. Toporov (1928–2005) [14, pp. 49-50].

Velikiy Novgorod historically became the cradle of the future Russian North in the first millennium A.D. Rurik came to Lake Ilyimen, founded the city over the Volkhov River and called it Velikiy Novgorod. The mention of Slovenians, Gostomysl (790-860) near Lake Ilmen, the name “Rus”, is found in “About Velikiy Novgorod and Russia” of the Ipatievskaya and Voskresenskaya annals. The arrival of Rurik and his brothers was described by Nestor of Kiev (1056–1114) in The Tale of Bygone Years, the date of its writing was about 1110–1118, but the original has not been preserved. The author of the Joachim Chronicle was the first Bishop of Novgorod, Joachim Korsunya-nin (992-1030). At the request of the Grand Duke Vladimir, the Patriarch of Constantinople from 979 to 991 Nicholas II Chrysoverg sent to Russia several clergymen, among whom was Joachim. Later Russian chronicles of the 14th-16th and even 17th centuries recorded the subsequent stages of the development of the northern lands and its final settlement by the end of this period 2. The Tale of Bygone Years and other chronicles mention Chud, Perm, Pechora, Yugra, Korela, Lop, Samoyed, Toymokars among the peoples inhabiting the northern lands all 3.

Professor S.N. Azbelev (1926–2017) carefully analyzed the information about Gostomysl, who was known not only from Russian chronicles, but also from Western European chronicles of the 9th century, as the king of the obodrite state [15, pp. 381-392]. He also studied the annals of Velikiy Novgorod, chronicles of the 11th–17th centuries as cultural monuments and as historical sources. “Rus” is an older word than “Varyagi,” emphasized Doctors of Historical Sciences D.S. Raevskiy (1941–2004) and V.Ya. Petrukhin [16].

Doctors of Historical Sciences V.O. Klyuchevskiy (1841–1911), D.S. Likhachev (1906–1999), K.A. Nevolin (1806–1855), S.M. Solovyov (1820–1879), V.L. Yanin (1929–2020) and other scientists have made an important contribution to the history of Velikiy Novgorod, to the development of its statehood. Analyzing the Icelandic sagas, A.A. Vasilyev tried to create an ancient history of Northern Russia without the Varangians in the middle of the 19th century. He, as M.V. Lomonosov did before, criticized the Norman theory, argued that the Varangians were Slavs as Russ, cited the names of the country found in foreign sources: Russi, Russia, Rugia, Ruthenia, Risaland. For many centuries before Rurik, the Slavs of the North had a settled life, significance, citizenship and laws. There were wars and reconciliations; there were cities, well-organized communities. According to A.A. Vasilyev, the information about the history of the Northern Slavs had to be sought in the North, and for this reason, traditions were collected in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Prussia and Iceland. He believed that Biarmia was a strong eastern state that occupied the current Arkhangelsk, Vologda, Vyatka and Perm provinces, which became part of the Novgorod domain in the following centuries [17, p. 36]. Long before the discovery of Greenland and Vinland (America), at the time when Iceland was inhabited, the ancient Scandinavians went on their ships to the northernmost countries in the Arctic Sea, to the shores of the White Sea and rich Bjarmia, — explains Anders Magnus Strinnholm, 1786–1862, a member of the Swedish Academy of Sciences, in the tenth chapter of his work about the voyages of the Nordic peoples to Bjarmia [18]. There is historical evidence about the trip of the Normans to the White Sea, which is in the Anglo-Saxon translation of “History against the Gentiles”, authored by Paulus Orosius (about 385-420) [19]. The localization of the places visited by the Vikings caused a discussion in the scientific community, the details of which were carefully studied by Karl Tiander, G.V. Glazyrina, E.A. Melnikova, T.N. Jackson and other scientists. Toponyms were mentioned in the Scandinavian sagas: Bjarmaland — the Land of the Bjarms, Kirjalaland — the Land of the Karelians; hydronyms Gandvik — White Sea, Vina — Northern Dvina; Novgorod, Holmgard — Holmgaror; Russaland — Land of the Russians, etc. In most sagas, the mouth of the Northern Dvina River was called the final destination of the campaigns of the Scandinavians 4.

Slavic colonization from the Novgorod lands went to the Lower Dvina along the Onega River and other rivers, lakes, and then to the White Sea. The second route from the Rostov-Suzdal, Moscow princedoms passed along the Sukhona, the upper and middle Dvina. Farming, agriculture was the main occupation of the Slavs. Therefore, they settled along the banks of rivers and lakes suitable for agriculture [20, Sedov V.V., p. 236]. By the end of the 1070s, Velikiy Novgorod has already spread its graveyards in Zavolochye [21, Nasonov A.N., p. 100]. The discovery of new geographic routes, land passage to the Urals and Siberia, the collection of tribute in Zavolochye, on the Northern Dvina, Pechora, and Yugra took place in the 11th-15th centuries. Huge expanses of northern lands with a low population density of local hunters and fishermen, the development by the Slavs of the northern taiga, river valleys suitable for agriculture and cattle breeding, a higher level of culture — these and other circumstances predetermined the mostly peaceful, non-violent nature of Slavic migration to the north, in contrast to the later conquest of Siberia. The development of the ecumene of the northern lands by the Novgorodians did not lead to a clash with the

REVIEWS AND REPORTS

Yury F. Lukin. A Word about the "Russian North" Concept aboriginal population, whose main occupation was traditionally fishing and hunting. The Slavs plowed the land and cultivated cereals. Each of the ethnic groups gravitated towards different natural areas of settlement in the northern ecumene, without interfering with each other. Land passage to Pechora, Yugra, beyond the Urals, in contrast to the colonization of Zavolochye, the Dvina land, the coast of the White Sea, was not aiming at settling these distant and hostile areas, was limited to the collection of tribute. The assimilation of the Slavs with the local Finno-Ugric local tribes promoted the interpenetration of different cultures, trade, and the socio-economic development of the northern lands. The development of the northern territories by the Novgorodi-ans was distinguished by religious tolerance and was predominantly of a trade and economic nature, rather than a military one, although severe wars, typical for those times, were not excluded.

Christian Orthodoxy, parish churches, monasteries, chapels, and votive crosses played an important role in the settlement of the Slavic ecumene of the Russian North. The active Orthodox monasteries, parish churches brought beauty and holiness to life, the arrangement of the entire surrounding ecumene, as ancient centers of Christian education, writing, annals, and icon painting. Their contribution to culture, architecture, painting, art, book printing, archiving, organization of libraries is invaluable. Multifunctional Orthodox monasteries, including those in the Russian North, were not only monastic cloisters, spiritual centers of culture, Christian education and art, but also acted as defenders of the Orthodox faith. There are many examples of this in national history. Giles Fletcher (1548–1611), Doctor of Law, an English diplomat who visited Russia in 1588–1589 during the reign of Fyodor Ivanovich, called Russia a country of monasteries [22].

The scale of military attacks on the lands of Velikiy Novgorod, the Novgorod Veche Republic from the western and northwestern directions can be judged by the following very impressive figures, which were cited by Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences D. S. Likhachev in his well-known work “Essay on the history of the culture of Novgorod in the 11th-17th centuries”. Novgorodians persistently, stubbornly, courageously waged incessant defensive wars on their borders, firmly holding a shield over the entire north-west of Russia. During the period from 1142 to 1446, Novgorod fought 26 times with Sweden, 11 times with the Livonian Order, 14 times with Lithuania and 5 times with Norway. There were two main directions of foreign expansion in the 12th-15th centuries on the lands of the Novgorod Republic: western and eastern. D.S. Likhachev reasonably emphasized the exceptional importance of Novgorod for preserving the culture of the entire Russian land in the difficult years of “languor and torment of the Tatar-Mongol yoke”. The hordes of Batu did not reach Novgorod, Kholmogor and other cities in the North, which happily escaped defeat and destruction. This made it possible to develop culture, architecture, preserve the manuscript wealth of Ancient Russia, book education, fresco painting, and icon painting in the Russian North [23]. Armed conflicts, their outcome, defeats or victories, negotiations, concluded truces, certainly could not fail to affect all life activities of the Russian North ecumene.

The Crusades are an attempt to unite and expand the Christian Catholic world under the rule of the Roman papacy in the 11th-15th centuries by using force. In 1096-1270, eight crusades took place, aimed primarily at Palestine, the capture of Jerusalem with the Holy Sepulcher. The northern crusades of the Danish, German and Swedish knights were already sent to the Baltic, to the lands of Poland, Estonia, Finland, Karelia, the Novgorod and Pskov Veche republics, where there were permanent missions of Christian Orthodox churches, though not of the faith pursued by the Catholic Pope. One more specific feature of the crusades in the North was their multivector nature at the first stage, and then their insistence on punishing, ruining and subduing Slavic state formations, especially Novgorod and Pskov. In 1232, Pope Gregory IX called on the crusaders to attack the Novgorod lands. During the Livonian campaign of 1240-1242, German knights captured Izborsk and Pskov, but were defeated by the Novgorod Veche Republic. Attacks by Swedish, Lithuanian and other foreign troops on Novgorod, Pskov, and the Russian North were allegedly carried out with the aim of Christianizing ethnic tribes, converting Orthodox Slavs to Catholicism. In reality, most often their goal was colonization by force of arms, the “ordinary” seizure of foreign lands, Novgorod possessions and robbery of the population. The campaign of Magnus in 1348 was the last of the “crusades” of the Swedish knights to the lands of the Novgorod Republic. Ancient Russia, Velikiy Novgorod, Pskov were actually an integral part of the entire Christian world and a completely unanimous country by that time. Attempts of the Novgorod Veche Republic to defend its economic and political interests in the 13th-14th centuries were perceived as helping and aiding the pagans, which served as an ideological justification for the expansion of the crusaders. In fact, under the guise of Christianization, the lands conquered by the crusaders were forcibly colonized; and new towns (Riga, Berlin, Revel, Vyborg), state formations, and the holdings of the Teutonic and Livonian Holy Orders of Chivalry were being established.

According to many researchers, archaic rites, rituals and traditions have been preserved in the Russian North, which are older than the ancient Greek ones and are also recorded in the Vedas, the oldest cultural monument of the ancient Indian nations. A well-known Russian specialist in the history and culture of the Russian North S.V. Zharnikova (1945–2015) analyzed the origins of folk culture, ceremonies and holidays, fairy tales, epics, incantations, the semantics of folk costume, and the archaic roots of the Northern Russian ornament; Sanskrit roots in the topo- and hydronyms of the Russian North [24, Zharnikova S.V., pp. 57–69].

An overview of the economic and industrial life of the Russian North was carried out by A.P. Engelgard, governor of the Arkhangelsk province in 1893–1901, in the book “Russian North: Travel Notes” (1897). At the same time, the concept of “Russian North” is used only in the title of the entire book and in the general overview. There is no specific definition of this concept further in the text. Judging indirectly from the table of contents of the text, A.P. Engelgard included in the structure of the Russian North Kemskiy and Kola counties, Korela or Koreliya, Pomorie, Lapland, Murman, Novaya Zemlya, Pechora Territory, Zyryans, Samoyeds [25, pp. 1-15]. The founder of the

Pechora natural history station, researcher of the economy and social sphere of the Russian North, A.V. Zhuravskiy (1882–1914) uses the concept of “Russian North” in the context of the actual life of the Russian North, love for Russia and the Russian North on the basis of faith and service in his work “European Russian North. On the question of the future and the past of its life” (1911) [26, p. 6, 12].

The vast expanses of the northern part of the East European Plain from the shores of the Arctic Ocean to the watershed separating the left tributaries of the upper and middle Volga from the river basins of the extreme Russian North, and from the Russian-Norwegian border to the Ural Range (1919), — this might seem to be a land of harsh ruggedness, lack of appealing cultural development and promise in terms of natural resources and natural diversity. However, A.A. Kizevet-ter (1866–1933), Master (1903), Doctor of Russian History (1909), Privatdozent (1893–1909), Professor at Moscow University (1909–1911, 1917–1920), could not agree with this image in the form of a dead capital, supposedly its withering away. This territory was a part of the Russian land in the past epochs of historical life not as a motionless dead weight, attached to the Russian state organism and hindering with its weight the free disclosure of the internal forces of this organism, but as a viable nourishing cell, significantly contributing to its overall internal prosperity. In the second chapter, “The Russian North and the Novgorod State”, A.A. Kizevetter substantiated that the Russian North really attracted immigrants from Velikiy Novgorod and Suzdal land with its vast expanses, free land, natural abundance, fur and other riches, opportunities for fish and salt trade, agriculture, and entrepreneurial activities. The North abundantly supplied the inner provinces of the Moscow state with the products of its local industry, among which the most important belonged to fish (especially salmon), salt, lard, skin of sea animals and furs; almost all foreign trade of the state was concentrated in the North; The North served as the main connecting link between European Russia and Siberia in terms of trade. In the 16th-17th centuries, Muscovite Russia received abundant fruits from the industrial boom of the “Russian North”, but in the 18th century, the economic and political importance of the North began to diminish [27, Kizevetter A.A., pp. 3–4, 12– 22, 58–66].

Exploring the historical and cultural development and identity of the population, I.V. Vlasova (1935–2014), Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor, Honored Scientist of the Russian Federation, gave the following definition of the Russian North: “ The territory from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Volga-Northern Dvina watershed in the south, from Karelia in the west to the Ural Mountains in the east , although it is inhabited not only by Russians, but also by Karelians, Komi, Veps, Saami (Lapps), Nenets. In the 17th-18th centuries, there were other names for this territory: Pomorye, North, Northern Russia. Since the 19th century, the name “European North” is known, in contrast to the northern lands beyond the Ural Range [28, p. 16].

Professor V. N. Bulatov (1946-2007), Doctor of History, who comprehensively studied the mysteries of the North, published five books on the history of the Russian North and a fundamental textbook "Russian North" in the framework of the “Gaudeamus: Academic Project” in

1997-2006 [29]. His other scientific publications are also known. Among the works published by G.P. Popov (1928–2019), his works on the history of the Arkhangelsk port (1992), the governors of the Russian North are well known. G.P. Popov and R.A. Davydov co-authored books on the defense of the Russian North during the Crimean War, maritime navigation in the Russian North in the 19th-early 20th centuries, etc.

The Russian North — the cultural space of the Russian lands

The Russian North is not only a socio-economic, geopolitical, but also a vast cultural space of Russian lands in the European North of Russia. Culture in all its manifestations, language as its part and art reliably united the people inhabiting the ecumene space of the Russian North, no less than the power or socio-economic relations.

Candidate of Art History A.K. Chekalov (1928–1970) noted that the area of culture of the Great Russian North, the boundaries of which are commonly defined in ethnography on the basis of typical forms of housing, clothing as well as language, included not only Obonezhye and Belozerskiy Krai, Severodvinsk area (including the areas of the Sukhona Rivers , Vaga, Pinega), Mezen and Pechora lands, but also some areas to the south of the Belozersk-Vologda-Veliky Ustyug line, Cherepovets, the northern parts of the Yaroslavl and Kostroma area. The vast Northern Dvina region in the Russian North was the busiest and richest trade and craft zone with large cities and local peasant self-government. In the east, the northern types were dissolved in the cultures of the Komi and Vyatka-Perm area. The western border of the Great Russian culture, where it mixed with the Karelian-Finnish culture, was also blurred [30, p. 37].

History of culture of the Russian North of 988-1917 is deeply and comprehensively researched in the monograph by Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor G.S. Shchurov (1935–2012).

In the section “Artistic creativity”, he showed folk — artistic, literary, musical, visual, theatrical creativity, architecture. In the second section, “In order to preserve spiritual values”, the museum work, monastic and secular libraries were covered. The undoubted success of the author of this unique scientific work is the third and fourth sections on spiritual and secular education, discoverers and national healers, M.V. Lomonosov, scientific founders of fundamental trends, scientific societies and the first scientific institutions [31]. The monograph was recognized as the best book of 2004 and presented in Moscow and Paris at book exhibitions.

-

A. N. Davydov (1951-2016), a prominent specialist in the ethnography of the Russian North, the history and ethnography of Arkhangelsk, the maritime culture of the peoples of the European North, and the history of bells and bell ringing, was a member of the Scientific Council of the RAS on the History of World Culture.

Poetry of the northern ecumene: images of sea, river, forest, swamp, tundra and the motif of the path in the northern text of Russian literature, the northern text as a logos form of life of the Russian North; sociocultural space of the northern Russian village; the dynamics of the culture of the Russian North in the conditions of modern social transformations; ethnicity and culture: the problems of discourse analysis were studied in the works of professors E.Sh. Galimov, V.N. Matonina, Yu.P. Okuneva, A.N. Solovyova. With the participation of E.Sh. Galimova, a scientific project on holding All-Russian scientific conference with international participation “The Northern text of

Russian literature: the Russian North in the system of points of view” has been implemented in 2019.

Exploring the problems of archeology, ethnology, philosophy of culture and sacred geography of the peoples of the European North, Doctor of Philosophical Sciences N.M. Terebikhin revealed the features of the northern Russian traditional spatial mentality, which is important for understanding the meanings of the development of the ecumene of the Russian North. Each ethnic group has a well-known specific set of unconscious habits, stereotypes of spatial behavior and worldview, which are determined by the concept of spatial mentality. The process of mastering the macrospaces of the North, according to N.M. Terebikhin, reflected the centrifugal aspirations of the Russian soul, aimed at leaving this world and opening the Russian expanse [33, Terebikhin N.M., pp. 3–210].

Russian North and M.V. Lomonosov

A unique place in the conceptualization of the Russian North belongs to the life and writings of M.V. Lomonosov (1711-1765). M.V. Lomonosov did not use the concept “Russian North” in his works on Russian history. However, he became an iconic figure, whose unique image of a scientist is associated precisely with the Russian North. Mikhail Vasilyevich focused on the fact that peoples do not begin with names, names are given to peoples, and that the ancient Slavs and Chuds in Russia were known by the chronicles for a long time. Permia, which they call Biarmiya, stretched from the White Sea up near the Dvina River, and was a strong nation of the Chuds. They traded expensive animal skins with the Danes and other Normans; they worshipped an idol Iomala. “Chud” and the Slavs were united into one nation in some places. The Russian North was not accidentally the home of one of Russia’s greatest scholars in the 18th century. It is very important to understand exactly this interrelation and not to dwell only on when the concept “Russian North” first appeared in history.

Fig. 3. M.V. Lomonosov.

The Russian North, where M.V. Lomonosov spent his childhood and youth, had a great influence on his scientific interests, emphasized D.A. Shirina, Doctor of Historical Sciences, Profes- sor, Honored Scientist of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). M.V. Lomonosov studied the northern lights, the nature of cold and heat, the characteristics of sea ice, the possibility of conducting northern sea expeditions, the conditions for moving along the Arctic Ocean, and a number of other issues related to the development of the Arctic territories [34].

According to the Honored Worker of the Higher School of the Russian Federation, Doctor of Pedagogical Sciences, Professor T.S. Butorina (1946–2018), in the birth of the genius M.V. Lomonosov, the peculiarities of socio-economic and cultural environment of the Russian North, its unique historical and cultural wealth played a leading role in the birth of M.V. Lomonosov's genius [35, pp. 8–13]. Here he was formed as a citizen, having absorbed folk traditions, the culture of the region and spiritual values. The norms of people’s behavior, personal requirements, family values and deep respect for each other were transmitted from the older to the younger generations. The people valued qualities such as patriotism, honesty, collectivism, a humane attitude towards others, and courage.

Historian N.F. Markov (1854-1916) noted that the Russian North and Lomonosov are two concepts that are inseparable from one another. The North, hitherto motionless and almost unknown, came to life with the name of Lomonosov in his poetry and science. Although the importance of Lomonosov for the Russian North is, of course, a partial one, because the genius of this man covered the interests of the whole Russia, in all the areas of its life, nevertheless, we must admit that the Russian North is a prominent part of Lomonosov’s poetry and science [36]. Similar assessments of these and other scientists show a close vital relationship between M.V. Lomonosov with the Russian North and explain its role in understanding the concept under study.

Civilization waves of the North ecumene

The possessions of the ecumene of the Novgorod Veche Republic, the Great Moscow principality, and then Russia, were constantly growing, and not only at the expense of the territories of the Russian North. The territories of the North-East, Siberia and others were constantly annexed and settling in. The fall of Novgorod in 1478, the annexation of Pskov in 1510 and the defeat of the Ryazan principality in 1521 was the e culmination of a long struggle for the creation of a unified Russian state with its center in Moscow. Thus, historically, the civilization of the entire Russian world gradually began to shape. All historians and publicists recognize the impact of certain powerful factors (reasons, conditions) on the development of Russia, which determine the significant difference between the history of Russia and the history of other countries. Usually, there are four factors: natural-climatic, geopolitical, confessional, social organization. Westerners or “Euro-peanists” — V.G. Belinskiy, T.N. Granovskiy, A.I. Herzen, N.G. Chernyshevskiy and others believed that Russia is part of a common European civilization, and therefore the West and Russia should develop according to the same economic, social and political laws. The Westerners openly rejected the traditional Russian spiritual heritage of Orthodoxy. Slavophiles — A.S. Khomyakov, K.S. Aksakov, F.F. Samarin, I.I. Kireevskiy and their followers associated the idea of the originality of

Russian history with the special path of development of Russia and the originality of Russian culture. The fundamental idea of Russian Orthodoxy, and, consequently, the whole system of Russian life, is the idea of sobornost. Sobornost is manifested in all spheres of life Russian man: church, family, society, relations between states. Eurasianists — N.A. Berdyaev, P.A. Karsavin, I.S. Trubetskoy, G.V. Florovskiy and others, unlike the Slavophiles, insisted on the exclusivity of Russia, but not in Russian Orthodoxy, but in the Russian ethnos [37, Sokolova F.H.].

The author’s periodization of cultural, ethnic, civilizational waves in Russia, taking into account the Russian North, includes five main periods.

-

• Ancient North B.C. — Late Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Copper-Bronze and Iron Ages. Late Paleolithic — settlement and development of the northern territories by ancient people, hunting, gathering. Mesolithic Era (10th-5th millennia B.C.) — fishing, new tools and means of transport. Neolithic, Copper-Bronze and Iron Ages (5th-1st millennium B.C.) — production and use of copper, bronze, iron.

-

• Pre-Slavic period of development of the North until the 9th-10th centuries A.D. The development of the northern lands by the Finno-Ugric tribes — the Chud Zavolochskaya, the northern Komi, Ves and other Saami. Hunting, fishing, forest and sea crafts, production of iron and copper are developing.

-

• Russian North in the 9th-10th centuries — 1917 — as part of Velikiy Novgorod, the Novgorod Veche Republic, the Moscow Grand Duchy from 1478, Russia from the 16th century. The areas to the north from watershed of Volga and Onega, Volga and Northern Dvina, named later “Russian North”, were not originally part of the Old Russian state. Slavs appeared here in the 10th-11th centuries and for several centuries pushed the borders of Russia hundreds of miles to the northeast, to the White Sea and the lower reaches of the Northern Dvina, the Kola North. From the end of the 14th century, in the Russian North, after the foundation of the Mikhailo-Arkhangelsk Monastery, the Arkhangelsk North was formed. Traditional society, original culture, Orthodoxy and Old Believers. Acceleration of social stratification. Agriculture, crafts, domestic and foreign trade, shipbuilding, sawmilling and other industries are developing in the economy of the northern territories.

-

• Soviet North in 1918–1991 . Foreign intervention of the North in 1918–1920, USSR 1921– 1991. Collectivization, industrialization, cultural revolution, Gulag. The Great Patriotic War 1941–1945. Creation of a military-industrial complex in the North, three training grounds, including Nyonoksa, Novaya Zemlya, and the Plesetsk cosmodrome; pulp and paper industry, construction and other sectors of the economy. Urbanization of the region. Continued development of the Arctic, the Northern Sea Route. Crisis of the 1980s and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

-

• Russian North from 1991 to the present — a modern civilizational wave. Transition to democracy, market, post-industrial stage. Turn to traditional values, including Orthodoxy, in the conditions of confrontation with the collective West. Development of culture, infrastructure, digitalization of all spheres of social life. Functioning of the Northern Sea Transport Corridor in the changing Russian Arctic, development of seaports, roads. Implementation of national projects for the socio-economic development of the Russian Federation. Special military operation in Ukraine, liberation of Donbass. The new quality of modern Russia since 2022.

The five main civilizational waves of Russia include not only archeology, ethno-cultural history, but also the economy, statehood. The essence of conceptual approach here is that statehood, culture in its broadest sense, the evolution of ethnic groups, their movement, religion, traditional and modern forms of management, economy, politics, and society are the basis for the proposed classifications. The history of the Russian North as a geocultural, civilizational space is practically inseparable from the Russian national history during the seven stages of statehood in the 9th–21st centuries I have identified:

-

• Velikiy Novgorod (862–1136) and Novgorod Veche Republic (1136–1478) from the Baltic Sea to the Ural Mountains, from the White Sea to the upper reaches of the Volga and the Western Dvina (Novgorodskaya land). Pskov and Vyatka Veche republics.

-

• Kievskaya Rus (882–1240). The Rurik dynasty, originating in Velikiy Novgorod.

-

• Moscow principality (1263–1478).

-

• Russian State, Russia (1478–1721).

-

• Russian Empire (1721–1917). February Revolution.

-

• Soviet period. October Revolution. Civil war, foreign intervention in the North. USSR in 1922–1991, Great Victory in the Patriotic War 1941–1945. The collapse of the Union State in 1991.

-

• The Russian Federation: a time of hope and disappointment, 1991 to the present. 2022 — the start of change.

Conclusion

Man has lived and continues to live in the North in harsh natural conditions. The Russian North is special, mysterious, beautiful, rich, immense and dangerous; it attracts people and unites them, because one will not master it alone and will not conquer it, no matter how strong and even impudent a person is. Simon, Metropolitan of Murmansk and Monchegorsk, said the most important words for understanding the meaning of the habitation of the ecumene. “And on the new wave of development of the Russian, namely the Russian, North, we must not forget that the main thing is the spiritual component, cultural values, social environment” 6.

The ethnic picture of the settlement of the northern ecumene does not remain unchanged in time and space. Even before the arrival of Slovenes, Ladoga, Novgorodians in the 10th-12th centuries, people lived in the North for many centuries — an autochthonous, indigenous population. Forests and the sea, rivers and lakes ensured the development of the northern Finno-Ugric civilization. The main occupations were agriculture and hunting, fishing, forestry and sea crafts, handicrafts. Chud, Merya, Karelian, Murom occupied the entire north of the East European Plain in the first millennium of our era. The example of the Chud question shows that the Russian North has always been characterized by linguistic and cultural diversity. The predominant ethnic element in the Novgorod and Upper Volga colonization was the Russian population, although other ethnic groups also took a significant part in this movement.

Periodization and determining the historical and archaeological areas of the Russian North in the 21st century are largely conditional and justified by the fact that the Republics of Karelia and Komi, Arkhangelsk, Vologda, Murmansk, Novgorod, Pskov, Leningrad oblasts have their own administrative bodies, their own scientific schools and centers, including regional sources of funding.

In the civilizational paradigm, the multicultural Orthodox civilization, like the Russian world, has had its own complicated history for twelve centuries, including all of the aforementioned stages of statehood, forming its own identity. Russia in its significance is a key part of the Russian world today. The modern world is changing radically. In fact, there is a process of demarcation of the global geopolitical space into several poles of economic, military-political power, socio-cultural diversity — the Euro-Atlantic, Eurasian, Asia-Pacific, Russian world, etc.

Список литературы A Word about the "Russian North" Concept

- Yanin V.L. Ocherki istorii srednevekovogo Novgoroda [Essays on the History of Medieval Novgorod]. Moscow, Yazyki slavyan, kul’tura Publ., 2008, 400 p. (In Russ.)

- Edovin A.G. Stanovlenie arkheologicheskoy nauki v Arkhangel'skoy gubernii (1868 1941) [The For-mation of Archaeological Science in the Arkhangelsk Province (1868 1941)]. In: Sbornik materialov Vserossiyskoy nauchno prakticheskoy konferentsii s mezhdunarodnym uchastiem “Arkheologiya v muzeynykh kollektsiyakh” [Collection of Materials of the All Russian Scientific and Practical Confer-ence with International Participation "Archaeology in Museum Collections"]. Arkhangelsk, Lotsiya, 2019, 232 p. (In Russ.)

- Gurova N.N. Drevnyaya istoriya Severo Zapada Evropeyskoy chasti SSSR [Ancient History of the North West of the European Part of the USSR]. Moscow, Leningrad, Akademiya nauk SSSR Publ., 1961, 588 p. (In Russ.)

- Formozov A.A. Ocherki po istorii russkoy arkheologii [Essays on the History of Russian Archeology]. Moscow, Akademiya nauk SSSR Publ., 1961, 128 p. (In Russ.)

- Makarov N.A. Arkheologicheskie dannye o kharaktere kolonizatsii Russkogo Severa v X XIII vv. [Ar-chaeological Data on the Nature of the Colonization of the Russian North in the X XIII Centuries]. Sovetskaya arkheologiya [Soviet Archeology], 1986, no. 3, pp. 61 71.

- Kuznetsova V.P. Tselezero: zabyt' nel'zya, vernut'sya nevozmozhno…: dokumenty, vospominaniya [Celezero: Impossible to Forget, Impossible to Return...: Documents, Memoirs]. Arkhangelsk, Lotsi-ya, 2021, 255 p. (In Russ.)

- Yasinski M.E., Ovsyannikov O.V. Vzglyad na Evropeyskuyu Arktiku: Arkhangel'skiy Sever: problemy i istochniki. V 2 kh tomakh [A Look at the European Arctic: Arkhangelsk North: Problems and Sources. In 2 Vol.]. Saint Petersburg, Peterburgskoe vostokovedenie Publ., 1998, vol. 1, 464 p.; vol. 2, 332 p. (In Russ.)

- Ryabinin E.A. Finno ugorskie plemena v sostave Drevney Rusi: k istorii slavyano finskikh etnokul'turnykh svyazey: Istoriko arkheologicheskie ocherki [Finno Ugric Tribes as Part of Ancient Russia: On the History of Slavic Finnish Ethno Cultural Relations: Historical and Archaeological Es-says]. Saint Petersburg, Izdatel'stvo Sankt Peterburgskogo universiteta Publ., 1997, 200 p. (In Russ.)

- Kalutskov V.N. Obrazno geograficheskaya karta Russkogo Severa [Image Geographical Map of the Russian North]. In: Russkiy Sever 2018: Problemy izucheniya i sokhraneniya istoriko kul'turnogo naslediya: Sbornik materialov II Vserossiyskoy nauchnoy konferentsii s mezhdunarodnym uchastiem (Tot'ma, 1 4 marta 2018 g.) [Russian North 2018: Problems of Studying and Preserving the Histor-ical and Cultural Heritage: Collection of Materials of the II All Russian Scientific Conference with In-ternational Participation (Totma, March 1 4, 2018)]. Vologda, Poligraf Periodika Publ., 2018, pp. 210 215. (In Russ.)

- Tolstov S.P., Aleksandrov V.A., Guslistyy K.G., Zalesskiy A.I., Sokolova V.K., Chistov K.V., eds. Etnograficheskie ocherki [Ethnographic Essays]. Moscow, Nauka Publ., 1964, 494 p. (In Russ.)

- Putilov B.N., Chistov K.V., eds. Fol'klor i etnografiya Russkogo Severa: sbornik statey [Folklore and Ethnography of the Russian North: Collection of Articles]. Leningrad, Nauka. Leningradskoe otdele-nie Publ., 1973, 280 p. (In Russ.)

- Bernshtam T.A., ed. Russkiy Sever: Aspekty unikal'nogo v etnokul'turnoy istorii i narodnoy traditsii [Russian North: Aspects of the Unique in Ethno Cultural History and Folk Tradition]. Saint Peters-burg, 2004, 415 p. (In Russ.)

- Drannikova N.V. Lokal'no gruppovye prozvishcha v traditsionnoy kul'ture Russkogo Severa: Funktsional'nost', zhanrovaya sistema, etnopoetika [Local Group Nicknames in the Traditional Cul-ture of the Russian North: Functionality, Genre System, Ethnopoetics]. Arkhangelsk, Pomorskiy gosudarstvennyy universitet Publ., 2004, 432 p. (In Russ.)

- Toporov V.N. Predystoriya literatury u slavyan: Opyt rekonstruktsii (Vvedenie k kursu istorii slavyan-skikh literatur) [Prehistory of Literature among the Slavs: Experience of Reconstruction (Introduction to the Course in the History of Slavic Literature)]. Moscow, RGGU Publ., 1998, 320 p. (In Russ.)

- Azbelev S.N. Gostomysl. In: Varyago russkiy vopros v istoriografii [Varyago Russian Question in His-toriography]. Moscow, Russkaya panorama Publ., 2010, pp. 381 392. (In Russ.)

- Raevskiy D.S., Petrukhin V.Ya. Ocherki istorii narodov Rossii v drevnosti i rannem srednevekov'e [Es-says on the History of the Peoples of Russia in Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages]. Moscow, Znak Publ., 2004, 416 p. (In Russ.)

- Vasilyev A.A. O drevneyshey istorii severnykh slavyan do vremen Ryurika, i otkuda prishel Ryurik i ego varyagi [About the Ancient History of the Northern Slavs before the Time of Rurik, And Where Rurik and His Vikings Came From]. Saint Petersburg, Tipografiya Glavnogo shtaba E.I.V. po voenno uchebnym zavedeniyam Publ., 1858, 169 p. (In Russ.)

- Stringholm A.M. Pokhody vikingov [Viking Expeditions]. Moscow, AST Publ., 2003, 736 p.

- Oroziy P. Istoriya protiv yazychnikov. Knigi I VII [History against the Pagans. Books I VII]. Saint Pe-tersburg, Oleg Abyshko Publishing House, 2004, 541 p. (In Russ.)

- Sedov V.V. Vostochnye slavyane v VI XIII vv [Eastern Slavs in the VI XIII Centuries]. Moscow, Nauka Publ., 1982, 327 p. (In Russ.)

- Nasonov A.N. “Russkaya zemlya” i obrazovanie territorii Drevnerusskogo gosudarstva: Istoriko geograficheskoe issledovanie. Mongoly i Rus': Istoriya tatarskoy politiki na Rusi [“Russian Land” and the Formation of the Territory of the Old Russian State: Historical and Geographical Research. Mon-gols and Rus: A History of Tatar Policy in Rus]. Saint Petersburg, Nauka Publ., 2006, 364 p. (In Russ.)

- Fletcher J. O gosudarstve russkom [About the Russian State]. Moscow, Zakharov Publ., 2002, 169 p. (In Russ.)

- Likhachev D.S. Novgorod Velikiy: ocherk istorii kul'tury Novgoroda XI XVII vv [Novgorod the Great: An Essay on the History of the Culture of Novgorod in the 11th 17th Centuries]. Moscow, Sovetska-ya Rossiya Publ., 1959, 102 p. Reissue: Leningrad, Gospolitizdat Publ., 1945, 103 p. (In Russ.)

- Zharnikova S.V. Arkhaicheskie korni traditsionnoy kul'tury russkogo Severa: sbornik nauchnykh statey [Archaic Roots of the Traditional Culture of the Russian North: Collection of Scientific Articles]. Vo-logda, MDK Publ., 2003, 97 p. (In Russ.)

- Engelhard A.P. Russkiy Sever: putevye zametki [Russian North: Travel Notes]. Saint Petersburg, A.S. Suvorin Publishing House, 1897, 262 p. (In Russ.)

- Zhuravskiy A.V. Evropeyskiy Russkiy Sever. K voprosu o gryadushchem i proshlom ego byta [European Russian North. To the Question of the Future and the Past of Its Life]. Arkhangelsk, Gubernskaya ti-pografiya Publ., 1911, 36 p. (In Russ.)

- Kizevetter A.A. Russkiy Sever. Rol' Severnogo Kraya Evropeyskoy Rossii v istorii russkogo gosudarstva [Russian North. The Role of the Northern Territory of European Russia in the History of the Russian State]. Vologda, Tipografiya Soyuza severnykh kooperativnykh soyuzov Publ., 1919, 66 p. (In Russ.)

- Vlasova I.V. Russkiy Sever: istoriko kul'turnoe razvitie i identichnost' naseleniya [Russian North: His-torical and Cultural Development and Identity of the Population]. Moscow, IEA RAN Publ., 2015, 376 p. (In Russ.)

- Bulatov V.N. Russkiy Sever [Russian North]. Moscow, Gaudeamus: Akademicheskiy proekt Publ., 2006, 570 p. (In Russ.)

- Chekalov A.K. Narodnaya derevyannaya skul'ptura Russkogo Severa [Folk Wooden Sculpture of the Russian North]. Moscow, Iskusstvo Publ., 1974, 191 p. (In Russ.)

- Shchurov G.S. Ocherki istorii kul'tury Russkogo Severa, 988 1917 [Essays on the History of Culture of the Russian North, 988 1917]. Arkhangelsk, Pravda Severa Publ., 2004, 551 p. (In Russ.)

- Permilovskaya A.B. Russkiy Sever spetsificheskiy kod kul'turnoy pamyati [The Russian North is a Specific Code of Cultural Memory]. Kul'tura i iskusstvo [Culture and Art], 2016, no. 2 (32), pp. 155 163. DOI: 10.7256/2222 1956.2016.2.18345

- Terebikhin N.M. Metafizika Severa [Metaphysics of the North]. Arkhangelsk, Pomorskiy universitet Publ., 2004, 272 p. (In Russ.)

- Shirina D.A. Arktika i Sever v trudakh M.V. Lomonosova [The Arctic and the North in the Works of M.V. Lomonosov]. Nauka i tekhnika v Yakutii [Science and Technology in Yakutia], 2011, no. 2 (21), pp. 3 7.

- Butorina T.S. Lomonosov i Sever [Lomonosov and the North]. In: Lomonosov i Sever: bibliografich-eskiy ukazatel' [Lomonosov and the North: bibliographic index]. Arkhangelsk, Arkhangel'skaya ob-lastnaya nauchnaya biblioteka imeni N.A. Dobrolyubova Publ., 2011, pp. 8 13. (In Russ.)

- Markov N.F. Russkiy sever v proizvedeniyakh M.V. Lomonosova: Rech', chitannaya v torzhest vennom sobranii “Vologodskogo obshchestva izucheniya Severnogo kraya” v den' chestvovaniya 200 letiya pamyati Lomonosova 8 noyabrya. 1911 g. [The Russian North in the Works of M.V. Lomonosov: Speech Read at the Solemn Meeting of the "Vologda Society for the Study of the Northern Territory" on the Day of Honoring the 200th Anniversary of Lomonosov's Memory on November 8, 1911]. Vo-logda, 1912, 17 p. (In Russ.)

- Sokolova F.Kh. Istoriya Rossii: uchebno metodicheskoe posobie [History of Russia: Teaching Guide]. Arkhangelsk, Kira Publ., 2013, 126 p. (In Russ.)