About Russian Alaska and Its Ruler A.A. Baranov

Автор: Lukin Yu.F.

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Reviews and reports

Статья в выпуске: 45, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The purpose of this study is to analyze the present and past of the history of Alaska. Such a combination of times highlighted the most difficult problem of ambiguous attitude to the historical past in the USA from the standpoint of modernity. In the process of destroying monuments under the onslaught of the Black Lives Matter movement, the local Indian population accused the long-gone A.A. Baranov of racism, persecution of the indigenous population, enslavement of Tlingits and Aleuts for hunting fur-bearing animals. On July 14, 2020, the Sitka town and district assembly supported these accusations and decided to move his monument from the town square to the local museum. The review article reveals the objective conditions of the historical process during the period of A.A. Baranov's activity in Alaska in 1790–1818, using the methods of historicism, search and systematization of information, analysis and synthesis. The assessment of his personality is updated. The article shows the beginning of G.I. Shelikhov's and A.A. Baranov's activity in the North-Eastern Company, and then its transformation in 1799 into the Russian-American Company (RAC). The article examines the war with the Tlingit people of 1802–1804, the missionary work of Herman Alaskinskiy, three assessments of the nature of Russian colonization, N.P. Rezanov's plan for the modernization of RAC. The episode with Russia's sale of Alaska to the United States is also being clarified.

Alaska, G.I. Shelikhov, A.A. Baranov, German Alaskinskiy, N.P. Rezanov, Russian-American Company (RAC), Tlingits, monument, Sitka

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148323183

IDR: 148323183 | УДК: [325.3+327.8 + 338.22](739.8)(09)(045) | DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2021.45.229

Текст научной статьи About Russian Alaska and Its Ruler A.A. Baranov

On the relocation of A.A. Baranov’s monument in the city of Sitka in 2020

Monument to A.A. Baranov was erected in downtown Sitka, Alaska on October 25, 1989. A statue of sculptor Joan Bugby-Jackson was donated to the municipality by the Hames family and installed in the park in front of the Harrigan Centennial Hall community center on the ocean.

Fig. 1. Ambassador A.I. Antonov and R. Hames, June 2019.

The inscription on the pedestal of the monument is “So that we may always remain in friendship and peace in this region”. Unfortunately, in the summer of 2020, a group of local activists opposed the

∗ For citation: Lukin Yu.F. About Russian Alaska and Its Ruler A.A. Baranov. Arktika i Sever [Arctic and North], 2021, no.

-

1 URL: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EG9-tAzWwAAPfks.jpg (accessed 20 July 2021).

historical past and started pushing for the monument to be removed from the city centre. The Municipal Administrator's Office held to its stated value: “We respect and support the changing needs of our customers, their elected representatives and our employees. We appreciate their ability and contribution to making Sitka the benchmark—in every way—by which all other cities are measured” 2. City manager John Leach remarked at the time: “The performances of this group, in a sense, are on a par with everything else that is happening in the USA right now” 3. Relations between people, values and historical events are increasingly subjected to critical scrutiny in the modern world. Alaska in the USA is no exception.

The demand of local activists in Sitka took place against the background of the activist movement “Black Lives Matter” (BLM) in 2020. This socio-political protest movement against police brutality and racial violence, advocating various political changes related to the liberation of blacks, functioned in 2013–2020. The movement received further international attention during global protests following the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, who was sentenced to 22.5 years in prison 4. Black Lives Matter is a decentralized network of activists without a formal hierarchy, includes many different opinions and a wide range of requirements, a heterogeneous composition. It concerns not only the provision of basic human rights for all black people under “white supremacy”, but also the alleged general injustice of the American system, the ideology of oppression (identity politics). A June 2020 Pew Research Center poll found that 67% of American adults expressed some support for the Black Lives Matter movement. In September 2020, support for this movement among American adults dropped to 55%. It is mainly supported by the black population, a noticeable decrease was observed among whites and Hispanics 5.

In the city of Sitka, Alaska, on June 23, 2020, about 90 people gathered around the statue of Baranov, asking the city authorities to move the monument to a less conspicuous place, since it might offend the feelings of the Tlingits.

Fig. 2. President of the Alaska Native Sisterhood Paulette Morin is speaking.

Dion Brady-Howard is drumming and singing 6.

At the Sitka Assembly meeting, Doug Osborne presented a petition with about 900 signatures. Over the years, people have called for the removal of the statue, which has been damaged several times. “This monument is not about telling our story, not about recognizing it. This is a monument, this is a place of honor for someone who does not deserve our honor,” said Dion Brady-Howard, whose Tlingit name is Eidikuaa. During the meeting, Nikolai Galanin stated: “Baranov is a historical figure responsible for murders, enslavement, rape and genocide. This history is still being felt by our indigenous communities. The number of indigenous women is statistically higher than all the missing and killed throughout North America. Our languages must be revived because they were forcibly taken from us” 7.

However, analyzing all the performances, it is necessary to emphasize one important feature. The motivation of the protesters was not only and not so much in the events of the past, but, on the contrary, in the reaction to the events of the present, an attitude towards the realities of the US in 2020. It was said that women from the indigenous population are statistically significantly more likely to go missing and become victims of murder throughout North America here and now. Assembly member Valorie Nelson, in turn, said that she considers the discussion around the statue of Baranov controversial. She told about her unpleasant incident in the past and declared her fatigue from all this 8.

When it became known that some local residents were in favour of the demolition of this monument, the CCORC — the Coordinating Council of Organizations of Russian Compatriots in the United States — launched an online petition to the Sitka authorities to keep all the monuments in their current locations and installations. The history of Alaska in the past was “sixteen shades of gray”: wars, peace, mutual trade, cultural exchange, intertribal and interethnic marriages. Approximately 6 thousand people have signed the US CCORC petition. In contrast, the petition of the supporters of moving the statue got less than 3 thousand votes 9. The keynote of supporters of preservation of the monument to A.A. Baranov was the following: “It is a big mistake to judge the history and historical monuments by the modern standards. If we follow the slippery slope of distorting history to suit the desires of particular racial, ethnic or identity groups, we will only exacerbate existing ethnic, racial and cultural conflicts” 10.

On July 14, 2020, at a meeting of the city Sitka and District Assembly, a decision was discussed to transfer the monument to A.A. Baranov to the Museum of the Sitka Historical Society. Another alternative proposal was to include the question of removing the monument to Baranov from its current location on the ballot of the next municipal elections on October 6, 2020 11. However, this proposal did not find support. The adopted resolution of the Sitka Assembly dated July 14, 2020 listed a number of accusations against A.A. Baranov. It was said that “The Baranov Monument continues to normalize a figure saturated with racial division, violence and injustice. Sitka has a choice about the values it can project” 12. According to the decree, A.A. Baranov led enslavement of the Tlingit and Aleuts for hunting fur-bearing animals until they completely disappeared; abuse of local women, families and the law; murders and theft of local property — often justified by theories of racial and cultural superiority. The locals nicknamed him “no heart”. “His violent legacy continues to ripple through time, waves of historical trauma still hurting indigenous people to this very day,” the Sitka City and District Assembly noted 13.

It is quite clear that the Sitka City and District Assembly resolution was adopted in 2020 in the mass wave of the toppling of statues of Confederates and colonialists in the USA, caused by mass protests against racism in the USA.

It is important to note that previously, in the recent past, the situation was still different. For example, in March 2017, the nature of the protests on the 150th anniversary of the sale of Alaska was more objective. Chief of the Tlingit Tribe, 12th Lieutenant Governor of Alaska 2014– 2018 Byron Mallott (1943–2020), stated at the time that “We are looking at 150 years with very wide open eyes. Both under Russian and American rule there have been pro-problems for Alaska Native peoples”. Sergei A. Kan, a professor at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, who has studied the ethnology and ethnohistory of Native Americans, including the Tlingit, said that when the Russians arrived in Alaska, they used coastal people to hunt sea otters. After the sale of the land, the indigenous groups were freed, but the Americans brought new problems. “The Russian era was associated with paternalistic control, but the task of Russia was not a radical transformation of life, but the use of people for economic purposes. With the Americans, this was accompanied by a much stronger Westernization”. Bob Sam, a Tlingit born and raised in Sitka, remarked in 2017 that not everyone was happy about the 150th anniversary: “It's time to heal and find unity so Alaska Natives can continue to be the people they were meant to be” 14.

The Sitka History Museum, also known as the Sitka Historical Society and Museum, proudly displays the entire history of the Tlingit indigenous people and the period of Russian colonization from Tlingit totem poles to artefacts of the Russian Orthodox Church. St. Michael's Cathedral, the Baranovskiy Castle State Historical Monument are among the 9 amazing places to visit in Sitka. The restored “Russian Bishops’ House” speaks of Russia's little-known colonial heritage in North America 15. The Sitka National Historical Park preserves the scene of a battle between “invading Russian traders and the native Kiksadi”.

In relation to the monument's 2020 relocation, Hal Spackman, director of the history museum, said: “The museum's placement facilitates a respectful compromise in a difficult, somewhat controversial discussion” 16. He explained that the museum already has a space that talks about Alexander Baranov, his life in Sitka, the Russian-American Company and its influence, and the conflicts the Russians had with the Tlingit at the time. According to the director, the Tlingit perspective on these conflicts and their resolution is also presented. He also admitted that the monument to A. Baranov could someday be brought to Russia as part of the exchange of exhibitions between museums. Sale is excluded, exchange is possible 17. In the summer 2020, there were offers from Arkhangelsk, Irkutsk, Magadan, St. Petersburg, to buy out the statue of A.A. Baranov and transport it to Russia.

Brief review of literature sources about A.A. Baranov

In order to understand the mission and significance of A.A. Baranov in the development of Russian America, it is necessary to return to the end 18th – beginning of the 19th centuries. Alaska and part of California in 1741–1867 were positioned as Russian America. The history of its development is inextricably linked with the activities of the Russian-American Company (abbreviated as RAC), named after A.A. Baranov, who was born in Kargopol, Olonets Gubernia, and was engaged in commercial and industrial activities in the North, in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Siberia, and then in Alaska.

One of the well-known domestic researchers of the history of Alaska, S.N. Markov (1906– 1979), obtained access to some documents, which were previously considered hopelessly lost. Private archives of Grigory Ivanovich Shelikhov (1747–1795) and his son-in-law Mikhail Matveyevich Buldakov (1766–1830), the leading director of the Russian-American Company in 1799–1827, were not preserved as a whole. We are talking about a part of the archive of M.M. Buldakov, a native of Velikiy Ustyug, discovered in 1923 [1, p. 46]. In Russia, the materials of the RAC are stored in the Russian State Archive of Foreign Affairs (f. 1605) and Russian State Historical Archives. There are two fonds “Siberian Affairs” and “Russian-American Company” in the Archive of Foreign Policy of Russia. The US Library of Congress has a collection of the Russian merchant and famous collector G.V. Yudin (1840–1912), including documents from the RAC, as well as the archives of Novoar-khangelsk, Ross, Kodiak, Unalashka, and the Pribyloviy Islands 18.

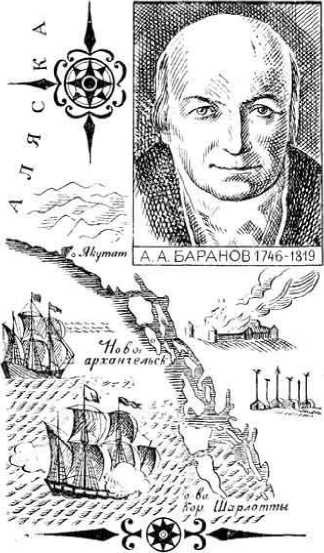

Fig. 3. Baranov A.A. From the book of S.N. Markov “History of Alaska”, p. 14.

American historian F.A. Golder (1877–1929), Doctor of Philosophy and author of the book “Russian Expansion on the Pacific, 1641–1850”, referred to the history of Alaska as part of American history during the period of Russian expansion [2, p. 13]. A brief historical overview of the discovery and colonization of the North-West of America by Russia (1741–1867) was given in the book of the American professor V.P. Petrov “Russians in the history of America” 19.

It is worth to mention the fundamental project by the team of authors “History of Russian America” (1732–1867) in three volumes, ed. by RAS Academician N.N. Bolkhovitinov (1930–2008) [3, 1511 p.]. The Russian scientist N.N. Zubov (1885–1960) in his work “Domestic Sailors — Explorers of the Seas and Oceans”, devoting two chapters to the activities of G.I. Shelikhov (1775–1795) and A.A. Baranov in Russian America (1790–1818) [4, pp. 124–127, 132, 206–211]. Review of sources and literature, history of the Tlingit Indians, their relations with the Europeans during Russian America 1741–1867 are described in the works of Professor A.V. Grinev, Chairman of the Russian Association of American Anthropologists [5].

The problems of Russian Alaska are periodically discussed at scientific conferences. In the materials of the 14th Kargopol Scientific Conference (August 15–16, 2016), the third section “Russian North and Russian America” has 11 articles about A.A. Baranov, his family tree, Russian America [6, pp. 318–384]. Bibliographic indexes of available literature, sources about “Russian America”, published in 2012 in Vologda 20 and in Moscow in 2013 [7], include documents, letters, maps, reference books, monographs, collections, teaching aids, articles, abstracts, electronic and other resources.

Life and destiny of A.A. Baranov, RAC activities in North America are reflected in journal articles, media, Wikipedia 21. Media sometimes report minor inaccuracies: instead of the Olonets province as the birthplace of A.A. Baranov, the Astrakhan Oblast or Arkhangelsk Gubernia are indicated 22. In general, there is a permanent public and scientific interest both to A. A. Baranov personality and Alaska history. Historiography, the source base of the research question, of course, is not limited to these works. In this article the author studies only a small part of available materials on the history of Russian America and the fate of our countryman A.A. Baranov.

A.A. Baranov's beginnings in North America

Expansion (extension, growth) is a characteristic of any empire, a necessary condition for its stability, regardless of the real need for new territories. Spanish expansion to America began in the 15th century (Columbus, 1492), British one — in the 16th century 23. However, by the middle of the 18th century, neither Britain nor Spain owned any possessions, nor had any information about the northwestern half of North America, called Russian America. Major geographical discoveries of the 18th century in North America were made by Russian sailors [4, Zubov N.N.]. “Only thanks to the exploits of Russian explorers of the 17th century (most of whom, by the way, came from the basins of the Northern Dvina and Onega), Bering's voyages of the 18th century and further expansion to America of the Russian Empire, followed by the expansion of Britain and Spain, and then the USA became possible” [6, Shmakin V.B., p. 324].

Fig. 3. Grigoriy Shelikhov 24.

Entrepreneur G.I. Shelikhov (1749–1795) together with the merchant I.I. Golikov (1735– 1805) founded the North-Eastern Company in 1781. Its mission was to explore and develop new lands and industries on the North American continent, expanding the possessions of the Russian Empire. The expedition of G.I. Shelikhov in 1783 set off from Okhotsk to the shores of North America and arrived in the summer of 1784 on Kodiak Island, where he lived for about two years [3, pp. 73–84]. In 1787, G. Shelikhov returned to Russia. Together with their companion, I. Golikov, they reported to Catherine II the results of their research and work, as well as their project of a monopoly private company for the further development of Russian America, but were refused [3, p. 87]. G.I. Shelikhov understood that real development, raising the culture and wealth of the Aleutian Islands, nearby regions of North America, is possible only on the basis of permanent Russian settlements and establishing relations with local residents there [3, p. 82]. The main reason that drew many Russian industrialists on difficult and dangerous voyages to the Commander and Aleutian Islands was the hope for rapid enrichment [4, p. 219].

On August 15, 1790, in the port city of Okhotsk, a successful fur trader, founder and owner of the North-East Company “Grigorey Ivanov, son Shelikhov, a noble citizen of Ryol, and Alexander Andreyev, son Baranov, a merchant of Kargopol, a guest from Irkutsk” signed an agreement. It clearly stipulated the division of shares into 210 parts, depending on fishing, exchange, purchase of goods, “in soft loot or other goods”. There should be 192 people in the company, excluding seamen and others. Baranov was obliged to follow the instructions only from the governments and his companion Shelikhov, “I am not obliged to follow anyone else's instructions and have nothing to do with me”. In general, A.A. Baranov, as the main ruler in America, “as the head of the American coast and settlements, at the disposal and management of the North-Eastern Company” received large powers to manage and organize all the life in the American land and islands 25.

After the mysterious death of Grigoriy Shelikhov on July 20, 1795, his cousin Ivan Shelikhov and widow Natalia Shelikhova managed the affairs of the North-Eastern Company. G.I. Shelikhov made an extremely important step in strengthening the family, having married his eldest daughter Anna in January 1795 to N.P. Rezanov, who launched an active support to the Shelikhovs in the late 1790s. In 1797, M.M. Buldakov became the husband of Avdotya Shelikhova. He was one of the richest and most famous fur dealers, who later played a prominent role in the affairs of the Russian-American Company [3, p. 98].

A.A. Baranov founded the Archangel Michael redoubt at the mouth of Starrigavan Bay in 1799. After the war with the Tlingit in 1802–1804, the settlement was moved to a strategically more convenient place, was named Novo-Arkhangelsk and became the main city of Russian America since 1808, from 1867 — Sitka. According to the English sailor Peter Korney, who visited these places in the 1810s, Novo-Arkhangelsk consisted of a fort on a mountain and a settlement of 60 wooden houses, as well as a church, a blockhouse, and a shipyard. Each house had a vegetable garden with potatoes, carrots, radishes, turnips and other vegetables 26.

Fig. 4. Novo-Arkhangelsk. Drawing by I.G. Voznesenskiy (1839–1849).

The North-Eastern Company was transformed into the Russian-American Company (RAC) by decree of Emperor Paul I of July 8 (19), 1799. According to A.S. Grinev, the combination of the interests of national entrepreneurs and the tsarist bureaucracy resulted in their symbiosis in the form of the RAC. Although formally the company was a private organization, in reality it was a kind of branch of the state apparatus and existed under strict government control. The “nationalization” of the RAC was also manifested in the ease of receiving government loans for hundreds of thousands of rubles by this seemingly private company received. In 1802, for example, the treasury gave the company 200 thousand rubles, in 1803 —150 thousand rubles more [3, Bolkhovitinov

N.N., vol.2, pp. 230–231]. It is also very symbolic that the RAC was granted a special flag in 1806, repeating the colors of the national one, with a double-headed royal eagle 27. The special status of the RAC is also shown by the company's numerous privileges and the possibility to inform the Emperor about its problems directly. The RAC of the 19th century can be compared in this sense with PJSC Gazprom or Rosneft in modern Russia of the 21st century.

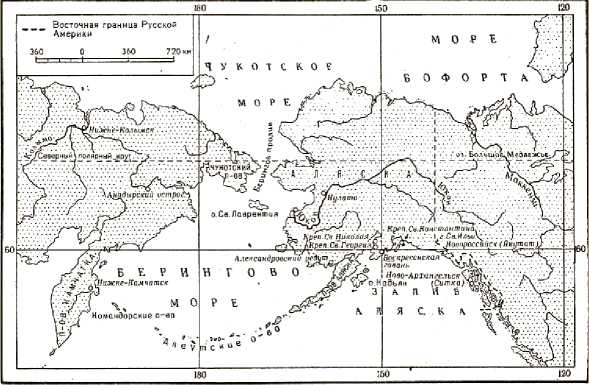

Fig. 5. Possessions of the RAC in North America under the agreements of 1824 and 1825 28.

The sea fur trade constantly motivated the Russians to move further and further along the coast of the New World, looking for new places for their economic activities. The advance of the Russians went along the coast to the west and south, including Alaska, the Aleutian Islands, settlements in California, the Hawaiian, Kuril and Commander Islands. Russian settlements in North America often experienced an acute need for bread and salt, weapons and gunpowder, as trades were impossible without it. The supply of food and goods to the settlements of the Russian-American Company, the delivery of tools and equipment for the ships being built in Okhotsk and in Russian America, were extremely difficult. Everything needed was carried on carts through Siberia; thousands of horses were required, the journey lasted about a year, and sometimes more [4, Zubov N.N.]. Developing trade with entrepreneurs from the USA, A.A. Baranov managed to establish a food supply, but the problem of the lack of bread was still not resolved.

The history of Russian America development is difficult to understand without analyzing the relationship between Russians and the indigenous population. Although Russia's possessions in the New World bore the proud name of “Russian America”, the Russians themselves were always a minority, even in their own colonies. The first group of the local population consisted of the Aleuts and Eskimos of South Alaska (Kodiaks, Alaskans and Chugachs), as well as the Tanaina Indians, dependent on the company and living under the control of Russian military-trading and administrative-economic settlements or directly in them. The second group included the Eskimos Aglegmuts and various Indian tribes: Atna, Eyaks (Ugalakhmuts or Ugalentsy) and Tlingits, not dependent on the RAC. The company traded with those who lived on the border of Russian-controlled territory, took amanata as hostages for the security of its workers, and hired them as volunteers for work at the earliest opportunity. At the very bottom of the social ladder were the so-called “kayurs” or “servants of the Aleuts” (regardless of ethnic origin), the most powerless part of the population [3, Bolkhovitinov N.N., vol. 2, pp. 236–237].

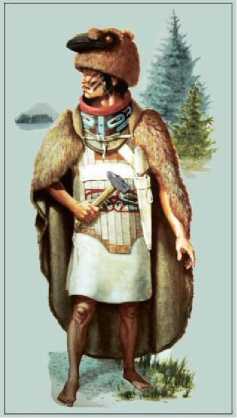

In the life of the Alaska and Aleutian aborigines there have always been tribal wars and blood feuds, mutual trade and cultural exchange. The Indians called themselves “Tlinkit” (Tlingit, Lingit, Klinkit), meaning “person, people”. In Russian sources, the Tlingit, as a rule, were denoted by the word “koloshi” with the stressing on the first syllable [5, pp. 21–22]. The economy of the Tlingits was based on fishing, an emerging craft. Men made tools, utensils, boats, weapons; women weaved capes, baskets, mats and hats, sewed clothes. Exchange of goods and material culture developed. Military confrontations and frequent wars played an important role in Tlingit life. In full armor, the Tlingit warrior resembled a medieval European knight [5, pp. 31–42, 66–67].

Tlingit religious ideology was a complex of totemism, animalism, fetishism, magic, animism, and shamanism. A special place in this complex was occupied by totemism — a belief in a supernatural link that seems to exist between a group of people and a certain kind of animal, an object or a model [5, pp. 73–74]. A brochure of the Sitka Historical Museum (2018) noted several types of totem poles — monumental sculptures carved from huge trees. One of them depicted a supernatural Beaver, who, according to the legend, killed the leader of the clan with the help of a miraculous bow and destroyed the village with a blow of his tail. The tomb totem pole of the Chukanedi family contains the ashes of Dahuket, one of the Indian leaders 29.

War with the Tlingit, 1802–1804

The causes of the war with the Tlingits were, according to A.V. Grinev, first of all, a clash of economic interests between the Indians and the RAC, which launched an intensive fishery. This encouraged the Tlingit to protect their fishing grounds. The dissatisfaction of the Indians was caused by the dismissive attitude of some Russian industrialists towards them. Aleut port men plundered Indian burial grounds. The Tlingit themselves would not mind plundering the Mikhailovskaya fortress. Another reason was considered to be the instigation of the English-American sea merchants — RAC competitors [5, pp. 118–120]. Forming the hostility of the Tlingit to the Russians, the English-American competitors of the RAC pursued, first of all, their economic interests. The strengthening of the Russian presence threatened them with a decrease in profits.

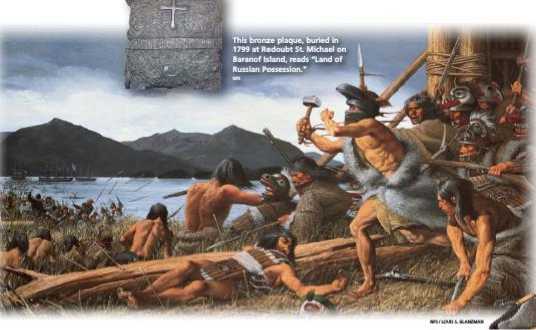

In 1802–1804, there was an armed conflict between the Tlingit and Russian fur hunters, their Aleut allies, known as the “Battle of Sitka”. The reason was the RAC’s desire to create its outpost in the southeast of Alaska. Under the leadership of A.A. Baranov, the manager of the company, a group of Russians and Alaska Natives built the St. Michael redoubt near Starrigavan Bay in 1799. The powerful leaders of the Kix.adi Indian clan began to resent this Russian invasion. The Sitka National Historical Park comments on the location of this battle with the phrase “Who Will Control These Lands?”, explaining everything by Russian expansion 30.

Fig. 6. Catlian. Modern reconstruction. From the Sitka National Historical Park collection.

In 1802, the Tlingits, in helmets and with animal-headed armor, headed by their leader Kat-lian, attacked the settlement of Starrigavan. Most of the Russians and the Aleuts who defended it were killed. Terrible armor and invulnerability to rifle fire then made an impression on the Russians. A description of the horrible slaughter on July 27, 1802 in the captured Russian fort is given in a letter from Ambrosiy Plotnikov, which was later found in the office of the Russian-American Company: “I saw one of our people jump out of the window of one of the burning buildings, but was seized by the savages’ knives and thrown back into the fire. I saw how they cut off the head of another person and threw the headless body into the fire.” 31 The captured Russians were rescued by the approaching British ships. Alfred Peter Swineford (1836–1909) wrote about this in his book Alaska: Its History, Climate and Natural Resources (1898), the fourth chapter of which was devoted to the activities of A.A. Baranov, war of 1802–1804, and other events [8, pp. 37–55].

After the Indians drove the Russians out of Sitka in 1802, the Tlingit shaman Stoonookw predicted that the Russians would return. He urged the clans to build a new fortification, strong enough to withstand cannon fire. The Tlingit chose the area near the river for their new fort, because it was close to food and fresh water, but out of range of naval artillery. Russian ships ap- peared at the mouth of the Indian River (Kaasda Heen) on September 28, 1804. The siege and several days of bombardment began. The Russian troops bravely came ashore in a frontal attack on the Fort Shis'qi Noow on October 1, 1804. The Tlingit managed to hold it. Hiding behind floating logs, the Kix.adi warriors counterattacked. Russian troops retreated into a siege to their ships. Neither the bombardment of the Tlingit fort, nor the attack on the fort caused them significant damage. Leader of Katlian penetrated the Russian camp several times and crushed everything with his war hammer. Two fatal events worked against the Tlingit — the unexpected arrival of the Russian frigate Neva and the loss of a canoe carrying their reserve ammunition and the most hardened warriors just before the battle. The Tlinglits fired on Russian ships with their cannons (falconets). The Neva ship, which had arrived, returned fire in heavy force, causing considerable damage to the Indians.

A painting from the Sitka National Historical Park brochure depicts a battle scene at the mouth of the Indian River (Fig. 8). In the foreground, Tlingit warriors are armed with long guns and spears. Some had protective wooden battle helmets and a thick wooden chest shield. The sturdy log wall in the right corner is part of a new fort built by the Tlingit for this battle. The leader of the battle, Catlian, wore a raven war helmet and gray fur around his bare torso. His weapon is a blacksmith's hammer, which he holds vertically in a striking position along with his other hand, leading a group of warriors onto the battlefield. It is raining arrows from the Aleuts. Behind them one can see the Sitka Strait with Russian ships and a stream of small canoes, accommodating one person at a time, and a mountain range.

Fig. 7. Battle with the Tlingit. Brochure at Sitka National Historical Park.

After a few days of defense, the Kix.adi Indians themselves left the fort and moved north to the strait. They established a trade blockade while continuing to hunt, fish and gather wild food in and around Sitka. The Battle of Sitka ended open Tlingit resistance, but the Russians were safe only as long as they were vigilant. A.A. Baranov personally survived several assassination attempts by local residents, defending himself with chain mail, which he constantly wore under his clothes.

The Russian-American company headed by A.A. Baranov returned after the war of 1802– 1804. Sitka Island, where Novo-Arkhangelsk was founded as a permanent settlement, named after the ancient city of Arkhangelsk at the mouth of the Northern Dvina, leading its history from the Mikhailo-Arkhangelsk Monastery from the end of the 14th century. In 1808, Sitka was declared the capital of Russian America. In 1821, the Russians invited the Tlingits back to Sitka (Tlingit-Sitka National Historical Park).

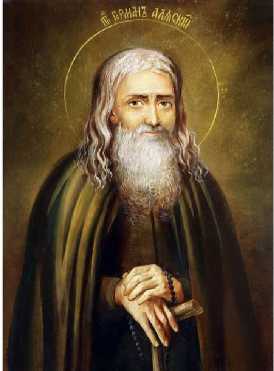

On the missionary work of Herman of Alaska

During the reign of A.A. Baranov and later, new settlements were being built in Russian America; industrial and craft production, culture, and religion were developing. The empress Catherine II took control over education in Alaska. In 1794–1796, the first Orthodox Church, the Cathedral of the Resurrection, was built on Kodiak Island. Hieromonks began to travel from island to island, preaching and baptising the Aleuts. In 1793, the monk Herman (secular name — Yegor Ivanovich Popov) began missionary work as part of the Kodiak spiritual mission (1751–1836). He was tonsured a monk on Valaam on October 22, 1782. From 1807, Father Herman became the de facto head of the Kadiak Mission, enduring the hard conditions of life, and continuing to tirelessly baptize, educate and protect the local population.

Fig. 8. Saint Herman of Alaska

During the reign of Baranov, Orthodoxy was accepted by more than nine thousand local residents. Church ministers contributed greatly to the spread of literacy among Alaska natives 33.

Many Alaskan natives today still have Russian surnames, honor their Russian ancestry, and remain faithful to the Russian Orthodox Church, the only public institution left from the period preceding 1867. In the 1960s, membership in indigenous associations required issues of affiliation to this status to be resolved. It was resolved by means of Orthodox Church records [10, R. Pierce, pp. 12– 15]. Several old Russian settlements in Alaska, where the churches of the Russian Orthodox Church existed from the end of the 18th century till 1867, disappeared over time.

Three assessments of nature of Russian colonization, N.P. Rezanov’s RAC modernization plan

There are at least three assessments of the nature of Russian colonization. According to one of them, Russian colonization was milder and more progressive with regard to the native population than Spanish, English or American colonization , and among the methods of exploitation of the natives, the capitalist system of free hire and unequivalent trade exchange prevailed [3, vol. 1, p. 115] 34. Free Aleuts and Tlingits received beads, necklaces, various kinds of clothing and tobacco for the furs harvested in the offshore fishery at very high prices, compared with the low rates for furs. The goods offered to the Tlingit were quite expensive due to the chronic shortage of European manufactured goods in the Russian colonies, which, in turn, was the result of irregular supply, high transport costs and abuses of officials responsible for supplying the necessary goods to Russian settlements Alaska. Goods, offered to the Indians, were also bought by the Russians on British or American ships. American skippers sold guns and even light cannons to the Tlingit [5, pp. 112– 114]. At the same time, “ Never and nowhere did the Russians, when communicating with the natives, emphasize any superiority of the white race. This is absolutely not characteristic of the historically developed character of the Russian people ”, N.N. Zubov believed [4, p. 133] .

Secondly, the Russian colonization of the North-West of America, as well as the colonization of the English, Spanish or French, according to the RAS academician N.N. Bolkhovitinov, was inextricably linked to violence, deception and exploitation of indigenous people [3, vol. 1, p. 22]. Methods of forced labor varied from the development of new needs among the natives, free employment and economic enslavement. A very effective means of reconciliation and subjugation of the indigenous population was the practice of taking hostages. As a punishment they transferred to the lowest rank, and those who committed serious crimes were severely beaten and driven “through the ranks”. For the Aleuts and Kodiaks, this was such a shameful punishment that those who endured it often committed suicide. Such a case, for example, was mentioned in one of Bara- nov's letters, which spoke of the punishment of two mushers for the murder of the industrialist Dmitriev in 1794. The concentration of industrialists and natives in permanent Russian settlements depleted the flora and fauna in the area. This often caused starvation and exacerbated the already intractable problem of food supply for the Russian colonies in America. “We don’t need gold here as much as we need provisions”, Baranov wrote to the owners of his company [3, vol. 1, pp. 116– 117]. In order to provide themselves with the necessary supplies of food and furs, the Russians deprived the natives of part of their fishing grounds. The dispersed settlement of aborigines, which provided a relatively uniform load on natural resources, was disrupted after the arrival of the Russians.

The third assessment of the RAC activities was to recognize the fact that Russia actually laid the foundation for the economy in Alaska . “The best that can be said in defence of colonial rule is that it introduced the local population to the modern world. In fulfilling this function, the Russian colonial regime was in many respects softer than other colonial regimes in the New World or elsewhere” [10, Pierce R., pp. 12–15]. Professor of History Richard Austin Pierce (1918–2004) contributed to the publication of more than 60 volumes of Alaskan history as an author, translator, editor, and publisher and was considered one of the leading authorities in Russian America 35. In his report at the Alaska History Conference in Anchorage on the 100th anniversary of the purchase of Alaska by the United States (1867–1967), he stated that Russia had laid the foundation for the Alaskan economy. Its settlers made the first successful attempts to develop agriculture, began exploiting forest and fish resources. Geologists undertook the exploration of mineral resources, especially coal, which was mined on the Kenai Peninsula. Fur production was carried out from the early days of Russian domination and played a significant role in world markets. In the last period of Russian history, measures were taken to protect fur resources. In addition, shipping traffic was developed along the north-west coast of America, transport links were established between distant Russian factories and other settlements and commercial relations established with Victoria, San Francisco and other centres [10, Pierce R., pp. 12–15].

Р. Peirce believed that it was not difficult to show that Russian America deserved the best historical assessment. Hundreds of Russian geographical names are preserved on the map of Alaska, and one need only look at the maps of G.A. Sarycheva, I.F. Vasilyeva, M.D. Tebenkova, A.F. Ka-shevarov and others to see that the winding coastline of Alaska was well known to Russian navigators. Russian maps of Alaska after 1867 became the basis for American maps. Knowledge about Russian America is of practical value to this day. They are significant in border issues, the problems of seal hunting on the high seas, in matters of citizenship, the legal regulation of hunting and fishing of Alaska natives. Modern ethnographers and ethnohistorians regard the ship logs and docu- ments of the Russian period as invaluable historical information about the Alaskan Native culture at the time of the first contacts with Europeans. [10, Pierce R., pp. 12–15].

N.P. Rezanov’s RAC modernization plan

The modernization policy of the Russian-American Company is represented by secret instructions of the diplomat, traveller, count N.P. Rezanov (1764–1807), who, together with his father-in-law, industrialist and merchant G.I. Shelikhov, was at the origin of RAC, spoke five European languages and was the first official Russian ambassador to Japan.

Fig. 10. N.P. Rezanov.

N.P. Rezanov had drafted a set of secret instructions for A.A. Baranov in July 1806, shortly before his untimely death 36. He recommended improving shipbuilding and crew training, establishing an agricultural colony in the new Albion (Northern California), creating a permanent Russian population, introducing a regional currency, and building schools and medical facilities. In terms of its content, in fact, it was a plan or a brief socio-economic program for the modernization of all Russian America, which logically followed from the mission of the RAC itself, which combined the functions of state administration in the territories of North America with private initiative, entrepreneurship, traditional trade and fishing functions and the creation of an appropriate infrastructure.

N.P. Rezanov, going from the Far East to St. Petersburg, caught a cold on the way, died and was buried on March 13, 1807 in Krasnoyarsk at the cemetery at the Resurrection Cathedral 37. In 2000, at the site of the alleged reburial of the commander, the main character of the rock opera “Juno and Avos”, a marble cross was set up with the inscription: “Kamerger Nikolay Petrovich Rezanov. 1764–1807. I will never see you again”, and below: “Maria de la Concepción Marcela Ar-güello. 1791–1857. I will never forget you”. The sheriff of Monterey scattered a handful of earth from Conchita’s grave over the grave. He took back a handful of Krasnoyarsk earth to scatter over her grave.

In Alaska, public libraries, schools and hospitals, and nursing homes for the elderly were opened. The first Russian school was opened on Kodiak Island in 1784–1786 on the orders of G. Shelikhov. In 1805, it was transformed into a school by order of N. Rezanov. Many books, magazines and paintings were delivered from St. Petersburg to the library on Kodiak. Teenagers at school were taught not only Russian, but also French, not only crafts, but also geography and mathematics. The RAC inventory of 1815 listed the main territories, buildings, population and capital under the control of the Russian-American Company, including settlements on Kodiak Island, in Novoarkhangelsk, Fort Ross in California, and also an island that was supposed to be bought from the King of Hawaii 38. A popular song in Alaska was the hymn “Mind of Russia has started a trade, free Russians on the seas, to explore places, to seek benefits”, composed by A.A. Baranov long before the appearance of “God Save the Tsar” 39.

In the archive list of the number of Russians and natives born in America and the islands by Russian and native women, who are in the service of the RAC, there were listed 645 people in 1818 (491 men and 154 women). The number of local residents is determined at 8448 people. Most of the autonomous Russian population (80%) were engaged in administration, defence and service to ships, and the fur trade itself was dealt with by quite a limited number of people [3, vol. 2, p. 430]. Russian people, crossed the ocean, thoroughly settled in the New North. Sailors brought breadfruit from Oceania to Novoarkhangelsk. Spanish silver rang in Alaska, women baked bread from Californian flour, men drank rum and wine from Chile and Peru, smoked tobacco from the West Indies. In California, the Russian fort Ross, founded by Ivan Kuskov, flaunted, and his people walked upstream the rivers that flowed into the Gulf of St. Francis. Strong ties were established even with the Hawaiian Islands, King Tamehamea I presented Baranov with a piece of fertile land [1, p. 16].

In Russian America, high-tech shipyards and agricultural production, brick and iron foundries functioned, coal mining was organized, modular wooden houses were made for transportation to other regions 40. In the 18th–19th centuries, different wooden buildings, which had a lot in common with the buildings of the Russian North, were characteristic not only for the white settlers, but also for the Indian tribes that lived in these places. Sedentary fishing Indian tribes, for example, built dwellings that resembled log huts. In Russian America, the RAC signs were in circulation — banknotes that were made of leather, dyed in various colors according to the denomination, with the RAC stamp on one side and the denomination on the other [5, p. 293]. To carry out the “sea animal” fishing, connections with neighbouring countries and metropolis, the Russian-American Company built and bought 32 vessels, spending 3.3 million rubles on this. Of the 13 ships, remaining by 1818, 5 were built in the colonies themselves, 4 were bought from the “Bostonians”, the brig “Finland” was built in Okhotsk, the American ship “Kutuzov” was bought in France, and 2 more American ships were purchased in Kronstadt — “Suvorov” and “Rurik”. In general, for 1797–1818, the company gained 16 376 695 rubles from the fishing of furs, walrus bones, whalebones, etc. or 818 835 rubles per year [3, vol. 2, pp. 430–431].

The Decembrists were at the origin of the idea to develop virgin transoceanic lands. Kon-draty Ryleyev was the governor of the main board office of the Russian-American Company. In 1822, Mikhail Kuchelbecker travelled to Russian America; Nikolai Bestuzhev, Zavalishin, Pestel took an active part in its fate and affairs. It is no coincidence that the Tsar Nicolas I, when questioning the member of the rebellion Orest Somov, who also took part in the RAC affairs, jealously said: “It’s good that you created a company there” [1, p. 19, 24, 36].

The energetic Russian leader, who established schools in Russian America, erected fortresses, built shipyards and launched Russian ships, admired A.S. Pushkin. When A.A. Baranov, who had many enemies in cruel Russia of Nicholas, was removed by slanderous libel from his post, remained in poverty and died on the way back to Russia, was buried in the water, Pushkin wrote in his Kishinev diary: “Baranov died. It's a pity for an honest citizen, a smart person” [11, p. 306]. M.V. Lomonosov has such lines: “The Columbuses of Russia, despising gloomy fate. Between the ices, a new path will be opened to the east. And our power will reach America” [12, p. 703]. Baranov A.A. and Shelikhov G.I. undoubtedly belong to the number of such discoverers.

Robin Joy Wellman, an employee of Fort Ross State Historical Park, Alaska, using literature and a number of documents, presented his vision of Baranov's personal qualities as a man, leader and nobleman, his role in the history of Russian America and Fort Ross. He noted the significance of the name of Arkhangelsk for Russian America. R. Wellman assessed Baranov as a benefactor, sometimes ruthless, who faced great difficulties, lack of RAC support, became a real loner, his own leader, could not rely on anyone, was even deprived of decent food. “He gained the respect of the natives for the most part, depended on them when hard times came, and he soon became dependent on the children who grew up around him, the Creoles” [6, pp. 332–335].

Novo-Arkhangelsk had a serviceable arsenal, observatory, library, 2 hospitals, sawmill, watermill, club house, pier on a stone foundation, 3 barracks for single and married workers and military seamen. The RAC had 8 ships, including a steamer with fourteen cannons for the straits. Outside and inside the fortress, even while eating or sleeping, each of his team had to carry a gun with him. And when everyone was drinking, A. Baranov used to say: “drink, but know your business” and suddenly announced the alarm [13, pp. 53–56].

S.N. Markov wrote that Baranov was sometimes heavy-handed. Under his leadership, “on the hardened land and on the islands” of America, there were about two hundred Russian industrialists and a thousand Creoles — people born from mixed marriages with Indians, Aleuts and Eskimos. Among these subordinates were those who “were matured in barbaric cruel customs”, and they had to be “warned and brought to knowledge” on occasion. Along with the industrialists, “violent seekers of easy money and adventures penetrated the Aleutian and Kuril Islands, for whom “gunpowder and vodka” were the only means of their communication with the locals. They did not recognize any power over themselves [4, p. 125]. A well-known fact is that a group of disgruntled colonists, led by the exiled convict Vasiliy Naplakov and the convict's son Ivan Popov, organized a secret society in Novo-Arkhangelsk with the intention of killing Governor A. Baranov, seizing the ship and taking away all the women colonies on the islands of the South Sea to create their own republic in 1809. Upon learning of the conspiracy, Baranov investigated the case and sent the five most culpable men to Kamchatka for prosecution 41.

During the years of his reign, A.A. Baranov made a lot of dissatisfied not only among the local population, but also among American, British, Russian merchants and industrialists. Defending the interests of Russia, he practically competed with the interests of the American, British and Spanish governments. There were permanent conflict situations with high-ranking shareholders and members of the board within the RAC itself.

In November 1817, Lieutenant Commander L.A. Gagemeister (1780-1833), commander of the RAC ship “Kutuzov”, arrived in Alaska. After analyzing the activities of A.A. Baranov, he dismissed him in January 1918. However, during the official verification, A.A. Baranov’s abuses were not identified. On the contrary, his disinterestedness was noted. Instead of 4.6 million, the balance of the RAC amounted of 6.8 million rubles. At the same time, for some reason, there is no correspondence of A.A. Baranov for 1803–1817. [14, pp. 212–216].

A.A. Baranov was not a saint, perfect ruler of Alaska in every respect. He consistently acted in the interests of Russia, managing the RAC, not for his own enrichment. The fate of A.A. Baranov and his second family is tragic. A.A. Baranov, after his resignation, was forced to leave Sitka and to go to St. Petersburg. However, it was not the usual overland route via Siberia, but a long sea voyage from Sitka to Kronstadt via Pacific and Indian oceans around the Cape of Good Hope. During the transition, A.A. Baranov fell ill and died in April 1819. His body was lowered into the abyss of the sea. There is no grave of Alexander Baranov left on Earth. After this, the life and fate of his second wife Anna Grigoryevna and their children turned out to be unhappy and short. His son Antip- ater died on March 8, 1822 (1797–1822). After his death, the 200 roubles a year pension he had obtained for his mother, was abolished by another governor of the RAC, M.I. Muravyov 42. Anna Grigoryevna died in 1823 in the monastery, having outlived her son by only a year. Irina (1802– 1824), the daughter of Alexander and Anna Baranovs, died soon after. There is not enough information about another daughter Catherine (1808–?). It is not clear where and how the will and other documents of A.A. Baranov disappeared. His family found themselves without acquired capital and largely depended on RAC charity.

Russian sale of Alaska to the United States

History was, is and remains a subject of geopolitical struggle, shaping public opinion even in the 21st century. One of the speculations in society was the issue of the sale of Alaska, quite well researched by now. Covering the history of Russian Alaska, it is necessary to touch upon it, at least very briefly, in this article to understand the historical meaning of the relationship between Russia and the USA in the 19th century, to show not only the beginning, but also the end of Russian Alaska. The Russian-American Convention, which regulated relations between Russia and the United States on the American continent, was concluded on April 5/17, 1824. A similar convention between Russia and Great Britain dates back to February 16/28, 1825. Both agreements determined the boundaries of Russian possessions and became the first international acts establishing Russia's ownership of both the Aleutian Islands and part of the territory on the American mainland 43. RAC activities on the eve of the sale of Alaska to the United States in 1858–1867 are analyzed by A.Yu. Petrov 44. With his participation, the circumstances of the sale of Alaska were publicly discussed on September 09, 2018 45.

Alaska was sold as a result of a deal between the governments of the Russian Empire and the United States in 1867 for $7.2 million in gold. The signing of the treaty took place in Washington on March 18/30, 1867. Emperor Alexander II signed the treaty on May 3 (15), 1867, and the Senate adopted a decree on the execution of the treaty on October 6 (18), 1867. Together with a territory of 1 million 519 thousand sq. km of the USA, all real estate, all colonial archives, official and historical documents were transferred. Residents of these territories received the right to re- turn to Russia within 3 years or, if desired, remain in the United States 46. The Russian flag was lowered in Novo-Arkhangelsk.

When deciding to sell Alaska to the United States, the Russian government was guided not only by financial, but also by geopolitical considerations. It was argued that the transfer of the colonies would relieve possession, which in case of a war with one of the maritime powers, Russia could not fully protect, that the treaty would help strengthen the alliance between Russia and the United States, etc.

Conclusion

History has always been and will remain the subject of constant discussion at all times and in any society. Today, history is increasingly transforming into politics, acquiring geopolitical meaning. For sober-minded people, it is an axiom that time cannot be turned back. History, unlike politics, cannot be changed, no matter what you do today: demolish monuments in the United States, as was done in 2020, distort facts about the role of the USSR in the Great Victory of 1945, and invent other historical fakes. No one in this world will ever stop the ships of Christopher Columbus going to America in the past, will not change the activities of A.A. Baranov, as the main ruler of Russian settlements in America.

The connection of the past and present in relation to the development of Russian Alaska and the famous historical figure A.A. Baranov highlighted the most difficult problem of an ambiguous attitude to the historical past from the standpoint of the US politics and modern geopolitics. The political process of the destruction of monuments in the United States under the onslaught of the Black Lives Matter movement has quite expectedly reached Alaska. The local Indian population accused Alexander Baranov, who had long gone to another world, of racism and the persecution of the indigenous population. The Sitka City and District Assembly decided to remove the monument to A. Baranov from the city square and transfer it to the museum.

Russian colonization of Alaska in the 18th and 19th centuries was primarily aimed at taking economic advantage of its natural resources, but did not set the destruction and humiliation of the indigenous peoples of the United States (the Aleuts, Indians, Eskimos) as its goal, the superiority of the white race was not emphasized. European culture, religiosity, civilization and pragmatism in the settlement of vast territories of North America in the 18th–19th centuries came with the Russians. The Russian history of Alaska is covered today as “colonial legacy” in North America. Obviously, there is a need for a comparative analysis of the colonial heritage not only of Russia, but of Spain, Great Britain, the USA and other countries on the American continent.

Список литературы About Russian Alaska and Its Ruler A.A. Baranov

- Markov S.N. Letopis' Alyaski [Chronicle of Alaska]. In: Izbrannye proizvedeniya. Tom 1 [Selected Works. Volume 1]. Moscow, Khudozhestvennaya literatura Publ., 1980, 675 p. (In Russ.)

- Golder F.A. Russian Expansion on the Pacific, 1641–1850: an Account of the Earliest and Later Expe-ditions Made by the Russians Along the Pacific Coast of Asia and North America, Including Some Re-lated Expeditions to the Arctic Regions. Cleveland, A.H. Clark Publ., 1914, 382 p.

- Bolkhovitinov N.N. Istoriya Russkoy Ameriki (1732–1867): v 3-kh tomakh [History of Russian Ameri-ca (1732–1867): in 3 Volumes]. Moscow, Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya Publ., 1997; Vol. 1. Osno-vanie Russkoy Ameriki, 1732–1799 [Founding of Russian America, 1732–1799]. Moscow, Mezhdu-narodnye otnosheniya Publ., 1997, 479 p.; Vol. 2. Deyatel'nost' Rossiysko-amerikanskoy kompanii, 1799–1825 [Activities of the Russian-American company, 1799–1825]. Moscow, Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya Publ., 1999, 472 p.; Vol.3. Russkaya Amerika: ot zenita k zakatu, 1825–1867 [Russian America: From Zenith to Sunset, 1825–1867]. Moscow, Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya Publ., 1999, 560 p. (In Russ.)

- Zubov N.N. Otechestvennye moreplavateli — issledovateli morey i okeanov [Domestic Sailors — Ex-plorers of the Seas and Oceans]. Moscow, Paulsen Publ., 2014, 474 p. (In Russ.)

- Grinev A.V. Indeytsy tlinkity v period Russkoy Ameriki (1741–1867 gg.) [Tlingit Indians during the Pe-riod of Russian America (1741-1867)]. Novosibirsk, Nauka Publ., 1991, 318 p. (In Russ.)

- Reshetnikov N.I., Tormosova N.I. Kargopol' i Russkiy Sever v istorii i kul'ture Rossii. X-XXI vv. Materi-aly XIV Kargopol'skoy nauchnoy konferentsii (15–18 avgusta 2016) [Kargopol and the Russian North in the History and Culture of Russia. X-XXI Centuries. Proc. 14th Kargopol Sci. Conf. (August 15-18, 2016)]. Kargopol, 2017, 407 p. (In Russ.)

- “Pod rossiyskim nebesnym flagom...”: Russkaya Amerika, 1787–2012: rekomendatel'nyy biblio-graficheskiy ukazatel': k 200-letiyu osnovaniya kreposti Ross (Fort Ross, 1812): k 270-letiyu otkrytiya Russkoy Ameriki — Alyaski (1741–1742) [“Under the Russian Sky Flag...”: Russian America, 1787–2012: Recommended Bibliographic Index: to the 200th Anniversary of the Foundation of the Fort Ross (Fort Ross, 1812): to the 270th Anniversary of the Discovery of Russian America – Alaska (1741–1742)]. Moscow, TsUNB im. N.A. Nekrasova Publ., 2013, 76 p. (In Russ.)

- Swineford A.P. Alaska: its history, climate and natural resources: with map and illustrations. Rand, McNally & Co. Publ., 1898, 256 p.

- Krymskaya T. German Alyaskinskiy, pravoslavnyy svyatoy [Herman of Alaska, Orthodox Saint]. Kadom Publ., 2019, 37 p. (In Russ.)

- Pierce R.A. Istoriografiya Russkoy Ameriki: problemy i zadachi [Historiography of Russian America: Problems and Tasks]. Vologda, 1993, no. 2/3, pp. 12–15. (In Russ.)

- Pushkin A.S. Sobranie sochineniy: v 10 t. [Collected Works: in 10 Volumes]. Moscow, Goslitizdat Publ., 1959–1962. Vol. 7: Istoriya Pugacheva: Istoricheskie stat'i i materialy. Vospominaniya i dnevniki [History of Pugachev: Historical Articles and Materials. Memories and Diaries], 1962, 463 p. (In Russ.)

- Lomonosov M.V. Polnoe sobranie sochineniy. Tom vos'moy / Petr Velikiy. Geroicheskaya poema. Pesn' pervaya [Full Composition of Writings. Volume Eight / Peter the Great. Heroic poem. Song One]. Moscow, Leningrad, AN SSSR Publ., 1959, pp. 696–734. (In Russ.)

- Markov A.N. Russkie na Vostochnom okeane: Puteshestvie Al. Markova [Russians on the Eastern Ocean: The Journey of Al. Markov]. St. Petersburg, A. Dmitriev's Printing House Publ., 1856, 263 p. (In Russ.)

- Baskakov E.G. Dokumenty Rossiysko-Amerikanskoy kompanii v Natsional'nom arkhive SShA [Docu-ments of the Russian-American Company in the US National Archives]. In: Istoriya SSSR [History of the USSR], 1963, no. 5, pp. 212–216. (In Russ.)