Agility assessment test in wheelchair basketball players - a sistematic review

Автор: Stojanović S., Hadžović M., Ilbak I., Lilić A., Jorgić B., Ilić T.

Журнал: Sport Mediji i Biznis @journal-smb

Статья в выпуске: 3 vol.11, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Wheelchair basketball is one of the most widely represented sports among Paralympic disciplines and is practiced by individuals with various physical impairments. Agility is defined as a rapid whole-body movement involving a change in velocity or direction in response to a sport-specific stimulus. Based on this definition, agility in wheelchair basketball refers to the ability to execute fast changes of direction with the sports wheelchair. Players must possess adequate levels of speed, agility, and strength to perform complex game tasks effectively. Performance analysis of elite wheelchair basketball players is considered essential, as it provides evidence-based guidelines for training optimization and competition preparation. The aim of this paper was to conduct a systematic review of agility assessment tests used in wheelchair basketball players. Literature was collected through the following scientific databases: Google Scholar, PubMed, and Web of Science. A total of fifteen original research studies (N=15) met the inclusion criteria. The analysis indicated that the most commonly applied agility tests include slalom tests with or without a ball, ball pick-up test, Illinois agility test, T-test, figure-eight with ball, 3–6–9 m drill test, and zig-zag agility tests performed with and without the ball.

Wheelchair basketball, agility, change of direction, performance testing

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170211429

IDR: 170211429 | УДК: 796.323.2.012.21-056.266; 796.323.2.034-056.266 | DOI: 10.58984/smb2503055s

Текст научной статьи Agility assessment test in wheelchair basketball players - a sistematic review

DOI:

Wheelchair basketball (WB) has been played since the 1940s (Kasum, 2015) and remains one of the most popular Paralympic sports among athletes with different types of physical impairments. It has been included in the Paralympic programme since the first Games held in Rome in 1960 (Milenković & Živanović, 2010). The rules of WB largely correspond to those of conventional basketball, including basket height, free-throw line, scoring lines, and court size (Kozomara, Petrovic, Nikolic, & Jor-gic, 2019). Two teams of five players compete, and the match lasts four ten-minute periods (International Wheelchair Basketball Federation, 2017). The key difference is that athletes perform all game actions in sports wheelchairs. To ensure fair competition, players undergo a functional classification system in which each athlete is assigned a point value based on functional abilities (Kozomara et al, 2019). Eligibility typically requires an impairment that limits lower-limb function, meaning that athletes cannot run, pivot, or jump in the same manner as in conventional basketball (Јоргић, Александровић, Мирић, Чоловић, & Димитријевић, 2020). WB is currently played at a competitive level in more than eighty countries (Gómez, Javier Pérez, Molik, Szyman, & Sampaio, 2014). Consequently, scientific interest in this sport has increased, contributing to improved training loads and more specific conditioning approaches. Research has examined physiological, biomechanical, psychological, and tactical variables associated with successful performance (Gómez et al, 2014; Croft, Dybrus, & Lenton, 2010; Martin, 2008), providing coaches with applied guidance for training design. In addition to these factors, motor abilities also substantially influence WB performance (Goosey-Tolfrey, & Leicht, 2013). From a physiological perspective, WB is an aerobic–anaerobic sport that combines repeated high-intensity sprints, accelerations, and rapid changes of direction with moderate- and low-intensity actions aimed at scoring or maintaining effective court position (Molik, Laskin, Kosmol, Skucas, & Bida, 2010). Both anaerobic and aerobic capacities appear important for offensive and defensive effectiveness (Molik, Laskin, Kosmol, Marszalek, Morgule-Adamowicz, & Frick, 2013). Accordingly, WB players are expected to demonstrate optimal speed, agility, strength, endurance, coordination, and well-developed technical and tactical skills. Performance analysis of elite athletes is therefore essential for evidence-based training improvements and competition preparation (Wang, Chen, Limroongreungrat, & Change, 2005). Fitness and motor ability assessment also supports longitudinal monitoring, evaluation of training effectiveness, and can assist in player selection (Drinkwater, Pyne, & McKenna, 2008). Because motor abilities contribute to individual and team success (Riezebos, Paterson, Hall, & Yuhasz, 1983), their assessment may improve the prediction of team performance, although wide variability in impairment profiles can influence the capacity to develop specific abilities, reinforcing the rationale for classification (Drinkwater et al, 2008). The sport is characterized by intermittent high-intensity actions, particularly wheelchair maneuvering and ball handling (Coutts, 1992). Wheelchair maneuvers include rapid starts, stops, and changes in direction, which require speed, strength, and agility. Agility is defined as a rapid whole-body movement involving a change in speed or direction in response to a sport-specific stimulus (Sheppard, Young, Doyle, Sheppard, & Newton, 2006). Within WB, this definition may be interpreted as the capacity to change wheelchair direction quickly and efficiently. Ball-handling actions include shooting, passing, dribbling, rebounding, and overhead shooting while simultaneously controlling the wheelchair, indicating that upper-extremity strength is a key determinant of agility performance in wheelchair athletes (Wang et al, 2005). In WB, one hand is often used for propulsion or maneuvering while the other controls the ball, which further increases the technical and physical demands of agile movements (Frogley, 2010). Moreover, lateral mobility while moving a wheelchair is reduced compared with running, which shapes tactical strategies such as blocking the opponent’s intended movement path. Therefore, high-level wheelchair skill-related agility is required for optimal performance (Frogley, 2010). During WB, players continuously respond to opponents, teammates, and the ball. As previously noted, more agile players are likely to reach advantageous positions closer to the basket, which may increase scoring opportunities (Yanci, Granados, Otero, Badiola, Olasagasti et al., 2015). In defensive play, agility may enable athletes to restrain opponents further from the basket, reducing high-percentage shots and lowering the opponent’s score (Yanci et al., 2015). Given the importance of agility for success in WB, valid agility tests are required to determine current ability levels, evaluate training effects, and compare players or teams. Studies have already examined the validity and reliability of agility tests in wheelchair basketball players (De Groot, Balvers, Kouwen-hoven, & Janssen, 2012;

Methods

Review design

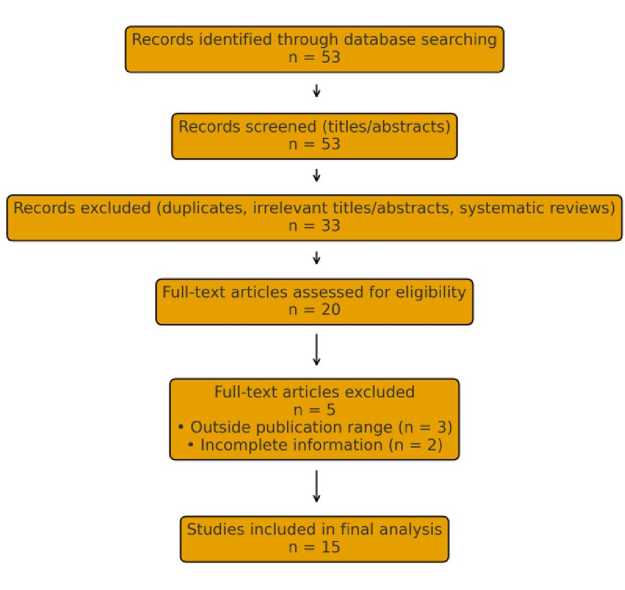

A systematic review of the literature was conducted to identify and synthesise evidence on agility assessment tests used in wheelchair basketball players. The methodological approach was structured to ensure transparent reporting of information sources, study selection procedures, and data synthesis consistent with expectations in international sports science journals.

Information sources and search strategy

Electronic searches were performed in Google Scholar , PubMed , and Web of Science . Studies published between 2012 and 2025 were considered. The search strategy combined terms related to wheelchair basketball and agility testing. The following keywords were used in various combinations: wheelchair basketball , agility , validity , reliability , effects . To identify additional potentially relevant studies, the reference lists of all eligible full-text articles were manually screened.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following conditions: (a) the study was written in English or Serbian; (b) wheelchair basketball players were examined; (c) agility was assessed through clearly described measurement instruments; and/or (d) the study investigated changes in agility or reported tests used for agility assessment; and (e) sufficient methodological detail was provided to allow interpretation of test procedures and outcomes. Full-text availability in English or Serbian was required. Studies were excluded if they were systematic reviews, if they were not published in English or Serbian, or if they did not report data relevant to agility tests in wheelchair basketball players.

Figure 1 . Study selection, analysis, and exclusion process.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts identified through database searches were screened for relevance. Potentially eligible papers were then assessed in full text. This two-stage selection process was implemented to ensure that only original studies with adequate methodological information on agility testing in wheelchair basketball were included.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from each included study using a structured approach. The following information was recorded where available: sample size, sex, competitive level, player classification, test name and protocol, and reported outcomes related to agility performance. When studies provided reliability or validity outcomes, these were also extracted. Additionally, relevant test-context information (e.g., wheelchair-related conditions and testing environment) was noted when reported, given its potential influence on agility performance.

Data synthesis

Considering the expected heterogeneity of protocols and reporting formats across studies, a narrative synthesis was applied. Agility tests were grouped according to their movement structure and sport specificity, with emphasis on tests involving wheelchair manoeuvring with or without ball-handling tasks. This approach enabled the identification of test types most frequently used in the assessment of agility among wheelchair basketball players.

Results

|

о «л £ га V Ш D > га —' |

Ji о. Е га (Л |

V -С +* > о = |

|

|

De Groot et al. (2012) |

n=9 WB (two teams) |

To examine validity and reliability of field-based performance tests in WB |

Slalom (w/ball, w/o ball); BPU |

|

Williams (2014) |

n=21 WB; 32.33±4.52 yrs |

To examine validity and reliability of tests for motor abilities in WB |

IAT |

|

Ayán et al. (2014) |

n=12 WB; 29.6±5.4 yrs |

To examine changes in motor abilities after one season |

Slalom (w/ball, w/o ball) |

|

Ozmen et al. (2014) |

n=10 WB; 31±4 yrs |

To examine effects of strength training on speed and agility |

IAT |

|

Yanci et al. (2015) |

n=16 WB; 33.06±7.36 yrs |

To assess speed, strength, agility, and cardiorespiratory capacity in WB |

T-test |

|

о * «л £ ГО .h -м (U ш D > га —' |

Ji о. га СЛ |

Ф -С |

|

|

Iturricastillo et al. (2015) |

n=8 WB; 26.5±2.9 yrs |

To examine changes in body composition and performance across one season |

T-test; BPU |

|

Gil et al. (2015) |

n=13 WB; 33.30±8.01 yrs |

To examine physical fitness and validate field-based tests in WB |

BPU; T-test |

|

Yüksel et al. (2018) |

n=21 WB; 34.33±7.52 yrs |

To compare performance levels of players from different leagues |

Slalom (w/ball, w/o ball) |

|

Kozomara et al. (2019) |

n=6 WB; 20–47 yrs |

To examine changes in motor abilities after a preparation period |

Slalom (w/ball, w/o ball) |

|

Tachibana et al. (2019) |

n=37 female WB; 31.2±8.0 yrs |

To examine influence of functional classification on skill test outcomes |

Fig8-B; T-test |

|

Marszałek et al. (2019) |

n=9 WB; 29.7±5.9 yrs |

To examine validity and reliability of short, high-intensity field tests |

3-6-9; IAT |

|

Salimi et al. (2020) |

n=17 WB; 27.9±4.74 yrs |

To examine test–retest reliability of the Illinois test in WB |

IAT |

|

Weber et al. (2020) |

n=11 WB; 17–44 yrs |

To assess physical fitness in WB |

T-test |

|

Soylu et al. (2021) |

n=26 WB; 26.57±9.39 yrs |

To examine relationships between psychological characteristics and performance |

Slalom (w/ball, w/o ball) |

|

Ribeiro et al. (2022) |

n=37 WB; 20–31 yrs |

To examine associations between strength and agility |

ZigZ (w/ball, w/o ball) |

Legend: WB - wheelchair basketball players; yrs - years; w/ball - with ball; w/o ball without ball; BPU - ball pick-up test; IAT - Illinois agility test; T-test - T-test; Fig8-B - figure-8 with ball;

3-6-9 - 3-6-9 m drill test; ZigZ - zig-zag agility test.

Across the included studies, publication years ranged from 2012 to 2022, indicating sustained interest in agility assessment in wheelchair basketball over the last decade. Sample sizes were generally modest and relatively consistent, with the smallest sample reported by Kozomara et al. (2019) (n = 6) and the largest by Ribeiro et al. (2022) and Tachibana et al. (2019) (n = 37). Participants’ ages varied widely, spanning approximately 17 to 47 years, with the youngest sample observed in Weber et al. (2020) and the oldest in Kozomara et al. (2019). Most evidence was derived from male samples, as fourteen of fifteen studies included men, whereas only one study focused on female wheelchair basketball players (Tachibana et al., 2019). The agility assessment methods most frequently reported across studies included slalom tests with and without a ball, the ball pick-up test, the Illinois agility test, the T-test, figure-8 with ball, the 3-6-9 m drill test, and the zig-zag agility test with and without a ball, with all studies providing test-related data and describing testing procedures.

Discussion

The present review aimed to determine which agility assessment tests have been used in existing literature. After the literature analysis, fifteen original scientific studies investigating agility and agility testing in wheelchair basketball players were included. The review of fifteen original studies showed that agility in wheelchair basketball has been assessed using a range of field-based protocols, with the most consistently applied tests being slalom with and without a ball and the ball pick-up test. Additional frequently used measures included the Illinois agility test , T-test , figure-8 with ball , 3-6-9 m drill test , and zig-zag agility test with and without a ball.

Agility assessment in wheelchair basketball should be interpreted in light of the intermittent, high-intensity nature of the sport, where rapid accelerations, braking, and directional changes are continuously integrated with ball-handling demands (Coutts, 1992). Evidence suggests that agility performance is not an isolated capacity but is closely linked with sprint ability, strength, and endurance, indicating that test outcomes may reflect broader performance profiles relevant to both offensive and defensive efficiency (Yanci et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2005). Because functional classification is associated with differences in anaerobic and field-test performance, the interpretation of agility results should account for classification level to avoid misleading comparisons between athletes with different functional capacities (Molik et al., 2010; Gil et al., 2015; Tachibana et al., 2019). Validity and reliability data for commonly used protocols, such as slalom and ball pick-up tests, support their practical value, yet variations in testing conditions and protocol details may still influence comparability across studies and settings (de Groot et al., 2012; Vanlandewijck et al., 1999; Marszałek et al., 2019). An inspection of Table 1 indicates that various measurement instruments were used to assess agility in wheelchair basketball players. Starting with the oldest study included in this review, De Groot et al. (2012) applied two agility tests: slalom with and without a ball and the ball pick-up test. The same tests were used in other studies (Ayán et al., 2014; Iturricastillo et al., 2015; Gil et al., 2015; Yüksel et al., 2018; Kozomara et al., 2019; Soylu et al., 2021). Williams (2014) used the Illinois Agility Test modified for wheelchair basketball players. The agility course measures 10 m in length and 10 m in width. This test was also applied in other studies (Ozmen et al., 2014; Salimi et al., 2020; Marszałek et al., 2019). A relatively large number of studies used the T-test as an agility assessment instrument (Yanci et al., 2015; Iturricastillo et al., 2015; Gil et al., 2015; Tachibana et al., 2019; Weber et al., 2020). This test was standardised and modified for wheelchair basket-ball players following the model described by Yanci et al. (2015). The players begin from a static position with the wheels behind the start line facing cone A. After the signal, the athlete pushes forward as fast as possible to cone B and touches its top. The player then turns left and moves to cones C, B, and D (in that order), touching each cone before returning to cone A. Ribeiro et al. (2022) used the zig-zag agility test with and without a ball. This test is conceptually similar to the slalom test and can also be performed with or without ball handling. In addition to the T-test, Tachi-bana et al. (2019) applied a figure-8 agility test with ball handling. Upon the signal, the athlete manoeuvres the wheelchair while dribbling around two cones in a figure-eight pattern. Players were instructed to push as fast as possible while complying with International Wheelchair Basketball Federation (IWBF) dribbling rules. The cones were positioned 5 m apart. The time required to complete five laps was recorded. The test was performed twice, and the better time was retained. This modified figure-8 protocol was based on the model proposed by Vanlandewijck et al. (1999). Marszałek et al. (2019) used the 36-9 m drill test. In this test, players move as fast as possible over a 3 m distance and return to the start line, then repeat the same procedure over 6 m, and finally over 9 m. Overall, the findings indicate that multiple agility tests have been used to assess wheelchair basketball performance. To clarify the primary purpose of each test, the reviewed protocols may be grouped into several functional categories. Slalom with and without a ball, the ball pick-up test, the Illinois agility test, and the zig-zag agility test with and without a ball can be considered measures of curvilinear agility, as they involve changes of direction along a curvilinear path. The T-test and the 3-6-9 m drill test primarily assess lateral agility, although the Illinois agility test also includes segments that challenge lateral movement through combined linear and lateral wheelchair actions. Furthermore, slalom with a ball, the ball pick-up test, figure-8 with a ball, and zig-zag agility with a ball may be interpreted as tests of reactive agility, while zig-zag without a ball, slalom without a ball, and the Illinois agility test reflect non-reactive agility, as athletes follow a predetermined pathway without an external stimulus. After detailed analysis of the studies presented in Table 1, the most frequently used tests for agility assessment in wheelchair basketball players were: slalom with and without a ball, ball pickup test, Illinois agility test, T-test, figure-8 with a ball, 3-6-9 m drill test, and zig-zag agility test with and without a ball. A key limitation of this review is the restricted publication window and language framework applied during study selection, which may have resulted in the omission of relevant evidence published outside the defined period or in other languages.

Conclusion

Given the importance of agility for WB success, valid agility tests are necessary to accurately determine an athlete’s current ability, evaluate training effects, and compare players or teams. The main results show that the most commonly used tests were slalom with and without a ball, the ball pick-up test, the Illinois agility test, the T-test, figure-8 with a ball, the 3-6-9 m drill test, and the zig-zag agility test with and without a ball, with all included studies reporting test-related outcomes and describing assessment procedures. Future research should prioritise stronger protocol standardisation and examine how classification level and testing conditions influence the comparability of agility outcomes across studies and competitive contexts.

Conflict of interests :

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.