An elk figurine from Tourist-2, Novosibirsk: technological and stylistic features

Автор: Zotkina L.V., Basova N.V., Postnov A.V., Kolobova K.A.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.48, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Most fi gurines from the Bronze Age cemetery Tourist-2 in Novosibirsk are anthropomorphic, and follow one and the same iconographic style, termed “Krokhalevka”. Two fragments, however, refer to a zoomorphic image—that of an elk. As they cannot be refi tted, a special analysis was carried out. Computer-aided measurements and statistical comparisons suggest that they belong to a single specimen. This is important for further study, the search for parallels, and interpretation. Stylistic comparison with other items of portable art from Tourist-2 is diffi cult, since these are anthropomorphic. Nonetheless, the analysis suggests that the elk fi gurine is a perfect match with the homogeneous and stable technological complex revealed by other specimens. In terms of technology and style, the elk fi gurine parallels those of the Late Angara fi gurative tradition. Because the Tourist-2 burial had not been dated, a preliminary AMS-date of 4601 ± 61 BP (3511–3127 cal BC) was generated. Given this date and the archaeological context of the elk fi gurine, it can provide a reference point for the cultural and chronological attribution of other stylistically and technically similar images.

Stone fi gurines, technology, style, Bronze Age, Krokhalevka culture, rock art

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146043

IDR: 145146043 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2020.48.4.075-083

Текст статьи An elk figurine from Tourist-2, Novosibirsk: technological and stylistic features

Among the items of portable art from Tourist-2, representing mainly anthropomorphic images, a figurine of an elk made of shale was discovered. It is especially interesting in its similarity to other items of portable art from this site, which belong to a very specific motif-stylistic complex of the so-called Karakol-Okunev circle (Basova et al., 2017; Kolobova et al., 2019: 73; Basova et al., 2019). The context of this find was quite peculiar. While the rest of the items of portable art were found directly in graves, the fragments of the elk figurine were located outside the burial complexes. The shale at the place of fractures has crumbled, and the two pieces do not fit with each other.

The settlement of Tourist-2 is located on the abovefloodplain terrace of the right bank of the Ob River, 1.3 km north of the modern mouth of the Inya River, in the central part of Novosibirsk. The site was studied by excavations in 1990, and even then a long-term technogenic impact on the territory of the site of cultural heritage was noted (Molodin et al., 1993: 6–7). During the 2017 rescue fieldworks, carried out in connection with the development of the embankment, an Early Bronze Age burial ground was discovered, which included 21 flat graves. All the deceased were laid in an extended position on their backs (Basova et al., 2017: 510). Some of the graves contained Krokhalevka ceramics, which made it possible to attribute the entire complex of portable art to this culture (Basova et al., 2019: 54; Molodin, 1977:

Pl. LXIV, 1; LXVI, 3, 4; Bobrov, Marochkin, 2016; Polosmak, 1978, 1979). The site has been completely excavated. The uncovered area was 6040 m2, the collection of artifacts recorded in 2017 totals 10,394 items. The overwhelming majority of items identified in the settlement assemblage belong to the Krokhalevka culture. The stylistic and iconographic unity of the items of portable art against the background of a clear cultural and chronological context of the finds made it possible to identify the figurative style as “Krokhalevka” (Basova et al., 2019).

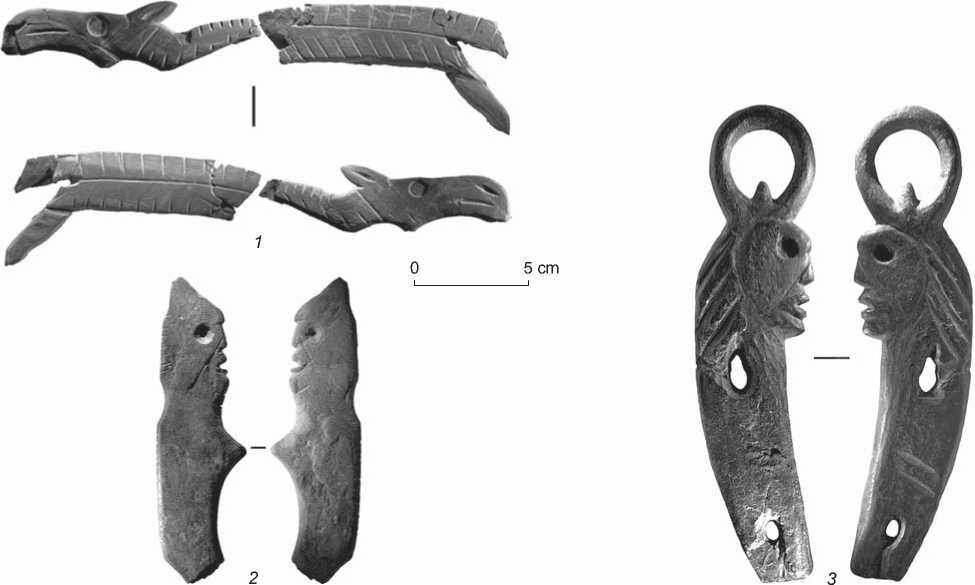

Two fragments of presumably the same figurine of an elk (Fig. 1, 1) were found together, lying one on top of the other, on the territory of the burial ground, outside the grave (excavation area, sq. 101/364). They are identical in terms of raw material, texture, and color; and both show very similar processing techniques. These considerations made it possible to assume that they constituted one item—a two-sided flat figurine of an elk. The length of the item, taking into account the missing fragment, was about 22 cm, width (along the body) 2.9 cm, thickness about 0.4 cm (Basova et al., 2019: 59, fig. 8). The items were found while exposing the baulk. Stratigraphically, their occurrence was traced at the very top of the cultural layer, at the point of contact with the technogenically altered lithological formations. Since this area of the site has undergone intense man-made interventions, it can be assumed that the fragments of an elk figurine were in the grave, like other items of portable art; but the burial was destroyed by the equipment, and the fragments of the figurine remained in the depression. Their arrangement one on top of the other may indicate that these items were not re-deposited as a result of earthworks, since such an intervention would undoubtedly separate them. As the excavations showed, part of the burial ground was destroyed. Fragments of human bones that were located not in anatomical order (along with randomly scattered artifacts lying in the same layer with modern debris) were recorded in these technogenically altered layers.

It can be assumed that the fragments of the elk figurine belonged to the settlement of the Krokhalevka culture, but this is unlikely, since below them there were no archaeological finds of this settlement, and the fragments lay at the same level as the grave goods. In addition, their location (one on top of the other in the same orientation) barely corresponds to the spatial distribution of finds in a settlement with a characteristic scattering of fragments of one item. However, one cannot completely rule out the possibility that fragments of the elk figurine constituted a treasure, as well as the likelihood of their belonging not to one, but to different sculptures. This issue requires special study.

The assemblage of items of portable art from the Tourist-2 burial ground is one of the pivotal examples

Fig. 1. Items of portable art from the Tourist-2 site.

1 – figurine of elk made of shale; 2 – anthropomorphic image made of shale (burial 6); 3 – anthropomorphic buckle made of burl (burial 5).

for the comparative-stylistic and stylistic-technological analysis of samples of the visual art of the Early Bronze Age in Siberia (Ibid.: 53–65). If all other figurines from this site come from graves that can be dated by radiocarbon method, then the sculpture was found outside the grave. Thus, the context of the find demands an answer to the question of whether it belongs to a portable art complex from the Tourist-2 cemetery, which is quite homogeneous in terms of style and technology, as well as its comparison with other items of portable art with a reliable dating context (in graves).

It is necessary to determine the place of the considered elk figurine in the general picture of development of the ancient art style in the region. Earlier, a brief stylistic description of this image was provided, and several analogs were proposed; as a result, it was noted that the figurine has features of the Angara figurative tradition (Ibid.: 62). However, in order to answer the question posed above and to clarify the place of this sculpture within the Angara style, it is necessary to consider in more detail both the artistic and technological techniques of its creation.

To obtain reliable information about the age of the Tourist-2 site, a series of dates is needed. However, items of portable art found in a dated archaeological context are extremely rare in Siberia. Therefore, even one radiocarbon date is of great importance for obtaining an idea about the age of the considered figurine. An animal bone from burial 6 at Tourist-2 produced the first preliminary radiocarbon date of 4601 ± 61 BP (NSKA-2423). Its calibration in the OxCal 4.3 software (Bronk Ramsey, 2009), using the IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al., 2013), gave the intervals of 3511–3127 (1σ – 68.2 %) and 3622–3101 (2σ – 95.4 %) years BC. This date can be regarded as an important chronological reference, and makes the artifact in question one of the reference examples of the Early Bronze Age portable art in Siberia.

Methods

The study of the elk figurine from Tourist-2 was performed in two directions: a technological analysis and a search for stylistic parallels were carried out. To characterize the design techniques, the figurine was examined using an Olympus SZ2-ET binocular stereoscopic microscope (×8–56). Based on the data obtained, a technical drawing of all the identified traces of the artifact was made. The macro-photographs were remotely stacked using the indicated microscope and Nikon D750 camera, glued using Helicon Focus software. Notably, not only was the elk figurine analyzed, but also all the items of portable art from Tourist-2. This made it possible to speak about the degree of homogeneity of technological and figurative techniques of execution and about the place of the figurine under consideration in the assemblage.

To search for parallels, published materials on portable and rock art in the region were used. The study of technological and stylistic characteristics of items of ancient fine art as signs of the “plan of expression” (Sher, 1980: 25) is a very promising area. This approach allows us to identify important combinations of them, which are difficult to detect by examining only one of these aspects (see, e.g., (Molodin et al., 2019)).

In order to find out whether the two fragments (head and body) were parts of the same figurine, we used the method of determining the belonging of unrefitted fragments to one artifact. This method implies the study of scaled three-dimensional models on which high-precision measurements of the most stable metric parameter (in this case, thickness) are carried out. The samples are then compared using parametric (Student’s t-test) and nonparametric (Mann-Whitney U test) tests. If the fragments belong to the same artifact, the null hypothesis will be confirmed, asserting the homogeneity of the statistical samples. This method allows us to derive an unambiguous answer (Kolobova et al., in press).

Technological features

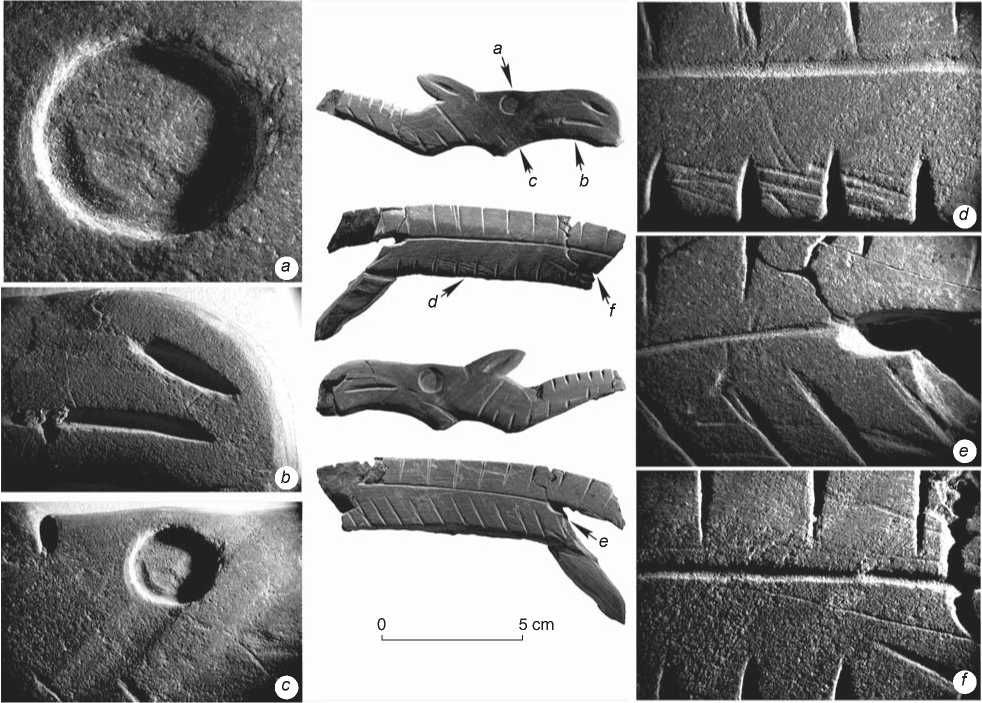

To find out whether the elk figurine found outside the graves at the Tourist-2 cemetery is contemporaneous with the rest items of portable art found in the graves, a comparative analysis of their technological features was carried out. Similar techniques of drilling, shaping the contours of figurines, and decorating with grooves by sawing, as well as intense abrasive processing (Fig. 2), occur precisely in this combination on almost all items of portable art from this site. A detailed examination of each item allows a conclusion to be drawn about the technological unity of the entire series. The closest items to the elk figurine are two anthropomorphic images made of shale and burl (see Fig. 1, 2 , 3 ). In these items, the technological similarity is especially pronounced. In this article, we will not give a detailed description of their technological characteristics; we only note that identical methods of contour design are recorded on the anthropomorphic sculptures (for example, an elk earring and the body/arms of an anthropomorphic stone figurine); all deep lines on the artifacts’ surfaces are made by sawing, the eyes of the characters are emphasized by specific drilling techniques (including circular or tubular), and the leveling and smoothing of the surface is carried out by intense abrasive processing. The elk figurine made of soft shale shows the following technological features (Fig. 3). The blank was modified using a combination of techniques: abrasion to render the general shape, and sawing grooves to shape the contour details (for

Fig. 2. Macrophotographs of details of the elk figurine. a , e , f – magnification ×12.5; b–d – magnification ×8.

5 cm

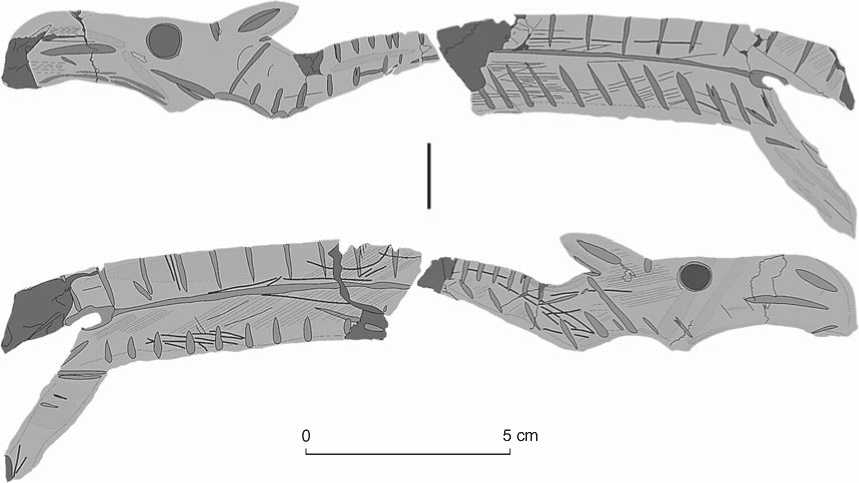

Fig. 3. Technical tracing of features of manufacturing the sculptural image of an elk.

example, at the base of the ear, the ends of grooves are clearly visible, which served to bulge this area). The same technique was applied for decoration in the form of deep notches made on both sides of the item. The grooves for shaping the contours of the figurine, in contrast to the decorative ones, could be rounded in plan view, and not only straight.

Sanding and grinding was used to flatten the surface and give a smoother shape to the already shaped areas. The entire surface shows thin linear parallel traces, mostly unidirectional (kinematics of the movements was reciprocating, not circular). There are areas where the grinding angle is slightly changed. This technique allowed the artisan to shape the facets, and thus to even “play” with volume on a flat figurine (as, for example, in the neck of the elk). There are also shallow, but relatively wide, grooves (for example, in the area of the elk’s eye, there are two parallel grooves without sharp boundaries), which were made by grinding rather than sawing. In this case, a tool with a narrow working surface was used. Additional abrasive processing of the figurine was carried out after shaping the contours of the elk image, as evidenced by long linear grinding marks on both sides, passing through the entire artifact, parallel to its edges.

The main decorative element is a deep groove, which was made using the sawing technique. In most cases, its central part is deeper and wider than the ends. This is due to the fact that during sawing, the working part is not the point, but the blade of the tool, which better works through the central part of the formed groove.

Both fragments show engraving. On one (head), there are two thin connecting lines; on the other fragment (body and hind leg), there are several lines, parallel to some grooves. This technique possibly served to mark future deeper lines. However, there is also an engraving that is not associated with grooves. These thin lines, including the curved ones, can be either part of the sketches of figurative elements, or just random ones, which is difficult to judge owing to the incomplete integrity of the item.

The elaboration of the figurine’s eyes deserves special attention. Considering the relatively large diameter, the same depth, and the flat bottom of the holes and the walls perpendicular to it, it can be concluded that these dimples could not have been simply cut with a sharpened tool. A more complex technique had to be used here, for example, circular drilling. Judging by the small irregularities at the bottom of the depression, after the formation of the rounded contour, the space inside it was scraped out.

No signs of wear were found that would allow establishing the functional purpose (or method of use) of the elk figurine. There is a slight smoothness along the contours, especially in the area of the head and muzzle of the animal, but this may be due to the final stage of the sculpture’s fashioning by smoothing the surface with a soft abrader.

The results of numerous measurements of the thickness of three-dimensional models and their subsequent comparison using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test ( U = 19; p = 0.325) unambiguously indicate that the fragments were part of the same figurштe (Kolobova et al., in press). The same raw materials and similar techniques used for decoration in both fragments also support this conclusion.

As the study of the entire series of portable art from Tourist-2 demonstrates, the main feature of making figurines (regardless of the material being processed) is the active use of two techniques: abrasion and sawing deep grooves. Of particular interest is the specific drilling method used to shape the eyes. It can be considered that the elk figurine is part of a complex of small figurines from the Tourist-2 cemetery that is completely homogeneous in terms of technological methods.

Discussion

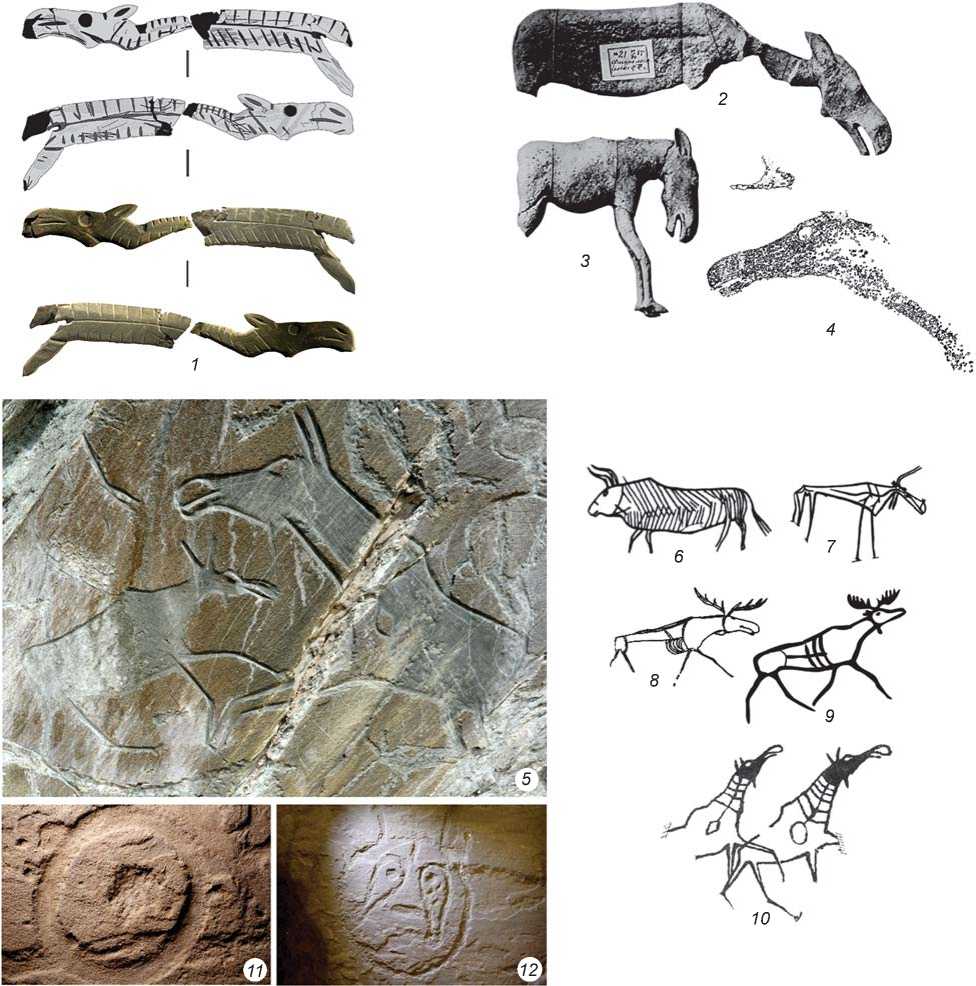

The item of portable art from Tourist-2 is an image of an elk, stylistically close to the Angara figurative tradition in the rock art of Siberia (Basova et al., 2019: 62). Despite the fact that the figurine is not complete, and it is difficult to judge the position of the animal’s body and legs, there are still reasons to attribute it to this tradition. First of all, the realism of the image of the head is noteworthy. On both sides of the figurine, the nostrils and mouth are conveyed by grooves, an earring is highlighted, and an ear is worked out in detail. The eyes are shown with even, rounded indentations. The animal’s muzzle is formed with a characteristic rounded contour (Ibid.). The image looks very realistic, detailed, but at the same time, the stylization inherent in the entire series of portable art from Tourist-2 is well traced (Fig. 4, 1 ). The unity of technological and stylistic methods of rendering the image of an elk and anthropomorphic figures makes it possible to speak of a certain pictorial canon, generally typical of the Early Bronze Age cultures in Siberia (Basova et al., 2017; Kolobova et al., 2019: 73). At the same time, the head of the figurine under consideration is exaggerated as compared to the neck and body. Notably, the figure is intact in the neck area; it is broken off only at the base. Consequently, the neck was deliberately shaped this way. The body is decorated in the so-called skeletal manner, which often occurs among the rock carvings on the territory of Siberia (Fig. 4, 1 ).

When looking for stylistic analogs, one should primarily compare artifacts of the same category and images that are identical or as close as possible in content. In this case, the image of an elk in portable art is considered. Comparison with bone items of portable art from a settlement near the village of Bazaikha (Raport…, 2013: 12, ill.), on the basis of which the

Fig. 4. Analogs among the items of portable and rock art (without scale).

1 – elk figurine from Tourist-2; 2 , 3 – bone sculptures of elk from the settlement near the village of Bazaikha (after (Raport…, 2013)); 4 – rock carving of the elk’s head at the Shalabolino rock art site; 5 – composition of two elk figures at the Tom rock art site (photo by E.A. Miklashevich); 6 – image of a bull made in a skeletal manner, Chernovaya VIII (after (Esin, 2009)); 7 – “skinny bull”, Razliv X (after (Kyzlasov, 1991)); 8–10 – images of elk: 8 – Verkhniy Askiz I, mound 1 (after (Savinov, 2006)), 9 – Ulus Sartygoi (after (Leontiev, Kapelko, Esin, 2006)), 10 – Tom rock art site (after (Okladnikov, Martynov, 1972)); 11 – fragment of an anthropomorphic mask on a stele from the Okunev mound Chernovaya XI (Martyanov Regional Museum of Local History in Minusinsk, exposition, No. A 12912; photo by L.V. Zotkina); 12 – anthropomorphic “two-beam” mask on a slab from the Tas-Khazaa mound (Kyzlasov Khakass National Museum of Local History, No. КП А ОФ 304/5; photo by L.V. Zotkina).

Angara style was distinguished (Okladnikov, 1966: 124– 125; Podolsky, 1973), allows the following conclusions to be drawn. The Bazaikha elk figurines (Fig. 4, 2, 3) are distinguished not only by their realistic performance, but also by their smooth, streamlined forms. There are no sharp lines of decoration, such as grooves. The main specificity of sculptures from Bazaikha is working with the volume of material. These features are not typical of either the flat elk figurine or most of the items of portable art from Tourist-2. Thus, in spite of the general content (the elk image), it is difficult to recognize the methods of manufacturing the figurines from these sites as similar in terms of methods of implementation (Fig. 4, 1–3). Comparison with small bone figurines of the Kitoi culture (classic specimens from the Shamanka II and Lokomotiv cemeteries) (Studzitskaya, 2011: Fig. 1, 2–9), where one of the predominant subjects is the head of an elk, allows us to draw approximately the same conclusions: streamlined, rounded shapes and a specific minimalist, naturalistic manner of execution (Ibid.: 39) are alien to the figurine in question. Of course, the difference between materials (shale and bone) should be taken into account. But among the items of portable art from Tourist-2, there are also specimens made of bone (horn, mammoth tusk); however, the methods of their processing and rendering of images are still close to a single standard, and do not radically change within the site. Nevertheless, in terms of visual characteristics, noteworthy is the design of the animal’s head: a deliberately outlined earring, a shaped nostril, and a specific rounded shape of the ear, with a depression inside, are all signs that bring the Bazaikha sculptures closer to the considered elk figurine. This similarity is due to belonging to the Angara tradition* in general, but in this case it is hardly appropriate to speak of an absolute stylistic coincidence. It is rather about different variations on the topic of the Angara motif-stylistic tradition.

Considering that the Angara style is best represented in rock art, let us turn to petroglyphs. Quite often, in the Angara images of elk, one can find a rounded eye rendered by contrerelief (Fig. 4, 4 ). Technologically, this variant differs from the smooth rounded depression on the figurine from Tourist-2. However, both methods visually emphasize the eye, which looks different as compared to the background (Fig. 4, 1 , 4 ). In general, all the details of the head and muzzle of the elk image are quite typical of the Angara tradition in a broad sense (Podolsky, 1973: 267; Sher, 1980: Fig. 101).

On the petroglyphs of the Tom rock art site, abrasion above pecking and sawing deep grooves along the contour were quite often used; such a combination of techniques was specifically popular in shaping the head and neck of elk (Fig. 4, 10). In some cases, grinding and sawing of grooves were used to fashion the entire image (Fig. 4, 5). It was these techniques that were chosen by the artisan for making the elk figurine from the Tourist-2 site. The eye in the form of a flat round depression resembles numerous items of the Okunev’s art, which show flat rounded dimples of the most varied outlines, used as elements for decorating steles (Fig. 4, 11, 12). And in general, grinding and sawing deep grooves are frequent techniques in the Okunev art tradition. The specific way of eye rendering finds parallels among the items from the Bronze Age burials of the Odino culture (for example, burial 542 at Sopka-2/4A) (Molodin, 2012: 167, fig. 230, 4).

In addition, the skeletal manner of depicting the animal’s body deserves special attention (Kovtun, 2001: Pl. 30a). This variant is found on the rocks of the Lower Tom region (images of elk) (Fig. 4, 10 ), as well as in the Okunev figurative tradition (images of elk, bull) (Fig. 4, 6–9 ).

Another characteristic feature is a deep line separating the head from the body on the elk sculpture from Tourist-2. This technique is found in some Okunev zoomorphic images and figurines of elk on the petroglyphs of the Lower Tom region (Fig. 4, 6 , 8–10 ). Such a feature of the Tourist-2 sculpture as an exaggerated head is characteristic of the Okunev art and of the petroglyphs of the Tom region (Ponomareva, 2016: 76).

All the above stylistic and technological characteristics allow us to believe that the elk figurine from the Tourist-2 settlement tends not so much to the classic Angara figurative tradition, but to its variations with increased geometrization. As has been noted more than once, the continuation of this Neolithic tradition is quite typical of the later pictorial strata, and a somewhat modified (or even strongly transformed) Angara style is used in both the Karakol and Okunev art of the Early Bronze Age (Podolsky, 1973: Fig. 8, p. 273; Savinov, 1997: 205; 2006: 160–161). Most researchers attribute elk images among the petroglyphs of the Lower Tom region to the Bronze Age, and the Angara style is considered an integral element of a kind of local geometrized stylistics: the Tom group of the “Angara” figurative tradition (after (Kovtun, 2001: 48)) or the independent Tom style (after (Ponomareva, 2016: 78)). In general, the elk figurine under consideration, from the portable art complex from the Tourist-2 site, found in a dated archaeological context, can serve as one of the reference artifacts for studying the development of the Angara style as an epochal phenomenon in Siberia, as well as the integration of Angara pictorial techniques into subsequent iconographic traditions.

Conclusions

The study has shown that two separate fragments of a small stone figurine found outside the graves of the Tourist-2 cemetery should be considered the parts of one item. The technological analysis carried out not only for the elk figurine made of shale, but also for the entire series of portable art from this site, allows us to speak about the unity of technological characteristics of the artifacts’ assemblage. Comparison of the image of elk from Tourist-2 with well-known examples of portable and rock art in Siberia leads to the conclusion that this figurine belongs to the Angara style in a broad sense, but the techniques of execution are closer to the Tom and Okunev pictorial style. This is quite consistent with the preliminary date obtained for the Tourist-2 cemetery, which makes it possible to attribute it to the Early Bronze Age. However, it should be emphasized that it does not give a complete idea of the age of the site. It requires a series of dates to refine it.

Thus, the sculptural image of elk from Tourist-2 can be considered one of the reference artifacts that chronologically and stylistically mark the development of the Angara tradition. It is especially important that this figurine was not only found in a dated archaeological context, presumably in a destroyed burial, but is also a component of a whole series of portable art, homogeneous in terms of iconography and technological methods of execution, characteristic of the Karakol-Okunev art or, more precisely, “Krokhalevka” style.

Acknowledgement

This study was performed under the Public Contract No. 03292019-0003 “Historical and Cultural Processes in Siberia and Adjacent Territories”.