An old Turkic statue at Borili, Ulytau hills, Central Kazakhstan: cultural realia

Автор: Ermolenko L.N., Soloviev A.I., Kurmankulov Z.K.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.44, 2016 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145278

IDR: 145145278 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0102.2016.44.4.102-113

Текст обзорной статьи An old Turkic statue at Borili, Ulytau hills, Central Kazakhstan: cultural realia

The nomadic lifestyle is usually associated with extensive animal husbandry, and in the Eurasian Arctic, with reindeer-herding. But pastoralism is not equivalent to nomadism. Not only nomadic hordes and shepherds, but also migratory hunters and warriors, traveling salesmen, craftsmen, artists, and healers were all nomads. Today, they are joined by “neonomads”: mobile businessmen, people engaged in transportation and cyber-networks, real and virtual travelers of all kinds.

There is a widespread delusion that nomadism emerged either in the Neolithic, with the advent of agriculture, or in the Mesolithic, through the development of hunting strategy. But in fact, nomadism is a primordial and original state of mankind that made possible its spread throughout the globe. Nomadism is not an “episode” but rather a long-standing phenomenon. There are at least three thematic and chronological “horizons” in studying nomadism: (1) nomadism as an aspect of culture from the most ancient times; (2) the place of nomads in history; (3) nomadic algorithms in modern mobility technologies. In other words, the aim of nomadology is to study not only particular nomadic communities but also the phenomenon of movement in anthropology and history.

The Arctic is a space where the nomadic tradition still persists strongly. Reindeer-herders (Saami, Nenets, Evenks, Evens, Chukchi, Koryaks), dog-breeders (Eskimo, Yukaghirs), seafarers (Normans, Pomors, Eskimo), horse-breeders (Scandinavians, Russians, Yakuts), foot-sloggers (for instance, in Chukotka, running and fast-walking were nearly objects of a cult) were nomadic in the high latitudes of Eurasia at different times. These mobile cultures were interacting in contact areas: seafarers, reindeer-herders, horse-breeders, and dog-breeders made up a communication network that produced a “circumpolar culture” effect.

Mobility is a key feature of inhabitants of high latitudes, an algorithm of their culture where dynamics dominates over statics. In many Arctic cultures, nomadism was considered wellbeing, and settled life a misfortune. Mastery and control of vast territories have largely shaped the motivation and philosophy of life of hyperboreans. It is not just a metaphor that not small nations, but rather cultures of vast area have always existed in the North. The aim of this article is to define the field of activity of a Northern nomad, who is commonly viewed as a primitive shepherd monotonously watching over his herd.

Field methods of the anthropology of movement

The method of movement-recording, termed TMA (tracking–mapping–acting), is particularly suitable for studying nomadic technologies. It includes three types of documentation: (a) GPS-tracking of movements of a person during a day; (b) mapping the locations of nomads’ camps during a year; (c) photo- and video-recording of actions. The GPS movement-tracking, accompanied by a visual background, can vividly convey the “anatomy of mobility”. This is a kind of animation of the activityfield that reveals a multidimensional pattern of nomadic movement with peaks and pauses, personal and social trajectories (Golovnev, 2014).

A day-route track on the map is supplemented by the following information: (1) main activity during the day, (2) rhythm and episodes of action, including pauses, (3) tools and equipment, (4) interaction with partners, (5) task-execution and own decisions, (6) terrain, and (7) weather. The actions are fixed via photo- and video-recording, whereby all episodes should be imaged. However, the fullness of such recording depends on the situation and external (e.g. weather), as well as internal (e.g. nomad’s mood), circumstances. Ideally, a synchronous tracking of all inhabitants of the camp provides a full picture of the movement/activity of a nomadic group, which permits definition of the general rhythm and the intense episodes of activity, communication nodes, and the role of a leader.

The mapping makes it possible to consider the system of movement at different scales: from a scheme of annual migrations (general view) to the maps of seasonal movement (medium view), and, finally, to the topography of single camps and pastures (close view). The general view shows not only the route of a nomad, but also his contacts with semi-settled trade populations or settled township people. Identification of the mobility pattern of different groups and the type of their contacts (cooperation, competition, conflicts) is crucial for understanding the mobility strategy and motivation.

It is necessary not only to observe the nomadic mobility, but also to take part in it, particularly in critical episodes. Nomads usually look kindly on ethnographic studies of their movement; and, realizing their advantage in mobility, they are keen to share their skills with the researchers.

According to the aims of this study, I present here just a small sample of the collected TMA data: the patterns of activity of three leaders of nomadic groups from the Chukotka, Yamal, and Kola peninsulas, describing them from the East to the West—as the sun goes.

Three tundras

The Chukotka, Yamal, and Kola peninsulas, having a lot in common, but nevertheless display substantial differences in the herding styles and mobility of the Chukchi, Nenets, Saami, and the Izhma-Komi. In each of the tundras, reindeer-herding developed independently, on the basis of local hunting traditions; although the circumpolar contacts have always provided for the exchange of nomadic technologies (e.g. during the expansions of Ymyyakhtakh culture, “stone” Samoyedic peoples, “stone” Chukchi, and the Izhma-Komi).

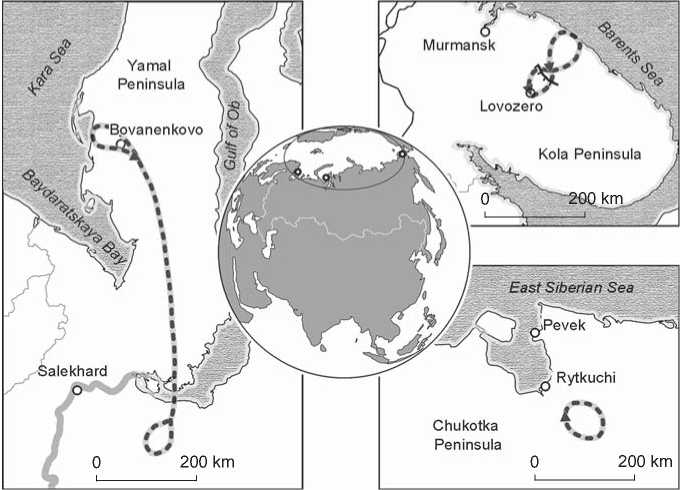

Unmounted and harnessed grazing of large herds is typical of the mountain and costal tundras of Chukotka. In the 20th century, it was supplemented with cross-country vehicles. Here, the horizontal (tundra-sea) and vertical (mountain-valley) migrations are combined. In summer, winds of coastal and mountain tundras give protection from biting flies, while in winter, lowlands and valleys covered with forest provide fuel and protection from cold winds. The annual migratory cycle of herders is circular (Fig. 1), and the pastures of Chukotka are divided into “nomadic circles” belonging to different brigades. The area of such a circle is approximately 5–6 thousand km2, with a radius of 40–60 km. A herder, moving on foot or on a reindeer sled, is able to cross it in any direction in one or two days (the Chukchi consider a walk of 40 km per day to be average for a man). Thus, the whole circle is under control of the nomad. Such cyclic localization of the pastures enables reindeer to graze freely, only occasionally controlled. The herd is gathered together in autumn.

Fig. 1. Migrations of reindeer-herders of Yamal (4th brigade), Kola Peninsula (“left wing”), Chukotka (3rd brigade) (shown by dotted line).

The vast lowland tundra of Yamal, spanning 700 km from forest to seaside, sets a seasonal pace for meridional migrations of reindeer-herders. The migrations are up to 1500 km in length, and large herds are watched over perennially using reindeer-sleds pulled by special dogs. Such large-scale migrations are stimulated by the need for firewood, protection from winds in winter, and the search for northern coastal pastures in summer when the rest of tundra is covered with swarms of mosquitoes and gadflies (a comfortable summer tundra is called a “herder’s paradise”). The migrations between summer and winter pastures go through the “Yamal ridge” (Khoy), an elevated watershed between the Baydaratskaya and Ob flows (Fig. 1). In spring and autumn, it is almost completely covered with reindeer herds moving to summer or winter pastures (the main flow via the ridge makes more than a half of the total migration). Northern and southern phases of annual migration are greatly divided by this mainline: the Nenets traditionally consider summer ( soon ) and winter ( tal ) to be two different years.

The Kola tundra looks like a narrow strip (about 100 km wide) between forest and sea. Here, the Saami have long practiced the grazing of small herds (up to several dozen reindeer) with short migrations; for transportation they used sleigh (kerezhki) and pack saddle. This so-called “cottage herding” comprised the milking of does, free summer grazing, and gathering of herds using herding-dogs. In the 1880s, the migrant Izhma-Komi introduced to the peninsula commercial breeding of large herds with perennial grazing, large-scale autumn slaughtering of reindeer, hiring of shepherd-workers (including Saami), and commercial manufacture of various goods (e.g. suede or fur clothes). In the 1970s, the Kola reindeer-herders got back to free summer grazing (Fig. 1), and a solid fence (ogorod) was built at the border between tundra and forest,, in order to control seasonal migrations of the reindeer. Along the fence, cottages and wooden corrals were built. The herding became “cottage”, and “nomadizing” became rotational, with people going away for shifts and later returning to settlements (Lovozero, Krasnoshchelye). As a herder V.K. Filippov from Lovozero says, comparing Kola and Yamal traditions, “In the big [Yamal] tundra, fences do not make sense; the routes are narrow, about a thousand kilometers each. Let the herd go, as we do, and it will mix with the neighboring herd, and will be eaten. But here it is comfortable for us, particularly with such a small number of herders”.

The social adaptation of reindeer-herders is no less important than the ecological. The 16th–18th centuries were the time of a “reindeer-herding revolution”, which rolled from the West to the East of the Eurasian tundras as a response to Scandinavian and Russian colonization of the North. The mass migrations of the northern nomads were accompanied by strife for reindeer herds and by settling in the most remote tundras. Even today, the success of herding depends not only on the availability of pastures but on human resources as well. The three Eurasian tundras are almost equal in terms of their herding potential: in Chukotka, Yamal, and Fennoscandia (including the Scandinavian and Kola tundras), the population of domestic reindeer approximates 500 thousand head. The reaction of the reindeer-herding societies to social change is particularly evident when comparing Yamal and Chukotka, the world leaders of reindeer-herding in Soviet era. In 1990, the numbers of reindeer in the Yamal-Nenets and Chukotka autonomous okrugs were equal: 490 and 491 thousand head, respectively. But the post-Soviet crisis had different effects in Yamal and Chukotka: by 1995, the reindeer population of the Nenets has grown to 508 thousand, while that in Chukotka had decreased to 236 thousand head. Today, there are about 600 thousand domestic reindeer in Yamal and about 200 in Chukotka (in total, there are ca 1.8 million domestic reindeer in the world). Each tundra suffers from its own crisis: in Yamal there is an overproduction of reindeer, while in Chukotka there is a catastrophic fall of production. The stability of herding in Yamal and vulnerability in that in Chukotka largely depend on the sociocultural situation in both regions: persistence of private herds in Yamal and their total collectivization in Chukotka. Furthermore, the decrease in the reindeer population in Chukotka coincided, both in terms of scale and time, with a massive (up to 2/3) post-Soviet departure of nonnative people, mainly qualified specialists. In contrast, the social and demographic structure of the Yamal population was preserved. Following a formerly popular logic of the conflict of interests between indigenous population and newcomers, it might be expected that the leaving of the latter would open new avenues for the

Yarangas

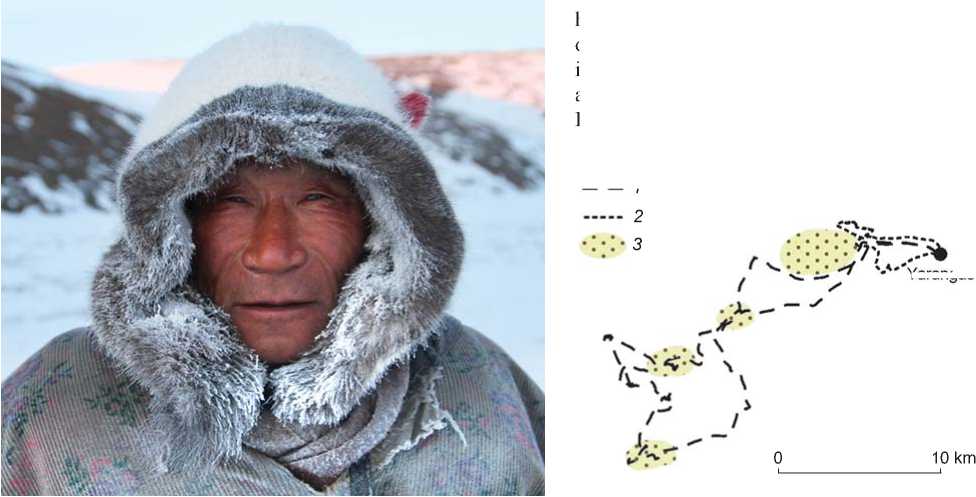

Fig. 2. Andrei Fedotovich Antylin, aged 73. Mentor of the 3rd reindeerherding brigade of the “Chaunskoye” agricultural enterprise. Nick name: the Elder.

traditional economy, particularly for reindeer-herding, demanding a space for pastures. But in fact we see the opposite situation: the crush of the social environment, which Chukotka’s culture has been adapting to for decades, has plunged the region into a systemic crisis, an ambience of chaos and marauding. Yamal has become the sole leader in world reindeer-herding, three times surpassing Chukotka.

Our results confirm the idea that human (and ethnocultural) potential is the main driver of reindeerherding and nomadism. Three centers of reindeerherding in the three tundras were chosen for observation: the Chaun tundra of Chukotka (ca 100 herders and 22 thousand reindeer), the northwestern tundra of Yamal lying between Kharasavey and Mordy-Yakha (ca 90 herders and 23 thousand reindeer), and the Lovozero tundra of the Kola Peninsula (ca 50 herders and 25 thousand reindeer). In all three tundras, key roles belong to influential leaders whose experience and energy (according to the local people’s belief) are the backbone of reindeer-herding. Thus, their activity patterns are of principal interest for studying modern Arctic nomadism.

Andrei Antylin (Chukotka Peninsula) had many times to start from scratch and raise a herd (Fig. 2, 3). Fifteen years ago, he was persuaded to leave the successful 3rd brigade with 6 thousand reindeer, and to lead the distressed 1st brigade. Over five years (1999–2004), he managed to increase the number of reindeer from 800 to 5 thousand head. Meanwhile, the herd of the 3rd brigade has almost disappeared. Asked by his elder brother Vukvukay, Andrei went back and restored the herd to 6 thousand head. Only 3 out of 12 brigades of the Chaun tundra exist today; among them, one is led by Vukvukay (12 thousand reindeer) and another, by Andrei Antylin (6 thousand reindeer). Both brothers are strong enough, despite their

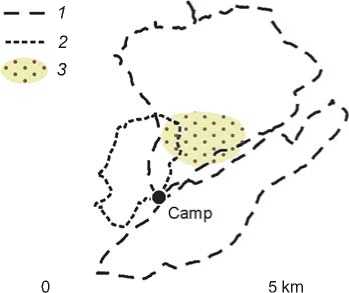

Fig. 3. Tracks of the mentor ( 1 ) and the shepherd ( 2 ) (Chukotka).

-

1 – Andrei Antylin, cross-country vehicle, 90 km;

-

2 – Grygory Pavlyukov, unmounted, 26 km; 3 – reindeer.

venerable age: Vukvukay still wins races, although over 80. Having formally passed foremanship to their sons and being just mentors today, both actually still rule their brigades. The Chukchi consider them the leading herders of the Chaun tundra.

In Vukvukay’s camp, the old customs dominate and the old rites are performed; while in his brother’s camp, the sacred dolls taynykut are left in only one yaranga. Andrei Antylin was the first in the Chaun tundra to drive a “Buran”, buy a computer, and master a quad bike. Vukvukay relies upon the old, and Andrei is brave in admitting the novelty; in the Vukvukay’s camp, the Chukchi language is spoken, and in the camp of his brother, mostly Russian. At his own risk, he mixes the Chukchi customs and new technologies.

Like many herders in Chukotka, Andrei Antylin has a “reindeer thinking”, which is reflected, for example, in the names of months: gro-jyligyn— calving (April), netgyligyn —the skin peels from horns (August), ejnejgylgyn— rut (September), chachal-jilgyn— hair on the snouts of fawns in the womb (February), l’orgyka-jilgyn— the head with hair of the fawns in the womb (March). Antylin characterizes people as if they were reindeer: “mushrooms-eater”—a lover of mushrooms (pleasures), who forgets everything for this; “urine-eater”—a person who likes human urine, who easily lets other people to take control of him (a definition of submissive people). He has strictly scolded a young herder who hit a reindeer and gouged out its eye. But when an aggressive reindeer, tied up behind his sled, was butting him, Antylin did not lash it, but instead reasoned with the reindeer: “Why are you butting me, after all, I cannot butt you, I do not have horns”. His perception of weather is also related to the care of reindeer: if it is warm, there will be gadflies whom reindeer dread more than wolves; if there is fog, reindeer will scatter and may be killed by wolves. The state of the does before calving attracts Antylin’s greatest sympathy: “The fetus is moving inside the doe, and so the doe moves fast”. Having noticed the crows, he says, “These now imagine how they will be pecking the fawn’s eyes”.

Wild reindeer (“savages”) are perceived by Andrei Antylin from the point of view of the keeper of the herd. He points out such merits in “metis” (offspring of wild and domestic reindeer) as strength, beauty, ease of running, and the ability to lead the herd through good pastures. That is why he does not drive a stray wild male away from the domestic herd: “Let him walk, he is going to produce good reindeers for us”. Antylin keeps an ancient Chukchi custom noted by V.G. Bogoraz (1991: 10–11) long ago: herders attract the savages to the herd and value their offspring for quickness in the sled team, and for their ability to attract wild reindeer during hunting. But he knows very well that when rut begins, the savages can split domestic herds and lure away its parts (in 2008, the savages lured away the whole herd of the 1st brigade). Domestic reindeer easily succumb to the beautiful savages, follow them, and do not obey the herders. Thus, the savages become a threat for Antylin in the time of gathering the herd in autumn: “The savage must be killed, so he does not muddle the herd”; “wild must be wild, and reindeers must be in the herd”. According to Antylin, people today have gotten weaker, and wild reindeer have gotten stronger, “Masters have died out, and the savages have thrived”.

The gathering of the breakaway parts of the herd in late summer is a complicated set of actions by a search team comprising a cross-country vehicle and herders, some of whom (herders-keepers) watch over the main herd, while others (herders-searchers) drive the breakaway parts to the herd. The work is complicated by movements of the main herd, which can at any time break apart owing to fog, wolf- or bear-attacks, or inefficient guarding; or because of the interest of the reindeer in mushrooms. The parts grazing on mountainslopes have to be “pushed” from different sides and with a certain amount of effort towards a convenient valley so that it will be possible to gather them later with one maneuver on a cross-country vehicle.

The parts of the herd led by the savages are particularly difficult to control. As a cross-country vehicle is following a part running away, its appearance and roaring make the savages shoot ahead, while domestic reindeer lag behind. At this moment, it is necessary to drive a wedge between the wild and domestic animals, and divide them by shouts and frightening gestures. If this doesn’t succeed, then a carbine comes to play, and the savage falls victim to his own beauty and strength.

The gathering of the parts of the herd is reminiscent of military activities in terms of exertion. Andrei Antylin controls the whole chain of these parallel and sequential actions designed to push the herd to yarangas, join the parts, and assign other herders to be the keepers, the searchers, and the drivers. He also controls the movement of the cross-country vehicle, the quad bike, and the savages—as well as the camp life with its women’s affairs. All the participants of the race follow his directives blindly, and he is the Elder who makes the herders act as a team. The finale of this long and versatile activity is the einetkun— “young reindeer’s fest”, which is not bound to any particular date but is celebrated upon the successful gathering of reindeer. The einetkun is a kind of “victory day” for herders.

Besides herding, Antylin controls the “social front” where he struggles with alcohol sellers (who are poachers as well) and with the recently appointed Director of “Chaunskoye” agricultural enterprise. The alcohol sellers are the worst enemies of the Elder: they “have killed the elder son”, “have finished the nephew”, and they “are getting to Ivan [the younger son]”. Antylin does not like fests, and he is afraid of the guests from the village. He believes that the vices of settled life kill the tundra youth and take away the future of the Chukchi. In September 2013, the Elder found the alcohol-sellers at his brigade and alone entered into an unequal battle, shot out the tires of their car with his carbine, and called the police by a satellite phone. But the police officers gave their own interpretation to Antylin’s actions when he caught the sellers in the act: they confiscated the Elder’s carbine and charged him with “intentional damage to property… in a socially dangerous way”. The investigation has lasted for 1.5 years, and many of Antylin’s tribesmen did not share his tenacity in the struggle with the “mafia”. Only in April 2015 was his carbine returned to him, and the case seemingly closed.

The conflict between Antylin and the Director of “Chaunskoye” agricultural enterprise has lasted for two years (as of the end of 2015). If Antylin is talking about somebody but does not mention his name—does not even use a pronoun—that means he is talking about the Director, who annoys him no less than the savages and poachers. The Elder realizes that the Director is supported by a mighty corporation, and it is a big risk to be at odds with it. But Antylin is inexorable: he feels responsible for the fate of the Chukchi (both nomadic and settled). And so, he insists that the enterprise move back from Pevek city to Rytkuchi village, and

Fig. 4. Nyadma Nyudelevich Khudi, aged 56. Brigade-leader of the 4th brigade of the “Yarsalinskoye” reindeer-herding enterprise, the honorary reindeer-herder of Yamal (since 2011). Nickname: Tartsavey (the Beard).

he claims attention and respect for the herders. The competition with the Director additionally mobilizes Antylin. The 73-year-old Elder controls the space of tundra surrounded by a complicated network of natural and social factors: from seasonal migrations and watching over reindeer to saving his tribesmen from the poachers, alcohol-sellers, and harmful (from his point of view) managers.

Nyadma Khudi (Yamal Peninsula) confesses the Nenets creed: the reindeer-herder feels good if his reindeer feel good (Fig. 4, 5). Like Antylin, he has a “reindeer sense”: watching around a pasture during migration, he says gladly how good reindeer “will be eating” here. Sometimes, Nyadma sincerely condoles: “Reindeer cry when they feel bad, when they are beaten, when they are castrated inappropriately”. He perfectly understands what hardships fall on reindeer in hot weather, when they are overwhelmed by mosquitoes and gadflies, when the thread of “foot rot” (necrobacillosis) and “cough” (cephenomyosis) infections is rising. Having noticed the disease, a brigade-leader immediately drives the sick animals to the tail of the herd, or sends the “sick part” to a separate pasture with a shepherd. The brigade-leader watches not only over the herd, but also over the neighborhood in order to decide what to do next. That is why his track is longer than a track of a common shepherd.

The skill of the reindeer-herding Nenets is in maneuvering with the herd in a “sea of reindeer”. The navigation between numerous herds— especially in the stream of mass migration through the ridge of Yamal—requires being able to avoid encounters with other herds, but at the same time not lagging behind them (a latecomer goes through devastated pastures). But successful maneuvers would be impossible without the support of kin and the goodwill of the neighbors. In family and

Fig. 5. Tracks of the brigade-leader ( 1 ) and the shepherd ( 2 ) (Yamal).

1 – Nyadma Khudi, reindeer sled, 31 km; 2 – Alexandr Khudi, reindeer sled, 12 km; 3 – reindeer.

between-kin relationships, the herder must be as skilled as in using lasso or ruling a reindeer-sled.

As the herders say, the tundra migrations resemble a game of chess. This similarity is further strengthened by the traffic rule of the Nenets: “We nomadize checkerwise so as not to mix reindeer”. Each “player” leads his argish (caravan) via the ridge of Yamal, trying to leave neighbors behind and be the first at the best pasture. But always moving ahead of the curve is not allowed; thus, the nomadic leader sometimes surrenders the initiative to a neighbor so as to have a reason to make a crucially important move to outrun at the right time (for instance, at the entrance to calving pastures). The tradition says that herds of different brigades shall alternate with each other in the vanguard.

The routes of herders over the land are depicted on maps as lines; but in fact they more resemble a lacework. According to the track records of Yamal reindeerherders, they graze the herd in a 5 km circle around their camp, driving reindeer round this circle from section to section following the sun. Then, the brigade moves to another place, some 10 km from the previous one, and repeats the circular grazing. The line depicting the movement of the herd in such a sequence resembles the petals of a flower. However, any herd may encounter another herd circling in the same way, which can have fatal consequences, up to the complete loss of reindeer. This occurs mostly because of fog, but also as a result of a blizzard, an ice-slick, a wolf-attack, or a mistake on the part of the shepherd.

For the Nenets, the authority of a herder depends entirely on his skill in “herd navigation”, and the words erv (chief) and teta (having a lot of reindeer) are almost synonymous. The reindeer herd is not only the basis of subsistence, but also a tool of spatial strategy; that is, in a nomadic tactic, “pressure of a big herd”. A herd of many thousands of reindeer is the main figure on the nomadic “chessboard”. It moves faster than smaller herds, and its “flywheel” covers huge territories. If a big herd “covers” reindeer of a small sluggish herder, this latter will have either to laboriously catch his reindeer in the huge herd of his neighbor (which is impossible on his own), or to follow it submissively. Sometimes the return of the lost reindeer occurs only at the winter corral (a control paddock used for counting and sorting of herds) in the southern tundra. Not every small herder is able to take this chance, as he moves substantially slower than a big herder or a brigade. If the small herder cannot catch his reindeer before winter, then, by the law of tundra, they can be used by their new owner at his own discretion (Golovnev et al., 2014: 32–50).

In August 2013, a part of the herd of a private herder Petr Serotetto (nicknamed Tarzan) mixed with the five-thousand-herd of the 4th brigade. The brigade-leader Nyadma found before himself a tough choice. On the one hand, it was an opportunity to give a good lesson to an intrusive neighbor; but on the other hand, Nyadma knew that Serotetto was famous for his independent character and an astounding (even supernatural according to gossip) luck in herding: during four years, his herd had increased from 70 to 800 heads; “all his youths live, and one-year old does spawn”. He grazed his reindeer with just one chum, maneuvering among numerous herds. This inspired the respect of some and the sympathy of others. Finally, Serotetto belonged to one of the most numerous clans of the western Yamal. There is a rule in the Nenets tradition for family-neighbor relationships: your attitude towards others is the same as their attitude towards you. So, the brigade-leader had taken a decision, complying with the tundra ethics: the whole brigade was helping Tarzan to catch his reindeer.

The 4th brigade resembles an extended family, in which Nyadma is not only a herding-leader, but also a father and an elder brother to most men. He always leads the caravan, and he is the first to place his chum at the camp. His younger brother Evgeny closes the caravan and the row of chums from the opposite side. Decisions are made in the same manner: the brigade-leader starts a discussion, his brother supports him, and then the brigadeleader takes the final decision. Such a patriarchal style of leadership is still the norm for the nomadic Nenets. Using kin relationships, Nyadma also influences the neighboring 8th brigade, where his mother lives. She plays a role of a “grand mother” ( narka nebya ) for the members of both brigades.

The difficulties of nomadic life are further worsened by the expansion of the oil and gas industry. The route of the 4th brigade has been blocked by a huge industrial base of the Bovanenkovo oil and gas condensate field. Several years ago Nyadma had to decide: should he give up reindeer-herding, or keep on working taking into account the “Bovanenkovo factor”, as there is no other route to coastal pastures. And he dared the risky experiment of running reindeer through the industrial “jungle”: for three days, the herders had to drive five thousand reindeer through a narrow corridor, which was marked on concrete roads by traffic signs “Reindeer”. They faced a lot of troubles, including crossing the roadway, moving under pipelines, and lodging for the night by arrangement with chums among industrial structures. Today, this compelled innovation becomes a tradition: migrating over the area of commercial development of the Bovanenkovo field has turned to a show performed by the 4th and 8th brigades twice a summer. The herders, reindeer, workers of the industrial base, and guests that include TV crews from various countries—all take part in the show. The herders, demonstrating a masterful control of the herd, find a kind of drive of extreme experience in front of hundreds of spectators in this “polar encierro” (the Spanish tradition of running of the bulls through the city streets). It seems that now the Nyadma’s title “honorary reindeer-herder of Yamal” implies some new competencies.

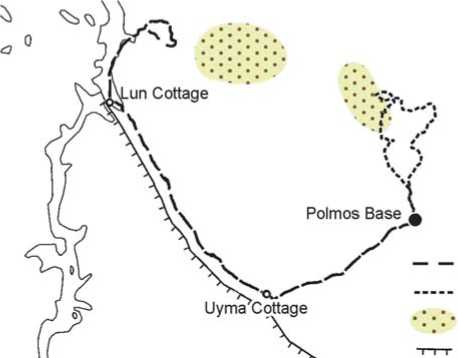

Vladimir Filippov (Kola Peninsula) is not as immersed in the “reindeer thinking” as his colleagues from Chukotka and Yamal (Fig. 6, 7). For him, reindeer are just an object

Fig. 6. Vladimir Konstantinovich Filippov, aged 55. The Head of the reindeer-herding plant of the “Tundra” agricultural enterprise (Lovozero). Komi-Ukrainian by birth. Nickname: Waldemar.

0 20 km

Fig. 7. Tracks of the head of the plant ( 1 ) and of the shepherd ( 2 ) (Kola Peninsula).

1 – Vladimir Filippov, snowmobile, 116 km; 2 – Andrei Sorvanov, snowmobile, 39 km; 3 – reindeer; 4 – fence.

of commercial production. He follows in the footsteps of his ancestors, the Izhma-Komi, who were able in the 19th century to create something unbelievable: “reindeerherding capitalism”, with hired tundra proletarians, the cycle of processing and selling the products (including the Zyryan suede), and perception of reindeer as a capital asset. As a result of the expansion of this “economic miracle of tundra”, the Izhma-Komi reached the Kola Peninsula in 1880s.

Since his youth, Filippov has been a witness and participant of the renaissance of “tundra capitalism” and the subsequent “snowmobile revolution” (stimulated by the proximity of the industrial zone) from 1980 to the 1990s. Today, he plays the role of a captain of the reindeer business (see Fig. 6). Being the head of the reindeer plant of the whole cooperative and, at the same time, the chief of its “left wing” (which includes three brigades with a total of 7–8 thousand reindeer), he connects, by his control, the Lovozero settlement with the Polmos corral base, and the reindeer-herding brigades. He personally keeps count of reindeer at the corral, and coordinates the interaction between the left and the right wings (the latter also includes three brigades). He is aware of everything related to the shepherds, herds, equipment, fuel, and complex of buildings and structures. His frequent and unexpected visits create the effect of an all-seeing eye. Filippov does not graze reindeer himself, but he leads the shepherds.

The head of the reindeer plant is responsible for the whole reindeer-herding cycle, which includes spring calving, summer feeding, autumn gathering, December corral, wintering, and, finally, selling the products. The corral is the center of the Kola reindeer-herding today: the place and time of examination, sorting, and utilization of the herd. By December, reindeer are directed to the Polmos corral where calculations are made, the animalyield is distributed, and a “slaughter part” is identified. The latter is driven to Lovozero, to the slaughterhouse, and includes handsome white reindeer which are sold to “Fathers Christmas” before the New Year. The rest of the herd is sent to wintering grounds (December to March). By the end of wintering, the animals are driven to the corral again, where the bulls are castrated, and the pregnant does are aggregated in a separate herd ( nyalovka ). In June, a “light corral” ( tandara ) is made up, where reindeer are branded. Then they let the whole herd, excluding rideable bulls, go for grazing to the coastal tundras.

The reindeer-herding production implies a strict discipline and division of workers into several groups: brigade-leaders, “seamen” (experienced herders who gather reindeer in the rocky coastal tundra), common shepherds, “gardeners” (those who “sit” in cottages and look over a 10 km sector of the fence), “chum workwomen”, and corral workers. These temporary groups are formed by the head of the “left wing”.

Each group has its own mobility pattern: the track of a “gardener” is short and monotonous, the track of a “seaman” intricate and variable.

Not long ago, shepherds with loaded bulls went in summer to the seaside to fish and watch over the herd. Today, such summer trips are less usual, and are made without rideable reindeer. Near the sea, the herders stay overnight at the recently established hostels.

The important changes in reindeer-herding and mobility were brought about by the “snowmobile revolution” (Istomin, 2015). In the Kola Peninsula, the snowmobiles have replaced the Izhma sleds, Saami packs, and herding dogs, and have become the main helper in watching over the reindeer. Only in May, and just for one month, the shepherds change to sleds; but soon a quad bike may supersede the reindeer sleds (now, only Filippov drives a quad bike). This equipment has made it possible to halve the number of people in brigades, and replace the permanent pasturing of the herds by periodic watch-keeping. All these innovations alienate the shepherd from the herd, and for him the nomad camp is not associated with home anymore. Today the herder is much like a rotational worker who visits the herd for a couple of weeks. The herders’ children know reindeer mostly as venison.

Filippov is interested in personnel for herding. He believes that the herder is motivated not by a regular salary (ca 15–20 thousand rubles per month), but rather by the income from slaughtering his private livestock. The head of the reindeer plant controls its replenishment by distributing the animal yield at the corral. According to the existing standard, a shepherd can have up to a hundred private reindeer, grazing together with the main herd, and he takes a half of their litter. The shepherd’s profession remains ancestral: a family tradition and a vocation. According to Filippov, “there must be domesticity, there must be private reindeer, there must be a connection with the herd; no connection—no work”.

He is particularly concerned with poachers (who are also called “bracks”). In 1990s, it was common to see the following scene: a killed reindeer is pulled on one horn by a shepherd, and on another by a “brack”, and they are arguing about whom the reindeer actually belongs to. The pastures remote from Lovozero (between Murmansk and Tumanny) were lost for herding because of an invasion of “bracks”. The turning-point was reached 15 years ago, when a special forces troop called “Rys” helped the herders. In the winter tundra, a team of soldiers and herders on six snowmobiles captured three bands of “bracks” in the act. After this raid by “Rys”, and for the next five years, the “bracks” had a dread of herders. The herders began to wear black masks, so that the “bracks” thought that they were being pursued by the special forces troop again. “This is the only way to stop bracks, and fines are just bullshit”, Filippov says.

Filippov bravely moves towards modernization and centralization of reindeer-herding. Earlier, each brigade of the “left wing” grazed its own herd, and had its own base and corral. Filippov has merged the herds of three brigades into one, transformed their bases into transit guest cottages (stops), and turned the corral at Polmos into a paddock complex of high throughput capacity. A settlement with houses for the brigades and their guests, canteens, bath-house, toilets, LED-lightning, and a wind farm is rapidly growing nearby the corral. People call this settlement Filippovka.

Filippov is a herder-businessman. Supported by his three adult sons, he controls all the reindeer-herding of Lovozero; and even the Director of the “Tundra” agricultural enterprise does not interfere with his activities. Sometimes, his carefulness seems excessive: for instance, being a zealous advocate of cleanliness, he picks up garbage near the houses himself. The reindeer plant headed by him is the only profitable plant in the “Tundra” cooperative.

Conclusions

Where do people with a strategic talent appear from in the tundra? On the one hand, this is the influence of the northern tradition, affirming people to be the rulers of their own fate; on the other hand, the strategic talents develop together with the responsibility taken on by the leaders. However, the leaders described above are not lonely heroes: their power is supported by the strong kin relationships without which nomadic strategies do not work.

One of the basic values of the nomads is independence. The Chukchi, Nenets, and Saami graze reindeer in different ways, but they all consider reindeer-herding the kernel of their economy, and reindeer a symbol of their independence (for the Izhma-Komi it is a commercial project as well). The herding makes them independent in terms of transport, economy, social life, and worldview. And this independence, in turn, creates conditions for the distinctiveness of any culture relying on nomadic reindeer-herding as a subsistence strategy.

The spatial technologies of Eurasian Arctic are diverse: the “circular” style of the spatial control is typical of Chukotka, “migratory” of Yamal, and “fenced” of Kola. But all these practices are complex sets of actions directed by herding leaders. The leaders believe that herding is impossible without authoritarian control.

The spatial control has two dimensions: natural and social. The former includes control over territory and reindeer; the latter, control over the nomadic community, external contacts, and conflicts.

The three examples (Chukotka, Yamal, and Kola) are illustrative in terms of their adaptability. Relying upon traditions, the nomadic leaders are nevertheless open to innovations, which expands the range of their activities and responsibility. The balance between traditions and innovations, which is regulated by the leaders, is of crucial importance in the context of the “technological revolution”.

Mobility, including nomadism, has always been and still is the basic principle of development of the Russian Arctic. The topic of the contrast between the values of nomadism and sedentariness, nomadic camps and settlements, is pivotal for the Arctic. Many of technological innovations, particularly those related to transportation and navigation, do not destroy but rather develop the nomadic culture. And many traditional technologies of the life-in-motion can be seen as valuable resources for the development of present-day Arctic strategies.