An Old Turkic statue from Borili, Ulytau hills, Central Kazakhstan: issues in interpretation

Автор: Ermolenko L.N., Soloviev A.I., Kurmankulov Zh. K.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

We describe an unusual Old Turkic statue at Borili (Ulytau, Central Kazakhstan), distinguished by a peculiar position of hands and by an unusual object-a pickaxe held instead of a vessel. Stylistic features and possible prototypes among actual pickaxes suggest that the statue dates to 7th to early 8th centuries AD. The composition attests to the sculptor's familiarity with Sogdian/Iranian art and with that of China. Several interpretations of the statue are possible. The standard version regarding Old Turkic statues erected near stone enclosures is that they represent divine chiefs-patrons of the respective group. Certain details carved on the statue indicate an early origin of the image. It is also possible that such statues are semantically similar to those of guardians placed along the 'path of the spirits" near tombs of Chinese royal elite members.

Old turks, statues, central kazakhstan, sogdian art, china, path of the spirits, bladed weapons

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146030

IDR: 145146030 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2018.46.1.059-065

Текст научной статьи An Old Turkic statue from Borili, Ulytau hills, Central Kazakhstan: issues in interpretation

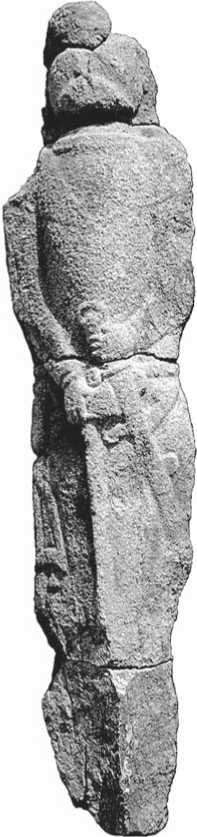

A stone statue that was recently discovered from the location of Borili, in the Ulytau Hills, southwestern Kazakh Uplands (Saryarka), was described earlier (Ermolenko, Soloviev, Kurmankulov, 2016). This fulllength statue of a man leaning on a battle axe with one hand and holding the handle of a straight-bladed weapon in a sheath attached to his belt was found broken into several parts. On the statue, there can be clearly seen lapels of clothing, bracelets, a torque, earrings, belt with onlays, a short-bladed weapon with a handle located at an angle to the blade and equipped with a ring-shaped pommel, round and rectangular handbags with pendants, and a whetstone (Fig. 1). Although this sculpture undoubtedly belongs to the Old Turkic world, a number of parallels point in the Sogdian-Iranian direction. Yet, in the search for explanation of the worldview and visual phenomenon behind this image, one should also turn to the materials of the territorially close Empire of China. This state possessed not only a powerful military and cultural capacity which in its time made a significant impact on the political events in the nomadic world and ancient civilizations of East Asia, but also had a developed

Fig. 1. Sculpture from Borili.

sculptural tradition going back to times of deep antiquity long before the appearance of the Old Turkic military and political entities.

Statue attribution

Continuing the analysis of the Borili statue, we would like to draw attention to one very curious circumstance. In fact, the posture of the represented person (standing position, both hands resting on weapons) is more likely to belong to a guardian than to a feasting hero with a cup in his hand (the main character of Old Turkic stone sculptures, who probably was perceived in this way, at least at the initial stage of the ritual use of this sculpture). However, even though the postures of Old Turkic sculptures were canonically established, there were variants, which differed in terms of the position of the left hand: on the belt, on the abdomen, on the handle of a bladed weapon, on the body of the vessel together with the right hand, or on the left knee as for example is the case with some skillfully made, almost round sculptural images discovered in Mongolia. We are deliberately focusing on the basic visual elements which had the most important meaning for the viewers, being associated with the generally understandable “language” of conventional signs and gestures. In the overwhelming majority of cases when we consider male representations, such significant elements are the vessel, belt, bladed weapon, and torque. And if the latter three elements in different combinations designated the status of the character, the vessel marked a specific subject of a sacral kind. In advance, we should note that depending on the urgency of the moment and the general scenario of the sacral ceremony (funeral feast, commemoration ritual, appeal to the spirit of the sacralized ancestor-patron, personal appeal, etc.), the meaning of the hand gesture with the cup would change. It can, for example, be interpreted as a sign of good will, the act of reception or, conversely, handing over the vessel, symbolic exchange of its contents between the person represented in stone and his relatives and descendants, etc. In fact, precisely the absence of the “feasting bowl” and its replacement with the battle axe—a dangerous weapon of close combat, which the medieval warriors of Eurasia used on the territory expanding from the banks of the Amur River to the valleys of the Rhine and the narrow fjords of Northern Europe, significantly changed the sacral meaning of the statue under consideration. The axe as a weapon of military struggle was also certainly known to the representatives of the ancient Chinese civilization which, as recent discoveries show, was the initiator, if not the trendsetter, of many popular forms of weaponry for the “northern barbarians” (various groups of cattle breeders whose herds grazed at the Chinese borders). The local elite was especially affected by the “charm” of the material and spiritual culture of the Great Empire. It is not difficult to find examples. Even in the Xiongnu period, the highest nobility of the Xiongnu Empire buried its representatives according to the Han norms of funerary rite with the corresponding architecture of funerary structures and a large number of high-quality objects manufactured by artisans from imperial workshops (Polosmak, Bogdanov, 2015: 53– 109, 119–132). The situation did not change much in the Middle Ages, in the Tang period, which can be confirmed by the “mausoleums” of Tonyukuk, Bilge Khagan, and Kul Tigin. The latter “mausoleum” was actually constructed by Chinese builders who were sent there with signs of “respect”, appropriate for the steppe mentality. These structures included the so-called path of the spirits (Shendao, Guidao, Shenlu) (Komissarov, Kudinova, Soloviev, 2012) with the standard set of stone sculptures including statues of people and animals, set in pairs and included into the single architectural ensemble of the necropolis. According to the surviving beliefs, the souls of the deceased would walk along this path, and the creatures embodied in stone would defend them. The earliest “valley of the spirits” can be found in the burial of the Commander Huo Qubing mu (140– 117 BC), and the first of the known monumental sculptures were set up in 120 BC (Kravtsova, 2007: 495, 496; 2010). We should emphasize that the main features of the “path of the spirits” that had been established during the Han period, remained the mandatory elements of elite, and mainly of imperial, burials in China until the Ming (1386–1644) and Qing (1644– 1911) dynasties inclusively. A.V. Adrianov observed and photographed a complex of dignitaries and creatures from the mythological bestiary, created according to the standard norms of the medieval Chinese sculptural tradition, on the left bank of the Ulug Khem in 1916 (Belikova, 2014: 116–120, fig. 43–50). Judging by the pictorial canon and mutual arrangement of the statues, they represented the remains of such a “path of the spirits”, once associated with the funerary complex of the highest nobility, which has now disappeared. Adrianov rightly correlated the find in Tuva with the eastern tradition and believed that it was left “by the Chinese during their stay here” (Ibid.: 117). The fact that stone was processed by Chinese artisans does not raise doubts, as opposed to a further attribution of the sculptures to a visiting imperial official. Given the eternal and even in the recent past unshakable Chinese tradition of returning the deceased (even from the most remote regions) for burying them in the historical homeland, it is highly probable that the burial complex at the Ulug Khem was built for a local noble man. Relatively recently, a burial mound of the mid-7th century was studied at the site of Shoroon Dov in Mongolia, where one of the major local officials from among the tribal nobility appointed by the Chinese administration was buried (see (Danilov, 2010)). A stone slab with an epitaph in Chinese, and a series of terracotta figures of people and animals were found there. The tradition of placing them in funeral complexes existed in China already in the era of the Qin and Han dynasties (from the last quarter of the 3rd century BC to the first quarter of the 3rd century AD). Epitaphs, carved on massive stone slabs in Chinese and dedicated to local officials, were also found on the territory of present-day Kyrgyzstan (Tabaldiev, Belek, 2008: 165, 167, 168). An important semantic element of elite burials belonging to the highest imperial nobility of Ancient China were voluminous, at times huge, dragon-like stone turtles, symbolizing eternity. High (over 3 m) stelae with extensive epitaphs were set up on their backs. A huge marble turtle and similar stele with runic and Chinese inscriptions belong to such structurally important components of the famous funeral complex of Kul Tigin. Judging by the abundance of such various-sized dragon-like armored reptiles that have been found in Mongolia (Mengguguo gudai youmu…, 2008: 206, 230, 282, 283, 288), and pieces of stelae, the Chinese funerary tradition with the statue series of visualized sacral characters was quite popular among the aristocratic environment of the Old Turkic society. Notably, Tonyukuk, the famous military and political figure of the Second Turkic Khaganate, and the adviser to Kul Tigin and Bilge Khagan, was educated in the capital of the Tang Empire in the spirit of the Chinese culture. And military clashes and “devastating” campaigns that are mentioned in the epistolary sources of the steppe warriors, as well as confrontation with the Tang dynasty of China, turned out not to be so important. The centuries-old technological dominance of the Empire, its wealth, luxury, vastness of territory, rigid centralization of power, and rapidly restorable military capacity could not but affect the imagination of the steppe aristocrats, who felt like they stood on the same level as the rulers of the Empire by copying the dominant elements of the neighboring high and sophisticated culture. Accordingly, the local elites of lower rank also began imitating their leaders and reproduce (in accordance with their understanding and capabilities) the prestigious attributes together with forms of their demonstration, adapting them to the traditional norms of life. However, the greater the distance, the more the processes of such “acculturation” lost their bright ethnic flavor. Stone turtles and stelae with epitaphs are not known on the territory of the Altai Mountains, and stone sculpture there for the most part looks much more primitive, which however does not exclude a series of expressive statues executed at a high level, most likely by professional artisans. As far as the southern part of Altai and Xinjiang as a whole are concerned, at least 200 sculptures of various types were known there already in the 1990s, and their number is constantly growing (Wang Bo, 1995; Wang Bo, Qi Xiaoshan, 1996; Xu Yufang, Wang Bo, 2002; and others)*.

At the present time, we can establish the presence of remarkable high-quality sculptures of Old Turkic forms in Xinjiang, manufactured most likely by Sogdian artisans. In addition to the manufacturing technique, this is confirmed by the elements of the equipment, the parallels to which can be observed in fresco painting, as well as in stylistic methods of representing hands with the “elegant” position of the slender fingers*. There is nothing surprising about this, since the routes of the Great Silk Road, which passed across this territory, transmitted powerful cultural impulses clearly visible from archaeological materials. An example is the famous Tang funerary piece of portable art, which retained the distinctive appearance of bearded foreigners on foot, riding horses, and leading camels, wearing high headgear and long caftans with lapels**. Stylistic links with the traditions of Iranian-Sogdian art can be noted already on the carved walls of marble sarcophagi belonging to important officials of the Northern Chinese states of the 6th–7th centuries. For example, the carved images on sarcophagus from the tomb of Yu Hong*** represent both scenes from his own biography, and episodes of the Iranian epic legends and Zoroastrian beliefs (Komissarov, Soloviev, Trushkin, 2014). It is curious that stone sculptures of Xinjiang include a representation of a man holding a staff in one hand and vessel in another hand, having a thick beard in the style typical of the Tang clay portable art that reproduced foreign Sogdian characters (Fig. 2)****. Notably, it is easy to recognize the characters of various ethnic origin, including those of Turkic appearance, among similar clay figurines depicting heavily armed riders (Komissarov, Soloviev, 2015: Fig. 3–7). Thus, we may speak about a certain favorable multicultural situation in Northern China and the surrounding areas in the third quarter of the first millennium AD, which is reflected in both the material and spiritual culture*. We should point out that the Turks in Central Asia also practiced the arrangement of settlements of the Sogdian colonists. This affected the economy and culture of the Khaganates, which were characterized by the merging of the traditions of the settled agricultural population, “consisting of a small part of Turks who settled on the land, but mostly originating from the agricultural areas of the predominantly Sogdian population which occupied the main positions in agriculture, crafts, trade, and cultural life of the states, and the nomadic Turkic population which dominated politically and was economically based on nomadic cattle breeding” (Mogilnikov, 1981: 30). The consequences of this situation are reflected in the materials from the territory of present-day Kazakhstan. Old Turkic portable art pieces discovered in that region show explicit parallels to the Sogdian pictorial canons, for example, manifested by “elegant” rendering of hands and gestures, design of braids of the hairdo, etc.

Turning to the Chinese pictorial materials, it is easy to see that the “equipment” of the reproduced images with various kinds of weaponry has a longstanding tradition going back to the Qin period when, for example, the famous Terracotta Army of the first Emperor was supplied with real weapons. We must note the steady tradition of creating figures that seem to lean on the handles of bladed weapons or the striking parts of axes standing in front of them. This feature took final shape in the subsequent period, but can be clearly observed in full-size statues of the officer corps of the Terracotta Army. We should also point out the fact that the pole striking weapon for both cutting and stabbing belonging to the statue was very popular in the military formations of the Celestial Empire, ranging from various bronze flat-bladed spike hammers to pole-axes. Moreover, by the Song period (960–1279), combined axes (double-edged or with an opposing striker), attached to a long haft, became an important attribute of images of the highest military hierarchy or sacred warlike characters, including female spirits (Liu Yonghua, 2003: 133, k-20.2; 121, k-4). Another attribute of our statue from Borili, which finds parallels both in the pictorial tradition and in the arsenal of the military equipment of ancient China, is the bladed cutting and stabbing weapon with a ring-shaped pommel, which was already known during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25– 220) (Yang Hong, 1980: 124). Once again, we should emphasize that the figure with weapons in both hands does not correspond to the pictorial standard of Old Turkic societies, associated with the required depiction of a vessel in the sculptural composition. Weapons in

*Subsequently, it was severely suppressed and did not develop further for reasons which need additional comprehension.

Fig. 2 . Representation of Sogdians in the clay portable art of the Tang Dynasty ( 1–3 ) and stone sculpture of the Old Turks ( 4 ).

1 – Museum of the city of Altay in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region; 2–4 – Shaanxi History Museum.

both hands, even if they were not drawn, in a state of combat readiness, radically change the perception of the sculpture by both contemporary viewers, who only vaguely know about the ideas behind that object, and medieval viewers, for whom they were simple and understandable. With all possible interpretations, the inevitable and probably the main emotional impulse emanating from the armed character was connected, if one may say this, with a threat message. It can have both an apotropaic function, carrying out a sacred defense and demonstrating the heroic past of the character (good for his own people and dangerous for strangers), and a broadcasting function, manifesting the strength and firmness of the potestary power, whose might guarantees the stability of the hierarchy of social structures in society. Be it as it may, the very perception of the direction of the “vector of power” is associated with the position occupied by the participant in the ritual or visitor to the memorial complex in the system of his own worldview as well as cultural and historical coordinates regarding the reproduced fragment of the event scenario. In this case, two images (of the ruler and of the already mentioned guardian) most closely match the emotional message embodied in the Borili statue. Let us turn to one, in our opinion, important circumstance. Required characters of the “path of the spirits” near the funerary complexes included the statues of guardsoldiers with bladed and pole weaponry. They could hold the weapons in their hands, lean on them, or demonstrate their presence in some other way. We should note that in this case we are speaking only about the typological similarity of the compositional idea, while the sculptures show considerable differences in terms of manufacturing technique and style. The sculpture from Borili undoubtedly represents a Turk, and is executed following the canons of the Turkic sculptural tradition or under its influence. It is quite possible that this object of portable art once served as one of the guardians of the “path of the spirits” accompanying the immaterial essence of the deceased to the place of his afterlife stay, and by its presence marked some kind of extraordinary status of the buried. An indirect argument in favor of such

a hypothesis can be the presence of a barrow structure in the immediate vicinity of the place where the statue was discovered. However, before the archaeological research of this funeral complex and, accordingly, before its chronological and cultural-historical interpretation, such an association has no reliable scholarly significance. We should only repeat that the burial practices of the powerful southeastern neighbor might have influenced the development of the tradition of marking the sacred space around the burials of socially important persons belonging to the “barbarian” population of the adjacent territories. The seeds of such ideas fell on fertile soil and sprouted at the right moment, which manifested itself in the desire of the local aristocracy to reproduce a number of visual characteristics belonging to the funeral ensembles of the “civilized” neighbors in the very same period of the Early Middle Ages, when the processes of cultural interaction were particularly strong.

At the same time, one should not abandon the usual approach to interpreting Old Turkic sculptures as the attributes of so-called enclosures, found in the mountain and foothill areas where the monuments of the Old Turkic complex occurred, and associated by the scholars with the cycle of commemoration rituals. However, in our case, considering the non-standard appearance of the sculpture, we will have to recognize certain changes in the beliefs of the group of the population that left the statue. These changes are manifested by departing from the “universal” norms which dictate the need for representing the vessel. Accordingly, it is also possible to assume certain changes in ritual actions associated with funerary practices and the subsequent use of the sculpture in the sacral life of the community. In this case, we may also assume the existence of a series of similar sculptures and to expect their discovery at least on the nearest territory. After all, being sufficiently conservative, the traditional worldview would require the repetition of the entire cycle of ritual actions and associated attributes for ensuring the welfare of the immaterial essence of the deceased, and consequently, of the community, after it had accepted that canon in such an important area for the community as the demise of its member.

And finally, we should propose one more hypothesis, although the least probable of all, based on the existence of a large number of early parallels from the territory of the most ancient states of East Asia to the iron blade with the ring pommel represented on the statue. Most likely, this weapon along with other elements of spiritual and material culture, spread over the nomadic Ecumene from that region. This circumstance makes it possible to suggest that the example of the sculpture from Borili reveals the initial stages in the formation of the Old Turkic statuary tradition.

Conclusions

It is important that the sculptor who created the statue at Borili ignored the tradition by replacing the vessel with a “non-canonical” attribute. Such deviations are very rare; one such example is a rather realistic sculpture from the Karagash locality (Central Kazakhstan), which represents a male wearing a lapelled robe and holding a long staff with both hands (Margulan, 2003: Ill. 89). The closest parallel in terms of territory is the representation of a Turk (figure 19) in the painting on the western wall of room 1 in Afrasiab (Albaum, 1975: Fig. 7; Ermolenko, Kurmankulov, Bayar, 2005). However, the canon of that statue can be correlated with the image of the guardian— an indispensable element of the funerary rite of the Chinese elite, which could have been incorporated into the rituals of the nomadic aristocracy, influenced by the achievements of the culture of the powerful neighboring state. Consequently, there are reasons to believe that the stonecutters who produced such unusual sculptures, were familiar with the examples (and were aware of the significance of the images) of Sogdian and Chinese art, which also represented the Turks. Apparently, the sculptors turned to using the artistic means of highly developed art following the extraordinary demands of high-ranking customers. It is no coincidence that the structure near to which the sculpture from Borili was found, does not look like an ordinary enclosure, but only excavations will make it possible to get a better idea of its design, as well as to confirm the connection between these objects.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation (Public Contract No. 33.2597.2017/ПЧ).

Список литературы An Old Turkic statue from Borili, Ulytau hills, Central Kazakhstan: issues in interpretation

- Albaum L.I. 1975 Zhivopis Afrasiaba. Tashkent: Fan.

- Belikova O.B. 2014 Poslednyaya ekspeditsiya A.V. Adrianova: Tuva, 1915–1916 gg.: Arkheologicheskiye issledovaniya (istoriografi cheskiy aspekt). Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ.

- Danilov S.V. 2010 Shoroon Dov – “zemlyanoy bugor”. Nauka iz pervykh ruk, No. 6: 288–299.

- Ermolenko L.N., Kurmankulov Z.K., Bayar D. 2005 Izobrazheniya drevnikh tyurkov s posokhom. Arkheologiya Yuzhnoy Sibiri, iss. 23: 76–81.

- Ermolenko L.N., Soloviev A.I., Kurmankulov Z.K. 2016 An Old Turkic statue at Borili, Ulytau Hills, Central Kazakhstan: Cultural realia. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, vol. 44 (4): 102–113.

- Komissarov S.A., Kudinova M.A., Soloviev A.I. 2012 O znachenii “alley dukhov” v ritualnoy praktike Kitaya I sopredelnykh territoriy v epokhu Drevnosti i Srednevekovya. Vestnik Novosibirskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta. Ser.: Istoriya, fi lologiya, vol. 11 (10): 29–40.

- Komissarov S.A., Soloviev A.I. 2015 Vsadniki Astany. Vestnik Novosibirskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta. Ser.: Istoriya, fi lologiya, vol. 14 (10): 62–75.

- Komissarov S.A., Soloviev A.I., Trushkin A.G. 2014 Izucheniye mogily Yui Khuna (Taiyuan, Kitai) v kontekste polietnichnosti kulturnykh svyazey perekhodnogo perioda. In Problemy arkheologii, etnografii, antropologii Sibiri I sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. ХХ. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAE SO RAN, pp. 194–197.

- Kravtsova M.E. 2007 Lingqin. In Dukhovnaya kultura Kitaya: Entsiklopediya: V 5 t. Vol. 2: Mifologiya. Religiya. Moscow: Vost. lit., pp. 493–496.

- Kravtsova M.E. 2010 Kho Tsyui-bin mu. In Dukhovnaya kultura Kitaya: Entsiklopediya. Vol. 6: Iskusstvo. Moscow: Vost. lit., pp. 746–747.

- Liu Yonghua. 2003 Zhongguo gudai junrong fushi [Armour and its furniture in old China]. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe. (In Chinese).

- Margulan A.K. 2003 Kamenniye izvayaniya Ulytau. In Sochineniya: V 14 t., vol. 3/4. Almaty: Daik-Press, pp. 20–46.

- Mengguguo gudai youmu minzu wenhua yicun kaogu diaocha baogao (2005–2006 nian). 2008 [Report on archaeological study of cultural heritage of the ancient nomadic peoples of Mongolia (2005–2006)]. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. (In Chinese).

- Mogilnikov V.A. 1981 Tyurki. In Stepi Evrazii v epokhu srednevekovya. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 29–43.

- Polosmak N.V., Bogdanov E.S. 2015 Kurgany Sutszukte (Noin-Ula, Mongoliya), pt. 1. Novosibirsk: INFOLIO.

- Tabaldiev K.S., Belek K. 2008 Pamyatniki pismennosti na kamne Kyrgyzstana: (Svod pamyatnikov pismennosti na kamne). Bishkek: Uchkuk.

- Wang Bo. 1995 Xinjiang lushi zongshu [Overview of deer stones of Xinjiang]. Kaoguxue jikan. No. 9: 239–260. (In Chinese).

- Wang Bo, Qi Xiaoshan. 1996 Sichouzhilu caoyuan shiren yanjiu [Study of steppe stone statues on the Silk Road]. Wulumuqi: Xinjiang renmin chubanshe. (In Chinese).

- Xu Yufang, Wang Bo. 2002 Buerjinxian shiren lushide diaocha [Study of stone statues and deer stones in Buerjinxian]. Xinjiang wenwu, No. 1/2: 38–51. (In Chinese).

- Yang Hong. 1980 Zhongguo binqi lunqun [Study on the history of Old Chinese weapons]. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. (In Chinese).