Antidepressant's long-term effect on cognitive performance and cardiovascular system

Автор: Nasser A.H.S.

Журнал: Cardiometry @cardiometry

Рубрика: Systematic review

Статья в выпуске: 23, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Background: The nature of antidepressants and their adverse effects should be considered when treating severe depression in individuals with psychotic symptoms. Antidepressant prescription rates have risen steadily over the last 30 years, affecting people of all ages. Aim: The goal of this study was to see if depression and antidepressant usage were linked to long-term changes in cognitive function and cardiovascular health. Methodology: Meta-analysis was performed using PRISMA guidelines along with using the SPIDER search framework using related keywords on different search engines i.e. Google scholars, PubMed, Scopus, ISI, etc. Total (n=2256) papers were obtained and assessed for eligibility. Altogether 15 studies were included using databases and other methods. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale examined the grades provided by the data after numerous screenings. Result: A distinct link was found between antidepressants with cognitive performance and the cardiovascular system. Dementia and hypertension were prevailing long-term effects caused by frequent use of antidepressants in chronic and mild depression.

Depression, depressive disorder, antidepressants, long-term effect, cognition, cognitive performance, cardiovascular system

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148326572

IDR: 148326572 | DOI: 10.18137/cardiometry.2022.23.7688

Текст научной статьи Antidepressant's long-term effect on cognitive performance and cardiovascular system

Ali Hassan Salman Nasser. Antidepressant’s long-term effect on cognitive performance and cardiovascular system. Cardiome-try; Issue 23; August 2022; p. 76-88; DOI: 10.18137/cardiom-etry.2022.23.7688; Available from: issues/no23-august-2022/antidepressants-long-term-effect

Data Review

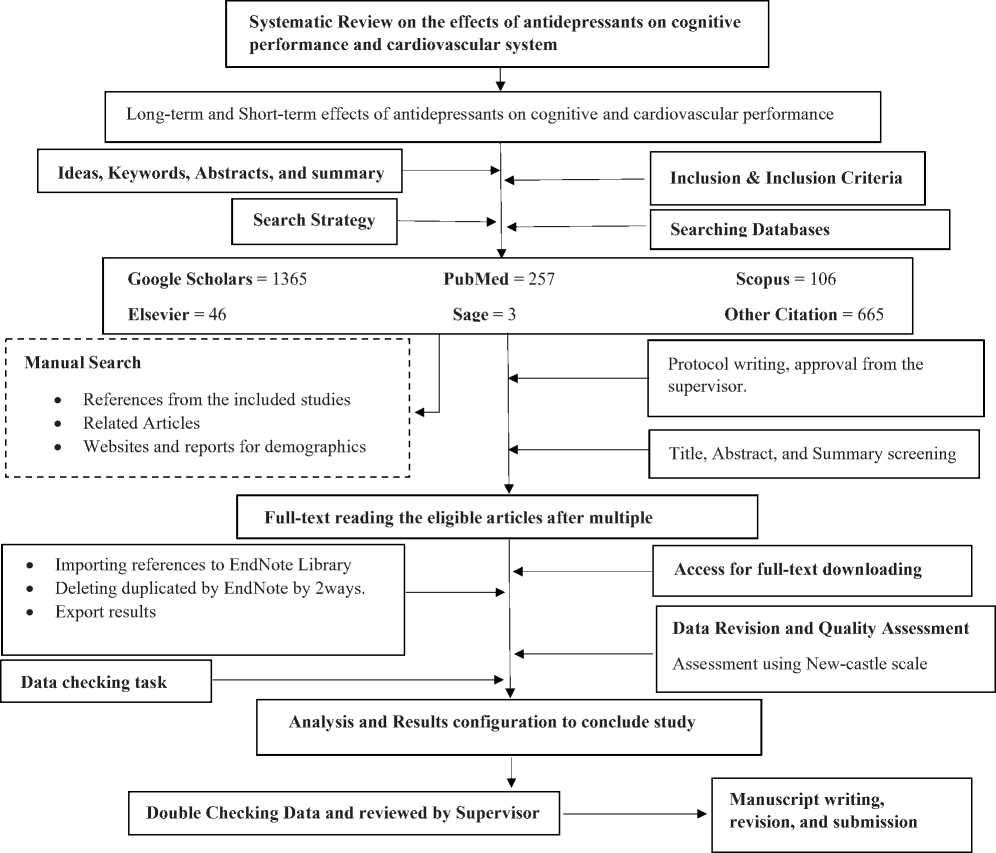

Fig: 3. Flow Diagram of Research Design.

Reviewed Studies:

After many evaluations and considerations, 15 papers were chosen to examine the long-term and shortterm effects of antidepressants on cognition function and cardiovascular system. Between 2012 and 2021, the research papers were published. The studies examined throughout the research had participants from regions all over the world. Antidepressants were linked to cognition and the cardiovascular system in every other trial and review included in the analysis.

Long-term effect of depressants on cognitive performance:

The scientific evidences found on search engines showed prevalence of the disturbed and disoriented cognitive performance effected by the continuous use of antidepressants. 12 out of selected studies showed the effect of antidepressants on cognitive performance. (n = 4) studies [43-46] proved dementia as a long-term residual effect of antidepressants. There was a link between the occurrence of dementia and any antidepressant prescription. Dementia sufferers were found to be depressed in about half of the cases. For depression-complicated dementia, doctors frequently give selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). In rodents, SSRIs have impacts on brain function related to neuronal plasticity, neurogenesis, and neuronal differentiation, and they may help with cognitive performance. A history of depression was compared to be in association with increased risk of dementia, found

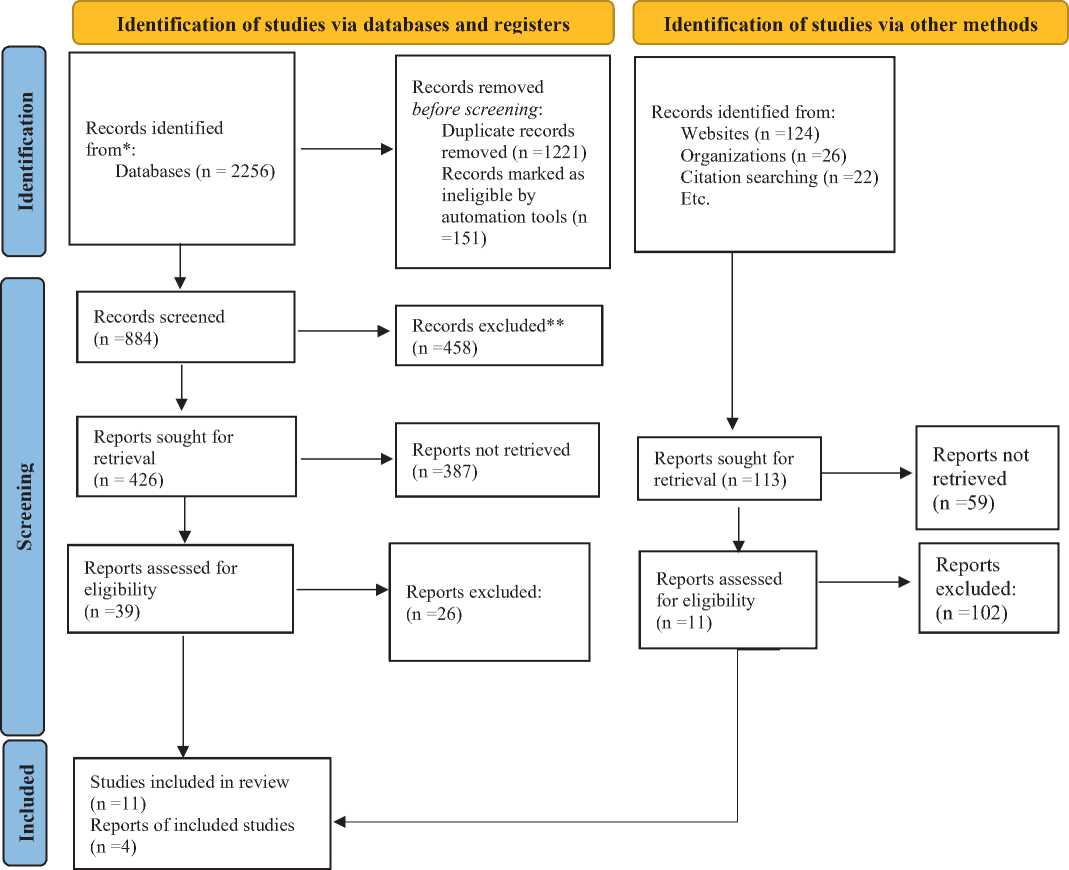

Fig: 4. PRISMA flow diagram of article selection criteria.

in a longitudinal study of older men [47]. The relation between depression and incident dementia was mostly attribuTab. to cases of dementia acquired within the first 5 years of follow-up, after which the relation dissolved.

Antidepressants were associated with less psychotic symptoms, lower functional impairment, and better levels of social interaction in the antidepressant group. Depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and sleep difficulties were more prevalent among individuals on antidepressants than among those who were not [51]. When researchers evaluated the risk of dementia between antidepressant users and nonusers among individuals with depression, they discovered that antidepressant users had a considerably greater risk of dementia than nonusers (Risk ratio ¼ 1.37, 95% Confidence Interval ¼ 1.11-1.70). Whereas, Antidepressant users had a considerably greater risk of dementia than the overall population, according to research comparing dementia risk between antidepressant users and the general population (RR ¼ 1.31, 95% CI ¼ 1.151.49) [45]. The choice reaction time, crucial flicker fusion threshold, and other tests have been reported to be affected by amitriptyline, dothiepin, and trazodone [52]. Furthermore, antidepressant users tend to have remitted depression, although it is uncertain if antidepressant cognitive benefits are attribuTab. to patients’ previous diagnosis of depression.

Long-term effect of depressants on cardiovascular system:

The combination of SSRI (fluoxetine, paroxetine, citalopram, escitalopram) or bupropion with metoprolol or propranolol (37.9% of cases) resulted in a significant increase in the serum concentration of the above-mentioned beta-blockers, resulting in the onset or exacerbation of such side effects associated with the use of those same medications as bradycardia, hypotension, dizziness, and in one case (combination of fluoxetine + propranolol) cardiac arrest [55]. Clopido-

grel should be used with caution in individuals taking antidepressants because of the likelihood of a harmful interaction with bupropion. Three incidences of seizures were reported in the studied material after taking bupropion and clopidogrel together. The increased risk of hyponatremia is another area of interaction between antidepressants and drugs used to treat cardiovascular disorders. It generally refers to the use of SSRI and SNRI together. The serotonin transporter protein may be inhibited by SSRIs, causing serotonin absorption into platelets to be decreased; consequently, this mechanism appears to be linked to adverse effects like longer edema periods or hemorrhagic stroke [56].

Discussion

The main objective to conduct this systematic review was to understand the long-term effect of multiple antidepressants on individual’s cognitive performance and cardiovascular system. Depression is linked to an increased risk of cognitive impairment and cardiovascular disease in general. Antidepressant therapy hasn’t been found to lessen the danger.

Despite the research authors’ adjustments to the risk variables, it’s still impossible to say if depression and/or antidepressants enhanced the risk of cognitive dissonance as claimed. Previous research, on the other hand, revealed that antidepressants might help people with depression improve their cognitive performance. In comparison to the general population, patients with depression, whether or not using antidepressants, had a greater risk of dementia. Antidepressants, particularly SSRIs, were found to cause higher cognitive deterioration and an increased risk of MCI or dementia in people who used them, regardless of their depressive symptoms.

Strong anticholinergic medications have been linked to an increased risk of cognitive deterioration [58]. TCAs were shown to have considerable anticholinergic effects when used as antidepressants. Recent case-control research found that antidepressants with significant anticholinergic qualities, such as amitriptyline and Dosulepin, along with SSRIs without any documented adverse side effects, have both been linked to a higher risk of dementia [46].

Rise in norepinephrine and serotonin levels, perhaps leading to an increase in cardiac sympathetic activity and a modestly increased heart rate with pulmonary circulation stress. Individuals may develop hypertensive, hypoglycemic episodes, and palpitations, however, the risk of ventricular arrhythmias is modest. Patients on SNRIs should have their blood pressure monitored. QRS prolongation, atrial fibrillation, atrioventricular block, ventricular tachycardia, and sudden myocardial infarction are all reported as strong anticholinergic and cardiovascular adverse effects. When compared to SSRIs, TCA usage is linked to a considerably higher risk of stroke. Platelet activation and aggregation are inhibited by SSRIs, which can lead to a loss of homeostasis, irregular bleeding, and a higher likelihood of intracerebral hemorrhages.

There are various limitations to our research. The absence of data on the beginning and recurrence of depressive symptoms, as well as the use of antidepressants throughout follow-up, was the most evident disadvantage of our study design. Another problem to consider is confounding by indication, since antidepressants may have been administered preferentially to more severe instances of depression. The sample size was one of the study’s shortcomings. Regardless matter how many study population studies are conducted; the data is insufficient to calculate for adequate population. Due to language hurdles and unrestricted access to all audiences, the studies gathered and assessed in this systematic review were solely in English. The study may be evaluated in the future using a broad set of data, and in-depth quantitative or mixed method analysis on several obesity characteristics in many populations from various socioeconomic backgrounds can be performed. There’s a strong chance that data buried in other languages has additional creative information for this review research.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our review indicated that the use of antidepressants like SSRIs, TCA, SNRI, and other anticholinergic drugs have an adverse and long-term effect on cognitive performance including dementia and other psychogenic dissonance. Similarly, the prolonged use of these antidepressants showed side effects on the cardiovascular system including stroke, Hypertension and in some cases myocardial infraction. Side effects, particularly impairments of essential bodily organs, must be addressed by healthcare specialists. Regardless of that, for those who don’t have knowledge of the dosage, the physicians should educate the proper use and harmfulness of those suffering from depressive disorders. To improve the validity of results, future research should incorporate self-reported measures with data from health databases.

Appendix 1

Search strategy used in mapping against SPIDER tool

Appendix 2

|

Outcome |

(Cognitive-performance[Title/Abstract] OR Cardiovascular-system[Title/Abstract] |

AND |

|

Type of study |

(cohort[Title/Abstract] OR prospective stud*[Title/Abstract] OR longitudinal stud*[Title/Abstract] OR follow-up[Title/Abstract] Reviews*[Title/Abstract] OR Systematic-Reviews*[Title/Abstract] OR Me-ta-analysis*[Title/Abstract] |

AND |

|

Filters |

(Journal Article[ptyp] AND („2016/01/01“[PDat]: „2022/01/01“[PDat]) AND English[lang]) |

AND |

Appendix 3

The studies included in this systematic review were evaluated for quality.

|

First author, year |

Representativeness of the exposed Variable |

Selection of the unexposed Variable |

Ascertainment of exposure |

Outcome of interest not present at start of study |

Control for important factors or additional factors |

Outcome assessment |

Follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur |

Adequacy of follow-up of Variables |

Total score |

|

[46] |

* |

* |

* |

* |

** |

* |

* |

* |

9 |

|

[48] |

* |

* |

* |

* |

** |

* |

--- |

--- |

7 |

|

[49] |

* |

* |

* |

* |

** |

* |

* |

* |

9 |

|

[47] |

* |

* |

* |

--- |

** |

* |

* |

* |

8 |

|

[50] |

* |

* |

--- |

* |

** |

* |

* |

* |

8 |

|

[51] |

* |

* |

* |

--- |

** |

* |

* |

* |

8 |

|

[45] |

* |

* |

* |

* |

** |

* |

--- |

--- |

7 |

|

[44] |

* |

* |

* |

* |

** |

* |

* |

* |

9 |

|

[43] |

* |

* |

* |

* |

** |

* |

* |

* |

9 |

|

[52] |

* |

* |

* |

* |

** |

* |

--- |

--- |

7 |

|

[53] |

* |

* |

* |

--- |

** |

* |

* |

* |

8 |

|

[54] |

* |

* |

* |

* |

** |

* |

--- |

* |

8 |

|

[55] |

* |

* |

* |

* |

** |

* |

* |

* |

9 |

|

[56] |

* |

* |

* |

* |

** |

* |

* |

* |

9 |

|

[57] |

* |

* |

* |

--- |

** |

* |

* |

* |

8 |

Appendix 3

PRISMA Checklist

PRISMA 2020 Checklist

|

Section and Topic |

Item # |

Checklist item |

Location where item is reported |

|

TITLE |

|||

|

Title |

1 |

Identify the report as a systematic review. |

1 |

|

ABSTRACT |

|||

|

Abstract |

2 |

See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. |

1 |

|

INTRODUCTION |

|||

|

Rationale |

3 |

Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. |

5 |

|

Objectives |

4 |

Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. |

5 |

|

METHODS |

|||

|

Eligibility criteria |

5 |

Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. |

6 |

|

Information sources |

6 |

Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. |

6 |

|

Search strategy |

7 |

Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. |

7 |

|

Selection process |

8 |

Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. |

7 |

|

Section and Topic |

Item # |

Checklist item |

Location where item is reported |

|

Data collection process |

9 |

Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. |

7 |

|

Data items |

10a |

List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g. for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. |

7 |

|

10b |

List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g. participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. |

7 |

|

|

Study risk of bias assessment |

11 |

Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. |

7 |

|

Effect measures |

12 |

Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g. risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. |

7 |

|

Synthesis methods |

13a |

Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g. tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). |

9 |

|

13b |

Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. |

9 |

|

|

13c |

Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. |

9 |

|

|

13d |

Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. |

8 |

|

|

13e |

Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g. subgroup analysis, meta-regression). |

7 |

|

|

13f |

Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. |

7 |

|

|

Reporting bias assessment |

14 |

Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). |

7 |

|

Certainty assessment |

15 |

Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. |

7 |

|

RESULTS |

|||

|

Study selection |

16a |

Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. |

7 |

|

16b |

Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. |

7-8 |

|

|

Study characteristics |

17 |

Cite each included study and present its characteristics. |

8 |

|

Risk of bias in studies |

18 |

Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. |

8 |

|

Results of individual studies |

19 |

For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/ credible interval), ideally using structured Tab.s or plots. |

8 |

|

Results of syntheses |

20a |

For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. |

8 |

|

20b |

Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. |

9 |

|

|

20c |

Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. |

10 |

|

|

20d |

Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. |

Appendix 3 |

|

|

Section and Topic |

Item # |

Checklist item |

Location where item is reported |

|

Reporting biases |

21 |

Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. |

Appendix 3 |

|

Certainty of evidence |

22 |

Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. |

Appendix 3 |

|

DISCUSSION |

|||

|

Discussion |

23a |

Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. |

10-12 |

|

23b |

Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. |

11 |

|

|

23c |

Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. |

12 |

|

|

23d |

Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. |

12 |

|

|

OTHER INFORMATION |

|||

|

Registration and protocol |

24a |

Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. |

- |

|

24b |

Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. |

- |

|

|

24c |

Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. |

- |

|

|

Support |

25 |

Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. |

- |

|

Competing interests |

26 |

Declare any competing interests of review authors. |

- |

|

Availability of data, code and other materials |

27 |

Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. |

- |

For more information, visit:

Author Contributions

Designing, executing, analyzing, and writing this article were the responsibilities of all contributors.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

In the research, writing, and/or publishing of this work, the authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors of this work received no financial assistance for their research, writing, or publishing.

Список литературы Antidepressant's long-term effect on cognitive performance and cardiovascular system

- WHO, Other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. 24.

- Friedrich, M.J., Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. Jama, 2017. 317(15): p. 1517-1517.

- El-Hage, W., et al., Mechanisms of antidepressant resistance. Front Pharmacol. 2013; 4: 146. 2013.

- Hillhouse, T.M. and J.H. Porter, A brief history of the development of antidepressant drugs: from monoamines to glutamate. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology, 2015. 23(1): p. 1.

- Depression Rates by Country 2022. 2022 World Population by Country.

- Roth, G., Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 (GBD 2017) Results. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2018. The Lancet, 2018. 392: p. 1736-1788.

- Schneider, L., Pharmacologic considerations in the treatment of late life depression. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 1996. 4(4): p. S51-S65.

- Thapa, P.B., et al., Antidepressants and the risk of falls among nursing home residents. New England Journal of Medicine, 1998. 339(13): p. 875-882.

- Pilevarzadeh, M., et al., Global prevalence of depression among breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast cancer research and treatment, 2019. 176(3): p. 519-533.

- Hare, D.L., et al., Depression and cardiovascular disease: a clinical review. European heart journal, 2014. 35(21): p. 1365-1372.

- Caeiro, L., et al., Depression in acute stroke. Journal of psychiatry and neuroscience, 2006. 31(6): p. 377-383.

- Ansari, F., et al., The effects of probiotics and prebiotics on mental disorders: a review on depression, anxiety, Alzheimer, and autism spectrum disorders. Current pharmaceutical biotechnology, 2020. 21(7): p. 555-565.

- Laux, G., Parkinson and depression: review and outlook. Journal of Neural Transmission, 2022: p. 1-8.

- Norman, T.R., Antidepressant Treatment of Depression in the Elderly: Efficacy and Safety Considerations. OBM Neurobiology, 2021. 5(4): p. 1-1.

- Lockhart, P. and B. Guthrie, Trends in primary care antidepressant prescribing 1995-2007: a longitudinal population database analysis. British Journal of General Practice, 2011. 61(590): p. e565-e572.

- Abeyta, M.J., et al., Unique gene expression signatures of independently-derived human embryonic stem cell lines. Human molecular genetics, 2004. 13(6): p. 601-608.

- Patten, S.B. and C.A. Beck, Major depression and mental health care utilization in Canada: 1994 to 2000. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 2004. 49(5): p. 303-309.

- Schmidt, H.D. and R.S. Duman, The role of neurotrophic factors in adult hippocampal neurogenesis, antidepressant treatments and animal models of depressive-like behavior. Behavioural pharmacology, 2007. 18(5-6): p. 391-418.

- Malberg, J.E., et al., Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience, 2000. 20(24): p. 9104-9110.

- Dixon, O. and G. Mead, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. J Neurol Disord Stroke, 2013. 1(3): p. 1022.

- Hanlon, J.T., S.M. Handler, and N.G. Castle, Antidepressant prescribing in US nursing homes between 1996 and 2006 and its relationship to staffing patterns and use of other psychotropic medications. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 2010. 11(5): p. 320-324.

- Freedland, K.E., et al., Cognitive behavior therapy for depression and self-care in heart failure patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA internal medicine, 2015. 175(11): p. 1773-1782.

- Oh, S.W., et al., Antidepressant use and risk of coronary heart disease: meta‐analysis of observational studies. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 2014. 78(4): p. 727-737.

- Coupland, C., et al., Antidepressant use and risk of cardiovascular outcomes in people aged 20 to 64: cohort study using primary care database. bmj, 2016. 352.

- Watts, F.N., et al., Memory deficit in clinical depression: processing resources and the structure of materials. Psychological Medicine, 1990. 20(2): p. 345-349.

- Weingartner, H., et al., Cognitive processes in depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 1981. 38(1): p. 42-47.

- Byrne, D., Affect and vigilance performance in depressive illness. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 1977. 13(3): p. 185-191.

- Judd, L.L., et al., Effects of psychotropic drugs on cognition and memory in normal humans and animals, in Psychopharmacology: The third generation of progress. 1987, Raven Press.

- Lesman-Leegte, I., et al., Depressive symptoms and outcomes in patients with heart failure: data from the COACH study. European journal of heart failure, 2009. 11(12): p. 1202-1207.

- Frasure-Smith, N., et al., Elevated depression symptoms predict long-term cardiovascular mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Circulation, 2009. 120(2): p. 134-140.

- Albert, N.M., et al., Depression and clinical outcomes in heart failure: an OPTIMIZE-HF analysis. The American journal of medicine, 2009. 122(4): p. 366-373.

- Sherwood, A., et al., Relationship of depression to death or hospitalization in patients with heart failure. Archives of internal medicine, 2007. 167(4): p. 367-373.

- Jiang, W., et al., Relationship between depressive symptoms and long-term mortality in patients with heart failure. American heart journal, 2007. 154(1): p. 102-108.

- Rumsfeld, J.S., et al., Depression predicts mortality and hospitalization in patients with myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure. American Heart Journal, 2005. 150(5): p. 961-967.

- Jiang, W., et al., Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Archives of internal medicine, 2001. 161(15): p. 1849-1856.

- O’Connor, C.M., et al., Antidepressant use, depression, and survival in patients with heart failure. Archives of Internal Medicine, 2008. 168(20): p. 2232-2237.

- Rutledge, T., et al., Depression in heart failure: a meta- analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. Journal of the American college of Cardiology, 2006. 48(8): p. 1527-1537.

- Jiang, W., et al., Characteristics of depression remission and its relation with cardiovascular outcome among patients with chronic heart failure (from the SADHART-CHF Study). The American journal of cardiology, 2011. 107(4): p. 545-551.

- Serebruany, V.L., et al., Platelet/endothelial biomarkers in depressed patients treated with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline after acute coronary events: the Sertraline AntiDepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHART) Platelet Substudy. Circulation, 2003. 108(8): p. 939-944.

- Page, M.J., et al., Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 2021. 134: p. 103-112.

- Amir-Behghadami, M., SPIDER as a framework to formulate eligibility criteria in qualitative systematic reviews. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 2021.

- Wells, G.A., et al., The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. 2000, Oxford.

- Mawanda, F., et al., PTSD, psychotropic medication use, and the risk of dementia among US veterans: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2017. 65(5): p. 1043-1050.

- Heath, L., et al., Cumulative antidepressant use and risk of dementia in a prospective cohort study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2018. 66(10): p. 1948-1955.

- Chan, J.Y., et al., Depression and antidepressants as potential risk factors in dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 longitudinal studies. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 2019. 20(3): p. 279-286. e1.

- Richardson, K., et al., Anticholinergic drugs and risk of dementia: case-control study. bmj, 2018. 361.

- Almeida, O., et al., Depression as a modifiable factor to decrease the risk of dementia. Translational psychiatry, 2017. 7(5): p. e1117-e1117.

- Xie, Y., et al., The effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia: focusing on fluoxetine with long follow-up periods. Signal transduction and targeted therapy, 2019. 4(1): p. 1-3.

- Guo, M., et al., Metformin may produce antidepressant effects through improvement of cognitive function among depressed patients with diabetes mellitus. Clinical and experimental pharmacology and physiology, 2014. 41(9): p. 650-656.

- Tsai, L.-H. and J.-W. Lin. A case report on elderly psychotic-like symptoms caused by antidepressant discontinuation. in Annales Médico-psychologiques, revue psychiatrique. 2021. Elsevier.

- Giovannini, S., et al., Use of antidepressant medications among older adults in European long-term care facilities: a cross-sectional analysis from the SHELTER study. BMC geriatrics, 2020. 20(1): p. 1-10.

- Knegtering, H., M. Eijck, and A. Huijsman, Effects of antidepressants on cognitive functioning of elderly patients. Drugs & aging, 1994. 5(3): p. 192-199.

- Leng, Y., et al., Antidepressant use and cognitive outcomes in very old women. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 2018. 73(10): p. 1390-1395.

- Diez-Quevedo, C., et al., Depression, antidepressants, and long-term mortality in heart failure. International Journal of Cardiology, 2013. 167(4): p. 1217-1225.

- Woroń, J., M. Siwek, and A. Gorostowicz, Adverse effects of interactions between antidepressants and medications used in treatment of cardiovascular disorders. Psychiatr Pol, 2019. 53(5): p. 977-995.

- Biffi, A., et al., Antidepressants and the risk of cardiovascular events in elderly affected by cardiovascular disease: a real-life investigation from Italy. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 2020. 40(2): p. 112-121.

- Kahl, K.G., Direct and indirect effects of psychopharmacological treatment on the cardiovascular system. Hormone molecular biology and clinical investigation, 2018. 36(1).

- Carrière, I., et al., Drugs with anticholinergic properties, cognitive decline, and dementia in an elderly general population: the 3-city study. Archives of internal medicine, 2009. 169(14): p. 1317-1324.