Archaeological and anthropological study on the grave of eunuch-official couple serving for a royal court of Joseon Kingdom

Автор: Oh C.S., Song M.K., Han S.H., Kim H.S., Park J.W., Ki H.C., Oh K.T., Kim Y.S., Kim M.J., Shin D.H.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.52, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article presents the findings of the study of a co-burial of a eunuch-official and his wife, found in the city of Uijeongbu, Gyeonggi-do Province, made in accordance with Confucian traditions during the Joseon Dynasty period. A description of finds, perfectly preserved in the grave sealed with lime-soil mixture and charcoal barrier, is given. The writings on the banners draping the coffins are studied. These say that in the left coffin the husband named Lee was buried; he was an official who oversaw the management of palace goods and held the position that was given only to eunuchs. In the right coffin, according to the writing, there was the body of the wife; she was awarded a lady's rank corresponding to her husband's status. Special focus is given to the description of clothes and fabric on the bodies of the buried. The results of anthropological analysis of the remains are given. Morphological features of the pelvic and skull bones provided the information on the sex of the deceased. According to the condition of the auricular surface of the left pelvic bone, the age of the eunuch-official and his wife was determined as more than 60 years. It is concluded that the research materials significantly supplement the scientific information on the position of eunuch-officials in the society during the Joseon Dynasty period.

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146976

IDR: 145146976 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2024.52.1.134-144

Текст научной статьи Archaeological and anthropological study on the grave of eunuch-official couple serving for a royal court of Joseon Kingdom

The Joseon kingdom’s graves in South Korea have been examined comprehensively by archaeologists, anthropologists, and textile historians. During the 15th to 19th centuries, those graves ( Hoegwakmyo in Korean), where the coffins are usually surrounded by a cement-like barrier, had been built in almost every corner of the kingdom (Shin M.H., Yi, Bok et al., 2008; Shin D.H., Oh, Hong et al., 2021a). In history, the Joseon graves emerged abruptly for political reasons. In the late 14th century, the Confucians of Korea toppled the Buddhists’ politico-cultural hegemony in the country. The Confucians’ subsequent radical reforms targeted the Buddhist’s rituals, especially the funeral ceremonies and the grave types that were prevalent up until that time. Cremation funerals and stone chambers for storing the bones were no longer accepted in Korean society; the tombs and graves had to be changed to a way that was more faithful to Confucian doctrines (Shin D.H., Oh, Hong et al., 2021a).

The structure of Joseon graves followed the orthodox Confucian axioms: the space around the coffin was filled with lime-soil mixture and charcoal, which hardened to a concrete-like block (Shin M.H., Yi, Bok et al., 2008; Shin D.H., Oh, Hong et al., 2021a; Lee et al., 2013). Such solid structures protected the graves reliably from robbers and insects (Shin M.H., Yi, Bok et al., 2008; Shin D.H., Oh, Hong et al., 2021a). In some graves, the buried bodies did not rot, but preserved their original form even after a long period of time (Shin D.H., Oh, Hong et al., 2021a). Korean archaeologists inferred that the presence of “concrete” barriers or charcoal layers in Joseon graves might have induced oxygen deficiencies due to complete sealing effect, and the high temperatures caused by the lime’s exothermic reactions, which contributed to the successful preservation of human and cultural remains (Shin M.H., Yi, Bok et al., 2008; Shin D.H., Bianucci, Fujita et al., 2018: 5, 6; Shin D.H., Oh, Hong et al., 2021a; Oh, Shin, 2014; Chang Seok Oh et al., 2018).

This became very bad news for the descendants, who expected their ancestors’ bodies and cultural relics to rot safely in their graves. Hundreds of years later, as the Joseon burials were investigated by archaeologists, they found well-preserved artifacts and remains that could not be obtained from the other types of ancient or medieval tombs in Korea (Shin M.H., Yi, Bok et al., 2008; Shin D.H., Oh, Hong et al., 2021a; Lee et al., 2013). It gives scientists a chance to examine various circumstances at the time vividly and to supplement their knowledge of the 15th to 19th century Joseon society and its people (Lee et al., 2013; Shin D.H., Oh, Hong et al., 2021a).

Clothing is one of the most crucial cultural remains from Joseon graves. To date, the articles of clothing that are maintained as large collections in institutions or museums throughout South Korea are a great source for a scholarly understanding of dress history before the 20th century (Lee et al., 2013; Song, Shin, 2014; Shin D.H., Bianucci, Fujita et al., 2018: 5–9; Shin D.H., Oh, Hong et al., 2021b). For several decades, studies on mummies found in the graves have also provided valuable information on the health and disease status of Korean people during the Joseon Dynasty period.

However, the findings obtained so far do not provide information evenly on all social classes of Joseon society. Most of the research was conducted on the graves of the Joseon gentry ( Sadaebu ), with higher social status. Burials of other members of Joseon society are very little studied. In the present article, we explore the grave of eunuch-official who worked for the royal court of the Joseon Dynasty. Eunuchs were administrators who handled various things in the royal court. It is difficult to say that the eunuchs were respected by the upper-class people, but they belonged to politically important persons at the time. By duty, they were very close to the Joseon Kings, and often appeared in many historical events at the court; but little is known about their daily lives, because detailed records of them have been very rare in history. Reflecting this situation, historical works specializing in them are also extremely rare to date in Korea. In this sense, the investigation of the recently discovered, eunuch-official couple’s grave is of great academic value in the study of Joseon society.

The purpose of this article is to introduce the obtained information into scientific use.

Archaeological considerations

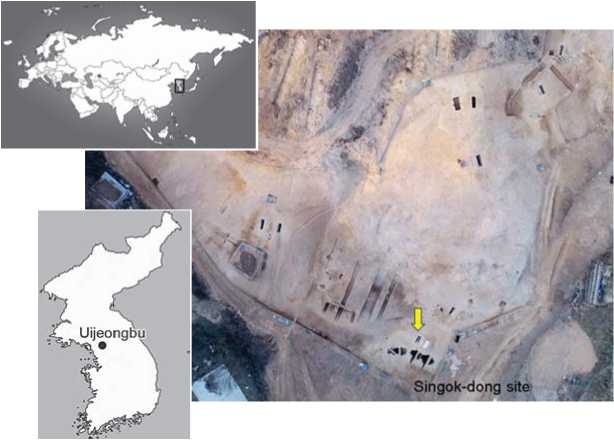

The grave is located in an area (20,283 m²) at Uijeongbu city, Gyeonggi-do (Fig. 1). Since the city has been important in history as a transportation and military hub of the Korean peninsula, many ancient ruins have been reported therefrom. In March 2021, during the construction of new houses and a park, a preliminary archaeological investigation was carried out on this place by the Sudo Institute of Cultural Heritage (Paju, South Korea). The geographical coordinates of our excavation site are 37°43′50.8′′ N and 127°03′44.4′′ E. The excavations were conducted in compliance with South Korea’s Act on the Protection and Investigation of Buried Cultural Properties in Advance of Construction.

The archaeological survey revealed several ruins of residences and graves. Seven graves, belonging to the Joseon period, were covered with a lime-soil mixture barrier. Grave No. 4 was found in excellent preservation; it was completely sealed by a 30 cm thick lime-soil mixture barrier (Fig. 2). Below the barrier, wooden boards with numbers from 1 to 5 could be identified (Fig. 3, A ). The numbers likely represented the order for the placement of boards upon the coffins. After removing the wooden boards, we found banners draping both coffins (Fig. 3, B ). The banners contained writings, which look crucial to confirming the identity of the buried persons. In

Fig. 1. Location of the grave under study (indicated by yellow arrow).

Fig. 2. Grave No. 4 ( A ), 30 cm thick lime-soil mixture barrier ( B ).

Fig. 3 . Wooden boards found below the lime-soil mixture barrier ( A ), two coffins underneath, covered with funeral banners ( B ).

grave No. 4, we found two coffins, possibly those of the couple who were buried together inside the same grave. The coffins were very well preserved and contained clothing and funerary goods. The finds were transported to the laboratory of Eulji University for further scientific research.

Writings on the banners

According to the writings on the banners, the grave was evidently a co-burial of a eunuch-official and his wife. The official ranks they received from the King during their lifetimes could be identified on the banner. In the burials of Joseon period gentry, such coffin banners contained information on the order of official rank, office, position in the office, clan’s name, and full name of the deceased. These data are helpful for revealing the personal identity of a buried individual.

On the left-hand coffin’s banner (Fig. 4, A ) was written “ 通訓大夫 ( tonghundaebu ) 行內

Fig. 4 . Writings on the left ( A ) and right ( B ) funeral banners.

B

А

侍府(naeshibu) 尙洗(sangsae) 李公之柩(leegongjigu)”, which means that the coffin contained the husband’s body. We established that the last name of the deceased was Lee; he worked for the government office as eunuchofficial naeshibu and was awarded an official position that was given only to a eunuch-official sangsae. At this position, he oversaw the management of palace goods such as gunpowder, drugs, candlelight, lantern management, etc. Although the position in the palace was relatively low, the official rank tonghundeabu awarded to him was quite high, which was not uncommon in the hierarchy of the Joseon Dynasty offices. In the writings on the banner, the clan name and full name of the deceased were missing.

On the right-hand coffin’s banner (Fig. 4, B ) was written “ 淑人 ( sookin ) 靈山辛氏 ( youngsan Shin ) 之 柩 ( jigu )”. This means that the eunuch-official’s wife was awarded the lady’s rank sookin by the King, which matches the husband’s rank. Unlike her

husband, the name of her clan youngsan Shin was written on her banner.

Clothing and fabrics on the deceased’s body

The coffin contained the deceased’s body, which was dressed in an officer’s coat and tightly wrapped with multiple other clothes and textiles (Fig. 5). The clothes surrounding the deceased’s body were actually worn by the people at the time; therefore, they were important materials for the research of clothing history in Korea.

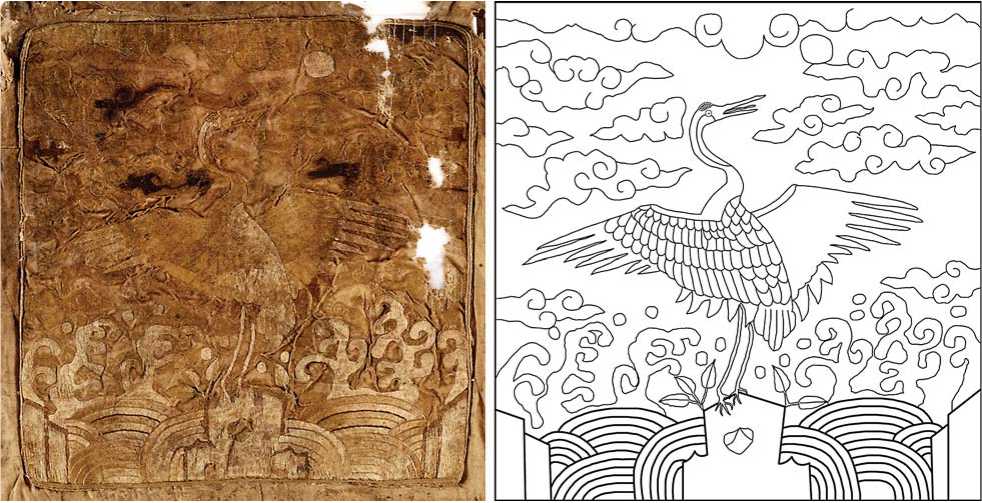

From the eunuch-official’s coffin, we acquired a number of clothes and fabrics ( n =20) (Table 1). In the process of investigation, we first collected a jungchimak (‘man’s coat’) and otshi (‘muff’) (Fig. 5, A ). The dead body was surrounded by a daeryeomgeum (‘quilt’), which was well tied with horizontal and vertical straps to prevent it from being dismantled (Fig. 5, A ). After loosening the surrounding quilt, two jeogori (‘jacket’) were identified below it (Fig. 5, B , C ), and thereunder we could see the danryeong (‘officer’s coat’) that the deceased seemed to have worn during his lifetime. On the chest part of the officer’s coat, a large embroidered painting of a crane was attached (Fig. 6, 7), which was a symbol worn by officials of different ranks. Two cranes corresponded to the status of the highest officials of the Joseon Dynasty. The eunuch’s coat had only one crane, which meant that the man held a more modest position. His danryeong is almost identical to those of other Joseon bureaucrats of the 17th–

Fig. 5 . Jungchimak man’s coat (26) and daeryeomgeum quilt (30) ( A ), two jeogori jackets (31, 32) ( B ), jeogori jacket (32), and daeryeomgeum quilt (30) ( C ).

Table 1. List of finds

|

No. |

Item |

Material |

Features |

|

From the wife’s coffin |

|||

|

1 |

Myeongjeong |

Silk |

A flag that lists the official rank and name of the deceased, leading the way in front of the funeral bier; during the burial, it covers the coffin; red-colored; writings identified |

|

2 |

Hyeonhoon |

ʺ |

Red- and yellow-colored fabrics; a gift of cloth to the Gods |

|

3 |

Guii |

ʺ |

The cover of a coffin |

|

4 |

Onang |

ʺ |

Small pouch, writings identified |

|

5 |

Ibul (Daeryumgeum) |

ʺ |

Quilt used for bundling; brown-colored |

|

6 |

Jeogori |

ʺ |

Jacket; brown-colored |

|

7 |

Daedae |

ʺ |

Belt; red-colored |

|

8 |

Wonsam |

ʺ |

Woman’s ceremonial robe |

|

9 |

Jeogori |

ʺ |

Jacket; no-colored |

|

10 |

Jeogori |

ʺ |

Jacket; purple-colored |

|

11 |

Jeogori |

ʺ |

Jacket; no-colored |

|

12 |

Chima |

ʺ |

Skirt |

|

13 |

Baji |

ʺ |

Trousers |

|

14 |

Baji |

ʺ |

ʺ |

|

15 |

Baji |

ʺ |

ʺ |

|

16 |

Gwadu |

ʺ |

Sash |

|

17 |

Moja |

ʺ |

Hat |

|

18 |

Myeokmok |

ʺ |

Face cover |

|

19 |

Seupshin |

ʺ |

Shoes |

|

20 |

Aksu |

ʺ |

Gloves |

|

21 |

Toshi |

ʺ |

Muff |

|

22 |

Jiyo |

ʺ |

Funeral rug |

|

From the coffin of eunuch-official |

|||

|

23 |

Myeongjeong |

ʺ |

A flag used for funeral; writings identified |

|

24 |

Hyeonhoon |

ʺ |

A gift of cloth to the Gods |

|

25 |

Cheongeum |

ʺ |

Funeral small duvet |

|

26 |

Jungchimak |

ʺ |

Man’s coat |

|

27 |

Po |

ʺ |

Coat. Fragmentary |

|

28 |

Ibul |

ʺ |

Duvet |

|

29 |

Toshi |

ʺ |

Muff |

|

30 |

Ibul (Daeryumgeum) |

ʺ |

Duvet |

|

31 |

Jeogori |

ʺ |

Jacket |

|

32 |

Jeogori |

ʺ |

ʺ |

|

33 |

Samo |

ʺ |

Official’s hat |

|

34 |

Myeokmok |

ʺ |

Face cover |

|

35 |

Gadae |

ʺ |

Belt |

|

36 |

Danryeong |

ʺ |

Official’s coat |

|

37 |

Aksu |

ʺ |

Gloves |

|

38 |

Yeompo |

Cotton |

Rope for bundling |

|

39 |

Dongjeong |

Silk |

Decoration of a collar |

|

40 |

Som |

Cotton, wool |

Cotton (found below the chin) |

|

41 |

Jonggyo |

Cotton |

Rope for bundling (longitudinal) |

|

42 |

Hoenggyo |

ʺ |

Rope for bundling (horizontal) |

Fig. 6 . Under the jeogori jackets, a gadae belt (35) and a danryeong officer’s coat (36) were found ( A ), an embroidered painting (asterisk) was attached to the officer’s coat ( B ).

18th centuries (Fig. 8), showing his status as a governmental official.

The wife’s coffin yielded clothes and fabrics (Fig. 9, 10). The collected clothes were moved to the laboratory of Seoul Women’s University. Some clothing could be successfully restored and researched (Fig. 11).

Anthropological study

After investigation of the bundle of clothing, an anthropological survey was conducted on the bones from the tombs of the eunuchofficial and his wife. The sex estimation was conducted by morphological differences: indicators of pelvic dimorphism were chosen as the main criteria (left pelvic bone) (Buikstra, Ubelaker, 1994); and those of skull structure as the secondary criteria (Ibid.: 19–21; White, Folkens, 2005: 387–391] (Table 2). Sex differences in the structure of the studied skeletons are quite distinct and well consistent with archaeological criteria.

Fig. 7 . Embroidered symbol on the danryeong officer’s coat.

The age estimation was conducted only for auricular surfaces of the ilia, owing to the loss of symphyseal surface in pubic bone (Lovejoy et al., 1985) (Table 3). The analysis has shown that both the eunuch-official and his wife were over 60 years old. Stature estimation based on long-bone length was conducted by the method of Fujii (1960). The estimated statures of eunuchofficial and his wife were 177.4 cm and 141.5 cm, respectively. As for pathological findings, in the case of the eunuch-official, a healed fracture of the left 3rd rib and osteoarthritic signs in the left and right elbow joints could be identified. As regards his wife, button osteoma was found on her right parietal bone; and osteophytes were observed on her vertebrae. Since the two individuals were thought to have been aged 60 or older, it is natural that degenerative changes could be observed in their bones.

Discussion

In Korean history, eunuch-officials in the King’s court appeared in the Unified Silla Period (676–935 AD) (Jang, 2003: 11–12). Their duties included food management in the palace, delivery of orders from the King, cleaning of the palace, etc. They didn’t come to the front of the political arena of the kingdom. However, since the eunuch-officials worked near the King, there was always a possibility that their political power might have become more enlarged than necessary. To prevent this situation, they were always checked by gentry or other courtiers throughout the Joseon Dynasty period. Nevertheless, eunuch-officials of the Joseon Dynasty sometimes took part in important political events of the kingdom, thus often rising to very high positions in the government (Ibid.: 159–185).

Fig. 8 . The portrait of Jeong Jae-Hwa (1754–1790), by courtesy of Suwon Hwaseong Museum (Suwon, South Korea).

Fig. 9 . Jeogori jackets (9, 10) from the wife’s coffin.

Fig. 10 . Baji trousers (13–15) and gwadu sash (16) ( A ) from the wife’s coffin; a sewing mark on the cloth ( B ).

Fig. 11 . Wonsam woman’s ceremonial robe (8) from wife’s coffin.

Table 2 . Data for sex determination

|

Feature |

Eunuch-official |

The wife |

Feature |

Eunuch-official |

The wife |

|

Main criteria * |

Minor criteria |

||||

|

Greater sciatic notch |

5 |

1 |

Nuchal crest |

2 |

2 |

|

Pre-auricular sulcus |

None |

Present |

Mastoid process |

3 |

1 |

|

Subpubic angle |

Narrow |

Wide |

Supraorbital margin |

2 |

2 |

|

Ischiopubic ramus |

Broad |

Sharp |

Glabella |

2 |

1 |

|

Subpubic concavity |

– |

– |

Mental eminence |

5 |

2 |

|

Ventral arc |

– |

– |

*For left hip bone.

Table 3 . Data for age determination *

|

Feature |

Eunuch-official |

The wife |

|

Auricular Surface |

||

|

Transverse organization |

Irregular surface |

Irregular surface |

|

Porosity |

Macro |

Little macro |

|

Granularity |

Destruction of bone |

Depression |

|

Retroauricular activity |

Marked |

Marked |

|

Apical activity |

ʺ |

ʺ |

|

Symphyseal surface |

– |

– |

*For left hip bone.

Eunuch-officials of the Joseon period differed in origin. As compared to the other Asian countries, Joseon’s eunuchs were unique because they could get married and adopted sexually crippled children to form their own families. Mimicking a biological family, they even had a genealogy, consisting of eunuchs who had been adopted by their eunuch-parents for generations. Actually, not all eunuchs in the Joseon society were married, but more than 60 % of them seem to have married women and adopted their eunuch sons. According to the eunuch genealogy Yangsegaebo , published in 1829 and updated in 1920, as many as 578 people were listed in the family of one famous eunuchofficial ( Deuk-bu Youn family), of which 511 people adopted their eunuch sons (Shin M.H., 2005).

In Joseon society, eunuchs were subject to contempt as socially incomplete men. When they became officials in the government, they were commonly expelled from their original kinship families. So, when a eunuch-official formed his own family with his wife and adopted sons, as socially marginalized people, the emotional solidarity between them was not inferior to that of other biological families at all. Although there were Joseon society’s negative feeling against the eunuchs’ families, the tradition could contribute greatly to a eunuch-official’s emotionally stable life (Ibid.).

In the Joseon Dynasty period, eunuchs were socially despised, but it was not uncommon for them to become high-ranking officials. Owing to the nature of their work in the royal palace, their role in the history of the Joseon Dynasty was never small. Eunuch-officials moved busily backstage but never came out on stage. They couldn’t appear on the surface of politics; therefore, very few detailed records of them are left in history. In this sense, the academic meaning of this article adds significantly to the existing knowledge.

Conclusions

The paired burial of the eunuch-official and his wife is a very rare archaeological find. This determines the high scientific significance of the presented multidisciplinary study.

The eunuch and his wife, who were buried in the same grave, were old at the time of their deaths, but their overall health did not appear to be bad except for some degenerative signs. At the time of burial, the eunuch-official was wearing a uniform that he could have worn during the execution of his official duties in the government. The findings obtained from this research will greatly expand the understanding of the position of eunuch-officials in the society during the Joseon Dynasty period.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT; No. 2022R1C1C1013540). The study was carried out after obtaining a review exemption from the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. 2017–001) and Eulji University (IRB No. EU22-40). Author contributions are as follows. Conceptualization and design of study: C.S. Oh, M.K. Song, D.H. Shin; anthropological data analysis: Y.-S. Kim, M.J. Kim; historical dress works: M.K. Song, S.H. Han, H.S. Kim, J.W. Park; historical analysis: H.C. Ki, M.K. Song, D.H. Shin; archaeological studies: K.T. Oh; writing the article: C.S. Oh, D.H. Shin.