Archaeological collections from the Jomon period in the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera)

Автор: Ivanova D.A.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Paleoenvironment, the stone age

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.52, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article presents an analysis and additional description of archaeological items of the Jōmon period from A.V. Grigoriev’s collection (No. 1294) at the Department of Archaeology of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) RAS in St. Petersburg. The study focuses on the description of decorative motifs and the stylistic attribution of selected samples of pottery. The analysis is based on the published data about the Ōmori shell mound (Tokyo, Honshu Island), visited by Grigoriev in 1878 as a part of the expedition from the Imperial Russian Geographical Society. The early stage of the Japanese archaeology is described with reference to the Ōmori shell mound. Special attention is given to specific features of the Jōmon decorative style. The geographic location of the site suggests that the samples are associated with the Kasori B and Horinouchi styles. Contrary to the Russian tradition, the emphasis is made on stylistic interpretation rather than technology and typology. The combinations of large zonally arranged rectangular designs and spiral motifs are typical of the Kasori B style, to which several samples belong. Others reveal vertically and horizontally arranged patterns consisting of incised arcuate and straight lines, typical of the Horinouchi style.

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146991

IDR: 145146991 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2024.52.2.029-036

Текст научной статьи Archaeological collections from the Jomon period in the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera)

The last three years have forced many Russian scholars of international archaeology to focus on new research areas. The impossibility of traveling abroad to work with archaeological collections or participate in international expeditions has fostered the search for previously unused sources. Despite the fact that, in most cases, foreign evidence is studied using the published sources, direct work with collections is an important aspect of any scholarly project. The search for new sources often leads to discovering neglected evidence. In our case, it turned out to be unique archaeological collections from the Jomon period, brought by Russian researchers from Japan in the late 19th–early 20th centuries. This article presents a preliminary analysis of pottery from the collection of A.V. Grigoriev (No. 1294), which is now kept in the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) (MAE RAS).

Although these archaeological materials from the Jomon period were transferred to the MAE in the early 20th century and were brought to Russia in the late 19th century, they have been barely mentioned in Russian historiography. An exception is the article by L.Y. Shternberg, The Ainu Problem , published after his participation in the Third Pan-Pacific Science Congress in Tokyo in 1926 (Gagen-Torn, 1975: 212–217). Discussing specific features of Ainu ornamentation, along with illustrations from the work of N.G. Munro Prehistoric Japan (Munro, 1908), Shternberg provided photos of

pottery fragments from the Jomon period in the collection of A.V. Grigoriev: “Fig. 5. Ornamented clay shards found by A.V. Grigoriev in Japan between Yokohama and Tokko [Tokio. - D.I. ], near lake Omori in 1907. MAE, No. 1294” (Shternberg, 1929: 345). For illustrations, Shternberg selected only four pottery fragments out of 131 (No. 20, 33, 54, and 57). These were intended to demonstrate simple forms of ornamentation (zigzags, wavy lines, spirals) that occur both in the Ainu decoration, archaeological collections from Neolithic Japan, and in some cultures of Southeast Asia.

This article continues the research on the pottery complex of the Jomon period, proceeding from active interest in Japanese Stone Age archaeology in Russian historiography.

A.V. Grigoriev’s collections in the MAE: An overview

Specific interest in the collections of A.V. Grigoriev was triggered by the study that the author of this article carried out on the history of the term “Jomon” in the Russian archaeological literature, as well as the evolution of attitudes towards this period in Japanese and Russian archaeology (Tabarev, Ivanova, 2020). Russian scholars became interested in antiquities of the adjacent regions, including the Japanese archipelago, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Initially, ancient cultures of Japan were viewed through the lens of ethnography (“the Ainu problem”). Later, archaeological evidence from the Stone Age began to play a key role. A.V. Grigoriev, I.S. Polyakov, D.M. Pozdneev, K.S. Merezhkovsky, and L.Y. Shternberg were those Russian researchers who could personally study this evidence. Some of these were able to bring collections of pottery and stone tools from the Jomon period back with them (Ibid.: 64-68). We became interested in the materials of Grigoriev collected during his relatively long stay in Japan.

Alexander Grigoriev (1848–1908) was a scholar with a wide circle of interests (zoologist, botanist, geographer, and ethnographer). He happened to be the first Russian scientist to visit Japan in the late 19th century. As a member of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, in the spring of 1879, Grigoriev was sent on a scholarly expedition on the schooner A.E. Nordenskiöld , which arrived at the port of Yokohama on May 1, 1879, and ran aground off the coast of Hokkaido on June 24.

Taking advantage of the unexpected stop and becoming interested in the history and culture of Japan while still in Yokohama, Grigoriev decided to stay in Japan for almost a year. During that time, he managed to become thoroughly acquainted with landmarks of Tokyo, Yokohama, and Hakodate. Fascinated with the Ainu people, Grigoriev acquired ancient illustrated manuscripts and Ainu household items, made collections of photographs, and compiled an album of sketches. Being interested in zoology, he gathered a collection of fish preserved in alcohol. Grigoriev visited the Omori site (Honshu Island) to collect various archaeological items. Safely delivered to Russia, this collection found its place in the Museum of the Russian Geographical Society on October 21, 1880 (Dudarets, 2006). In 1907, the Society transferred the collection to the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera). In the following year, V. Kaminsky compiled the inventory of the collection. An explanatory note was provided on the title page: “A collection of shards, shells, and stone tools from the Japanese midden near Omori, halfway between Yokohama and Tokyo, collected by A.V. Grigoriev and received by the museum from the Imperial Geographical Society in 1907. Total of 131 items”. Several groups of finds can be distinguished in the collection. The vast majority belong to the Neolithic and include decorated and undecorated pottery fragments, the broken spout of a vessel, individual elements of molded décor, a fragment of an anthropomorphic clay handle (mask) (No. 1–60); stone tools, such as flint end-scrapers, blades, complete and broken spearheads and arrowheads, a sinker, an axe, and flakes (No. 61, 64–80); fragments of animal bones (No. 62, 63); shells (No. 81–129); and medieval artifacts—an iron item (No. 130) and a small scroll (No. 131).

Unfortunately, owing to the fragmentary nature of the pottery collection of Grigoriev and absence of intact vessels, the analysis of morphological and stylistic aspects in this work is only the first step towards a full interpretation and attribution of the material evidence. Unable to compare with the reference complexes of the Jomon period, we used the data shared by the Japanese colleagues from Tohoku University (Sendai) during consultations intended to find parallels among the variety of the Jomon pottery styles. A clear link to the site (“.from the Japanese midden near Omori, halfway between Yokohama and Tokyo”) has made it possible to reduce the options to two styles—Horinouchi (Horinouchi shiki doki 堀之内式土器) and Kasori B (Kasori B shiki doki 加曽利 B 式土器)*. Thus, the data on these pottery styles will be used in the analysis of Grigoriev’s collection. In this study, the term “style” is interpreted as a visual characteristic of the Jomon pottery, including decorative composition implying a specific system of different combinations of ornamentations within a single stylistic group (Ivanova, 2018: 178).

The concept of style (yoshiki Ж^ ) within Japanese archaeology evolved throughout the 20th century. It was finally formalized in the works of the outstanding Japanese archaeologist Tatsuo Kobayasi. In general, style is a certain “data package”, which can be obtained from analyzing the pottery complex of a region and period. The uniqueness of the Jomon styles was manifested throughout the entire process of pottery making, and was most clearly expressed in ornamental decoration. Along with the term “style”, Tatsuo Kobayasi employed two more terms important for modern Japanese archaeology: “type” ( katashiki 型式 ) and “form” ( keishiki 形式 ) (Ivanova, Tabarev, 2022: 60–63). Therefore, it is appropriate to describe the pottery from Grigoriev’s collection from the perspective of style (focusing on decorative features), rather than technical-typological classification and production technology.

Historical background: the Omori shell mound, and pottery of the Horinouchi and Kasori B styles

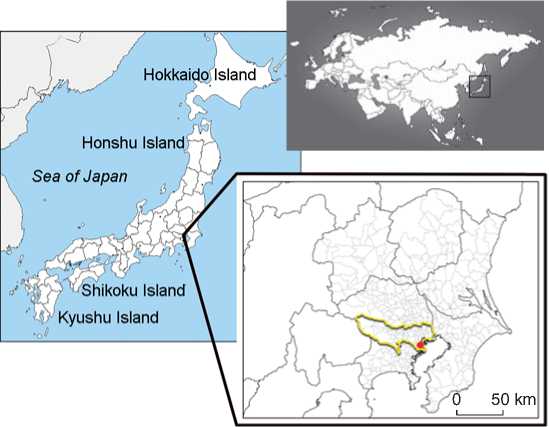

The Omori shell mound is located in the Ota and Shinagawa special wards of the Tokyo metropolitan area (Honshu Island) (Kato Ryoku, 2006: 73; Shin Nihon…, 2020: 66) (Fig. 1). The site was discovered in 1877 by the American zoologist Edward Sylvester Morse, who performed the first scholarly excavations in the history of Japanese archaeology. The emergence of the term “Jomon” is associated with his name, although in fact, according to the sources, Morse never used this term, and in his report on the Omori shell mound from 1879, while describing the pottery, he used the name “cord-marked pottery” (Kobayasi Tatsuo, 2008: 832). The word combination “Jomon pottery” ( Jomon doki ^^±^ ) appeared only in 1886 in the work by Matsutaro Shirai (Tabarev, Ivanova, 2020: 63).

The report by Morse on the Omori shell mound (1879) contained many detailed drawings and descriptions of artifacts (primarily pottery), as well as information on their functional features and parallels from other parts of the world (Kobayasi Tatsuo, 2008: 833–839). The total number of artifacts found during four months (from September to December) was 261, including 214 pottery fragments, 6 doban clay tablets, 23 tools made of bone and horn, 9 stone tools, and 9 shells. Currently, all the finds belong to important national treasures.

Fig. 1. Location of the Omori shell mound.

Notably, the Omori shell mound was known even before excavations by Morse. In 1872, during the construction of the railway, a layer containing shells and broken pottery became exposed after clearing the eastern part of the plateau where the site was located. Morse paid attention to this layer five years later. There is some evidence that in 1873, while exploring a shell midden in the area between Tokyo and Yokohama, Heinrich Phillipp von Siebold found a stone axe and an arrowhead, which were later included in his collection “Japan in the Meiji Era” and were handed over to the World Museum in Vienna. Thus, Morse might not have been the first Western scholar to explore Omori. It is reliably known that H.P. von Siebold continued works at the site in 1877–1878. During his stay in Japan, he studied shell middens and ancient burials over a vast area from Hokkaido to Kyushu. In 1875–1879, his works were published in the German and English languages in Japan, including archaeological studies (“Notes on Japanese Archaeology with Especial Reference to the Stone Age”, 1879). The dispute between H.P. von Siebold and E.S. Morse regarding cannibalism among the ancient population of the Japanese archipelago is also well known (Kato Ryoku, 2006: 60–61, 69; Hirata Takashi, 2008: 139).

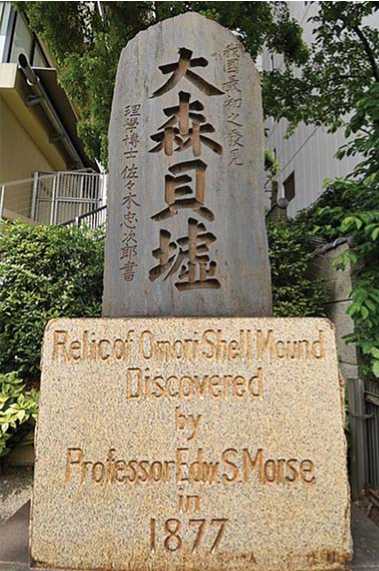

In the first half of the 20th century, two commemorative steles were set up in Tokyo in honor of the Omori shell mound. The first one has the carved inscription “Omori shell midden” ( Omori kaidzuka ЛЙМ§ )* (Fig. 2, b ). The stele was set up in November 1929 in the Shinagawa area near Omori Station (the approximate location of

а

Fig. 2. Monuments in honor of the first scholarly excavations by E.S. Morse.

a - stele with the inscription “Omori shell midden” ( Omori kaikyo 大森貝墟 ), 1930; b – commemorative slab with the inscription “Omori shell mound” ( Omori kaidzuka ЛЙЙ^ ), 1929; c - bust of E.S. Morse in the archaeological park.

’•S ’ -i

b

the Morse’s excavation site). The Japanese politician and businessman Hikoichi Motoyama proposed the idea to honor the merits and contribution of Morse to the development of Japanese archaeology. In April 1930, in the Oota area, near the Tokaido Line railway tracks, a second monument was erected, with the inscription that literally translates as “Omori shell mound” ( Omori kaikyo 大森貝墟 )* (Fig. 2, a ). Thus, two commemorative steles are located in neighboring areas, at a distance of about

c

500 m from each other. This situation resulted from the fact that fifty two years had passed since the discovery of the Omori shell mound, during which Tokyo changed beyond recognition, and in his diary, E.S. Morse wrote that the site was located half a mile (about 800 m) from the station (Kato Ryoku, 2006: 4–10, 21).

In 1955, the area around the steles (about 2857 m2) received the status of a national historical site. Excavations performed in 1979, 1984, 1986, and 1993 over an area of

101,303 m2 revealed the remains of six dwelling pits 30 cm deep, 132 utility pits, and two hearths. Some parts of the site had a layer of shell heap about 1 m. In 1984, the site of the Morse’s original excavation, i.e. around the stele with the inscription “Omori shell mound” in the Shinagawa area, was finally established. In 1986, an archaeological park with exhibition was opened there, and a bust of E.S. Morse was set up (Fig. 2, c ). The main part of the artifacts is kept in the Shinagawa Historical Museum (Ibid.: 81–88).

In addition to a large number of shellfish shells and bones of boar, deer, birds, and fish, the following groups of artifacts were discovered at the site: stone items (spearheads and arrowheads, axes and adzes, dishes, fragments of staffs, pestles, etc.); pottery and clay items (numerous fragments of vessels, ceramic sinkers, beads, ear disks, small fragments of dogu figurines, doban clay tablets); items made of animal bones, horns, and fangs (bone knives, needles, piercing tools, fishhooks, harpoons, arrowheads from boar tusks, carved items of horn, etc.); fragments of human bones.

Judging by the pottery assemblage, the Omori shell mound was actively used by the local population from the mid-Late to the first half of the Final Jomon period. Radiocarbon dates obtained from charcoal indicated an interval of 3500–3000 cal BP, which correlates with the time when the Kasori B , Horinouchi , and Angyo 3 styles spread on the Kanto Plain (4240-3220 cal BP) (Ibid.: 73; Kobayasi Kenichi, 2019: 111–127).

The material evidence from the Omori site included container varieties typical of the Jomon period, such as deep pots ( fukabachi 深鉢 ), shallow pots ( asabachi 浅 鉢 ), jar-shaped vessels ( tsubogata doki 壺形土器 ), and spouted vessels ( chuko doki ^D±S ) (Akita Kanako, 2008: 596; Kano Minoru, 2008: 591). In some areas where the Kasori B pottery was common (mainly in the presentday Saitami and Chiba Prefectures), pots with handles for hanging ( tsurite doki 釣手土器 ) were found, but these were not recorded at the Omori site (Nakamura Kosaku, 2008: 1065).

The Kasori B and Horinouchi styles are distinguished by the division of the fukabachi vessels into two types: A – with curved or bent neck, B – with concave neck. In Japanese archaeological literature, pots of the former type are designated by the term asagaogata doki ( 朝顔形 土器 ) ‘a vessel with a neck in the shape of a loach bell’; the latter type is called kyaripa-gata doki ( ^kU^— 形土器 ) ‘a vessel with a neck in the shape of a caliper’ (Hosoda Masaru, 2008: 412–416). Notably, all these vessel varieties were typical of the pottery styles of the Middle Jomon period, thus revealing a continuity of form.

Decoration compositions on the vessels of the Horinouchi and Kasori B styles included background (cord impressions, “comb”, incised patterns) and main ornamentation. The surface of the vessel was mostly divided into several horizontal ornamental bands, but the Horinouchi style also had vertical arrangement of ornamental patterns. Owing to a clear division into bands, the neck, body, and bottom zones are visually distinguished. The main part of the decoration covers the area from the edge of the rim to the middle of the body.

Decorative elements include patterns of incised lines (straight, wavy, or arched), spiral and zoned geometric patterns, linear appliqués (vertical or horizontal), worn imprints of cord, and rows of rectangular or oval-shaped imprints. A combination of decorated and undecorated details is typical. Rubbing and polishing of the surface were used for creating contrast. As with the shapes of vessels, main decorative elements and technical methods emerged as early as in the Middle Jomon period (Akita Kanako, 2008: 596–597; Kano Minoru, 2008: 587–591; Ivanova, 2018: 176–190).

Overview of the pottery complex and its stylistic features

The greatest interest for stylistic and chronological attribution of Grigoriev’s collection is its pottery assemblage, consisting of 60 inventory numbers and 67 items. We examined the shards and recorded the variants of ornamental patterns. When it was possible to preliminarily restore a part of the vessel from the scattered fragments, the decorative composition was recorded and analyzed.

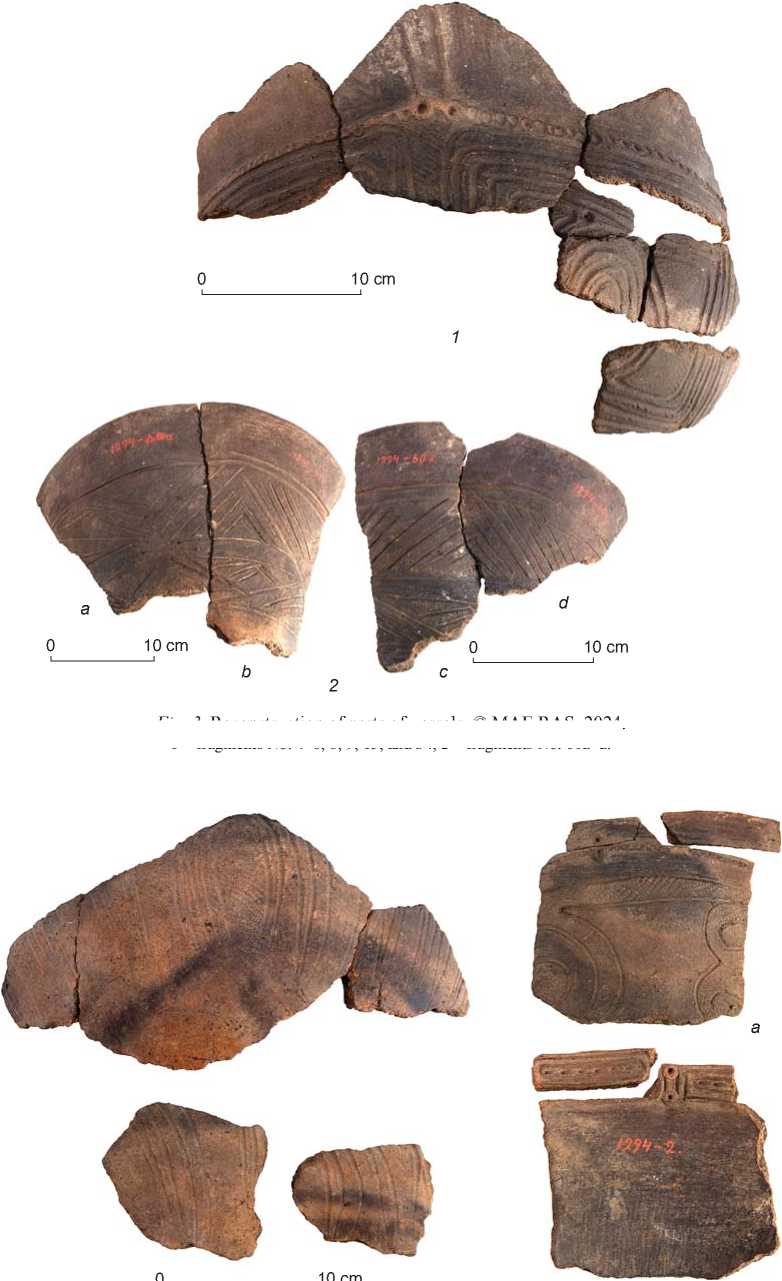

In this study, 25 fragments were selected from collection No. 1294 (22 inventory numbers: 2, 4–6, 8, 9, 11–15, 33, 34, 41–45, 57–59, 60a–d). The determining factor for selection was clearly legible ornamentation and the possibility of reconstructing individual fragments into larger parts that could provide more information for stylistic interpretation. Some of the fragments could be joined together, thereby providing more accurate data on the decorative composition of the three vessels. The sample also contained individual fragments with clearly legible patterns, making it possible to examine different decorative solutions for the Jomon vessels.

After systematization of the pottery in accordance with ornamental patterns, twelve fragments from a single pot were identified: No. 4–6, 8, 9, 11–15, 33, and 34. During preliminary reconstruction, we managed to partially restore the neck area and wall of the body (seven fragments out of twelve), which consisted of fragments No. 4–6, 8, 9, 15, and 34 (Fig. 3, 1 ). The vessel was visually divided into two parts—the undecorated neck with rubbing traces, and the decorated body. This division was emphasized by a horizontal band additionally decorated with round imprints. Ornamentation was concentrated in the body area. A part of a large decorative element in relief— a multilevel zoned rectangular ornamentation with a spiral motif in the center—has survived. The composition was complemented by rubbed imprint of a cord and rounded imprints. This combination of decorative elements was typical of the Kasori B style (Akita Kanako, 2008: 596– 597; Shin Nihon…, 2020: 91).

The second vessel, represented by four large fragments, was No. 60a–d (Fig. 3, 2 ), belonging to the upper part of the body with an undecorated rim. Decoration was typical of the Horinouchi 2 style: rows of horizontally and diagonally drawn lines formed a multilevel and multilayered combination of triangles. The general concept was complemented by unornamented zones. Fragment No. 60b preserved a small section of the lower

b

10 cm

Fig. 3. Reconstruction of parts of vessels. © MAE RAS, 2024. 1 – fragments No. 4–6, 8, 9, 15, and 34; 2 – fragments No. 60a–d.

Fig. 4. Fragments No. 41–45 of one vessel ( 1 ) and fragment No. 2 ( 2 ). © MAE RAS, 2024.

part of the body. It was rubbed out like the rim area (Kano Minoru, 2008: 587–588).

Fragments No. 41–45 were parts of the third vessel (Fig. 4, 1 ). It was possible to join three fragments out of five. The decorative composition was formed by two variants of ornamentation: rubbed imprints of a cord and a pattern of drawn arcuate lines. This combination of elements decorated the entire surface of the body, leaving the lower part of the vessel plain. According to preliminary data, such composition was typical for the pottery of the Horinouchi 1 type B style (Ibid.: 588, 590).

Individual shards also included large fragments with clearly legible patterns. Fragment No. 2 (Fig. 4, 2 ) is noteworthy, since the decoration appears not only on the outer surface of the vessel, but also along the inner edge of the neck, decorated with horizontal zoned rectangular ornamentation filled with a drawn pattern of an ellipseshaped figure with dotted lines in the middle (Fig. 4, 2 , b ). The decorative elements were separated by a vertical pattern of two concentrically shaped imprints connected by parallel incised lines. However, since pots with internal decoration are rare, ornamentation on the outer surface is more informative (Fig. 4, 2 , a ). It is a combination of relief pattern and undecorated zones. The decorative elements were made using drawing technique, and presumably had a shape of figure eight and spiral of alternating bands: decorated with cord prints and undecorated with traces of rubbing. Judging by the shape of the ornamentation and the combination of various decorative techniques, it can be assumed that this is a fragment of a Kasori B style vessel (Akita Kanako, 2008: 596–597).

Conclusions

Currently, the archives of the Department of Archaeology of the MAE RAS contain five collections of archaeological materials from Japan, which were donated by the Imperial Russian Geographical Society in the early 20th century. In addition to the collection from the Omori shell mound (No. 1294), A.V. Grigoriev assembled another collection on the island of Hokkaido (103 stone tools and pottery fragments). This evidence was received by the MAE in 1907, and in 1908 V. Kamensky an inventory of it under No. 822. Collection No. 1295 was brought by I.S. Polyakov from Shinagawa (near Tokyo). Collection No. 1590 includes surface finds from the island of Hokkaido; its author is unknown. The last collection was received in the 1930s (No. 4083). It was gathered by L.Y. Shternberg in different parts of Japan (Nagano, Aomori, and Saitama Prefectures) presumably during his trip to Tokyo for the Third Pan-Pacific Science Congress in 1926.

The collection of archaeological finds from the Omori shell mound (No. 1294) gathered by Grigoriev has been stored in the archives of the MAE for over a century. So far, it has been mentioned only once in an article by L.Y. Shternberg (1929) in the context of the “Ainu problem” and not archaeology of the Stone Age in Japan. This indicates the need for additional elucidation of the collection, since only four pottery fragments out of 67 have been described in publications. The description of artifacts in this article and presentation of parallels with styles of the Late to Final Jomon are only the first steps towards a comprehensive interpretation and attribution of the entire complex of material evidence kept in the collections of the MAE RAS. The study of foreign archaeological collections in the archives of Russian museums at the federal and regional levels is a promising and important research area, especially in the context of modern priorities for the development of the Russian Humanities.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Project No. 19-39-60001). I express my deepest gratitude to G.A. Khlopachev, D.V. Gerasimov, and O.S. Emelina from the Department of Archaeology of the MAE RAS for their assistance with the collections, and to Prof. Kanno Tomonori (Tohoku University) for important consultations on the topic of the article.