Architectural perspective and the private-public continuum in the villas of ancient Stabiae: preliminary considerations

Автор: Telminov Vyacheslav

Журнал: Schole. Философское антиковедение и классическая традиция @classics-nsu-schole

Рубрика: Статьи

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.15, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article serves as a starting point for a research project dedicated to the dichotomy of private and public, and its implications and dynamics in the late Roman republic - early Empire. The primary focus is on the roman private spaces in the villas and houses of the Vesuvian archaeological area. The main methodological approach is represented by the ‘space syntax” theory of B. Hillier and the “movement as memory” theory of D. Favro developed within the logics of Spatial Turn studies, further refined by A. Russel in her works on Roman public space.

Late roman republic, vesuvian archaeological area, roman villas, private and public, spatial turn, space syntax theory, movement as memory theory

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147215916

IDR: 147215916

Текст научной статьи Architectural perspective and the private-public continuum in the villas of ancient Stabiae: preliminary considerations

-

I. Historiography and methodology

A fundamental problem in history that continues up to the present day is the question of where exactly the division between public and private life should be. This question has been discussed for centuries and continues to the present day, remaining relevant in the societies of today.1

The private-public continuum was and remains one of the most important vectors along which many significant political and cultural processes develop. At times, for example, public interests dominated or even trod on the interests of the average citizen or vice versa.

The varying and changing relationship between the public and private matters are often broken down into the following oppositions such as “individualismcollectivism (public interests)”, “personal interest-public”, “democracy (the power of all) and dictatorship (power of the individual)”, “public domain – privatization and commodification”, “lack of control – regulation”.2

For a long time, studying the tensions existing between the limits of public and private were neglected.3 Why? Modern man has found it too tempting to over-simplify the historical record and concepts and force a modern picture based on a modern view. This should be avoided at all costs.

The post-modernistic shifting of the supposition that the ancient understanding was equal to ours has been recently exacerbated by studies that challenged the traditional dichotomy of public and private. Most of the places that we share with strangers are neither public nor private but exist in a gray area between the two.4 The clear distinction is not only impossible but is constantly challenged in many ways, for example, by artists.5 Since this shift occurred, the most important differences between the modern and ancient concepts of public and private have been duly mentioned in a couple of influential works.6

In the scholarly sociology the problem of the contradictory nature of the term public has gained increased focus during the last decades of the 20th century.7

Most influential standpoints follow that of Hanna Arendt, who described “public” as what remains when you take away the economy, the household, and the administrative apparatus of the state.8 Pierre Bourdieu considered the opposition between public and private “as one of the central dimensions according to which the patronage is organized.”9

It is important to underline, that the distinction of private and public was born in the classical Greece as an opposition between oikos (a private household within the domestic sphere of production10) and polis , the space of politics in a multivalent sense of this concept, typical for many concepts of the ancient Greek culture – the place for the exercise of freedom and decision.

The more standard way of referring to the private/public distinction was developed in the Modern times and interprets it as a demarcation between the governmental, public authority and the sphere of voluntary relation between “private” individuals.11

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill drew attention to the fact that a detailed examination is required, particularly of the categories that, from today's perspective, appear to be self-evident. It is necessary not only to understand what was contained in the concepts "private" and "public", but also in what form there were intermediate states or completely different states (for example sacred areas dedicated to the gods - neither private nor public).12

In the recent years, all “spatial” themes have become so widespread as to win their own name (‘The Spatial Turn’),13 an integral part of a post-modernist scholarship. The key underlying idea behind it is that space categories must be under- stood as socially produced variables which are created and experienced differently by different people and cultures at different times.14

Another premise for studying the roman concept of “publicness” is offered by the theory of cultural critics, who consider the public realm as the arena of sociability, a stage for appearing before others,15 and as the space filled with an interplay of an inherent struggle between separate groups of the public which want to turn sections of this space into their own private space. After such usurpation, the process starts again.16

Modern scholars have given a new gender perspective on the problem of pub-lic/private by taking into account that ‘public’ and ‘private’ have historically been associated with a hierarchical gender binary with the ensuing exclusion of women and other oppressed groups associated with the private sphere from power located in the public sphere.17

The study of private and public space are also intrinsically linked to architecture. There are several approaches for the study of movement inside architectural forms: most useful for our topic are ‘space syntax theory’18 of Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson and “movement as memory” approach of Diane Favro19 – both will be used in my research, the first part of which is represented by this article.

Now let us turn our attention to what is implied by the study of public/private relation in Ancient Rome, and what has been done already.

The most representative study of Vesuvian examples, which form the core of my research portfolio during 2013–2015 work in the Restoring Ancient Stabiae Foundation, belongs to Ray Laurence and Andrew Wallace-Hadrill,20 but these examples can now be illuminated in a different light following the revolutionary approach of Amy Russel.

The most prominent works on the Roman villas in general and in the Vesuvian area belong to J. H. D'Arms, J.R. Clarke, J.T. Smith, A. Marzano,21 and the progress and results of current excavation and restoration works in the villas of ancient Stabiae are meticulously reflected in the works of archaeologist Paolo Gardelli, with whom I had the honour to collaborate in the Vesuvian archaeological area.22 These detailed reports contain valuable pieces of evidence about new spaces of the villas coming to light, and, most importantly, interior decorations that can give clues about the private or public functions of certain areas of the villas.

The most fundamental work concerning the opposition of private/public in Ancient Rome remains to be A. Russell’s “Politics of Public Space in Republican Rome” published in 2016. As the title reveals, this brilliant book contains a solid analysis of the Roman concept of publicness and its application. In the book, author set out to explore the multivalency of space in Ancient Rome beyond usual explorations of private villas and took it out to the public space which by default had been considered to be purely public.23

She chose several illuminating examples from a typical Roman public space (i.e., Roman Forum) and explored them in a synchronic and diachronic perspective.

In a more general manner, Amy Russel analyzed the definition of public and private in the Roman world and pointed out to many important nuances,24 also reiterating some of the accepted wisdom about the roman private space.25 Also, the author performed a microcontext analysis of Latin writers with respect to the concepts of private and public26 and revealed a “sliding scale of public and private”.

Since the thorough comparison between different periods of the Late Republic and Empire on a material of less emblematic spaces like villas, urban landscapes and roads were outside of the scope of her iconic work, most of her analysis is dedi- cated only to the chosen examples. She is fully aware of the “flexibility of the terms in our own language and the fact that they vary from one society to the next”,27 and underlines that “The Roman concepts are hard to pin down not just because they are different from our own, but because they were always unstable.”28

Nonetheless, she did not set out to fully explore the dynamics of this unstableness outside the public sphere and whether there were any long-reaching trends within this instability. Therefore, several aspects still wait to be explored.

The purpose of my work is to introduce private and less prominent public urban spaces into the scope of analysis and to apply a diachronic perspective, using the set of suitable approaches and tools developed by the “spatial turn” scholarship: Amy Russel’s “movement, memory and performance” triad, charted transformations of main political spaces in Rome as benchmarks for wider analysis, ‘space syntax theory’ of Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson and the “movement as memory” approach of Diane Favro. To achieve overarching results, the time frame will reach from 2 BCE, with a focus on the Gracchan period, through the transformation of Republic into Empire29 and well into the Late Empire period. This article serves as an introduction to this research project.

-

II. Roman villas in the Vesuvian archaeological area

First of all, to explore the relation of public to private in the ancient Rome means to widen the concept of public space into private area. We will take as a premise the handy definition offered by Margaret Kohn, stating that a public place, although being in actual ownership of the state or a private, is accessible to many people and/or fosters communication and interaction, thus facilitating unplanned contacts between people.30

In case of a Roman villa, this would include the public part of a villa, since it was used for communication between friends, clients and relatives of the villa’s master. To cite just one author, Cicero: in the house of a powerful man “et hospites multi recipiendi et admittenda hominum cuiusque modi multi- tudo” (both many guests need to be received and a crowd of men of all kinds must be admitted)31.

The strikingly good examples of Roman villas with plenty of private and public spaces to study have been preserved by the famous Vesuvius eruption in 79 CE.

Most well-known cities of the Vesuvian archaeological area, Pompeii and Herculaneum, have been closely studied by archaeologists and historians for more than two centuries. Excavations of Herculaneum began in 1738 on the orders of Charles VII of Naples32. 10 years later, in 1748, the amphitheater of the neighboring city of Pompeii finally saw the “daylight surface”.

Currently, the excavated parts of these cities represent a huge open-air museum, which is visited by hundreds of thousands of tourists every year. In Pompeii most of the city's territory has been excavated (44 out of 66 hectares), while only one-fifths part of Herculaneum has been unearthed, the other four-fifths still waiting, as it is partially located under medieval residential buildings.

If no major excavations and discoveries are expected here soon, this does not mean that there is no such place in the Vesuvian area. In fact, the ancient Stabiae south of Pompeii is extremely rich with elite residential structures of the Roman nobility,33 many of which still wait to be discovered.

Unlike Herculaneum, buried under several meters of pyroclastic flow, Pompeii and Stabiae have been covered mainly by volcanic stones (lapilli) and ash. Around the same time, when Herculaneum and Pompeii excavations started, an officially authorized party of “treasure seekers” began to dig trenches and tunnels in the area of the Church and the bridge of San Marco.34

By the standards of modern science, the methods of their work can be called nothing but barbaric: military engineers cut tunnels through the walls of petrified ash, and as soon as they reached the buried walls, they dug along them, carving out frescoes and taking them to Naples.35

The walls did not stop them at all (it was not in vain that they were military engineers): where it was needed, breaches were made right through them so that the “miners” could go deeper. These gaps made by the Bourbon engineers are still present in many places of the villas, while in some other places they have been covered by modern archaeologists.

The first discovered villa was named after the nearby church dedicated to Saint Mark. But for several reasons, the excavations in Stabiae were stopped (e.g., the eruption of 1782, diversion of all available forces and funds for the excavation of Pompeii). The already explored premises of the villas and residential quarters of the city were backfilled, the tunnels were abandoned, and all which remained was a plan of the initial excavations with a grid of lines drawn on it, denoting countless walls, now invisible and once again gone into the underground oblivion.

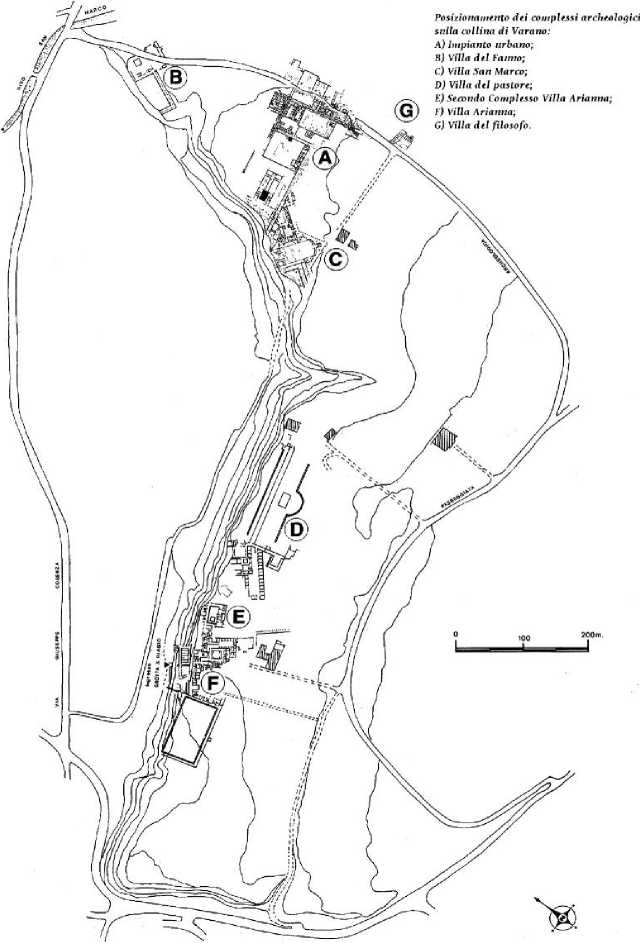

Fig. 1. Villas at ancient Stabiae

These villas re-emerged thanks to Libero d'Orsi, headmaster of a secondary school of the coastal town of Castellammare di Stabia and an ardent fan of archeology. In the beginning, all was based on his enthusiasm: on January 9, 1950, he went to the excavation site in the company of a school guard and a locksmith.

Although more than half a century has passed since the rediscovery of these villas, only a smaller part of the premises has been excavated or explored – even from those indicated on the plan of the Bourbon times. Many rooms and even whole villas remain hidden. Villas San Marco and Villa Arianna are half excavated, the rest are still to follow. Today, archaeologists from Italy, Russia (Hermitage), USA (Columbia University, University of Maryland and Cornell University), and other countries continue to work at these villas.

-

III. Villas San-Marco and Arianna

Villa San Marco, located by the picturesque slope of the Varano Hill, is commanding a perfect view over the Gulf of Naples and Vesuvius. It is the first of two little-known masterpieces of ancient Roman architecture that will be discussed as a starting point of this research. First, however, a brief analysis should be dedicated to the concept of a Roman “retreat” villa (Villa d'otium, villa urbana or villa marittima).

This function determined the external and internal appearance of such buildings. How did the look of a “retreat villa” differ from, on the one hand, a large mansion in a Roman city (Domus) and, on the other hand, from a farm-oriented villa (Villa rustica)?

Representatives of the senatorial nobility could own all three types of estates and visited each of them during a year, inviting friends and relatives. But there were fundamental differences between all three types in architecture (area size, layout, number of certain types of rooms, location) and interior (household items, fresco painting types and other decorations).

Due to the lack of a commercial function that was characteristic of “rural villas”, we will not find grape and oil presses in the garden of a typical “retreat villas” of San Marco and Arianna, as well as a large number of vessels for aging and storage of wine and oil. No craft workshops will be found in the slave part of the estate, and the main efforts of the slaves will be directed to preparing food for the masters' luxurious feasts or heating the bath complex.

The “rural villa” for obvious reasons will be located in the countryside, near olive and fruit groves, and vineyards. The territory of a “retreat villa”, on the contrary, will most likely be limited by the perimeter of its buildings. But in terms of the richness of the interior and the number of various premises, it will many times surpass a rural villa.

What is the difference between a “retreat villa” and rich city mansions of the Roman and provincial nobility, numerous examples of which you can observe in Pompeii and Herculaneum (House of the Faun, House of the Surgeon, House of the Vettii, etc.)? The main difference lies in the physical restrictions of the available area – while the latter is located in an extremely high urban environment, the former usually disposes of larger space. For example, villas of ancient Stabiae sit on a spacious terrace that drops off to the picturesque seashore.

Therefore, the mansions of the rich inhabitants of Herculaneum or Pompeii do not occupy more than one city block. The largest of these houses is the House of the Faun, whose owner successively expanded his estate until it swallowed all neighboring houses (2,970 sq. meters). But countryside villas could be 5 or more times larger than that. For example, the Second Complex villa has an area of approximately 5,500 sq. meters, followed by Villa San Marco with an area of around 13,000 sq. meters, then Villa Arianna which measures 17,000 sq. meters and finally Villa del Pastore which occupies an area of approximately 19,000 sq. meters.

A further major difference lies in the “relationship” between a residential complex and the landscape. City mansions were like fortresses: on all sides, they were surrounded by blank walls. This is understandable: had there been windows, one could see only a fussy crowd hurrying about their business, annoying freedman Postumius selling cheap wine in a shop opposite,36 or slaves from the laundry of Stephanus, carrying packs of dirty clothes all day long. Only the front entrance to a “domus” was clearly distinguished by the size and beauty of its decoration to reflect the grandeur of its owner.

Villa d'otium is quite another matter. Countryside villas have been specially planned to take full advantage of a picturesque location. Cicero was highly praising the advantages of a country villa,37 the panoramic view from the windows of the villa to the sea was valued even more than the interior. If there was no such view over to the sea (as, for example, in the cramped cities of Pompeii or Herculaneum), the owner of a “domus” tried to compensate as much as possible by luxurious wall paintings imitating landscapes. Such frescoes depicted a parallel reality with wonderful gardens, marble palaces and terraces, exotic animals and plants.

Most important for our research, retreat villas were most suited for inviting guests and visitors, serving as a showcase of wealth, taste and power of their owners, therefore dedicating much attention to public spaces within.

To make the most out of the “pleasantness of location” (amoenitas),38 a series of panoramic rooms overlooking the sea have been provided for in both villas San Marco and Arianna. In the Villa San Marco, there is a luxurious triclinium or “oe-cus” (banquet room). On one side, this room overlooks the edge of the hill with the seashore, while the other side opens into the inner garden (peristyle), framed by columns, with a pool and a fountain in the middle.

Retreat villas, therefore, provided their owners with the opportunity to enjoy the countryside and silence, while at the same time having the basic amenities of a “city life” with baths, rooms for reading, porticoes for walking,39 kitchens with all the necessary equipment to cook any dishes and in any quantity, and – most importantly – enough spaces in which it was possible to spend time with important guests.

-

IV. Why Roman villas were less private and more public?

Life of a Roman was literally “taking place” – because it necessarily had to be a very public matter. Every important operation had to be performed in the presence of a witness – be it a sales or purchase transaction, or another step in the politician’s career. The main venue for public life was a forum in the center of the city – but not only, baths, markets and villas were not less important for public policy than places for political assemblies.40

Since villas were seeing frequent visitors – clients, friends, political partners, its space had to be segregated in several zones. Every room assumed some degree of privacy and public function, thus creating a continuum of spaces differing in a proportion of private and public.

All interior rooms and spaces in the villa were therefore within this continuum. This scale of private morphing into public existed not only as a visual and mental construct but, more powerfully, as a physical reality, created through everyday usage and actualization.

Which sources are most valuable for the study of this continuum? In line with Amy Russel’s “movement, memory and performance” triad, these are narratives by villa owners or their guests recalling visits to villas, in which they moved through various rooms.41 Another example is “travel guides” through villas, where their owners implicitly reveal the inner logic of space, describing the premises.42

On the one side of this continuum there was a private extreme – cubiculum, where no guests were allowed. On the opposite side, there was vestibulum – waiting room in front of the atrium, where clients, slaves and guests gathered every morning, waiting for the master of a house to come out and collect invitations, news or requests.43 The public category also included atrium, triclinium (dining room), tablinum (owner’s office), baths and peristyle (garden).

Most important rooms that played a particularly big role in public proceedings, were often aligned along the central axis. These were: atrium which served as a main transitory space between private and public zones of a villa,44 tablinum, peristyle and triclinium.

In the house of a man who was himself a public figure, a luxurious atrium was regarded in many ways as public space.45

Tablinum (from the word tabula – a waxed tablet for writing with a stylus) was the study of a pater familias . The importance of this room was often emphasized by its location just opposite the entrance to the atrium. Visitors who were entering a villa, were able to catch an impressive view between two columns on either side of the vestibulum: a vertical column of light falling from the complu-vium, behind which was the entrance to the tablinum, in the far end of which an open window into the garden with other wonders.

This alignment of rooms would serve as a natural spectacular perspective, penetrating the most representative and public premises of the villa, and thus leading the gaze into infinity through repeating geometric shapes (similar to baroque effects with mirrors on the opposite walls). This eye-catching perspective must have been powerful enough to impress any visitor, who was thus implicitly motivated to quickly work himself into the owner’s favor and to be received in the hidden and still tantalizingly close parts of the villa.

If space and the owner’s budget allowed, the architects designed the villas so that the maximum number of public spaces was located along this spectacular axis and connected by windows or doors.

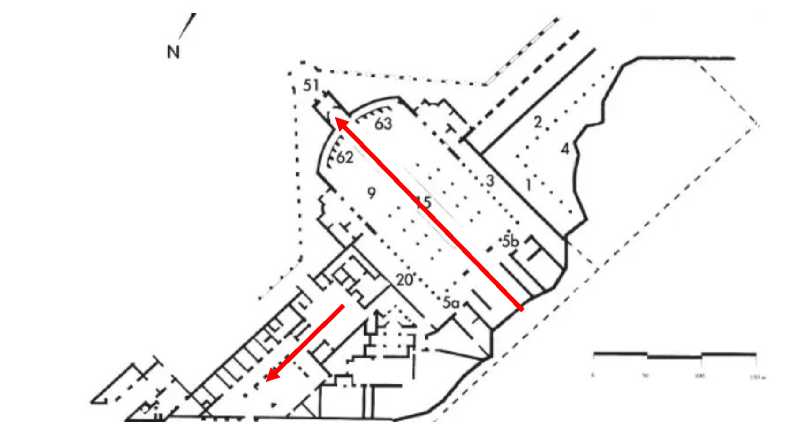

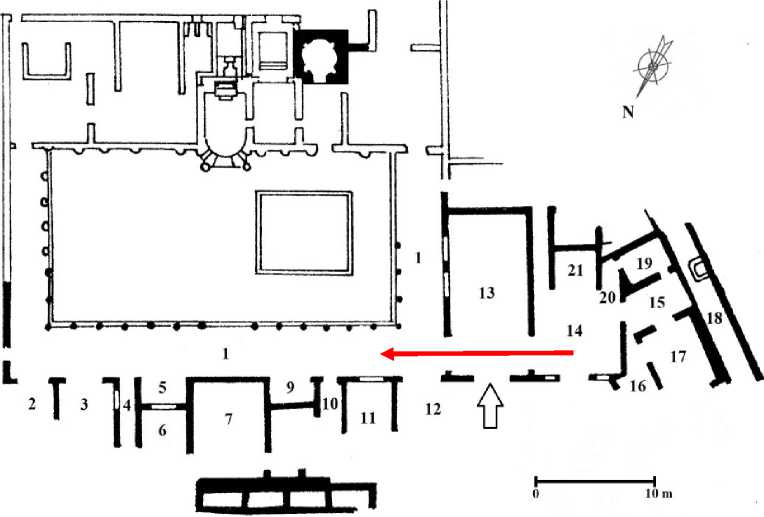

Most luxurious villas tend to keep as much of this axis as possible – Villa San Marco boasted two such axes. One at the entrance: it united atrium, tablinum and the smaller peristyle. Due to the difficult terrain and the positioning of a villa next to the steep slope to the south the main axis of the complex stretched from south to north, but the access was from the west. Another restriction was set by the Stabiae’s city walls to the north. Due to all these challenges, the perspective was not developed into the full sequence. For example, tablinum in the Villa San Marco was shifted to the right from the vestibulum-atrium axis.

Fig. 2. Villa San-Marco, Stabia

The second axis was organized around a luxurious oecus on the edge of the cliff. Through the opposite wall, guests could see the whole peristyle up to the nimphaeum at its far end.

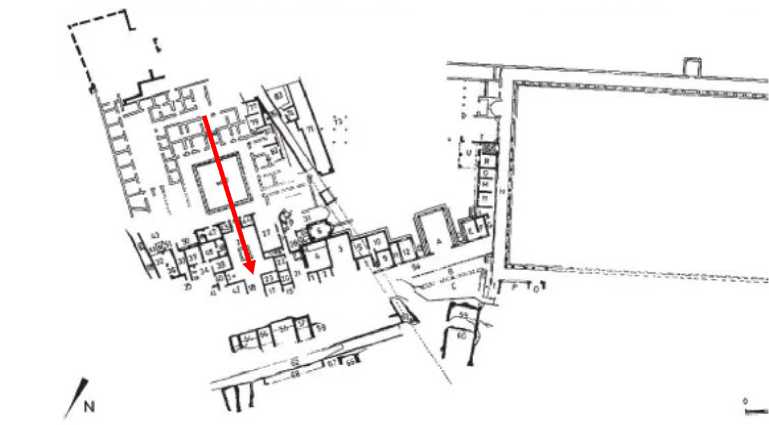

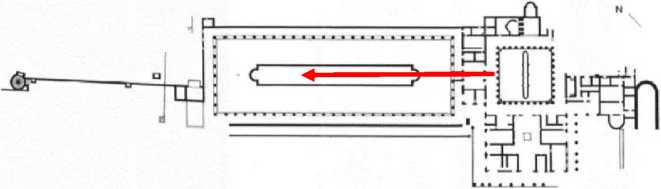

In villa Arianna the axis united an older, smaller peristyle and a tuscan atrium.

Fig. 3. Villa Arianna A, Stabia

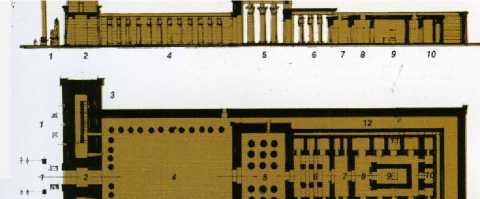

In the Villa Arianna, Second Complex, a big dining hall, oecus (No. 13 – Fig. 4) was opening into both peristyle (No. 1 – Fig. 4) and a room, while the layout of the place dictated a third opening into the terrace facing the sea.

Fig. 4. Villa Arianna, Second Complex46

46 Gardelli, Butyagin, Giordano, Squillante 2017, 164.

In the Villa of the Papyri thanks to an abundance of available space the axis united both peristyles.

Fig. 5. Herculaneum – Villa of the Papyri

Such a longitudinal axis that structured public-private continuum was present in most of the villas where there was enough space and the landscape allowed for such layout.

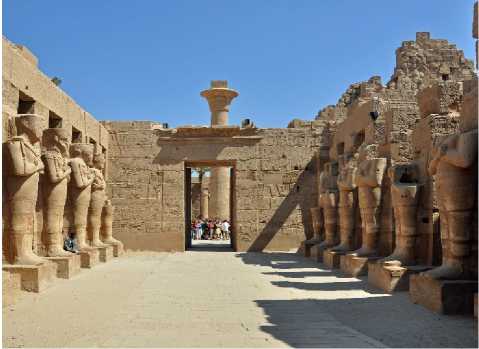

The first examples of such axis intentionally utilized in the architecture are present in Egyptian temples of the Middle and the New Kingdom. Below you can see a longitudinal axis in the Karnak temple complex (see next page).

This perspective presumably served as a powerful tool for leading a visitor through a series of transitional spaces in order to reach the sacred interior of the temple. An intricate interplay of light and shadow from the columns must have intensified this effect on a laic.

In Rome, private houses were like fortresses, and public buildings were like hospitable spaces – with inviting porticoes on all sides of the forum, and wide streets leading to it. To put it in the terms of mainstream psychology, Roman houses and villas were architectural introverts, turned inward into themselves. From the street, the houses looked like impregnable fortresses with narrow windows or without them.

The spacious atrium was the center of life at home – here daily rituals were performed on the lararium (home altar). Here, through the compluvium (a hole in the roof), light and rainwater fell inside the house. The light illuminated the atrium and the neighboring rooms.

Random petitioners and strangers could not go beyond the vestibulum or atrium. Acquaintances and friends could end in triclinium, tablinum or thermae (on a big party for many people). And only the closest friends could walk with the owner in the shady silence of the peristyle or in a later and more luxurious space for walks, cryptoporticus.47 M. Zarmakoupi showed in her article, that cryptopor-ticus were often used to connect different public sectors of the villa.48 In light of the argument of this article, such corridors could serve as a means of channeling guests around more private zones, in order to sustain the overall balance of public and private inside a villa. Or even distributing guests into several flows,49 varying in the degree of the vicinity to the master of a villa.

An artists’ reconstruction of an atrium opening into a peristyle

A typical baroque enfilade, the heir to the Roman longitudinal axis, that stressed the idea of eternity and sustainability of the absolutist regimes

Before the dinner (cena)50 or (less commonly) after it guests could go to baths to socialize.51 Even in emergency situations like the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE, Pliny the Elder decided to stick to the traditions and first go to baths at his friend’s villa in Stabiae.52

There was an internal logic in a bath complex. It should not surprise us, because this was still another venue for socializing. The guests would go through this sequence of cold, warm, hot and very hot rooms together (frigidarium, tepidarium, caldarium, laconicum).53 In some or all of these spaces the bather was invited to participate in true communal bathing, not in individual hip baths on the Greek model, but in shared basins of cold or heated water (called alvei or solia).54

Such a predefined route necessitated sustained close contact over a prolonged period with other bathers. By the 2nd century BC, this sequence became systematic and routine,55 which made it a powerful ritual to be used in socializing.

As G. Fagan appropriately puts it, the ubiquity of the bathhouse from the first century BC well into the Byzantine era, marks it as one of the central loci of social contact in the Roman world.56 A keen analysis by the same author of a fragment in Cicero’s speech Pro Caelio shows that roman baths were a ubiquitous feature in every Roman city, familiar to the elite without further precision and that they were an absolutely normal venue for social intercourse,57 where privileged men might be seen together with slaves.58

Being a place where people of different classes interacted, public baths might be therefore compared to those parts of a villa, which could be visited by slaves of other masters (vestibulum, atrium) and by visitors of all kinds (vestibulum, atrium, tablinum, triclinium, peristyle). Even if a wealthy man had his own private bath, he did not hesitate to use a public bath in order to save time or money for heating up his own thermal complex.59 Following the venerated tradition of Cato the Elder60 and Piso Frugi,61 roman landowners were always practical and costconscious.

To conclude, a day of a Roman can be generally seen as a progression from openness and public accessibility to increased privacy and higher exclusiveness in contacts.

The morning started with receiving all kinds of visitors at the entrance (ves-tibulum) – here everyone could address the owner of the villa. Relatively open accessibility characterized routine walk through the forum, where a Roman could be stopped by a passer-by and addressed in some way or another. However, some restrictions could be imposed here – a man in a hurry could refuse personal contact (slave retinues and lictors of a wealthy Roman served as a filter for any unwanted conversation out in the streets).62 A visit to the baths usually followed the busy day in the forum, which, in Garrett Fagan’s words, “marked the transition from relatively open accessibility in the forum to more limited accessibility at the dinner party, which was populated by invited guests only.”63

Another interesting element is a specific decoration that underlined and fostered movement along the aforementioned continuum. In her article about cryptoportici Mantha Zarmakoupi made a curious assumption about the so-called zebra stripe decoration in the peristyle and cryptoporticus in villa Oplontis.64 Previously it was considered as a marker of a service/servile area of a villa. This design was used in the rooms of public buildings with much traffic (the corridor in the Stabian Baths and the passageways of the amphitheater in Pompeii). As M. Zarmakoupi appropriately puts it, “the zebra patterns were probably meant to create an eye-catching and repeating design that would encourage movement in the more public areas of a house rather than signifying the service areas”.65

The author then concludes that such patterns could provide a unified style of decoration that would easily guide a visitor on his route towards another public space of the villa. In the case of villa Oplontis, visitors would have been led through peristyle and into the cryptoporticus where they might sit on the benches, waiting to be received by the owner. Their view would have been directed through the zebra patterns through the opening of the porticus onto the pool and garden complex.66

If this was the case, such dynamic decoration might be the first predecessor of the modern lines and stripes on the floors and walls, channeling visitors of hospitals, airports and other big public buildings.

Do we know any names of the owners of the six identified Stabian (or, more generally, Vesuvian) villas? Ancient sources have brought to us the names of two owners of the local villas. Their names are Marcus Marius Gratidianus and Pom-ponianus. Marcus Marius was a friend of Cicero and his villa was located in the Vesuvian area. In one of the letters, Cicero is praising the beauty of the place where his friend lives: “Indeed, you could wonderfully enjoy your leisure time, since you stay in this pleasant place (...) I greatly praise and approve of you and your way of life…For I doubt not that in that study of yours, from which you have opened a window into the Stabian waters of the bay, and obtained a view of Misenum, you have spent the morning hours of those days in light reading”.67

Pomponianus is mentioned by Pliny the Younger in a letter to Tacitus,68 where he describes the heroic death of his uncle, Pliny the Elder. At that time the famous ancient author and naturalist commanded the Roman fleet at Misenum.69 At the onset of the historical eruption on October 24/2570 he tried to evacuate locals by ships (probably from Herculaneum).71

He could not approach the shore near Vesuvius and so went further south. There can be only one place where he could be headed – Stabiae with its villas. Later this day he and his host Pomponianus ran the risk of being blocked inside the villa by a huge layer of ashes. Having escaped from the villa whose walls started to crumble, Pliny the Elder died at the beach of suffocation. Studies have shown that the damage area from a disastrous eruption of Vesuvius could extend as far to the south as Stabiae which is approximately 15 km from the volcano. Sur-rentum is further away and therefore less vulnerable (it is not included in the danger zone by Italy’s civil protection plans in case of an explosive eruption72).

V. Next steps

An important part of the study will be represented by the analysis of the public and private spaces within a roman suburban and country-side villa, which served as an efficient arena for political communication and exchange. This will be done according to the aforementioned approaches and microcontext analysis of literary evidence, as well as archaeological data, mostly from the Vesuvian area.73

It is important to unite the study of the literary and archaeology sources and the methodology. A study of the transformation of spatial notions along the spectrum of private and public must inevitably rest on two pillars – literary evidence that describes people’s “memories and performance”, to use Amy Russel’s scheme, and archaeology, which helps to track “the movement aspect”, which sets “users” of space into the physically determined background by architectural elements.

Gracchan reforms of Roman society were the most important attempt to overcome the crisis of the 2nd century BCE. Although seemingly a failure, the Grac-chan legislation and its consequences had far-reaching effects expressed in the irreversible transformation of many concepts, mental attitudes and processes associated with the “private-public” opposition. As a result, the interpretations of the main concepts – such as public land, private and public property, roads etc. – have experienced a profound change.74 Modern sociology sees a strong link between the privatization of public space and reinforcement of existing patterns of segregation,75 which decreases opportunities for political conversation between social groups and makes it easier for a political system, based on “divide et im-pera”, to establish itself – this is well in line with the political transformation of the Republic into Early Empire.

Another important consideration to be elaborated further is that according to the archaeological evidence the central role of the atrium in public life of a retreat villa has been progressively replaced by large peristyles during the first century BCE. This is in line with the overall hellenization of the Roman mindset and architectural habits.76 Over time these became the real centers of the villa activities. All the rooms around the peristyles are getting equipped with large windows, opening into vistas and enfilades. This article is the first step in the research project, within which I plan to elaborate on the issue of the private/public dichotomy.

Список литературы Architectural perspective and the private-public continuum in the villas of ancient Stabiae: preliminary considerations

- Acconci, V. (1990) “Public Space, Private Time,” Critical Inquiry, 16.4, 900-918.

- Anderson, J. C. jr. (1997) Roman Architecture and Society. Baltimore, London: Johns Hop- kins University Press.

- Arendt, H. (1958) The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bailey, J. (2002) “From Public to Private: The Development of the Concept of the "Pri- vate," Social Research 69.1, Privacy in Post-Communist Europe, 15-31.

- Bobbio, N. (1989) “The Great Dichotomy: Public/Private,” in Democracy and Dictatorship: The Nature and Limits of State Power. Oxford: Polity, 1-21.

- Bourdieu, P. (1991). “Lecture "About the State" from November 21, 1991,” in: Lectures at the College de France.

- Clarke, J. R. (1991) The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C–A.D. 250: Ritual, Space, and Decora- tion. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Court, S., Rainer, L. (2020) Herculaneum and the House of the Bicentenary: History and Heritage. Los Angeles.

- D'Arms, J. H. (1970) Romans on the Bay of Naples. A Social and Cultural Study of the Villas and their Owners from 150 B.C. to A.D. 400. Cambridge (Mass.), Harvard University Press.

- D'Arms, J. H. (1974) “Puteoli in the Second Century of the Roman Empire: A Social and Economic Study,” The Journal of Roman Studies 64, 104–124.

- Fagan, G. G. (2011) “Socializing at the Baths,” The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 358-373.

- Favro, D.G. (1996) The Urban Image of Augustan Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gardelli, P. (2017) “History of the Excavations in the Area of the Great Peristyle of the Villa Arianna:18th Century Explorations to the Latest Investigations,” in The Exca- vation and Study of the Garden of the Great Peristyle of the Villa Arianna, Stabiae, 2007-2012. Quaderni di Studi Pompeiani, vol. VII (2016), Castellammare di Stabia, 17-20.

- Gardelli, P. (2019) “Reconstruction and Restoration Works at Villa Arianna in Stabia Prior to the Eruption of 79 A.D.,” in Art of the Ancient World (Iskusstvo Drevnego mira). Vol. 9, 145-162.

- Gardelli, P. (2016) “Stabiae and the Beginning of European Archaeology: from Looting to Science,” in Actual Problems of Theory and History of Art VII, Saint Petersburg, 681– 690.

- Gardelli, P., Barker, S., Fant C. (2016) “Resti pavimentali in opus sectile nel tepidarium e nel caldarium di Villa Arianna a Stabiae,” in Atti del XXI Colloquio Associazione Italiana per lo Studio la Conservazione del Mosaico, Tivoli, 439-448.

- Gardelli, P., Butyagin, A. (2018) “Villa Arianna, Stabiae: interventi di pulitura, scavo e restauro nell’ambiente 71 e nell’area esterna 73 condotti dal Museo Ermitage di San Pietroburgo,” in Rivista di Studi Pompeiani XXIX, 213-218 Gardelli, P., Butyagin, A., Giordano, L., Squillante, T. (2017) “Stabiae. Secondo Complesso, Oecus 13: gli interventi di restauro degli apparati decorativi parietali di tardo Terzo Stile promossi dalMuseo Statale Ermitage di San Pietroburgo,” in Rivista di Studi Pompeiani XXVIII, 164-167.

- Hillier, B. and Hanson, J. (1984) The Social Logic of Space. Cambridge: Cambridge Univer- sity Press.

- Kohn, M. (2004) Brave New Neighborhoods. The Privatization of Public Space. New York: Routledge.

- Landes, J. B. (ed.) (1998) Feminism, the Public and the Private. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Laurence, R. and Wallace-Hadrill, A. (eds.) (1997). “Domestic Space in the Roman World: Pompeii and Beyond,” in Journal of Roman Archaeology Suppl. 22. Portsmouth.

- Marzano, A. (2007) Roman Villas in Central Italy: A Social and Economic History. Boston: Brill.

- Marzano, A., Métraux, G.P.R. (2018) The Roman Villa in the Mediterranean Basin (Late Republic to Late Antiquity). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mattusch, C., Lie, H. (2005) The Villa Dei Papiri at Herculaneum: Life and Afterlife of a Sculpture Collection. Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

- Milnor, K. (2005) Gender, Domesticity and the Age of Augustus: Inventing Private Life. Ox- ford: Oxford University Press.

- Parsons, S. (2008). “Public/Private Tensions in the Photography of Sally Mann,” in History of Photography, 123-136.

- Pateman, C. (1983) “Feminist critiques of the public/private dichotomy,” in Benn and Gaus (eds.), Public and Private in Social Life. London: Croom Helm, 281–303.

- Penner, B., Borden, I. and Rendell, J., eds. (2000) Gender Space Architecture: An Interdis- ciplinary Introduction. London: Routledge.

- Pitkin, H. (1981) “Justice: On Relating Private and Public,” Political Theory 9.3, 327–352.

- Riggsby, A. M. (1997) ‘“Public” and “private” in Roman culture,” Journal of Roman Archae- ology 10, 36–56.

- Russel, A. (2016) The Politics of Public Space in Republican Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sennett, R. (1976) The Fall of Public Man. New York: Random House.

- Smith, J. (1998) Roman Villas: A Study in Social Structure. London: Routledge.

- Squires, J. (2003) “Public and Private,” in Political concepts. Manchester: Manchester Uni- versity Press, 131-144.

- Telminov, V. (2018) The Reformation Activities of Gaius Gracchus: Problems of Reconstruc- tion and the Social Consequences for the Roman Civitas (Ph.D. thesis). Russian State University for Humanities (Moscow).

- Wallace-Hadrill, A. (2011) Herculaneum, Past and Future. London.

- Wallace-Hadrill, A. (2012) “Inscriptions in the Private Spaces,” in Inscriptions in the Pri- vate Sphere in the Greco-Roman World, 1-10.

- Weintraub, J., Kumar, K. (1997) Public and Private in Thought and Practice: Perspectives on a Grand Dichotomy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Winterling, A. (2005) “Öffentlich” und “privat” im kaiserzeitlichen Rom,” in Schmitt, T., W. Schmitz, and A. Winterling, hrsgs. Gegenwärtige Antike – antike Gegenwarten. Kolloquium zum 60. Geburtstag von Rolf Rilinger. Munich: R. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 223–44.

- Zaccaria Ruggiu, A. (1995) Spazio privato e spazio pubblico nella città romana. Collection de l’École française de Rome. Rome: École française de Rome.

- Zarmakoupi, M. (2011) “Porticus and cryptoporticus in luxury villa architecture,” in Art, industry and infrastructurein Roman Pompeii. Ed. by E. Poehler, M. Flohr and K. Cole. Oxford, 50-61.