Artifacts from the Ural-Hungarian center (800–1000 ad), recently found at Ob Ugrian sanctuaries

Автор: Baulo A.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.51, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article introduces four silver dishes and a copper plaque from Ob Ugrian sanctuaries in the Yamal-Nenets and Khanty-Mansi (Yugra) Autonomous Okrugs. A dish representing a bird snatching a fi sh; a dish and a plaque representing deer; a medallion of a dish showing a griffi n and two fl ying birds; and a dish (sliced into pieces) with a scene of a wedding feast were apparently manufactured at the Ural-Hungarian center in the 9th or 10th century. Parallels from medieval workshops of Iran and Central Asia are listed. In terms of technology and ornamentation, seven artifacts from the Ural-Hungarian center can be regarded as a separate subgroup. Each is made from three superimposed silver sheets without gilding and has a thin punched ornamentation on the face (its negative image is clearly visible on the reverse side). The ornamentation includes a border consisting of two parallel arches and a vertical dash with three round imprints of a punch, arranged in a pyramid, and a punch imprint on the animal’s paw. Both humans and animals have large almond-shaped eyes with iris but no pupil. A dish with a scratched drawing superimposed on the principal composition is the fi rst known example of such an item among the Ural-Hungarian artifacts. An explanation is provided as to why those artifacts survived in the ritual practice of Ob Ugrians, and ways they could be used in the ritual are suggested.

Ural-hungarian center, silver, dish, deer, horseman, griffin

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146876

IDR: 145146876 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2023.51.2.110-119

Текст научной статьи Artifacts from the Ural-Hungarian center (800–1000 ad), recently found at Ob Ugrian sanctuaries

Over the past half century, the north of Western Siberia has acquired the status of a treasury of silver vessels from Iran, Central Asia, Byzantium, Volga Bulgaria, Europe, etc., which ended up on this territory in the Middle Ages (see, e.g., (Sokrovishcha Priobya, 1996; Sokrovishcha Priobya…, 2003; Baulo, 2002; Fedorova, 2019; and others)). Noteworthy are several silver vessels that B.I. Marshak originally attributed to an early Magyar group (Sokrovishcha Priobya, 1996: No. 53–55). According to the researcher, there was a manufacturing center in Eastern Europe, whose products were similar in style to those of both the late Sogdian craftsmen of the early 9th century, and the Magyar people of the late 9th–10th centuries. Although, items of the early Magyar group were not found on the territory of Hungary (“country of Atelkuz”), where the Magyars came in the last years of the 9th century, nor along the path of their resettlement in the 8th–9th centuries (Marshak, 1996: 16). N.V. Fedorova, having studied all such items, known in the early 21st century, and places of their discovery, suggested that these were the products of Hungarian masters of “Great Hungary” (or original Hungary, which was associated by Eastern geographers with the country of the Bashkirs), i.e. Ural centers of Hungarian settlement before their resettlement to Europe (2003: 141–144).

The items discovered in the early 21st century at the sanctuaries of the Khanty people in the Shuryshkarsky District of the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug (YaNAO), in particular a large dish representing an eagle owl standing on the back of a deer, became additional evidence in favor of the Ural localization of the Hungarian group of silver dishes. It became clear that these were not the products of Danubian Hungary, and that the iconography and style of these vessels combined the features of the emerging art of the Eastern European nomadic Hungarians, the old Ural tradition of their ancestors, and the toreutics of the Abbasid Caliphate and the Samanid state (Baulo, Marshak, Fedorova, 2004). The masters of this center followed the traditions of Central Asia. As samples, they chose the Sogdian and Khorasan vessels from the collection of their workshops, and then developed and varied the motifs of their ornamentation. Some images and ornaments on the products of this center find parallels among Central Asian and Iranian artifacts of the 10th century (Marshak, 1996: 16–18). Diagnostic features of products of the Ural-Hungarian center are the following ornamentation elements: a border of two arches, with a dash extending from them; a dash with three dots arranged in a triangle; a punch imprint on the animal’s paw. In addition, the dishes are manufactured using the technique of superimposition of three metal sheets on top of each other.

Prior to the publication of this article, the group of Ural-Hungarian silver products of the 9th–10th centuries consisted of seven silver vessels (Fedorova, 2019: 75). This article is aimed to introduce five items that, according to the above features, can be classified as Ural-Hungarian, as well as to identify vessels of this group made in the same workshop.

Description and attribution of the new finds

In June 2022, the Museum of Nature and Man in Khanty-Mansiysk hosted the opening of the exhibition “Ob Ugrians: Home and Cosmos”, dedicated to the anniversary of the famous ethnographer I.N. Gemuev (1942–2005). During this event, I became acquainted with a man—a representative of one of the families of the Khanty people, living in the Nazym River basin (Khanty-Mansiysky District, Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug-Yugra (KhMAO-Yugra)). He said that his grandfather, who lived in the upper reaches of the Nazym, had some “heirloom antiques”, which, after his death, were taken to an apartment in the city. These turned out to be the items of traditional utensils, made of birch-bark and woolen cloth, as well as ritual items — a silver bowl and a large copper plaque, wrapped in scarves. The man did not know how the things got to his grandfather and how they were used in the ritual sphere, he only told that the bowl and the plaque were kept in a small chest in the sacred corner of the house.

A silver dish (bowl) representing a bird of prey and a fish (Fig. 1, a , b ). The dish is round, with a diameter of 20.5 cm, made by forging from three superimposed metal sheets; its vertical rim is thickened and chased on the lower part of the front surface. There is a thin punched ornamentation on the front surface. Its negative image is clearly visible on the reverse side.

The ornamentation is concentrated in the central medallion. The medallion is round, 11 cm in diameter, surrounded by a border 0.5 cm wide. The border is ornamented with a pattern consisting of two parallel arches, going across it, and a vertical dash, extending from them, with three round imprints of a punch, arranged in a pyramid. The composition consists of two interacting characters: a bird of prey is holding a large fish in its paws.

The body and head of the bird are depicted in profile, the wings are open, and powerful clawed paws hold the fish. Six feathers ornamented with notches descend from each wing. The body is smooth and unornamented. Paws are four-toed, with one toe sharply set aside, and on each paw, there is an imprint of a punch. The tail consists of six feathers, shaded with notches, and is separated from the body by a string of pearls. The eye is round with a pupil; there is a line running from the eye to the right. The beak is bent down, and at its base there is a punch imprint. The lines of the wings at their base and those of the torso are completed with a pattern in the form of three imprints of a punch arranged into a pyramid.

The fish is shown in profile, with its tail and fins highlighted. The scales are rendered as ovals outlined with notches, oriented to the left; inside each oval, there is an additional notch. The eye is indicated by a punch imprint.

On the chest of the bird, there is a barely visible engraved anthropomorphic mask, which is a later addition (Fig. 1, c ). This is the first time when graffiti, made on top of the existing image, was found on the items of the Ural-Hungarian group.

Parallels . A bird of prey is usually shown standing on an animal: on a late Sasanian dish of the 7th–8th centuries, an eagle with spread wings is standing on the back of a fallow deer (Trever, Lukonin, 1987: 116, cat. No. 29); a bird of prey on the back of a gazelle is depicted in the oval medallion of a silver bottle of the 6th–7th centuries, which was discovered near the village of Kurilova, Osinsky Uyezd, Perm Governorate (Ibid.: 116, cat. No. 31), and on a dish of the 7th–8th centuries from a hoard found near the village of Maltseva, Kudymkarsky District, Perm Governorate (Ibid.: 119, cat. No. 41); the plot of “a bird on the back of a deer” is conveyed on a dish of the 10th century from the Tomsk Governorate (Sokrovishcha Priobya…, 2003: Cat. 28), and on a dish of the 9th–10th centuries from

Fig. 1 . Silver dish representing a bird snatching a fish. Ural-Hungarian center, 9th–10th centuries. a – front side; b – reverse side; c – graffiti in the form of a mask on the chest of a bird.

а

the Shuryshkarsky District, YaNAO (Baulo, Marshak, Fedorova, 2004: 108, fig. 1).

Large plaque showing a deer (Fig. 2). Its diameter is 19.5 cm, weight 144 g. This item is made from a forged copper sheet, and is slightly convex. On the edge of the plaque, large round pearls were minted from the reverse side. In the upper part of the plaque, on the reverse side, two large holes were drilled; two other holes, of a smaller diameter, are under the deer antlers. Since no pearls were minted in the zone of large holes, it can be assumed that the four holes were drilled for attaching a handle.

There is thin punched ornamentation on the front surface. Its negative image is clearly visible on the reverse side. The ornamentation is concentrated in the central medallion. The medallion is round, 15.5 cm in diameter, surrounded by a border 0.8 cm wide. The border is decorated with a pattern consisting of arches going across it and three round imprints of a punch, arranged in a pyramid.

Inside the medallion, there is a figure of a deer. The animal, oriented to the left, is shown in profile, possibly in a jump. The antlers have four branches. The outlines, proportions of the body, the short tail correspond to the real prototype; the hind legs are brought together, the front legs are forked, with the right leg raised up. The cloven hooves are disproportionately long. There is a small vertical outgrowth protruding out of the middle of the belly line. A fruit or flower bud is hanging from the deer’s mouth.

In the lower part of the medallion, from the border, a palmetto-shaped flower is rising on a stem; its upper petals are ornamented with a pattern in the form of three circles on a short stem. Such a floral motif is typical of toreutics in the eastern regions of Central Asia in the 8th– 9th centuries (Darkevich, 1976: 87).

Parallels. The ornamentation of the edge with a strip of pearls minted on the reverse side is typical of round forged silver West Siberian plaques of the 10th– 12th centuries (see, e.g., (Spitsyn, 1906: Fig. 53, p. 32; Chernetsov, 1957: 243; Baulo, 2011: 124, 243–244; and others)). Similar pearls adorn a bronze cast plaque of the 10th–11th centuries, with the figure of an eagle owl, found in the burial 73 at the Saigatinsky VI cemetery (Drevniye bronzy Obi…, 2000: Cat. No. 28), which is identical to the image of an owl on a Voikary dish

Fig. 2. Copper plaque representing a deer. Ural-Hungarian center, 9th–10th centuries. a – photograph; b – trace-drawing.

(Baulo, Marshak, Fedorova, 2004: 108, fig. 1), and a plaque from the 9th–10th centuries, with images of a bear, a fish, and two snakes, from the basin of the Konda River (Baulo, 2013: Fig. 4). On the described plaque with a deer, the pearls along the edge of the item may have been a later addition; the edge of a silver plaque of the 9th–10th centuries from the Konda cemetery was finished in a similar way (Ibid.: Fig. 1).

Silver dish representing a deer (Fig. 3). The dish is stored in the Khanty people camp in the basin of the Okhlym River (Khanty-Mansiysky District of KhMAO-Yugra). Diameter is 19 cm. The dish is forged from three superimposed metal sheets. The vertical rim is thickened, embossed on the lower part of the front surface. There is thin punched ornamentation on the front surface. Its negative image is clearly visible on the reverse side. A small hole is drilled under the rim.

The ornamentation is concentrated in the central medallion. The medallion is round, 12 cm in diameter, surrounded by a border 0.5 cm wide. The border is ornamented with a pattern of two parallel arches going across it.

The figure of a deer is situated within the borders of the medallion, while three branches of the antlers overlap the border, which suggests that the deer was depicted first, and then the lines of the border were drawn around it. The animal is shown in profile, moving to the left. Antlers have six branches. Large oval eyes are without pupils. On the torso, ribs are marked by two boat-shaped lines. A fruit or flower bud is hanging from the deer’s mouth. The outlines, proportions of the body, the short tail, and the hooves correspond to the real prototype.

Fig. 3. Silver dish representing a deer. Ural-Hungarian center, 9th–10th centuries.

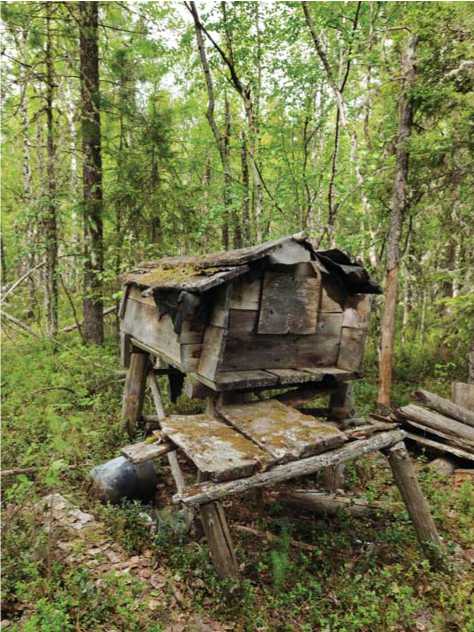

The medallion of the silver dish. It is kept in a chest in a sacred shed of the Kazym Khanty as an offering (Fig. 4). The item is cut from a large dish, the medallion’s diameter is 14 cm, the width of the border is 0.6 cm (Fig. 5). The border is ornamented with a pattern consisting of arches going across it and three imprints of a punch, arranged in a pyramid. There is thin punched ornamentation on the front surface. Its negative image is clearly visible on the reverse side.

Fig. 4. Sacred shed of the Khanty people.

The central place in the composition is taken by the figure of a griffin, with flying ducks depicted above and below it.

The griffin—a mythical beast with the body of a lion and the head of an eagle—is shown in profile, walking to the left. He has a massive body and powerful clawed paws. On each paw, there is a punch imprint. The upturned tail, with a palmette-shaped tassel, is decorated with a wavy line. The lines of the belly and paws have hatching strokes, possibly showing the fur; the lines at the base of the left paws and the lower line of the head end in a pattern of three imprints of a punch, arranged in a pyramid. The lines of the upper wing and ribs are decorated in the same manner. In the middle of the belly line, there is a small vertical outgrowth protruding out. Lines of the ribs are rendered schematically. On the neck, in the center of the torso, there is an ornament in the form of three round imprints of a punch, arranged in a pyramid. On the back, there are two wings of six feathers each, shaded with hatching strokes. The griffin has a small head, which is not proportional to the massive body, the beak bent down (with a punch imprint at its base), and the ear shown at the top of the head. The eye is almond-shaped, with a pupil.

The ducks are shown in profile, in flight towards the viewer. The beak is elongated, rectangular in shape.

The long neck is stretched out and shaded with hatching strokes, the wing is raised, the foot is tucked under the stomach. The wing and tail of the upper bird show five feathers each; those of the lower bird, four feathers; all feathers are ornamented with short notches. On a smoothly outlined foot, pressed to the stomach, there is an imprint of a round punch.

Parallels . The images of the Senmurv (Simurgh?), very close to the griffin, are known on Iranian and Sogdian

Fig. 5. Medallion of the silver dish representing a griffin and flying birds. Ural-Hungarian center, 9th–10th centuries.

a – photograph; b – trace-drawing.

silver vessels of the 7th–8th centuries (Darkevich, 1976: 64, fig. 4; tab. 5, 3 ; Marshak, 1971: 21, 22). Griffins are depicted on two golden vessels of the 7th century from the Nagy Szent Miklos treasure (the territory of modern Romania): a single image of a griffin is on a bowl with a buckle, a griffin tormenting a deer is on one of the medallions on a jug. The treasure itself has long been a subject of controversy: it could have been buried by the ancient Bulgarians or Avars; the vessels therein were possibly made by the Khazars. Many researchers are of the opinion that the owners of the treasure vessels in the 10th–11th centuries were Hungarians (The Gold of the Avars…, 2002: 17, No. 2; p. 40, No. 20; p. 59–61). In Sogdian art, noteworthy are the murals of the 7th century that adorned the palace in Varakhsha: a warrior and an elephant rider are fighting off griffins; one of the halls was called the “Gryphons Hall” due to its décor (it dates back to about the 7th–8th centuries) (Dyakonov, 1954: 93, fig. 2; p. 142–143, fig. 14).

In the Bolshiye Tigany cemetery of the 9th century (Alekseevsky District, Republic of Tatarstan), which is attributed to one of the groups of early Hungarians who lived on the left bank in the lower reaches of the Kama River, belt plaques were found, bearing the images of Senmurv dogs, according to the definition of the authors of the excavations (Finno-Ugry…, 1987: 238, 239; 352, fig. 9); these creatures also resemble young lions with wings and bird’s heads, i.e. griffins. In the village of Lopkhari, Shuryshkarsky District, YaNAO, a hoard included a large silver bowl showing a scene of Alexander flying on griffins (Byzantium, late 12th to early 13th centuries) (Sokrovishcha Priobya, 1996: Cat. 69). A hoard discovered in the Tazovsky District, YaNAO, contains a large silver plaque with a figure of a griffin (diameter 12 cm; stored in the collections of the Tazovsky Regional Museum of Local Lore) (Fig. 6).

The image of a griffin on a dish from the shed of the Kyzym Khanty, in contrast to the graceful lion-shaped figures in the art of Iran and Sogd, is massive. Filling the order, the master was most likely guided by the figure of a bull—an animal that he could actually see in real life.

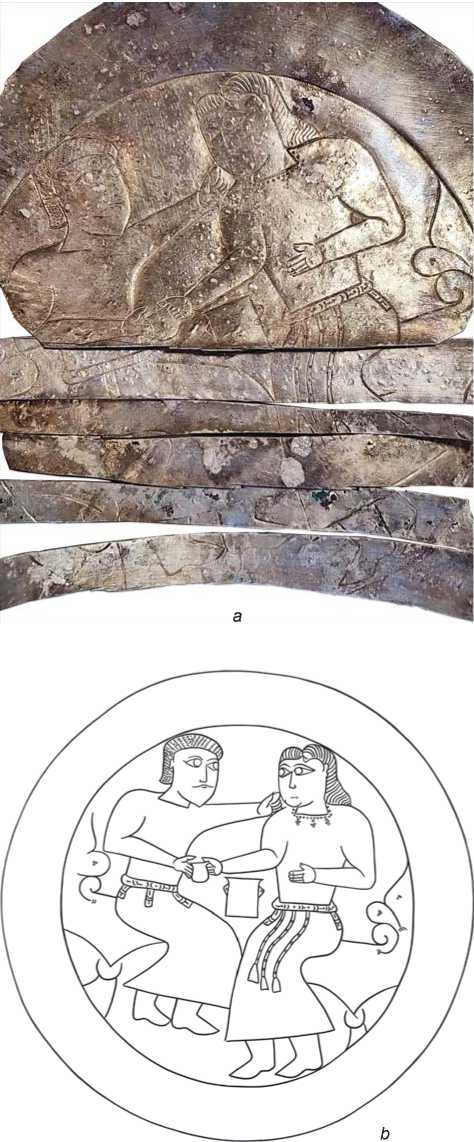

Silver dish sliced into pieces (Fig. 7). A large fragment of the upper part of the bowl and five narrow pieces have been preserved. According to the information received from local residents, the pieces were sewn onto the fur clothes of a person interred in an unknown burial ground in the Priuralsky District of the YaNAO.

The original diameter of the find was 26 cm, that of the medallion 20 cm. There is thin punched ornamentation on the face.

The medallion contains a composition of a man and a woman sitting in armchairs opposite each other; between them, there is a rectangular vessel for the wine (?), with two handles. The woman is passing with her right hand a mug with a rounded bottom to the man, and he is

Fig. 6 . Silver plaque representing a griffin.

reaching for her head with his left hand, probably trying to hug her. A fragment of a wall painting in Panjakent (object XVI, room 10) shows that the Sogdians of the Early Middle Ages held mugs for wine in their hands with the help of a special shield-guard attached to the top of the handle, where the thumb was located (Marshak, 2017: 503, fig. 21).

The faces of the characters are oval, and their long eyebrows are located parallel to the upper contour of large almond-shaped eyes with iris but no pupil.

The line of a straight nose stretches from the inner corners of the eyes; the mouths of the characters are small; and the man has a short mustache. The woman has a semicircular chin, and the man has a wedge-shaped one— perhaps, a small beard is conventionally conveyed in this way. The man’s hair is short, shown with lines above the forehead, with dots on the back of the head; the small right ear is visible. The woman’s hair is rendered in two shaded waves; the small left ear is visible. Hands show marked nails.

The both characters are wearing long shirts. Pointy boots with heels are visible from under the hem of the shirts. Shirts are with narrow neck openings, without collars, and with long narrow sleeves. The collar of the woman’s shirt is decorated with embroidery or sewed-on pieces. Narrow belts are ornamented with a pattern of two transverse parallel arches, from which a dash with a dot is extending. From the belts, short rectangular strips are hanging, designed in the same way as the belts. Possibly, these show hangers for a sheath of a sword or dagger of the man. The woman is depicted with three long narrow cords, with bellshaped pendants, hanging from her belt; the cords are ornamented with small circles.

Fig. 7 . Silver dish sliced into pieces. Ural-Hungarian center, 9th–10th centuries.

a – photograph; b – trace-drawing.

The dish was preserved in the form of pieces; therefore, it is impossible to describe the armchairs in detail; their backs are ornamented with a pattern in the form of palmettes (inside them, there are patterns of three

round imprints of a punch, arranged in a pyramid), and the legs of the armchairs are depicted as columns inserted into the balls.

Parallels. Cut silver bowls are known in the materials from medieval sites. Among them, there are pieces of the central medallion of a dish representing a horseman (Ural-Hungarian center, 9th century), which presumably comes from the Kheto-se cemetery in the south of the Yamal Peninsula (Sokrovishcha Priobya…, 2003: Cat. 22). Another example is the medallion sliced into pieces from a cup of the 9th–10th centuries, with an image of a man and a woman, found in the upper reaches of the Konda River (Sovietsky District, KhMAO-Yugra): the burial contained the remains of the deceased, dressed in a fur coat; on top of the coat, in the area of the chest, silver pieces were evenly laid face down (Baulo, 2013).

Belts with pendants on laces are the elements of women’s clothing, shown on a jug with images of musicians and on a silver dish with a scene of a royal feast. B.I. Marshak identified the both vessels as Sogdian items and dated them to the 8th–9th centuries (1971: 23, 91, 92), and V.P. Darkevich attributed them to the products of Eastern Iran of the second half of the 8th to the first half of the 9th century (1976: 40, 41; tab. VI, 4 ; VII, 4 ). Belts in the form of a narrow strip with three hanging straps are known from the frescoes of Samarra (Iraq) and Lashkari Bazar (Afghanistan); similar belts are represented on two characters shown on the ladle of the 11th century, found near the village of Shuryshkaryh (Sokrovishcha Priobya, 1996: 85–89), and on a man depicted on a Konda silver plaque of the 9th–10th centuries (Baulo, 2013: Fig. 1).

The table scene is depicted on the outside of a silver bowl (Northern Tokharistan (?), 6th–7th centuries) found in the Perm Territory: a woman on the left and a man on the right, with a glass raised in his hand, are sitting in the lotus position (Marshak, 2017: 496, fig. 16). At the bottom of a silver bowl found in Kustanai (Kazakhstan) (Tokharistan or the lands to the south of it, 4th–5th centuries), with scenes from the tragedies of Euripides, a man is depicted sitting on the left and a woman on the right (Ibid.: 498, fig. 18). In the 7th–8th centuries mural on the southern wall (object XXIV) in Penjikent, a feast scene is shown: a man and a woman are sitting opposite each other on a long bench, each holding an ornamentated rhyton in the hand (Srednyaya Aziya…, 1999: Pl. 33, 4 ). In the murals of Panjakent, A.M. Belenitsky identified illustrations to the legend of Rostam (room VI/41) from the poem Shahnameh (“The Book of Kings”) by Ferdowsi (1973: 47, 48). It can be assumed that the well-known plot of this poem is reproduced on our bowl: “Rostam marries the daughter of Shah Samangan—Takhmina”.

Thus, all the previously mentioned features of toreutics allow the unambiguous attribution of the introduced artifacts to the production of the Ural-Hungarian center of the 9th–10th centuries.

On identification of a group of products of the Ural-Hungarian center made in the same workshop

Today, already 12 products of the Ural-Hungarian center are known, 11 of which are made of silver, and one of copper*. These are dishes representing the following: a horseman with a spear—from the territory of the YaNAO (Sokrovishcha Priobya…, 2003: Cat. 19), a lion—from the village of Kudesova, Cherdynsky Uyezd (Ibid.: Cat. 20), a rider in armor—from the village of Muzhi (Ibid.: Cat. 21), a horseman with a bird of prey—from the Heto-se burial ground (Ibid.: Cat. 22), a horseman with a bird of prey and a servant—from the Utemilsky settlement in Vyatsky Uyezd (Darkevich, 1976: Pl. 56, 4 ), an eagle owl on a deer (Baulo, Marshak, Fedorova, 2004: Fig. 1), a rider and a lion (Ibid.: Fig. 3) (the last two are from the Voikar River basin, Shuryshkarsky District, YaNAO), as well as five items described in this article. Geographically, the products are divided into two groups: two dishes from the Kama region, and the rest from the territory of the YaNAO and KhMAO-Yugra. Four bowls are made with gilding, the others show no signs of gilding.

Notably, the subjects depicted on the vessels of this group date back to the art of Iran and Central Asia (Marshak, 1996: 16–18); they do not have any Siberian specificity. Consequently, the products that ended up in the north of Western Siberia were not custom made for the local nobility; they were ordinary workshop products that were exported as part of some kind of exchange relations.

An analysis of the main details of all the 12 finds makes it possible to combine five items published for the first time, and two Voikar dishes (with an eagle owl standing on a deer, and with a rider killing a lion (Baulo, Marshak, Fedorova, 2004)) into a subgroup of products of the Ural-Hungarian center. With a reasonable degree of certainty, the products of this subgroup can be attributed to one workshop. The main features of this subgroup are as follows (see Table ):

technological— the items are made of three superimposed silver sheets**, without gilding; the vertical rim is thickened, and embossed on the lower part on the front surface; thin punched ornamentation is made on the front surface; its negative image is clearly visible on the reverse side;

ornamental— the pattern on the border consists of two parallel arches going across it, and a vertical dash extending from them, with three round imprints of a punch, arranged in a pyramid; completing the line with a pattern of three imprints of a punch, arranged in a pyramid; a punch imprint on the animal’s paw; a punch imprint at the base of the beak; vertical outgrowth on the belly line; decoration of the tail feathers and wings with hatching strokes; long cloven hooves; large, almondshaped eyes with iris but no pupil, in humans and animals. The silver dish showing a figure of a deer, from the basin of the Okhlym River, has the fewest details typical for the Ural-Hungarian artifacts.

Conclusions

The publication of five new items made it possible not only to add to the list of known products of the Ural-Hungarian center, but also to identify a subgroup of items therein, possibly produced in the same workshop. The area of toreutics from the Ural-Hungarian center in the territory of Western Siberia is now expanded to include southern regions up to the mouth of the Irtysh.

All the previously found dishes from this center represent images of real people and animals. The medallion of the Kazym Khanty dish is the first product of this center that depicts a mythical creature—griffin. Moreover, its resemblance to the figure of a griffin on the cast silver plaque is obvious. Let me remind you that N.V. Fedorova considered one of the main features of the Ural-Hungarian artifacts to be their similarity with bronze artistic castings of West Siberian production (for example, a dish showing an eagle owl standing on a deer) (2019: 76); her opinion can be extended to the cast silver items. These plaques probably also belonged to the products of the Ural-Hungarian center; therefore, they can be dated to the 9th–10th centuries.

Another feature of the products described in this article is the first recorded graffiti, which was applied over the already existing composition. It is important that the anthropomorphic face was scratched on the chest of a bird of prey (see Fig. 1, c ). The author of the drawing possibly used the bronze cast image of a bird with open wings and a mask on its chest as a model. Such castings often occur at medieval sites in the north of Western Siberia (see, e.g., (Baulo, 2011: Cat. 290, 292, 294, 300, 301; and others)).

There are two answers to the question of why the silver dishes and the copper plaque survived in the ritual practice of Ob Ugrians. First, the images of a deer or a bird snatching a fish were understandable to the Siberian population. Second, there is a connection with the mythological ideas manifested in the images on the silver medallion from the Kazym River: they could have

The main technological and ornamental features of the Ural-Hungarian center products of the separate subgroup

|

Features |

Eagle owl on a deer * (bowl) |

Horseman and lion * (bowl) |

Bird and fish (bowl) |

Deer (plaque) |

Deer (bowl) |

Griffin (medallion) |

“Feast” (bowl) |

|

Bowl made of three silver sheets |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– (copper) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Pattern of two parallel |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

arches and a vertical |

(On the |

(On the |

(On the |

(On the |

(On the |

(On the |

(On the |

|

dash with three round imprints of a punch, arranged in a pyramid |

border) |

horseman’s belt, on the horse’s harness) |

border) |

border) |

border: only arches) |

border) |

belt) |

|

Completion of lines with a pattern of three imprints of a punch, arranged in a pyramid |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

|

Punch imprint on the paw |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

|

Punch imprint at the base of the beak |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

|

Vertical outgrowth on the belly line |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

|

Ornamentation of feathers of tail and wings with notches |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

|

Long cloven hooves |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

– |

– |

|

Large almond-shaped eyes with iris but no pupil |

– |

+ (Horseman, horse, lion) |

– |

– |

– |

– |

+ (Man, woman) |

*Published (Baulo, Marshak, Fedorova, 2004).

been correlated with a deity popular among the Voguls and Ostyaks— Mir-susne-khum , who in the legends rode a winged horse*, which in time of danger was able to turn into a goose (Gondatti, 1888: 18).

Unfortunately, information about the use of these items is minimal, which is largely due to the concealment of the religious sphere of the Ob Ugrians**; in any case, they are classified as “antiques”. The dish with the figure of a deer, judging by the presence of a hole in it, was hung up during ritual actions; other dishes were probably used to place sacrificial food on them during ritual actions with a request for successful deer hunt, safety of deer herds, rich fish catch, etc.

The publication of new samples of toreutics of the Ural-Hungarian center allows us to specify its main features and bring more clarity to the complex picture of the formation of art schools in young states and pre-state formations in the north-east of Europe, such as Volga Bulgaria, Great Hungary, and the Kama towns.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the designer M.O. Miller (IAET SB RAS) for preparing graphic images of items for publication, and A.A. Bogordaeva (FRC Tyumen Scientific Center SB RAS) for consultations on the description of clothing.

Список литературы Artifacts from the Ural-Hungarian center (800–1000 ad), recently found at Ob Ugrian sanctuaries

- Baulo A.V. 2002 Iranskiye i sredneaziatskiye sosudy v obryadakh obskikh ugrov. In Problemy mezhetnicheskogo vzaimodeistviya narodov Sibiri. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 12–27.

- Baulo A.V. 2011 Drevnyaya bronza iz etnograficheskikh kompleksov i sluchaynikh sborov. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN.

- Baulo A.V. 2013 Without a face: A silver plaque from the eastern slopes of the Urals. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, No. 4: 123–128.

- Baulo A.V., Marshak B.I., Fedorova N.V. 2004 Silver plates from the Voikar river basin. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, No. 2: 107–114.

- Belenitsky A.M. 1973 Monumentalnoye iskusstvo Pendzhikenta. Zhivopis, skulptura. Moscow: Iskusstvo.

- Chernetsov V.N. 1957 Nizhneye Priobye v I tys. n.e. In Kultura drevnikh plemen Priuralya i Zapadnoy Sibiri. Moscow: pp. 136–246. (MIA; No. 58).

- Darkevich V.P. 1976 Khudozhestvenniy metall Vostoka. Proizvedeniya vostochnoy torevtiki na territorii yevropeiskoy chasti SSSR i Zauralya. Moscow, Leningrad: Nauka.

- Drevniye bronzy Obi. 2000 Kollektsiya bronz IX–XII vv. iz sobraniya Surgutskogo khudozhestvennogo muzeya. Surgut: Izd. Surgut. khudozh. muzeya.

- Dyakonov M.M. 1954 Rospisi Pyandzhikenta i zhivopis Sredney Azii. In Zhivopis Drevnego Pyandzhikenta. Moscow: Izd. AN SSSR, pp. 83–158.

- Fedorova N.V. 2003 Torevtika Volzhskoy Bolgarii. Serebryaniye izdeliya Х–ХIV vv. iz zauralskikh kollektsiy. In Trudy Kamskoy arkheologoetnografi cheskoy ekspeditsii, iss. III. Perm: Izd. Perm. Gos. Ped. Univ., pp. 138–153.

- Fedorova N.V. 2019 Sever Zapadnoy Sibiri v zheleznom veke: Traditsii i mobilnost: Ocherki. Omsk: [Tip. “Zolotoy tirazh”]. Finno-ugry i balty v epokhu Srednevekovya. 1987 Moscow: Nauka.

- Gondatti N.L. 1888 Sledy yazycheskikh verovaniy u inorodtsev Severo- Zapadnoy Sibiri. Moscow: [Tip. Potapova].

- Marshak B.I. 1971 Sogdiyskoye serebro. Moscow: Nauka.

- Marshak B.I. 1996 Vstupitelnaya statya. In Sokrovishcha Priobya. St. Petersburg: Gos. Ermitazh, Formika, pp. 6–44.

- Marshak B.I. 2017 Istoriya vostochnoy torevtiki III–XIII vv. i problem kulturnoy preyemstvennosti. St. Petersburg: Akademiya issledovaniya kultury.

- Sokrovishcha Priobya. 1996 St. Petersburg: Gos. Ermitazh. Sokrovishcha Priobya: Zapadnaya Sibir na torgovykh putyakh srednevekovya: Katalog vystavki. 2003 Salekhard, St. Petersburg: [s.n.].

- Spitsyn A.A. 1906 Shamanskiye izobrazheniya. In Zapiski otdeleniya russkoy i slavyanskoy arkheologii Russkogo arkheologicheskogo obshchestva, vol. 8 (1): 29–145.

- Srednyaya Aziya v rannem Srednevekovye. 1999 Moscow: Nauka.

- The Gold of the Avars. 2002 The Nagyszentmiklós treasure. Budapest: Durer Printing House.

- Trever K.V., Lukonin V.G. 1987 Sasanidskoye serebro. Sobraniye Gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha. Khudozhestvennaya kultura Irana III–VIII vv. Moscow: Iskusstvo.