Artistic metalwork found near the Tomskaya pisanitsa

Автор: Kononchuk K.V., Marochkin A.G.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145386

IDR: 145145386 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2018.46.3.083-091

Текст обзорной статьи Artistic metalwork found near the Tomskaya pisanitsa

In July 2015, during the clearing of one of the crevices above the rock planes of the Tom rock art site (“Tomskaya Pisanitsa”), a participant of the petroglyphic expedition A.S. Tekhterekov discovered a cast figure of a horse or onager. Three more objects of artistic metalwork (two anthropomorphic masks and an ornithomorphic pendant) have been discovered in various years in the vicinity of the site. Out of these finds, only the representation of the bird has been partially published (Kovtun, 2001: 45), while the rest of the objects for various reasons have remained

unknown to the scholarly community. The analysis of these objects allows us to re-address the issue of cultic practices at the largest petroglyphic site of the Lower Tom region.

Description of the objects of artistic metalwork

Plaque in the form of an onager/horse figurine . The plaque was found in the lower part of the crevice-watercourse, which stretched from the northwest to southeast, above the plane with the rock representations of the second group

Fig. 1. Tomskaya Pisanitsa.

1 – plane with rock art representations; 2 – place where the figurine of the horse/onager was found.

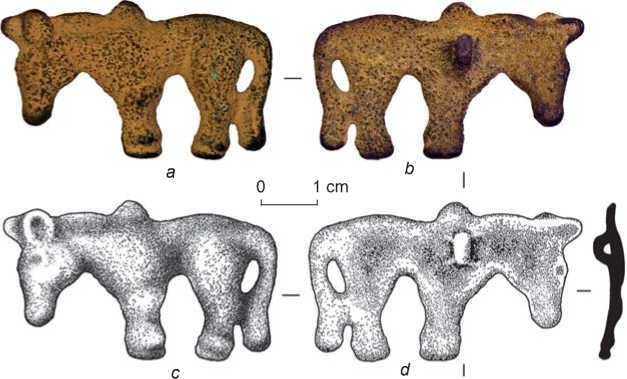

Fig. 2 . Pendant in the form of a horse/onager figurine. a , b – photo; c , d – drawing; a , c – front side, b , d – back side.

lowered down (Fig. 2). A loop for a horizontal belt is on the reverse side. The size of the object is 46 × 27 × 10 mm; the weight is 16.88 g. The entire surface is covered with patina. The elemental composition was determined by the X-ray fluorescence method, using the ArtTAX (Brüker) spectrometer, at the Department of Scientific and Technical Expertise of the State Hermitage (expert S.V. Khavrin): copper – over 97 %, arsenic – 0.5–1.0 %, lead – 0.2–0.6 %, nickel – 0.1–0.5 %, iron – 0.1–0.5 %, and trace amounts of tin. The object was essentially made of pure copper.

The forms are rendered in a realistic manner. Bangs are shown above the forehead. Oval-triangular ears are set vertically; the right ear slightly protrudes forward. The eye is rendered with an oval. The nostrils and mouth are not very prominent due to patina. The head is delimited from the neck by a higher relief of the cheekbones. The withers are rendered in the form of a pronounced hump. The scapula is shown in higher relief than the trunk and thigh which is separated from the abdomen by an indentation. The legs are robust and short. A long tail is bent down and is adjacent to the shanks of the hind legs.

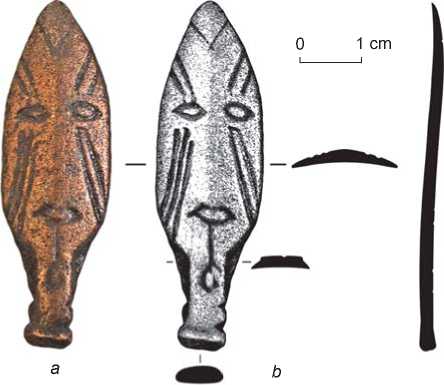

Anthropomorphic mask with a pointed upper part . It was found in the 1970s at the site above the rock with the representations of the second group (according to the oral report of V.V. Bobrov). The finder is unknown, just as the real context of the discovery. The mask was made in the technique of flat planar casting. The size of the object is 55 × 18 × 2 mm; the weight is 9.58 g. The shape of the object is close to ellipsoidal, with a sharp ending of the upper part and elongated rectangular base, the edges of which were not processed after casting. The image was applied to the outer “convex” side (Fig. 3).

The facial features and elements of headdress are shown with slightly

(Fig. 1). The object lay in a mass of loose deposits of gravel and earth, and most likely was moved relative to its original location. The plaque is a relief figure of a horse or onager, turned to the left, with the neck extended forward and head

deepened contours. The transverse divider between the face and the headdress is missing as well as any relief designations of the nose and chin. The pointed top of the object has a diamond-like outline by means of a

Fig. 3 . Anthropomorphic mask with pointed top. a – photo; b – drawing.

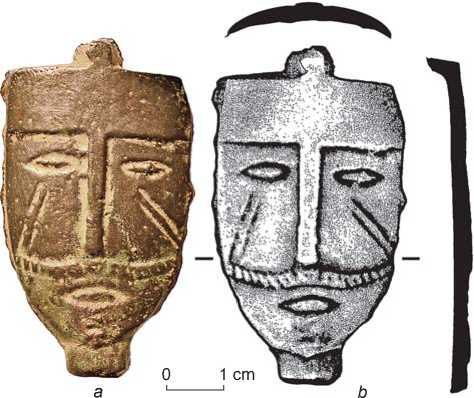

Fig. 4 . Anthropomorphic mask with truncated top. a – photo; b – drawing.

V-shaped mark. The eyes and mouth are depicted in the form of isomorphic horizontal ellipses with unfilled inner space. Paired short lines directed from the edges of the mask to its center are above the eyes. Three slightly curved lines run diagonally down from the right eye, and two almost straight lines run diagonally from the left eye. A vertical line with a looped end is drawn from the mouth to the middle of the neck. Two small notches were symmetrically made on the side faces in the lower part of the bottom, probably for attaching the object to some base. The bottom is marked with a small bas-relief band.

Anthropomorphic mask with truncated upper part . It was discovered in the 1990s on the right bank of the Pisanaya River, not far from its mouth, that is, in the immediate vicinity of the first group of drawings (oral report of G.S. Martynova). The object has been relatively well preserved; most of its surface is covered with noble patina. The mask was made in the technique of flat casting. Unpolished casting burrs can be seen around the outline. The size of the object is 59 × 33 × × 2 mm; the weight is 27.3 g. The shape of the object is semioval, with a truncated upper part. A neck-base of subrectangular shape is at the bottom. A small subrectangular protrusion is located symmetrical to the base, on the upper cut of the mask. The representation was made on the outer “convex” side (Fig. 4).

The eyes and mouth are shown as isomorphic horizontal ellipses with unfilled inner space. Pairs of diagonal lines run downward from the eyes. The line of the headdress or eyebrows, nose or helmet nose-guard, and a mustache are rendered in bas-relief.

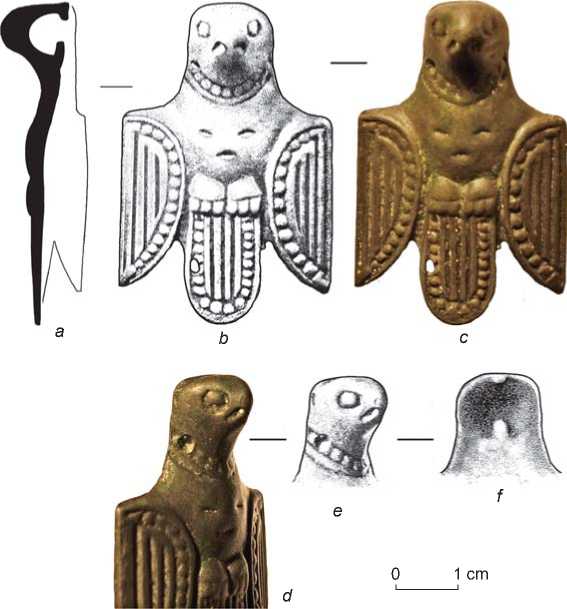

Ornithomorphic pendant . It was found in 1991 at the foot of the rock near the drawings of the second group by

Fig. 5 . Ornithomorphic pendant.

a , b , e , f – drawing; c , d – photo; a – longitudinal cross-section at the center; b , c – face view; d , e – profile view of the upper part; f – back side of the upper part.

an employee of the Museum-Reserve (according to the oral report of G.S. Martynova). The pendant represents a realistic image of a bird of prey (falcon or eagle) in a so-called heraldic posture. The size of the object is 50 × 33 × × 22 mm; the weight is 18.67 g. The object was made in the technique of flat planar casting. It is well preserved; the entire surface is covered with noble patina (Fig. 5). The front side of the pendant is convex; the back side is slightly concave, without representations; the remains of a loop for passing a strap through have survived in the upper part of the back side. A patinated conical depression is on the right in the area of the bird’s neck; the origin and purpose of this depression remain unclear.

The head is prominently emphasized; depressions on the head mark round eyes and a curved beak. A long neck is decorated with a semicircular “necklace”. The wings are bent down; together with an elongated semioval tail they are marked with bands and a small pearl-like pattern; their inner space is filled with vertical bands. Paws with clasped claws are prominently emphasized above the tail. On the chest of the bird, a stylized mask is shown with three lenticular depressions.

Cultural and chronological attribution of the objects, based on their stylistic parallels

The cultural and chronological attribution of archaeological objects found out of context is most often based on the method of analogy, and is often hypothetical. However, the circle of stylistically close objects for the objects under consideration can be determined quite clearly. Apparently, the earliest of our objects is a zoomorphic plaque-pendant in the form of a horse/onager figurine. According to the specialists, this image emerged in southern Siberia during the Scythian period, and is associated with the culture of steppe tribes (Molodin, Bobrov, Ravnushkin, 1980: 46). The image of a standing horse or onager in the south Siberian artistic metalwork of that time was used to decorate the handles of cauldrons, high reliefs, and pommels on the handles of knives of the Tagar culture (Amzarakov, 2012; Zavitukhina, 1983: 64). A series of three-dimensional figurines of an onager with bent legs, “lying” on bronze mirrors, is known from the Achinsk-Mariinsk forest-steppe and to the north of it, from the materials of Aidashin Cave (Molodin, Bobrov, Ravnushkin, 1980: Pl. XI, 5 ; XII) and the Ishim hoard (Plotnikov, 1987: Fig. 1, 1–11 ). A similar object was found in the Minusinsk Basin (Zavitukhina, 1983: 64, fig. 156). It has been suggested dating such figurines to the transitional Tagar-Tashtyk period (Molodin, Bobrov, Ravnushkin, 1980: 45–46).

Cast figurines of horses from the Stepanovka and the Shelomok hoard in the Tomsk region of the Ob are the most similar (almost identical) to the zoomorphic plaque-pendant (Pletneva, 1976: Fig. 27, 15; 2012: 18–20). In addition to their three-dimensional nature, the common feature of all the objects is the presence of fastening devices—loops (on the finds from the Shelomok hoard and from the vicinity of the Tomskaya Pisanitsa) and a small rod with a head (on the figure from Stepanovka). When analyzing the Stepanovka find, Pletneva showed its typological similarity to the figurines of the 5th–4th centuries BC from the Tagar cemetery of Malaya Inya (the southern part of the Krasnoyarsk Territory) (Chlenova, 1967: Pl. 25, 21) and the sanctuary on Lysaya Gora on the Yaya River (northern foothills of the Kuznetsk Alatau) (Ibid.: Pl. 34, 6; Martynov, 1976: Fig. 1, 63). These parallels are also valid for the figurine from the vicinity of the Tomskaya Pisanitsa. Taking the above into consideration, the time when this zoomorphic image was created falls within the 5th–4th centuries BC. A later placement of the object on the rock is possible. Culturally, the object is close to the Tagar antiquities from the Achinsk-Mariinsk foreststeppe or the Kizhirovo (Shelomok) assemblages of the Tomsk region of the Ob, genetically associated with the Tagar world.

Both anthropomorphic masks are examples of anthropomorphic casting which emerged at the late stage of the Kulaika historical community, in the southeastern part of its habitation area (according to Y.P. Chemyakin, the Tomsk-Narym version of the Kulaika artistic metalwork) (Chemyakin, 2013). According to the typology of Z.N. Trufanova, oval masks with a pointed top constitute the second iconographic type of anthropomorphic images of the Kulaika planar casting, while truncated-oval masks constitute the fourth type (2003: 16). Such a typical Late Kulaika trait as “negligence” of execution expressed in unpolished edges and other minor defects (Polosmak, Shumakova, 1991: 7–8) can be observed in both objects.

The “sharp-headed” representation from the vicinity of the Tomskaya Pisanitsa in the context of the second iconographic type has a strong resemblance to the “helmet-headed” Parabel mask from the Middle Ob region, dated to the last third of the first millennium BC (Chindina, 1984: 75, 106) or to the turn of the eras (Borodovsky, 2015: 94). Two Late Kulaika masks from the collection of random finds of the Novosibirsk Museum of Local History (Polosmak, Shumakova, 1991: Fig. 8, 5, 6) are even more similar to this object. Iconographically, they have in common: “sharp headedness”, roundness of forms, presence of a pronounced neck-base, dashed decoration of the assumed headdress area, and ellipsoidal outlines of the eyes and mouth. Curved lines-“tattoos” under the eyes are noteworthy. Specific features of the mask from the vicinity of the Tomskaya Pisanitsa include its miniature scale, emphasized stylized nature, absence of dividing lines between the face and headdress area, as well as absence of images of nose and chin.

Our objects show very great similarity to the pointed mask from the mound of barrow 60 of the Timiryazevo I burial ground, dated by O.B. Belikova and L.M. Pletneva to the 5th–6th centuries AD and attributed to the beginning of the Early Middle Ages (1983: Fig. 12, 7 ). The authors correlate this period in the Tom region of the Ob to the end of the merging of the local population with the Kulaika population (Ibid.: 127), which theoretically confirms the connection of the masks of this type with the Late Kulaika pictorial tradition. Finally, we should note the differences between the finds from near the Tomskaya Pisanitsa and the rhomboid anthropomorphic masks forming the early medieval trans-cultural material complex of Western Siberia (Borodovsky, 2015): roundness of outlines, and absence of bas-relief elements and fastening protrusions on the ends (Ibid.: Fig. 1, 3 , 4 ).

The face with the truncated upper part finds numerous parallels in the materials from cultic places and hoards of the Tomsk-Narym region of the Ob and the Middle Tom region. Noteworthy are also the objects from the Kulaika and Parabel cultic places (Chindina, 1984: Fig. 17, 3 , 4 ; 35, 3 ), as well as the Ishimka (Plotnikov, 1987: Fig. 1, 1 ) and Elykaevo (Mogilnikov, 1968: Fig. 3, 9 ) hoards. L.A. Chindina established the emergence and existence of such objects during the Sarov stage (1984: 122), but she also allowed for the medieval dating of some of them, for example, of the masks from the Lisiy Mys and the Elykaevo hoard (Chindina, 1991: Fig. 20, 8 , 9 ). In the latter case, this does not contradict the medieval attribution of the Elykaevo collection, which was previously proposed by V.А. Mogilnikov (1968: 268).

However, there are two points of view concerning the dating of the so-called “mixed” hoards of Western Siberia, which include masks similar to those under consideration. The first point of view is proposed in the studies of V.А. Mogilnikov (1968) and Y.A. Plotnikov (1987: 125), who date such accumulations of objects to the medieval period, because of the presence of iron weaponry. Another point of view belongs to Y.V. Shirin, who suggested limiting the upper date of the “mixed” hoards to the 5th century AD, and to correlate them with the Late Kulaika tradition of the votive “burials” of objects in cultic places, based on the morphology of iron weaponry of the Fominskoye culture and the absence of medieval belt sets (1993: 159–161; 2003: 120). Such a suggestion seems to be more convincing, and if it is true, the “medieval” age of some anthropomorphic masks should be reconsidered for the earlier dating. However, the literature has repeatedly noted the genetically conditioned closeness of the Late Kulaika and early medieval (Relka) metal artwork, the differentiation of which is often possible only in context (Chindina, 1991: 61–63, 66–68). Taking this into account, it would be logical to date the masks under consideration to a wide chronological range from the turn of the eras up to the sixth century, with a Late-or post-Kulaika affiliation.

The stylistic canon, according to which the ornithomorphic pendant was made, also emerged in the Late Kulaika period (Chindina, 1984: 72–74; Trufanova, 2003: 19). In the Early Middle Ages, this image received wide trans-cultural proliferation in the Urals and in Western Siberia, including the Relka and Upper Ob cultures of the Upper and Middle Ob region (Chindina, 1991: 58–59, fig. 22, 2 ; Troitskaya, Novikov, 1998: Fig. 19). Regarding the Middle Tom region and the Kuznetsk Depression, the latest dating of such images does not go beyond the limits of the 6th–7th centuries AD (Kuznetsov, 2013). Apparently, the pendant from the vicinity of the Tomskaya Pisanitsa should be dated to that same period.

Finds in the context of cultic places of the Early Iron Age and the Early Middle Ages in Western Siberia

The discovered objects belong to chronologically different periods. The earliest image has a Tagar or Kizhirovo appearance and is dated to the mid–second half of the first millennium BC, while the rest of the objects are associated with the Late or post-Kulaika cultic casting and belong to the first half of the first millennium AD, possibly the 6th–7th centuries AD. Once again, the objects do not form a single local cluster, as is the case at the Parabel or Ishimka cultic sites. Their “burial” is associated with locations separated by tens of meters. Most likely, we are dealing with the remains of several hoards of different periods or with placement of individual objects. Unfortunately, the full archaeological context of these remarkable finds remains unknown. At the same time, the concentration of “exclusive” objects over a relatively small area requires an explanation. It would be quite logical to suggest that the finds belong to a cultic place, by analogy with the well-known cultic sites of the Early Iron Age and the Early Middle Ages (Kulaiskaya Gora, Parabel, Ishimka, and others).

It is common knowledge that cultic places in the Urals–Western Siberian region are confined to remarkable and unusual elements of the terrain. In the forest zone of the Urals, such places are caves, rocks, mountains, hills, islands on lakes, or marshes (Kultoviye pamyatniki…, 2004: 315–316). In Western and southern Siberia, they are most frequently hills, which dominate the terrain (the Kulaiskaya Gora and the Parabel cultic place in the Middle Ob region, the ritual complex at the mouth of the Kirgizka River, and the cultic sites at the settlement of Shelomok in the Tomsk region of the Ob (Pletneva, 2012: 168), Lysaya Gora in the Tom-Yaya interfluve), and rarer variants—islands and caves (the Ishimka hoard in the Tom-Chulym interfluve (Plotnikov, 1987), and Aidashinskaya Cave in the Achinsk-Mariinsk forest-steppe (Molodin, Bobrov, Ravnushkin, 1980; Molodin, 2006: 43–59)). The Tomskaya Pisanitsa fully corresponds to these requirements—a picturesque cliff hanging over the Tom and Pisanaya Rivers forms the base of a high hill. Together, the geomorphological features and the finds of artistic metalwork make it similar to other cultic places of the Early Iron Age and the beginning of the Early Middle Ages in Western Siberia. It is most likely that the horse/onager figurine is associated with the cultic practices of the pre-Kulaika, Scythian population of the Tom region, while the remaining objects are associated with the late Kulaika or post-Kulaika period of the sanctuary’s functioning.

Finds as a manifestation of the tradition of setting up altars at petroglyphic sites

The term “sacrificial place”/“altar” for the archaeological materials discovered near rock art sites was first used by O.N. Bader in the 1950s (see: (Mazin, 1994: 67)). A little later, a similar idea was formulated by A.P. Okladnikov in his analysis of the rock art sites of Suruktakh Khaya in Yakutia and Narin-Khunduy in Trans-Baikal region (Okladnikov, Zaporozhskaya, 1969: 6, 40; 1972: 9–10). Okladnikov established the criteria for such cultic sites: duration of functioning, presence of sacred objects (devices for obtaining fire, arrowheads, etc.), and traces of ritual sacrifices, which have parallels in ethnography (Okladnikov, Zaporozhskaya, 1970: 114; 1972: 35–41, 78–81).

A.V. Tivanenko considered the rock art sites as an element of cultic places associated with worshiping the spirits of the land. He saw the localization of archaeological materials from various chronological periods near the planes (under them, over them, in crevices, etc.) as being signs of a sanctuary (Tivanenko, 1989: 5, 6; 1990: 92–94, 97). A.I. Mazin identified two types of altars at the rock art sites of the Amur River region: ground altars (typical of the forest zone) and altars inside special stone enclosures (common in the steppe and forest-steppe Eastern Trans-Baikal). He established four main types of cultic practices: making drawings and purification by fire, after which the rock became untouchable; making additional drawings; offering of improvised things in the case of accidentally approaching the petroglyphs; and offering things during a special visit (Mazin, 1994: 67–71). The proposed model, in our view, is largely universal. The available data indicate wide proliferation of such practices on the territory of Northern Asia in ancient times, the Middle Ages, and ethnographic modernity.

The Urals. The study of the archaeological context of the Ural rock art sites has been carried out since the 1940s (Bader, 1954: 254). The most studied complex is the Vishera painted rock where over 6000 various artifacts have been discovered on an area of 140 m2 (Kultoviye pamyatniki…, 2004: 315–316). Cultic places are known at the Alapaevsk, Irbit, Tagil, and Turinsk painted rocks, as well as the Balakino, Pershino, Shaitan, and Shitovskoye rock art sites, Balaban I rock, etc. (Shirokov, Chairkin, 2011: 17, 30, 35, 38, 41, 87, 102, 116; Dubrovsky, Grachev, 2010: 115, 124, 138).

Eastern Siberia . In the Amur Region, Mazin has discovered ancient altars at 37 out of 52 examined rock art sites (1994: 36). In the Cis-Baikal region, A.V. Tivanenko has conducted successful excavations at the foot of 40 petroglyphic sites (1994: 20). N.N. Kochmar has reported about 56 altars associated with 19 rock art sites of Yakutia (1994: 146). In the Angara basin, already in the 1930s, Okladnikov identified a cultic place at a rock art site on the Kamenka River, the cultural layer of which included fragments of pottery, bone and bronze arrowheads, and a bronze Tagar mirror (1966: 103). The Ust-Taseyevo cultic complex, explored in the 1990s by Y.A. Grevtsov, is unique not only for the Angara region, but also for all of Siberia. Its materials go back from the Early Iron Age to the ethnographic period with the predominance of objects made in the Scytho-Siberian animal style (Drozdov, Grevtsov, Zaika, 2011).

Southern Siberia . Only one such location is known on the Yenisei River, despite numerous petroglyphic complexes in the region. This is the burial of the mid first millennium BC, found in 2004 during the clearing of debris from the Shalabolino rock art site (Zaika, Drozdov, 2005: 113). In the Altai Mountains, archaeological materials are known from the excavations near petroglyphs at Kyzyk-Telan, Ayrydash, near the village of Kokorya, and at Kalbak-Tash (Surazakov, 1988: 74; Kubarev, Matochkin, 1992: 24, 25). The cultic complex in the grotto of Kuylyu, on the Kucherla River, is unique; its cultural deposits partially covered the drawings located on vertical planes. The materials of the Afanasievo period, Scythian period, the Middle Ages, and the ethnographic period have been discovered at this site (Molodin, Efremova, 2010: 199).

Until recently, such information was fragmentary for the rock art sites of the Lower Tom River. Accumulations of bones, charcoal, and pottery on the slopes of the Tomskaya Pisanitsa (Martynov, 1970: 27–28), or a bronze arrowhead accidentally found in a crevice at the same site (Kovtun, 2001: 46) were considered cultic altars. In 2008–2012, the Dolgaya-1 site was excavated at the Novoromanovo rock art site; a part of the materials from Dolgaya-1 can be reliably linked to the cultic practices of the Bronze Age and the transitional period to the Iron Age (Kovtun, Marochkin, 2014). Objects of cultic artistic metalwork have not yet been found at this site in spite of abundant pottery of the Early Iron Age and the Early Middle Ages (the latter circumstance can be explained by a variety of reasons, including the fact that, unlike the Tomskaya Pisanitsa, the Novoromanovo rock art site is located on a low, annually flooded base).

It seems quite logical that the objects of artistic casting discovered at the Tomskaya Pisanitsa are the manifestation of the trans-epochal and trans-cultural tradition of sacrifice at rock representations, typical of Northern Asia. Apparently, we should speak about a combination of traditional forms of sacralization based on the practice of burying things in cultic places. It is possible to distinguish between these traditions only conditionally. It cannot be ruled out that the petroglyphs, which were originally made as one of the ritual practices within the cult of “special” places, turned into an independent factor of sacralization of such places.

Conclusions

The earliest images of the rock art sites of the Lower Tom River are proposed to be dated to the Neolithic (Okladnikov, Martynov, 1972) or the Samus period of the Bronze Age (Kovtun, 1993; 2001; Molodin, 2016: 42, 50). A layer of drawings of the Late Bronze Age has been identified (Kovtun, 2001: 52, 66; Kovtun, Rusakova, 2005). This means that some Lower Tom rock art sites had existed for several millennia by the beginning of the Iron Age.

Materials of the Scythian period from the Kuznetsk Depression characterize it as a “neutral” zone, which was being actively inhabited by the Bolshaya Rechka population and was simultaneously influenced by the Yenisei population (Bobrov, 2013: 285). As a scenario of their interaction, Bobrov allowed for the movement of small groups. In the context of this scenario, we consider it quite likely that not only the Tagar but also the Kizhirovo (Shelomok) population penetrated into the Middle Tom region, especially since there was a common river route. The archaeological confirmation is our image of the horse/onager (hypothetically, a sacrifice to the cultic place at the Tomskaya Pisanitsa).

At the end of the first millennium BC, the late Kulaika population came to the Middle Tom region, as is evidenced by the presence of the corresponding cultic and burial complexes, and settlement pottery (Pankratova, Marochkin, Yurakova, 2014). According to Shirin, the Kulaika component actively participated in the processes of cultural genesis on the southern periphery of the late

Kulaika community, including the Tom region, which ultimately led to formation of the Fominskoye culture of the 2nd–4th centuries AD (2003: 158–159).

One of the possible variants of sacralization of the Lower Tom rock art sites by the Kulaika population was creating their own rock representations – and the presence of such representations has been repeatedly suggested by specialists (Chernetsov, 1971: 105; Bobrov, 1978; Lomteva, 1993; Trufanova, 2003; Rusakova, 2015), although it still remains a subject of discussion (see review in (Kovtun, Marochkin, 2014)). The use of the objects of planar casting for organizing plot-based compositions, that is, a kind of imitation or replacement of static rock planes, might have been another way of sacralization. This interesting suggestion belongs to Bobrov (2008). Finally, the third variant, which does not exclude the first two, was the introduction of some ancient rock art sites into the system of cultic places with the typical tradition of votive “burials” of objects. Participation of the Kulaika cultural substratum in the formation of early medieval cultures of the Upper and Middle Ob regions suggests that this tradition could have been preserved in the second half of the first millennium AD.

Acknowledgments

This study was performed under Public Contract No. 33.2597.2017/ПЧ. The authors are grateful to V.I. Molodin, V.V. Bobrov, A.I. Martynov, G.S. Martynova, I.V. Kovtun, L.V. Pankratova, and P.V. German for their valuable consultations, to L.Y. Bobrova and G.S. Martynova for the opportunity to publish the description of previously unknown objects, and to E.A. Miklashevich and S.V. Khavrin for organizing and conducting the elemental analysis of the find in 2015.