Belt sets of the "Redikar type" in medieval cemeteries of the Volga Finns

Автор: Zelentsova O.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145431

IDR: 145145431 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.2.060-068

Текст обзорной статьи Belt sets of the "Redikar type" in medieval cemeteries of the Volga Finns

The burial grounds of the Volga Finns in the basin of the Lower Oka River of the late 1st to the early 2nd millennium AD are distinguished by a large number of military graves containing richly decorated composite belts. This part of the male outfit was traditionally considered to be a marker that the buried person belonged to the military class. The composition of the belt set, number of plaques, presence of hanging straps, etc., indicated the rank and status of the warrior in the community or in the military hierarchy. As a rule, specialists consider the belts to be a supra-ethnic category of adornments, but admit that they appeared among the sedentary population under the influence of nomadic tribes (Kovalevskaya, 1979).

This article discusses belt sets of one of the types that scholars associate with the antiquities of the Magyars from the period when they acquired their homeland, namely, belts with metal plaques similar to those found in the 2nd Redikar hoard (Shablavina, 2016: 361–362). This treasure, discovered in the early 20th century, included two belt sets. The belt set of interest to us consists of belt plaques of sub-triangular and arched shape made of gilded silver and decorated with a distinctive nodular border and ornamental décor in the form of lotus-like buds (Ibid.: Ill. 274, 275). The place of the hoard’s discovery is very remarkable. It is the vicinity of the village of Redikar in Chardynsky Uyezd of the Perm Governorate, where the medieval settlement and cemetery were located, and where several treasures

Another belt with similar sub-triangular and arched plaques, as well as rounded plaques with a loop and relief ring, was found in the early 20th century near the village of Novo-Nikolaevka in Yekaterinoslavsky Uyezd of the Yekaterinoslav Governorate (now the village of Novonikolaevka in the Dnepropetrovsk Region, Ukraine) (Khanenko B., Khanenko V., 1902: Pl. XIX, 645, 668, 679, etc.). According to E.A. Shablavina, the Redikar and Novonikolaevka plaques were made according to the same template (2016: 362). This conclusion certainly needs to be checked, but it is impossible to ignore the striking similarity and uniformity of these plaques.

One of the first scholars who studied the belt set of the 2nd Redikar hoard, was N. Fettich, who included this complex in the circle of Magyar antiquities (1937: Fig. XIV). A.V. Komar attributed the Redikar and Novonikolaevka belts to antiquities of the Subbottsy type, which according to him included Babichi, Tverdokhleby, Korobchino, Katerinovka, Bolshiye Tigany, and other sites associated with the distribution area of antiquities belonging to the time of the Magyar migration to the Carpathian Basin (2011: 56, 58–59, 68–69). Some scholars believe that such belts mark Magna Hungaria— the area inhabited by the ancient Hungarian tribes prior to their movement to the west. They assign to these territories the western Urals (Perm), southern Urals (Bashkiria), part of the eastern Urals, and the left bank of the Kama, where a part of the Ugric or related tribes remained after departure of the main group of the Magyars (Belavin, Krylasova, Podosenova, 2017: 4).

In connection with this, it is interesting to ask the question of what kind of phenomena or processes can belt sets of the Redikar type in the cemeteries of the Volga Finns testify to: presence of the proto-Hungarian population in the western part of the Middle Volga basin, or phenomena of a social, political, or cultural nature, which occurred at the turn of the 1st and 2nd millennia AD in the territories west of Magna Hungaria.

Description of archaeological evidence

Three assemblages with belts decorated with Redikar type plaques have been found in Finnish cemeteries of the Lower Oka basin. Two belts were discovered in the early 20th century on the Middle Tsna River (the right tributary of the Moksha River) at the Elizavet-Mikhailovsky and Kryukovsko-Kuzhnovsky cemeteries of the Mordvins. The third find was a bridle set decorated with plaques of the Redikar type, which was found in 2012 in the Lower Oka region, at the Podbolotyevo cemetery of the Muromians. Analysis of the burials containing these artifacts makes it possible to clarify the date of the Redikar belt sets, and establish the mechanisms and paths of their distribution on the territories inhabited by the Mordvins and Muromians.

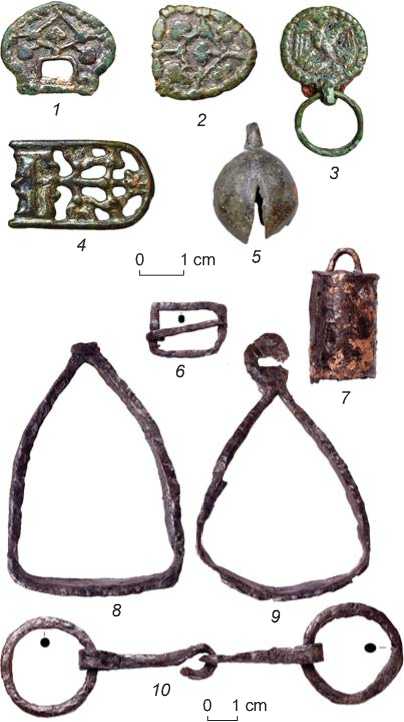

The most complete set of belt plaques of the Redikar type has been found in the burial of the “jeweler” (burial 115) at the Elizavet-Mikhailovsky cemetery (Materialnaya kultura…, 1969: 70, pl. 42, 13–17 ). It consisted of ten sub-triangular plaques, nine rounded belt plaques with a slit, and five round belt plaques with a ring (Fig. 1, 2–4 ). A hinged buckle with a U-shaped shield decorated with floral ornamentation (Fig. 1, 5 ) was at one end of the belt; a pentagonal tip with nodular border, lotuslike buds, and representations of an eagle owl and eagle (falcon?) in heraldic postures (Fig. 1, 1 ) was at the other end. An earring of the Saltov type, two syulgam clasps, two spiral finger-rings, and a wire bracelet were found in the burial (Fig. 1, 7–10 , 12 ). A set of jewelry tools, nonferrous metal scrap, bridle bit, and axe-celt were at the feet of the deceased (Fig. 1, 6 , 11 ) (Ibid.: Pl. 42, 1–9 ).

Another belt set, which included plaques of the Redikar type, was found in military burial 69 at the Kryukovsko-Kuzhnovsky cemetery (Materialy po istorii…, 1952: 31). The military nature of that burial was marked by a battle axe, axe-celt, ice pick, set of arrows, bridle bit (Fig. 2, 6 , 7 , 14 ), and two earrings of the Saltov type (Fig. 2, 8 ), which are considered to have marked the representatives of the military class (Stashenkov, 1998: 216–218). The set of jewelry also included three syulgam clasps, a “mustached” finger-ring with widened middle, and a laminar bracelet with ends bent outward (Fig. 2, 9–13 ). The belt is represented by a hinged buckle with an oval frame and pentagonal shield with the Redikar ornamental décor (Fig. 2, 5 ), 17 oval plaques of the Redikar type, and 24 rounded plaques with a hanging ring (Fig. 2, 3 , 4 ). The latter plaques, just like the Redikar plaques, were decorated with a border in the form of a chain of ovals; the central part of the plaques was decorated with two symmetrically located rosettes with pointed side leaves. This quite recognizable decoration element (palmette with “disheveled” petals (according to B. Marshak)) appeared on Sogdian vessels of the 7th–8th centuries (Marshak, 1971: 52). Later, in the period when the Magyars acquired their homeland, such ornamentation became a typical element of décor on Hungarian toreutics. In the repoussé technique, it appeared on the sheaths of sabers and daggers, and on metal plaques on belt bags (The Ancient Hungarians, 1996: Pl. 80, 6 ; pl. 96, 23 ; pl. 120, 121, 1 , 2 , etc.). The above ornamental décor also appeared on belt sets, for example, on a buckle shield from the cemetery of Bashalom, Hungary (Fodor, 2015: 94).

In the Oka basin, at Podbolotyevo, in horse burial 60, a bridle with plaques of the Redikar type has been found (Zelentsova, Yavorskaya, 2014: 168). The horse

Fig. 1. Finds from burial 115 of the Elizavet-Mikhailovsky cemetery.

1–5 – elements of a belt set; 6 – celt; 7 , 8 – syulgams ; 9 – earring of the Saltov type; 10 – bracelet; 11 – bridle bit;

12 – spiral finger-ring.

Fig. 2 . Finds from burial 69 of the Kryukovsko-Kuzhnovsky cemetery.

1–5 – elements of a belt set; 6 – axe; 7 – celt; 8 – earring of the Saltov type; 9 – 11 – syulgams ; 12 – bracelet;

13 – finger-ring with widened middle; 14 – bridle bit.

was buried in full harness: with bridle, bell, stirrups, and bit (Fig. 3). The bridle set included a U-shaped tip with openwork ornamentation, two arched and 11 sub-triangular plaques of the Redikar type, and nine round plaques with pendant rings (Fig. 3, 1–4 ). The latter plaques had a border of knobs and the representation of an eagle attacking an animal (fallow deer?) in the central part. The eagle is shown in a heraldic posture with outstretched wings; due to poor casting, the figure of its victim is almost illegible (Fig. 3, 3 ).

Parallels and discussion

Another belt set was found at the Kryukovsko-Kuzhnovsky cemetery. Judging by the belt from burial 69, this belt set existed simultaneously with the items of the Redikar type and was obviously connected with them by the same manufacturing tradition. This composite belt, decorated with plaques with the “disheveled” palmette ornamental motif and borders of chains (Fig. 4, 1–4 ), was located in military burial 55 (Materialy po istorii…, 1952: 27). Its complete counterpart is a belt from military burial 279 at the Boyanovo cemetery in the western Urals (Perm) (Belavin, Danich, Ivanov, 2015: 125; Podosenova, 2017b: Fig. 2, 3). Belts from the Middle Tsna River and western Urals are identical both in design of the plaques and composition: they were assembled from heart-shaped simple and rounded plaques with pendant rings (Fig. 4, 2 , 3 ). Initially, the belt from the Kryukovsko-Kuzhnovsky cemetery was covered with a thin layer of gold, the traces of which have been preserved in the recesses of the ornamental décor. Traces of gilding are also present on

Fig. 3 . Finds from burial 60 of the Podbolotyevo cemetery. 1–4 – elements of a bridle; 5 – jingle bell; 6 – buckle; 7 – bell; 8 , 9 – stirrups; 10 – bridle bit.

Fig. 4 . Finds from burial 55 of the Kryukovsko-Kuzhnovsky cemetery. 1–4 – elements of a belt set; 5 – earring of the Saltov type; 6 , 7 – syulgams ; 8 , 9 – bracelets.

the Boyanovo plaques (Podosenova, 2017b: 150; Belavin, Krylasova, Podosenova, 2017: 2).

The assumption that such belt sets existed simultaneously with the belts of the Redikar type and were assembled in the same place is confirmed by the presence on the belt from burial 69 at Kryukovsko-Kuzhnovsky cemetery of plaques decorated with the palmetto with “disheveled” petals and plaques of the Redikar type (see Fig. 2, 2–4 ), as well as identical tips on the belt from Boyanovo and the belt from burial 115 at Elizavet-Mikhailovsky (see Fig. 1, 1 ) (see (Podosenova, 2017b: Fig. 3, 28)). These tips were decorated in the Redikar style with a nodular border along the edge, lotus-like buds in the narrowed part, and representations of two birds in lozenges in the central part. Judging by the expressive ears, the upper bird was an eagle owl, and the lower bird was an eagle or falcon. Both birds were depicted in heraldic posture (Fig. 1, 1 ).

The bird represented in heraldic posture was one of the most common subjects in cultic plastic arts of the Perm and Trans-Ural Ugrians. Plaques in the form of a bird shown in frontal view with wings wide open or in profile with folded wings are considered to be an ethnic marker of the Ugrian culture (Belavin, Ivanov, Krylasova, 2009: 176, fig. 73, 74; 217; Iskusstvo Prikamiya…, 1988: 167, fig. 85–89). The image of the eagle owl on the so-called “Platter with Eagle Owl” from the Voykar River in the Ob region is the closest to the representations described above ((Baulo, Marshak, Fedorova, 2004: Fig. 2), see ibid. for other parallels). This image was widespread in the cultures of the population of Western Siberia until the ethnographic time (Baulo, 2013: 566). Cultic plaques in the form of the eagle owl figure with human mask on the chest have been found throughout the entire territory inhabited by the Ugrians (Iskusstvo Prikamiya…, 1988: Fig. 13, 21).

Several plaques in the form of birds of prey with outstretched wings have been discovered in the Volga region, in the Mari cemeteries of Anatkasinsky, Veselovsky, Cheremisskoye Kladbishche, and Dubovsky, where contacts with the Ural territories were more pronounced (Nikitina, Vorobieva, Fedulov, 2016: 125, fig. 3, 10 ; Nikitina, 2012: Fig. 39, 4 ; 113, 6 ; 263, 9 ).

The Kama animal style also has a typical subject of an animal being attacked by a bird of prey, which appears on plaques with a ring, adorning the bridle from burial 60 at Podbolotyevo (Fig. 3, 3). This subject was widespread in ornamentation of medieval non-ferrous metalware in Eastern Europe ((Totev, Pelevina, 2005: 85–87); see ibid. for the secondary literature). Components of belt sets with the eagle in heraldic posture attacking an animal also appear among the Saltov artifacts. The finds from the Verkhne-Saltov and Podgornovsky cemeteries are the best known among such evidence (Pletneva, 1962: 244, fig. 2, 9; 1967: 150, fig. 40, 10). In the Mordvin cemeteries, this subject appears on the Saltov belt sets (Materialnaya kultura…, 1969: Pl. 21, 6; Peterburgsky, Aksenov, 2008: 12, fig. 10, 43). However, the plaques from Podbolotyevo were made according to the canon of the “Hungarian” style, known in the western Urals (Belavin, Krylasova, Podosenova, 2017: 3). This subject could well have emerged in the Ural territories. Thus, the subject of the eagle attacking an animal is known from the Sassanian dishes found in the Kama region (Voshchinina, 1953: 185, fig. 1; Leshchenko, 1966: 318, fig. 1; Darkevich, 2010: 70, pl. 4, 3). In the western Urals (Perm) and eastern Urals, this subject was embodied in cultic casting (Chernetsov, 1957: Pl. XVIII, 11, 13), knife pommels (Sokrovishcha Priobiya, 1996: Fig. 15, 17), and handles of fire strikers (Krylasova, 2007: 166, fig. 74; Iskusstvo Prikamiya…, 1988: 67, fig. 22).

All of the above shows that this style could have emerged and developed in the Ugric environment or more broadly in the western Urals. In the region where there was a long tradition of representing animals and birds, Sogdian and Iranian motifs became transformed and received a new interpretation, including ornamentation on the metal parts of belt sets (Smirnov, 1964: 63–64; Tyurk, 2013: 233, 236). This territory had a silver supply in the form of silver Eastern vessels and coins, some of which were probably reused for manufacturing local products (Orbeli, Trever, 1935: 12; Leshchenko, 1976: 188). Today, scholars once again have begun discussing the use of Eastern silver and coins as raw materials, but already relying on the results of studies in the natural sciences (Podosenova, 2016: 15–16). K.A. Rudenko, who analyzed silver items from the Kama region and eastern Urals, which had been traditionally associated with the Volga-Bulgarian circle of silver-making, came to conclusions about the connection of many products with the traditions of the Ugrian world, and existence of highly professional jewelry in the region (Rudenko, 2005/2006: 104–105). Large trade and artisan settlements with jewelry workshops producing goods both for internal and external markets, have been discovered in the western Urals (Perm) (Belavin, Krylasova, 2008: 266; Krylasova, Podosenova, 2015: 41; Podosenova, 2017a: 63). This suggests that the silver belts of the Redikar type were made in such centers.

Tips of belts with representations of the eagle owl and falcon are known from the materials of Birka in Sweden: in female burial 838 one is presented as an amulet (Arbman, 1940, 1943: 311, Taf. 95, 4, 4, a). Several dozen belt plaques turned into pendants have been found in Birka. Some of them are of undoubtedly Magyar appearance (Ibid.: Taf. 95, 1, 3, 8, 9; 96, 3, 7, 12). Researchers of Birka pointed out to the Volga as a route through which “Eastern” belt plaques were transported from the territories of Khazaria and Volga Bulgaria to Scandinavia. I. Jansson found parallels to these items in the materials of the Bolshiye Tigany cemetery on the Lower Kama and linked the appearance of such items in Scandinavia with the Magyar migration to the west in the late 9th century (1986: 84–85, 89). Jansson considered the ornamental décor on the Redikar and Novonikolaevka belt sets a parallel to the ornamental decoration of the tip from burial 838 (Ibid.: 85). C. Hedenstierna-Jonson also considered some plaque-pendants from Birka to be of Magyar origin, but noted that the parallels should be sought outside the habitation area of the Hungarians. According to Hedenstierna-Jonson, these finds mark the movement of the Rus people (“Varangians” in Russian literature) across the expanses of Eastern Europe. These items reflect various intercultural contacts, and plaques turned into pendants indicate the exchange of things, which received new meaning in another reality (Hedenstierna-Jonson, 2012: 31, 41). Similar ideas were voiced by T.A. Pushkina concerning the custom of transforming Eastern belt plaques into pendants, which was observed in the materials from Gnezdovo. She considered such adornments as trophies, which indicate the involvement of their owners in some events in the distant Khazar lands (Pushkina, 2007: 328–329). Notably, belt plaques turned into pendants have also been found in the western Urals (Perm) (Belavin, 2000: 109, fig. 50, 1–8; Belavin, Krylasova, 2012: Fig. 7, 15; 36, 11). Thus, such distances between the places where these belts and their parts were discovered, in our opinion, indicate international contacts in the territory from Scandinavia to the western Urals.

Dating

Antiquities of the Subbottsy type, to which A.V. Komar attributed the Novonikolaevka and Redikar belt sets, are synchronous with the late stage of the Saltovo-Mayaki culture and destruction of the fortified settlements of the Severians in the region of the left bank of the Dnieper. This makes it possible to date these antiquities to the mid 9th to the early 10th century (Komar, 2011: 68–69). The dates of the Boyanovo belt and belt sets from the cemeteries of the Volga Finns somewhat differ from the proposed date of the layer with the antiquities of the Subbottsy type. Thus, burial 279 at Boyanovo is dated to the first half of the 10th century (Belavin, Krylasova, Podosenova, 2017: 2; Podosenova, 2017b: 149). Burials with belt sets from the Middle Tsna region belong to the 11th stage in the relative chronology of the Mordvin cemeteries (Vikhlyaev et al., 2008: 145–147). The chronological position of these burials was established by the adornments of the female complex—syulgams with ends rolled into thin pipes, the length of which was equal to two diameters of the ring (see Fig. 1, 7; 2, 9–11; 4, 7), syulgams with ends bent outward (see Fig. 4, 6), wire bracelets with faceted straight ends, laminar bracelets with ends bent outward (see Fig. 1, 10; 2, 12; 4, 8), and earrings of the Saltov type (see Fig. 1, 9; 2, 8; 4, 5). The absolute date of the 11th stage is confirmed by coins: a Samanid dirham of Nasr bin Ahmad Ash-Shash (914–932) was present at the 2nd Zhuravkinsky cemetery along with laminar bracelets with ends bent outward (Peterburgsky, Vikhlyaev, Svyatkin, 2010: 122–123, fig. 47; Gomzin, 2013: 144), and imitations of dirhams of the 10th century were found in burial 427 of the Kryukovsko-Kuzhnovsky cemetery together with such a bracelet and syulgams (Materialy po istorii…, 1952: 137; Gomzin, 2013: 351). The presence of syulgams, which were typical of the previous stage of the burial grounds (see, e.g., Fig. 1, 8, and also (Vikhlyaev et al., 2008: 144–145)), in the burials with these belts, makes it possible to date the assemblages to the first half of the 10th century.

The remaining set of items from the burials in question does not contradict such a date. According to A.N. Kirpichnikov, combat axe-hammers (see Fig. 2, 6 ) of type 1 were in use in Russia from the 10th to the early 11th century (1973: Fig. 6, 33 ). Among the Mordvins, axes of this type were commonly used in the 9th–10th centuries (Svyatkin, 2001: 39). Such axes are known from the Alanian burials of the 8th–10th centuries in the Northern Caucasus and the Don region (Kochkarov, 2008: 63). At the same time, such axes were also common in the Kama region (Danich, 2015: 74). According to I. Fodor, they were a favorite weapon of the Magyars (2015: 63). Two-partite bits with immovable circular rings, into which smaller movable rings were passed (see Fig. 1, 11 ; 2, 14 ), appeared among the Mordvins in the 7th century and lasted until the 10th century (Sedyshev, 2017: 15, Fig. 7, 5 ). Similar bits are known from the burials of the 8th–10th centuries of the Nevolino and Lomovatovka cultures in the Kama region (Goldina, 2012: 338, pl. 193, 1 , 2 , 4 ; 1985: 238, pl. 31, 21 ), and from cemeteries of the same period in the southern Urals (Mazhitov, 1981: 69, fig. 37, 8 ). Sub-square stirrups with a curved footplate (Fig. 3, 8 , 9 ), which scholars consider to have belonged to the Ugrian antiquities, have been found at Podbolotyevo together with a bridle decorated with plaques of the Redikar type. Such stirrups are known from burial mounds in the southern Urals (Ibid.: 50, fig. 26, 29 ; 81, fig. 43, 8 , 15 ; 152, fig. 74, 2 , 10 ), and from the Bolshiye Tarkhany and Bolshiye Tigany cemeteries on the Lower Kama (on the territory of present-day Tatarstan) (Gening, Khalikov, 1964: Pl. X, 10; Chalikova, Chalikov, 1981: 121, pl. XXXIII, 20). In the 10th century, such stirrups were common among the Hungarians (Révész, 2008: Pl. 19, 21, etc.). Hungarian scholars call stirrups of this type pear-shaped. According to E. Gáll, they are associated with the part of the territory of the Outer Subcarpathia where the “Hungarian conquerors” were present, and go back to the 10th century (2015: 371–372).

Ringed bits with movable large rings and their parallels (Fig. 3, 10 ) were used on the same territories with the stirrups (Mazhitov, 1981: 69, fig. 37, 17; Belavin, Krylasova, 2008: Fig. 172; Goldina, 1985: 238, pl. XXXI, 7). Kirpichnikov attributed such bridle bits to type IV, which was widespread in Eastern Europe in the 10th–13th centuries (1973: 26). In the Outer Subcarpathia region, bits of this type were often combined with pearshaped stirrups (Révész, 2008: Pl. 11, 21, 24, 25).

Thus, belt sets of the Redikar type and similar belts with plaques decorated with the “disheveled” palmette were worn on the territory of the Western Volga region in the first half of the 10th century.

Conclusions

The movement of the Magyars into the territory of their new homeland, according to the recent data, occurred in the 9th century. The belt sets of the Redikar type under consideration and other belts of “Hungarian” appearance emerged in the burial grounds of the Volga Finns a little later—in the first half of the 10th century. Thus, the appearance of these belts among the Volga Finns cannot be associated with the presence of the Magyars, but must have resulted from other processes happening at that time in the western part of the Middle Volga basin.

The mapping of the belts shows that these items are concentrated in the western Urals (Perm). They were most likely made in the same region, which had the needed raw materials, as well as trade and artisan centers with jewelry workshops. The items under consideration could have reached the territories far to the west of the Urals together with precious fur which was transported along the Volga-Kama trade route. Plaque-pendants found in Scandinavian burials (women would wear them as amulet-pendants) and complete belts similar to those appearing at the archaeological sites of the western Urals (Perm) and the Volga region (Arbman, 1940, 1943: Taf. 88, 1 ), as well as torques of the “Glazovo” type, which served as a means of payment for large quantities of goods (Hårdh, 2016) testify to long-distance contacts.

The belts of the Redikar type found in the cemeteries of the Volga Finns should also be viewed in this context. It is difficult to judge whether these items belonged to the people who themselves visited the distant western Urals, or were acquired as tribute to fashion and confirmation of status. However, both in the western Urals (Perm) (Boyanovo and Rozhdestvenskoye cemeteries), Kama region (Bolshiye Tigany cemetery) and in the habitation area of the Volga Finns, such items have been discovered in military burials. Together with other items, belts of precious metals were meant to emphasize the high status of such burials.

Identification of such burials makes it possible to better understand the processes of engagement of the population stretching from the Baltic region to the Ural Mountains into international trade, social stratification, as well as conditions for the emergence of early state institutions at the turn of the millennia. It is noteworthy that the presence of militarized mobile groups is observed on the territories whose population played a key role in social and political processes of the time. One such territory at the turn of the millennia was probably the area in the basin of the Middle Tsna River on the northeastern border of the Khazar Khaganate.