“Blue Economy”: Evolution of the Concept and Prospects for the Russian Arctic

Автор: Sbojchakova A.V., Branitskaya N.A., Bliznyakova S.S.

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Social and economic development

Статья в выпуске: 61, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The “blue economy” is a popular concept for the development of marine economic activity, implying social and environmental responsibility of its subjects. Key international actors present their strategies and use the “blue economy” as an area of international cooperation. The Russian Federation, despite its national interests related to both the development of the world ocean and the development of the Russian Arctic, does not have the “blue economy” strategy. The purpose of this study is to demonstrate the prospects of the “blue economy” for the Russian Arctic. The article describes the origin and evolution of the concept in the international arena and identifies the features of the conceptualization of terminology in the academic environment. The discrepancy in the interpretations of the “blue economy” in both political and scientific discourse is noted. An analysis of the approach to the “blue economy” in key Russian doctrinal documents showed that they enshrine the key measures for the development of the concept. This thesis was confirmed in the course of studying economic processes in the Russian Arctic. The authors point to the promising nature of conceptualizing the Russian approach to the “blue economy” and its doctrinal consolidation. The results of the study can be used as analytical material, as well as for academic purposes — to create an empirical basis for further scientific work on the selected and related topics.

Blue economy, AZRF, concept, strategy

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148332686

IDR: 148332686 | УДК: [338.47:339.92](985)(045) | DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2025.61.71

Текст научной статьи “Blue Economy”: Evolution of the Concept and Prospects for the Russian Arctic

DOI:

At the turn of the 20th—21st centuries, the global community faced several structural economic crises. The process of globalization polarized uneven economic development, and international organizations emphasized the need for a comprehensive approach to managing crises while maintaining living standards and continuing intensive development. At the same time, the politicization of the environmental agenda led to a discourse on the need to take into account the environmental component of global economic issues.

∗ © Sbojchakova A.V., Branitskaya N.A., Bliznyakova S.S., 2025

This work is licensed under a CC BY-SA License

The first attempt to synthesize economic stability, implying symbiosis with environmental and social components, was the concept of sustainable development, which was published in a report by G.H. Brundtland in 1987 1. Despite the popularity of the concept of sustainable development, alternative approaches have emerged, characterized by different definitions of the object and methodology. The Blue Economy concept, which was developed in response to the growing importance of the world’s oceans and the economic, social and environmental challenges of their development, is one of such examples.

The purpose of this study is to reveal the potential of this concept for the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation. This study presents a historical retrospective of the origins and evolution of the Blue Economy concept in the international arena, demonstrates its conceptualization in the academic community, characterizes the Russian understanding of the Blue Economy in strategic documents, and identifies the prospects for the Blue Economy in the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation.

The study is based on open empirical data and sources, which are divided into several groups, including statistical data, materials from international organizations and government documents, scientific literature on the issue under study, as well as media and news agency materials. Using an ecosystem approach, where all parts of the ecosystem are closely interconnected, the authors identify the water areas and coastal territories of the Russian Arctic as the object of the Blue Economy. The authors understand the Blue Economy of the Russian Arctic as the sustainable economic development of the water areas and coastal territories of the Russian Arctic.

Origin of the concept and approaches to defining the Blue Economy in the international arena

The need to define a legal framework for the use of the world’s oceans at the international level was first considered in 1982, when the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea was adopted. Ten years later, the Conference on Environment and Development was held in Rio de Janeiro, where the need for sustainable management of marine resources was reiterated. However, this was rather declarative in nature and did not involve the development of a relevant concept for the competent use of the world’s ocean resources.

In 2009, entrepreneur and scientist G. Pauli presented a report 2 to the Club of Rome outlining the economic theory he had developed. The idea was that in a circular economy, all materials, including wastes, are used in production. G. Pauli’s methodology was based on the observation of natural processes, so his model assumes an analogy with the natural functioning of ecosystems, where the residual product arising at the end of one cycle becomes useful for the functioning of another. This scheme leads to the rationalization of resource use and the elimination of problems with the disposal of possible associated waste. The goal of G. Pauli’s economic cycle model was to generate economic profit, but an important advantage of this model would be the environmentally safe use of natural systems and the availability of the final product to consumers [1, Zhilina I.Yu., pp. 18–19].

-

G. Pauli’s concept, which he had been developing since the early 1990s with the direct participation of the UN [2, Krivichev A.I., p. 10], was received positively: following the 2012 UN Conference on Sustainable Development, a document was adopted 3, defining the Blue Economy as an innovative model of sustainable development, particularly relevant for coastal countries and small island states. However, the interpretation of the concept by global political actors varied significantly depending on national characteristics, level of economic development, and geopolitical interests.

In September 2015, the concept was formally presented in the UN General Assembly resolution “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, which included 17 UN global sustainable development goals. The Blue Economy concept is part of Goal 14, “Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development” 4.

In early 2021, the UN General Assembly tasked UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission with becoming the coordinating institution for the Decade of the Ocean, an initiative that provides an opportunity for interaction and cooperation in the interests of sustainable development of the world’s oceans. This program includes activities aimed at bringing together resources, world governments, businesses, NGOs and civil societies to gain scientific knowledge and develop partnerships necessary to support a functioning, productive, viable and sustainable ocean 5. However, the official website of the Decade of the Ocean hardly mentions the concept of the Blue Economy, which is inextricably linked to more than just water resources development. This suggests a certain caution in the use of the term, which can probably be explained by the vagueness of its interpretation.

A sustainable Blue Economy is discussed by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), which notes the importance of coordinated policies across environmental, social, and economic spheres by all countries to further sustainable development 6.

In 2022, at the UN Conference to Support the Achievement of Goal 14, the term “Blue Economy” was, by contrast, regularly mentioned by state representatives in their reports, demonstrating its international adoption and continued development. Representatives from Namibia, Palau, Tanzania, Tonga, São Tomé and Príncipe, Timor, Angola, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, and Equatorial Guinea identified the development of the Blue Economy as a priority for their countries and expressed their willingness to provide support for marine preservation and combating piracy. Representatives of Portugal expressed the need to create a “Blue Economy Hub”, which would significantly increase the number of state-funded startups in this area 7.

A World Bank report (2017) defines the Blue Economy as “joint actions by states aimed at promoting economic growth, social integration and the preservation of the environmental sustainability of oceans and coastal areas” 8. It is important to note that the report pays particular attention to small island developing states and least developed coastal countries, although nation states are identified as the actors for cooperation across all aspects of the Blue Economy.

The World Bank report identified five types of marine activities that define areas of responsibility for the Blue Economy, namely:

-

• harvesting and trade of marine living resources;

-

• extraction and use of marine non-living resources (non-renewable);

-

• use of renewable non-exhaustible natural forces;

-

• commerce and trade in and around the oceans;

-

• indirect contribution to economic activities and environments 9.

The World Bank also identifies the following components necessary for the successful implementation of the blue economy concept:

-

• provide social and economic benefits for current and future generations;

-

• restore, protect, and maintain the diversity, productivity, resilience, core functions, and intrinsic value of marine ecosystems;

-

• be based on clean technologies, renewable energy, and circular material flows that will reduce waste and promote recycling of materials 10.

The ocean is described as a “new economic frontier, a source of resource wealth and great potential for boosting economic growth” in the 2016 report “The Ocean Economy in 2030” 11 by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The term “Blue Economy” is rarely mentioned in the title or the text of the document, although the report emphasizes the need to use the ocean’s potential wisely and to find sustainable approaches for its further development. The authors of the report point out that the terminology relating to the economy of the seas and oceans varies from country to country. For example, the concept of the ocean economy is typical of

Ireland and the United States, while the concept of the sea economy is widely used in Australia, Canada, the EU countries, New Zealand and the United Kingdom 12.

The OECD divides Blue Economy sectors into traditional (fisheries, shipping and port infrastructure, marine construction and shipbuilding, marine and coastal tourism) and emerging (marine biotechnology, renewable energy, deep-sea mineral resource extraction). According to OECD estimates, by 2030, the global ocean economy could double its contribution to global GDP, reaching over $3 trillion 13.

The European Union (hereinafter referred to as the EU) has become one of the world’s leading centers for the development and implementation of sustainable circular economy models. The significance of its experience is explained by its leading position in the global climate agenda and its active development of strategic documents aimed at supporting the Blue Economy. The growth of the Blue Economy is predicted primarily in the EU member states [3, Yasser M.M., Halim Y.T., Elmeg-aly A.A.].

The first EU “maritime” documents aimed at sustainable water resource management and the development of sustainable maritime strategies by member states were the Integrated Maritime Policy 14 and the EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive 15, adopted in 2007 and 2008, respectively. In 2012, EU documents identified five drivers of Blue Economy growth and introduced the term “blue growth” 16; in 2014, the Marine and Coastal Spatial Planning Directive was adopted 17.

In 2018, the Blue Economy was defined by the European Commission as “maritime activities that use and/or produce products and services, as well as maritime activities, including seafood processing, marine biotechnology development, shipbuilding and repair, port activities, and communications” 18.

The further evolution of the EU’s approach to defining the concept of the Blue Economy can be traced in a number of key strategic documents: the European Green Deal 19, a strategy for achieving climate neutrality by 2050; the Circular Economy Action Plan 20, which optimizes resource use, minimizes waste, and develops recycling technologies; and the European Climate Law 21, which contains binding targets to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 55% by 2030 and achieve climate neutrality by 2050. Under the auspices of the European Commission, the Blue Economy Report is published annually 22, which includes indicators of the socio-economic performance of blue economy sectors, their contribution to the EU economy in terms of turnover, added value, operating surplus, and job creation. According to the definition presented in the report, the Blue Economy is “economic activity related to the use of the resources of the oceans, seas, and coastal zones, including fisheries, aquaculture, marine resource extraction (oil, gas), offshore wind and ocean energy projects, desalination, shipping and marine tourism, as well as a wide range of related services (seafood processing, shipbuilding, port activities, marine biotechnology, insurance, and monitoring)” 23.

In 2021, the European Commission adopted a new approach to developing a sustainable Blue Economy, which identified objectives in terms of spatial planning, decarbonization, biodiversity restoration, science and technology development, application of circular models and solutions, improving the sustainability of food systems and coastal areas, as well as promoting employment and professional skills development 24.

Today, the concept of the Blue Economy is expanding beyond the generally accepted understanding of exclusively maritime activities, becoming a global economic project in which participation is essential for both developed and developing countries, as well as international organizations, NGOs, and civil society.

Thus, approaches to the Blue Economy have evolved from general management to more detailed strategies integrating the economic, environmental, and social aspects of the sustainable use of marine resources. The global community recognizes the need for synergy between economic growth and environmental protection. This synergy enables countries to achieve sustainable development goals in the face of global environmental challenges.

Green Economy vs. Blue Economy

In the context of global environmental and socio-economic challenges, the concepts of the

Green Economy, already accepted by the global community, and the rapidly developing Blue

Economy are becoming increasingly important. Let us consider the main characteristics of these concepts and present them in a comparative table.

Table 1

Green Economy vs. Blue Economy

|

Green Economy |

Blue Economy |

|

|

Formation period |

1989–2000 |

2009 – present |

|

Main goal |

Achieving sustainable development by reducing pressure on natural systems and resources, implying a balance between economic development, social progress and environmental protection |

Achieving sustainable development of marine and coastal areas, ensuring long-term economic growth and employment from marine resources while maintaining the sustainability of marine ecosystems |

|

Scale |

Global |

Regional |

|

Key priorities |

•Reducing the carbon footprint •Energy efficiency, development and implementation of renewable energy sources •Sustainable resource management and greening all sectors of the economy |

•Preservation of marine ecosystems (corals, fish stocks) •Combating ocean pollution •Development of marine-related sectors (fisheries, aquaculture, maritime transport and tourism, renewable energy) |

|

Target economic sectors |

•Energy (including renewable energy) •Sustainable agriculture and forestry •Green transport •Waste management (recycling) •Ecology |

•Fisheries and aquaculture •Maritime transport and transport infrastructure (including green ports) •Coastal and marine tourism •Marine renewable energy •Marine biotechnology and pharmaceuticals |

Based on the data presented in the table, it can be concluded that the Green and Blue economies are not competing, but rather complementary strategies for achieving the SDGs. The Green Economy sets the general framework for greening all sectors and reducing anthropogenic pressure on the biosphere, while the Blue Economy represents a narrow application of these principles to a unique and critically important environment — oceans and coastal zones — focusing on the sustainable use of their resources and ecosystem services.

In addition, there is synergy between the Blue and Green economies, as the “greening” of marine sectors directly contributes to the achievement of decarbonization goals. At the same time, “healthy” oceans are a global climate regulator and a source of biodiversity, which is critical for the overall sustainability of the planet.

In terms of key differences, we can talk about varying objectivity. The Green Economy aims to transform all land and marine economic systems globally to reduce their overall environmental footprint (carbon, resource, pollution), while the Blue Economy focuses on managing a specific environment — the oceans — with their specific ecosystems, resources and traditional maritime activities.

Conceptualization of the Blue Economy in academic circles

Despite growing attention to the potential of the Blue Economy, uncertainty remains both in its conceptualization and approaches to its implementation. The Blue Economy generally refers to the management of water resources and the marine ecosystem. However, there is still no single definition or unified classification for this concept in scientific discourse that would include all the “blue” aspects under consideration and allow for the measurement of quantitative and qualitative indicators.

A number of recent studies point out that, despite a clear definition of the components of the Blue Economy, the concept is difficult to separate from the long-established concept of sustainable development [4, Singh R., Kumar P., 5, Germond-Duret C.]. Nevertheless, the conceptual framework outlined by R. Singh and P. Kumar is useful for structuring the analysis of current practices and identifying the missing elements necessary to achieve sustainable ocean development. The complementarity and synergy of the Blue Economy and the concept of sustainable development are indicated by the results of a review of articles published in Web of Science from 2014 to 2023, conducted by M. Keen, A. Schwartz, L. Wini-Simeon [6].

The concept of the Blue Economy is associated with any economic activity that uses ocean resources. A bibliometric analysis of the concepts of Blue Economy, marine economy, ocean economy, and blue growth, conducted by R.M. Martínez-Vázquez and co-authors highlights the interconnection between the concepts of Blue Economy and Blue Growth: in order to achieve the necessary results of the Blue Economy, it is necessary to create alliances between Blue Growth sectors [7]. P. Tripathi, S. Kapoor, and S. Alavi define the Blue Economy as the sustainable use of the world’s ocean resources, based on the principles of environmental sustainability [8]. This thesis is confirmed by the fact that such an economy includes various types of ocean-related activities: from harvesting marine living resources to offshore energy.

Studies devoted to the applicability of the Blue Economy to the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation also identify the Blue Economy of the Arctic as an economy of the sea [9, Druzhinin A.G., Lachininskii S.S.] or see it as a tool for sustainable development, noting the need to develop government and business projects [10, Kokurina A.D., Monastyrskiy D.I.], focused on the Arctic sea area, the development of shipping and seaports, decarbonization, further digitalization, the use of new technologies and the creation of sustainable supply chains [11, Krivichev A.I., Nyudleyev D.D., Sidorenko V.N., pp. 415–424]. G. Tianming and co-authors note that the Russian Arctic is characterized not only by its marine economy, but also by a number of coastal activities related to the sea (aquaculture, shipping, offshore oil and gas production, etc.) or affect marine bioenergy (e.g., reduction of emissions into the coastal atmosphere and water, waste management, coastal tourism, creation of nature reserves and parks, etc.) [12].

Blue Economy in the AZRF: the Russian perspective

Russia’s seas cover approximately 8.6 million km2, which is 2.4% of the world’s oceans, with the Arctic waters covering 6.8 million km2 25, demonstrating the potential of the Blue Economy concept (and future strategy) for Russia. However, despite the noted [9, Druzhinin A.G., Lachininskii S.S., pp. 336–348] increase in the priority of developing the maritime economy in the Russian Federation, no strategic document defines or mentions the term Blue Economy. Therefore, the presence of individual Blue Economy measures in Russia’s conceptual documents deserves more detailed consideration.

The Maritime Doctrine of the Russian Federation (hereinafter referred to as the Doctrine) and the Strategy for the Development of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation (hereinafter referred to as the Strategy) were selected for the analysis of the presence of blue economy components. The criteria for analyzing the level of conceptual development of the Blue Economy will be the compliance of the measures in the documents under review with the definitions, classifications, and development directions of the Blue Economy of leading international actors presented in the section. The units of analysis and comparison of strategic documents were the presence of a definition of the Blue Economy concept, the presence of an environmental component of the Blue Economy in the strategies (measures to eliminate accumulated damage to ecosystems, to preserve biodiversity, to reduce negative impacts on the ecosystem), the economic component (measures to create/improve innovative development sectors, including investments in scientific research into new technologies for the industries of the marine and coastal economy, measures to create new jobs and increase employment in the maritime sector), and the development of commercial infrastructure.

Table 1 demonstrates that both the Strategy and the Doctrine aim to integrate economic incentives for development and consideration of environmental aspects of industrial process management. Both the Strategy and the Doctrine are distinguished by a comprehensive approach to the implementation of state policy through synergy in the development of marine and coastal areas.

At the same time, the Strategy clearly emphasizes the need to maintain a balance between economic development and environmental sustainability in the region, as evidenced by the inclusion of measures to reduce environmental impacts. Thus, the Strategy highlights the preservation of the traditional way of life of indigenous peoples, the need to develop renewable energy sources, measures to adapt to climate change, and the creation of specially protected natural areas [9, pp. 336–348] as key priorities, which is consistent with the first and second components of the successful development of the Blue Economy, according to the World Bank. Furthermore, the Strategy’s economic objectives for maritime and coastal activities include: state support for small businesses, private investment in projects related to the Northern Sea Route, further development of natural resources, fishing sector and fish production. Despite the Strategy’s obvious focus on sustainable development, it establishes a “special economic regime for the transition to a circular economy” for the maritime area, which is an important feature of the Blue Economy, according to the EU definition.

The Russian Federation’s Maritime Doctrine defines maritime activities as “activities aimed at studying, developing and using the World Ocean in the interests of sustainable development and ensuring the national security of the Russian Federation” 26. This definition is close to the EU’s approach to the Blue Economy, as set out in the European Commission’s 2021 framework document. According to the OECD classification, the Doctrine specifies innovative sectors of the Russian maritime economy (development of renewable energy sources (hereinafter referred to as RES), aquaculture, and mariculture) and declares an innovative focus on the development of “old” industries (development of maritime transport, port infrastructure, all types of fleet, etc.). The development of RES corresponds to the third component of the successful development of the Blue Economy, according to the World Bank. The Doctrine’s measures, such as the development of state environmental monitoring systems, mandatory environmental insurance for maritime transport, and response to damage to water bodies and bio-resources, correspond to the second component of the Blue Economy, according to the World Bank. Only the social component is developed to a lesser extent in the Doctrine.

Thus, an analysis of doctrinal documents aimed at developing Russia’s maritime and coastal Arctic territories revealed that, although the Blue Economy concept is not defined or formally enshrined in the Russian Federation’s strategy, it nevertheless includes most of the components of Blue Economy development.

Table 2

Blue Economy in Russian Federation doctrines

|

Maritime Doctrine |

Strategy for the Development of the AZRF |

|

|

Definition / reference to the Blue Economy |

No |

No |

|

Ecological component |

||

|

Measures to eliminate accumulated damage to ecosystems |

Maritime transport: a system of compulsory environmental risk insurance |

Identification, assessment, and organization of the elimination of accumulated damage to the environment |

|

Measures to conserve biodiversity |

Monitoring threats and responding to damage to water bodies and bioresources, compliance with fisheries requirements for offshore marine activities; |

Creation of specially protected natural areas |

|

Measures to reduce negative impacts on the ecosystem |

“An integrated approach to the development of state environmental monitoring systems for coastal territories, |

Development of a unified system of state environmental monitoring, including hydrometeorological monitoring; minimization of harmful |

26 Maritime Doctrine of the Russian Federation. URL: (accessed 08 December 2024).

|

territorial seas, exclusive economic zones, and the continental shelf” 27 |

atmospheric emissions and discharges into water bodies; assessment of the consequences of environmental impact; regular assessment of the impact of nuclear energy on the environment; improvement of the waste management system |

|

|

Economic component |

||

|

Measures to create (improve) innovative development sectors (investments in scientific research of new technologies for marine industries) of the marine and coastal economy |

Innovations in the fisheries industry, electric power (tidal, wind, thermal, and biomass energy); development of marine research and innovation centers; “implementation of new technologies using marine bioresources, aquaculture, construction of fishing vessels, and application of new bioresource reproduction technologies” 28; innovations in shipbuilding and cartographic production |

A special economic regime for the transition to a circular economy, the development of knowledge-intensive and high-tech industries, the development and implementation of engineering solutions for infrastructure operation in the face of climate change, and a “state support mechanism for projects to improve the efficiency of electricity generation in isolated and hard-to-reach areas” 29 |

|

Providing new jobs and increasing employment in the maritime sector |

An increase in the number of jobs in the field of aquatic bioresource research and shipbuilding is projected |

A gradual increase in the number of jobs at new enterprises in the AZRF, a reduction in the unemployment rate by 0.2% by 2035. |

|

Commercial infrastructure |

“Renewal of maritime infrastructure assets, development of icebreaker and research fleets, modernization of the Arctic port network; infrastructure of coastal processing plants; development of port infrastructure (construction and reconstruction of railways)” 30 , highways, and modern transport and logistics centers |

“Comprehensive development of seaport infrastructure and shipping lanes in the waters of the Northern Sea Route, the Barents, White, and Pechora Seas; construction of nuclear-powered icebreakers; construction of hub ports and the creation of a Russian container operator for international and cabotage shipping along the NSR” 31; Expanding navigation capabilities on rivers and canals, dredging, and developing ports and port terminals; Construction (reconstruction) of airport complexes |

Prospects for the “Blue Economy” in the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation

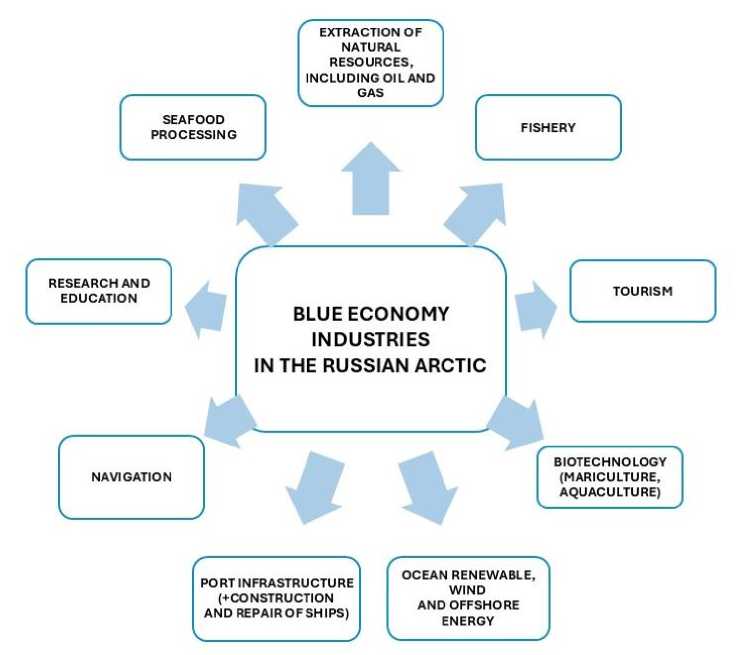

The authors consider the Blue Economy of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation as the comprehensive development of maritime and coastal economies. To illustrate the potential and prospects of the Blue Economy in the AZRF, it is necessary to describe the development of the maritime and coastal economic sectors. The Blue Economy sectors in the Russian Arctic include both traditional and emerging industries (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Blue economy sectors in the AZRF (compiled by the authors).

The Northern Sea Route is a key shipping project in the AZRF. Its potential for economic development lies in the potential increase in Russia’s share of global cargo transit and budget revenue 32, the attraction of foreign investment, and the creation of new jobs. According to statistics, 2023 was the peak year for cargo transportation (36.254 million tons) 33, and shipping volumes are expected to grow, along with ports’ capacity 34. The development of the NSR is associated with the intensification of work in the field of port infrastructure, shipbuilding and cargo repair, as well as work on deepening the seabed, which are planned in the NSR Development Plan until 2030 35 and cover several sectors of the Blue Economy. According to this Plan, shipping volumes will increase to 110 million tons by 2030, creating 35,000 new jobs 36.

Despite strict compliance by vessels navigating the NSR with the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships 37 and the Polar Code 38, which require the prevention of marine pollution, researchers point to some legislative shortcomings [13, Bhagwat D., p. 20], as well as the risk of pollution “as a result of accidents or crew negligence” [14, Baghdasaryan A.A., p. 20]. Therefore, increasing shipping volumes on the NSR opens up opportunities for Russia to conceptualize and formalize a Blue Economy, which involves the implementation of new technologies with greater environmental sustainability potential 39. One of the possible solutions could be the introduction of LNG-powered vessels (for example, the Arktika icebreakers), which would reduce SO 2 emissions by 90% and NO 2 by 85% compared to diesel-powered ships 40.

The development of the NSR is closely linked to the extraction of oil, gas, and other natural resources in Arctic waters. The AZRF development strategy in this area does not separate offshore resource extraction from onshore production and prioritizes, until 2030, “the development of new solid mineral deposits and hard-to-recover hydrocarbon reserves, increasing deep oil refining capacity, producing liquefied natural gas and gas chemicals, and the beneficial use of associated petroleum gas” 41. Russia has the largest hydrocarbon reserves in the Arctic: natural gas reserves amount to 55 trillion m3, and oil reserves — 7.3 billion tons (75% and 23.5%, respectively) of Russia’s total reserves 42.

The Arctic shelf is becoming the most promising area for energy resource exploration [15, Fu S., Malashenkov B.M., p. 403], where the large-scale Prirazlomnaya project is being implemented. Among the promising offshore deposits, gas, oil, oil and gas condensate fields are located on the Barents shelf and in the waters of the Kara Sea 43. The main task of the extractive industry in line with the Blue Economy concept should be to include “ensuring fairness, security, and the preservation of natural capital” in the measurement of success ratio, along with economic indicators [1, Zhilina I.Yu., p. 27].

Arctic fisheries, like the development of the NSR, are at the intersection of old and new sectors of the Blue Economy. At a conference on aquatic biological resources, held in Arkhangelsk in 2023, the head of the Federal Agency for Fisheries noted that “the fish catch in the Arctic amounted to more than 500,000 tons — more than 10% of the total Russian catch” 44. Fishing is prohibited in the open part of the Arctic Ocean 45, so Russian Arctic fisheries are limited to a 200-mile economic zone, with the most regular fishing taking place in the Barents Sea [16, Dusayeva E.M., pp. 29–46]. In order to maintain the Barents Sea cod stock at the 880,000-ton TAC level, it is advisable to refer to Norway’s experience in managing fish stocks, as the introduction of scientifically based quotas has increased the cod population by 40% over 10 years (2010–2020) 46.

At the same time, climate change, water pollution, and depletion of fish stocks require innovations in Arctic fishing technology, including the construction of fish processing plants, the development of trawling fleets, the advancement of biotechnology, modern mariculture (aquaculture).

The development of renewable energy sources is also promising for the Arctic. Currently, energy supply in the Arctic is provided by traditional sources, but due to geographical remoteness, high costs and the complexity of implementation in northern conditions, it has not been possible to achieve universal coverage of all remote Arctic territories. A partial solution to the problem is the development of renewable energy sources. Their potential is the possibility of creating closed energy systems, minimizing environmental damage and the risks of technological disasters. The experience of developing solar power plants in Yakutia has also shown significant budget savings (35 million rubles per year), replacing 20% of diesel generation [17, Sokolov A.N., p. 11]. Due to weather conditions, the Arctic has high potential for wind, wave, and geothermal energy. However, the development of these renewable energy sources is associated with a lack of necessary technologies and a shortage of personnel. Both of these types of renewable energy sources are seasonal in nature, which means that they can only be used in combination with traditional sources. At the same time, Norway’s experience shows that it is possible to provide 98% of the Arctic’s energy balance using renewable energy, including hydropower 47.

The inclusion of nuclear energy in renewable energy sources is controversial 48 and is a topic for separate research. Russia possesses closed nuclear fuel cycle technologies, which make it possible to reduce environmental damage to zero [17, Sokolov A.N., p. 12]. The Rosatom State Corporation has already begun implementing the floating nuclear power plant project (Port of Pevek) 49 and plans to replace outdated and expensive energy sources with similar projects. In general, the concept of the Blue Economy implies self-sufficiency and a closed energy cycle, which will be facilitated by the development of renewable energy sources in the Arctic. The complete replacement of traditional sources with renewable energy sources is a long-term prospect. The example of renewable energy sources demonstrates the Blue Economy in action: in the near future, renewable energy sources will contribute to the energy transition and, consequently, to reducing the burden on the environment, which will contribute to the conservation of resources. In social terms, renewable energy sources will improve the quality of life of the Arctic population and create jobs. From an economic perspective, renewable energy contributes to budget savings and infrastructure development.

Arctic tourism is a developing potential area of the Blue Economy, aimed at promoting the historical, cultural and natural potential of the Arctic 50. As a result of the analysis, V.Yu. Zhilenko identified the following strengths of Arctic maritime tourism: promoting the development of science and technology, ensuring environmental safety, comprehensive management of marine and coastal areas, developing eco-tourism, attracting investments, creating public-private partnerships, etc. [18, Zhilenko V.Yu., p. 154]. The main problems, hindering marine and coastal tourism in the Western Arctic, are low awareness and attractiveness [19, Grushenko E.B., p. 29]. The general problems of tourism in the Arctic, as identified by respondents to a survey of polar explorers, can be applied to marine tourism: inadequate infrastructure, lack of tourist cashback in the AZRF, and poor information support 51. Scientific studies also point to the need to organize transport corridors to areas of increased tourist interest, including through water transport as a means of organizing river and sea cruises [20, Tsvetkov A.Yu., p. 241]. Infrastructure issues are already a matter of national interest, and potential tourists will attract investors who are capable of accelerating positive infrastructure changes. Solving these problems and developing tourist routes, including along the Northern Sea Route, will stimulate economic growth while preserving the stability of the marine ecosystem.

Despite the significant potential of the Blue Economy for the sustainable development of the Russian Arctic zone, its implementation is associated with a range of risks that require systematic management. Let us consider three key categories of challenges: ecological, social, and economic.

Table 3

Risks to the development of the Blue Economy concept in the AZRF

|

Ecological |

Social |

Economic |

|

|

|

A possible solution for minimizing ecological risks could be the introduction of an environmental reserve mechanism, which would involve allocating 15% of revenues from the NSR to a fund for the rehabilitation of Arctic ecosystems. Regarding social challenges, preserving the traditional way of life of the indigenous peoples of the North requires the introduction of mandatory ethnological expertise for projects, with veto rights for indigenous communities to protect and represent their interests. To overcome economic risks, it is necessary to introduce differentiated taxation for large Arctic companies, for example, by reducing the mineral extraction tax for renewable energy projects. Furthermore, a mechanism of green state guarantees for the financing of Arctic start-ups in biotechnology and hydrogen energy could become a key tool.

Undoubtedly, implementing the Blue Economy concept in the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation requires significant socio-ecological-economic transformation, which entails the development and adoption of appropriate legislation, the implementation of effective mechanisms for sustainable management, and the formation of a unified Arctic technology cluster for the development of compensation solutions.

Conclusion

The authors’ analysis of scientific literature and the Blue Economy definitions from international organizations demonstrates that there are several approaches to interpreting the concept of a Blue Economy, which can be divided into three groups. The first approach focuses on the fact that the Blue Economy is an integral part of the concept of sustainable development, which details the methodology by identifying the world’s oceans as a reference object. The second approach does not consider the concept of the Blue Economy to be a qualitatively new phenomenon and refers to it as the Green Economy applied to global waters. The third approach, also characteristic of the EU, is based on the idea that the Blue Economy refers to any economic activity related to the economic development of the resources of the world ocean and its coastal zones.

The multiplicity of definitions and approaches to the Blue Economy in the international arena demonstrates, on the one hand, a lack of consensus on which industries are new or traditional, and which reference objects the concept is aimed at: should only water areas or coastal territories associated with maritime activities also be included in the concept of the Blue Economy? On the other hand, it is clear that the Blue Economy implies the implementation of a comprehensive strategy aimed at conserving resources, restoring ecosystems and transitioning to new technologies.

The Russian Arctic and maritime doctrinal documents do not mention or define the Blue Economy. However, all economic sectors related to the Blue Economy in one form or another are developing in Russia with varying degrees of success. The goals set by the doctrinal documents are fully consistent with individual development areas and the Blue Economy. Furthermore, there is a clear complementarity between the sustainable development of the Russian Arctic and the Blue Economy.

A study of economic processes in Russia’s northern territories demonstrates the de facto development of Blue Economy sectors. Many of these projects are promising in terms of their contribution to the national economy. Furthermore, the potential of the blue economy as a circular economy, independent of external resources and capable of full self-sufficiency, is of undoubted interest for the Russian Arctic. The authors believe that, if Russia’s approach to the Blue Economy is conceptualized and doctrinally enshrined, it could become a driver for the development of the key Russian Arctic project, the Northern Sea Route, and the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation as a whole.

Considering the potential and strategic development vector of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation, it can be predicted that by 2035, the AZRF’s contribution to Russia’s GDP will tend to grow from 3% to 7% due the increase in maritime logistics, the launch of LNG projects and the development of renewable energy technologies, as well as the implementation of sustainable development concepts. This makes the Arctic a territory of balanced development, where economic efficiency is combined with environmental responsibility and social justice.