Body's proportions systems and applications in art and clothing

Автор: Babcinetchi Vladlen

Журнал: Мировая литература в контексте культуры @worldlit

Рубрика: Взаимодействие литературы и других видов искусства. Литературное произведение и иллюстрация

Статья в выпуске: 6, 2011 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147228160

IDR: 147228160

Текст статьи Body's proportions systems and applications in art and clothing

IntroductionPlastic art and proportions systems

In the plastic art, the human figure has various means of representation. These means differ depending on the period of time, technique or the reason why the work was executed. The artists have always been preoccupied with the problem of the human body’s proportions. Meanwhile, sciences as medicine, anatomy, and mathematics bring new visions of the human body, which by connection, form the whole picture/ complete assemble of the human body. Therefore it is commonly believed that the study of the human figure knows two possible means of representation: the artist’s interpretation and the scientist’s vision. Both visions equally represent

genuine forms of knowledge. The artist, having the tendency to interpret the reality, is aware that his creations are subdued to personal interpretations by the viewer. On the other hand, the scientist, interested in findings and objective discoveries, is convinced that his work will be seen as it is. By studying the proportions, artists use the scientists’ methods, which come from rational interpretations, and try in the same time to obey certain preestablished rules.

In time, the human society is faced with continuous changes, and in the same time art, science and the working methods develop. Once the rules were set, it was clearly that they could not satisfy the need of knowledge of every artist, each and every one of them being promoters of a certain culture and period of time. Moreover, the characteristics of a developing (growing) body can be described and reproduced by a series of standard formula; nevertheless, these are subdued to a general characteristic which is subject to interpretation. Antic Egypt’s, Greece’s, Middle Ages’ or Renaissance’s proportions’ systems are as different as the art of each period. We can admit today that the knowledge area reunites the accuracy of mathematics and the freedom of artistic creation. The ‘history of proportions’ study represents the reflection of the history of style’ (Ervin Panofski). The evolution of proportions’ system is strictly linked to mankind’s evolution.

Stylization alternatives of the human figure

From an aesthetic point of view, for the modern civilization, the characters of the cave paintings, African sculpture, Rubliov’s icons, Michelangelo’s work or Salvador Dali’s are situated on the same scale of value, being equally accepted as important points of reference in characterizing the spiritual evolution of the human civilization. Starting from hieroglyphs or primary geometrical figures, the human figure is represented in many ways, more or less realistic, full of symbolism or being just the expression of the creative side of the artist. Stylization is a procedure of simplifying, being limiting and high handed, by reducing to its’ essence an image or a shape, but keeping in the same time its’ specific features, plays an important role in the determination process of the characteristic features of the represented pattern. This process is used to emphasis or sometimes even exaggerate certain features, with the purpose of transmitting a specific message, idea or impression to the beholder. It is commonly accepted that plastic art, throughout history, has played an important role in what concerns transmitting an image through sight, fact that can be compared today with television or internet. This fact can constitute in itself a reason why humans’ image finds numerous interpretations, being influenced by the way it is represented and the message that carries through attitude and expression.

Versions of stylization of the human body

-

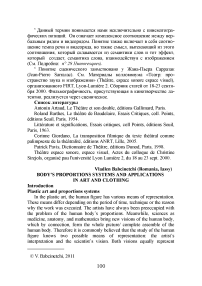

- David by Michelangelo [Fig .1] is a true example of realistic interpretation of the human figure. Iris portrait being a model for the study of proportions.

-

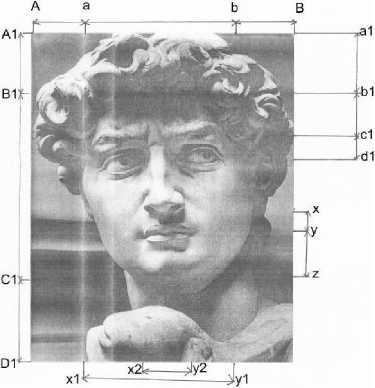

- Senecio [Fig.2] by Paul Klee represents an eloquent stylization model of the human face; it is made by using a series of geometrical fonns and proportions which have as origin the gold section. The expressivity of the portrait is accentuated through the grating chromatic as well as through eyes’ positioning and the unusual proportion between head’s fonn and the dimensions of the other elements of the face.

-

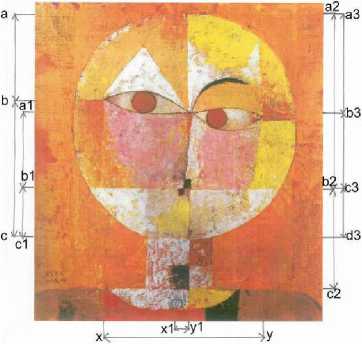

- In a period close to the one of Michelangelo’s, but in a different geographic area and in a different manner. Rubliov creates a masterpiece of Byzantine painting, the portrait of the Savior [Fig.3]. By studying the icon’s proportions, we can observe the elongation and stylization of the face, emphasizing the spiritual nature of the face.

Fig. 1. Michelangelo. David (detail)

AB - head’s width that also includes hair’s volume

Al - the maximum point of head’s height

Bl - the maximum point of face’s height

Cl - the base of the chin

DI - the base of the neck

-

XI. yl - the width of the face at cheeks’ level

X2. у2 - the length of the mouth cl - eyebrows’ axis dl - eyes’ axis x -base of the nose у - mouth’s axis z - chin’s axis

Fig.2. Paul Klee. Senecio

ab/bc; albl/blcl;

а2Ь2/Ь2с2 - the gold ratio a3b3/b3c3/c3d3 - Le

Corbusier’s modulator xy - face’s width at

eyes’ level xlyl - mouth’s width

Fig.3. Rubliov. The Savior

А1В1 - hair’s height

B1C1 - face’s height

D1E1 - neck’s height cl - eyebrows’ axis dl - eyes’ axis x-nose’s axis у - mouth’s axis z - chin’s axis

The relationship between the base line network, clothes and body’s proportions.

The clothing creation, in order to be practical an aesthetic in the same time, means knowing the basic notions regarding the human body. Creating a given piece of clothing means to achieve the right proportions, these being different and related through linear dimensions, of surfaces, volumes, the specific of textures and colors. Each model can be characterized by the bonding or the difference of the elements mentioned. When realizing a costume/ suit are being used simple arithmetic proportions (based on rational numbers) as well as complex geometrical proportions. The simple arithmetical proportions are made of full numbers and modular constructions (repetitive) of a given dimension. This type of proportion has a static character and are obtained reports like 1:1 s 1:2 e 1:3 , until 1:8. corresponding to the tall body where we find as a model the 1:8 head’s height. This modular division of the figure determines a series of horizontal lines that represent important marks in the process of achieving the piece of clothing. The line of the basin splits the figure into two parts; the line that determines the inferior side of the knees’ articulation divides the length of the legs into two equal sides. The hand, when being tight to the body, is slightly longer than the middle of the thigh and the elbow meets the waist line. The line of the shoulders is lower than the line of the chin with 1:3 of the size of the module-unit, in this situation - head’s height. The distance between the extreme points of the shoulders includes two module-units, and the neck’s width is half of it. The width of the waist is equal with head’s height.

The researches of the fashion designers’ have established standard dimensions like the one of the sleeve %, of the coat 7/8, the minimum length of the skirt 1/3 of the clothing dimensions (2/3 being the sweater or the blouse). In the 30’s and 40’s appears the pattern ‘trois-quarts’, exterior clothing that represented % of the suit’s dimension, % being the visible part of the skirt. Simple proportion connections can be made related to the suit’s size as well as with the body’s size, in both cases obtaining rhythmic and harmonious relations between the component parts and the whole. Characteristic to these constructions is considered to be the ‘sacred Egyptian triangle’ with sides’ report of 3:4:5.

The complex proportioning relations are made of irrational numbers, deduced of geometrical constructions like Pitagora’s triangle ( rectangular triangle with angles of 30, 60 and 90 degrees), or the ‘dynamic’ rectangles with sides’ report of /2, 1/3, 1/5, 1/8 and so on (creating the sensation of continuous decrease). Are considered to be classical those types of costumes that are tailored according to the human body’s proportions. Therefore the collar’s cut will be positioned at the base of the neck, the sleeve starting from the intersection of the hand with the shoulder and ending at the wrist or at the elbow. The belt will be positioned on the waist line, the inferior part of the jacket meeting the basin line, and the overall length of the suit will meet knees’ line or the ankle’s line (for an evening dress or trousers). The proportioning of clothes is achieved by taking into consideration the vertical and the horizontal lines, the relations between surfaces, forms and lines, all coming together as a result a threedimensional perception. The conception and realization of the costumes differs from the purpose of each designer. When the aesthetic function is the main focus, the focus is on the relation between proportions, material, color, the practical purpose being a result of all of these. In the case of the uniforms and protection costumes, the construction, form and volume are generated by functionality.

Conclusions

To create a fashion article that responds to a person’s needs it is compulsory to have the detailed knowledge of the figure’s proportions as well as how these proportions have evolved in time. The author analyzes aspects of the human body construction and the relations between its’ proportions with applications in fashion.

Список литературы Body's proportions systems and applications in art and clothing

- Рачицкая Е. И., Сидоренко В. И. Моделирование и художественное оформление одежды. Ростов-на-Дону, 2002. 608 с.

- Васютинский Н. А. Золотая пропорция. М.: Молодая гвардия, 1990. 242 с.

- Meumann E. The System of aesthetics. Iassy: Agora, 1993. 154 p.