Bronze plaques from Northern Kyrgyzstan with representations of horsemen

Автор: Borisenko A.Y., Hudiakov Y.S.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145371

IDR: 145145371 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2018.46.3.100-106

Текст обзорной статьи Bronze plaques from Northern Kyrgyzstan with representations of horsemen

In the past, bronze plaques each representing a horseman, with weapons in his hands or on his belt, and sitting on a fully caparisoned horse, have been frequently found in the vast steppe expanses from the Trans-Baikal region in the east to the Southern Urals in the west, and from the Minusinsk Basin in the north to Central Asia and Tibet in the south. Currently, we have identified such plaques, originating from the Issyk-Kul Basin and from the Chuya valley, in the collections of archaeological finds owned by the museum of the Kyrgyz-Russian Slavic University, and by the private museum Raritet in Bishkek. These finds provide important evidence of the proliferation of such arts-and-crafts items during the final period of the Early Middle Ages, at the end of the 1st millennium AD, in Tian Shan and Semirechye, within the Central Asian historical and cultural region.

The earliest information about bronze plaques representing horsemen with weapons in their hands or on their belts is contained in the writings of European scientists and explorers of the 18th century. One of the first brief descriptions of such a find, recovered by tomb raiders from an ancient grave in Western Siberia, was given by J. Bell, a Scottish doctor in the Russian civil service and a member of a Russian embassy to China at the beginning of the 18th century (Zinner, 1968: 51–52). Another plaque, representing a horseman riding with a bow in his hand, from an excavated grave in the Ob-Irtysh interfluve, was purchased by scientists of the Great Northern Expedition from tomb raiders (Miller, 1999: Fig. 24, 3 ). A drawing of a plaque with a representation of a horseman (wearing a helmet and a suit of armor, with a shield on his back, and with a spear in his hands and a sword in its sheath), originating from looting excavations of the Irtysh basin mounds, was published in the article by

P.G. Demidov “regarding some Tatar antiquities”, in the English journal Archaeology in 1773 (Molodin, Hudiakov, Borisenko, 2002: Fig. 5, 3 ). One such find from southern Siberia was first described at the end of the 19th century in the catalogue of the Minusink Museum (Klements, 1886: Pl. VIII, 21). Subsequently, one bronze plaque depicting a horseman was discovered in the Trans-Baikal region (Mikhno, Petri, 1929: 323, 326; Okladnikov, 1951: 143– 144), and two were found at the Srostki cemetery, in the Upper Ob region (Gryaznov, 1930: 9; Gorbunov, 2003: Fig. 36, 1 , 2 ). Plaques with horsemen looking backwards and shooting arrows were found in one of the Kyrgyz mounds at Kopeny Chaatas, in the Minusinsk Basin (Evtyukhova, Kiselev, 1940: 50). Researchers attributed these finds to the Yenisei Kyrgyz culture (the end of the 1st millennium AD). Analyzing the images, they noted the influence of Iranian and Chinese art. According to the reconstruction proposed by scientists, these plaques were included in a multi-figure composition, adorning a pommel and reproducing a hunting scene, wherein a mounted archer was chased by a large predatory feline mammal, most probably a tiger (Evtyukhova, 1948: 52, fig. 80; Kiselev, 1949: 352, 358). One bronze plaque with representation of a horseman was found in the South Gobi Aimak in Mongolia in 1961 (Volkov, 1965: 287). Since the middle of the 1980s, the researchers of western Central Asia have published information about individual finds from this region: a schematically rendered blank of such item from Khujand in 1985 (Drevnosti…, 1985: 327), and a plaque from Chach in 1999 (Buryakov, Filanovich, 1999: 86). In 2011, information about two finds from Mongolia was published (Erdenechuulun, Erdenebaatar, 2011: 74, 419). One plaque, depicting a galloping horseman with a bow and an arrow in his hand, originating from the Issyk-Kul Basin, was examined by Kyrgyzstan researchers (Stavskaya et al., 2013: 52). In 2014, a plaque with a similar shape, found at the Sidak fortified settlement, near Turkistan City in the Turkistan Region of Kazakhstan, was described (Smagulov, 2014: 208). According to E.A. Smagulov, this find confirms that such items were manufactured in the urban craft centers of western Central Asia in the 7th–8th centuries, but they could have existed in the 9th century too. He associates representations of horsemen with the cult of the legendary hero Siyavush (Ibid.: 210–213).

In the past, the majority of such finds, except for the Kopeny ones, were accidentally found in the Minusinsk Basin, in the steppe Altai, and in the Upper Irtysh region (Borisenko, Hudiakov, 2008: 43–50). In the 1970s, a bronze plaque depicting a mounted archer was found at the Gilevo XII cemetery in mound 1, in a paired burial of an adult man with a horse and a child (Mogilnikov, 2002: 31, fig. 82, 16). Of great importance for determination of chronology, cultural attribution, and functional purpose of such plaques are similar finds from a child’s burial at the Birsk cemetery, in the Southern Urals, and a child’s burial at Kondratyevka IV, in the Upper Irtysh region (Mazhitov, Sultanova, 1994: 113; Sungatov, Yusupov, 2006: 247–252; Alekhin, 1998: 20). Judging by the finds discovered in a Kimek child’s burial, such plaques were part of headwear adornments. At the Sidak fortified settlement, in the Turkestan oasis, a flat bronze figurine of a horseman was found during excavations at a medieval citadel (Smagulov, 2014: 209).

Bronze plaques representing horsemen were repeatedly used to characterize cultural relations and to study the warfare of the Altai-Sayan nomads in the Early Middle Ages. D.G. Savinov identified such plaques among similar items of the Srostki and Kimek cultures (1976: 97). Y.A. Plotnikov compared such finds from southern Siberia and Central Asia, and pointed to the presence of similar representations in the Sogdian and East Turkestan frescoes. He made a reasonable assumption that these plaques were manufactured by Sogdian craftsmen for Turkic nomads (Plotnikov, 1982). Bronze reliefs with representations of horsemen from Kopeny Chaatas were briefly described by L.R. Kyzlasov and G.G. Korol. They noted that representations of rams along with the figures of horsemen in the Kopeny compositions have a “firm local basis” among the zoomorphic images of the art of the medieval population in the Minusinsk Basin (Kyzlasov, Korol, 1990: 83). In another study, Korol has distinguished several groups of such bronze plaques within the Eurasian steppe belt (2008: 123–136). During the target study of bronze plaques with representations of horsemen, we classified these finds according to formal features, traced the distribution area of various types of such items within the Altai-Sayan, eastern and western Central Asia, and proposed an attempt to reconstruct their function in the cultures of medieval nomadic ethnic groups (Borisenko, Hudiakov, 2008). Now, however, some more bronze pendant plaques representing horsemen, which deserve special attention, have been discovered in Kyrgyzstan.

Plaques from Northern Kyrgyzstan

Over the last few years, when studying arms collections in state historical and local history museums, folk and private museums in cities and villages of the Republic of Kyrgyzstan, with the assistance of our Kyrgyzstan colleagues, we have managed to reveal several earlier unknown bronze plaques representing armed horsemen.

Analysis of the collection of archaeological finds of the Kyrgyz-Russian Slavic University in Bishkek in 2012–2013 has revealed a rare bronze plaque depicting a mounted archer, who is shooting an arrow backwards (Hudiakov, 2014: 43–44). According to corrected information, it was found in the Issyk-Kul Basin, in

Kyrgyzstan (Stavskaya et al., 2013: 52). The plaque depicts a horseman riding at full speed (Fig. 1, 4 ). An arched stripe is shown on his head. It is rather difficult to determine whether it renders hair, or headgear partly resembling a kalpak or a bashlyk. The horseman’s face is not detailed. His left arm is stretched out, and holds the middle portion of a composite bow with convex shoulders and smoothly curved ends. His right arm, with which the horseman is probably stretching the bow, is bent at the elbow. In the middle of the bow, the arrowhead point protrudes over the wooden core. The leg of the mounted archer is shown bent at the knee and pressed to the horse’s belly, with the foot emphasized. The horseman is probably controlling the horse using his legs, having dropped the reins to free his hands. The horse is shown running from right to left. It has large ears, an elongated muzzle, and a raised neck. Forelegs with emphasized sharpened hooves are bent at the carpal joints and raised. The horse’s body is elongated in a breakneck gallop. A massive belly and a croup are shown. The hind legs and tail are absent. Probably, they did not survive and were broken off when using the plaque. The reins dropped by the horseman are shown on the head and neck of the horse, and a billet is shown on the croup. The remaining portion of the plaque is 3.3 cm high and 4 cm long (Ibid.; Hudiakov, 2014: 43–44).

Though the figurine from the Issyk-Kul Basin is depicted rather schematically, it is possible to trace a certain resemblance to similar plaques from Kyrgyz mound No. 6 at Kopeny Chaatas, in the Minusinsk Basin (Evtyukhova, Kiselev, 1940: 50, pl. VII, a, b; VIII, a; fig. 54). According to the researchers who studied these finds, a heroic hunting scene rendered in Kopeny reliefs originates from the representations of royal hunting in the art of Sasanian Iran. They also pointed to the influence of the Chinese art and similar subjects in the art of the ancient Turks in the first Turkic Khaganate epoch (Evtyukhova, 1948: 47–52; Kiselev, 1949: 352, 354– 356). Judging by the fact that the Issyk-Kul find renders the appearance of a mounted archer, who is riding and shooting backwards, rather schematically, this plaque is a local replica of a known Sasanian depiction, developed in the course of mastering this composition in Chinese art, and subsequently reworked by the Yenisei Kyrgyz. Most probably, the Karluk, Turkic-speaking nomads of Tian Shan and Semirechye during the ending period of the Early Middle Ages, as well as the nomads of the Altai-Sayan, assimilated this typical subject of heroic hunting, and represented it in their metal artworks.

In 2016, we studied three bronze plaques depicting horsemen, from the collection of the private museum Raritet in Bishkek. According to the staff of this museum, these finds originate from the Chuya valley of Kyrgyzstan. The first plaque represents a horseman riding from left to right (Fig. 1, 1 ; 2, 1 ). He is presented in profile; however, his body is turned frontally. The mounted warrior’s large head is emphasized, but the facial features are not shown. His left arm is bent at the elbow. It touches the horse’s neck. The right arm is not emphasized. His left leg is bent at the knee, and hangs down to the horse’s belly; it is probably jackbooted and, judging from certain depicted details, covered from the knee up by the hem of a robe with a wide stripe along the edge. A quiver adapter, widened towards the bottom, is depicted below the horseman’s waist. It is shown in the inclined position, most likely suspended from the belt. A semi-oval projection is depicted behind the horseman’s back, above the horse’s croup. Possibly, this is the upper end of the bow case. The head and neck of the horse are somewhat raised. A large head plume with a widened top is depicted. Slackened reins hang from the horse’s head down to the horseman’s knee. A triangular projection is shown below the horse’s head. Possibly, this depicts a tassel under the neck ( nauz ). The left foreleg of the horse is raised, and bent at the carpal joint. The lower part is broken off. The right foreleg and hind leg of the horse are shown in a standing position, with the hooves emphasized. Left hind leg is broken off. The lower part of the horse’s belly is shown unusually low, almost at the level of the stifle joint of the hind leg. Probably, the lower edge of

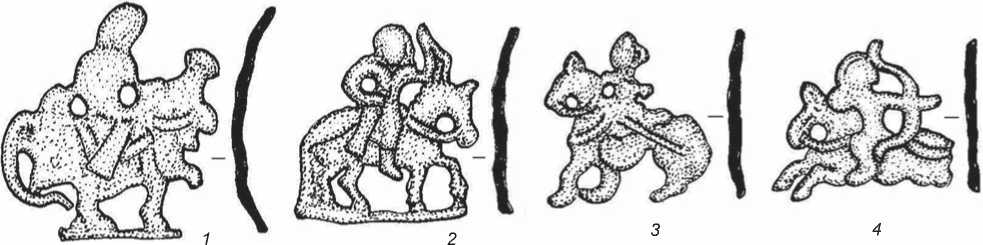

Fig. 1. Bronze plaques with representations of horsemen, from northern Kyrgyzstan.

1–3 – plaques from the Chuya valley (the Rarity museum); 4 – plaque from the Issyk-Kul Basin (the Historical Archaeological Museum of the Kyrgyz-Russian Slavic University).

Fig. 2. Plaques from the Chuya valley.

2 cm 3

the horse blanket is rendered in such a way. Also, a long thin tail, curved forward owing to damage, is depicted. Between the hooves of the horse’s forelegs and hind legs, there is a narrow horizontal stripe, typical of one of the earlier distinguished groups of ancient Turkic bronze plaques. The item is 4.8 × 4.2 cm in size. The greatest resemblance in representation of certain details can be observed between this plaque and a find from the Birsk cemetery in the Southern Urals (Borisenko, Hudiakov, 2008: 45, fig. 1, 5 ). Some similar features are observed in similar plaques, both with and without horizontal stripe, from the Minusinsk Basin and Mongolia (Ibid.: Fig. 1, 3 ; 2, 1 , 3 ; 7, 3 ).

The second plaque from the Chuya valley renders a figure of a horseman riding from left to right (Fig. 1, 2 ; 2, 2 ). He is sitting on a bridled and saddled horse, with his head and the lower part of his body turned frontally. The right arm of the horseman is bent at the elbow, his palm rests on the throat of the quiver. In his left hand, he holds a composite bow with a drawn bow-string, half of which projects above the horse’s neck. The right leg of the warrior is slightly bent at the knee, the foot hangs below the horse’s belly. Outer garments similar to a robe, with an axial slit in the front and edges below the knees, seem to be shown on the horseman. The horse is depicted with a steeply curved neck, a large head, and a sharpened ear. The chest is emphasized. The mane is rendered with triangular teeth. The left foreleg, with an emphasized hoof, is bent at the carpal, while the right one stands vertically. Hind legs are depicted with emphasized hock joints and hooves. The right leg is put together with the tail hanging down to the hoof’s base. Reins are shown on the horse’s head and neck with an arched stripe, and a line of billet is shown on the croup. All four of the horse’s legs are placed on a narrow horizontal stripe. The item is 4.0 × 3.7 cm in size. No close analogs among bronze plaques with horsemen have been revealed in southern Siberia and Central Asia.

The third plaque from the Chuya valley renders a figure of a horseman riding from right to left (Fig. 1, 3 ; 2, 3 ). He is depicted in a pointed headdress, probably a conical helmet, with a bashlyk flying behind, or unfastened hair. The facial features are not emphasized. The horseman holds the reins with his right arm bent at the elbow. The other hand is broken off. The lower part of the body and the legs are not emphasized. A long narrow strip, which probably depicts a straight sword blade, sheathed and suspended from the belt, extends from the belt towards the horse’s croup. The horse is shown with its head up, an ear sharpened at the upper part, and with a curved neck. The chest, barrel, and legs are emphasized; the hind legs are shown as together. The tail is not emphasized. Reins are shown on the horse’s head and neck, and a chest strap is depicted on the chest. A downward-hanging semi-oval on the horse’s body probably renders a saddle cloth. This item is 3.5 × 3.5 cm in size. No exact analogs have been revealed among similar finds in the Central Asian region.

Though two last plaques from the Chuya valley do not have a close resemblance to the flat bronze figurines of horsemen studied earlier, and discovered within the Central Asian region and in adjacent territories, it is possible to suggest the typological, chronological, and cultural attribution of these new finds from Kyrgyzstan on the basis of several specific details.

Typology, chronology, and cultural attribution of plaques from the Issyk-Kul Basin and the Chuya valley

The majority of researchers who studied bronze plaques depicting horsemen attributed them to the Early Middle Ages. This is supported by plaques of similar shape that were found in the Turkic and Kimek burials in the steppe Altai and the Southern Urals (Alekhin, 1998: 20; Mazhitov, Sultanova, 1994: 113). Only modern Mongolian researchers, without any extended argumentation, assigned such finds in the territory of Mongolia to the Xiongnu epoch (Erdenechuulun, Erdenebaatar, 2011: 74). It is difficult to accept their opinion because it contradicts the known cases of finding such plaques at early medieval sites. The above find from the Issyk-Kul Basin shows some resemblance to the plaques of type 2 of group 3 of bronze onlays according to the earlier developed typology of these items (Borisenko, Hudiakov, 2008: 49). As previously noted, in terms of representation it is close to the plaques from Kopeny Chaatas, each with the shape of a mounted archer, shooting an arrow backwards. These served as pommel-plaques for the saddle of a noble Yenisei Kyrgyz horseman. Researchers dated the Kopeny reliefs to the 7th–8th centuries, and noted some traits of resemblance to similar representations in the Iranian toreutics, as well as traces of Chinese influence (Evtyukhova, Kiselev, 1940: 50). However, the Issyk-Kul plaque differs from these by its rather sketchy character and by its lack of elaboration of some important details. It is reasonable to set it apart into a separate type 3 within group 3 of the plaques depicting mounted archers. Possibly, this subject (a riding horseman shooting an arrow backwards) was borrowed by the Yenisei Kyrgyz or by the Karluk from neighboring Turkic-speaking ethnic groups during the period of struggle for supremacy in Central Asia (Hudiakov, 2014: 44). It could also have been taken by craftsmen who lived in the Chuya valley immediately from Iranian and Sogdian artisans.

The first, partially damaged, plaque from the Chuya valley, which depicts a mounted rider with a belted quiver, sitting on a horse, whose legs are connected by a horizontal stripe, should be assigned to type 2 of group 1 according to the typological classification of such artifacts (Borisenko, Hudiakov, 2008: 45–46). This is supported by the general contour of the plaque, and by some representational details of the horseman and the horse. The horseman is depicted with a typical forward bend of head, and with the lower edge of the hem of his robe having a wide trimming stripe; the horse is shown with a head plume and a breast tassel. These details make this find similar to the plaque discovered earlier in a burial at the Birsk cemetery, in the Southern Urals (Mazhitov, Sultanova, 1994: 113). A head plume of similar shape is rendered on certain plaques from the Minusinsk Basin (Borisenko, Hudiakov, 2008: Fig. 2, 1 ; 3; 7, 3 ). Judging by certain traits, the plaques of type 2 of group 1 were assigned to the 6th–7th centuries, when the Tian Shan and Semirechye area was included in the First Turkic Khaganate and the Western Turkic Khaganate (Ibid.: 51). Possibly, such ornaments were also used by Turkic nomads in the times of the Turgesh Khaganate before the middle of the 8th century. Notably, the considered plaque from the Chuya valley differs rather from the Birsk find, and also from a similar one from the Ut River in Southern

Siberia, by a greater schematism and by the lack of any representation of waist-length hair (such hair being typical of the ancient Turks).

The second plaque from the Chuya valley, representing a mounted warrior with a bow in his hand and a belted quiver, who is riding on a horse with its legs and tail connected by a horizontal stripe, does not have close analogs among similar items found earlier in the Minusink Basin, Mongolia, and the Southern Urals. This find can be attributed to a separate type 3 of group 1 of plaques. At the same time, the common contour of the horseman figure can be observed both on it and on the plaques of types 1 and 2 of this group. The most important feature of this plaque is the representation of a composite bow with a drawn bow-string in left hand of a mounted archer. Judging by some resemblance in representation of the horseman to the plaques of types 1 and 2 of group 1, this find can be assigned to the period of the Western Turkic and Turgesh Khaganates, the 7th–8th centuries (Ibid.: 51).

The third plaque from the Chuya valley, which represents a horseman with a bladed weapon suspended from his belt, differs from two others primarily by the fact that the mounted warrior is shown riding from right to left. The majority of horsemen rendered on the plaques that can be attributed to the ancient Turkic art of the 6th–8th centuries are shown riding left to right. The exception are the images of lightly armed mounted archers who are shooting backwards. These are shown riding both from left to right and from right to left. Meanwhile, armored horsemen with spears in their hands and belted swords are depicted riding from right to left. These plaques pertain to the archaeological cultures of the Yenisei Kyrgyz and the Kimek of the 9th–10th centuries (Ibid.: 46–49, 51). Among the plaques representing horsemen riding from right to left, there is a distinguishable find from the Ob-Irtysh interfluve, which can be probably dated to the end of the 1st millennium AD. Judging by this analogy, the third plaque from the Chuya valley relates to the 9th–10th centuries AD. It could have belonged to one of the Karluk nomads, and could have been used till the time when the Karluk rulers adopted Islam as their state religion in the early 10th century (Istoriya…, 1984: 291).

Determining the functions of these bronze plaques from the Issyk-Kul Basin and the Chuya valley involves certain difficulties, since all of them are occasional finds. Beyond the Tian Shan area, the majority of such artifacts were occasionally found in the Altai-Sayan, Transbaikalia, Mongolia, and at a settlement in Central Asia. Only one plaque representing a Turkic horseman, rather similar in configuration, was found in a child’s burial in the Southern Urals (Mazhitov, Sultanova, 1994: 113). Two plaques, each rendering the image of an armored, mounted spearman, along with a pendant in the form of an anthropomorphic mask, were found in an undisturbed Kimek burial of a child in the Upper Irtysh region. These items were probably the ornaments of a Kimek child’s headdress (Alekhin, 1998: 20). Considering these important finds, it can be assumed that plaques that were found in the Chuya valley, representing horsemen with weapons in their hands or on their belts, were also used as suspended or sewn-on ornaments of costume worn by the Karluk—Turkic-speaking nomads. The above finds from children’s burials suggest that the ancient Turks and Kimek could have used such plaques as protective amulets forming parts of costumes or headdresses for children and teenagers. They might have been used as ornaments for the clothes of young boys, future horsemen, since they represented mounted warriors, sometimes in combination with pendants in the form of anthropomorphic masks.

Conclusions

The study of bronze plaques representing armed, mounted warriors found in the Issyk-Kul Basin and in the Chuya valley has allowed a considerable expansion of the known earlier distribution area of such items in the Central Asian historical and cultural region within Tian Shan and Semirechye, in the northern provinces of the Republic of Kyrgyzstan. As a result of analysis and ethnocultural attribution of these finds, it became evident that such items were typical in the Early Middle Ages not only of the ancient Turks, the Yenisei Kyrgyz, and the Kimek who lived in the steppe and mountain areas of Northern Kazakhstan, Western and southern Siberia, including the steppe Altai and the Minusinsk Basin, but also of western Turkic, Turgesh, and Karluk nomads in Tian Shan and Semirechye, within the northern provinces of Kyrgyzstan. As was established earlier, similar plaques were widely used as ornaments of costumes for teenagers by some Turkic-speaking nomads in a number of other areas of Central Asia (Borisenko, Hudiakov, 2008: 44–46). The occurrence of such artifacts in the Tian Shan region may be indicative of certain historical and cultural relations between the Turkic population of this area and the Yenisei Kyrgyz during the period of their confrontation with the Uyghurs and the active military expansion within Central Asia at the end of the first millennium AD, in the epoch of the greatest territorial extension of the Kyrgyz Khaganate. Furthermore, this suggests cultural contacts between the Karluk of Tian Shan and Semirechye and the Yenisei Kyrgyz and the Kimek of the Altai-Sayan and adjacent areas of Kazakhstan and Western Siberia during the final period of the Early Middle Ages.

Acknowledgements