Burial of the Pazyryk elite members at Khankarinsky dol, Northwestern Altai

Автор: Dashkovskiy P.K.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.50, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article presents the results of an interdisciplinary study of kurgan 30 at Khankarinsky Dol, located on the left bank of the Inya River, 1–1.5 km southeast of Chineta, Krasnoshchekovsky District, Altai Territory (northwestern Altai). This is a Pazyryk kurgan, under which a looted double burial of a male and an adolescent was found. Their heads were apparently oriented toward the east. Along the northern wall of the grave, an accompanying burial of seven horses was found, placed in two rows, heads oriented to the east. The morphological analysis showed all of them to be stallions, resembling those from other mounds of this group. Morphological comparison with horses from other Pazyryk kurgans in the Altai revealed both similarities and differences. Analysis of the grave goods, including iron bits, a bone pipe-shaped bead, tiny bronze daggers in wooden scabbards, a pickaxe, numerous fragments of gold foil from the horse harness, and fragments of Chinese wooden lacquer ware, suggests that the burial was made no earlier than the 4th century BC – possibly in the late 4th to early 3rd century BC. Radiocarbon analysis was carried out at the Tomsk Institute for Monitoring Climatic and Ecological Systems of the SB RAS Center for Isotopic Studies. The funerary rite and the artifacts suggest that kurgan 30 was constructed for members of the nomadic elite of the northwestern Altai.

Altai, Scythian-Saka period, Pazyryk culture, funerary rite, grave goods, radiocarbon dating

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146788

IDR: 145146788 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2022.50.2.071-080

Текст научной статьи Burial of the Pazyryk elite members at Khankarinsky dol, Northwestern Altai

The Khankarinsky Dol cemetery is a part of the Chineta archaeological microdistrict located in the vicinity of the village of Chineta, in Krasnoshchekovsky District, Altai Territory (northwestern Altai). The site is in the eastern part of the second floodplain terrace on the left bank of the Inya River (left tributary of the Charysh River), 1–1.5 km southeast of that village (Fig. 1). For over twenty years, archaeological research at this cemetery has been carried out by the Krasnoshchekovo Archaeological Expedition of the Altai State University. Currently, more than thirty objects dated to the Scythian-Saka period have been excavated. The present article introduces the preliminary results from studying kurgan 30 at Khankarinsky Dol, which belongs to the Pazyryk culture of the Altai.

Description of the funerary rite

Kurgan 30 was found in the southern part of the Khankarinsky Dol cemetery. The diameter of the stone mound, composed of two to four layers of small and medium-sized stones, reached 9.75 m along the N-S line, and 11 m along the W-E line (Fig. 2). The height of the stone structure was 0.5 m, and reached 0.7 m together with the layer of soil. A hollow reaching 4 m in diameter was in the central part of the mound. A subrectangular grave-pit measuring 3.3 × 3.2 × 3.04 m (the depth of

Fig. 1 . Location of the Khankarinsky Dol cemetery.

next to them. Fragments of pelvis, tibia, and vertebrae remaining from the male skeleton were discovered to the east of the skull. Ritual food (sheep bones) and an iron ringed knife were near them. Three clusters of gold foil fragments were among the bone fragments. A wooden chopping-block 1.45 m long, probably remaining from a burial structure in the form of a frame, has been preserved along the southern wall of the grave.

An accompanying burial of seven horses, which were laid in two rows one after another and oriented with their heads to the east, was along the northern wall of the gravepit, at a depth of 2.72–3.01 m (Fig. 3). Iron ringed bits were found in the teeth of five of them. Two bits were wrapped in gold foil. A fragment of a round bone flat bead was discovered near the ribs of one horse. In addition, numerous fragments of foil, which might have remained from harness-decoration, were in the area of the ribs and three skulls of horses.

Cultural and chronological attribution of the grave goods the grave is given from the zero reference point) was found under the mound. It contained a paired burial of people, badly damaged by robbers. Although the bones of the skeletons turned out to be severely damaged and scattered over the grave, it was possible to establish the sexes and ages of the buried persons: a male 23– 25 years of age, and adolescent male 13–14 years of age*. The crushed skull of an adult was discovered in the central part of the grave-pit, at a depth of 3 m. Two bronze daggers and wooden scabbard lay 0.35 m to the west of it, and a bronze pickaxe with a wooden socket was found 0.3 m to the south. Two accumulations of lacquer fragments on the wooden base, possibly from lacquer items (cups?), were discovered near the skull, on the northern and southern sides. The jaw of a teenager was in the northeastern corner of the grave, near the skull of horse No. 5. The dead persons were oriented with their heads to the east. The remains of tibia bones, probably from the skeleton of the teenager, and ribs were located 1.1 m northwest of the man’s skull. Two more bronze daggers and fragments of a poorly preserved wooden scabbard were

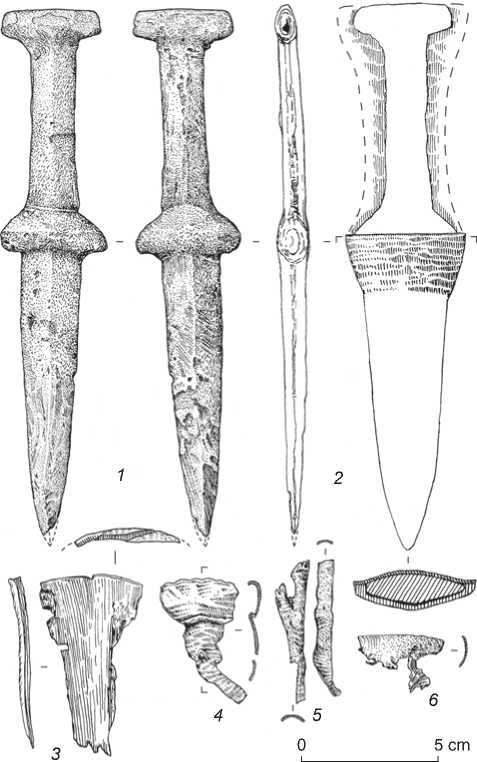

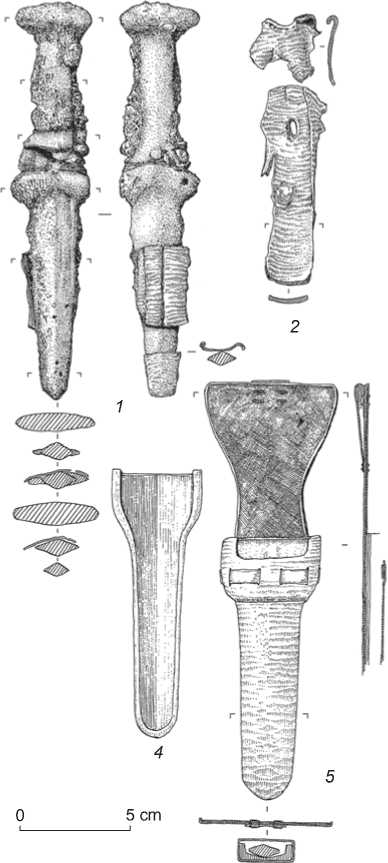

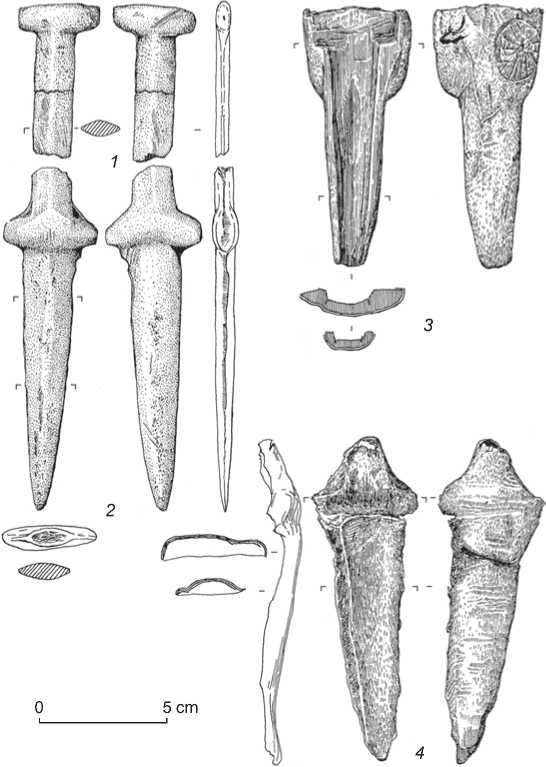

Despite the robbery of the kurgan, grave goods included various types of items. Weaponry was represented by four bronze daggers in wooden scabbards, and a bronze pickaxe. All daggers were replicas of real items reduced in size, and each had a pommel in the form of a bar, and a straight crossbar. The total length of the first dagger (Fig. 4, 1 ), which is the best preserved, is 19.3 cm; the length of the rhombic blade is 10.6 cm; width at the crossbar 2.1 cm; thickness 0.9 cm. The blade-tip of the second dagger had been broken off (Fig. 5, 3 ). The length of the surviving part of the blade is ca 8 cm; length of the handle 6.2 cm. The crossbar is somewhat

Fig. 2 . Kurgan 30 after removing the mound.

Fig. 3 . Burial in kurgan 30.

arcuate, but is closer to straight line. The third dagger (Fig. 5, 1 ) was heavily oxidized. Its maximum width in the area of the crossbar is 2.3 cm; thickness is about 1 cm. The total length of the surviving part of that item is 18 cm; length of the blade 9.5 cm; length of the handle 6.6 cm. The fourth dagger (Fig. 6, 1 , 2 ) was broken in three places. The original total length was probably 19.5 cm; length of the blade 10.1 cm. The width of the blade in the area of the crossbar is 2.0 cm; length of the handle 1.5 cm, maximum thickness at the crossbar 0.8 cm.

Items of this type are well known from the Pazyryk sites in the Altai (Kiryushin, Stepanova, 2004: 54– 55; Kubarev, 1991: 73–75; Kubarev, Shulga, 2007: 74–81). For example, bronze and wooden miniature replicas of daggers with pommels in the form of a bar and straight crossbars have been found in burials at the cemeteries of Aragol (kurgan 1), Barburgazy II (kurgan 18) (Surazakov, 1989: 41–42, fig. 16, 4 , 6), Kaindu (kurgan 13) (Kiryushin, Stepanova, 2004: 55, fig. 18, 2 ), Yustyd II (kurgan 23) (Kubarev, 1991: Pl. LII, 23), and others. A bronze dagger from kurgan 3 at Kyzyl-Dzhar V may be attributed to the same type. Although its crossbar retained a slight “brokenness” of shape, it tended towards the straight line (Mogilnikov, 1983: 40–47; Surazakov, 1989: 42, fig. 16, 3 ). In some cases, these specimens had slotted handles. This

Fig. 5 . Bronze daggers ( 1 , 3 ), fragment of wooden scabbard ( 2 ), and their reconstruction ( 4 , 5 ).

distinguishes them from the daggers found in kurgan 30 at Khankarinsky Dol. Daggers (and their reduced replicas) with straight crossbars are traditionally considered to be later, existing from the 4th century BC and becoming widespread in the 3rd–2nd centuries BC (Surazakov, 1989: 49). Daggers of the type under consideration, but made of iron, occur among the evidence of the Kamen culture; for example, in burial 2 of kurgan 16 at the Novotroitsk II cemetery, dated to the late 4th–3rd centuries BC (Mogilnikov, 1997: 46, fig. 37, 4). Bronze daggers with straight crossbars but mushroom-shaped pommels have been found in the contemporaneous Sagly sites of Tuva, such as in kurgan 5 at the Sagly-Bazhi II cemetery (Grach, 1980: 169, fig. 31). However, it may be the case that bronze daggers with straight crossbars could have existed at the initial stage of the Pazyryk culture of the Altai (Kubarev, Shulga, 2007: 82). A dagger of the 6th century BC from grave 38 at the Staroaleika-2 cemetery, in the Upper Ob region, had an almost straight crossbar (Kiryushin, Kungurov, 1996: Fig. 9, 2).

Fragments of three scabbards were also found in kurgan 30 at Khankarinsky Dol. The best-preserved scabbard was from the fourth dagger (Fig. 6, 3 , 4 ). The lower part of the scabbard was made of wood; the upper part, of leather. Special grooves were cut inside the wooden base, according to the shape of the dagger. The length of its surviving part is 10.5 cm; width at the bottom 1.4 cm; width at the top

4.2 cm. Notably, the upper part of the wooden base retains the rectangular shape of dagger’s crossbar, which it originally had. The length of the preserved leather part of the scabbard is 12.6 cm. It repeated the shape of the wooden part. Similar scabbards, consisting of two parts, might have been made for the rest of the daggers. At least this was possible to observe for the first and third dagger, despite the poor preservation of the scabbards (see Fig. 4, 2–6 ; 5, 2 , 4 , 5 ). This allowed us to perform their reconstruction (see Fig. 5, 4 , 5 ).

Scholars believe that real scabbards for daggers consisted of two planks, while those with wooden bases and leather tops were specially made for funerary rites (Kubarev, 1981: 48; Kubarev, Shulga, 2007: 84–85). At the same time, scabbards consisting of one wooden plank and a leather part are known both from the early and late stages of the Pazyryk culture (Rudenko, 1953: 240, fig. 149; Sorokin, 1974: 90; Kubarev, 1981: 44–45). This type of item, used by the Altai nomads of the Pazyryk time, evolved from a single prototype—the Saka scabbards of the 6th–5th centuries BC. Scabbards similar to Saka scabbards were quite widespread among the Sauromatians,

Scythians, and many Iranian peoples.

It is no coincidence that V.D. Kubarev even suggested the term “scabbard of the Iranian-Altai type”. He emphasized that many nomadic peoples wore them in the same manner. For example, as has been repeatedly established, nomads usually wore their dagger in the scabbard on their hip, and fastened it to their legs with special straps so that it would not dangle (Kubarev, 1981: 51–52; Kubarev, Shulga, 2007: 103–105). Obviously, similar fastening elements must have been present on the scabbards from kurgan 30 at Khankarinsky Dol.

The bronze pickaxe was 14 cm long (Fig. 7, 1 ); the maximum width of the striking part was 1.2 cm; the maximum width of the back 1.6 cm; the outer diameter of the socket 1 cm, and the inner diameter 0.8 cm. The item under discussion survived, together with a fragment of leather strap and a wooden socket 5.6 cm long, which made it possible to reconstruct the item (Fig. 7, 2–6 , 8 ). Different approaches to the classification of pickaxes have been proposed (Kocheev, 1988; Surazakov,

1989: 51–54; Hudiakov, 1995; Kubarev, 1991: 77–76; Kiryushin, Stepanova, 2004: 58–59). Depending on the size, they were divided into real, reduced, and miniature items. V.A. Kocheev mentioned (1988: 147) that the length of real bronze shaft-hole pickaxes was 18–20 cm, and the length of iron pickaxes was over 20 cm. Accordingly, he considered the group of pickaxes with this parameter less than 18 cm as reduced items. A.S. Surazakov pointed out that pickaxes with the striking part less than 20 cm long could also be considered as reduced (1989: 51). A more differentiated approach was suggested by Kubarev. He identified three groups: full-sized iron battle pickaxes with a total length of 20–24 cm, reduced pickaxes made of bronze (total length of 12–15 cm), and miniature bronze and wooden pickaxes (total length of 9–10 cm). Contrary to the opinion of many other scholars, Kubarev emphasized that reduced bronze replicas most likely were not used on the battlefield. In support of his view, he mentioned the analysis of the items and traces from the blows of real combat pickaxes on the skulls of killed people and horses (Kubarev, 1991: 79).

5 cm

Fig. 7 . Grave goods.

1 – bronze pickaxe; 2–6 – leather fragments from fastening; 7 – iron knife; 8 – reconstruction of the pickaxe with leather fastening to the belt.

5 cm

The item from kurgan 30 at Khankarinsky Dol belongs to shaft-hole pickaxes with rounded back and striking parts (Surazakov, 1989: 52; Kiryushin, Stepanova, 2004: 58). This was one of the most common types of weaponry among the nomads in the Altai Mountains in the Pazyryk period (Kubarev, Shulga, 2007: 86–87; Surazakov, 1989: 53–54). Such pickaxes have been found at the cemeteries of Tytkesken VI (kurgans 6, 11, 29), Biyke III (kurgan 2), Kaindu (kurgan 12) and others (Kiryushin, Stepanova, 2004: 58, fig. 20, 4 ; 21, 1 , 2 , 4 ; 22, 6 ). Moreover, such pickaxes, as well as items with the very short, barely noticeable socket, are known from Tuva (Grach, 1980: 170, fig. 32, 4–6 ; 53) and northwestern Mongolia (Tsevendorj, 1978: Fig. 2, 5 ). There are almost no pickaxes of this type in the Upper Ob region and Kazakhstan, with the exception of two items (Mogilnikov, 1997: 48–52; Kiryushin, Stepanova, 2004: 60–61).

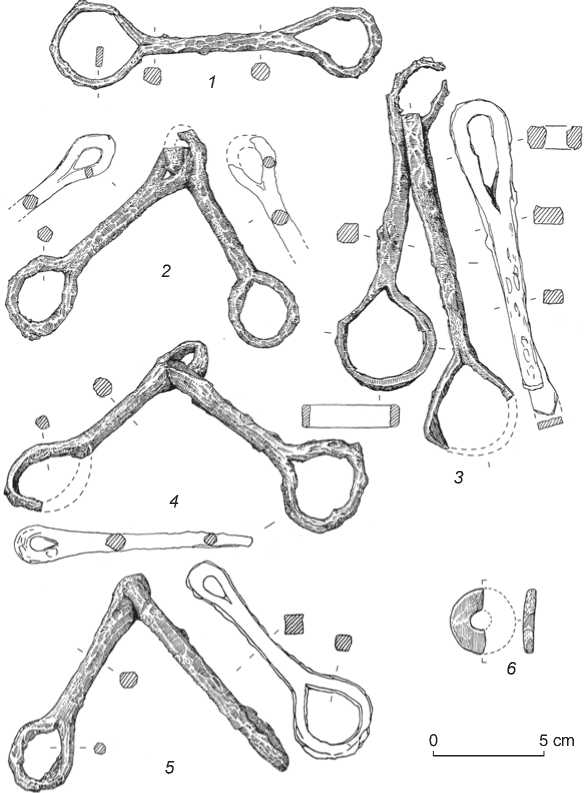

In addition to weapons, elements of horse harness, including a round bone flat bead (Fig. 8, 6 ) and five ringed iron bits (Fig. 8, 1–5 ), were discovered in kurgan 30 at Khankarinsky Dol. The bead, of which only a half has survived (Fig. 8, 6 ), originally had a diameter of

3 cm, a thickness of 0.5 cm, and a round hole 0.9 cm in diameter. One of its sides was slightly convex. This item is interpreted as simple flattened saddle bead used as a locking button-plaque. The role of the loop was played by the knot at the end of the strap passed into it. In kurgans of the Early Pazyryk period and times close to this, such beads were usually found one at a time (Shulga, 2015a: 156). They could have also been used for tightening the front saddlebows (supports) together with small pendants (Stepanova, 2006: 133). Beads of that type have been found in burials at Chendek-6a (kurgan 5) (Kireev, Shulga, 2006), Kaindu (kurgan 7) (Kiryushin, Stepanova, 2004: 53–56, Fig. 55, 8 ), Kok-Su I (kurgan 31) (Sorokin, 1974), Borotal-1 (kurgan 99), Borotal-3 (kurgans 2, 4), Ala-Gail-3 (kurgan 11) (Kubarev, Shulga, 2007: 224, Fig. 30, 12–16 ; 234, fig. 39, 12–16 ; 238, fig. 43, 6 , 10 ), Kool I (kurgan 501) (Bogdanov, Slyusarenko, 2003), Chineta II (kurgan 21) (Dashkovskiy, 2018), etc.

Two-piece iron bits with the single-ringed end of the links are represented by four sets (Fig. 8, 2–5 ) and one link (Fig. 8, 1 ). In all cases, the end of the link look rather like a loop than a ring. The links in two sets of bits were 15.0–15.7 cm long; the rest were 10.7– 11.3 cm long; the diameter of the outer ring-loop was 4 cm and 2.5–4.5 cm. Bits of that type have been found in large numbers both at the cemeteries of Khankarinsky Dol and Chineta II, and at other Pazyryk sites in the Altai (Dashkovskiy, Meikshan, 2015; Kubarev, 1991: 42–44; Kubarev, Shulga, 2007: 270, fig. 4, 11–18 ; Shulga, 2015a: 93–97; Kiryushin, Stepanova, 2004: 45–46; and others). They appeared in the Altai Mountains in the 6th century BC and existed throughout the entire period of the Pazyryk culture. Some scholars have mentioned the predominance of bits with sub-quadrangular cross-section of the rod and loop-shaped end of the link in the Late Pazyryk culture, and round cross-section of the rod and ring-shaped outer end in the Early Pazyryk culture (Surazakov, 1989: 25; Kubarev, 1992: 32). However, more detailed analysis has revealed that both varieties occurred both in early and late burials of the Pazyryk culture (Shulga, 2015a: 96). Four bits out of those found in kurgan 30 at Khankarinsky Dol had sub-quadrangular cross-sections of the rod, and one item probably had a round crosssection. Two bits discovered between the

Fig. 8 . Iron bit ( 1–5 ) and bone tubular bead ( 6 ).

skulls of the first and second, as well as the fourth and sixth horses, were wrapped in golden foil. The foil’s fragments, probably remaining from harness decoration, were found near the skulls (or under them) of the second, fourth, and fifth horses. Accumulations of foil were located in the area of the hind hooves of the sixth horse, and in the central and eastern parts of the grave.

Valuable finds—two clusters of lacquer fragments (red and black) on the wooden base (they will be analyzed in a separate study)—were discovered near the skull of the man. At this stage, it can be assumed that these were the remains of wooden lacquerware, possibly er-bei wine cups (?). Previously, similar items of Chinese import were found in kurgans 21 and 31 at Chineta II, located in the same river valley as the Khankarinsky Dol necropolis (Dashkovskiy, Novikova, 2017). These kurgans date back to the second half of the 4th–3rd centuries BC. Chinese items have been discovered in the elite Pazyryk kurgans also dated mainly to the 4th–3rd centuries BC (Shulga, 2015b: 370).

Radiocarbon dating

The dating of kurgan 30 at Khankarinsky Dol on the basis of grave goods was supplemented by radiocarbon analysis, which was carried out at the Analytical Center for Isotope Research at the Institute of Monitoring of Climatic and Ecological Systems SB RAS in Tomsk. The 14C date of 2562 ± 150 BP was obtained from a horse bone sample. Its calibration was performed using the CALIB REV-8.2 software by G.V. Simonova, and gave the following values: 768–416 BC by 1δ (68 %), 910– 198 BC by 2δ (95 %), and the average date of 585 BC.

The results point to a somewhat early date, but generally within the period of the Pazyryk culture in the Altai. They complement the information on kurgans at Khankarinsky Dol and Chineta II in the Chineta archaeological microdistrict (Dashkovskiy, 2018, 2020; and others) obtained by radiocarbon dating. In the future, it is planned to re-analyze the samples in another laboratory, also using the AMS-method, which will make it possible to clarify the age of the site. As a result of studying the archaeological evidence, it has been established quite accurately that this burial did not contain any items that would indicate its exceptionally early date within the Pazyryk period. However, a kurgan belonging to the early stage of that culture with a typical set of grave goods was previously excavated at Khankarinsky Dol, which indicates the penetration of the “Pazyryks” into this area at the turn of the 6th– 5th centuries BC (Dashkovskiy, 2020). Distinctive features of the goods discovered in the burial under discussion, including the presence of Chinese imported items, makes it possible to conclude that kurgan 30 was made no earlier than the 4th century BC, possibly in the second half of the 4th to early 3rd century BC.

Morphological description of the horses

Studying horse remains from kurgans of the Pazyryk culture in the northwestern Altai is an important field of research. Some of its results have been published (Plasteeva, Dashkovskiy, Tishkin, 2020). Therefore, we shall present only the most important morphological parameters of seven horses from kurgan 30 at Khankarinsky Dol and findings*. It has been established that all the individual horses were stallions. Three horses were 15–18 years of age; the rest were of different ages, namely, 3–4, 4–5, 5–6, and 9–12 years. According to the height at the withers, they corresponded to two categories: medium height (136–144 cm) and height below average (128–136 cm). According to the massiveness of their bones, the horses were distinguished as medium-legged and semi-thin-legged. In terms of the height at the withers, they resembled the horses from other Pazyryk cemeteries in the Altai. There were no horses above average height in any excavated kurgans at the site. This might have been caused by local features of horse keeping and use, or adapting to the natural and climatic conditions of the region. Another possible factor is that most of the kurgans at the Khankarinsky Dol site date back to the final stage of the Pazyryk culture (4th–3rd centuries BC), when horses could have been smaller. In terms of bone massiveness, these animals also did not differ much from Pazyryk horses from other regions of the Altai. Noteworthy is the predominance of medium-legged horses in kurgan 30, since semi-thin-legged horses were more typical of the burials at the Pazyryk cemeteries (Grebnev, Vasiliev, 1994; Kosintsev, Samashev, 2014: 136–141; Plasteeva, Tishkin, Sablin, 2018).

According to the dimensional features of skeletal bones, the horses from kurgan 30 did not differ from horses found in other burials of Khankarinsky Dol, which indicates the morphological homogeneity of horses from the northwestern Altai. Generally, horses from kurgans at that site were somewhat larger in skull size than those buried at the well-known cemeteries of Ak-Alakha-1 and Ulandryk I–II, and in their length they were smaller only than horses from Berel, Pazyryk, and Shibe. According to the main features of humerus, radius, femur, and tibia, as well as length of metacarpal and metatarsal bones, they were somewhat smaller than horses from the latter three cemeteries. They were comparable to horses from Ak-Alakha-1 and Kuturguntas I, but larger than horses from Ulandryk I and II. These preliminary comparisons additionally indicate the decrease in sizes of horses at the late stage of the Pazyryk culture (Plasteeva, Dashkovskiy, Tishkin, 2020: 124–128).

Social attribution of burials

The area of the Pazyryk sites suggests the presence of an extensive political entity of nomads, which had both a center headed by political elite, and a periphery with its own power system (Tishkin, Dashkovskiy, 2019). “Royal” burials remaining from the representatives of the supreme power are quite easily identified from their scale and the richness of the grave goods. However, identification of burial sites of the regional elite is hampered by the absence of similar clear markers. At the present stage, problems associated with the study of the elite in the structure of nomadic societies, including the Scythian-Saka period, are well investigated in the Nomadic Studies (Elita…, 2015: 11–98). The indicators of the regional elite, along with the parameters of the burial complexes, should include “prestigious” items that had the greatest value in the nomadic society (Kharinsky, 2004: 108). In addition to determining the dynamics of changes in the social system, an important function of the elite was the formation of a certain “nomadic fashion” (Dashkovskiy, 2005: 241). This was manifested by the desire of the local authorities to imitate political leaders in possessing the most “high-status” items. For the Pazyryk culture, these included imported goods, such as lacquerware, weaponry, elements of clothing complex made with gold, and jewelry in the Scythian animal style (Elita…, 2015: 11–98).

“Royal” and elite sites of the Pazyryk culture are located mainly in the central and southeastern Altai, delineating the sacred center of the political entity of the “Pazyryk people” (Kiryushin, Stepanova, Tishkin, 2003: 8–14, fig. 3). However, the geographical spread of this entity was much larger, and included vast areas in the foothills and mountains of the Russian Altai, as well as adjacent areas of Mongolia, Kazakhstan, and China. The geographical locations of the sites and results of their research have made it possible to identify several political zones where the population was concentrated, as well as “royal” and elite burial complexes (Anufriev, 1997; Tishkin, Dashkovskiy, 2019). N.V. Polosmak pointed out the presence of elite burials that differed from “royal” burials in an individual region, in particular in the southeastern Altai. In the social context, she used the terms “middle layer”, “clan aristocracy”, or “elite layer” as synonyms (Polosmak, 1994: 56; 2001: 280). The northwestern Altai was one of the areas of the Pazyryk culture, which included the so-called Charysh (northwestern) group of sites in the Charysh River basin, with a complex in the valley of the Sentelek River and the cemeteries of Khankarinsky Dol and Chineta II. So far, only one Pazyryk “royal” kurgan has been reliably identified there at the Urochishche Balchikova-3 cemetery (kurgan 1), in the Sentelek River valley (Shulga, Demin, 2021: 43–63). It was previously mentioned that it is possible to identify the burials belonging to the representatives of the regional elite at the Khankarinsky Dol and Chineta II sites (Elita…, 2015: 99–107). Analysis of the evidence confirmed the attribution of the kurgan under discussion to such burials, taking into account several important points. According to its parameters, kurgan 30 at Khankarinsky Dol belongs to the group of small barrows, since its maximum diameter is 11 m; its height reaches 0.7 m, and the volume of the gravepit is about 28 m3. However, the paired burial of a male adult and a teenager was accompanied by the burial of seven horses, which is the most important sign of the relatively high social status of the buried persons. Approximately 37 % of the Pazyryk burials contained an accompanying burial of one to three horses. Burials with more than three horses (from 4 to 22) were found only in a little more than twenty excavated kurgans (Tishkin, Dashkovskiy, 2003: 147–149). However, all of them were distinguished by the relatively large sizes of both the mound and the intra-burial structure. Importantly, kurgan 30 at Khankarinsky Dol yielded Chinese wooden lacquerware, which is interpreted as a sign of a rather high social status of the buried persons of the Pazyryk culture (Dashkovskiy, Novikova, 2017). Weapons (four miniature daggers in wooden scabbards, and a pickaxe), as well as a significant amount of golden foil, including the foil remaining from decorating the elements of horse equipment, were found in the burial, despite its robbery. By the character of its grave goods and the presence of the accompanying burial of seven horses, kurgan 30 at Khankarinsky Dol stands out noticeably among other excavated kurgans both in the Chineta archaeological microdistrict and in the entire northwestern Altai. This makes it possible to draw a conclusion about the relatively high social status of the buried persons.

Conclusions

The study has shown that kurgan 30 at Khankarinsky Dol belonged to the Pazyryk culture of the Altai. The analysis of the archaeological evidence, and radiocarbon dating, have shown that the time of this paired burial was not earlier than the 4th century BC—possibly the second half of the 4th to early 3rd century BC. The presence of the accompanying burial of seven horses, imported Chinese items, four miniature daggers in wooden scabbards, and the rich decoration of horse equipment, indicates high social status for the buried persons and their affiliation with the regional elite.

Morphological analysis of the horse remains from kurgan 30 has shown that all animals were stallions; they did not differ from horses buried in other burials at Khankarinsky Dol. Comparison with horses from other Pazyryk kurgans, studied in different regions of the Altai, has revealed both morphological similarities and differences.

Список литературы Burial of the Pazyryk elite members at Khankarinsky dol, Northwestern Altai

- Anufriev D.E. 1997 Sotsialnoye ustroistvo pazyrykskogo obshchestva Gornogo Altaya. In Sotsialno-ekonomicheskiye struktury drevnikh obshchestv Zapadnoy Sibiri: Materialy Vseros. nauch. konf. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 108-111.

- Bogdanov E.S., Slyusarenko I.Y. 2003 Arkheologicheskiye issledovaniya na pamyatnike Kool- 1 v doline r. Aktru (Gornyi Altai). In Problemy arkheologii, etnografii, antropologii Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. IX (I). Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 272-276.

- Dashkovskiy P.K. 2005 Formirovaniye elity kochevnikov Gornogo Altaya v skifskuyu epokhu. In Sotsiogenez v Severnoy Azii: Materialy Vseros. nauch. konf. s mezhdunar. uchastiyem. Irkutsk: Irkut. Gos. Tekhn. Univ., pp. 239-244.

- Dashkovskiy P.K. 2018 Radiouglerodnoye i arkheologicheskoye datirovaniye pogrebeniya skifskogo vremeni na mogilnike Chineta II (Altai). Narody i religii Yevrazii, No. 2: 9-23.

- Dashkovskiy P.K. 2020 An Early Pazyryk kurgan at Khankarinsky Dol, Northwestern Altai: Chronology and attribution of artifacts. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, vol. 48 (1): 91-100.

- Dashkovskiy P.K., Meikshan I.A. 2015 Izucheniye regionalnoy elity kochevnikov Yuzhnoy Sibiri, Zapadnogo Zabaikalya i Severnoy Mongolii epokhi pozdney drevnosti (na primere pazyrykskogo obshchestva i khunnu). In Elita v istorii drevnikh narodov Yevrazii, P.K. Dashkovskiy (ed.). Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 99-107.

- Dashkovskiy P.K., Novikova O.G. 2017 Chinese lacquerware from the Pazyryk burial ground Chineta II, Altai. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, vol. 45 (4): 102-112.

- Elita v istorii drevnikh i srednevekovykh narodov Yevrazii. 2015 P.K. Dashkovskiy (ed.). Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ.

- Grach A.D. 1980 Drevniye kochevniki v tsentre Azii. Moscow: Nauka.

- Grebnev I.E., Vasiliev S.K. 1994 Loshadi iz pamyatnikov pazyrykskoy kultury Yuzhnogo Altaya. In Polosmak N.V. “Steregushchiye zoloto grify” (akalakhinskiye kurgany). Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 106-111.

- Hudiakov Y.S. 1995 Kollektsiya oruzhiya skifskogo vremeni iz mogilnikov Saldam i Ust-Edigan. In Izvestiya laboratorii arkheologii, No. 1. Gorno-Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 87-101.

- Kharinsky A.V. 2004 Prestizhniye veshchi v pogrebeniyakh Baikalskogo poberezhya kontsa I tys. do n.e. - nachala II tys. n.e. kak pokazatel regionalnykh kulturno-politicheskikh protsessov. In Kompleksniye issledovaniya drevnikh i traditsionnykh obshchestv Yevrazii. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 108-114.

- Kireev S.M., Shulga P.I. 2006 Sbruyniye nabory iz Uimonskoy doliny. In Izucheniye istoriko-kulturnogo naslediya narodov Yuzhnoy Sibiri, iss. 3/4. Gorno-Altaisk: pp. 90-107.

- Kiryushin Y.F., Kungurov A.L. 1996 Mogilnik rannego zheleznogo veka Staroaleika-2. In Pogrebalniy obryad drevnikh plemen Altaya. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 115-134.

- Kiryushin Y.F., Stepanova N.F. 2004 Skifskaya epokha Gornogo Altaya. Pt. III: Pogrebalniye kompleksy skifskogo vremeni Sredney Katuni. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ.

- Kiryushin Y.F., Stepanova N.F., Tishkin A.A. 2003 Skifskaya epokha Gornogo Altaya. Pt. II: Pogrebalnopominalniye kompleksy pazyrykskoy kultury. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ.

- Kocheev V.A. 1988 Chekany Gornogo Altaya. In Problemy izucheniya kultury naseleniya Gornogo Altaya. Gorno-Altaisk: GANIIIYaL, pp. 144-162.

- Kosintsev P.A., Samashev Z.S. 2014 Berelskiye loshadi: Morfologicheskoye issledovaniye. Astana: Filial Inst. arkheologii im. A.K. Margulana. (Materialy i issledovaniya po arkheologii Kazakhstana; vol. V).

- Kubarev V.D. 1981 Kinzhaly iz Gornogo Altaya. In Voyennoye delo drevnikh plemen Sibiri i Tsentralnoy Azii. Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 29-54.

- Kubarev V.D. 1991 Kurgany Yustyda. Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Kubarev V.D. 1992 Kurgany Sailyugema. Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Kubarev V.D., Shulga P.I. 2007 Pazyrykskaya kultura (kurgany Chui i Ursula). Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ.

- Mogilnikov V.A. 1983 Kurgany Kyzyl-Dzhar II-V i nekotoriye voprosy sostava naseleniya Altaya vo vtoroy polovine I tys. do n.e. In Voprosy arkheologii i etnografii Gornogo Altaya. Gorno-Altaisk: GANIIIYaL, pp. 40-71.

- Mogilnikov V.A. 1997 Naseleniye Verkhnego Priobya v seredine - vtoroy polovine I tys. do n.e. Moscow: Nauka.

- Plasteeva N.A., Dashkovskiy P.K., Tishkin A.A. 2020 Morfologicheskaya kharakteristika loshadey iz pamyatnikov pazyrykskoy kultury Severo-Zapadnogo Altaya. Teoriya i praktika arkheologicheskikh issledovaniy, No. 4: 123-130.

- Plasteeva N.A., Tishkin A.A., Sablin M.V. 2018 Loshadi iz Bolshogo Katandinskogo kurgana (Altai). In Sovremenniye resheniya aktualnykh problem yevraziyskoy arkheologii, iss. 2. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 107-109.

- Polosmak N.V. 1994 “Steregushchiye zoloto grify” (ak-alakhinskiye kurgany). Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Polosmak N.V. 2001 Vsadniki Ukoka. Novosibirsk: INFOLIO.

- Rudenko S.I. 1953 Kultura naseleniya Gornogo Altaya v skifskoye vremya. Moscow, Leningrad: Nauka.

- Shulga P.I. 2015a Snaryazheniye verkhovoy loshadi v Gornom Altaye i Verkhnem Priobye, Pt. II: (VI-III vv. do n.e.). Novosibirsk: Izd. Novosib. Gos. Univ.

- Shulga P.I. 2015b Datirovka kurganov Pazyryka i kitaiskikh zerkal s T-obraznymi znakami. In Arkheologiya Zapadnoy Sibiri i Altaya: Opyt mezhdistsiplinarnykh issledovaniy. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 366-371.

- Shulga P.I., Demin M.A. 2021 Kurgany Senteleka. Novosibirsk: Izd. SO RAN.

- Sorokin S.S. 1974 Tsepochka kurganov vremen rannikh kochevnikov na pravom beregu r. Kok-Su (Yuzhniy Altai). ASGE, iss. 16: 62-91.

- Stepanova E.V. 2006 Evolyutsiya konskogo snaryazheniya i otnositelnaya khronologiya pazyrykskoy kultury. Arkheolologicheskiye vesti, iss. 13: 102-150.

- Surazakov A.S. 1989 Gornyi Altai i yego severniye predgorya v epokhu rannego zheleza: Problemy khronologii i kulturnogo razgranicheniya. Gorno-Altaisk: GANIIIYaL.

- Tishkin A.A., Dashkovskiy P.K. 2003 Sotsialnaya struktura i sistema mirovozzreniy naseleniya Altaya skifskoy epokhi. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ.

- Tishkin A.A., Dashkovskiy P.K. 2019 The social complexity of the Pazyryk culture in Altai, 550-200 BC. Social Evolution and History, vol. 18 (2): 73-91.

- Tsevendorj D. 1978 Chandmanskaya kultura. In Arkheologiya i etnografiya Mongolii. Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 108-117.