CervixCan-Net: An Enhanced Cervical Cancer Classification Approach using Deep Learning

Автор: Anik Kumar Saha, Jubayer Ahamed, Dip Nandi, Niloy Eric Costa

Журнал: International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications @ijisa

Статья в выпуске: 6 vol.17, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

One of the biggest causes of cancer-related fatalities among women is still Cervical cancer, especially in low and middle-income nations where access to broad screening and early detection may be limited. Cervical cancer is curable if detected in its early stages, but asymptomatic progression frequently results in late diagnosis, which makes treatment more difficult and lowers survival chances. Even though they work well, current screening methods including liquid-based cytology and Pap smears have drawbacks in terms of consistency, sensitivity, and specificity. Recent developments in Deep Learning and Artificial Intelligence have shown promise for greatly improving Cervical cancer detection and diagnosis. In this work, we have introduced CervixCan-Net, a novel Deep Learning based model created for the precise classification of Cervical cancer from histopathology images. Our approach offers a solid and dependable classification solution by addressing common problems like overfitting and computational inefficiency. CervixCan-Net performs better than many state-of-the-art models according to a comparison investigation. CervixCan-Net, with an impressive test accuracy of 99.83%, provides a scalable, automated Cervical cancer classification solution that has great promise for improving patient outcomes and diagnostic accuracy.

Cervical Cancer, Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), Deep Learning (DL), Classification

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/15020107

IDR: 15020107 | DOI: 10.5815/ijisa.2025.06.10

Текст научной статьи CervixCan-Net: An Enhanced Cervical Cancer Classification Approach using Deep Learning

Cervical cancer remains a significant global health challenge that affects women mostly in low- and middle income nations where early identification and widespread screening may not be sufficiently supported by the healthcare system. If caught early, this kind of cancer—which starts in the cells lining the cervix—is very curable. However, because early-stage cervical cancer is asymptomatic, it frequently remains undiagnosed until it has evolved to more advanced stages, at which point treatment choices are less effective and the prognosis is worse. With an anticipated 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths from cervical cancer in 2020 alone [1], cervical cancer ranks among the world’s major causes of cancer-related deaths among women (WHO) [2,3]. Cervical cancer is disproportionately common in low-resource countries, which emphasizes the urgent need for reliable, easily available, and reasonably priced screening techniques to guarantee early identification and lower death rates.

Precise categorization of Cervical cancer is essential not only for identifying the illness but also for directing therapeutic choices and enhancing prognostic factors. For many years, liquid-based cytology and Pap smears have been the mainstays of cervical cancer prevention screening techniques. These techniques entail examining cervix-scraped cells under a microscope to look for precancerous alterations. These methods have drawbacks even though they work well. For example, the sensitivity range of Pap smears is 55-80%, which means that a sizable fraction of cases may be missed on the initial test. Although liquid-based cytology is more sensitive than traditional Pap smears, it still has limits with respect to specificity and interpretation, requiring a high level of skill. In response to these difficulties, increasingly sophisticated technologies have been created to enhance the precision and consistency of cervical cancer screening.

Recent developments in Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) have shown promise as methods to improve Cervical cancer diagnosis and classification. Computers may learn from data and make predictions or judgments without explicit programming thanks to machine learning, a subset of artificial intelligence. Deep Learning (DL) is a more sophisticated type of machine learning that uses multi-layered neural networks to automatically extract features from unprocessed input, such photographs. These technologies offer automated, highly precise, and scalable solutions that can overcome the drawbacks of conventional methods, potentially revolutionizing Cervical cancer screening. Devi et al., for example, investigated the use of different neural network topologies, such as multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), to enhance Cervical cancer classification. By automatically identifying pertinent features from medical images, these models have demonstrated potential in resolving the shortcomings of manual screening procedures, resulting in more consistent and accurate diagnoses [4]. The “NeuralPap System,” which combines cutting-edge image processing methods like Adaptive Fuzzy-k-Means clustering and Pseudo Color Feature Extraction, has shown promise in increasing classification accuracy from 73.40% to 76.35% [5]. While difficulties still exist with regard to computational efficiency and practical applicability, this system serves as an example of how deep learning might improve the accuracy of cervical cancer screening. Moreover, hybrid methods that fuse classical machine learning techniques with deep learning have demonstrated even more promise. For instance, a study that combined the deep learning model ResNet101 with the Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier reported an astounding 92% accuracy in identifying cases of mild to moderate dysplasia and 100% accuracy in differentiating between cases that were normal and abnormal [6]. This demonstrates the potential to improve and refine the final decision-making process by utilizing deep learning’s capacity to automatically extract features from complicated datasets and combining the advantages of conventional classifiers.

To fully achieve the promise of AI in cervical cancer categorization, however, a number of important obstacles and research gaps remain to be filled. While certain studies have reported high accuracy rates—for example, a Decision Tree classifier in a feature selection study reported 97.5% accuracy [7], or the Gauss-Newton representation-based algorithm (GNRBA) on a Kaggle cervical cancer database reported 93% accuracy [8]—these results are frequently derived from carefully selected datasets that might not accurately reflect the complexity and diversity of real-world clinical environments. A number of significant obstacles still stand in the way of the broad use of these technologies, including scalability, generalizability, and the capacity to function in real-time clinical situations. Furthermore, issues with missing values, imbalanced datasets, and computational efficiency make using AI models in clinical practice much more difficult.

Further research aimed at resolving these constraints is desperately needed as the fields of AI and ML continue to develop. This entails enhancing the resilience of current models through optimization, investigating novel techniques to manage sparse and unbalanced data, and guaranteeing that these technologies can be easily incorporated into a variety of clinical situations. The ultimate objective is to provide more precise, dependable, and easily available Cervical cancer screening technologies in order to convert these scientific breakthroughs into improved patient outcomes. So, with that keeping in mind, this research’s main contributions are-

• Implementing a proposed advanced DL model tailored to a given objective for the accurate classification of Cervical cancer.

• Eliminating overfitting, performance problems and create a powerful and reliable CervixCan-Net model for accurate image classification.

• Enhancing the classification tasks by improving safety and accuracy on histopathological images with our proposed model.

• Comparing the proposed model’s performance with other cutting-edge models using classification task performance metrics.

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. General Overview of the Method

The rest of the structure of the paper is as follows- After the Introduction, The Literature Review has been presented in Section 2. Following that, Section 3 addressed the Methodology. Results Analysis is presented in Section 4, and Discussion is presented in Section 5. Lastly, the Conclusion is presented in Section 6.

Various advanced neural network and ML methods are highlighted in the literature on cervical cancer categorization, with the goal of enhancing detection accuracy. Devi et al. investigated a variety of neural network topologies, including convolutional neural networks and multi-layer perceptron’s, to overcome the drawbacks of manual screening techniques like liquid cytology and Pap smears. By addressing the difficulties associated with early detection and the intricacies of cell structure, their work highlights the potential of artificial neural networks (ANNs) to improve detection rates and accuracy [4]. The “NeuralPa System” study improved classification accuracy from 73.40% to 76.35% by introducing novel image processing algorithms, such as Pseudo Color Feature Extraction and Adaptive Fuzzy-k-Means clustering. The study recognizes the need for improved computing efficiency and practical applicability notwithstanding these developments [5]. A different strategy that combined ResNet101 with a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier produced noteworthy outcomes, classifying mild and moderate dysplasia with 92% accuracy and differentiating between normal and abnormal cases with 100% accuracy. Further investigation is still needed to determine this system’s scalability and validity on a variety of datasets [6]. Additionally, a study that examined several feature selection and classification strategies found important predictive features and used a Decision Tree classifier to get a 97.5% accuracy rate. Even though this study was successful, it included drawbacks such as missing values and unbalanced data, indicating that more sophisticated methods should be investigated [7]. The efficiency and simplicity of the Gauss-Newton representation-based algorithm (GNRBA) were demonstrated when it obtained a 93% accuracy on a Kaggle cervical cancer database. However, more research is necessary due to the scalability and real-time clinical performance of GNRBA [8]. Devi et al.’s narrative review addresses feature-based classification strategies that center on nucleus shape, diameter, color, and luminosity. It highlights the need for more effective ways to process and categories multiple images at once because handling images one at a time is currently limited [9]. Significant advances over the past 15 years have been noted in a thorough assessment of image analysis and machine learning techniques for automated cervical cancer screening. Algorithms have achieved up to 99.27% accuracy in binary classification. Nevertheless, it highlights the lack of applicability in clinical settings in underdeveloped nations due to cost and skill constraints, as well as the limitations in classification accuracy for specific cell classifications [10].

Additionally, research employing K-Nearest-Neighbors (KNN) reports accuracy of 84.3% in the absence of validation and 82.9% in the presence of 5-fold cross-validation; nonetheless, they highlight difficulties associated with certain classification problems and scalability [11]. Studying multi-label classification techniques for early diagnosis highlights methodological limitations and the requirement for application in various clinical settings by contrasting algorithms such as Random Forest and Na¨ıve Bayes [12]. Associative classification method comparisons, like that between RCAR and CBA, demonstrate the superiority of the CBA model in a number of metrics, but they also point out the drawbacks of concentrating on just two approaches without taking into account other variables [13]. With up to 83% accuracy, texture analysis techniques for cervical cancer detection in MR images outperform more conventional diagnostic methods, highlighting its potential to enhance patient care [14]. Although the study’s concentration on particular cancer kinds restricts its generalizability, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have also showed promise, reaching 93.33% accuracy with original photos and 89.48% with enhanced images [15]. Automated methods have been developed, like the CerCan·Net model by Attallah and the modified fuzzy C-means algorithm by Wasswa et al., which both obtained good classification accuracy but need more validation for wider applicability [16,17]. Habtemariam et al.’s EfficientNetB0 likewise shown good test and validation accuracies, but it also revealed constraints related to dataset diversity and size [17]. Kurniawati et al. used Random Forest Tree, SVM, and Na¨ıve Bayes to show how important data preparation is for robust classification [18]. SVM was shown to be superior in the NTCC system created at Herlev University Hospital for classifying Pap smear images; however, it did not address computational complexity or real-time performance, which limited its practical deployment [19]. Moreover, using cervigram images, a research team’s fully automated deep learning pipeline for classifying cervical cancer demonstrated high accuracy and efficiency [20]. However, it also brought attention to the need for better classifier performance and real-time applicability, particularly in less developed areas. Although they achieved 91.46% accuracy, hybrid transfer learning approaches— such as those by William et al. employing pre-trained CNNs—were constrained by debates about computational resources and dataset specificity [21]. High accuracy was attained by Priya and Karthikeyan’s heuristic and ANN-based model, although they pointed out that generalizability and computational requirements were restricted [22]. Concerns with generalizability and the requirement for model interpretability were brought up in studies evaluating various machine learning algorithms for cervical cancer prediction, including Decision Tree, Naive Bayes, KNN, SVM, and MLP [23].

Furthermore, DeepCyto is a hybrid framework that uses deep feature fusion from pre-trained CNNs such as XceptionNet, VGGNet, and ResNet50. It was introduced by Shinde et al. Using datasets including the Herlev Pap Smear, Sipakmed Pap Smear, and LBC, this study obtained good classification accuracy; nevertheless, it also highlighted the need for optimization and addressing computing costs [24]. Using a dataset of 858 patients, Nithya and Ilango’s research demonstrated the value of feature selection techniques including the Boruta algorithm and Recursive Feature Elimination in accurately predicting cervical cancer. They emphasized moral obligations and pointed up restrictions with dataset specificity and computational complexity [25]. Using non-parametric losses like OE, CO2, and HO2, Frank et al. improved the multi-class classification of cervical cells by over 10% by proposing ordinal loss functions and utilizing the Herlev dataset. To address the complexity of overlapping nuclei, additional refining is necessary, according to the study [26]. Razali et al. concentrated on categorizing risk factors for cervical cancer through the use of data mining methods and algorithms, including k-Nearest Neighbours, Decision Trees, Naive Bayes, and Neural Networks. They used the UCI Machine Learning Repository dataset to test Random Forest and found that it produced the best results. They also noted that SMOTE and data imputation are crucial for managing imbalanced and missing value datasets [27]. Using the SIPaKMeD dataset, Pacal and Kılıcarslan investigated deep learning methods such as CNNs and vision transformers, obtaining strong classification results. Their research demonstrated how ensemble learning can improve classification outcomes and how ViT-B16 and EfficientNet-B6 models have improved accuracy [28]. With an AUC of 0.97, comparison research using cervicography pictures showed that ResNet-50 outperformed more conventional machine learning models, such as XGB, SVM, and RF, in terms of accuracy [29]. Using feature selection techniques, Priya and Karthikeyan’s ANN-based model obtained great accuracy; nevertheless, it was limited in its generalizability and computing requirements [22]. Using CNN-based models on supplemented datasets, Ishak et al. addressed data scarcity and observer variability and achieved notable gains in classification accuracy with augmented data [15]. The potential of texture features above conventional clinical criteria was highlighted by Nazim et al.’s use of texture analysis techniques in MRI imaging, which showed great accuracy in predicting cervical cancer stages [14].

In summary, this research highlights how automated systems, ANNs, and machine learning techniques are always evolving to improve the accuracy of Cervical cancer detection. Taken as a whole, they demonstrate notable progress in classification methods, attaining high accuracies with a variety of models like ResNet-50, ViT-B16, and EfficientNetB6, as well as novel strategies like hybrid transfer learning and DeepCyto. Even with these achievements, there are still significant research gaps that require attention. Among these include the need for additional studies to improve the approaches’ scalability, generalizability, and usefulness in a variety of clinical contexts. likewise, even though these models have attained excellent accuracies, ongoing refinement is necessary to enhance their robustness and classification performance, especially when dealing with imbalanced datasets, sparse data, and observer variability. The effective application of these techniques in actual clinical settings necessitates consideration of resource needs and computing efficiency. To ensure that these technology breakthroughs transfer into better patient outcomes and to enhance cervical cancer screening, it will be imperative to fill in these gaps through thorough validation, optimization, and investigation of novel approaches.

The primary focus of this work is the classification of Cervical cancer by comparison of various CNN models. Ensuring file accessibility, converting photos to JPG format, and resizing and padding them to standardize their size are the initial steps in the method’s data pre-processing. Then dataset was divided into testing, validation, and training. Augmentation techniques were omitted as the source dataset itself was of 25000 images. So, we did not feel the necessity to increase dataset diversity any further. The model architecture is the proposed model with preloaded ImageNet weights. After the top layer is removed, further levels are added using the Functional API. These layers consist of a final dense layer with softmax activation for multi-class prediction, dropout layers for regularization, dense layers with ReLU activation and kernel regularization, and global average pooling. The first 100 layers are frozen, while the remaining layers are then unfrozen, allowing the system to be adjusted to new weights. Adam optimizer and a categorical cross-entropy loss function are utilized for multi-class classification. Learning rate scheduling and early stopping functions reduce overfitting and maximize model training. In general, this strategy aims to maximize model performance by architecture adjustments and data augmentation, while simultaneously effectively classifying Cervical Cancer through the application of deep learning approaches.

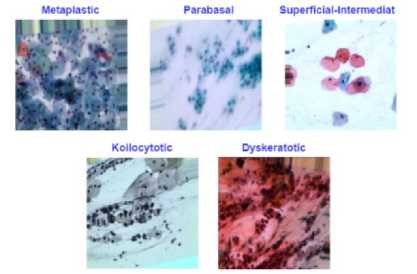

Fig.1. Sample images from dataset

-

3.2. Dataset Description

The dataset collected from https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/arjunbasandrai/medical-scan-classification-dataset, includes images of Cervical cancer diseases counting 25000 which are organized in five types of classes accordingly. They are- Dyskeratotic, Koilocytotic, Metaplastic, Parabasal, and Superficial-Intermediate while each class contains exactly 5000 images. As mentioned earlier, the dataset was divided into three parts- Train, Test, and Validation. So,

after several trial-and-error process, the dataset was divided in the following ratio: 70%-15%-15% for Train, Test, and Validation accordingly. Which means, 17500 images for Training, 3750 images for Test and the rest 3750 for Validation were used in our proposed model. Figure 1 shows the example images for these five subtypes of Cervical Cancer and the approximate distribution of images for the Train, Test, and Validation is also shown in detail in Table 1.

-

3.3. Proposed Model

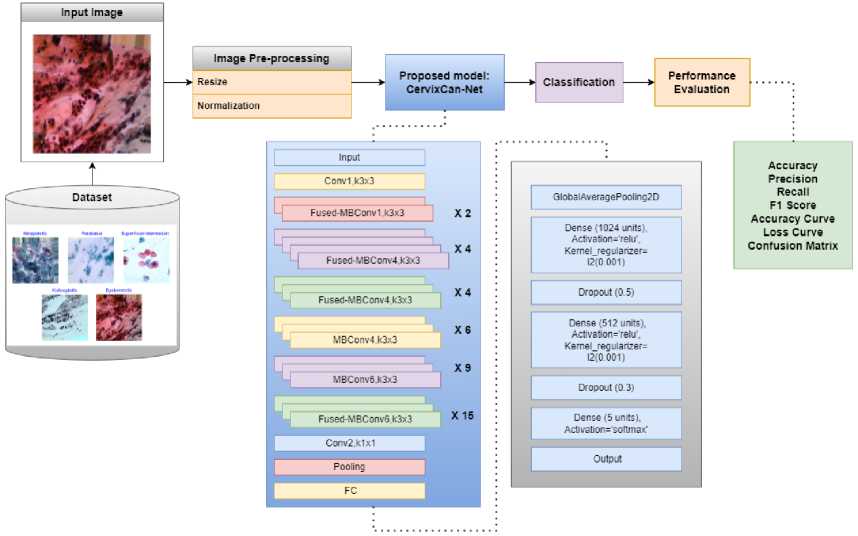

The proposed model’s overall architecture is shown in Figure 2, inspired by MobileNet as it performed better than other base models. Pre-processing steps included resizing images, converting files to a common format, and confirming file accessibility. However, data augmentation techniques were omitted for our proposed model as the image dataset that we have collected was itself 25000 in count. So, we did not see the necessity of making the dataset any larger or increase diversity any further. A standard ratio was used to split the dataset into training, validation, and testing sets in order to facilitate model evaluation and performance assessment. Using the state-of-the-art base model that was pretrained on ImageNet weights enabled effective classification tasks. This gave us access to a method that is efficient and also gave us standardized benchmarking approach together with tools for classifications evaluation.

Table 1. Image dataset distribution for each class

|

Class Name |

Train |

Validation |

Test |

Total Images |

|

Dyskeratotic |

3500 |

750 |

750 |

5000 |

|

Koilocytotic |

3500 |

750 |

750 |

5000 |

|

Metaplastic |

3500 |

750 |

750 |

5000 |

|

Parabasal |

3500 |

750 |

750 |

5000 |

|

Superficial-Intermediate |

3500 |

750 |

750 |

5000 |

|

Total |

17500 |

3750 |

3750 |

25000 |

Fig.2. Overview of proposed CervixCan-Net system’s architecture

The feature map dimensions at each layer were closely observed to guarantee appropriate transformations across the network and to offer a greater understanding of CervixCan-Net's architecture. While ReLU was used in the dense layers to increase computing efficiency, the Swish activation function was used in the convolutional layers to improve non-linearity. For improved convergence, weight initialization was done using the He initialization approach, and training was stabilized by integrating batch normalization. Adaptive optimization was ensured by configuring the learning rate scheduler, ReduceLROnPlateau, with a reduction factor of 0.1 and a patience value of 3. 5.0 threshold gradient clipping was used to keep gradients from blowing up. Selective trainable layers were used to optimize performance while preserving computational efficiency in the pre-trained base model, EfficientNetV2.

CervixCan-Net, our proposed model, is built with layers intended to improve classification accuracy. We used data-streaming techniques to reduce the size of feature maps. We then included techniques to avoid overfitting and added layers to extract higher-level characteristics. We enhanced the model’s capacity for generalization and decreased the likelihood of overfitting by arbitrarily deactivating specific neurons during training. Last but not least, the algorithm can forecast the probability that a picture falls into one of the five categories for Cervical cancer, guaranteeing precise and reliable outcomes.

The hyperparameters that were used to train the convolutional neural network model CervixCan-Net provide details about the ideal configuration for categorizing Cervical Cancer, which is provided in Table 2. The model architecture has around 6.93 million parameters and six levels. In the brain, the next three layers are completely linked layers, while the first three are 3x3 convolutional filters. The training data is normalized to a resolution of (224, 224) with three channels and the images are scaled to (625, 450) as a result of preprocessing. The model is trained with the Adam optimizer, using 0.0001 as the configurable learning rate. Learning is controlled using the ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler and the EarlyStopping technique. For multi-class classification, the categorical CrossEntropy loss function is employed, with a label smoothing default of 0.1. Techniques for regularization include L2 kernel regularization and dropout rates of 0.5 and 0.3. The activation functions Swish and ReLU are used differently throughout the network. The classifier uses batches of size 12 and the softmax function to calculate probabilities across a maximum of 15 epochs during training, enabling class prediction for the five Cervical Cancer classes.

Table 2. Hyper parameters for the proposed cervixcan-net model

|

Hyper Parameters |

Hyper Parameter Values |

|

Model |

CervixCan-Net |

|

Params |

6.93 million |

|

Convolution Size |

3x3 |

|

Head |

3 |

|

Layers |

6 |

|

Training Resolution |

(224, 224) |

|

Number of Channels |

3 |

|

Number of Classes |

5 |

|

Scaling |

Resize (625, 450) |

|

Optimizer |

Adam |

|

Learning Rate |

Adaptive, 0.0001 (at beginning) |

|

Scheduler |

ReduceLROnPlateau, EarlyStopping |

|

Loss |

Categorical CrossEntropy |

|

Label Smoothing |

0.1 by Default |

|

Pre-processing |

Normalization & Resizing |

|

Regularization |

Dropout = 0.5, 0.3 | Kernel Regularizer = L2 |

|

Activation |

Swish, ReLU |

|

Max Epoch |

15 |

|

Batch |

12 |

|

Classifier |

Softmax |

And we acknowledge the crucial necessity of interpretability techniques for medical applications, even though they were not included in our work. In order to improve the transparency of CervixCan-Net's predictions, future research will concentrate on incorporating visualization techniques as SHapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) and Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) as it shows great localization capabilities [30]. By emphasizing the areas in input photos that affect the model's conclusions, these methods would offer visual explanations for the classification results. By helping physicians determine whether the model's focus is in line with medically relevant qualities, these tools could build trust and make the model a trustworthy diagnostic tool. Furthermore, the model's decision-making process may be in line with clinical knowledge if the regions found by these methods are compared to areas annotated by experts. Investigating these approaches will enhance the interpretability and clinical applicability of CervixCan-Net in future research.

-

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

We used a number of assessment criteria, including Accuracy (Acc), Precision (Pre), Recall (Rec), and F1 Score, to assess the effectiveness of our implemented models and compare them with our proposed CervixCan-Net. Not quite a performance measure, but we also created a confusion matrix, which is the source of other metrics. The disparity between the projected labels and the ground truth labels is visually displayed in the confusion matrix. The confusion metric’s rows define examples in a predicted class, whereas its columns describe cases in an actual class. False Positive (FP), False Negative (FN), True Positive (TP), and True Negative (TN) are terms that rely on the confusion matrix.

A detailed explanation of the mathematical terms such as Precision (Pre), Recall (Rec), Accuracy (Acc), and F1 Score is provided below where-

TP = The number of positive class samples that were accurately predicted by the model.

TN = The number of negative class samples that were predicted by the model.

FP = Indicates the number of negative class samples that were not predicted correctly by the model.

FN = A number of positive class samples that were not correctly predicted by the model.

F1 Score =

Precision+Recall

Overall, the study offers a thorough method for enhancing Cervical cancer focusing on integrating CervixCan-Net with additional layers to improve representation using the image dataset. The proposed method emphasizes the CervixCan-Net hyperparameter configuration for Cervical cancer classification by utilizing DL on the image dataset.

4. Result Analysis 4.1. Environmental Setup

Table 3. Environment setup summary for the models' implementations

|

Model Name |

GPU Name |

Batch Size |

Optimizer, Learning Rate |

Epoch |

Activation Function |

Data Augmentation |

|

DenseNet201 |

NVIDIA TESLA T4 |

224x224 |

Adam, lr:0.0001 |

15 |

ReLU |

Not Applied |

|

MobileNet |

NVIDIA TESLA T4 |

224x224 |

Adam, lr:0.0001 |

15 |

ReLU |

Not Applied |

|

MobileNetV2 |

NVIDIA TESLA T4 |

224x224 |

Adam, lr:0.0001 |

15 |

ReLU |

Not Applied |

|

NASNet |

NVIDIA TESLA T4 |

224x224 |

Adam, lr:0.0001 |

15 |

ReLU |

Not Applied |

|

ResNet50 |

NVIDIA TESLA T4 |

224x224 |

Adam, lr:0.0001 |

15 |

ReLU |

Not Applied |

|

VGG16 |

NVIDIA TESLA T4 |

224x224 |

Adam, lr:0.0001 |

15 |

ReLU |

Not Applied |

|

VGG19 |

NVIDIA TESLA T4 |

224x224 |

Adam, lr:0.0001 |

15 |

ReLU |

Not Applied |

|

Xception |

NVIDIA TESLA T4 |

224x224 |

Adam, lr:0.0001 |

15 |

ReLU |

Not Applied |

|

InceptionV3 |

NVIDIA TESLA T4 |

224x224 |

Adam, lr:0.0001 |

15 |

ReLU |

Not Applied |

|

EfficientNetB3 |

NVIDIA TESLA T4 |

224x224 |

Adam, lr:0.0001 |

15 |

ReLU |

Not Applied |

|

Proposed CervixCan-Net |

NVIDIA TESLA T4 |

224x224 |

Adam, lr:0.0001 |

15 |

ReLU |

Not Applied |

A detailed overview of the environment configuration used to train several CNN models is shown in Table 3. Important details such as Model Name, GPU Name, Batch Size, Optimizer, Learning Rate, Epoch, Activation, and Data Augmentation are included in table rows that are linked to specific models. Interestingly, all models were trained on the NVIDIA TESLA T4 GPU with a constant batch size of 224x224 and a maximum of 15 epochs. Each model was subjected to the activation function ReLU in a consistent manner to introduce non-linearity into the network. The CervixCan-Net model, which was proposed, employed Adam with an adaptive learning rate that starts at 0.0001, while some models used the Adam optimizer with a fixed learning rate of 0.0001. It’s interesting to note that data augmentation was limited to the training stage of the proposed model, with the intention of introducing random alterations to enhance the model’s generalization and robustness. This configuration provides vital insights into the normal setting for CNN model training in the context of Cervical Cancer classification, which helps with repeatability and comparison across various experiments and architectures.

-

4.2. Result Analysis

Significant variations in accuracy metrics were discovered by contrasting the performance of several algorithms with histopathology data on a Cervical Cancer subtype dataset in Table 4. Among the assessed models, EfficientNetB3, MobileNet, MobileNetV2, and DenseNet201 displayed respectable testing accuracies of 83% to 91.61% and acceptable validation accuracies of 79% to 97.66%. However, MobileNetV2 significantly underperformed across the board, indicating challenges with accurately classifying Cervical Cancer subtypes. DenseNet201 demonstrated competitive results with a testing accuracy of 88.54% and a validation accuracy of 93.68%, outperforming the other models under examination.

Table 4. Model accuracy comparison for cervical cancer classification

|

Model Name |

Validation Accuracy |

Test Accuracy |

|

DenseNet201 |

93.68% |

88.54% |

|

MobileNet |

97.66% |

91.61% |

|

MobileNetV2 |

96.72% |

89.17% |

|

NASNet |

80.84% |

73.98% |

|

ResNet50 |

57.14% |

46.44% |

|

VGG16 |

90.36% |

81.27% |

|

VGG19 |

86.68% |

76.75% |

|

Xception |

89.46% |

80.16% |

|

InceptionV3 |

90.35% |

75.77% |

|

EfficientNetB3 |

79% |

83% |

|

Proposed CervixCan-Net |

100% |

99.83% |

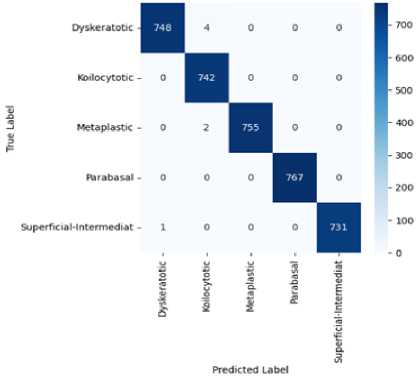

Fig.3. Confusion Matrix of proposed CervixCan-Net model

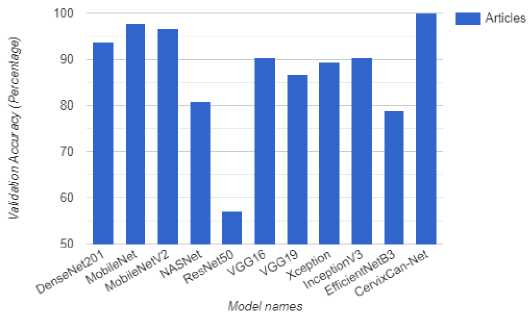

The proposed model, CervixCan-Net, performed better than all the others, with validation and testing accuracies of 100% and 99.83%, respectively. This remarkable outcome shows how well the proposed methodology can categorize Cervical Cancer subtypes based on the histopathology dataset and illustrates its efficacy. An analysis on the confusion matrix from Figure 3 also shows that the proposed model CervixCan-Net performed quite well in terms of identifying images accurately. Important information about CervixCan-Net's performance in each of the five types of cervical cancer—dyskeratotic, kilocytotic, metaplastic, parabasal, and superficial-intermediate—can be found in the confusion matrix Figure 3. The high values along the diagonal show that the model can accurately categorise cases in all classes, which is noteworthy. The Dyskeratotic class, for instance, demonstrated little misclassification with 748 accurate predictions out of 752 cases. Likewise, 767 accurate predictions with no misclassifications were made by the Parabasal class. Other classes, however, show minor misclassifications. For example, four cases of the Koilocytotic class were incorrectly classified as Dyskeratotic. Two samples of the Metaplastic class have also been incorrectly categorized. The overlapping features in the image data between these classes may be the cause of these errors; this might be fixed in subsequent cycles by using data augmentation techniques to boost class-specific diversity or by implementing sophisticated feature engineering. The confusion matrix indicates places where additional modifications could improve precision while confirming that the model functions robustly across all classes. In order to further reduce errors in minority or closely overlapping groups, future work could concentrate on correcting these misclassifications by applying data augmentation, using more diverse datasets, or using strategies like cost-sensitive learning.

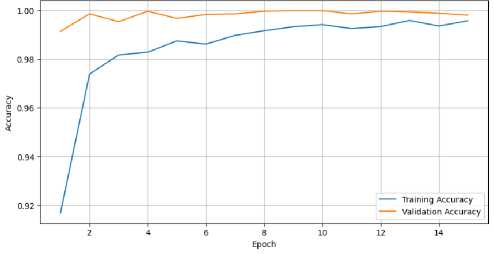

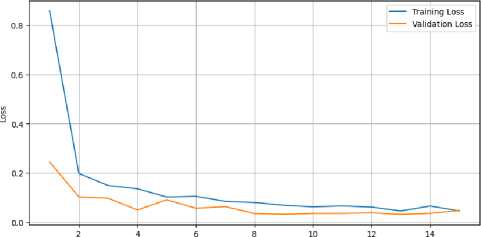

Nevertheless, every model that was altered produced favorable outcomes. Overall, the CervixCan-Net model performed the best. The confusion matrix diagram’s diagonal blue hues represent the model’s fraction of properly predicted values relative to the ground truth value. To better clarify our model, Figures 4 and 5 show the accuracy and loss curve outputs.

When compared to previously built base models, the CervixCan-Net model offers important new information about how well deep learning architectures work in medical imaging applications. The recommended model shows promise for improved diagnostic accuracy by outperforming the base models in terms of accuracy, F1 score, recall, and precision. This superiority suggests that the CervixCan-Net model has higher sensitivity and specificity than its rivals because it can identify intricate patterns and variables associated with Cervical Cancer diagnosis. Furthermore, the suggested model not only has improved convergence but also has the ability to reduce overfitting, indicating that it can robustly generalize to unknown data, according to the examination of training and validation loss across epochs. These findings demonstrate how tailored deep learning models may help increase the accuracy and consistency of Cervical cancer diagnosis.

Fig.4. Training and validation accuracy of proposed CervixCan-Net model over epochs

Fig.5. Training and validation loss of proposed CervixCan-Net model over epochs

The performance test of the CervixCan-Net model against a collection of well-known base models emphasizes how crucial architectural design choices are to optimizing the accuracy of Cervical Cancer classification. This targeted approach not only yields improved performance metrics but also highlights the importance of domain-specific model development for medical imaging applications. The CervixCan-Net model has demonstrated superior performance compared to its competitors in various domains such as accuracy, F1 score, recall, and precision. This underscores the necessity of ongoing research and innovation aimed at enhancing these models for practical application in clinical settings. Furthermore, it validates the potential of deep learning techniques to revolutionize the field of cancer diagnostics. In order to further clarify our model, Figures 6, and 7 show the Test Accuracy, and validation Accuracy graphs in comparison to other models.

Although formal statistical testing was not performed, CervixCan-Net's performance has demonstrated dependable and consistent outcomes across several runs. The model showed minimal volatility between test sets and good accuracy and F1-scores. These findings imply that the model's performance is consistent and not the result of chance. We do recognize the value of statistical validation, though, and future research will take these techniques into account to further substantiate the model's performance's resilience. A detailed examination of model accuracies and performance metrics for Cervical cancer classification tasks with previous researches is given in Table 5. It contains several well-known models from earlier research as well as the proposed CervixCan-Net model. It is interesting to note that the proposed model outperforms previous studies by achieving an outstanding accuracy of 99.83%, while the past works yielded reasonable accuracy between 93.33% and 99.2%. Moreover, the proposed model performs extraordinarily well in terms of accuracy, recall, and F1 score, with a precision of 99.80%, recall of 99.80%, and an F1 score of also 99.80%. This highlights the CervixCan-Net model’s advantages and efficacy, making it a superior choice for picture classification issues.

|

Test Accuracy Comparison for Cervical Cancer Classification with proposed model and base models 100 --------------------------------_ lllhllllll Model names Fig.6. Test accuracy comparison for cervical cancer classification with proposed model and base models |

| Articles |

Validation Accuracy Comparison for Cervical Cancer Classification with proposed model and base models

Fig.7. Validation accuracy comparison for cervical cancer classification with proposed model and base models

Table 5. Model accuracy comparison between existing models with proposed CervixCan-Net model

|

Ref. |

Model |

Test Accuracy |

Precision |

Recall |

F1 Score |

|

[2] |

PCA |

99.2% |

- |

100% |

99.27% |

|

[8] |

SVM |

93.671% |

98.013% |

95.484% |

96.732% |

|

[27] |

Enhanced Fuzzy C-means |

98.88% |

97.47% |

99.28% |

- |

|

[28] |

DCNN |

93.33% |

- |

- |

- |

|

[31] |

K-nearest Neighbor |

- |

96% |

95% |

94% |

|

Proposed Model |

CervixCan-Net |

99.83% |

99.80% |

99.80% |

99.80% |

5. Discussion

With an astounding 99.83% accuracy rate in Cervical Cancer classification, the CervixCan-Net model represents a major advancement in medical imaging. This accomplishment surpasses well-known CNN designs like InceptionV3 and DenseNet201, setting a new standard rather than merely being a step in the right direction. Not only does the model perform better, but it also shows how revolutionary modern deep learning systems may be in the field of medical diagnosis. With layers like Global Average Pooling 2d, a Dense layer of 1024 units, Dropout, another Dense layer of 512 units, additional Dropout, and a final Dense layer of 5 units, the model’s architecture is a testament to careful design. The Dense layers are complemented by L2 Kernel Regularizers. The improved performance parameters of the model, including as accuracy, recall, precision, and f1 score, are greatly enhanced by these layers. The model’s effectiveness has been largely attributed to the inclusion of the Adam optimizer, the ReLU and Softmax activation functions, and the categorical cross-entropy loss function. These decisions show a dedication to reaching an efficacy level that distinguishes the CervixCan-Net approach. Additionally, by improving the EfficientNetV2 framework, it produces accurate and reliable results with fewer computational resources needed than competing models. The model has the potential to make a substantial contribution to the field of medical diagnostics, as evidenced by its balance of accuracy and efficiency. The model has the potential to greatly improve the accuracy and reliability of diagnostics because of its skill in identifying complex patterns and factors that are essential for Cervical Cancer diagnosis. With new insights and chances to improve patient outcomes in the management of complicated illnesses like Cervical Cancer, the model’s ground-breaking results signal the beginning of a new era in precision medicine. Thus, the CervixCan-Net model’s performance illustrates the significant influence that cutting-edge DL models can have on medical imaging and healthcare diagnostics, pointing the way in the direction of improved diagnostic precision and more individualized treatment strategies in the future. Furthermore, the results and lack of a significant computational overhead demonstrate the differences between this model and other models, highlighting the strength of our model’s ability to produce excellent results while retaining efficiency and using fewer resources. Even while models like MobileNet might be more effective, they are still unable to match CervixCan-Net’s level of performance. However, there still remains a research limitation as our proposed CervixCan-Net model did not use any augmentations because of limited resources and computational powers. Also, the dataset’s duplicity was not tested. This could be the reason why our validation accuracy was 100%.

Although the size of the dataset prevented us from including data augmentation, we acknowledge that this decision may provide biases and overfitting hazards. In order to address these issues, we improved the model's capacity for generalization by implementing a number of regularization strategies, such as L2 kernel regularization and dropout layers with rates of 0.5 and 0.3. Furthermore, EarlyStopping and the ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler were used to guarantee ideal training without overfitting. In order to further increase model resilience and lessen any potential skewness in data representation, we admit that dataset biases may still exist and advise future research to use thorough bias analysis and data augmentation techniques such rotation, flipping, or brightness modifications as it also has the potential to improve generalizability. Additionally, class imbalances are frequent in real-world applications, where some conditions could be more uncommon than others. Future research will investigate a number of approaches to overcome this, such as balancing the representation of rare classes in the training data by under sampling or oversampling techniques like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique). To further prioritize under-represented classes during training, class-weighted loss functions—like weighted categorical cross-entropy—will be implemented. In order to assess the model's performance and resilience in situations when class imbalance is more noticeable, we also intend to test it on artificial or unbalanced datasets. The goal of these initiatives is to guarantee that, even when handling uncommon circumstances, the model retains its high level of accuracy and fairness. Also, CervixCan-Net and other medical AI applications must address privacy, biases, and ethical issues. Strict compliance with laws like GDPR and HIPAA is necessary to ensure data privacy, and patient data must be anonymized to safeguard sensitive information. Because imbalances or biases in the dataset may result in differences in model performance across various population demographics, bias mitigation is equally crucial. This could limit the model's usefulness in a variety of clinical contexts. To guarantee equity and inclusion, testing on a variety of datasets should be a part of future research. Moreover, the ethical implementation of CervixCan-Net should emphasize the model's usage as a supplemental diagnostic tool to support expert judgement rather than replace it, encouraging collaborative decision-making for physicians. So, further research focusing on the above mentioned terms is a must.

6. Conclusions

Considering the research on Cervical cancer classification using advanced CNN-based models, it may be concluded that deep learning has the potential to disrupt medical imaging. Our proposed CervixCan-Net model, which has an accuracy rate of 99.83%, is a prime example of innovation in this study. This success has brought to light the critical role that cutting-edge methods play in increasing the efficacy and precision of cancer diagnosis as well as offering effective avenues for early detection and treatment. Comparing the architecture with popular CNN designs like DenseNet201, NASNet, ResNet50, Xception, MobileNet, MobileNetV2, VGG16, VGG19, EfficientNetB3, and InceptionV3 has provided valuable insights into the evolution of image classification techniques. While industry standards have typically been set by these basic models, our model’s enhanced performance signals a paradigm shift in the field of medical image analysis. Its improved performance over these well-known architectures has brought attention to the development of deep learning as a more accurate and reliable method of Cervical cancer diagnosis. Insight into the future of precise medicine, particularly in the treatment of complex illnesses like Cervical cancer, has been promisingly supplied by the development of the CervixCan-Net model. Better patient outcomes and maybe lower rates of Cervical cancer related mortality could arise from the ongoing improvement of sophisticated CNN-based models.

In this study, we mainly compared CervixCan-Net with academic CNN designs, which are known benchmarks in medical imaging research, including DenseNet201, InceptionV3, and MobileNet. We do, however, recognize the significance of comparing the model's performance against competing AI solutions designed for cervical cancer diagnosis as well as real-world clinical standards. Although there aren't many publicly accessible AI solutions for classifying cervical cancer, future research will entail partnerships with clinical institutions to compare CervixCan-Net to already available diagnostic instruments utilized in clinical practice. To give a more thorough evaluation of the model's effectiveness, this comparison will take into account both AI-driven and conventional diagnostic techniques. Furthermore, in order to assess the model's resilience, scalability, and suitability for a range of clinical procedures, we intend to investigate external datasets and real-world applications. And we do recognize that testing the model on real-world, unseen data from a variety of demographics is crucial. In order to guarantee the model's applicability across a range of people, future research will broaden to include datasets from other demographics and geographical locations, even though our current work concentrated on a single dataset. The generalizability of the model will also be evaluated through external validation on separate datasets. This will give a more thorough grasp of how well the model performs in practical situations and assist in locating any biases or restrictions that might appear when used with larger datasets as the future of healthcare appears bright, with deep learning at the forefront of delivering revolutionary breakthroughs in medical diagnosis. As AI research in healthcare advances, these developments have the potential to transform clinical practice, encouraging a more efficient and effective approach to disease management.