Chalcolithic and Bronze Age (4th to 3rd millennia bc) burials with gold ornaments in the Caucasian Mineral Waters area

Автор: Korenevskiy S.N.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145426

IDR: 145145426 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.2.024-032

Текст обзорной статьи Chalcolithic and Bronze Age (4th to 3rd millennia bc) burials with gold ornaments in the Caucasian Mineral Waters area

Gold and silver have played an outstanding role in the establishment of civilization and the state economy. At the same time, they were indicators of the high social prestige of their owners even in the pre-state period, being closely related to magical and cult beliefs. Their specific reflection in the burial rites of various Chalcolithic and Bronze Age cultures is an issue that requires special study. In this article, we consider assemblages with artifacts of gold on the basis of materials from the sites of the 3rd millennium BC in the Caucasian Mineral Waters area, against the background of gold’s wide distribution in Ciscaucasia in previous times.

Description of assemblages

As is known, gold was widely used by the tribes of the Maikop-Novosvobodnaya cultural community (MNC) in their burial rites in the 4th millennium BC. Both unique and widespread ornaments made of gold are encountered: diadems, flowers, rings, temple pendants, bead necklaces, and needle-shaped rods. Highly artistic casting and stamping of plates in the forms of figures of bulls and lions are noted. Gold and silver vessels, and gold cover plates on weapons are known. In general, finds of gold were recorded in more than 40 burials (Korenevskiy, 2011: 94–100).

Analysis of occurrences of gold items together with weapons and tools in the Maikop burials has shown

that they are most frequently present in assemblages containing a set of a bronze axe, an adze, a chisel, a dagger, and metal ware (100 or 80 %, 10 cases out of 10 or 14, depending on the recording of assemblages with relatively good preservation); with weapons and woodworking tools, but without metal ware (62 %, 11 cases out of 16); and more rarely in burials with sets consisting of weapons only (38 %, 23 cases out of 59). Gold items are extremely rare (about 2–3 %) in burials without weapons, which are in the majority (more than 130 recorded cases as of 2011). Furthermore, such burials may be interpreted as female (for example, Kudakhurt, kurgan 1, burial 1) (Korenevskiy, 2017: 82–85).

On the basis of the occurrence of gold items in the MNC assemblages, a gradation of burial symbols was proposed. Assemblages containing more than two gold items were considered indicators of super-elitist* ranking; those with one or two gold ring pendants, indicators of initial-elitist ranking; and those without items made of precious metals, indicators of egalitarian funerary practices.

The phenomenon under consideration is thought to be a society of farmers and cattle breeders, wherein the military tribal nobility regularly emphasized in burial rites their prestige, according to the death mythology, with gold ornaments, steadily ignoring bronze ones, and using silver only in rare cases. An abundance of gold in certain graves allows us to estimate such marking as super-elitist or initial-elitist. The most significant MNC burials (with sets of weapons and implements) are related exactly to the super-elitist symbolism.

The MNC can be regarded as a military-elitist model of a prepolitarian (‘pre-state’) society (the term proposed by Y.I. Semenov) with the military and production (carpentry) symbolism of burial goods. A special feature of the prepolitarian stage of the early period of pre-state development (Semenov, 1993: 586) implied that the highest nobles were interested both in military prestige and job prestige. Therefore, they used symbols of tools as indicators of their extraordinary position, according to their ideas of the structure of the otherworldly realm of ancestors (Korenevskiy, 2004: 78–82; 2011: 125–136; 2017: 82–85).

Early in the 3rd millennium BC, MNC tribes disappeared in the Caucasus. Quite different archaeological cultures appeared in Ciscaucasia. Strong cultural transformations can also be traced in the Southern Caucasus. Finds of gold are rarely encountered in the funerary assemblages of this period in Ciscaucasia. They are represented mainly by headpieces in the form of

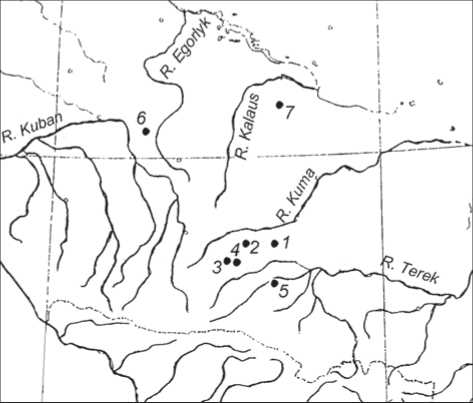

Fig. 1 . Locations of burials with gold pendants, mentioned in the text.

1 – Lysogorsky-6 cemetery; 2 – a kurgan near the wine-making state farm “Mashuk”; 3 , 4 – kurgans near the Nezhinsky village;

5 – Chegem II cemetery; 6 – Rasshevatskaya-1 cemetery; 7 – Sharakhalsun-3 cemetery.

small rings. Rings or coils of silver are also found. Most frequently, headgear ornaments were made of bronze.

Below, we shall consider the most spectacular assemblages with gold artifacts in the Caucasian Mineral Waters group of sites of the North Caucasian culture (Fig. 1). Many ornaments of bronze have been found in the burials of this group. It has been established that bone and bronze pins, and bronze plaques, are related to female burials, as is the case with the assemblages of Ciscaucasian Early Catacomb cultures, while stone maces and axes are related to male ones (Korenevskiy, 1990: 71–81; 2018). The latter were found in more than 25 cases. A bronze axe in the assemblages of the Caucasian Mineral Waters group is the single specimen. It was found in burial 4, kurgan 3 of the Lysogorsky-6 cemetery, in the Georgievsky District of the Stavropol Territory.

ranking is a rarity for the 5th to 4th millennia BC. The relevant information is related mainly to such cultures as Varna in the Danube region, the Ghassulian culture in Israel, the MNC in Ciscaucasia, and the Leyla-Tepe culture in the Southern Caucasus.

Ordinary-elitist or initial-elitist ranking in the 5th millennium BC is encountered in the same cultural formations. In Eastern Europe, single gold ornaments in the form of coils were found at Chalcolithic funerary sites of the Northern Pontic Region (Giurgiule§ti, burial 4). Subsequently, such marking of assemblages by silver (more rarely, gold) pendants is known in many regions of Northern Eurasia up to the Late Bronze Age (Korenevskiy, 2017: 124, 125). Egalitarian traditions of funerary practices are not related to egalitarian relationships in society, they are only illustration of cults and beliefs.

This burial was excavated during the rescue works by T.A. Gabuev and Y.B. Berezin in 2015 (Gabuev, 2015; Korenevskiy, Berezin, Gabuev, 2018).

Kurgan 3 at Lysogorsky-6 was the largest one not only in this cemetery, but also within a radius of several tens of kilometers. Its height is 7.2 m, the size along the eastwest line is 63 m, and along the north-south line 50 m. The kurgan contained four burials. Burial 4 was the main one. It belongs to the Middle Bronze Age, while the others to the Early Iron Age.

The burial structure had a complex construction. First, a shallow but vast pit with ledges was excavated in the layer above bedrock. Its dimensions were 6.70 × × 6.06 m along the upper edge, and 4.44 × 3.83 m along the bottom. The soil removed from the pit was thoroughly spread around in a ring. Then, a wooden chest 2.6 × 1.6 m in size was deposited in the pit. A dead body was laid there in an extended supine position, with the head towards the west. The chest had a wooden covering. Above it, masonry with a deer antler inside was arranged. Two crania of bulls were placed at two locations above the masonry. Finally, an earthen tumulus was constructed. Thus, over grave 4, a tremendous mound was formed, equal in its size to the mounds over the burials of MNC nobility.

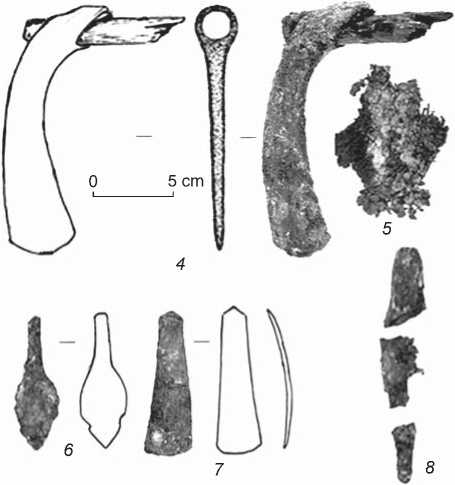

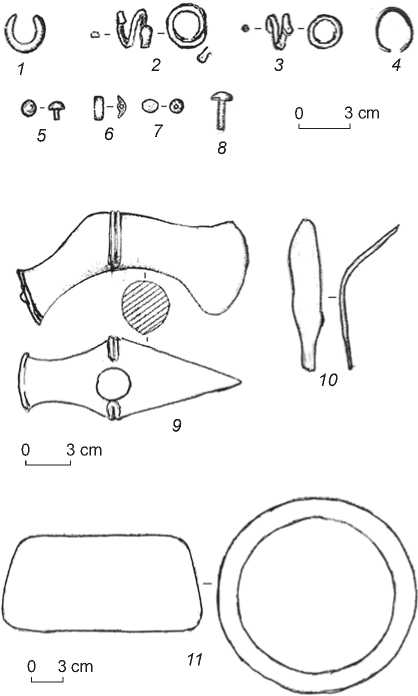

The burial goods of the assemblage under consideration are out of the ordinary. The headgear ornament is a gold ring-pendant 1.5 cm in diameter (Fig. 2, 1). A set of bronze ornamental pendants (a bracelet?) and beads (Fig. 2, 3) was at the lower portion of the right-hand humerus. The exact shapes and sizes of the artifacts cannot be restored. Another bronze bracelet is recorded on the carpal bones of the left hand. Its components are severely corroded, and were broken down during cleaning. One more beaded bracelet was found on the right ankle. It consists of bronze cast pendants (4 spec.) comprising a rod with a suspending hole in the upper portion, and balls in the lower one (Fig. 2, 2). The length of the remaining pendant is 3.6 cm.

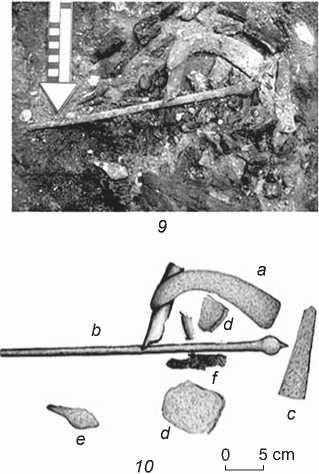

Near the wing of the left iliac bone of the buried person, there was a group of items lying on wooden dish or tray No. 1 (Fig. 2, 9 , 10 ). The tray (dish?) itself is poorly preserved, and is represented by separate fragments. Its exact shape is impossible to reconstruct. The tray had a flange along the edge. The diameter of the item’s remains is about 35 cm. The set of bronze artifacts on the tray included an arched battle-axe of the Nacherkezevi type (Korenevskiy, 1981: 25) (Fig. 2, 4 ), a small (7.2 cm long) leaf-shaped dagger (Fig. 2, 6 ), an adze 11.5 cm long (Fig. 2, 7 ), a rod 38 cm long (Fig. 3, 1 ), and a beaker. The beaker is represented by three fragments. Reconstruction of the beaker suggests that it was flat-bottomed, had a height of 110 mm, a bottom diameter of 66 mm, and a mouth diameter of about 70 mm, and its capacity was similar to that of a glass designed for 200 ml of liquid (Fig. 3, 2 ).

Wooden dish No. 2 was placed between the kneejoints of the buried person. Only a decayed portion 17 cm in diameter was preserved. A bronze item, fully corroded and broken down, was lying on it. Wooden tray

Fig. 2 . Goods from burial 4, kurgan 3 of the Lysogorsky-6 cemetery.

1 – a gold pendant; 2 – segments of an beaded ankle-bracelet; 3 – details of a beaded hand-bracelet; 4 – a bronze axe with a wooden handle; 5 – cloth; 6 , 8 – bronze daggers; 7 – a bronze adze; 9, 10 – items on tray No. 1, a photo and a drawing: a – an axe, b – a rod, c – an adze, d – a beaker, e – a dagger, f – cloth (after (Korenevskiy, Berezin, Gabuev, 2018)).

Fig. 3 . Finds from burial 4, kurgan 3 at Lysogorsky-6 ( 1 – 8 ), and burial 1, kurgan 5 of Nezhinsky group II ( 9 ).

1 – a bronze rod; 2 – reconstruction of a bronze vessel; 3–5 – fragments of this vessel; 6–8 – stone abraders; 9 – a fragment of wooden staff with bronze nails and a bronze awl. 1–8 – after (Korenevskiy, Berezin, Gabuev, 2018); 9 – after (Korenevskiy, 2018).

No. 3 was located 0.20–0.25 m to the south of the right thigh-bone of the buried, near the southern wall of the wooden structure. It was placed with its long axis along the east-west line. The artifact is up to 40 cm long and about 15 cm wide; its shape cannot be restored. This tray is associated with three stone abraders (Fig. 3, 6–8 ) and a severely corroded bronze dagger preserved in fragments, up to 12 cm long. Cloth-fragments were collected under the skeleton (see Fig. 2, 5 ). The radiocarbon date of the burial is 2861–2581 BC (4122 ± 23 BP, MAMS-29825) (The Genetic Prehistory…, 2018), which corresponds to the Early Dynastic period in Mesopotamia.

The second example of assemblages with gold pendants in the Caucasian Mineral Waters group is burial 5, kurgan 1 near the wine-making state farm “Mashuk” in the neighborhood of the city of Pyatigorsk (Afanasiev, 1975). The burial was the main one. It was constructed on the earth’s surface. The burial site, 3.55 × 2.00 m in size, was lined with a smooth layer of ragged stones and contoured along the perimeter by a stone skirting-board 20 cm high, composed of two rows of tiles. It was oriented with its long axis along the eastwest line. The entire site was covered with charcoal. The skeleton of an adult man was found on it, in an extended supine position, with his head towards the west. A stone mound 3 m high and 19 m in diameter was erected above the grave. Then, it was covered with a black-earth tumulus. In total, the kurgan height reached 4.5 m. It contained another three burials of the Caucasian Mineral Waters group, which were located at the circumference beyond the limits of the heap of stones; and one burial likely belonging to a later period.

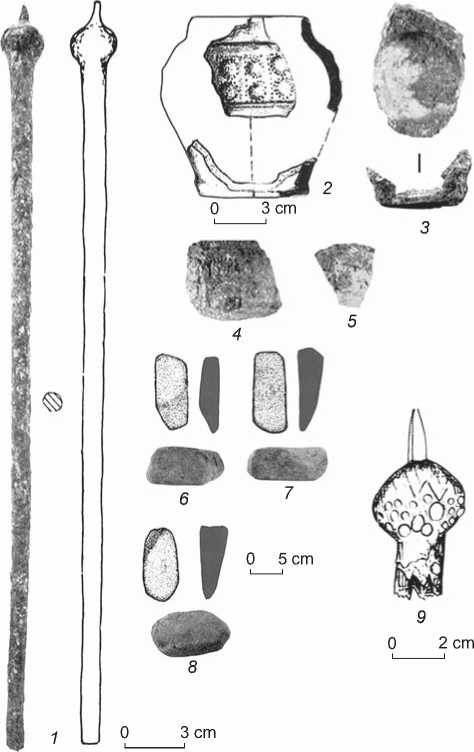

Near the skull of the buried, there were two pendants—one-turn rings: a gold one 1 cm in diameter (Fig. 4, 1 ) and probably a silver one (poorly preserved). Two bronze barrel-like beads 1 cm long and 0.6–0.7 cm in diameter (Fig. 4, 7 ) were found in the neck area. A smooth stone axe of the Kabardino-Pyatigorsk type was lying near the bones of the right hand (Fig. 4, 9 ). A bronze-headed nail was preserved in the opening for the haft element (Fig. 4, 8 ). Its length is 3.4 cm, the head’s diameter is 1.7 cm, and the shank’s diameter is 0.4 cm. A bent dagger with a tanged handle was near the axe (Fig. 4, 10 ). Its length is 16 cm. 16 bronze rivets in the form of pins 0.8 cm long with hemispherical heads were recorded in the belt area (Fig. 4, 5 ). Obviously, these were strap cover plates. Also, 12 segment-like pipe-shaped beads (Fig. 4, 6 ), made of low-grade silver,

were found here (according to the report). The length of a pipe-shaped bead is 1.4 cm, the average width is 0.5 cm. A small vessel 6 cm high, with a flat bottom 4 cm in diameter, was standing at the feet of the buried. It is ornamented with a cord design composed of six horizontal lines, between which two strips are filled with vertical lines, and one strip with oblique lines. The type of the vessel is typical of the burials of the Caucasian Mineral Waters group (Korenevskiy, 1990: 152, fig. 30; 2018). A grinder made of dark-gray serpentine with a greenish tint was found near the vessel (Fig. 4, 11 ). Its diameter is 6.7 cm on one side, and 8.4 cm on the other side; its thickness is 4.3 cm. The assemblage belongs to the period of the 29th–25th centuries BC, judging by the date (2834–2475 BC) of a similar smooth axe of the Kabardino-Pyatigorsk type from burial 10, kurgan 32 of the Ust-Dzheguta cemetery (4160 ± 60 BP) (Nechitaylo, 1978: 58). It is in good agreement with the date of burial 4, kurgan 3 of the Lysogorsky-6 cemetery.

The third example is burial 1, kurgan 1 of Nezhinsky group I. The burial was performed in the central part of the kurgan. The burial pit, 3.0 × 2.1 m in size, was excavated to the natural ground level. It cut through the fill of the

Fig. 4. Finds from the burials of the Caucasian Mineral Waters group.

1–4 – gold rings; 5 – bronze rivets; 6 – a silver (?) pipe-shaped bead; 7 – a bronze bead; 8 – a bronze nail from the axe socket; 9 – a stone axe; 10 – a bronze dagger; 11 – a stone grinder.

1 , 5–11 – burial 5, kurgan 1 near the wine-making state farm “Mashuk” (after (Afanasiev, 1975)); 2 , 3 – burial 1, kurgan 1 of Nezhinsky group I; 4 – burial 5, kurgan 4 of Nezhinsky group II (after (Korenevskiy, 1988)).

main burial. The pit contained a stone cyst, assembled from slabs, with an internal contour-size of 2.0 × 0.9 m. The cyst was covered by large slabs, with a heap of stones above them. It accommodated the skeleton of a man, who was buried in a flexed supine position, with his head towards the south.

Near the skull and in the chest area, the following items were found: two gold pendants (one-and-half-turn and two-turn ones), with diameters of 10 mm and 8 mm respectively, and with reforged flattened ends (Fig. 4, 2 , 3 ); two forged trapezoidal plaques (with the height of 38 mm and the base of 30 mm), with an opening in the center and a punch ornament in the form of a diagonal cross; three cornelian disk-shaped beads 10 mm in diameter; silver pipes 15 mm long and 3 mm in diameter; three cylindrical paste beads and one round bead; and two animal bones (Korenevskiy,

1988: 9, 10; Gey, Korenevskiy, 1989: 270). This burial can be interpreted as a female, judging by the set of goods, since forged plaques are not encountered in male burials of the Caucasian Mineral Waters group. In other assemblages of the Kuban region (Bolshoy Petropavlovsky cemetery, kurgan 5, burial 3) and steppe Stavropol region (Rasshevatskaya-1, kurgan 14, burial 2), such trapezoidal plaques were accompanied by hammerlike pins—typical ornaments of female burial outfit (Gey, Korenevskiy, 1989; Korenevskiy, 1990: 81, 82; Gak, Kalmykov, 2013: 128, fig. 8, 6 ).

The fourth example is burial 5, kurgan 4 of Nezhinsky group II. A vast burial pit (3.2 m long, about 2.2 m wide) with ledges was let into the mound right in the center of the kurgan, and thus destroyed the ancient main burial. Burial 5 can be regarded as a secondary main burial of the Middle Bronze Age. The skeleton in the pit belonged to a 25–30-year-old man (as identified by G.P. Romanova) buried in an extended supine position, with his head towards the east. Ocher is noted near his feet. Under the skull, a gold ring-pendant 8 mm in diameter, with unclosed ends (Fig. 4, 4 ), was found. A footed incense burner ornamented with concentric circles was standing at his feet (Korenevskiy , 1988: 124, fig. 74, 75, 3 ; 1990: 148, fig. 26, 3 ). Among the pit filling stones, a vessel 14.7 cm high, decorated with rows of slotted (nail) “herringbone” ornament, was found (Korenevskiy, 1988: 125).

Discussion

The above assemblages with gold pendants suggest that such ornaments belonged to people who were buried according to special rules. In two cases, they were headgear details of people buried with the highest honors, with weapons and implements. Once, gold pendants were included in the set of adornments of a woman buried in a very large-scale burial facility in the center of the kurgan. This points to a special significance for burials with gold ornaments with respect to other burials of the Caucasian Mineral Waters group, which are located at the circumference of the site. Another gold pendant was a detail of headgear of a man who was buried with honors, in a big pit with ledges let into the center of the burial mound, which allows us to consider it a “new” main or “dominant” burial in the kurgan.

Noteworthy are also two burials with gold pendants and weapons, namely, burial 4, kurgan 3 at Lysogorsky-6; and burial 5, kurgan 1 near the wine-making state farm “Mashuk”. We shall describe them in more detail. The range of analogies for finds from burial 4, kurgan 3, is extremely peculiar. Apart from the noted cases in the Caucasian Mineral Waters group, a gold ring was found along with a stone axe in burial 1, kurgan 15 at Chegem II

(Betrozov, Nagoev, 1984: 26). In the Southern Caucasus, gold coils are present in a set containing bronze axes of the Gatyn-Kale type (Korenevskiy , 1981: 27, fig. 5, 1 , 2 ), a fluted groove, a dagger, and an awl in kurgan 3 near the Martkopi village (Dzhaparidze, 1998: 42, fig. 25).

A bronze rod in the form of a stick with a maceshaped top is a unique item. A similar, though wooden, rod is available among the finds from burial 1, kurgan 5 of Nezhinsky group II (Fig. 3, 9 ). This burial was a joint one and the youngest among the Caucasian Mineral Waters burials in this kurgan (Korenevskiy, 1986; Korenevskiy, Berezin, Gabuev, 2018).

A bronze beaker is the second unique item in burial 4, kurgan 3 at Lysogorsky-6, since this is the first metal vessel found in the North Caucasian culture burials. Its nearest parallels may be beakers from Trialeti kurgan V (Kuftin, 1941: 417, pl. XCI; Dzhaparidze, 1994: 87, fig. 26, 18 ] and the Karashamb kurgan (Kushnareva, 1994: 100), but only as items belonging to the same category of vessels.

Ornaments of burial outfit in the form of beaded bracelets are typical of the people of the North Caucasian culture. An anklet composed of pin pendants is especially illustrative in this respect. The representatives of the Late Pit-Grave culture in Ciscaucasia also had such adornments (possibly, sew-on patches on legging-type long trousers (Korenevskiy, 1990: 59, 60).

Three abraders show traces of use in everyday life. Similar finds are available in the assemblage from the caster-blacksmith and weapon-smith grave (burial 10, kurgan 3 of the Lebedi cemetery (Gey, 1986: 23, fig. 9). The presence of these artifacts suggests that the man buried in the Lysogorsky-6 cemetery was engaged in metal working, i.e. was a blacksmith.

The tradition of placement of wooden trays with low flanges into graves was noted by V.L. Derzhavin in materials from the Tomuzlovka group burials of the Catacomb culture in the Central Stavropol region. Trays are known from the Manych-type burials in the Lower Don area (Derzhavin, 1991: 97). One of them was recorded in burial 32 of the Ipatovo kurgan, dated to the 23rd to 22nd centuries BC, in the north of the steppe Stavropol region (Korenevskiy, Belinskiy, Kalmykov, 2007: 95; 166, fig. 26, 7) . Derzhavin assumes that the trays performed a special ritual role, since bronze daggers and food were put on them (1991: 97). Judging by the Lysogorsky cemetery, various implements, weapons, and socially prestigious items were placed on the trays. This tradition is not typical of burial rites of the North Caucasian culture of the Central Ciscaucasia. Wooden trays are not encountered in other burials of the Caucasian Mineral Waters group. Their presence in this burial emphasizes its peculiarity.

Especially noteworthy is the combination of an axe as a symbol of weapons, and an adze as a symbol of woodworking tool in burial 4, kurgan 3 of the Lysogorsky-6 cemetery, i.e. the so-called military and production (carpentry) kit. It was well represented in the MNC assemblages of Ciscaucasia. In the 3rd millennium BC, after the tribes belonging to this community disappeared in the Northern Caucasus, such kits became typical for the Early Kurgan Martkopi-Bedeni group burials in Georgia (kurgans 3–5, 9 in Martkopi; kurgan 2 in Tetri-Tskaro; the kurgan on the Bedeni plateau (Dzhaparidze, 1998: Fig. 13, 14, 28, 52; Kushnareva, 1993: 101–103; Gobedzhishvili, 1980: Pl. X)), and one kit was recorded in the northwestern Azerbaijan (a burial in the Gasansu hill) (Museibli, Akhundova, Agalarzade, 2011). Some of the said kurgans were destroyed in ancient times. This makes rather difficult to define the symbolism of burial goods as super-elitist or initial-elitist. However, the most outstanding assemblages include ornaments made of gold and silver, which are indicative of super-elitist funerary practices. Notably, these burials were sometimes constructed using timber cribwork. The Early Kurgan group of the Southern Caucasus belongs to the middle of the 3rd millennium BC (the 28th to 24th centuries BC (Dzhaparidze, 1998: 200), the 26th to 24th centuries BC (Sagona, 2017: 302, fig. 7, 2)). These assemblages contain bronze axes of the Gatyn-Kale and Martkopi–Gatyn-Kale types*.

In Ciscaucasia, kits composed of a bronze Nacherkezevi-type axe and a bronze adze are known in several burials: burial 4, kurgan 3 of the Lysogorsky-6 cemetery (the North Caucasian culture); burial 24 of the Zagli-Barzond cemetery (the Kura-Araxes culture); burial 30, kurgan 1 of the Ordzhonikidze cemetery, near the Bamut village (the Late Pit-Grave culture); and a destroyed burial in the Andreevskaya Valley, near the city of Grozny (Burkov, Rostunov, 2004: Fig. 5). The cultural attributions of these assemblages are different. However, their localization points to the multicultural symbolism of such burial kits formed under the influence of Southern Caucasian types of weapons and tools, and embodied in the traditions of piedmont population of the Central Ciscaucasia. This leads to the conclusion that the military and production (carpentry) symbolism remained in a modernized form during the post-Maikop period (the 3rd millennium BC) among various tribes, including the Early Kurgan Martkopi-Bedeni people and contemporaneous groups of Central Ciscaucasian population that maintained ties with their southern neighbors and borrowed shapes of bronze battle-axes with bronze wedges (of the Nacherkezevi type) from them.

It is also important to note that a bronze adze has never been found in the numerous assemblages with stone axes of the Kabardino-Pyatigorsk type, one of which was found in burial 5, kurgan 1 near the winemaking state farm “Mashuk”. On the other hand, there are several examples of finding stone axes associated with stone grinder-anvils, such as burial 9, kurgan 2 on the Rakitnaya mountain; burial 8, kurgan IV of the Tri Kamnya cemetery; burial 14, kurgan 2 on the Konstantinovskoye plateau; and kurgan 2 near the village of Zayukovo (Kabardino-Balkaria) (Korenevskiy, 2018). These assemblages mirrored another military and production (smithcraft) model of burial symbolism. Such a tradition of burying blacksmiths-casters took place, in its different variants, in a wide range of Eastern European tribes. First of all, it emerged among the PitGrave culture people in the Lower Dnieper region, as early as the 4th millennium BC. Subsequently, this tradition can be traced as an pan-cultural phenomenon in the materials from the sites of the 3rd millennium BC and later—the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age in Eastern Europe, Northern Pontic Region, and Ciscaucasia (Ibid.).

Special attention should be given to the deer antlers and the two crania of bulls in the heap of stones above burial 4, kurgan 3 at Lysogorsky-6. The bull cult was very widespread in the primal religions. Right now, we are interested in its reflection in burial rites belonging to the cultures of the 4th to 3rd millennia BC. Analogs include the assemblage with two crania of bulls in burial 25, kurgan 1 of the Maryinskaya-5 cemetery, pertaining to the Dolinsk MNC variant of the Late Uruk period; the burial date is 3334–3097 BC (Kantorovich, Maslov, Petrenko, 2013: 89, fig. 42; p. 92). The heads of bulls were offered as a sacrifice in the burials of nobility of the Alaca Höyük cemetery (tombs E, F, K, L), dating to the middle of the 3rd millennium BC (EDIII) (Kosay, 1951: 164–168, pl. CLVIII, CLXVIII, CLXXXIX). The above examples are associated with the societies that had a military elite, and practiced a super-elitist rite of burying the war leaders, who were also related to cult functions. In this list of analogies, we should note the obvious contemporaneity of the tradition of offering sacrifices in the form of heads of bulls, and even the chronological priority of Ciscaucasia as compared to the areas further to the south, where burials of the highest leaders, who were in addition endowed with symbols of social and cultic power, were performed.

The presence of weapons and implements in the assemblages under consideration allows us to assign the tribes that left burial 4, kurgan 3 of the Lysogorsky-6 cemetery, and burial 5, kurgan 1 of the cemetery near the wine-making state farm “Mashuk” to the same prepolitarian stage of the early period of pre-state development as the MNC, though to a different model. They adhered only to the initial-elitist symbolism, using ornaments made of precious metals. Other burials with weapons (stone axes, maces) of the Caucasian Mineral Waters group are characterized by the militaryegalitarian symbolism: according to the accepted funerary practices and mythology of the otherworld’s structure, weapons were not accompanied by items made of gold or silver at all.

Headgear ornamentation with gold and silver rings was a widespread feature of social ranking, and distinguished the nobility in many cultural formations of the Middle Bronze Age in Ciscaucasia. For instance, gold pendants in the 3rd millennium BC are encountered in burials of the Early Catacomb and Late Pit-Grave cultures in the steppe Stavropol region and Kalmykia (sites in the Yegorlyk-Kalaus interfluve) (Gak, Kalmykov, 2013). These finds in the assemblages are not related to weapons. Meanwhile, ring-pendants, though made of silver rather than of gold, can be found in military burials with bronze axes in Ciscaucasia and in the Southern Caucasus (for example, burial 6, kurgan 2 of the Bichkin Buluk cemetery, burial 30, kurgan 1 of the Ordzhonikidze cemetery, burial 2 at Nacherkezevi). Such a special feature of the ritual outfit was, probably, caused by the canons of funerary practices aimed at emphasizing the personal prestige (a rank, clan, or status) of an individual, and not at demonstration of his/her material prosperity, since, in other respects, goods in these burials had no significant differences from graves without items of precious metals.

Conclusions

The observations conducted in Ciscaucasia suggest that the gold rings of headgear in the Caucasian Mineral Waters assemblages mark the burials of nobility, both men and women, whose status was sufficiently high to consider them representatives of a local group. Their graves could have been related to the construction of a new kurgan or were special joint burials. Such an attitude towards burials of the local elite can be regarded as a special feature of the tradition of ranking the tribal nobility belonging to the Caucasian Mineral Waters group, where the warrior stratum was gaining the leading position.

A specific trait of burial 4, kurgan 3 at Lysogorsky-6 and burial 5, kurgan 1 near the wine-making state farm “Mashuk” with gold pendants and stone axes was their placement almost in topsoil, and not in a deep bedrock layer. Possibly, this implied connection of the rites with the fertility cult. The western orientation of the deceased in these burials is also unusual, since in the Caucasian Mineral Waters group kurgans of the Middle Bronze Age, buried people are often oriented with their heads towards the east (burial 14, kurgan 1; burial 2, kurgan 4; and burial 6, kurgan 3 of Nezhinsky group I (Korenevskiy, 1988: 22–26). Obviously, these two persons of high rank

(possibly, chieftains) were buried in such a way that their path to the realm of ancestors and their place in it differed from those of other honored tribesmen. Many ancient tribes on various continents had such mythological ideas of various places for the abode of the souls of the dead. For example, the Aztecs believed that souls of heroes go to the sun, while others (not warriors) are dispatched to the underworld. According to the beliefs of the Caribs, brave people after their death will live on the Islands of Happiness, while other tribesmen are consigned to desert lands beyond the mountains (Davie, 2003; Korenevskiy, 2017: 122–124). These ideas of different places for kinsmen’s stays in the other world, according to their status and rank in this world, reflected an epoch during which military tension was increasing, efficient stone and metal weapons were created, and hierarchical structures were evolving in societies. Chieftains and weaponsmiths occupied special places among their tribesmen, and gold was considered a more prestigious metal than silver and copper.