China-US strategic competition in the Lower Mekong region and Vietnam’s position

Автор: Tran N.D.

Журнал: Вестник Новосибирского государственного университета. Серия: История, филология @historyphilology

Рубрика: Геополитика Юго-Восточной Азии

Статья в выпуске: 10 т.22, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Recently, both China and the United States of America (US) have started focusing more on settling influence in the Lower Mekong region in the general context of global China-US competition. Although they have different connecting approaches, both superpowers focus on establishing and maintaining their influence in the strategic geo-political area in Southeast Asia and Asia. Their activities in the Lower Mekong region are more noticeable since the 2010s when Xi Jinping came to power in China and the US conducted the “Pivot to Asia” and “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” policies. Their competition therefore raises difficult tasks for Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam (CLMTV) to keep neutrality, and protect their national sovereignty and the regional sustainable development. As the China-US competition in the Lower Mekong region is remarkable and profoundly influential to the development of regional countries, both academic scholars and policy makers pay attention to this subject. This paper focuses on evaluating the recent competition between China and the US in CLMTV and Vietnam’s adaptations to maintain its sovereignty, security and neutrality in the great-power competition, especially since Vietnam established a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with both China (2008) and the US (2023).

The lower mekong region, china-us competition, regional influence, vietnam’s diplomacy

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147242416

IDR: 147242416 | УДК: 94 | DOI: 10.25205/1818-7919-2023-22-10-122-131

Текст научной статьи China-US strategic competition in the Lower Mekong region and Vietnam’s position

The Lower Mekong region comprises Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam (CLMTV). This region has played an increasingly important role in Southeast Asia; a competitive area for many powers since the end of the 20th century. The strategic competition between China and the US is increasing, especially after Xi Jinping changed China’s neighbourhood policy and the US proposed the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP). Both of them are seeking to expand their influence in the Indo-Pacific region and CLMTV is one of the key points for competition. Their competition in the Lower Mekong creates both advantages and difficulties for regional countries. This subject has therefore drawn much attention from international scholars and policy makers with various perspectives. This article summarizes the process that the two superpowers have recently undergone to create influence and compete in CLMTV and its impacts on regional countries by viewing both their primary plans and previous research about this subject. Beyond that, this paper views Vietnam’s policy and responses to the China-US competition there to maintain neutrality, sovereignty and opportunities to exploit both the US and China’s sources to develop. Interestingly, Vietnam created a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with both China and the US to cooperate with both superpowers and to avoid depending on any one country in the great-power competition.

Expansion of China’s influence in the Lower Mekong region

China tried to create influence on CLMTV from the 1990s by involving in and cooperating with the Mekong River Commission (MRC) and the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS). China wanted to affirm its role in both politics and diplomacy there, while taking advantage of CLMTV's natural and labour resources to develop the Chinese domestic economy [Nguyen, Nguyen, 2018, p. 98– 100]. Unlike the US with its ideas about democracy, human rights, good governance, and the rule of law in creating a relation with CLMTV, China applied advanced pragmatism-oriented diplomacy via both bilateral relations and multilateral forums [Hidetaka, 2015, p. 176].

China's investment in and influence on CLMTV in the early 21st century was more prominent than that of the US. China paid 7.2 billion USD for the railway project connecting Vientiane with China and a non-refundable investment of 30 million USD to help Laos to build a highway [Lim, 2008, p. 41; Truong, 2014, p. 163]. China provided 27.2 % of the capital for the GMS (1994–2007), which was increased to 32.2 % (2008–2012). In comparison, the US had almost no commensurate investment and cooperation in CLMTV during that period [Menon, Melendez, 2011, p. 22]. Trade with China increased from 6.3 % of CLMTV’s exportation in 2000 to 14 % in 2009 [Srivastava,

Kumar, 2012, p. 20]. Through its economic cooperation, China partly exerted political influence there. For example, in 2011 while most Southeast Asian countries expressed concern about the security in the South China Sea, Cambodia and Myanmar did not share the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) concerns. In 2012, when Vietnam and the Philippines wanted China to respect their economic sovereignty in the South China Sea, Cambodia thought that this could strain relations with China.

Between 2010 and 2020, China's influence in CLMTV enormously improved. The three issues affecting China's policy in CLMTV were: 1) the impact of tariffs, 2) pressure from non-traditional issues, 3) China's ambition for a more comprehensive role as a superpower that could decide major regional and international issues [Guangsheng, 2016, p. 4–6]. Beijing considered CLMTV as a “new front for China-US rivalry in Southeast Asia” 1 and therefore, China’s diplomacy there was more urgent. The founding of Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) in 2016 was a typical example of China's increasing influence there. The LMC conducted 78 infrastructure projects with 5 top priority issues: production capacity, cross-border economic cooperation, water resource management, poverty reduction and connectivity [Brilingaite, 2017, p. 15–16]. The LMC aimed to solve problems such as China’s role in the MRC or the GMS’ lack of political and social elements [Guangsheng, 2016, p. 4–5]. The LMC provided China with two advantages in controlling and influencing CLMTV: 1) a way to exchange and directly connect CLMTV with China's development and security, 2) bringing CLMTV into China's chain of influence through various initiatives.

China created substantial economic influence in CLMTV through a “full spectrum of two-way trade, multi-modal connectivity, tourism, investment, development aid and infrastructure financing” [Hoang, 2023, p. 11]. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, China-CLMTV trade reached 416.7 billion USD in 2022, around 5 % higher than that in 2021 2. More specifically, China-Cambodia trade obtained 11.1 billion USD in 2021, and 11.64 billion USD in 2022. China became Cambodia’s biggest export in 2022 [Vannarith, 2023, p. 3]. Although the US is Thailand’s great friend, China is its number-one partner of economic benefit as the two-way trade increased from 82 billion USD (2020), to 107.3 billion USD (2021). From 1995 to 2021, Thailand’s exportations to China increased 20.7 times 3. Laos-China trade was not as noticeable as that of other countries but it increased to 4.15 billion USD in 2021, and since 1989 to the present, China has around 815 projects in Laos valued at 16 billion USD [Lin, 2023, p. 9]. China also played a key role in investing in Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar [The ASEAN Secretariat, 2022, p. 14–15], which could help China to obtain more power in those countries.

China built hydroelectric dams on the Mekong River to manage water and control other problems of CLMTV [Middleton, Allouche, 2016, p. 107]. China considered its sovereignty and jurisdiction over regional water resources and it has approached several ways to control water security in the region [Hoang, 2022, p. 3–4]. China considers water as a resource of Chinese soft power, and Beijing exploited the LMC as Sino-centric multilateralism to control regional water security, to raise its influence in the Lower Mekong. A total of 11 Chinese mainstream dams and 95 tributary dams have seriously affected the water resources, environment, and economy of CLMTV. In 2019 and 2020, rice production of Vietnam and Thailand seriously decreased due to lack of water and alluvium. It is predicted that by 2042, CLMTV will lose about 16 billion USD in the fisheries industry as a result of China's dams.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, China also tried to create more influence on CLMTV using soft power. Beside the “mask diplomacy”, at the 3rd LMC summit in 2020, China pledged to share vaccines and medical experts with CLMTV, making it an important and potential political tool to enhance Chinese power there. CLMTV is believed to be one of the most vulnerable regions due to the COVID-19 pandemic and apart from Vietnam, other regional countries were receptive to China’s COVID-19 diplomacy [Vannarith, 2021, p. 3–4].

Competitive activities of the US in the Lower Mekong region

The US was later than China in creating influence in the Lower Mekong, and tried to put this region in the context of Chinese-US competition and its “Pivot to Asia” in response to China's influence expansion. In 2009, the US and Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam (Myanmar joined in 2012) agreed to cooperate in the Lower Mekong Initiative (LMI) with four basic pillars: environment, health, education and infrastructure development. The US also built Friends of the Lower Mekong (FLM) to enhance its influence in the region by improving aid coordination, information sharing, and policy quality and effectiveness. Ministerial meetings between the US, CLMTV, Australia, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, and representatives of the European Union, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank (WB) were first held in July 2011.

Support of the US for CLMTV focuses on challenges in the transboundary environment and on sustainable development. The US aimed to develop Mekong standards based on cooperation in science, technology and environment. However, the actual US presence in CLMTV in the early 2010s remained unclear, even rather weak. It did not provide any development financial assistance for CLMTV under the ASEAN-Mekong Basin Development Cooperation (AMBDC) program. The US' direct investment in Laos and Cambodia was small and insignificant while investment in Vietnam was reduced from 3.3 billion USD (2009) to 52 million USD (2013). Washington primarily focused on highlighting the negatives of China's expansion policy without taking a multi-dimensional perspective for a more appropriate approach. Moreover, the US neglected ASEAN’s role in dealing with CLMTV as the LMI did not invite ASEAN representatives to attend its meetings and did not accompany ASEAN's programs on the Mekong. Accordingly, the US could not erase the gap with CLMTV in this period.

Under President D. Trump, the US policy towards CLMTV changed and the China-US competition was more intensive. In 2018, the US Secretary of State, M. Pompeo reaffirmed that the LMI was key to promoting regional connectivity, economic cooperation, sustainable development and government stability 4. The US pledged 45 million USD to support the LMI projects to improve living quality and sustainable environment. M. Pompeo stressed that the US was ready to protect CLMTV’s sovereignty and security 5. From 2009 to 2020, the US provided nearly 3.5 billion USD to support CLMTV. They included, in USD: 1.2 billion for health programs, 734 million for economic development, 616 million for peace and security, 527 million for human rights and governance, 175 million for education and social services, and 165 million for humanitarian assistance 6.

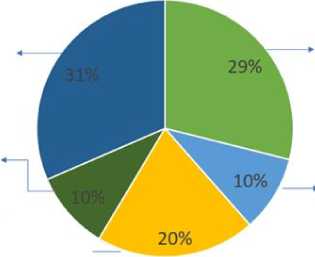

In 2020, the US upgraded the LMI to the Mekong-US Partnership Initiative (MUSP), with the goals of upgrading connectivity, perfecting government and fundamental development in CLMTV, and demonstrating Washington’s strategic competition with China there (fig. 1). The US and CLMTV expanded cooperation in economy, energy security, development and quality of life, transboundary water and resource management, and non-traditional security issues. Washington announced to guarantee at least 153 million USD for CLMTV in direct cooperation projects 7. The US

intended to provide 52 million USD to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic in the region. Washington also provided a series of policy advisory forums to support policy makers and local communities for regional development 8.

Cambodia $103m *"

Laos

S49m

Vietnam

S161m

Myanmar S148m

Thailand $5 Im

■ Myanmar ■ Laos Cambodia ■ Thailand ■ Vietnam

Fig. 1 . US Foreign aid to the Lower Mekong countries. As per: [Eyler, 2020, p. 16]

Рис. 1. Помощь США странам Нижнего Меконга. По: [Eyler, 2020, p. 16]

Unlike Trump’s government which chose to neglect ASEAN’s role in enhancing relations with CLMTV, the US’s policy under President J. Biden focuses more on ASEAN’s contribution. Washington wanted to cooperate with ASEAN for “its efforts to deliver sustainable solutions to the region’s most pressing challenges” [The White House, 2022, p. 9]. The US upgraded its relationship with ASEAN to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, and exploited ASEAN’s mechanism and tools to engage deeply in CLMTV. In the ASEAN-US Special Summit 2022, the US mentioned its attempts to promote the “stability, peace, prosperity, and sustainable development of the Mekong sub-region” via MUSP and under other plans of the US with ASEAN with the goal of securing a “win-win” situation and of competing with China there 9. However, Biden did not show any “pronounced interest in participating in any multilateral economic agreements” with CLMTV, and therefore the US could lose its position there [Stepanov, 2022, p. 1477]. The US launched a 2021–2023 MUSP plan to deal with four primary issues of economic connectivity, sustainable development, non-transitional security and human resource development 10. Interestingly, Biden introduced the term “free and open Mekong” 11 to seek to “advance freedom and openness and offer autonomy and options” for the region [Hoang, 2023, p. 5].

The US attempted to raise its economic influence in CLMTV by both trade and investment. Trade between the US and CLMTV in 2018 reached 109 billion USD [Chu, 2020, p. 4], and nearly 117 billion USD in 2019 [Bui, 2021, p. 100–101]. CLMTV's exports to the US increased gradually and noticeably, in which Vietnam and Thailand were the two most important partners. In the period 2011–2018, Vietnam's exports to the US increased nearly three times, from 20 billion USD to 50.5 billion USD, and Thailand's raised from 27 billion USD to 36.2 billion USD. Vietnam became the 17th largest trading partner of the US, and Thailand ranked the 20th [Eyler, 2020, p. 7]. In 2021, nearly 1,000 US private companies operated in CLMTV, of which 612 were in Thailand, 312 in Vietnam, 38 in Cambodia, 21 in Myanmar and 10 in Laos [East-West Center, 2021, p. 26]. Noticeably, although recent US investment in ASEAN is higher than that of China, the US paid more attention to Singapore and its investment to CLMTV was less than China’s while China was the most important source of investment for Thailand, Cambodia and Laos [The ASEAN Secretariat, 2022, p. 9]. That situation, together with the fact that only Vietnam and Thailand joined the US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) while both China and CLMTV were members of the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area (ACFTA) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) caused the US disadvantages to compete with China’s influence in CLMTV.

Vietnam in the strategic China-US competition

Besides cooperation opportunities, there are more and more risks for CLMTV in maintaining bilateral and multilateral relations with both China and the US. Cooperation with any great power should be cautious because it is easy to cause conflicts with one another, even with the rest of Mekong’s countries and ASEAN. Three problems for CLMTV in the context of China-US strategic competition are: 1) the difference in CLMTV’s interests in multilateral cooperation, 2) their unique opportunities and challenges in handling relations with their partners, 3) difficulty and complexity in regional water security cooperation [Le, 2020, p. 103]. Vietnam and other countries in the Lower Mekong need to deal with the China-US competition, balance and calculate how to cooperate effectively, and avoid confrontation and upholding engagement. Although the China-US competition has not yet reached the level to force CLMTV to “choose a side”, they need to have a strategy to maintain their neutrality, to unite and send an apparent message that strengthening cooperation with external powers cannot be equated with choosing sides.

Sharing the same border, China had many advantages of creating influence on Vietnam [Guili-yev, 2022]. Bilateral relations have significantly improved from strategic antagonism to ideology-shared partnership and comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership with “16 words” 12 and the spirit of the “4 good” 13. Despite Vietnam’s concerns regarding China’s expansion and territorial claims in the South China Sea, bilateral political and economic relations were promoted. After the 20th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, the General Secretary of the Vietnamese Communist Party, Nguyen Phu Trong made a formal visit to China to enhance bilateral relations. During that visit, Vietnam and China agreed to encourage the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties (DOC) effectively, to attempt to complete the Code of Conduct (COC) to maintain peace and stability in the South China Sea.

Vietnam-China trade jumped sharply after the China-US trade war [Fatharani, 2022, p. 720– 730]. In 2021, Vietnam's exports to China maintained the 2nd place after the US, reaching 55.9 billion USD (28.6 % of total export value). In return, China was Vietnam's largest import market with a value of 110.5 billion USD (33.2 % of total import value). Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the import value still increased by 31.3 % compared to 2020 [General Statistics Office, 2022, p. 610]. Since 2004, China has always been Vietnam's largest trading partner, and since 2020, Vietnam has been China's 6th largest trading partner. China’s investment in Vietnam also raised quickly. Until May 2022, China was the 6th largest investor of Vietnam with 3,390 projects valued at 22.186 billion USD.

Washington believes that the US can compete with China in the Lower Mekong via bilateral relations with regional countries, especially Vietnam or Thailand. Via the IPEF, the US wanted to use multilateral tools to have influence in Vietnam as IPEF “places a strong emphasis on close collaboration with the private sector”, and creates good “opportunity for companies in the region to shape and influence policy decisions and direction” [Gunasekara-Rockwell, 2023, p. 36]. The US-Vietnam trade in 2021 and 2022 exceeded 138 billion USD [Nguyen, 2023, p. 16–17]. In March 2023, a mission of 52 US companies under the US-ASEAN Business Council visited Vietnam to find investment opportunities. In July 2023, the US Treasury Secretary J. Yellen visited Vietnam for further promotion of economic ties and post-pandemic recovery. She affirmed that the US considers Vietnam a key partner in advancing a free and open Indo-Pacific and wants to upgrade US-Vietnam relations on the 10th anniversary of their comprehensive partnership.

Vietnam is also ready to collaborate with the US to enhance their bilateral relations further and encourage regional peace, stability, cooperation and development. Vietnam expects that the US would become its largest investor in the future, and appreciates the US’ role in improving Vietnam’s economy and international position 14. Especially, on 10/9/2023, Vietnam and the US announced the establishment of a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) and the US became Vietnam’s 5th CSP (China was the first in 2008). As such, Vietnam wants to exploit both China and the US for its sustainable development. However, Vietnam does not want to be in the middle of the ongoing strategic China-US competition which could negatively affect Vietnam’s economic and political improvement.

Vietnam considers the Mekong region as its direct security zone which plays an increasingly key role in maintaining and promoting international peace, stability and prosperity. Vietnam has always cooperated positively with great powers and regional countries for sustainable development. The 13th Congress of the Vietnamese Communist Party confirmed that Vietnam consistently exercise the foreign policy of independence, autonomy, peace, friendship, cooperation, development, diversification and multilateralization with the “Four Nos” principle 15 to protect national interests respecting international law [Communist Party of Vietnam, 2021, p. 143, 146]. Vietnam applies a “bamboo diplomacy” 16, attempting to maintain neutrality without choosing a side in the China-US competition. The 13th Congress stressed that Vietnam must build a stable partnership with all major powers, especially China and the US 17. A clear message was sent to both superpowers that Vietnam wants to cooperate with them in positive ways to benefit all; to secure and promote regional peace, security, and prosperity.

In brief, both China and the US pay more attention to Vietnam and this fact requires Vietnam to have suitable diplomacy to keep its sovereignty and neutrality. Considering and choosing an appropriate policy in the tense China-US relationship is always a careful and complicated problem for Vietnam. China is Vietnam’s neighbouring power, has traditional relations, and is a strategic partner. However, Vietnam also needs the US to develop its economy and society and partly limit its dependence on China. Balancing this relation and building connections with other powers is a way for Vietnam to exploit great powers’ investment, science and technology to serve the national goal of industrialization and modernization [Grossman, 2020, p. 24–65]. Vietnam recognises that ASEAN and its mechanisms can play a significant role in settling and maintaining regional security and provide platforms for Vietnam to maintain political neutrality in the great-power competition.

In the future, Vietnam can play more of a role in improving regional cooperation and keeping neutrality in the China-US competition. Firstly, Vietnam can focus more on building a comprehensive strategy about Mekong to show Vietnam’s aims, priorities, and collaborative approaches. From that strategy, Vietnam can build inter- and intra-regional cooperative mechanisms to protect security, sovereignty, sustainable development and to promote regional economic connectivity. Secondly, Vietnam can exploit and expand more of a role of multilateralism such as ASEAN, GMS, MRC and others, to deal with CLMTV’s issues. The involvement of international organisations in this region provides more effective approaches for Vietnam to protect peace, stability, water security and to encourage economic development. In which, ASEAN’s involvement in all issues of CLMTV is necessary and significant, not peripheral, in order to deal with the China-US geopolitical competition. Thirdly, Vietnam can effectively involve a multilateral mechanism led by China and the US to balance the power and influence of the two superpowers. Both China and the US are the most significant trading partners of Vietnam, and promoting economic cooperation with these two superpowers are one of the key targets for Vietnam’s development and autonomy. Fourthly, Vietnam can expand the role of bilateral and multilateral diplomacies with both regional and international countries to promote peace and stability of the Lower Mekong region. Via international conferences, forums and cooperation, Vietnam can learn more innovations and advice to protect its sovereignty in the China-US competition. Fifthly, improving relations with other powers such as Russia, Australia, India, Japan and Korea is an effective way to enhance Vietnam’s potential and ability to protect its autonomy.

Conclusion

Together with other powers, both the US and China focus more on strategic competition in the Lower Mekong in a broader context of the Indo-Pacific region. Although the US attempts to promote regional government cooperation for sustainable development, China has its own advantages with increasing economic exchange and investment. Both superpowers exploited their initiatives such as LMC or MUSP to deeply engage in CLMTV. As Biden’s National Security Strategy considered China as a “potential competitor” and the great-power competition is increasingly apparent in recent years, the China-US competition in CLMTV will be more tense in the future. China's ambition to control this region to serve a broader plan of southward expansion and the US' attempts to obtain more influence there obviously create their strategic competition.

In order to maintain peace, stability, autonomy and sovereignty, Vietnam needs suitable policies. Both China and the US are important for Vietnam in both political and economic fields. Therefore, choosing a neutral position is the best approach to exploit their investment and cooperation for sustainable development. Vietnam’s bamboo diplomacy is effective in order to keep and promote bilateral relations with both superpowers. As both China and the US are in a comprehensive strategic partnership with Vietnam, Hanoi can exploit their resources for Vietnam’s development, and Hanoi always chooses to cooperate with both superpowers in economy, diplomacy, society to maintain the balance in the region and to obtain the aims of a “win-win” situation. Moreover, indigenous institutions such as ASEAN can provide Vietnam with influential friends to preserve its autonomy and sovereignty in the China-US strategic competition.

Список литературы China-US strategic competition in the Lower Mekong region and Vietnam’s position

- Brilingaite V. China’s transboundary river governance: the case of the Lancang-Mekong River. Master’s Programme in Asian Studies, Lund Uni., Lund, 2017, 41 p.

- Bui T. T. Quan hệ đối tác Mê Công - Mỹ: nền tảng và hướng phát triển đối với tiểu vùng sông Mê Công [The Mekong-US cooperated relation: foundation and new development trends towards the Lower Mekong region]. Tạp chí cộng sản [Communist Review], 2021, vol. 960, pp. 100- 105. (in Viet.)

- Communist Party of Vietnam. Documents of the 13th Party Congress. Hanoi, National Political Publ., 2021, 355 p.

- Chu M. T. Role of the US Lower Mekong Initiative in the Mekong region. Perth US Asia Centre, Indo-Pacific Analysis Briefs, 2020, vol. 10, pp. 1-8.

- East-West Center. ASEAN matters for America, America matters for the ASEAN. Washington, 2021, 41 p.

- Eyler B., et all. The Mekong matters for America, America matters for the Mekong. Stimson, East- West center, 2020, 41 p.

- Fatharani F. Analysis of Vietnam’s response to the US-China trade war in times of pandemic. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Innovation on Humanities, Education, and Social Sciences, 2022, pp. 720-730.

- General Statistics Office [Tổng cục thống kê]. Statistical Yearbook of Vietnam 2021 [Niên giám thống kê Việt Nam 2021]. Hanoi, NXB Thống kê [Statistical Publishing House], 2022, 1058 p. (in Eng. & Viet.).

- Grossman D. Regional Responses to US - China competition in the Indo - Pacific: Vietnam. California, RAND Corporation, 2020, 118 p.

- Guangsheng L. China seeks to improve Mekong sub-regional cooperation: causes and policies. Nanyang Technological University, Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Policy report, 2016, pp. 1-16.

- Gunasekara-Rockwell A. Friendship in the shadow of the Dragon: the challenge of upgrading USVietnam ties amid tensions with China. The journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, 2023, vol. 6, pp. 24-41.

- Guiliyev V. A historical overview of China’s influence on Vietnam. Special report of Topchubashov Center, 2022, pp. 1-28.

- Hoang T. H. China’s hydro-politics through the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation. Singapore, IseasYusof Ishak Institute analyse current events, 2022, no. 116, pp. 1-14.

- Hoang T. H. Is the US a serious competitor to China in the Lower Mekong?. Singapore, IseasYusof Ishak Institute analyse current events, 2023, no. 37, pp. 1-16.

- Hidetaka Y. The United States, China, and Geopolitics in the Mekong region. Asian Affairs: An American Review, 2015, vol. 42, pp. 173-194. https://doi.org/10.1080/00927678.2015.1106757

- Le T. K. Sự gia tăng ảnh hưởng của một số nước lớn tại tiểu vùng Mê Công thông qua các cơ chế hợp tác đa phương và một số đề xuất cho Việt Nam [The influence increase of great countries in the Mekong sub-region through multilateral cooperation mechanisms and implications for Vietnam]. Tạp chí cộng sản [Communist Review], 2020, vol. 933, pp. 95-105 (in Viet.)

- Lim T. S. China’s active role in the Greater Mekong Sub-region: a win-win outcome?. EAI Background Brief, 2008, no. 397, pp. 1-19.

- Lin J. Changing Perceptions in Laos towards China. Singapore, Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute analyse current events, 2023, no. 56, pp. 1-14.

- Menon J., Melendez A. C. Trade and Investment in the greater Mekong Subregion: Remaining challenges and the Unfinished Policy Agenda. ADB working paper series on regional economic integration, 2011, no. 78, 56 p.

- Middleton C., Allouche J. Watershed or Powershed? Critical Hydro-politics, China and the ‘Langcang-Mekong Cooperation Framework’. The International Spectator, 2016, vol. 51, pp. 100-117. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2016.1209385

- Nguyen T. Q., Nguyen T. P. A. Chính sách của Trung Quốc đối với tiểu vùng sông Mê Kông mở rộng hiện nay [Chinese policies towards the Lower Mekong region in recent years]. Tạp chí Lý luận chính trị [Political Theory], 2018, vol. 10, pp. 97-103 (in Viet.)

- Nguyen H. US-Vietnam trade ties: Challenge Ahead. Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, 2023, vol. 6, pp. 15-23. https://doi.org/lnkd.in/e_2FzQd2 Srivastava P., Kumar U. Trade and trade facilitation in the Greater Mekong Subregion. Philippines, ADB & Australian AID, 2012, 170 p.

- Stepanov A. S. US Policy towards Southeast Asia: from Barack Obama to Joe Biden. Herald of the Russian Academy of Science, 2022, vol. 92, pp. 1473-1478. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1019331 622210183

- The ASEAN Secretariat. ASEAN Investment Report 2022: Pandemic Recovery and Investment Facilitation. Jakarta, 2022, 266 p.

- The White House. Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States. Washington, 2022, 19 p.

- Truong M. V. Between system maker and privileges taker: the role of China in the greater Mekong sub-region. Revista Brasileira de Politica Internacional, 2014, no. 57, pp. 157-173. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7329201400210.

- Vannarith C. Fighting Covid-19: China’s soft power opportunities in mainland Southeast Asia. Singapore, Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute analyse current events. 2021, no. 66, pp. 1-10.

- Vannarith C. Cambodia-China Free Trade Agreement: A Cambodian Perspective. Singapore, Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute analyse current events. 2023, no. 46, pp. 1-10.