Colon and rectal cancer are different tumor entities according to epidemiology, carcinogenesis, molecularand tumor biology, primary and secondary prevention: preclinical evidence

Автор: Jafarov S., Link K.H.

Журнал: Сибирский онкологический журнал @siboncoj

Рубрика: Обзоры

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.17, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Introduction. Colon and rectal cancer (CC, RC) are different entities from a clinical and tumor biological point of view. Up to now, both, CC and RC, are synonymously called “Colorectal Cancer” (CRC). With our experience in basic and clinical research and routine work in this field we now have come to the opinion, that the term “CRC” should definitely be questioned, and if justified, be abandoned. materials/methods. We analyzed the actual available data from the literature and our own results from the Ulm based study group FOgT to proof or reject our hypothesis. results. The following evident differences were recognized: Anatomically, the risk to develop RC is 4× higher than for CC. Molecular changes in carcinogenesis in CC are different from RC. Physical activity helps to prevent CC, not RC. Pathologically there are differences between RC and CC. In addition, there are also major clinical differences between CC and RC, such as in surgical topography and- procedures, multimodal treatment (MMT) approaches (RC in MMT is less sensitive to chemotherapy than CC), and prognostic factors for the spontaneous course and for success of MMT (e.g. TS or DPD). discussion. CC´sand RC´s definitely are different in parameters of causal and formal carcinogenesis, effectivity of primary prevention by physical activity, conventional and molecular pathology.According to our findings we can demand from the preclinical point of view that CC and RC are two different tumor entities in terms of various representative biological characteristics.CC and RC are also differing substantially in many clinical features, as outlined in a separate paper from our group. Conclusion. “CRC” should no longer be used in basic and clinical research and other fields of cancer classification as a single disease entity. CC is not the same as RC. CC might even be divided into right and left CC.

Colorectal cancer, rectal cancer, molecular markers, epidemiology, prevention, preclinical trials

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140254205

IDR: 140254205 | УДК: 616.351+616.345]-036.22-084:577.22 | DOI: 10.21294/1814-4861-2018-17-4-88-98

Текст обзорной статьи Colon and rectal cancer are different tumor entities according to epidemiology, carcinogenesis, molecularand tumor biology, primary and secondary prevention: preclinical evidence

Colon- and rectal cancer (CC and RC) up to now are regarded as a single tumor entity, “Colorectal Cancer”/CRC, in all fields of basic- and clinical research as well as in clinical practice. This is based on the assumption that CC and RC develop in the large bowel, thought to be a similar organ from the ileocecal valve up to the dentate line as boundaries to the small bowel on the oral edge and to the anal canal, sphincter ani, and skin, aborally. The term “CRC” has been based on the similar anatomical structure (Mucosa, muscular layer, serosa +/-), function (stool concentration, fluid resorption, stool transportation and excretion) of the organ, and histology of CC and RC. Our groups for decades have worked on colon- and rectal cancer in basic-, translational-, and clinical research projects. We also have been involved in national projects to structure and improve treatment of colon- and rectal cancer patients (Interdisciplinary Ulm-based “Forschungsgruppe Oncologie Gastrointestinale Tumoren” (FOGT); German Cancer Society (DKG) -S3 Guide lines, DKG structural commision for DKG Large Bowel Centers, Surgical Group for Visceral Oncology (CAO-V)) and organized in part nationwide activities/projects for disease prevention for the Hessian and German Cancer Societies (HKG, DKG): (“1000 Mutige Männer” (a project to motivate for preventive colonoscopy), and “du bist kostbar”(nationwide DKG-projects for cancer prevention and living with cancer (www. ). With those activities, and the associated knowledge and experience we came to the conclusion that summarizing CC and RC to “CRC” must be questioned. Therefore, we analyzed the literature to landmark characteristics of CC and RC, such as epidemiology, carcinogenesis, prevention, clinical symptoms, diagnosis, multimodal therapy and clinical results to find out, whether there are significant homogeneities between CC and RC justifying the definition “CRC” or rejecting it. Our experience and the results of two large multimodal treatment studies, FOGT 1 (adjuvant chemotherapy of colon cancer) and FOGT 2 (adjuvant radiochemotherapy of rectal cancer) were included in the analytic set up at highest evidence levels. Rejection of the term “CRC” would divide CC and RC as self standing tumor entities. Recent publications concerning the molecular biology of these tumors support this hypothesis. In this paper we present the preclinical differences between CC and RC.

Materials and Methods

For recapitulating the basic known information we described the current anatomical/topographical definitions of the colon and the rectum, the macro- and histopathology of colon and rectal cancers in standard literature/books/actual S3 guide lines on “colorectal cancer”. Then we analyzed actual reports (papers and abstracts)in English language on the epidemiology, etiology, formal and molecular carcinogenesis, hereditary syndromes, preventive possibilities, clinical symptoms, diagnostic procedures, surgical procedures, multimodal therapies, follow up, and short term results/long term results. We analyzed more than 2000 publications available from Pubmed, Medline etc. concerning these fields between 2000-2018 using the keywords “colorectal cancer”, “colon cancer”, “rectal cancer”, “chemosensitivity of colon and rectal cancer”, “chemotherapy”, “surgery”, “radiochemotherapy”, “randomized clinical trials”, “molecular biology”, “prognostic factors”, and others. We also took informations from the German S3 Guide Lines “Colorectal Cancer” from the versions 2008 and 2013. Results from the data bases from the FOGT trials on improvement of multimodal adjuvant chemotherapy in CC (FOGT1) and adjuvant radiochemotherapy in RC (FOGT2) and associated publications [1, 2] were used to substantiate or reject our hypothesis. The results concerning the preclinical informations are presented.

Results

Anatomically/topographically the rectum is defined as large bowel up to the edge of 16 cm from the anocutaneous line. The lower third reaches up to <6 cm, the middle third from 6-12 cm, and the upper third from >12-16 cm. The upper third has an intraperitoneal position, while the two lower two thirds are located extraperitoneally in the small pelvis. The upper edge of the rectum may also be defined by the confluens of the three colon tenias to a single rectal tenia. The topography of the upper third is varying between males and females. The two lower thirds have a sophisticated topography concerning the mesorectal structures, fascias, nerval and vascular anatomy to/from and around the rectum and position adjacent to the male/female ventrally located sexual organs and pelvic vessels and – nerve structures [3–6]. The venous blood from the lower two rectal thirds is flowing via the internal iliac veins and the inferior caval vein into the lungs, from the upper third via the inferior mesenteric vein into the liver. The venous outflow of the colon is directed into the liver via the inferior (colon sigmoideum and colon descendens) and superior (transverse colon and colon ascendens) mesenteric veins into the liver. The arterial blood supply of the colon descendens, sigmoid colon and the upper rectal third comes from the inferior mesenteric artery, while the rest of the colon is supplied by the superior mesenteric artery. The lower two rectal thirds receive their arterial blood supply via the internal iliac arteries [7–10]. The lymphatic drainages of the rectum are led in parallel to the inferior mesenteric vein (upper third) or along the pararectal/internal iliac lymph streets (middle third) or along the inferior rectal artery (lower third) [11, 12]. The innervation of the rectum is supplied by the superior and inferior hypogastric plexus (superior plexus = N.sympaticus; inferior plexus = N.sympaticus and N.parasympaticus). These plexus not only are responsible for the pelvic organ function, including the lower two thirds of the rectum [12–15]. The nerve supply of the colon runs along the arterial vascular supplies as described above. Regarding the surrounding structures, the topography of the rectum, especially of the lower two thirds, is much more hazardous to the surgeon (plexus, internal iliac vessels, ureters, sexual organs etc.) than that of the colon (ureters, portal- and splenic veins, lower pancreatic edge) – of course with consequences to the skills required for the surgical procedures and the curative limits in T4 stages. Surgery of rectal cancers with the aim of sphincter preservation is significantly more demanding than surgery of colon cancer and the difficulties, such as anastomotic insufficiencies and/or nerval injuries, increase the further down the tumor is located.

The topographic position of the rectum and its function for the patient imposes more perception than the colon and for surgical treatment imposes more challenges and risks for malfunction and irreversible damage concerning continence and lesions of surrounding structures resulting in major bleeding or malfunction pelvic organs.

Macroscopically there are four forms of colon cancers: Bowel shaped and ulcerating (55-60%), polyp-cauliflower form of growth (25%), flat forms (15-20%, and diffuse infiltrating (1%). Exophytic growth is predominant in the proximal colon, while growth is endophytic ring shaped in the distal colon [16, 17]. RC may be growing exophytically, endophytically with ulcerations and intramural expansion or diffuse infiltrating with linitis plastica [12].

Colon and rectal cancers may have different macroscopic appearances.

In formal carcinogenesis 85-90% of the cancers arise from low grade or high grade intraepithelial neoplasias (LGIN, HGIN [18]) mainly in form of adenomas. These are classified as tubular (75%), villous (10%) or mixed (15%) with a malignant transformation risk of 4.8% (tubular), 19% (mixed), and 38.4% (villous) [14, 19]. Most of the malignant tumors are mucinous or non-mucinous adenocarcinomas, others have signet ring, anaplastic or squamous cell differentiation with worse prognosis [20]. Low risk cancers (L0) have high or intermediate differentiation (G1, G2) high risk cancers (L1) have a bad or undefinable differentiation (G3, 4) [3, 17, 18, 21].

CC´s and RC´s epidemiologically usually are registered as CRC´s. The incidence of CRC in Europe is higher than in Africa or Asia, but lower than in the US [22, 23] and is associated to nutritional habits concerning fat- and meat consumption [24]. The sex distribution in CRC disease favours male (53%) vs. female (47%), but the risk to develop a RC in males is 1.5 the risk in females, while females are predominant in developing cancers in the proximal colon (46% females vs. 38% males (1.2:1)). In the last four decades there was a “shift to the right” with increasing incidences in the right hemicolon; currently 15-35% of the cancers are located in the rectum, 25% in the right hemicolon [25–30]. According to the statistics of the American Cancer Society in 2015 [31] out of 129 700 newly registered CRC´s 93.090 (72%) cancers were diagnosed in the colon, and 39.610 (28%) in the rectum, resulting in a proportion of 2.5:1 (CC:RC). This may suggest that the carcinogenic risk in the colon is higher than in the rectum.

There is a shift to the right meaning that the incidence of CC is increasing, that of RC decreasing.

To our analytic calculation, however, the carcinogenic risk in the rectal mucosa by far exceeds that in the colon mucosa due to the fact that the area at risk in the colon definitely is larger than that of the rectum. The area simply can be related to the length of the colon (150 cm) or rectum (16cm). Thus the incidence of CC in the US in 2015 per cm of the colon is 621cm-1 (93.090/150=620.6) vs. 2479cm rectum-1 (39.610/16=2478.6) resulting in a relation of at least 1:4. In other words, the rectal mucosa has at least 4x higher risk for malignant transformation than the colon mucosa, which either depends on various susceptibilities to carcinogens or to various carcinogenic processes in the colon and in the rectum.

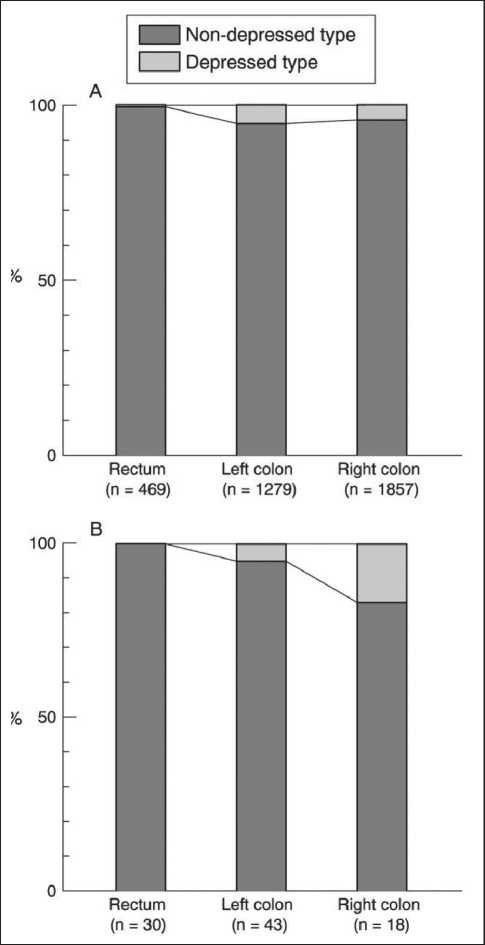

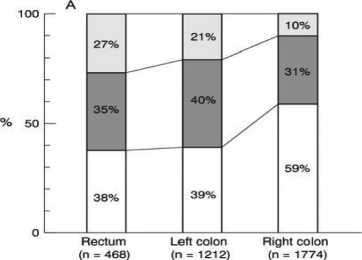

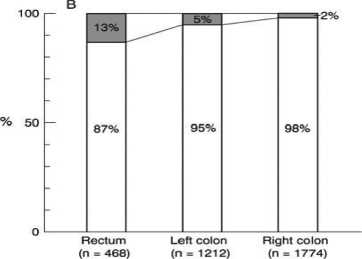

Histopathologically in early CC´s and RC´s mucosal lesions (polypoid, nondepressed type) are more frequently located in the colon than in the rectum (right hemicolon 51%, left hemicolon 35%, rectum 14%), while submucosal lesions more frequently occur in the rectum (Figure 1a); mucosal lesions with villous components were found more frequently in the rectum

(right hemicolon 2%, left hemicolon 5%, rectum 13% [32]. The absolute values for frequency of mucosal/ submucosal lesions of the depressed type are higher in the rectum than in the right colon. (Figure 1b) [32]. The Japanese authors describing this phenomenon suggest that different carcinogenic mechanisms are the reason for this differing histopathologic appearance of colon vs. rectal cancers [32].

In CC mucosal lesions are more frequent than inRC, in RC submucosal lesions are more frequent.

The difference in the incidences of hereditary syndromes involved in the development of CC vs. RC implicates that the molecular carcinogenesis in CC seems to be different from that in RC. HNPCC manifests predominantly in the colon/proximal colon, while FAP predominantly is causing the cancer in the distal colon or rectum, but also occurs in the rest of the colon [33, 34]. Various characteristic differences between HNPCC and FAP are summarized in Table 1.

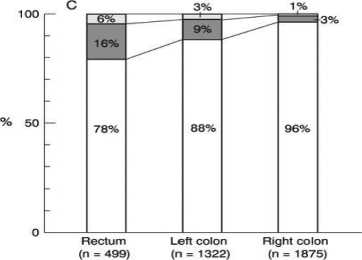

Macroscopically the APC type shows polypoid growth, while the growth pattern of the MSI type is flat. MSI types more frequently occur in the right colon (44% in the right colon vs. 25% in the left colon; p<0.01), while polypoid cancers are more frequent in the left (59%) vs. right (40%) colon (p<0.01) [35]. The flat growing early precursors of early cancers are significantly more difficult to detect than the polypoid growing early cancers [35–37].

HNPCC predominantly occurs in the right colon, for APC there is no predominance. CC and RC from a molecular biological point of view may be regarded as MSI- or APC types. MSI types are more frequent in the proximal colon and flat, APC types are polypoid. CC and RC differ in their chromosomal and molecular profiles as well as in enzyme expressions. There is no clear cut boundary between rectum and descending colon [38].

When regarding all CC´s vs. RC´s in their molecular carcinogenic alterations, differences in molecular profiles and enzyme expressions between CC and RC become evident (Table 2). For example, MSI more frequently is detected in proximal CC´s than in RC´s [39–43] which is also the case in HNPCC patients [34, 44–46]. When compared to RC, proximal CC´s more frequently show mutations in BRAF (Serin/Threoinin-Kinase- V600E [41, 47, 48], the expression of the CPG-Island Methylator-Phänotype (CIMP) [49–51], high gene expression of HOX [50] and CDX2 [52], increased mutation of KRAS [53] and higher levels ofactivated MAPK-signal transduction pathways [54]. In distal CC and in RC the following changes/molecular characteristics are more frequent when compared to proximal CC: Positivity of chromosome instability / CIN) [49], stability of microsatellites (MSS) [33, 34, 55], which is also the case in FAP [56]. The genes for EGFR or HER2 are amplified [57], p53 is mutated [58, 59], Wnt-signal-pathways in carcinogenesis activated [44, 60–62] in favour of distal CC´s and RC´s. The importance of p53 in carcinogenesis of colon and rectal cancer has been extensively described by Harris [63]. CC´s and RC´s also differ in protein expressions significantly, which are higher for Cyclin D3 and cMyc in CC (p<0.001) and for Cyclin D1, Cyclin E and Nuclear beta-Catenin in RC (p<0.001) [59]. High TS expression in CC correlates to better survival in the spontaneous course [58, 64, 65] or after adjuvant chemotherapy in CC [66–69]. Vice versa in RC, high TS either correlates to worse survival [70–72] or is meaningless [73]. The hereditary cancer syndromes HNPCC (2-7% of all “CRC”´s) and FAP (1% of all “CRC”´s) are differing in their molecular chromosomal changes [38]. FAP has an APC-Gene mutation (APC type; 60% of all “CRC”´s), while in HNPCC the germ chromosomes are mutated in their DNA information for MMR-genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS1, and PMS2) leading to MSI (MSI type) [44, 45, 74]. CC´s and RC´s may be categorized according to the features of the APC type (about 2/3 of CC+RC) and the MSI type [21, 75, 76].

Innovative for the classification of “Colorectal Cancer” were the findings of an international consortium analyzing molecular, enzymatic and immunogenic features and microscopic growth patterns including angiogenesis. With their data collection, the CRC Subtyping Consortium (CRCSC) defined four

Figure 1a: Comparison of the incidences of depressed and non-depressed types of neoplastic lesions in the rectum, the left colon, and the right colon. (A) Mucosal lesions, (B) submucosal cancers. A significant difference in the macroscopic type was noted between the rectum and the colon (p < 0.001). The incidence of depressed submucosal cancers in the right colon was significantly higher than that in the rectum (p = 0.0472). [32]

I I s5 mm I I >5, si О mm I I >10 mm

I | Absent I I Present

EH Adenoma EH Intramucosal EZl Submucosal cancer cancer

Figure 1b: (A) Relationship between the location and the size of non-depressed mucosal lesions. (B) Relationship between the location and the incidence of villous components in nondepressed mucosal lesions. (C) Locations of mucosal lesions and submucosal cancers. [32]

Table 1

Differences between FAP (familial adenomatous polyposis coli) and HNPCC (hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer)

Table 2

Differences in carcinogenesis, molecular genetic profile, histopathology, and biology of sporadic colorectal cancer compared with rectal cancer

|

Mutation/Expression |

Proximal colon cancer |

Distal colon and rectum cancer |

Author(s) |

|

Chromosome instability (CIN) |

NO |

YES |

[49, 56] |

|

Microsatellite instability (MSI) |

YES |

NO |

[39] |

|

EGFR and HER2 amplification |

NO |

YES |

[57] |

|

CpG hypermethylation(CIMP) |

YES |

NO |

[49] |

|

BRAF mutation (BRAF-like) |

YES |

NO |

[48] |

|

KRAS |

YES |

NO |

[59] |

|

p53 |

NO |

YES |

[58] |

|

HOX gene |

YES |

NO |

[50] |

|

CDX2 gene |

YES |

NO |

[52] |

|

Thymidylate synthase |

YES |

NO |

[70, 71] |

|

Cyclin D3 and c-Myc |

YES |

NO |

[59] |

|

Cyclin D1, cyclin E and nuclear β -catenin |

NO |

YES |

[59] |

|

Activation of MAPK-pathways |

YES |

NO |

[54] |

|

Activation of Wnt-pathways |

NO |

YES |

[44] |

|

Mucosal lesions (non-depressed type) |

YES |

NO |

[32] |

|

Submucosal lesions (non-depressed type) |

NO |

YES |

[32] |

|

Mucosal and submucosal lesions (depressed type) |

YES |

NO |

[32] |

|

YES –Often positive or frequent incidence, NO – often negative or rare incidence |

|||

Table 3

Effects of different prevention measures on the two cancer entities

|

Prevention measure |

Decreased incidence |

|

|

Colon cancer |

Rectum cancer |

|

|

YES |

NO |

|

|

Physical activity |

[53, 80, 81, 84–86] |

[81, 84–86] |

|

Low BMI |

YES |

NO |

|

[53, 86, 87] |

[86, 87] |

|

|

YES |

NO |

|

|

Reduced energy uptake |

[53] |

[87] |

|

NO |

YES |

|

|

COX-2 inhibitors |

in case of HNPCC |

in case of FAP |

|

(there are no sufficient data) |

[88–90] |

|

|

Aspirin |

YES |

NO |

|

[91] |

[91] |

|

HNPCC – Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer; FAP – familial adenomatous polyposis coli.

robust consensus molecular subtypes CMS1-4 [77]. Most interestingly, CMS1 tumors were frequently diagnosed in females with right sided lesions and presented with higher histopathological grade. CMS2 tumors were mainly left sided. CMS4 tumors tended to be diagnosed at more advanced stages (UICC III and IV) and displayed worse overall and relapse free survival (in the multimodal PETACCC-3 trial involving adjuvant CT in CC UICC III). After relapse (and treatment of relapse), survival was superior in CMS2 patients and very poor in the CMS1 population [77]. In our literature analysis looking at various factors relevant for CC and RC on the molecular and protein level, many of them included in the CRCSC-analysis, we found out, that the proximal colon and the distal colon+rectum show evident differences in expression (Table 2). The multi-omic analysis of CC´s confirmed the substantial differences between right- and left sided CC on the molecular genetic level [78].

A difference in carcinogenic principles might also be the reason for the different effectivity of primary preventive measures by physical activity, as pointed out in a review in 2000 on the impact of nutrition and physical activity on the development of CC/RC [79]. It now has been reported by various groups that physical activity at higher levels might reduce the incidence/risk for CC [80–83] by up to 40%, but has no influence on the incidence/risk for RC [81, 84–86]. In the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort involving 70.403 men and 80.771 women, the risk for CC was significantly reduced by 16% (RR 0.84, 95% KI 0.59-1.20) in participants practicing actively sports (79% of all study participants), while this was not observed in RC [85]. The results of various preventive trials involving sports activities, BMI, reduced energy intake or medical intervention with COX-2-inhibitors or aspirin are summarized in Table 3.

In summary, CC differs from RC in terms of molecular biological parameters. CC may be prevented by physical activity, while this cannot be achieved to prevent RC.

Discussion

In terms of epidemiology “CRC” has varying incidences, when continents/civilizations are compared. The male: female ratio in US statistics for incidences 2006-2010 was 1.3:1 in all CRC, but 1.6:1 in RC [29]. The location during the decades shifted from the left/rectum to the right [26, 92], and meanwhile patients with cancer in the right colon are older and more frequently females than males [28]. The most frequent locations are the right hemicolon (48%) and the rectum (28%) [29]. Up to now there are no exact data to show, whether the proportion CC:RC shows a difference in the various continents analyzed. In the Western countries, two thirds of “CRC” is located in the colon, one third in the rectum [3, 23, 29, 92]. This implicates, that the colon is more susceptible to develop cancer than the rectum, which is not the case. We set the 2015 US-incidence in proportion to the length of the organ at risk (colon 150 cm, rectum 16 cm) and came to the conclusion, that the rectum mucosa is four times more prone to malignant transformation than the colon mucosa!.

In the Western countries from a macroscopic/ histological point of view colon cancers may have different growth patterns than rectal cancers [22, 23, 92]. The appearance of flat lesions (depressed type) is more frequent in the colon than in the rectum [32], thus more difficult to detect as early cancers, while the polypoid nondepressed types with villous components (easier to detect) were more frequent in the rectum [32]. The authors contributed their observation to possible differences in carcinogenesis colon vs. rectum [32]. When looking at the formal carcinogenesis, one first has to begin with analyzing differences in the most frequent autosomal dominant inheritable “CRC” cancers, HNPCC and FAP. HNPCC preferably is located in the right hemicolon, with FAP cancers there is not such a clear preference, but there is a tendency to left hemicolon- or towards the rectum cancers. Both entities differ substantially in their abnormalities on the chromosomal/DNA-mutational and enzymatic levels. FAP is an obligate precancerous disease; HNPCC may still be regarded as facultative, but has an expression rate of 50-70% [21]. The basis for FAP is an inherited mutation in the APC Gene (initiation) with the consequence of several carcinogenic steps (promotion). About 60-70% of sporadic CC and RC´s have the same “APC-type” formal carcinogenic pathway [21, 93–96]. In HNPCC, a mutation in the mismatch repair gene family (MMR) is the germ defect responsible for a sequence of molecular changes which eventually lead to CC or, rarely, to RC and, in addition to cancers of extracolic adenocarcinomas (CC only: Lynch-Syndrome I, CC and extracolonic cancers: Lynch-Syndrome II) [44, 45, 74, 95, 97, 98]. The gene-defect, responsible for the HNPCC type of cancer is detected pathologically (PCR or Immunohistology) in the tumor tissue as “Microsatellite“in the inheritable syndromes, but also in sporadic cancers which are classified as MSI-type CC or RC.The in male to female proportions in tumor locations ( e.g. males get more RC than females, and females more proximal CC´s than males and the shift of “CRC” incidences to the right, and the preferred locations either in the (proximal) colon (HNPCC´s or MSI-type noninheritable “CRC”) or in the distal colon/ rectum (APC type of “CRC”) and our hypothesis to carcinogenic susceptibility (see above) all support our hypothesis, that CC and RC are different tumor entities in terms of carcinogenic processes. When various alterations on the chromosomal- , gene- or protein levels were analyzed in the tumor tissue, marked differences between the “proximal colon” and the “distal colon and rectum” appeared (see Table 2). The possibility to prevent CC by (high) physical activity, but not RC indirectly supports our conclusion, that major carcinogenetic processes in CC are dissimilar from RC.

Very interesting and new findings concerning the classification of CRC´s were generated by the CRCSC Subtyping Consortium in 2015: The group subclassified “CRC´s” from 4151 samples/patients (according to various features from the molecular up to the histopathologic and immunogenic levels (27 unique subtype labels)) into the four distinct subtypes CMS1-4. (and an additional “mixed group”) using a very heterogenous tumor population from CC and RC patients with/without surgery, with/without multimodal therapy, with a variety of multimodal treatments, and applied various analytical methods and very sophisticated biometrics. The groups CMS1-4 had various distinct biological properties. Most interestingly, two of the CMS-groups were associated to embryologically different parts of the colon: CMS to right sided lesions, and CMS2 mainly to the left sided lesions [77]. The tumor tissues/data were supplied by 6 different working groups who either had their data from “CRC”- or CC- samples/patients. There was no distinct differentiation between CC and RC [77]. In spite the facts that no separate views seem to have been shed on CC primary tumors as a whole vs. RC primary tumors, and that 858 patients/samples from primary tumors were excluded from the primary analysis, the new system implies, that the large bowel cancers seem to have significantly different characteristics, which eventually may become relevant for treatment individualization accordingto these groups. CRCSC proposes a new taxonomy of colorectal cancer reflecting significant biological differences in the gene expression-based molecular subtypes, which is supported by others [78, 99, 100]. We are thinking that this demand for a change in looking at “CRC” with a very complicated classification system is generalizing too early and mainly based on a molecular primed classification view. More facts need to be respected for dividing the term “CRC” in organ related taxonomic entities.

Various prognostic molecular or enzymatic factors have been tested in CC, RC, and “CRC” in the spontaneous courses or in multimodal therapy with the aim to have a better individualized treatment- and/ or patient selection to avoid unnecessary potentially toxic CT´s or RCT´s. We and a few other groups[101, 102] were the first to study the potential role of TS and DPD to individualize patient selection for adjuvant/ neoadjuvant and for palliative treatment in “CRC” [67, 79, 103] and conducted the first prospective randomized trial for treatment of metastases [104], always in translational projects with the USC Cancer Center in Los Angeles and the laboratory of P.V. and K.Danenberg, coworkers of the late Charles Heidelberger (teacher and inspirator of one of the authors (K.H.L.) to introduce individualization to surgical oncology). Up to now, there is a tendency in results from multimodal trials, that these molecular prognostic factors, e.g. TS and DPD, may be used for treatment individualization – with different results in CC- vs. RC-multimodal treatment. E.g. low TS might be associated with a benefit from RCT+CT in RC, and high TS in adjuvant CT of CC. Reimers et al. have suggested a cocktail of modern prognostic factors for patient selection in neoadjuvant treatment of RC [43], however, this approach due to the lack of unanimous convincing data obtained by best methods determined in translational research consensus is far from routine yet.

Regarding our findings, we strongly suggest to accept CC and RC as different tumor entities in all aspects of experimental and clinical research. The term “CRC” should be historical.

Summary and conclusion

We collected data on various relevant levels to question the term “colorectal cancer” and, if indicated, suggest to replace it by “colon cancer” (CC) and by “rectal cancer” (RC) separately, if the tumor is located/has been the origin of the primary tumor in the corresponding location. Basic and clinical research groups should respect this change of nomenclature. With our ample experience in carcinogenesis, prevention, surgery and multimodal therapy of primary CC and RC primary tumors and their metastases and in treatment individualization by molecular/cell culture methods and on the basis of the following collected data/experiences we think, that this recommendation is justified. The CMS system suggested by the CRCSC group also suggests taking a distinct look at the broad nondifferentiating term “CRC”. Our opinion, that CC and RC are distinct tumor entities is supported by the facts that CC and RC seem to be submit two different pathways in initiation and promotion (carcinogenesis: HNPPC and MSI type of CC mainly located in the proximal colon, FAP and APC type without clear preference, but a tendency to the left colon and to the rectum), have a different susceptibility to/way of carcinogenesis (rectal mucosa is four times more susceptible to malignant transformation than colon mucosa) and to preventive principles in carcinogenesis (active sports may prevent CC (up to 40%), but not RC), that tumors shift to the right and female sex is dominating in proximal (right) CC´s (due to a change of carcinogenic principles). The clinical parameters of differences between CC and RC, such as in surgical techniques with morbidity/mortality and long term results, the responses and toxicities (= the benefit) of multimodal therapy (MMT) and molecular/clinical prognostic factors in the spontaneous course and after MMT, are analyzed and reported in a separate paper [105]. CC and RC have different profiles from the view of many preclinical (and clinical) parameters.In basic and translational research concerning “CRC”, Colon Cancer (CC) and Rectal Cancer (CC) should be regarded as different tumor entities. CC may even be subdivided in right sided CC and left sided CC (and male vs. female).

Список литературы Colon and rectal cancer are different tumor entities according to epidemiology, carcinogenesis, molecularand tumor biology, primary and secondary prevention: preclinical evidence

- Link K.H., Kornmann M., Staib L., Redenbacher M., Kron M., Beger H.G.; Study Group Oncology of Gastrointestinal Tumors. Increase of survival benefit in advanced resectable colon cancer by extent of adjuvant treatment. Ann Surg. 2005 Aug; 242(2): 178-87.

- Kornmann M., Staib L., Wiegel T., Kreuser E.D., Kron M., Baumann W., Henne-Bruns D., Link K.H. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy of advanced resectable rectal cancer: results of a randomised trial comparing modulation of 5-fluoruracil with acid or with interferon-alpha. Br J Cancer. 2010 Oct 12; 103(8): 1163-72. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605871

- Pox C., Aretz S., Bischoff S., Graeven U., Hass M., Heußner P., Hohenberger W., Holstege A., Hübner J., Kolligs F., Kreis M., Lux P., Ockenga J., Porschen R., Post S., Rahner N., Reinacher-Schick A., Riemann J., Sauer R., Sieg A., Scheppach W., Schmitt W., Schmoll H.J., Schulmann K., Tannapfel A., Schmiegel W. S3-Leitlinie „Kolorektales Karzinom". Z Gastroenterol. 2013; 51: 753-854.

- Heald R.J., Moran B.J. Embryology and anatomy oft the rectum. Semin Surg Oncol. 1998; 15: 66-71.

- Köckerling F., Lippert H., Gastinger I. Fortschritte in der kolorektalen Chirurgie. Hannover, Science Med, 2002. 204.