Creative Tourism Through Cooperation Networks: Balancing Uniqueness and Commonality. Insights From Institutional Theory

Автор: Pimentel T. D., Hernandez Matorel M., Lopez Meza M.

Журнал: Креативные индустрии | Creative Industries R&D @creativejour

Рубрика: ТЕОРИЯ И МЕТОДОЛОГИЯ КРЕАТИВНЫХ ИНДУСТРИЙ | THEORY AND METHODOLOGY OF CREATIVE INDUSTRIES

Статья в выпуске: 1 (2), 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Creative tourism posits the generation of differentiated experiences, wherein tourist destinations would provide the foundation for such experiences. Paradoxically, the very expansion and popularization of creative tourism destinations, which specialize in crafting “personalized tourist experiences,” tends to lead to their saturation, and their product become homogeneous. This raises the question: to what extent is there a differentiation or a standardization of management practices in the pursuit of distinctiveness? This conceptual article analyzes the network of creative tourism cities, employing institutional theory as a theoretical lens, focusing on its isomorphic process of creativity and the pasteurization of “unique experiences”. It is argued that the consolidation of this phenomenon stems, in part, from the integration into these networks. This dynamic relates to the inclusion of other actors as part of the destinations’ external environment and to the isomorphism in both the activities offered and the marketing practices, which positions them as belonging to these networks. However, while this facilitates the network’s organizational and promotional processes, it incurs an internal contradiction, as it homogenizes that which is purported to be unique, because more and more the cities and experience that they offer become similar.

Creative Tourism, Cooperation Networks, Institutional Theory

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/14134261

IDR: 14134261 | УДК: 338.48-44(1-21) | DOI: 10.7868/S3033671625020011

Текст научной статьи Creative Tourism Through Cooperation Networks: Balancing Uniqueness and Commonality. Insights From Institutional Theory

Tourism as an economic activity is recognized as being in a general state of growth. The World Tourism Organization’s (UNWTO) Tourism Barometer affirms that in 2019, the number of international tourist arrivals reached 1.458 million, representing an approximate growth of 3.5% and 9% relative to the arrival numbers of 2018 and 2017, respectively. Furthermore, it highlights that tourism revenues in 2019 totalled 1.478 billion dollars, compared to the 1.457 billion dollars contributed by the sector in 2018.

This scenario makes tourism a significant matter for all types of institutions, both public and private, for public institutions, due to their role as part of the tourism superstructure, and for private ones, due to the recognition of emerging demand in the niche and the profitability this can generate for their businesses. However, beyond adhering to the mandates of various organizations, tourism is recognized as an economic activity constituting its own field, with distinct practices, actors, effects, and structures.

For example, Picornell (1993) highlights negative impacts of tourism, such as investment flight, inter-sectoral competition, over-reliance on tourism, inflation, the demonstration effect, and seasonal fluctuations. Similarly, Rubí-González and Palafox-Muñoz (2017) identify effects like inequality, labor flexibilization, job insecurity, and tourism’s role in fostering poverty. At the end of the 20th century, Nash (1989) noted acculturation as an adverse consequence of the influx of different cultures in tourist areas. In this context, creative tourism offers a way to experience local realities more closely and engage with culture authentically, allowing for a new perspective on tourism services.

In the shift from cultural to creative tourism, many visitors have moved from exploring heritage sites, monuments, museums, or cultural products to participating in fashion, design, media, entertainment, lifestyles, cuisine, traditions, atmospheres, intangible heritage, architecture, nightlife, beliefs, cultural diversity, events, and place-based experiences (Barrera Fernandez & Hernandez Escampa, 2017; Rivera Mateos, 2013).

Creative Tourism

1.0

It is characterized by Richards' first conceptualization and Raymon (2000) alluded to a tourism that was growing based on learning workshop practices in supply-driven tourist destinations.

Creative Tourism

2.0

Creative tourism is already recognized as a means of local development, innovation and territorial planning for tourist destinations by organizations such as UNESCO.

Creative Tourism

3.0

This phase of creative tourism brings with it more strengthened tourism networks through creativity, the inclusion of cultural and creative industries in the tourism offer.

----------------1

Creative Tourism 4.0

From this phase onwards, the experiences of creative tourism begin to be addressed, due to their active participation, the relationship between production and consumption (cocreation) that occur in destinations from the development of this tourism.

Figure 1 – Conceptual evolution of creative tourism

This perspective also allows us to view creative tourism through Molina (2016), who states that creative tourism is no longer regarded as just a business but as a social necessity and a tool for genuine sustainable, economic, and social development, framing it as a developmentalist position. In this context, it is important to highlight that creative tourism is approached from the experience economy as a theoretical paradigm, which mainly relies on the idea that goods and services are offered as experiences.

Within this paradigm, places and environments play a crucial role in staging these experiences. Additionally, various authors acknowledge the significance of tourist destinations in creating spaces for creative experiences for visitors through public spaces (Maitland, 2010), as well as the management of creative events, spaces, and shows as settings for generating creative experiences (De Bruin & Jelinčić, 2016;

As this emerging form of tourism gains recognition and destinations start adopting these practices via global cooperation networks, there is a potential risk of commodifying tourist experiences. This results in a situation where existing cooperation frameworks show that practices are increasingly similar, especially regarding creative tourism, its unique aspects, and how it creates value.

Considering the above-mentioned context, this paper examines creative tourism from the viewpoint of destinations as creators of spaces that promote the consumption of creative experiences, grounded in institutional theory. This approach helps track the development of this emerging tourism niche as a phenomenon and its strengthening within tourist destinations, influenced by the practices of the Creative Tourism Network and UNESCO Creative Cities Network. The main goal of this study is to analyze how these networks’ practices contribute to establishing creative tourism organizationally in destinations. It aims to answer: To what extent are creative tourism practices distinct in destinations due to the collaborative experiences within these networks?

-

2. Institutionalism as an Approach to Creative Tourism: Consolidation or Contradiction?

Institutionalism is a 20th-century theoretical perspective highlighting the significance of institutions as key societal actors and important resources for social action. Although mainly examined through political institutions, it has influenced diverse social sciences and continues to illuminate the role of organizations in post-industrial societies. This approach advocates for a regulatory and normative framework rooted in the State’s authority over institutions, facilitating effective organization. It also stresses organizational conformity driven by social rules.

Hall and Taylor (1996) outline three key approaches to the new institutionalism that developed during the 1980s and 1990s: historical institutionalism, rational choice institutionalism, and sociological institutionalism. Historical institutionalism emphasizes how institutions are embedded within their procedures, norms, and practices, highlighting the connection between individual behavior and institutional structures. Rational choice institutionalism integrates rationality as a central factor for understanding human behavior and its effects on organizations. Conversely, sociological institutionalism focuses on organizational culture and individual actions, suggesting that institutions originate from the accumulated social actions of individuals over time.

Alternatively, Peters (1999) identified seven approaches within neo-institutional theory: 1) normative institutionalism, 2) rational choice institutionalism, 3) historical institutionalism, 4) empirical institutionalism, 5) sociological institutionalism, 6) interest representation institutionalism, and 7) international institutionalism. This diversity of approaches enables the theory to adapt across multiple disciplines, extending beyond public administration and political science, and facilitating the study of institutions themselves.

Considering the embeddedness of social action within the productive process of tourism, which refers to how networks influence tourist destinations through the collective efforts of various actors, and in light of tourists’ increasing interest in consuming creative experiences during their visits to destinations, four key theoretical postulates are used in the study of creative tourism to understand how this phenomenon becomes established.

The initial key aspect is the external environment’s relevance, a central concept in institutionalization theory. It applies pressure to organizations, often represented by other institutions. DiMaggio and Powell (1991) categorized three types of environmental pressures: coercive pressure from formal and informal influences; mimetic pressure, where organizations emulate others; and normative pressure, which involves upholding core and competitive standards.

Another key tenet of institutionalism is the significance of strategic interaction among actors within networks, a concept that becomes even more prominent with rational choice institutionalism. This approach generally sees political institutions as frameworks of voluntary cooperation designed to address collective action problems and benefit all involved parties. Consequently, the connection between institutions and other actors becomes more meaningful, as it facilitates understanding peers and promotes teamwork toward shared goals (Caballero Míguez, 2007).

Pérez-Ramirez (2019) advocates for cooperation within networks for institutions, noting that networks are extensively employed to better understand complex issues because they facilitate sharing information, resources, and skills to address challenges more efficiently (p. 33). Therefore, cooperation is seen as a network of actors working together not only to solve problems but also to pool resources for shared objectives.

This expands the theoretical discussion of institutionalism by focusing on the regulatory and normative frameworks that serve as public mechanisms of organization and political action within this theory. Vargas (2008) emphasizes the regulatory, normative, and cognitive pillars necessary to understand large-scale transformations in national systems. These pillars involve institutional transition, upheaval, and imperfection, offering insights into the comparison of national business systems based on institutional embeddedness. They also help explain why organizations tend to adopt similar practices under isomorphic pressures and highlight the constraints on spreading and embedding these practices across different countries and multinational entities. Moreover, these concepts clarify the interactions between multinationals and their host environments, particularly through legitimacy and the liability of foreignness.

While it offers a highly institutionalized view from a public perspective, it does not lessen the importance of these regulatory and normative frameworks in the practical application at smaller scales. These frameworks help maintain some control over inter-institutional relationships, leading to the idea of organizational practice similarity, or isomorphism in this context. Scott W. (1995)

defines isomorphism as the extent to which organizations or individuals share the same practices. DiMaggio and Powell (1991) also note that once organizations establish connections with others, they tend to become more alike. Therefore, isomorphism demonstrates how environmental pressures, such as similar actors and shared norms, can drive institutions to adopt similar practices.

This review suggests that creative tourism allows tourist destinations to participate in cooperation networks. These networks enable destinations to be recognized as organizational actors and influence their practices as tourist centers. By linking institutional theory to the organizational level of actors within specialized cooperation networks, it becomes possible to identify key characteristics that are crucial for understanding the dynamics of tourist centers.

In this context, the external environment, interactions with other organizations, normative and regulatory frameworks, and isomorphism were identified as key categories for analysis in the research development (see Table 1). This highlights the similarities and differences in their practices as actors within networks that concentrate on this emerging tourism niche.

Table 1 – Analytical categories and their operational definition

|

Analytical Categories |

Definition |

|

External environment |

Recognized as all external pressures exerted on an institution and that have a direct and indirect influence on organizational development |

|

Relationship with other organizations |

Relationships maintained by an organization based on an end and which allow it to cooperate based on a common objective |

|

Regulatory and normative frameworks |

All mechanisms recognized as norms or regulations that enable organizations to control their inter-institutional relations |

|

Isomorphism |

A trait that indicates a shared feature in an institution’s organisational practices, observable through its interactions with other institutions |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

-

3. Research Method

-

4. The practices of the Creative Tourism Network and the UNESCO Creative Cities Network

-

4.1 Object of research, its characteristics and contextualization

The UNESCO Creative Cities Network, established in 2004, is an international organization aimed at fostering collaboration among cities that view creativity as essential for sustainable urban growth. It now includes 246 cities committed to placing creativity and cultural industries at the core of their local development strategies, while also partnering with other stakeholders in the sector.

-

-

4.2 Characteristics and contextualization

The external environment is very important for institutionalism. Tourists, the local population, and local tourism organizations in a destination become sources of information for the development of creative tourism in a region. Although Molina (2016) relates that creative tourism is not an adaptable model in every destination, as the reality of each place is different, destinations are striving to work together as a way to seek information that allows them to meet the needs of tourists, adopt creative tourism as a means of local development for receiving communities, and create a structure that allows for the accentuation of a tourism offer friendly to this contemporary tourism.

The current study examines creative tourism networks to understand how creative tourism establishes itself in tourist destinations from an institutional perspective. It employs a qualitative, exploratory-descriptive approach. The study focuses on the Creative Tourism Network and the UNESCO Creative Cities Network, which together encompass approximately 260 localities that utilize creativity as a driver of development. These networks also integrate cultural and creative industries into tourism to create innovative travel experiences.

These networks were examined through a content analysis of their reports and documents accessible on their websites. The goal is to understand how these networks relate to each other by identifying their practices, using analytical categories such as review of the external environment, interactions with other actors, regulatory frameworks that oversee participation, and ultimately, the isomorphism in their creative tourism practices.

Founded in 2010, the Creative Tourism Network promotes destinations that harness creative tourism to meet travelers’ demand for unique experiences and to foster a value chain within their region. Destinations within this organization are designated as “Creative Friendly Destinations”, officially accrediting their membership in the network. Additionally, the organization engages in research led by renowned academics, such as Greg Richards, along with offering consulting services, as well as academic and professional training.

The entity recognizes various services, including consulting and project monitoring; training for universities, business schools, DMOs, private companies, and public organizations through courses, conferences, seminars, workshops, training programs, or support for specific projects; and the planning and organization of events related to creative tourism (Creative Tourism Network, 2014).

Although it is not recognized as a network whose objective is adapted to creative tourism, there are authors such as Herrera-Medina, Bonilla-Estévez and Molina-Prieto (2013), who point to creative cities as scenarios that start from the premises of the knowledge economy and the economy of creativity, which rethink economic development through creativity, knowledge and its management. In this way, creative cities can be recognized by elements of the creative economy, such as the importance of heritage architecture and urban events (festivals and carnivals, etc.), as drivers of tourism, and also as a source of work, roots and identity for citizens; or the strengthening of creative and cultural industries as generators of economic and social well-being.

In general, the concept of creative cities has a longer trajectory than creative tourism, as it is a concept that is taken up from the economy of creativity and not from the economy of experience, however, there are authors who attribute this UNESCO program to the phenomenon of creative tourism (Ovalles, 2017; Paretl & Garcia, 2020; Picco, 2019). In turn, the Creative Cities Network (cited in Solórzano, 2015) reports that cities applying to join the network aim to become centers of creative excellence, helping other cities cultivate their own creative economies through creative tourism.

Therefore, on the page of the Creative Tourism Network and the Creative Cities Network, they agree that the groups interested in these topics go beyond locals, tourists, and the tourism offer, by mentioning other destinations, consultants, public institutions, academic researchers, project managers, media, fairs, and exhibitions, as these are recognized for having a direct and indirect impact on the region’s tourism and become sources of information and visibility. Furthermore, in the case of the Creative Cities Network, the existence of academic groups, research and extension groups, and inclusion projects are much more valued, as they recognize that by focusing on creativity as the central axis of a region’s economic activities, different themes are included in the destinations’ development agenda. It also focuses on public institutions for the role they play in local governance.

For this reason, on the page of the creative tourism network and the creative cities network they agree that the groups interested in these topics go beyond locals, tourists and the tourist offer, these mention other destinations, consultants, public institutions, academic researchers, project managers, media, fairs and exhibitions, as these mentioned are recognized for having a direct and indirect impact on tourism in the region, they become sources of information and visibility. In addition, in the case of the Creative Cities Network, the existence of academic groups, research and extension groups, inclusion projects are much more valued, as they recognize that betting on creativity as the central axis of economic activities in a region, different themes are included in the development agenda of destinations, it also bets on public institutions for the role they play in local governance.

Conversely, collaborating with different organizations is a significant topic within the analyzed information since networking fundamentally involves working together with other actors on shared themes. In the case of the Creative Cities Network, the benefit of network cooperation is acknowledged as a way to share experiences and practices, foster greater collaboration, and inspire other members to develop local policies that emphasize the value of creativity and sustainable development. Its network is organized with a secretary overseeing the network, seven sub-networks focused on various approaches to creative cities, and a coordinating committee. Meanwhile, the Creative Tourism Network also highlights its visibility as a network (B2B and B2C), although no detailed structure is publicly available, aside from the existence of Creative Friendly destinations and creative platforms.

In this sense, tourist destinations as actors in the network are obliged to cooperate with others, share their practices, engage in continuous improvement, and abide by codes of ethics and practices. This is exemplified by the Creative Tourism Network, which includes themes such as respect for local traditions, the need for learning activities and workshops, promoting ecotourism, benefiting involved actors, providing training on related issues, involving economic sectors and local institutions, actively participating in experiences, creating diverse and inclusive activities, and encouraging value chains that include local residents. Additionally, they study the effects on this population, make use of social networks, and involve artists and artisans in tourism decision-making.

The Creative Cities Network comprises 246 cities across various categories as listed by the agency (Fig. 2), while the Creative Tourism Network includes only 26 destinations within its network (Fig. 3). Both networks have a presence on five continents; however, the Creative Tourism Network is more concentrated in European destinations. In contrast, the Creative Cities Network is more widely spread across various regions globally, probably due to its connection with an international organization such as UNESCO, which offers it enhanced governance and recognition in cultural heritage issues.

Figure 2 – Map of UNESCO Creative Cities

Source: Retrieved from UNESCO (2021)

Figure 3 – Map of the Creative Tourism Friendly Destinations

Source: Retrieved from the Creative Tourism Network (2014)

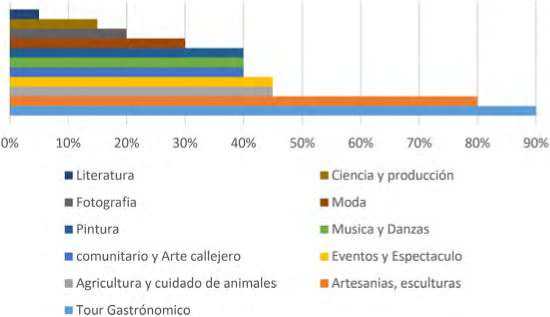

Regarding the practices of this group of creative tourist destinations, it can be mentioned that the Creative Tourism Network relates information from 20 tourist destinations in which 90% of them offer creative experiences related to gastronomy and culinary arts, 80% have an offer related to crafts, sculpture, ceramics, and pottery, another 45% also point to experiences of events and shows, 40% with community tourism and arts in the streets of the destination, 40% also relate to music and dance workshops, 40% with painting experiences, 30% with fashion workshops, 20% with photography, 15% with production stages of some local good, and 5% with literature experiences (Fig. 4).

Figure 4 – Type of creative experiences in the Creative Tourism Network (CTN) Source: Own elaboration based on creative experiences published on the Creative Tourism Network page

Additionally, 70% of the creative experiences recorded in the 20 tourist destinations are learning workshops typical of creative tourism. Moreover, 85% of these destinations are recognized as being friendly to creative tourism and have a presence on social networks such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, enhancing their visibility in this area.

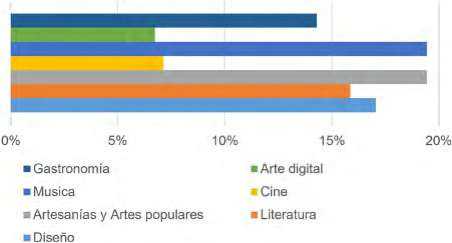

As for the Creative Cities Network, it has its own categorization where cities, when applying to this network, must choose one of the approaches based on the cultural elements that most coincide with the network. In this way, 19% of the cities are related to the category of crafts and folk arts, 19% of the creative cities are in the musical field, another 17% in terms of design, 16% of these cities in literature, 14% of the creative cities in gastronomy, 7% in cinema, and another 7% in digital art (Fig. 5).

Figure 5 – Percentage of Creative Cities by category

Source: Prepared by the authors based on related information on the UNESCO Creative Cities Network website

This network’s main goal is not directly connected to creative tourism, so it does not specifically highlight the creative experiences offered in each member city. There is only superficial information about some interaction with tourism in certain cities, but nothing detailed. Additionally, some creative cities utilize a website and social media to promote their creative activities. In some cases, these efforts to enhance the destination’s visibility online are led by the city’s tourism department.

In this way, it is recognized that the tourist practices in the destinations belonging to these networks assume isomorphic characteristics, because when working together they begin to share information between the agents of the networks and, thus, work under the same vision and objectives; this isomorphic characteristic is also recognized in the marketing practices of the cities that are part of these networks, as is the case of most of the Unesco creative cities, which have a website, where they list the projects that are part of the creative city project locally, also mentioning the city’s agenda, photographic galleries, it also includes the local governance that is part of the creative city project (Fig. 6).

Figure 6 – UNESCO Creative Cities Sites

Moreover, the Creative Tourism Network specifically recognizes the use of web pages that promote this type of tourism. Most destinations within the network utilize the city’s brand, a marketing strategy that increases the visibility of tourist destinations both nationally and internationally. This approach leverages the existence of creative tourism as a key element to enhance the destination’s appeal (Fig. 7).

Figure 7 – City brand of the Creative Tourism Network destinations

Source: Creative Tourism Network, 2014. Retrieved from:

-

4.3 Discussion and interpretation of cooperation networks observation

Linking creative tourism with theories like institutionalism helps establish tourist destinations as key players in developing this market niche. This role is acknowledged across various theoretical approaches. Authors like De Bruin and Jelinčić (2016), Maitland (2010), and Richards and Wilson (2007) concur that tourism experiences can be created in locations that can be managed, planned, or developed for visitors. This highlights an opportunity for tourism stakeholders in various regions worldwide to develop these areas.

Networking and collaboration between creative cities offer numerous benefits for tourist destinations from an organizational perspective. It also enhances the destination‘s overall organization and global visibility, aiding in the consolidation of creative tourism activities that may have been impacted by earlier practices of other stakeholders. Therefore, it aligns these cities through many shared activities and projects that promote creative tourism.

This suggests that tourist destinations can strengthen their unique appeal through this form of collaboration. Regarding UNESCO’s Network actions, their efforts do not primarily focus on tourism but aim to foster economic and local development via creativity, showing how these cities generate many opportunities for activities within their areas. When tourists visit with these goals in mind, they will find these spaces enjoyable. However, with the Creative Tourism Network, it is a more specific issue. Its goals focus on growing this niche, which can be seen in tourist destinations’ interest in providing visitors with creative experiences.

Regarding the similarities identified in tourist destinations incorporated into these networks, considering the proposed analysis categories (see Table 2), the ability of these collaborations to include other actors in the tourism setting is highlighted. These actors typically include tourists, entrepreneurs, the host community, and institutions. However, in this kind of network, the academic community‘s involvement is realized through research, management projects, and local initiatives, among others. Vargas (2008) discusses the organizational perspective, emphasizing how adaptation processes reshape the structures of actors and institutions. This demonstrates how these cities, when integrated into cooperation networks, led to the inclusion of new actors in the tourism agenda.

Regarding isomorphism, it was observed that the actors within the cooperation networks share characteristics, as noted by DiMaggio and Powell (1991), linking this trait to other organizations. Consequently, learning workshops as a creative tourist activity—focused on unique experiences—were recognized. However, destinations also implemented marketing management strategies that closely resembled those of other destinations within the network.

Table 2 – Characteristics of the destinations belonging to the observed networks

|

Analytical Categories |

Definition |

Characteristics of destinations belonging to networks |

Discussion |

|

External environment |

Recognized as all external pressures exerted on an institution and that have a direct and indirect influence on organizational development. |

|

Having more actors in projects as a tourist destination means that there is greater pressure through these new actors. Stakeholders influence both your decisions in the organization and your practices. |

|

Analytical Categories |

Definition |

Characteristics of destinations belonging to networks |

Discussion |

|

Relationship with other organizations |

Relationships maintained by an organization based on an end and which allow it to cooperate based on a common objective. |

|

The relationship with other organizations in these actors can be understood to the extent that together they opt for specific services such as academics, monitoring and training that can be decisive in the practices of the actors as a tourist destination. |

|

Regulatory and regulatory frameworks |

All mechanisms recognized as norms or regulations that enable organizations to control their inter-institutional relations. |

|

The regulatory frameworks recognize all the activities and projects to which destinations are being exposed because they belong to cooperation networks. |

|

Isomorphism |

A trait that indicates a shared feature in an institution‘s organisational practices, observable through its interactions with other institutions. |

|

Actors are influenced in practices that are not very differentiated, as well as a similarity in creative tourism experiences such as courses, workshops: and as an organization they also have a lot of similarity in the use of social networks, city branding, similar marketing strategies. |

Source: Prepared by the authors

-

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This empirical study offers a different perspective on creative tourism compared to what the existing literature has traditionally covered for tourist destinations. Although the tourism market niche is presented as a development opportunity, it helps us to analyze the practices of tourist destinations that have already incorporated creative experiences and are part of specialized cooperation networks. Studying these practices allows us to see how creative tourism has become established in these destinations, which hold a clear advantage over those just starting to explore creative tourism through their practices.

Creative tourism, as a modern phenomenon, has evolved conceptually through the development of its practices from various theoretical views. As a niche within the experience economy, destinations play a crucial role in creating satisfying tourist experiences, as tourists engage with the destination’s physical environment while participating in these activities.

Tourist centres are analyzed from an organizational standpoint, shaped not only by the rise of creative tourism – prompting them to create environments for creative experiences – but also by their efforts to position themselves as destinations embracing modern practices. To do so, they often collaborate with other stakeholders, seeking to gather more information, enhance their visibility, and obtain advice and mentoring. This collaborative approach helps them leverage creativity as a key driver of development within their structures.

This cooperation networks focused on creative tourism help us understand the features of this phenomenon in tourist destinations, which are key players and thus have a significant role. Practices developed in tourist centers through network cooperation exhibit specific characteristics, such as the emergence of the phenomenon from a global level down to local contexts. This approach enables destinations to be held accountable for adopting tourism practices that promote destination development without causing collateral problems. It also supports the destination’s socio-economic growth through inherent cultural resources, materialized in authentic experiences.

Through network cooperation, institutions are guided by rules and obligations linked to common objectives. These entities collaborate to understand how to strengthen creative tourism beyond just a market niche in the tourism industry. This involves solidifying both the destination’s management, planning, and establishment of guarantees for these experiences, as well as promoting a tourist offer that leverages this niche to meet the needs and motivations of new tourists.

The similarity between the marketing strategies of tourist destinations and creative cities is acknowledged. They often involve city brands linked to creative tourism, such as Barcelona Creativa, Loulé Creativa, Biot La créative, Io sono Friuli Venezia Giulia, Tourisme Iles de la Madeleine, Quito Creative Friendly Destination, Gabrovo City of Crafts and Folk Arts, PTI Creative Destination, Katowice Misasto Muzyky UNESCO, Queretaro Creativo, and Québec Ville de Littérature UNESCO. These initiatives frequently utilize websites and social media platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter to promote their projects as creative destinations or cities.

A limitation of the study is the need for more in-depth research from the perspective of tourist destinations, in order to continue attracting the sector’s governance attention towards developing practices aligned with what current tourists are consuming. Furthermore, an appeal is made to the global tourism sector to continue creating tourist experiences that are grounded in the realities of the destinations. However, it is suggested that the scientific community continue to contribute from their side, with an understanding of these emerging phenomena that are seen as opportunities for tourist centres. Finally, tourism decision-makers are encouraged to consider each characteristic of these cooperation networks, which can help them gain competitive advantages that are highly beneficial for their destinations.

Список литературы Creative Tourism Through Cooperation Networks: Balancing Uniqueness and Commonality. Insights From Institutional Theory

- 1. Barrera-Fernandez, F., & Hernandez-Escampa, M. (2017). From cultural to creative tourism: urban and social perspectives from Oaxaca, México. Revista de Turismo Contemporâneo, 5.

- 2. Booyens, I., & Rogerson, C. M. (2015). Creative Tourism in Cape Town: An innovation perspective. Urban Forum, 26(4), 405-424. doi:10.1007/s12132-015-9251-y

- 3. Caballero Míguez, G. (2007). Nuevo institucionalismo en ciencia política, institucionalismo de elección racional y análisis político de costes de transacción: una primera aproximación. Revista de investigaciones políticas y sociológicas, 6(2), 9-27.

- 4. Creative Tourism Network. (2014). Creative Tourism Network. URL: http://creativetourismnetwork.org

- 5. De Bruin, A., & Jelinčić, D. A. (2016). Toward extending creative tourism: participatory experience tourism. Tourism Review, 71(1), 57-66.

- 6. Dimaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. London: Sage.

- 7. Duxbury, N., & Richard, G. (2019). Towards a research agenda for creative tourism: developments, diversity, and dynamics. A research agenda for creative tourism. Edward Elgar Publ., 1-14.

- 8. Hall, P., & Taylor, R. (1996). Political Science and the Three New Institutionalism. Political Studies, 44(5), 936-957.

- 9. Herrera-Medina, E., Bonilla-Estévez, H., & Molina-Prieto, L. (2013). Ciudades creativas: ¿paradigma económico para el diseño y la planeación urbana? Bitacora, 22(1), 11-20.

- 10. Ibañez, R., & Cabrera, C. (2011). Teoría General del Turismo: un enfoque global y nacional. Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur. Serie Didáctica. URL: https://dspace.itsjapon.edu.ec/jspui/bitstream/123456789/337/1/teoria%20general%20del%20turismo.pdf.

- 11. Maitland, R. (2010). Everyday life as a creative experience in cities. International Journal of culture, tourism and hospitality research, 4(3), 176-185.

- 12. Molina, S. (2016). Turismo creativo. Turismo: Estudos & Práticas (RTEP/UERN), 5(1), 205-223.

- 13. Nash, D. (1989). Tourism as form of imperalism. In V. Smith, Hosts and guest (The Antropology of tourism). University of Pennsylvania Press, 37-52.

- 14. Organização do Turismo (UNWTO). (2020). World Tourism Barometer, 18(5).

- 15. Ovalles, M. (2017). Nuevas formas de viajar: “El turismo creativo”: Tesis de grado. San Cristobal de la Laguna: Universidad de la Laguna.

- 16. Paretl, S., & García, B. (2020). Barrio Matadero-Franklin, de mercado popular a barrio artístico-cultural. Conservación y capitalización, a través de turismo creativo y cocreación. Architecture, city and Enviroment, 15(45), 1-16.

- 17. Pérez-Ramirez, R. (2019). Administración pública y gobernanza en México. Análisis del cambio institucional en la agenda de buen gobierno. Estado de México: ECORGAN-México.

- 18. Peters, G. (1999). Institutional Theory in political science: The new institutionalism. Routledge.

- 19. Picco, M. (2019). Marketing urbano, ciudades creativas y turismo. Análisis turístico de las transformaciones urbanas en la ciudad de Santa Fe, Provincia de Santa Fe, Argentina, desde el año 2004 hasta el 2017. Realidad. Tendencias y desafios en Turismo (condet), 17(2), 105-133.

- 20. Picornell, C. (1993). Impactos del turismo. Papers de turisme, 11, 65-91.

- 21. Richards, G., & Marques, L. (2012). Exploring Creative Tourism: Editors Introduction. Journal of Tourism Consumption and Practice, 4(2), 1-11.

- 22. Richards, G., & Raymond, C. (2000). Creative Tourism. Atlas news, 23, 16-20.

- 23. Richards, G., & Wilson, J. (2006). Developing creativity in tourist experiences: A solution to the serial reproduction of culture? Tourism management, 27(6), 1209-1223.

- 24. Rivera Mateos, M. (2013). El turismo experiencial como forma de turismo responsable e intercultural. Relaciones interculturales en la diversidad: Cátedra Intercultural, 199-217.

- 25. Rosero, X., & Restrepo, M. (2002). Teoría institucional y proceso de internacionalización de las empresas colombianas. Estudios gerenciales, 18(84), 103-123.

- 26. Rubí-González, F., & Palafox-Muñoz, A. (2017). El turismo como catalizador de la pobreza. Trabajo turístico y precariedad en Cozumel, México. Barcelona: Alba Sud Editorial.

- 27. Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and Organizations. Ideas, Interests and Identities. Management, 17, 136.

- 28. Solórzano, G. (2015). Ciudades creativas y patrimonio cultural: nuevos escenarios para la conservación del patrimonio en México. Repositorio ITESO, 159-179.

- 29. UNESCO. (2021). Creative Cities Network. URL: https://es.unesco.org/creative-cities/content/ciudades-creativas.

- 30. Vargas, J. (2008). Teoría Institucional y neoinstitucional en la administración internacional de las organizaciones. Revista cientifica “visión de futuro”, 10(2).