Cultural interaction patterns in the Bronze Age: ritual bronze artifacts from Korea and Japan

Автор: Nesterkina A.L., Solovieva E.A., Gnezdilova I.S.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145448

IDR: 145145448 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.3.068-073

Текст статьи Cultural interaction patterns in the Bronze Age: ritual bronze artifacts from Korea and Japan

The Bronze Age was an important period in the history of the peoples who lived in East Asia. At this time, first metal (bronze) items appeared in the cultures of the region. Tools and implements made from stone and bone continued to be used for household needs; their manufacturing techniques continued to be improved, and their typological composition expanded. Bronze items were not widely used in all areas of life in the society. Prestigious and ceremonial paraphernalia, such as weaponry, jewelry, etc., were made from bronze. Owing to their distinctive appearance, non-utilitarian bronze items serve as ethnic and cultural markers, making it possible to establish migration routes for individual human groups and ways of cultural exchange.

The beginning of wide proliferation of bronze ritual items on the Korean Peninsula is closely related to the so-called culture of narrow-bladed bronze daggers or the culture of Korean-type daggers (4th–1st centuries BC) (Lee Chong-gyu, 2007: 120–124). Its initial center was located in the territory of Wiman Joseon in the basin of the Taedong River in northwestern Korea (Butin, 1982: 259); but gradually narrow-bladed daggers and other ritual bronze items spread to the south of the peninsula, mainly to the basins of the Geumgang River (Chungcheongnam-do province) and Yeongsangang River (Jeollanam-do province) (Hanguksa, 1997: 61). Over time, ritual items of the culture of narrow-bladed daggers began to be used in other parts of the East Asian region. Certain items of this category have been found in the Russian Primorye (Okladnikov, Shavkunov, 1960: 283; Kang In-uk, Cheon Seon-haeng, 2003: 6–8). A relatively large amount of evidence associated with Korean-type bronze ritual items has been found in Japan. Bronze ritual items are the unique sources of information on the early contacts of the population inhabiting the Korean Peninsula with the Japanese Islands.

Bronze ritual items in Korea

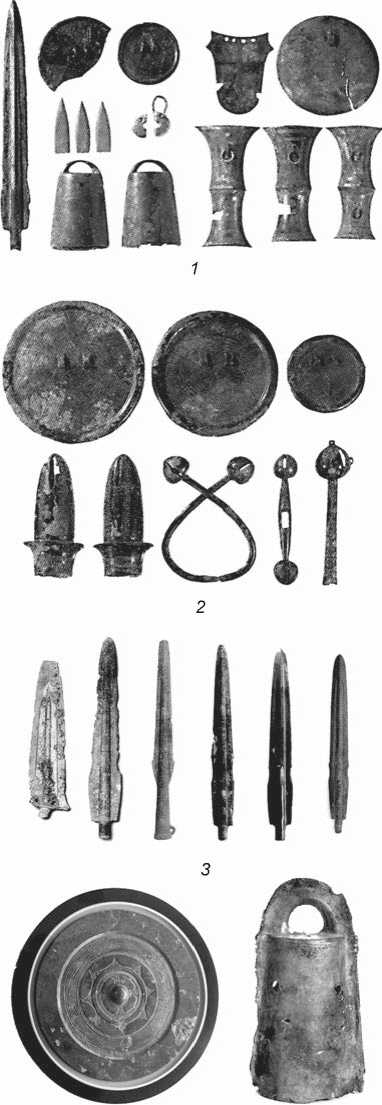

Early sites with bronze ritual items (4th to 3rd centuries BC) in South Korea have been discovered in the basin of the Geumgang River. One of these sites ( Goejeong-dong ) has been discovered within the boundaries of Daejeon city during land-surveying, and was investigated by the team from the National Museum of the Republic of Korea in 1967. The site is a partially destroyed single burial; a stone box measuring 2.2 × 0.5 × 1.0 m in size was composed of amorphous rock debris, and was located in a funnelshaped soil pit (2.5 × 0.73 × 2.7 m). The stone structures of the bottom and cover have not been found. The upper part of the pit filling was made up of rock fragments— possibly, the remains of a structure above the grave that might have been a stone mound. Wood decay (probably, the remains of wooden coffin) has been found at the bottom of the burial. The burial goods of the complex included pottery and items of bronze and stone (see Fig. 1). The pottery complex consisted of a vase-like vessel with a black polished surface, and a pot-like vessel with round pasted band on the rim. Ritual bronze artifacts were represented by a narrow-bladed dagger, decorative handle onlays (3 spec.), bells (2 spec.), gong, mirrors with thick linear geometric ornaments (2 spec.), and a shieldlike item. Three stone arrowheads and two jade kogok ( magatama ) pendants have also been found (Yi Un-chang, 1968: 76–91).

Inventory complexes of similar composition have been discovered at Namsong-ri and Dongseo-ri sites.

The Namsong-ri site near Asan city was discovered during construction work in 1976 and was examined by the team from the National Museum of the Republic of Korea. A burial in the form of a stone box made of flagstone (2.8 × 0.8–0.9 × 0.7 m), which was built in a funnel-shaped soil pit (the size in the upper part was 3.1 × 1.8 m; depth was 2 m), was found at the site. Large number of stones that could have composed the mound was found in the upper part of the pit filling. Wood decay (the remains of a coffin) was found in the filling of the stone box. The grave goods included ritual bronze items: narrow-bladed daggers (9 spec.), shield-like item, decorative handle onlays (3 spec.)— one of them depicted a roe deer, and mirror with thick linear ornament (2 spec.). A bronze celt-axe, chisel, jade kogak pendant, and 103 tubular beads were also found at the site (Han Byeong-sam, Lee Geon-mu, 1977: 6–14).

The Dongseo-ri site was discovered in 1978 during construction work near Yesan city. It is not possible to determine the layout and exact size of the site owing to its severe damage. According to indirect features, it was most likely a stone box with an earthen floor, and without an additional cover. Judging by the large number of rock fragments, the burial had a stone mound. The set of the

Goods of the burial from Goejong-dong (Republic of Korea) (Lee Chong-gyu, 2007) ( 1 ); goods of the burial from Chopo-ri (Republic of Korea) (Ibid.) ( 2 ); ritual weapons from the sites in northern Kyushu Island (Japan) (Itokoku rekishihakubutsukan, 2012) ( 3 ); bronze mirror from the Hirabaru cemetery (Fukuoka prefecture, Japan, collection of the Itoshima Historical Museum) (Ibid.) ( 4 ); dotaku bronze bell from Hatsukayama (Nara prefecture) (The Museum…, 2012) ( 5 ).

grave goods included bronze ritual items, jade beads (126 spec.), stone polished arrowheads (5 spec.), vaselike vessel with black polished surface, and fragments of a vessel with rounded pasted band on the rim. Ritual bronze items included narrow-bladed daggers (9 spec.), decorative handle onlays (3 spec.), a pipe-shaped item (presumably a part of the headdress of the buried person’s), mirrors with thick and thin linear ornaments, and a gong (Ji Gon-gil, 1978: 153–161).

More sophisticated complexes with bronze ritual items have been found at the Daegok-ri and Chopo-ri sites (3rd to 2nd centuries BC), in the basin of the Yonsangan River.

The Daegok-ri site was discovered in 1971 during construction work. The site was a burial in a stepped earthen pit. The size of the pit at its upper part was 3.3 × 1.8 × 0.85 m, and at the floor level 2.1 × 0.8 × × 0.6 m. A massive fragment of a wooden item measuring 0.9 × 0.45 m (probably the remains of coffin) was found in the eastern part of the pit. The set of the grave goods included ritual bronze artifacts: narrow-bladed daggers (3 spec.), mirrors with thin linear ornaments (2 spec.), and 2- and 8-pointed bells (4 spec.). A bronze celt-axe and chisel were also found there (Cho Hyun-jong, Jang Je-geun, 1996: 567–571).

The Chopo-ri site was discovered in 1987 during construction work in one of the villages in Hampyeong County. The team from the Gwangju National Museum carried out archaeological rescue works at the site. It was found out that the site was a burial in a funnelshaped earthen pit (2.6 × 0.9 m) with stone box (1.9 × 0.55 × 0.55 m). Wood decay (presumably, the remains of wooden coffin) was discovered on the floor of the burial. Judging by large number of stone fragments in the filling of the pit, it used to be a mound over the burial. The set of the grave goods consisted of 26 items (see Fig. 2). The category of ritual bronze items included narrow-bladed daggers with decorative pommels (2 spec.), a Chinese-type dagger with a tosyg handle, picks (3 spec.), a socketed spearhead, a bell-shaped scepter pommel; 1-, 2- and 8-pointed bells (3 spec.), and mirrors with thin linear ornaments (3 spec.) have been found. A bronze celt-axe, a mortise chisel, and two chisels were also found in the burial (Ibid.: 571–577).

The Hapsong-ri site was discovered in 1989 during plowing of the territory for planting crops in Buyeo County of the Chungcheongnam-do province. Archaeological rescue works were carried out at the site by the team from the Buyeo National Museum, but it was not possible to find out the details of its structure during these works, since the item was almost completely destroyed. According to the researchers, the item was a single burial in a wooden coffin or earthen pit without additional structures, covered by stone mound. The set of ritual bronze items gathered during the rescue operations included narrow-bladed daggers (2 spec.), a pick, bells (2 spec.), fragments of a disk-shaped item, fragments of mirror with geometric ornament made in thin lines, and an item of unclear function, which looked like votive pick. The goods associated with the site also included two iron celt-axes, a chisel, fragments of black polished pottery, and eight tubular jade beads (Lee Geon-mu, 1990: 25–30).

In recent years, several more sites with ritual bronze artifacts have been discovered on the Korean Peninsula. In 2014–2015, during archaeological rescue excavations at the site of Hoam-dong, located in the boundaries of Chungju city in the Chungcheong-bukto province, the Central Korean Cultural Heritage Center investigated three burials. One of those burials that contained the largest amount of grave goods was a funnel-shaped earthen pit measuring 1.75 × 0.82 m, 1.75 m deep. Wood decay found on its floor indicated the presence of a wooden coffin, which used to be in the pit. Given the numerous fragments of stone in the filling of the pit, it can be assumed that a mound used to cover the burial. Burial goods consisted of ritual bronze items: narrow-bladed daggers (7 spec.), a mirror with thin linear ornament, a pick, socketed spearheads (3 spec.), and bronze working tools, such as a celt-axe, mortise chisels (4 spec.), and chisels (2 spec.), as well as a vessel with a polished black surface, and fragment of a porcelain item (Kim Moo-joong et al., 2017: 35–67).

In 2015, the team from the Buyeo National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, studied the Cheongsong-ri site in Buyeo County of the Chungcheong-bukto province. It was found out that the site was a heavily destroyed single burial in an earthen pit (at the time of the study, the size was 1.64 × 0.8 × 0.2 m), possibly with a wooden coffin. There was no stone mound above or around the burial; however, three pieces of limestone, located near one wall of the pit, suggest its presence. The floor of the pit did not have additional structures. Artifacts made from bronze, jade, and stone (31 spec.) were found in and beyond the burial. The set of ritual bronze items included a narrow-bladed dagger, decorative pommels of daggers (2 spec.), socketed spearheads (4 spec.), a mirror with thin linear ornament, and the scepter pommel. The grave goods also contained bronze tools (celt-axe, mortise chisel, and two chisels), jewelry (14 jade tubular beads), and four stone arrowheads (Lee Ju-heon et al., 2017: 44–45, 58–96, 112–130, 141–181).

Thus, the complex of ritual bronze artifacts found on the Korean Peninsula can be divided into two groups: the first includes weaponry and accompanying items (narrow-bladed daggers, socketed spears, picks, handle onlays), and the second includes ritual paraphernalia and elements of the outfit (mirrors, gongs, bells, small bells, shield-like items, pipe-shaped items, and staff pommels). All artifacts are associated with single burials of sophisticated structure in deep stepped earthen pits with a wooden coffin and stone mound. Judging by the design of the burial and composition of the funeral goods, such burials were intended for people who had a high social status and played an important role in the community rituals.

Bronze ritual items in Japan

The earliest bronze ritual items in Japan, called “Korean-type items”, have been found in the north of Kyushu Island. The time of their appearance there corresponds to the late early to early middle stages of Yayoi period (mid 3rd century BC). The finds from burial 3 at the cemetery of Yoshitake-Takaki in Fukuoka prefecture are of interest to our overview. A large number of burials in pottery vessels and wooden coffins have been found in the flat-grave burial ground that was a part of the Iimori complex. Such a combination of burial structures was typical for this period. Burial 3 was a burial in an earthen pit with a wooden coffin. It contained the richest grave goods complex, including two bronze narrow-bladed daggers, a pick, a socketed spearhead, a mirror with thin linear ornament, a jade magatama pendant, and 95 tubular jasper beads (Yoshitake-takaki, 1986: 8). According to K. Mizoguchi, the person buried in the grave had a special status, since the grave goods of the burial differed from the grave goods found in other graves. A mirror and numerous beads, which probably used to be assembled into a necklace, can be considered to be the markers of religious authority, while several weapons indicate community leadership or community authority (Mizoguchi Koji, 2002: 154). During the Yayoi period, many areas of life were ritualized. If during Jomon period the main reflection of ritual content was pottery, in Yayoi period these were metal items, primarily made from bronze.

The same set of items (bronze narrow-bladed daggers, socketed spearheads, mirrors with thin linear ornaments, and jade magatama pendants), as from burial 3, was found in burials in pottery vessels at the Uki-Kunden cemetery in Saga prefecture (Hanguksa, 1997: 314–315). The scholars attributed the site to Middle Yayoi period (The Cambridge History…, 1993: 275). Korean-made bronze swords were found at the Okamoto-cho and Kasuga sites in Fukuoka prefecture, and Yasunagata and Tosu in Saga prefecture.

According to some scholars, a set consisting of a bronze mirror, a dagger or a sword, and magatama pendants, which appeared in some burials, is similar in its composition to the “three regalia” symbols of power, which appeared later (Ibid.: 274). Since these burials were attributed to the time of the emerging state entities and struggle for power, when several political centers existed in Kyushu and southwestern Honshu, we may assume that this set of items could have been the sign of the emerging special symbols—ritual attributes. Mirror, sword, and jasper pendants as a symbol of the imperial power are mentioned in “Nihonshoki”—one of the earliest written sources: the goddess Amaterasu gave them to her grandson and first emperor Ninigi-no-mikoto when he was sent to Earth (Nihonshoki, 1997: 128). Subsequently, the mirror became the most important sacred item of the Ise Shrine—the main temple of goddess Amaterasu; the sword became the sacred item of the Atsugi Shrine, and jasper pendants were considered to be the talismans of the Imperial House.

Bronze ritual items found at the early sites of Kyushu Island reveal both similarities and significant differences with their Korean prototypes. On the Korean Peninsula, bronze narrow-bladed weapons are unknown in the burials in pottery vessels. In Japan, the Korean-type bronze items have been found both in burials with wooden coffins, typical of the Korean Peninsula, and in the burials in urns which are the predominant type of burial. The grave goods with bronze ritual items at the Japanese sites included narrow-bladed daggers, picks, socketed spearheads, and mirrors with thin linear ornaments (see Fig. 3). Bells, small bells, and scepter pommels, which appeared at the Korean sites, were absent from the sites of the Early Yayoi period.

Casting-moulds for manufacturing bronze narrow-bladed daggers have been found at the Katsuma and Otani sites in Fukuoka prefecture, and Soza in Saga prefecture; also socketed spearheads at the Soza and Yoshitake-Takaki sites in Fukuoka prefecture, and picks at the Nabeshima site in Saga prefecture. These finds indicate that the center of bronze casting, specialized in manufacturing the items of the Korean type, emerged on Kyushu Island (Hanguksa, 1997: 314). Thus, early cultural contacts between the populations of Korea and Japan in the Bronze Age were manifested not only by migrations and direct borrowing of individual elements of culture, but also by borrowing new technologies.

Further transformation of bronze daggers and spearheads of the Korean type in Japan was associated with the increased size and width of the blade. This might have served the purpose of their improvement as ritual and ceremonial items (Jo Jin-seon, 2016: 136). It should be mentioned that narrow-bladed weaponry in Korea was also a part of the category of ritual items, but their proportions did not change over time. With morphological changes, the role of these items in the ritual might have been transformed, and they started to occur not only in burials, but also in hoards (Miyazato Osamu, 2012: 3).

At the beginning of the Late Yayoi period, the complex of ritual bronze items at the Japanese sites included mirrors not of the Korean, but of the Han type. One of the most famous and important locations of bronze mirrors is the Hirabaru site in the north of Kyushu Island (see Fig. 4) (Harada Dairoku…, 2011: 34). A large number of goods, particularly bronze mirrors and magatama beads, were found in the burial chamber of burial mound No. 1. Forty mirrors were reconstructed from the fragments; the largest mirror reached 46.5 cm in diameter and weighted about 8 kg (Itokoku rekisihakubutsukan, 2012: 26). Some of the mirrors were Chinese imported products; the others were produced locally. Thus, the Korean prototypes of mirrors were apparently replaced by more prestigious Chinese (Han) prototypes.

Bells became most widespread since the Middle to Late Yayoi period in Japan among bronze ritual items of the Korean origin. The conditions of discovering dotaku bells, as well as variety of their sizes and decorative elements, make it possible to conclude that they must have had their own ritual function unrelated to funeral practices (see Fig. 5). Dotaku bells most often occurred individually or as “hoards”—clusters of several dozen bells, located outside the settlements and not accompanied by any structures.

Conclusions

The study of ritual bronze items found on the sites of the Bronze Age in Korea and Japan (4th century BC to 3rd century AD) identified the main stages and forms of interaction between the two cultures in the period under consideration. In the early stage of the Bronze Age, bronze items in Korea and Japan were closely related to the funeral rite, since the finds occurred in single burials. Such burials might have belonged to the people of high social status. The great similarity between the evidence and geographical proximity of their areas of distribution suggests that some groups of population would migrate from the southwestern part of the Korean Peninsula to the west of the Japanese archipelago at the time under consideration. These movements seem to have contributed to the transition of new technologies. The technology of manufacturing bronze ritual items developed on its own in Japan. New forms of products were created there on the basis of Korean and later Chinese prototypes. The role of these items in ritual practices also changed: their association with the funeral rite and the individual social status of the buried person gradually changed, and, on the contrary, their importance in community rituals and cults increased.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Project No. 18-09-00507).