Cuneiform tablet Plimpton 322 and Pythagorean triples in ancient Babylon

Автор: Andrei Shchetnikov

Журнал: Schole. Философское антиковедение и классическая традиция @classics-nsu-schole

Рубрика: Статьи

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.20, 2026 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article proposes a new reconstruction of the ancient Babylonian cuneiform tablet Plimpton 322, containing 15 Pythagorean triples. This reconstruction is based on a sequential listing of sexagesimal fractions that have a finite number of digits and lie within the specified interval.

Old Babylonian mathematics, Pythagorean triples, Plimpton 322

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147252942

IDR: 147252942 | DOI: 10.25205/1995-4328-2026-20-1-189-199

Текст научной статьи Cuneiform tablet Plimpton 322 and Pythagorean triples in ancient Babylon

Cuneiform tablet Plimpton 322

The Babylonian cuneiform tablet Plimpton 322 is housed in the Plimpton Collection at Columbia University in New York City. George Arthur Plimpton, who donated his collection to the university in the mid-1930s, received the tablet from archaeologist Edgar J. Banks in 1922. According to Banks, the tablet was found during

excavations at the ancient city of Larsa in southern Mesopotamia. It was composed around 1800 BC, during the Hammurabi dynasty, as determined by the nature of the cuneiform writing and by its similarity to other economic tablets found near Larsa. A break on the left and traces of glue on it indicate that this tablet had a left side, which was lost after the excavations. The surviving part of the tablet measures approximately 13 cm wide, 9 cm high, and 2 cm thick.

The Plimpton 322 tablet was published by Neugebauer & Sachs 1945 and was analyzed in varying detail by Neugebauer 1951, Bruins 1949 et al., Weiman 1961, Price 1964, Raik 1967, Buck 1980, Friberg 1981. Subsequent publications on this tablet are also quite extensive; see the reference list at the end of the article.

Preliminary data analysis

The tablet contains numbers written in the sexagesimal notation in four columns and fifteen rows. The right-hand column contains the row numbers 1 through 15. The left-hand column will be discussed below; we will begin our discussion of the numerical data in the tablet with the two middle columns. Otto Neugebauer, who was the first to examine the tablet, showed that the middle columns contain numbers that are part of Pythagorean triples: the “height number” in the second column and the “hypotenuse number” in the third column. Based on this, he corrected four numbers that were written with errors. These numbers are written below in corrected form and are highlighted in italics. Since the sexagesimal notation is unfamiliar to us, all these numbers are duplicated in decimal notation. The two columns from the cuneiform tablet are supplemented here by another column with “base number” a, such that a 2 = c 2 – b 2.

|

sexagesimal notation |

decimal notation |

||||

|

b |

c |

a |

b |

c |

|

|

1,59 |

2,49 |

120 |

119 |

169 |

|

|

56,7 |

1,20,25 |

3456 |

3367 |

4825 |

|

|

1,16,41 |

1,50,49 |

4800 |

4601 |

6649 |

|

|

3,31,49 |

5,9,1 |

13500 |

12709 |

18541 |

|

|

1,5 |

1,37 |

72 |

65 |

97 |

|

|

5,19 |

8,1 |

360 |

319 |

481 |

|

|

38,11 |

59,1 |

2700 |

2291 |

3541 |

|

|

13,19 |

20,49 |

960 |

799 |

1249 |

|

|

8,1 |

12,49 |

600 |

481 |

769 |

|

|

1,22,41 |

2,16,1 |

6480 |

4961 |

8161 |

|

|

45 |

1,15 |

60 |

45 |

75 |

|

|

27,59 |

48,49 |

2400 |

1679 |

2929 |

|

|

2,41 |

4,49 |

240 |

161 |

289 |

|

|

29,31 |

53,49 |

2700 |

1771 |

3229 |

|

|

56 |

1,46 |

90 |

56 |

106 |

|

A direct examination of this table reveals the following facts:

-

1) The numbers in the Pythagorean triples in all rows except two are coprime. The numbers (75, 45, 60) in the 11th row are divisible by 15 to the coprime triple (5, 3, 4). The numbers (106, 56, 90) in the 15th row are divisible by 2 to the coprime triple (53, 28, 45).

-

2) All the “base numbers” except three are divisible by 60. The number 90 in the 15th row is divisible by 30, and the numbers 3456 in the 2nd row and 72 in the 5th row are divisible by 12.

-

3) Although the triples in the table at first glance are arranged disorderly, there is a certain order in their arrangement. This is indicated by the first column of the tablet, which contains the squared ratio of the hypotenuse to the base (or the squared ratio of the height to the base, which is one less). These squares decrease from top to bottom, from 1;59,0,15 = 1.983… in the 1st row to 1;23,13,46,40 = 1.387… in the 15th row.

-

4) The triple (169, 119, 120) in the 1st row, whose legs differ by one, defines a right triangle whose height is slightly less than the base. In the following triangles, the angle between the hypotenuse and the base successively decreases, reaching an angle slightly less than 32°.

Of course, the two main questions about Plimpton 322 are (1) how were these Pythagorean triples obtained, and (2) why are these particular triples, and no others, written here? These are the questions we will try to answer below.

The Pythagorean Theorem

Since Plimpton 322 lists Pythagorean triples, we begin our analysis with the Pythagorean Theorem. The fact that in any right triangle the sum of the squares of the legs is equal to the square of the hypotenuse was certainly known to Babylonian mathematicians of this era. However, not a single tablet with a drawing demonstrating this theorem has come down to us. It seems that demonstrative reasoning in ancient Babylon was transmitted orally from teacher to his pupils and was not intended to be recorded.

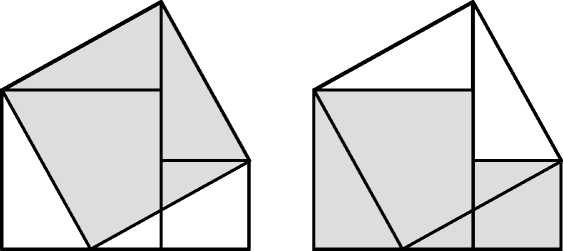

The simplest proof of the Pythagorean Theorem is based on the following drawing. Thу whole figure is composed here of two right-angled triangles and the square of its hypotenuse; but in another tessellation this figure is composed of the same right-angled triangles and the squares of both legs, which proves the theorem.

General formula for Pythagorean triples

Now we will apply to the sides of a right triangle a general method known to Babylonian mathematicians for solving problems in which the area of a rectangle and the sum or the difference of its two sides are given. This method consists of representing two quantities c > b as the sum and the difference of two other quantities, с = p + q , b = p – q .

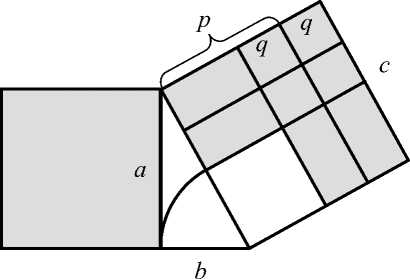

Let c be the hypotenuse of a right triangle, and b one of its legs. Then the square of the other leg a can be represented as a 2 = c 2 – b 2 = 4 pq , which is shown in the following figure.

The next fundamental Babylonian idea is to set a = 1. In the Babylonian sexagesimal notation, 1 simultaneously is 60, 3600, etc., and in the opposite direction, it is 1/60, 1/3600, etc., which we will also use.

Since a 2 = 4 pq = 1, the numbers 2 p and 2 q are reciprocal. Historians of Babylonian mathematics usually used the relation 2 q = 1/(2 p ), but the numbers p and 4 q = 1/(4 p ) are also reciprocal, and in this reconstruction we will express the hypotenuse c and the leg b through their arithmetic mean p in the following way:

с = p + 1/(4p), b = p – 1/(4p).

Another problem leading to Pythagorean triples

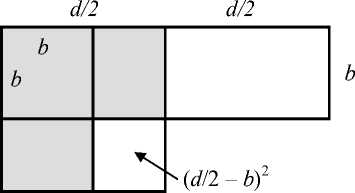

Let ab = S , a – b = d be given. To find the sides a and b , the segment b is applied to a , their difference d is divided in half. Now the rectangle is transferred to the gnomon, which is completed to a square. The area of this square is S + ( d /2)2, and it is also equal to ( b + d /2)2.

|

b |

d S |

a

|

b |

d /2 |

d /2 |

|

( d /2) 2 |

Denoting b + d /2 = p , we obtain the equation S + ( d /2)2 = p 2. Pythagorean triples are connected with this equation if the area S is the area of some square with integer sides.

Now let ab = S , a + b = d be given. To find the sides a and b , the segment b is set aside from a , their sum d is divided in half; the rectangle is transferred to the gnomon, which is completed to a square. The area of this square is S + ( d /2 – b )2, and it is also equal to d 2. Denoting d /2 – b = p , we obtain the equation S + p 2 = ( d /2)2.

d

a

S

In Babylonian mathematical tradition, the area S usually is taken as 1 (or, equivalently, as 60, 602, etc.). In this case, the sides a and b are reciprocal numbers, and the problem was formulated as follows: “The difference or the sum of two reciprocal numbers is equal to d , find them.”

Regular reciprocal numbers

In Babylonian arithmetic, pairs of reciprocal numbers were considered regular , if both numbers had a finite sexagesimal notation. Many tablets with lists of such regular pairs have come down to us, and their standard beginning looks like this:

|

2 |

30 |

16 |

3,45 |

45 |

1,20 |

|

3 |

20 |

18 |

3,20 |

48 |

1,15 |

|

4 |

15 |

20 |

3 |

50 |

1,12 |

|

5 |

12 |

24 |

2,30 |

54 |

1,6,40 |

|

6 |

10 |

25 |

2,24 |

1 |

1 |

|

8 |

7,30 |

27 |

2,13,20 |

1,04 |

0,56,15 |

|

9 |

6,40 |

30 |

2 |

1,12 |

0,50 |

|

10 |

6 |

32 |

1,52,30 |

1,15 |

0,48 |

|

12 |

5 |

36 |

1,40 |

1,20 |

0,45 |

|

15 |

4 |

40 |

1,30 |

1,21 |

0,44,26,40 |

Such a table is used primarily for dividing one number by another. For example, to divide a number by 25, it is multiplied by 2.24, the reciprocal of 25 (that is, by 2/60 + 24/602, or, what is the same, by 2 · 60 + 24, you just need to correctly separate the integer digits from the fractional ones, which is done orally, not in writing).

In relation to the construction of Pythagorean triples, the condition of regularity of reciprocals means that the numerator and denominator of p in its factorization must contain only powers of 2, 3, 5, which are prime divisors of 60. For the irreducible fraction an additional condition arises: if one of the numbers 2, 3, 5 is in the divisor of the numerator, this number must not be the divisor of the denominator, and vice versa.

Now we represent p as a simple fraction p = m / n and again turn to the formulas expressing the hypotenuse с and the leg b of the right triangle through their arithmetic mean p (when the other leg a =1):

с = p + 1/(4p) = m/n + n/(4m) = (4m2 + n2)/4mn, b = p – 1/(4p) = m/n – n/(4m) = (4m2 – n2)/4mn.

If we want the numbers in the Pythagorean triple to be integers, we need to increase them by 4 mn times:

с = 4 m 2 + n 2, b = 4 m 2 – n 2, a = 4 mn .

If n is an odd number, this triple will be coprime, for m and n are coprime initially. If n is an even number, then m is an odd number, and the numbers in this triple can be reduced by 4.

Here it should be emphasized that Babylonian mathematicians did not use simple fractions and performed all their calculations in sexagesimal notation. However, if p is a regular sexagesimal number, the reduction of the triplet to an irreducible form can be performed with such calculations too, which requires some skill in handling sexagesimal numbers.

Key row of the table

Now we will construct on this basis all the Pythagorean triples listed in the Babylonian tablet. It is natural to start with the simplest case and set p = 1. In this case we get c = 5/4 and b = 3/4, which gives the Pythagorean triple (5, 3, 4).

However, the “Babylonian” reasoning in this case will be trickier. Let p = 1 = 60/60; then q = 1/4 = 15/60. Then, by addition and subtraction, we find c = 75/60 and b = 45/60. This leads to the Pythagorean triple (75, 45, 60), which stand in the 11th row of the Babylonian tablet.

This row divides the table into upper and lower parts, and we will look at them separately.

The upper part of the table

Let p = 6/5; then q = 5/24. We reduce both fractions to a common denominator and obtain p = 144/120, q = 25/120. Hence c = 169/120, b = 119/120. This leads to the Pythagorean triple (169, 119, 120), defining a right triangle close to half a square.

Next, we will list the Pythagorean triples satisfied the condition 1 < p ≤ 6/5, according to the following rule. First of all, we write out the numbers composed of the factors 2, 3, 5, in ascending order:

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 16, 18, 20, 24, 25, 30, 32, 36, 40, 45, 48, 50, 60, 64, 72, 75, 80, 81, 90, 96, 100, 108, 120, 125, 128, 135, 144, …

Taking these numbers as possible numerators of p , we find denominators from the same sequence which satisfied the condition 1 < p ≤ 6/5, where the simple fraction p is irreducible. The first ten terms of this sequence are

6/5, 9/8, 10/9, 16/15, 25/24, 27/25, 32/27, 75/64, 81/80, 125/108.

The next fractions are 128/125, 135/128, 144/125, …; however, the author of the tablet stops at 125/108, as we will see below.

Now let’s arrange these ten fractions in descending order:

6/5, 32/27, 75/64, 125/108, 9/8, 10/9, 27/25, 16/15, 25/24, 81/80.

Knowing p , we find q = 1/(4 p ), and bring p and q to a common denominator. Then, by addition and subtraction, we find ten Pythagorean triples which stand in the first ten rows of the Babylonian table:

|

p |

q |

c |

b |

a |

|

6/5 = 144/120 |

5/24 = 25/120 |

169 |

119 |

120 |

|

32/27 =4096/3456 |

27/128 = 729/3456 |

4825 |

3367 |

3456 |

|

75/64 = 5625/4800 |

16/75 = 1024/4800 |

6649 |

4601 |

4800 |

|

125/108 = 15625/13500 |

27/125 = 2916/13500 |

18541 |

12709 |

13500 |

|

9/8 = 81/72 |

2/9 = 16/72 |

97 |

65 |

72 |

|

10/9 = 400/360 |

9/40 = 81/360 |

481 |

319 |

360 |

|

27/25 = 2916/2700 |

25/108 = 625/2700 |

3541 |

2291 |

2700 |

|

16/15 = 1024/960 |

15/64 = 225/960 |

1249 |

799 |

960 |

|

25/24 = 625/600 |

6/25 = 144/600 |

769 |

481 |

600 |

|

81/80 = 6561/6480 |

20/81=1600/6480 |

8161 |

4961 |

6480 |