Delimitation between Russia and Norway in the Arctic: new challenges and cooperation

Автор: Vyacheslav K. Zilanov

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Economics, political science, society and culture

Статья в выпуске: 29, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article analyzes the provisions of the Treaty between the Russian Federation and Kingdom of Norway on delimitation of the sea areas and cooperation in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean of 15 September 2010 and it also provides an assessment of the conformity of the Treaty to national interests of Russia. The article considers the results of its practical impact on fishing activity in the North-Western sector of the Arctic, especially in the Russian home fisheries. The author discussed steps necessary for the protection of national interests after the Treaty of 2010 and its influence on fishing in the North-Western sector of the Arctic. It is proposed to hold additional Russian–Norwegian negotiations to reach an understanding between parties about the home fisheries based on traditional character near the Spitsbergen Archipelago, as well as to adopt unified measures to control fishing and harmonize penalties for violation of the agreed fishing rules for all the fishing activities at the Barents Sea.

The Barents Sea, the Arctic Ocean, delimitation, collaboration, Russia, Norway, the Treaty on delimitation of marine living resources, continental shelf, 200-mile zone, fisheries policy, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, international treaties and agreements

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148318558

IDR: 148318558 | УДК: 327(47+481)(045) | DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2017.29.28

Текст научной статьи Delimitation between Russia and Norway in the Arctic: new challenges and cooperation

Signing and enactment chronology

The agreement between the Russian Federation and the Kingdom of Norway on the delineation of maritime areas and cooperation in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean (hereinafter — the “Treaty” or the “Treaty of 2010”) was signed in Murmansk on September 15, 2010 by the Minister of Foreign Affairs Russia S.V. Lavrov and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Norway J. Støre, in the presence of the President of the Russian Federation, D.A. Medvedev and Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Norway J. Stoltenberg.

It was assumed that the ratification of the Treaty 2010 would be carried out by the parliamentarians of the two countries before the end of 2010. However, this was impossible due to the opposition represented by the fishing community of the Murmansk, Arkhangelsk and other regions of Russia. They required additional time for consideration in accordance with the national interests of Russia. Parliamentary hearings on this issue were held, which did not lead to an unambiguous conclusion. Most speakers, specialists, scientists and practitioners cited arguments about the non-compliance of the Treaty with national interests and proposed rejecting its ratification.

Fig. 1 Signing of the Treaty, 15 September 2010. Photo: Lev Fedoseev. First published in “Murmansk Vestnik” 16 September 2010. No 169 (4812).

Nevertheless, the Treaty 2010 was first ratified by the Norwegian Storting (Parliament) on February 8, 2011 by 169 parliamentarians (100%) from 7 contracting parties. At the same time, parliamentarians stressed the relevance of the Treaty to the interests of Norway and noted the special contribution of the Norwegian participants in the negotiating process and the development of its provisions. Special congratulations from all parties represented in the Storting, including opposition ones, were received by Prime Minister J. Stoltenberg 1. At the same time, it was stressed that this is a historic achievement and a major Norwegian diplomatic victory.

In Russia, the 2010 Treaty was ratified by the State Duma of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation more than a month after the Norwegians, on March 25, 2011. Then it was approved by the Federation Council on March 30, 2011. At the same time, only 311 voted for its ratification deputies (or 69.1% of those involved in the issue) and all of them represented only one party — “Edinaya Rossiya”. This is a very low rate of voting, considering the importance of the document. Other parties — the CPRF, the Liberal Democratic Party, and “Spravedlivaya Russia” — criticized the provisions of the Treaty and even offered to reject it. Despite this, the Treaty was ratified using the “voting machine”, and this was accompanied by a special “Statement regarding the delineation of maritime spaces between the Russian Federation and Norway in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean” (See Annex 1). The President of the Russian Federation D.A. Medvedev signed federal law on ratification of the Treaty on April 5, 2011 (No57-FZ).

The exchange of ratification instruments between the representatives of Russia and Norway was only carried out on June 7, 2011. On the 30th day after this procedure, the Treaty entered into force, in accordance with its Art. 8. However, certain fishery agreements that were achieved earlier, e.g., the Protocol on Provisional Rules for Fishing in an adjacent section of the Barents Sea of January 11, 1978, continued to apply “In the former disputed area ... during of the transitional period for a period of two years from the date of entry into force of this Treaty” (Art. 2, Annex I to the Treaty 2010). Thus, considering the transition period, the Treaty had entered into the full force on July 7, 2013, and four years it has been implemented by Russia and Norway. It gives a certain, but so far little material for assessing those goals and expectations that were stated in the Treaty itself.

Basic provisions of the Treaty

The text of the Treaty 2010 contains a preamble of 11 paragraphs, 8 articles, Annex I “Fisheries” and Annex II “Cross-border hydrocarbon deposits”. Here is a brief analysis (article by article) of the basic provisions of the Treaty with a regard to their application in resource activities.

In the preamble the main purpose of the Treaty is proclaimed as “the maintenance and strengthening of good-neighbor relations, stability and strengthening cooperation in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean”2 and “to complete the demarcation of maritime spaces of the Parties”.

As implementation of the above-mentioned targets, the importance for both sides of the "values of living resources for coastal fishing communities", "the traditional nature of Russian and Norwegian fisheries in the Barents Sea" and the responsibility "with respect to the conservation and rational management of the living resources of the Barents Sea and in the Arctic Ocean. "

No less importance is attached to hydrocarbon resources, which is reflected in the text of the preamble as "the importance of efficient and responsible management of their hydrocarbon resources." It is these two areas of economic activity in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean — fisheries and the use of hydrocarbon resources — that are devoted to Annex I "Fisheries issues" and Annex II "Transboundary hydrocarbon deposits".

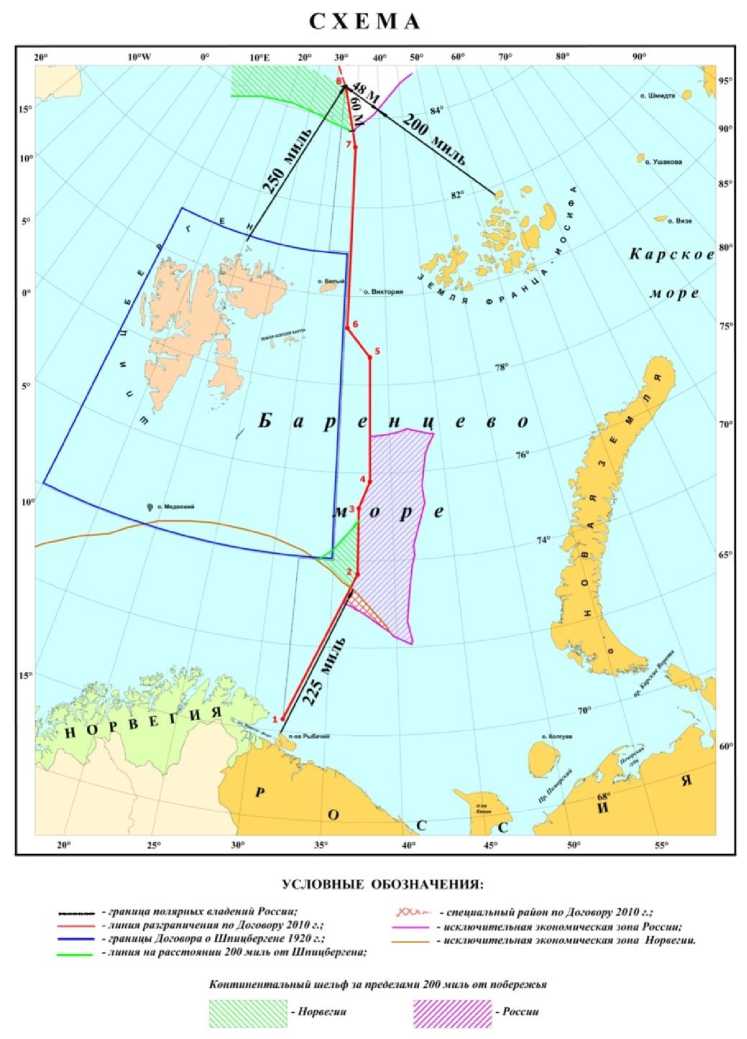

Article 1 secured the agreements reached by the Parties on the delineation of maritime areas in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean as 8 points in appropriate coordinates, connected between each other from the South to the North. The line of demarcation is reflected not only in coordinates, but also on the map-scheme attached to the Treaty (Fig. 2). The length of the line is about 844 miles or 1,689 km.

Unfortunately, this Article, as well as the others and the preamble of the Treaty, have no explanation of the term “maritime areas”. What is their meaning for the Parties? The continental shelf? Exclusive 200-mile economic zones? The fishing zone around Svalbard? Territorial sea? Or all of them are understood under the term “maritime areas?” By the way, the term “maritime areas” is not registered in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea of December 10, 1982, referred to by the Parties in the preamble of the Treaty, as one of the basics for making decisions on delimitation. In Russian home treaty practice, the term “maritime areas" was first used in the Agreement between the Government of the USSR and the USA on the maritime space delimitation line of June 1, 1990, which was ratified by the US Senate on September 16, 1991, but was not ratified by the USSR and it is still not ratified by Russia.

The question of the content of the term “maritime areas” used in the Treaty 2010 is not only of a theoretical nature, but primarily of practical importance, both for fishing and exploration and development of hydrocarbons. Attempts, made by the Union of Fishermen of the North (hereinafter — SRPS) to receive clarification from the Russian Foreign Ministry involved in the development of the provisions of the Treaty from our side and led the Russian delegation in negotiations with the Norwegians, are still unsuccessful.

Article 2 defines the obligations of the Parties to comply with the line of delineation and states that they “should not claim, and not exercise, any sovereign rights or jurisdiction of the coastal state in maritime areas outside this line”. It means that everything that is located East of the line of delineation belongs to the competence of Russia, and everything that is West of the line of delimitation is the competence of Norway.

Article 3 describes the arrangements of the Parties for the “special area”, which has the form of “kerchiefs”/ It is a small area, allegedly handed over by the Norwegian side to the Russian side. At the same time, Norway has never owned, either legally or practically, this small and economically unimportant sea area. The question arises: “How is it possible to convey something that you’ve never owned?”. On the other hand, after a “deal”, Russia automatically expanded its 200-mile exclusive economic zone beyond this limit — up to 225 miles, which contradicts the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea of 1982. In addition, § 2 Art.3 let Russia the adoption of the relevant laws, regulations on its sovereign rights or jurisdiction in the “special area”, as well as its application on maps. It has not yet been fully implemented by us. In general, the provision of Art. 3 does not have a reasonable explanation for its adoption by the Russia.

Article 4 defines the provisions for close cooperation, and the Annex I specifies the principles and tools for its implementation in fisheries “to maintain existing shares in the total allowable catch”, and states that “the conclusion the Treaty shall not adversely affect the capabilities of each Party in fisheries”. These provisions are important for both Russian and Norwegian fisheries. Taking into account the provisions reflected in Annex I, and, first of all, the prolongation of the Agreement on Cooperation in Fishing from April 11, 1975 and the Agreement on Mutual Relations in the Field of Fisheries of October 15, 1976 for a 15-year period , as well as the continuation of the work of the Joint Russian-Norwegian Fisheries Commission (hereinafter — JRNC) for adoption of the total allowable catches, the definition of reciprocal quotas and measures for regulating fisheries, is, on the one hand, a good basis for the continued sustainable fisheries of both parties to all the water area of the Barents Sea. At the same time, the absence in this Article, as in the entire Treaty 2010, of references to the maritime region falling under the Svalbard Treaty 1920, which is the most important in the Russian fishing, and the provisions of Article 2, creates in the long term real threat to the continuation of sustainable Russian fishing in the offshore area of the Spitsbergen archipelago.

Article 5 describes arrangements and procedures for the exploitation of hydrocarbon resources on the continental shelf, where they lie on both sides of the demarcation line. Annex II provides a detailed procedure for the joint development of those transboundary oil and gas fields. At the same time, it allowed inspecting the hydrocarbon extracting machinery located on continental shelf, which operates transboundary deposits. To consult and resolve emerging issues, related to the use of transboundary hydrocarbon resources, the Parties shall establish a Joint Commission.

Article 6 emphasizes that the Treaty should not prejudice the rights and obligations of the Parties under other international treaties to which both Russia and Norway are parties, and which are effective at the time of signing and entry into force of this Treaty. It can be assumed that under the “other international treaty”, the Parties imply the Svalbard Treaty of 1920 and that the Art. 6, in the opinion of the developers of the 2010 Treaty [1, Kolodkin R.A., p. 27; 2, Titushkin V.Yu., p. 382], allows Russia, “to justify its position on the so-called fish-protection zone around Spitsbergen”, but not recognize it. At the same time, as A.K. Krivorotov rightly observed [3, Krivo-rotov A.K., p. 70], the same provisions could equally be used by Norwegians for their interpretation of the regime of the maritime areas around Svalbard, justifying the Norwegian 200-mile fishprotection zone, introduced here. Sharing such a conclusion Krivorotov A.K., I would pay attention to the following: even if we assume that the argument Kolodkin R.A. that this Article protects our resource interests in the maritime area of Spitsbergen is correct, then how does this relate to the provisions of the Article 2 of the Treaty? And it explicitly states that everything that is west of the line of delineation does not belong to the sovereign rights or jurisdiction of the coastal state, that is, to Russia. Then to whom does this apply? The answer is obvious — to Norway. Thus, Article 6 is of a general nature and cannot be used, considering other provisions of the Treaty 2010, as a legal instrument for the protection of Russian interests in the maritime region of Spitsbergen.

Signs as follows:

Black line means Russian Polar territories; Red line is the demarcation line according to the Treaty 2010; Blue line is borders of the Spitsbergen Treaty 1920; Green Line is the 200 miles line from Spitsbergen; Orange crosses is the special area according to the Treaty 2010; Violet line is the Russian Exclusive economic zone; Brown line is the Norwegian Exclusive economic zone. Continental shelf outside the 200-miles zone: Norway (green field), Russia (violet field). All distances measured in miles.

Fig. 2. Maritime space demarcation line according to the Treaty between Russia and Norway, 15 September 2010

-

3 Kislovskiy V.P. S pozicii mezhdunarodnogo prava — nichtozhen! [From the international legislation perspective — is insignificant], Morskie vesti Rossii, 2015. No. 12. pp. 13–15.

Article 7 contains important provisions stating that the Annexes to the Treaty are an integral part of it. However, it also provides the possibility of amending the Annexes through separate agreements, which come into force in a certain order and from the date secured in these agreements.

Article 8 specifies the mandatory procedure for ratification, the date of entry into force of the Treaty and the fact that the texts of the Treaty are made in Russian and Norwegian languages, both texts being equally authentic.

At the same time, it is noteworthy that the texts in Russian and Norwegian do not coincide in meaning in some cases. This might be the origin of conflicts when it comes to the application of the Treaty. In the opinion of A. Krivorotov. [3, p. 77], who also speaks Norwegian, “the heavyweight style ... in Russian and in Norwegian texts of the Treaty, clearly outlined in English, indirectly testifies to the haste in its preparation, which did not even allow the translation to be completed”. Even more negative assessment of the inconsistency in fishing issues in Russian and Norwegian texts is given by Ph.D. Lukasheva E.A. [4, Lukasheva E.A., pp. 33–35], who revealed several significant differences in the texts. The most important of them are given in the table 1 compiled earlier based on the E.A. Lukasheva’s analysis.

Table 1

Comparative analysis of the Russian and Norwegian texts of the Delimitation Treaty, 15 September 2010, regarding fishery

|

Russian text |

Translation of the relevant provisions from the Norwegian text. The translation s made by a specialist in fisheries with knowledge of Norwegian language and the relevant terminology (PhD. Lukasheva E.A.) |

|

Sixth indention of the preamble: |

|

|

“...coastal fishery communities...” |

“... coastal fishing communities...” |

|

“... usually had fisheries in these areas” |

“... usually has fisheries in these areas” |

|

Eights indention of the preamble: |

|

|

“... and responsibility as the coastal states...” |

“...and primary responsibility as the coastal states...” |

|

Article 4 § 1: |

|

|

“...should not have negative effect on opportunities ...” |

“...should not damage the relevant opportunities ...” |

|

Article 4 § 2: |

|

|

“Aiming this, the Parties continue to cooperate closely in the field of fisheries to retain their existing share in the total allowable catch and to ensure relative stability of fishing activities for each respective type of fish stocks” |

“To this end, the two Sides will continue close cooperation on fisheries to retain their respective shares of the total allowable catch and to ensure relative stability of fishing in respect of certain of the stocks concerned ” |

|

Annex I Fishery issues. Art 2. |

|

|

"...technical regulations concerning of cell size of nets and minimum catch size established by each of the parties for their fishing vessels are used ...” |

“... technical requirements, the cell size of networks and the minimum fish size set of each of the parties for their fishing vessels operate …” |

All these inconsistencies of the texts in Russian and Norwegian languages need to be ad- dressed, especially because the Norwegian text regarding the fisheries, fully meets the semantic approach on these issues, the Russian practitioners of the Northern basin.

What did the Treaty delimit?

As it was mentioned in the Treaty itself, certain "sea spaces" were subjected to the delimitation between Russia and Norway in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean. There are no definitions of this term in the Treaty. There are no explanations on this issue from the relevant competent Russian authorities.

However, the last indention of § 1, Art. 1: “The final line of the boundary-line ... connecting the easternmost point of the outer limit of Norway's continental shelf and the western point of the outer border of the continental shelf of the Russian Federation (highlighted by the author)”, which indicates that all the way from point 1 to point 8 (almost 1, 7 thousand km) — (see Fig. 2), the sides divided, first of all, the continental shelf of the Barents Sea and partially the shelf in the North-Western sector of the Arctic. As for the delineation of the 200-mile exclusive economic zones (hereinafter — the EEZ), which are recognized by both Parties (I recall that the 200-mile fish protection zone around Svalbard is not such), then in the text of the Treaty and on the enclosed map, there are no mention of this. Meanwhile, this issue is of a great practical importance in the implementation and control of fishing in areas of the direct line of delineation between the Parties to their recognized EEZs. In this regard, below there is a map-scheme, which was compiled by the author of this article and cartographer V.P. Kislovskiy with the involvement of experts from the Northern Basin and the NPO “Marine Informatics”, and which is temporarily used in the analysis of home and foreign fisheries in the Barents Sea and in the Northwest Sector of the Arctic (Fig. 3).

As follows from the data presented in Fig. 2 and 3 map schemes of the southern part of the region adjacent to the continental coast of Russia and Norway, the line of delimitation concerns both the shelf and the EEZ. Further beyond 200 miles from the coasts and to point 5, this line of delineation applies only to the continental shelf. Then again between 5-6-7-8 points are delineated both the shelf and, it can be assumed, the EEZ, but no further than 200 miles from their coasts where the zones do not overlap.

In the central part of the Barents Sea there is an open part of it — an enclave called Loop Hole, bounded from the south, east and north by the outer boundary of the EEZ of Russia, and from the west by a contractual line of demarcation. However, the continental shelf in this open area of the Barents Sea is Russia's shelf with all the ensuing consequences.

With this interpretation of the purpose of the line of delineation of maritime areas, several issues arise, among which the most important and fundamental is: “Did Russia, by signing and ratifying the 2010 Treaty on the delimitation of maritime spaces, recognized the existence of the shelf around Spitsbergen and its belonging to Norway, and recognized the 200-mile fish-protectionzone around Svalbard?” I believe that this really follows from the analysis of the line of demarcation and proceeds from the provisions of the Treaty It should be added in fairness that such a conclusion is based on an analysis of all the provisions of the Treaty, including delineation, cooperation in fisheries and the use of hydrocarbon resources in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean. Does this ap- proach meet the national long-term interests of Russia? I think that it does not.

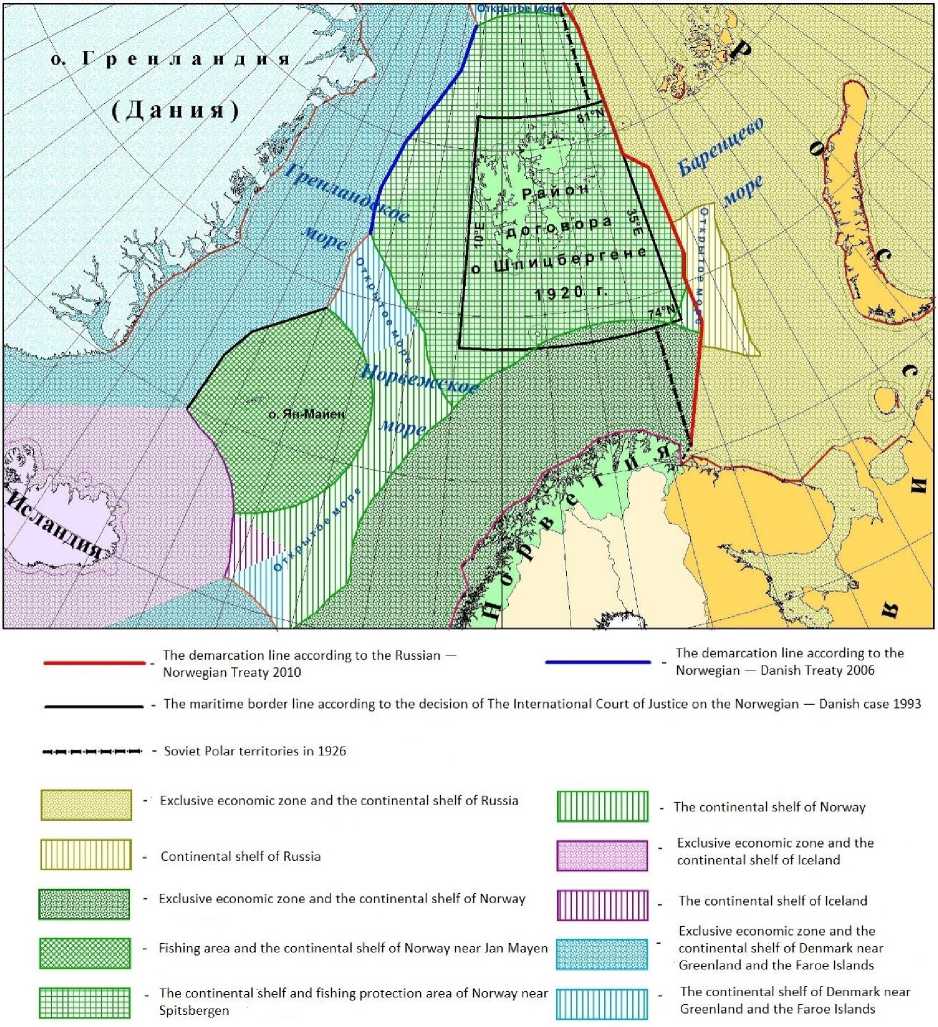

Fig 3. The spatial position of the various zones, areas of jurisdiction in the Barents, Norwegian and Greenland Seas and the line of demarcation under the Treaty of 2010.

Spitsbergen fight

An analysis of the provisions of the 2010 Treaty and its Annexes is detailed in many articles by scientists, international law experts, international relations, historians, politicians, practitioners. Several works can be mentioned [5, Melkov G.M.; 1, Kolodkin R.A.; 2, Titushkin V.Yu., 3, 6, Krivo- rotov A.K.; 7, 8 Lukin Yu.F.; 9, 10, Vylegzhanin A.N.; 11, 12, Oreshenkov A.M.; 13, Kislovskiy V.P.; 14, Bekyashev K.A.; 15, Plotnikov A.Yu.; 16, Portcel A.K.; 17, Didikh V.V.; 18, 19, 20, Zilanov V.K.] Khlestov O.N., as well as the author of this article evaluated the treaty in its interviews 4,5. We should also note the journalistic materials of Kalashnikov L.I. 6, Oreshenkov A.M. 7 and Kislovskiy V.P. 8 A number of these works reflect the point of view of official representatives of Russia — the developers of the text of the Treaty (Kolodkin R.A., Titushkin V.Yu.), as well as those few scientists, specialists in the field of international law (Khlestov O.N., Bekyashev K.A.), who, as a rule, are in solidarity with the position of the developers and defend the compliance of its provisions with the national interests of Russia. At the same time, most of the other articles, mentioned above, reflect the opposite assessment of the Treaty — the inconsistency of its provisions with the national interests of Russia due to unjustified concessions on our shelf, the lack of a factor in the extent of the shoreline, the provisions of the Treaty on Spitsbergen 1920, the boundaries of the polar possessions of the USSR in 1926 and departure from the principle of justice (Melkov G.M., Kalashnikov L.I., Krivorotov A.K., Plotnikov A.Yu., Kislovskiy VP 9, etc.). The most complete analysis of different points of view regarding the provisions of the 2010 Treaty and its impact on Russian resource activities was carried out by Dr. Yury F. Lukin [7, pp. 14–17]. In his study, Lukin Yu.F., using SWOT analysis, identified both the strengths and weaknesses of the Treaty.

Among the strengths he noted: the completion of the delimitation process, the establishment of the outer limits of the continental shelf, the opening of hydrocarbon resources in the previously disputed area, the continuation and development of cooperation in fisheries and other areas, and the creation of prerequisites for the promotion of the Russian application for the continental shelf in the Arctic Ocean.

Among the weaknesses of the 2010 Treaty Lukin Yu.F. discussed that the Treaty does not resolve the existing differences of the parties in the maritime region of Spitsbergen. The Treaty of 2010 also destroys the border of the polar possessions of the USSR in 1926, “pushing” it to the east for 60–70 miles because of differentiation. According to Yu.F. Lukin, the Treaty “contradicts, openly violates the Treaty on Spitsbergen 1920”.

In another study on this issue, Honored Lawyer of the Russian Federation, Doctor of Law, Professor G.M. Melkov [5, pp. 10–13], who presented at the parliamentary hearings in the State Duma a detailed Legal Opinion to the 2010 Treaty, concludes that the wording of his provisions and article 2, lead to Russia's recognition of "Norway's continental shelf and 200-mile zone around Spitsbergen" All this is already reflected, above all, on the activities of domestic fisheries in the marine area of Spitsbergen, where annually we harvest 160–230 thousand tons.

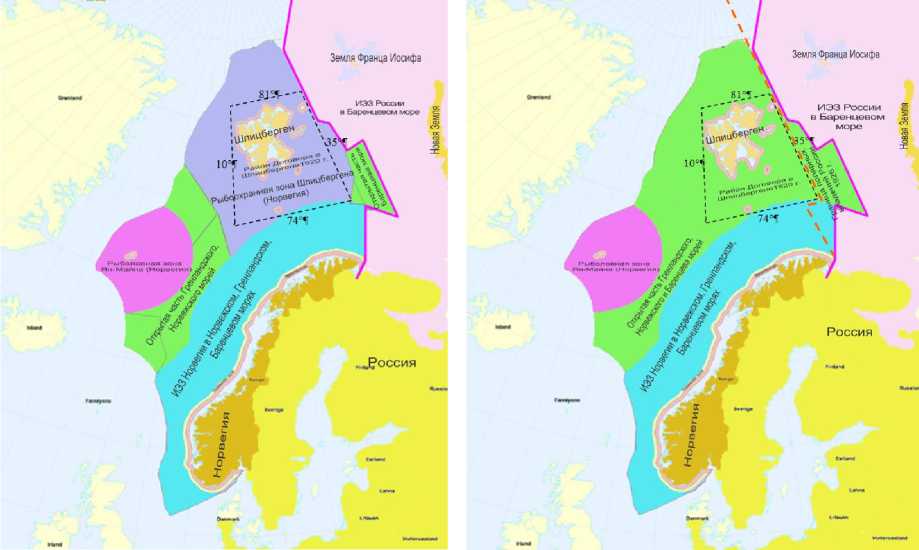

With the entry into force of the 2010 Treaty, fishing vessels under the flag of the Russian Federation continue to fish for marine living resources in the maritime region of Spitsbergen at the expense of their national quota adopted within the framework of the RNCF. At the same time, the capitals of Russian vessels carrying out fishing operations here are guided by a special Explanation of the Federal Fishery Agency of June 27, 2011 (hereinafter referred to as "Explanations"), according to which the sea area around Spitsbergen is considered by Russia as an open sea area. The viewpoint of Norway is different: around Spitsbergen there was and, despite the 2010 Treaty, a 200-mile Norwegian fishing zone with all the ensuing consequences for the Russian fishing fleet (Fig. 4).

At the same time, the captains of Russian fishing vessels, in accordance with the “Explanations” of Rosrybolovstvo, continue, as before the entry into force of the Treaty, to allow Norwegian Coast Guard inspectors (KYSTVAKT or known to fishermen as BOHR) on board the Armed Forces Norway, to verify the implementation of fisheries management measures in the maritime region of Spitsbergen. As a result, protocols are usually drawn up; captains of Russian fishing vessels, in accordance with the “Explanations”, did not sign these protocols and informed their shipowner about the situation. In the opinion of Norwegian inspectors, there are suspicions or violations of fishing rules (issued by the Norwegian authorities), the vessel is delayed, and the proceeding is carried out. If it is impossible to identify all the circumstances of the violations, the vessel is escorted to the Norwegian port and to the Norwegian courts in accordance with the Norwegian laws. Such arrests — arrests of Russian fishing vessels in the maritime region of Spitsbergen — occur regularly. In recent years, it was 1–3 vessels per year. As for the inspections of Russian fishing vessels by Norwegian inspectors of BOHR in the maritime region of Spitsbergen, they cover almost 100% of vessels. As a rule, most vessels are inspected 2–3 times during the period of their pres- ence in the fishery. After each such inspection, the ship's master receives a written warning about the consequences of the failure of the Norwegian authorities to receive daily information on whereabouts, catch, etc. when working in the Norwegian Spitsbergen 200-mile Norwegian fish protection zone and the requirement to sign this warning. The latter is dismissed with a reference to “Explanations”, and information about this is sent to the shipowner.

Позиция Норвегии относительно статуса морских пространств, касающихся рыболовства морских живых ресурсов в Баренцевом, Гренландском, Норвежском морях.

Позиция России относительно статуса морских пространств, касающихся рыболовства морских живых ресурсов в Баренцевом, Гренландском, Норвежском морях.

In the left:Norway's position on the status of marine spaces relating to fisheries and marine living resources in the Barents, Greenland and Norwegian seas. There is a fish protection area near Spitsbergen.

In the right: Russia's position on the status of marine spaces relating to fisheries and marine living resources in the Barents, Greenland and Norwegian seas. There area near Spitsbergen is supposed to be regulated by the Treaty of 1920

Fig. 4. Doctrinal approaches of Russia and Norway regarding the status of the marine area around Svalbard.

All proposals of the Russian side to resolve these acute conflict situations, helped to work out coordinated joint control and inspection procedures for fisheries management measures, but they are rejected by Norwegians as affecting their jurisdiction in this area. After the 2010 Treaty, the Norwegian side had additional arguments in its favor on this issue: first, under the Treaty (Article 2), Russia recognized Norway's jurisdiction and sovereign rights to the west of the boundary line, which also includes the 200-mile fish protection zone of Spitsbergen. It is this issue — the recognition of Norway's rights to the marine region of Spitsbergen and the provision of optimal conditions for the work of the Russian fleet in it in the conditions of entry into force of the Treaty 2010 — it was one of the main decisions of the deputies and senators of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation about its ratification. Without convincing arguments on this issue during the open Plenary session of the State Duma from the official representative of the President of the Russian Federation, Deputy Foreign Minister Titov V.G., the deputies nevertheless decided to ratify the Treaty (with the votes of only one fraction), accompanied by the statement “In connection with the delineation of maritime spaces between the Russian Federation and Norway in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean” (Annex 1). The legislators stated the main provisions of the Treaty and expressed hope for the possible further strengthening of bilateral cooperation after its entry into force, emphasized the importance of not incurring, “any damage to the rights and obligations of the Parties under other international treaties” and “of course, the Treaty of Spitsbergen of 1920”10. This is the only one of all official documents related to the 2010 Treaty, mention of the importance for the Russian resource activities of the sea area, subject to the Spitsbergen Treaty of 1920, Russian parliamentarians send an important signal to the Norwegian side about the need to take this into account and consider with co-operation in the area. Unfortunately, the text of the Declaration itself, in my opinion, is too weak regarding defending Russian interests in the maritime region of Spitsbergen, and its level (it is not part of the Federal Law on Ratification of the Treaty) is very low. It was not even officially handed over to the Norwegian side in the exchange of instruments of ratification, although it was published in the Parliamentary Gazette.

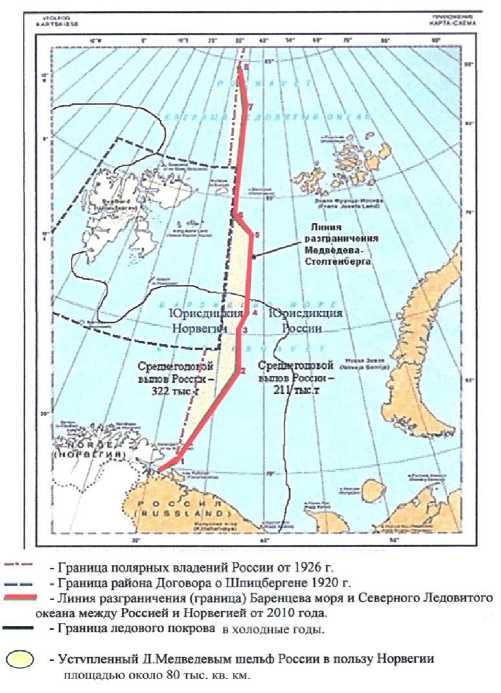

As mentioned above, the main concerns — the challenges regarding the 2010 Treaty — are due to the uncertainty of the possibility of a long-term continuation of the work of the domestic fleet to the west of the line of delineation, where our fleet, on average, up to 322 thousand tons a year, 160–230 thousand tons in the offshore area of Spitsbergen. The importance of this area for domestic fishing in the Barents Sea especially increases in the cold oceanographic years, when almost the entire eastern part of the sea, and this EEZ of Russia, is covered with ice, and it is impossible to fish here. And the main objects of fishing — cod and haddock — migrate to the western, warmer regions of the sea.

The location of the line of demarcation under the Treaty of 2010 and the absence in the text of its guaranteed formulations for ensuring the continuation of the work of the domestic fishing fleet in the maritime region of the Spitsbergen archipelago essentially create a serious threat in the future, under certain circumstances (sanctions, etc.), the Norwegian side closes domestic fishing in the eastern "ice mesh" of the Barents Sea (Figure 5). This, long before the signing of the Treaty, drew the attention of its developers, representatives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, fishermen of the Northern Basin and Rosrybolovstva. Moreover, on March 11, 2010, six months before the signing of the Treaty, in the name of the President of the Russian Federation Medvedev D.A. a letter was sent with concrete proposals for amending the draft Annex I to the Treaty (Annex 2). In the future, these amendments were reviewed and approved during the meeting of the ad hoc Working Group (I was a member of the working group on fishery) under the chairmanship of the head of Rosrybolovstva Krainy A.A. and sent on May 17, 2010, 4 months before the signing, to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia, so that they are considered in the final agreement with the Norwegian side of the draft text of the Treaty. Unfortunately, not all the proposals of the Rosrybolovstvo Working Group were considered in the text of the 2010 Agreement [14, p. 14]. This is especially true of guarantees to ensure the interests of domestic fishing in the maritime region of Spitsbergen: they were rejected by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs without explaining the reasons. I believe that such an approach suggests that the overriding motives of its hasty development and the signing was not the solution of the whole complex of problems, including fishing issues, and settlement of roofing, to the problems associated with the exploration and development of hydrocarbon resources in the continental shelf The Barents Sea. The latter is more in the interests of Norway than Russia.

Brown line is the border of the Russian Polar areas in 1926; Black line is the border according to the Spitsbergen treaty 1920; Red line is the border line in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean between Russian and Norway in 2010; Curved black line is ice cover border in the cold years; Yellow field is the shelf of Russia given to Norway by D. Medvedev, the area equals to approx. 80 000 km2

Fig. 5. Areas of jurisdiction of Russia and Norway after the entry into force of the Treaty 2010, the average annual catch of Russia in the eastern and western regions of the Barents Sea, the spread of the ice cover in the cold years and the areas of the continental shelf ceded to the Norwegians.

With the entry into force of the 2010 Treaty, both parties in relation to fishing in the maritime area of Spitsbergen retain a delicate balance of equilibrium, which at any time may result in a Russian-Norwegian conflict. And in this possible conflict legal instruments, based on the provisions of the 2010 Treaty, on the Norwegian side. Special attention is paid to this by the Doctor of Law, Professor G.M. Melkov. [5, pp. 10–13; 21, pp. 231–245]. In his legal opinion, he believes that since the entry into force of the 2010 Treaty:

"- Russia will no longer have grounds to object to the 200-mile zone of Norway around Spitsbergen (and until the Treaty of 2010 such grounds were in accordance with the Treaty of Spitsbergen of 1920).

-

- Russia will no longer have grounds to object to Norway's continental shelf around Spitsbergen (and until the Treaty of 2010 such grounds were in accordance with the Treaty of Spitsbergen of 1920).

-

- Russia will no longer have reason to object to Norway's territorial sea around Svalbard (and until the Treaty of 2010 such grounds were in accordance with the Treaty of Spitsbergen of 1920).

-

- Any economic activity of Russia after the entry into force of the Treaty of 2010 in the marine areas around Svalbard based on the Svalbard Treaty becomes legally impossible. Such an activity is possible only if it is fully subordinated to Norway's legislation in its territorial sea, 200-mile zone, continental shelf. "

Sharing such conclusions of Professor G.M. Melkov, I note that they were brought to the attention of Russian negotiators — representatives of the Foreign Ministry. Why the latter neglected them is the subject of future special studies. Here I just want to draw attention to the fact that the mechanisms of decision-making at the federal level in such situations need to be adjusted.

As for the delimitation of the continental shelf in the Barents Sea, here, too, Russia incurred losses in comparison with the previously claimed claims, which were sufficiently substantiated. According to various estimates, Russia lost to Norway from 80 to 143 thousand square meters. km of the continental shelf in the Barents Sea [Fig. 5; 19; Kislovskiy V.P.11]. Trying to refute such losses during the parliamentary hearings and at the plenary session in the State Duma, the representative of the President of the Russian Federation, the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Titov V.G. [22, Transcript of the Parliamentary Hearings, p. 337] even quoted this passage: “If we take the Barents Sea, then about 860,000 sq. km”, and “Norway remains about 510 thousand” However, I note that the object of delineation between the Stones was not the Barents Sea, but the continental shelf and the EEZ. And these are completely different things. It is because of concessions on the part of the continental shelf and created threats, based on the provisions of the 2010 Treaty, on a possible Norwegian ban on fishing for our fishermen to the west of the line of delimitation, especially in the maritime region of the Spitsbergen archipelago, the deputies of the three factions of the State Duma, fishermen of the Northern Bassein and opposed its ratification. Moreover, the Treaty of 2010 for the first time created in the Russian-Norwegian fishing relationship the legal basis for such a unilateral decision by the Norwegian side.

This follows from the research of Kislovskiy V.P.12, who, analyzing the Treaty for compliance with its several provisions of international law and paying attention to the absence in the text of even mentioning the Treaty of Spitsbergen of 1920, which, in determining the line of delimitation of the continental shelf in the Barents Sea, is unquestionably of particular importance, comes to the conclusion that the 2010 Treaty “not only did not solve the existing problems, but also created new ones, provoking a lot of questions”.

A detailed analysis of the special significance for resource activities in the area covered by the Svalbard Treaty of 1920 and the rationale for Russia's position on the non-recognition of Norway's 200-mile fish protection zone as declared by Norway is given in the works of Dr.Sc., Professor Vylegzhanin A.N. [23; 10].

Is it possible for the parties to the Treaty of 2010 to come to an optimal solution to the emerging problems, primarily in fishing in the maritime region of Spitsbergen, using the principle of "cooperation" proclaimed in it? As the four-year practice of its application shows, so long as the status quo is preserved. Consequently, opportunities remain to achieve a mutually acceptable solution to this most complex problem.

The 2010 agreement entered into force, and its provisions, regardless of its positive and negative assessments, have been applied in practice by both Russia and Norway. As the Doctor of Jurisprudence, professor Vylegzhanin A.N. [10, p. 5], "in the present time the Treaty is a legal reality, part of the current international law, which provides for very specific rights and obligations of Russia and Norway. Both sides are to fulfill this Treaty" At the same time, this does not exclude the possibility of introducing amendments and amendments to the Treaty and its Appendices, which, naturally, can only be adopted with the consent of the Parties.

Proceeding from the above and considering the relevant provisions of the 2010 Agreement concerning the possibility of amending, above all in the Annex, it would be timely to implement previously made and adjusted by considering the practice of applying the Treaty in recent years and this study, the following changes:

-

1. Conduct Russian-Norwegian negotiations on amending Annex I of the 2010 Agreement relating to fisheries issues by providing relevant proposals to the Norwegian side, in advance, developed by scientists, practitioners and approved by Rosrybolovstvo on this issue.

-

2. Inform Norway that, prior to the adoption of amendments to Annex I, Russian vessels will continue to fish in the offshore area of the Svalbard archipelago in compliance with the regulatory measures and fishing rules adopted by the RNC. Control over the activities of vessels flying the flag of Russia is carried out in this area only by the Russian competent authorities.

-

3. The implementation of special Russian-Norwegian negotiations for developing and adopting common regulatory measures and fishing rules, harmonized procedures for verifying their execution by both Russian and Norwegian vessels is promising. And, penalties in case of their violation in all fishing areas of the Barents Sea irrespective of areas of jurisdiction.

-

4. To send to the Norwegian side the Statement of the State Duma adopted by it upon ratification, the unchanged position of Russia on the strict observance of the Svalbard Treaty (1920) and the non-recognition of the so-called Norwegian 200-mile fish protection zone, as before, introduced around the Spitsbergen archipelago.

-

5. To reconsider the decision to expand the Russian exclusive economic zone beyond 200 miles due to the allegedly received from Norway “Special Area” in connection with violations of the relevant provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 1982

-

6. Develop and adopt at the national and international levels special environmental requirements for the exploration and development of hydrocarbon resources on the shelf of the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean. It is necessary to give preference to the preservation of traditional fisheries, the environment, species diversity and the gene pool of marine living resources.

-

7. To initiate the establishment of a Russian-Norwegian Center for Monitoring the State of Marine Living Resources and Controlling the Activity of Fishing Vessels in the Barents Sea and the International Arbitration Court on disputes related to economic activities in the offshore area around the Spitsbergen Archipelago.

Based on the experience of the negotiation process in the development and adoption of decisions by the Russian competent authorities under the 2010 Treaty, it is necessary to conduct internal events, including:

-

1. Repeated analysis of previously taken, as it turned out, erroneous decisions regarding the negotiations on the Treaty of 2010 and the procedure for making such decisions, as well as the formation of the composition of the delegation. Based on the analysis, it is necessary to improve the decision-making procedure by the relevant competent Russian authorities. In the future, it is necessary to envisage the participation of specialists, scientists, professional public nongovernmental organizations, representatives of the business community and regional executive and legislative bodies on issues of major national importance and relating to them.

-

2. Development and adoption of a federal target program for the construction of an up-to-date Arctic scientific research fleet for monitoring the state of living marine resources and identifying an additional resource base for domestic fisheries in the Northwest Arctic and adjacent seas.

-

3. The imposition of control over the proper implementation of the 2010 Treaty by the relevant SRIs of the Northern Basin in close cooperation with economic entities operating in the maritime region that is subject to its operation.

Russia's proper conduct of the above-mentioned measures at the international and domestic levels will indeed create conditions for the further development of Russian-Norwegian cooperation in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean.