D.G. Messerschmidt’s collection of Siberian antiquities in drawings at the St. Petersburg Archive of the Academy of Sciences

Автор: Tunkina I.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.51, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This study focuses on the drawings of items collected during D.G. Messerschmidt's fi rst multidisciplinary expedition to Siberia in 1719–1727. Pictures of the artifacts have been preserved among the documents held by the Academy of Sciences Archive in the personal papers of the traveler, which includes his fi eld journals, the appendices of his reports to the Pharmaceutical (Medical) Registry, and a large handwritten treatise “Sibiria Perlustrata” (1727), outlining the expedition's fi ndings. In 1728, Messerschmidt's archaeological collection was included as part of Peter the Great's Siberian Collection, exhibited at the Kunstkamera. Watercolor and pencil drawings and engravings depicting the exhibits are identifi ed. Handwritten descriptions and drawings of the items have made it possible to a certain extent to reconstruct the fi rst encyclopedist's Siberian archaeological collection, which perished during the 1747 fi re at the Kunstkamera. As Messerschmidt's graphic works demonstrate, he documented items spanning the time from the Bronze Age to the Late Middle Ages and covering the territory from the Urals to the Trans-Baikal region, including things imported from Western Europe, China, and Central Asia. Also, he collected archaeological items representing virtually all cultures of the Minusinsk Basin. It is concluded that in the fi rst third of the 18th century, Messerschmidt's collection was the world's largest and most representative assemblage of artifacts from northeastern Eurasia.

Academy of Sciences Archive, D.G. Messerschmidt, personal papers, Kunstkamera, Peter the Great’s Siberian Collection, drawings of archaeological artifacts

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146822

IDR: 145146822 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2023.51.1.100-107

Текст научной статьи D.G. Messerschmidt’s collection of Siberian antiquities in drawings at the St. Petersburg Archive of the Academy of Sciences

One of the most valuable collections in the first scientific archive of Russia (currently the St. Petersburg Branch of the Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences) is that of Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt (1685–1735)— Doctor of Medicine, scholar and encyclopedist, who first explored the northeast of Eurasia (Novlyanskaya, 1970; Perviy issledovatel…, 2019; K 300-letiyu…, 2021; Lehfeldt, 2023). Messerschmidt, a Pomeranian German from Danzig, was invited to serve in Russia and was assigned to the Pharmaceutical (since 1721, Medical) Registry. On November 15, 1718, upon the decree of

Peter the Great, he was sent to Siberia, “to search for all sorts of rarities and pharmaceutical items, herbs, flowers, roots, and seeds, and other articles belonging to medicinal compositions…” (Perviy issledovatel…, 2019: 201). During the eight-year expedition (1719– 1727), D.G. Messerschmidt expanded this research program and, on his own initiative, made surveys and studies in the ancient history and archaeology of Siberia, examined collections of archaeological objects (and their drawings) collected by private individuals, including the first Siberian Governor M.P. Gagarin and his successor the Governor-General A.M. Cherkassky, governors and commandants of forts, merchants, exiled Swedes and

Germans (“Carolins”), grave robbers, etc. (Tunkina, Savinov, 2017; Savinov, Tunkina, 2022).

Visualization of archaeological objects discovered and recorded during Messerschmidt’s expedition played a crucial role in his research (Bondar, Zorin, Tunkina, 2019; Tunkina, 2021). In his travel journal, on May 28, 1722, Messerschmidt wrote bitterly that he was unable to engage his companions in scholarly works, which consisted mostly in making records and drawings (SPbF ARAN. F. 98, Inv. 1, D. 1, fol. 144v). Therefore, he had to take the drawing duties on himself. Starting in July 1722, sporadic drawings, including those of archaeological artifacts, appeared in the expedition journals. The daily records include pages with empty spaces left where drawings, ground plans, and sketches of maps were intended to be included in the future.

At the beginning of 1720, Messerschmidt did not yet realize the necessity for making mandatory copies not only of official correspondence with the authorities, but also of all maps and drawings which were sent along with reports to the Pharmaceutical (Medical) Registry, for his own archive. Five years later, on August 12, 1725, after a conversation with Vitus Bering in Yeniseysk, he wrote in his journal: “…I showed him my protocols along with the original documents, which contained drawings of things from burial mounds… including those made by myself. When viewing them, Captain Bering advised me to make copies of the drawings, with the help of St. Petersburg artists, and of their descriptions. He warned me that in St. Petersburg they might also demand the things that I bought with my own money, with subsequent reimbursement of the costs, according to the bill presented, and they would definitely take away my journal containing information about the route traveled…” (Putevoy zhurnal…, 2021: 412). V. Bering’s warning turned out to be prophetic.

On January 7, 1728, after his return to St. Petersburg, owing to a conflict with the Archiater J.D. Blumentrost, who headed the Medical Registry, almost all expedition materials of Messerschmidt were arrested and handed over to the Kunstkamera of the newly founded St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences and Arts. The traveler was forbidden under oath to study his own collections and publish descriptions and drawings of “curious things” (Materialy…, 1885: 288–290, 296–297, 347–349, 374–375, 382–384; Tunkina, Savinov, 2017: 135–137). Thereby, the Kunstkamera was supplemented with a large number of “amazing antiquities”, most of which burned down in the catastrophic fire on the night of December 5, 1747. Both the Königsberg scholar G.S. Bayer, the first academician-historian and sinologist of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, and the captured Swedish Captain Philip Johan Tabbert von Strahlenberg (1677–1747), a companion during the first stage of D.G. Messerschmidt’s expedition, initiated publication of a number of archaeological artifacts discovered by Messerschmidt. The latter became the closest assistant to Messerschmidt and, on behalf of the doctor, kept the expedition journal from March 1, 1721 to May 28, 1722. Ph.J. von Strahlenberg invited a Livonian nobleman Karl (Carl) Gustav von Schulmann (1702– 1765), a 20-year-old native from Narva, to take on the drawing duties for the expedition. In the beginning of January 1722, they carried out “winter” excavations of a burial mound on the Yenisey, the results of which were examined by Messerschmidt (Tunkina, Savinov, 2017: 87–90). As D.G. Savinov established, visual materials produced by Messerschmidt strikingly differ in the manner of execution from the drawings of the expedition drawer K.G. von Schulmann, who returned to his motherland in May 1722. The drawings by Messerschmidt are lighter, made with thin lines, without an emphasized contour, with hatching and fine oblique grid, sometimes with the designation of the cardinal points. The drawings by K.G. von Schulmann are made with confident clear lines, without hatching, with designation of the contour of the image, with the volume rendered by shading, and with fractures on the rocks depicted by torn lines thinning at their ends (Ibid.: 120, 121).

Archaeological sites of the Urals and Siberia in archival documents

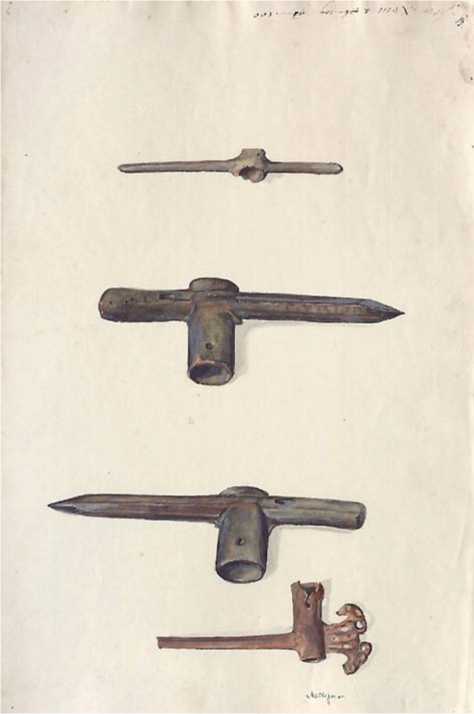

Today archival documents are the only source for reconstructing the archaeological collection of D.G. Messerschmidt. Visual records of the artifacts of Siberian archaeology are available in the five volumes of Messerschmidt’s handwritten journals, individual files of his personal papers, which include illustrated appendices of reports to the Pharmaceutical (Medical) Registry, and in his handwritten work summarizing the results of the expedition, entitled “Sibiria Perlustrata” (“Opisaniye Sibiri”, 1727; facsimile ed.: (Messerschmidt, 2020)). The same artifacts are depicted in watercolor pictures of the Kunstkamera exhibits (Fig. 1), made in the 1730s–1760s by masters and apprentices of the Drawing Chamber at the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences (“Narisovanniy muzey”…, 2003–2004; The Paper Museum…, 2005). The artistic quality of many of the drawings leaves much to be desired. Starting in 1742, the masters of the Engraving Chamber at the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences began to engrave images of the Kunstkamera exhibits on copper and print test prints of engravings. One set was bound, handed over to the Imperial Archaeological Commission, and received the name “Academic Atlas” in the archaeological literature (NA IIMK. R. I, Inv. 1, D. 1231). Watercolor drawings and engravings made from them were supposed to illustrate two unpublished books—a catalog of “curiosities” of the museum (in 1741, only a text catalog of “man-made” artifacts of

Fig. 1 . Unknown artist. Bronze pickaxes of the Tagar culture from the Minusinsk Basin (No. 1, 5th–4th centuries BC; No. 2 and 3, 7th–6th centuries BC; No. 4, 3rd–2nd centuries BC). Collection of D.G. Messerschmidt. Watercolor drawing depicting the exhibits of the Kunstkamera. Watercolor, brush, pen. 1730s. ©St. Petersburg Branch of the Archive of RAS. R. IX, Inv. 4, D. 287, fol. 1.

the Kunstkamera was published (Musei…, 1741)) and “Monumenta Sibiriae” (“Monuments of Siberia”). They were not published due to destruction of most of the artifacts and engravings with their images in the catastrophic fire in the Kunstkamera in 1747. In 1750, 25 separate sheets of engravings were put on sale, which already by the early 19th century were considered to be very rare (Spitsyn, 1906: 235, n. 1; Rudenko, 1962: 10; “Narisovanniy muzey”…, 2004: II). However, many of the engravings greatly misrepresented the depicted objects, because part of the blocks were engraved not from the originals, but from the drawings made by academic artists.

Comparative source analysis of the descriptions and drawings of artifacts surviving in the documents has made it possible not only to reconstruct the part of Messerschmidt’s collection, which ended up in the Kunstkamera (Kopaneva, 2006, 2012), but also to clarify the circumstances of discovering a number of objects, and to establish their cultural and historical attribution (Tunkina, Savinov, 2017: 78–115, pl. I–XVI; Savinov, Tunkina, 2018, 2022).

Messerschmidt regularly reported to the Pharmaceutical (Medical) Registry headed by Archiater J.D. Blumentrost, the elder brother of the first President of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences L.D. Blumentrost, on the progress of his expedition. Three out of 22 reports had illustrated appendices: the fourth (June 25, 1720) from Tobolsk, tenth (May 20, 1722) from Krasnoyarsk, and fourteenth (February 15, 1724) from Irkutsk. Appendices of the fourth and tenth reports have some relation to archaeology.

According to the terms of the Peace of Nystad in 1721, Messerschmidt’s companions Ph.J. Tabbert and K.G. von Schulmann, like other captured Swedish and German officers (“Carolins”) exiled to Siberia, were allowed to return to their homeland. The tenth report of May 20, 1722 by Messerschmidt to the Medical Registry and its appendix with drawings were delivered to St. Petersburg and copied for his own purposes by Tabbert, who then returned to Sweden, for a book he intended to publish on Siberia. In 1737, the archive and library of Ph.J. von Strahlenberg were burned in a fire in his house in Stockholm. The travel journal where he took travel notes during his journey throughout Siberia, and a number of drawings made in the field had already been lost before the incident (Strahlenberg, 1730: 411). They probably included the plan of the burial mound excavated in January 1722 on the banks of the Yenisey, which was known to have been made from the text of the expedition journal. Therefore, the letters of Ph.J. von Strahlenberg (Tabbert) to the prominent figure of the Swedish Enlightenment Erik Benzelius the younger (1675–1743) (Tunkina, 2020a, b) and to the botanist and Doctor of Medicine Johann Philipp Breyne (1680–1764), owner of the famous Cabinet of Naturalia in Danzig, who recommended Messerschmidt to Peter the Great for service (Tunkina, Savinov, 2017: 20–24, 36, 42, 61, 65), are of significant value. The drawings copied from the originals by K.G. von Schulmann, rendering stone statues, Orkhon-Yenisey written records, and Siberian rock art representations discovered by Messerschmidt and Tabbert have survived in appendices of the letters of Ph.J. von Strahlenberg in 1724 in Linköping (Sweden) and Gotha (Germany) (Lehfeldt et al., 2021: Fig. 3–8; Bondar et al., 2022: Fig. 2–3). Ph.J. von Strahlenberg published the images of artifacts that were discovered with his participation in the form of engravings from the originals made by K.G. von Schulmann (Strahlenberg, 1730: Pl. II, V, c, d, VIIIB, XI, XII, XX).

The search for the original reports of Messerschmidt and their appendices in the collection of the Medical Registry in the Russian State Archive of Ancient Acts was unsuccessful. Only the documents which survived in the academic archive under the personal papers of Messerschmidt are available (Tunkina, 2017). The releases of appendices of reports with some (by far not all!) drawings have come down to us. Visual records of a number of archaeological and epigraphic artifacts of the Urals and Siberia mentioned in the documents, in Latin or German annotations of the traveler from the descriptions of appendices of reports, and in the third volume of “Sibiria Perlustrata” are missing (Tunkina, 2021: 267–269).

Field journals of the expedition, published in East Germany in an incomplete form along with individual drawings, mention a number of ancient monuments seen by Messerschmidt (1962–1977). For example, the journal includes sketches of the Ust-Es Kys-Tash and Kurtuyak-Tash stone statues of the Okunev culture of the Bronze Age (16th–14th centuries BC), discovered by the traveler on August 18, 1722, drawn with the Rhine fortification scale, as well as drawings of the now lost burial mound slabs of the Saragash stage of the Tagar culture of the 5th–3rd centuries BC in the Es-Teya-Abakan steppes. The drawing of the Turkic stone anthropomorphic statue “Daurian kurtuyak” in the Argun steppe (described in the journal in the entry on September 14, 1724) escaped the attention of scholars for three hundred years (Tunkina, 2019: Fig. 6). Handwritten journals and appendices of reports contain sketches of the Tom, Novoselovo, and Biryusa rock art sites, and the “Painted Stone” on the right bank of the Angara River, near the village of Klimovaya, etc. (Tunkina, Savinov, 2017: Pl. XIV, 4, 5; XV).

Messerschmidt attached to his fourth report of June 25, 1720 from Tobolsk a “philological sample from the Fetka caves on the cliff”—drawings of petroglyphs from the Irbit rock art site in the Middle Urals, which Messerschmidt believed to be an unknown script. They are represented by copies of drawings made in 1703 by S.U. Remezov and his son Leonty taken from Remezov’s “Service Book”, which were made by someone for Messerschmidt in Tobolsk. Another “sample” included “ancient grave goods, shaitans, figurines adorned with precious stones, coins, and so on and so forth”, which, in the opinion of the traveler, were meant to clarify the dark history of the Siberian peoples. Messerschmidt assembled his collection of artifacts at his own expense, and sent the first parcel of antiquities in a “safely sealed” box to St. Petersburg to the Archiater J.D. Blumentrost, together with the fourth report (Perviy issledovatel…, 2019: 260). We may have some idea of the “sample” that included antiquities from the surviving list of the plates; however, only two plates—a plan of Kungur Cave and a drawing of a Western European aquamanale in the shape of a knight—have survived out of nine illustrative appendices in Messerschmidt’s personal papers (Fig. 2).

Illustrated appendices of the tenth report of Messerschmidt of May 20, 1722 from Krasnoyarsk

Fig. 2 . Unknown artist. Bronze aquamanale in the shape of a mounted knight. Hildesheim, Lower Saxony. Ca 1200 or the early 13th century. ©St. Petersburg Branch of the Archive of RAS. F. 98, Inv. 1, D. 20, fol. 50.

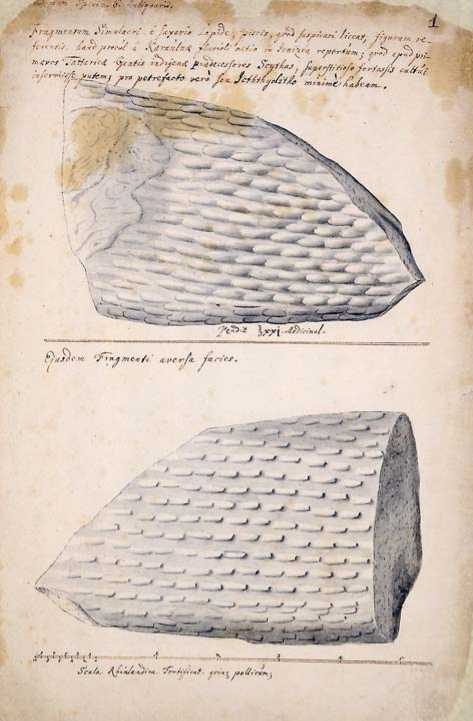

included both “philological examples” (petroglyphs) and “examples of antiquities” (archaeological artifacts), as well as “philological antiquities” (stone statues with Orkhon-Yenisey runic writings discovered by the traveler). These contain a drawing by K.G. von Schulmann representing a stone object 15–20 cm in size, which was found at the mouth of the Karaulnaya River, at its confluence with the Yenisey (Fig. 3). According to L.R. Kyzlasov, it was an image of a fish-bait from the Serov stage of the Baikal Late Neolithic culture (late 4th to mid 3rd millennium BC) (1962: 51). However, it is possible that the drawing depicted a fragment of a lepidodendron, or scale tree fossil—an extinct tree-like lycopsid plant of the forests of the Carboniferous Period. Fossil specimens show imprints from the bases of fallen leaves on the trunk and branches of this plant, which form “cushions” resembling scales of a fish, snake, or alligator.

In St. Petersburg, at the end of 1727, Messerschmidt compiled his handwritten three-volume final work “Sibiria Perlustrata” (“Description of Siberia”), which

Fig. 3 . K.G. von Schulmann. Fragment of a stone statue of a Neolithic fish-bait, or fragment of a lepidodendron (scale tree) fossil. ©St. Petersburg Branch of the Archive of RAS.

F. 98, Inv. 1, D. 37, fol. 1.

he dedicated to the young Emperor Peter II. The monograph summed up the Siberian journey not only in terms of natural scientific knowledge. The third volume of the manuscript “Philologico-Historico-Monimentario et Antiquario-Curiosus” (“Philological and Historical, Related to Artifacts and Curious Antiquities”) (SPbF ARAN. F. 98, Inv. 1, D. 22, fols. 327–393) (Messerschmidt, 2020: Fols. 327–393) contains a subsection “Curiosa Sibiriae Monimentaria” (“Curious Artifacts of Siberia”) (Ibid.: Fols. 334–393). The manuscript “Description of Siberia” is preceded by a list of plates planned for publication, “Idea Operis cum serie iconum opera suis locis inseredarum” (“The Idea of the Work with a Series of Images…”) (Ibid.: Fols. 12–14v, No. 68–124). A separate subsection of the list is entitled “XI. Antiquitatis hactenus ignoratae Monimenta Sibirica, iconismis aliquot seqq. repraesentata” (“Hitherto Unknown Siberian Antiquities Represented in Several of the Following Images”). The plates related to archaeology have the author’s headings

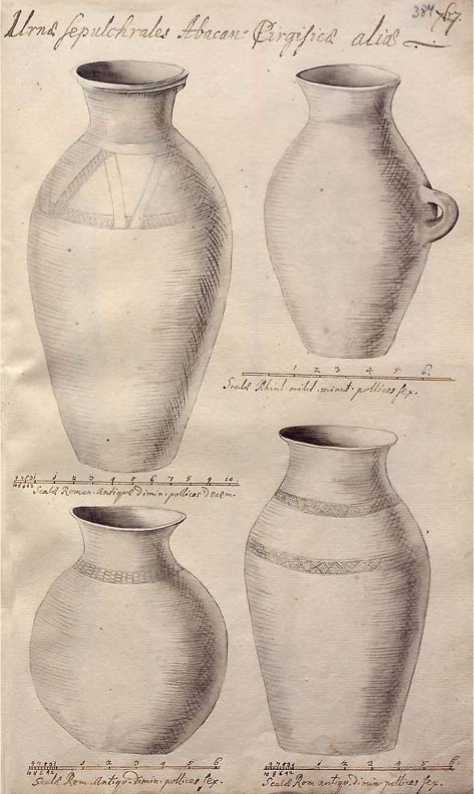

(Fig. 4), but the manuscript contains only 36 drawings with the author’s explanations; twenty two sheets were left blank for drawings with annotations and references to the images from the appendices of the fourth (1720) and tenth (1722) reports to the Medical Registry, that is, to the initial stage of the Messerschmidt’s journey, when the expedition explored the environs of Tobolsk and the Minusinsk Basin. This subsection of the third volume consists of brief annotations to the drawings of Siberian archaeological artifacts (stone statues, burial mounds, petroglyphs, grave goods—amulets, vessels, utensils, ornaments, weapons, and horse harnesses) (Savinov, 2021). Contamination of the visual materials and texts of Messerschmidt makes it possible to reconstruct a number of images missing from “Sibiria Perlustrata”.

Fig. 4 . “Abakan-Kyrgyz burial urns” (No. 1, 3, and 4, decorated (so-called “Kyrgyz”) vases, 7th–9th centuries; No. 2, vessel with smooth walls and small vertical handle on the body, 8th–9th centuries). Illustration for the manuscript of “Sibiria Perlustrata” by D.G. Messerschmidt. 1727. ©St. Petersburg Branch of the Archive of RAS. F. 98, Inv. 1, D. 22, fol. 384.

It is known that the artist and engraver, master of map-making and letter-cutting Georg Johann Unverzagt (1701–1767), who traveled with the embassy of L.V. Izmailov to China (1719–1720) and whom Messerschmidt made acquaintance with earlier in 1719, made hand-drawn copies of “many curious things” brought by Messerschmidt to St. Petersburg (Materialy…, 1885: 347, 349, 375, 382, 391, 393–394). It is probable that he was the author of the majority of the highly artistic botanical, zoological, and archaeological illustrations to Messerschmidt’s manuscript, “Sibiria Perlustrata” (2020), which contains only a few single-color line drawings made by the author. Most likely, Unverzagt made his drawings under private commission; for such practices he was subsequently fired from the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences and Arts (Tunkina, 2021: 269).

The literature concerning Messerschmidt often reproduces not the original drawings, but trace drawings of them (Borisenko, Hudiakov, 2005: Fig. 5, 6, 14–20). Many images were previously published in fragments; not from the originals, but from copies from the unpublished album of V.V. Radlov “Original Skitzen einiger Gegenden in Hoch-Asien. Aufgenommen von Dr. W. Radloff auf seiner Reise durch den Altai. 1861” (1861–1918), which is kept in the collection of illustrations in the Department of Archaeology at Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Coll. No. 5041). Out of 75 sheets only a few sheets with medieval artifacts have been published (Korol, 2008: App. 10, pl. VIII, XI, XIII, XVI, XXXIX, XL–XLII). The name of the album was misleading to a number of scholars (including G.G. Korol), who attributed the finds represented in the album exclusively to the Altai. On the contrary, the copied illustrations from Messerschmidt’s “Sibiria Perlustrata”, presented in the form of applications in the album of V.V. Radlov, primarily rendered artifacts from the Minusinsk Basin.

Conclusions

This long-term study, summed up in a monograph (Savinov, Tunkina, 2022), was intended to present all, without any exception, the original drawings of Siberian archaeological artifacts from the collection of D.G. Messerschmidt, with scientific commentary and cultural and historical attribution (Tunkina, 2017; 2019: 48, 49; Savinov, 2021). Field journals, appendices of the traveler’s reports to the Pharmaceutical (Medical) Registry with illustrations, all Latin texts and drawings from the third volume of “Sibiria Perlustrata” related to the archaeology of Siberia, and items from Messerschmidt’s collection preserved in the drawings of the Kunstkamera exhibits were analyzed. The visual evidence has made it possible to evaluate the nature, volume, and chronological range of Messerschmidt’s archaeological collection. The importance of these materials also results from the fact that most of the artifacts perished during the fire in the Kunstkamera on December 5, 1747. Consequently, the texts of the scholar and sketches made during the expedition and after it turn out to be almost the only source allowing us to evaluate the collection as a whole.

One century after the fire in the Kunstkamera, some artifacts from Messerschmidt’s collection, at the request of Emperor Alexander II, were handed over to the Imperial Hermitage in 1859 as a part of the Siberian collection of Peter the Great. However, today it is extremely problematic to identify the items collected by Messerschmidt. In the inventories of the 18th century, only a few artifacts from Peter the Great’s Siberian collection were identified as having been part of the collection gathered by the pioneer of the archaeological study of Siberia.

The main conclusion of this study is that the collection of D.G. Messerschmidt was the first archaeological collection in Russia purposefully compiled during a scholarly expedition, as opposed to the Siberian collection of Peter the Great (about 250 items) or the collection of the Dutchman N. Witsen, which included drawings of about forty things, which fit onto four or five plates of his compilation work “Northern and Eastern Tartaria” (depending on the edition of 1692, 1705, or 1785). Messerschmidt’s collection contained not only highly artistic items made of gold and silver, which were procured in Siberia by grave robbers, but mostly ordinary artifacts (things made of iron or copper (bronze), pottery) reflecting almost the entire range of archaeological cultures of the Minusinsk Basin, from the Bronze Age to the Late Middle Ages, as well as images of petroglyphs and stone statues with signs of writing unknown to science at that time (Savinov, Tunkina, 2022: 11, 15). This is the main difference between the collection of Messerschmidt, together with academicians G.F. Miller and I.G. Gmelin, who followed in his footsteps in the Academic team of the Second Kamchatka Expedition (Zavitukhina, 1978), from the much better known collections of N. Witsen (Radlov, 1888: 3–5; Zavitukhina, 1999) and Peter the Great’s Siberian collection (Spitsyn, 1906; Rudenko, 1962; Zavitukhina, 1977, 2000; Korolkova, 2006, 2012), which consisted mainly of gold and silver artifacts. The attention of Messerschmidt to the characters written on statues and ancient grave goods, which could give a clue to understanding which peoples had left them, was not accidental. Documents confirm that Messerschmidt made it a priority to discover a number of monuments, in particular rock art sites, stone statues, and the Orkhon-Yenisey script of the medieval population of the Minusinsk Basin. The corpus of images proves that at that time Messerschmidt’s collection, which included about 370 artifacts, was the largest and most representative collection of Siberian archaeological artifacts not only in Russia, but also in the whole world.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, Project No. 20-011-42006.

Список литературы D.G. Messerschmidt’s collection of Siberian antiquities in drawings at the St. Petersburg Archive of the Academy of Sciences

- Bondar L.D., Borodaev V.B., Walravens H., Zorin A.V., Lehfeldt W. 2022 Ph.J. Strahlenberg i yego karta Velikoy Tatarii (dva pisma Ph.J. Strahlenberga k J.Ph. Breyne 1723 i 1724 gg.). Kunstkamera, No. 1 (15): 72-98.

- Bondar L.D., Zorin A.V., Tunkina I.V. 2019 “Megaera Tattarica” i drugiye neizdanniye eskizy Danielya Gotliba Messerschmidta. In Collegae, amico, magistro: Sbornik nauchnykh trudov k 70-letiyu Wilanda Hintzsche, V.A. Abashnik, L.D. Bondar, A.-E. Hintzsche (eds.). Kharkov: Maidan, pp. 171-183.

- Borisenko A.Y., Hudiakov Y.S. 2005 Izucheniye drevnostey Yuzhnoy Sibiri nemetskimi uchenymi 18-19 vv., V.I. Molodin (ed.). Novosibirsk: Novosib. Gos. Univ.

- K 300-letiyu nachala ekspeditsii Danielya Gotliba Messerschmidta v Sibir (1719-1727). 2021 I.V. Tunkina (ed.). St. Petersburg: Renome. (Ad Fontes: Materialy i issledovaniya po istorii nauki; iss. 19).

- Kopaneva N.P. 2006 Messerschmidt’s archaeological collection comes back. Science First Hand, No. 6 (11): 54-61.

- Kopaneva N.P. 2012 Die Rekonstruktion der Sammlungen der Kunstkamera in Sankt Petersburg am Beispiel der archäologischen Sammlungen von Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt. In Die Erforschung Sibiriens im 18. Jahrhundert: Beiträge der Deutsch-Russischen Begegnungen in den Franckeschen Stiftungen, W. Hintzsche, J.O. Habeck (eds.). Halle: Verlag Frankeschen Stiftungen zu Halle, pp. 87-98.

- Korol G.G. 2008 Iskusstvo srednevekovykh kochevnikov Yevrazii: Ocherki. Kemerovo: Kuzbassvuzizdat.

- Korolkova E.F. 2006 Zoloto kochevnikov: O “Sibirskoy kollektsii” Petra I. Nauka iz pervykh ruk, No. 5 (11): 60-71.

- Korolkova E.F. 2012 Sibirskaya kollektsiya Petra I v Ermitazhe. In Scripta antiqua: Voprosy drevney istorii, fi lologii, iskusstva i materialnoy kultury, vol. 2. Moscow: Lyubimaya Rossiya, pp. 329-354.

- Kyzlasov L.R. 1962 Nachalo sibirskoy arkheologii. In Istoriko-arkheologicheskiy sbornik k 60-letiyu A.V. Artsikhovskogo, D.A. Avdusin, V.L. Yanin (eds.). Moscow: Izd. Mosk. Gos. Univ., pp. 43-52.

- Lehfeldt W. 2023 Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt, 1685-1735: Der erste Erforscher Sibiriens. Versuch einer Annä herung an einen großen Wissenschaftler. Unter Mitwirkung von L.D. Bondar’, M. Knü ppel. Gö ttingen: Universitätsverlag. (In press).

- Lehfeldt W., Knüppel M., Tunkina I.V., Elert A.K. 2021 Pismo Ph.J. von Strahlenberga E. Benzeliusu Mladshemu o narodakh i drevnostyakh Sibiri. In K 300-letiyu nachala ekspeditsii Danielya Gotliba Messerschmidta v Sibir (1719- 1727), I.V. Tunkina (ed.). St. Petersburg: Renome, pp. 119-142. (Ad Fontes: Materialy i issledovaniya po istorii nauki; iss. 19).

- Materialy dlya istorii Imperatorskoy akademii nauk. 1885 M.I. Sukhomlinov (comp. and ed.). In 10 vols. Vol. 1: 1716-1730. St. Petersburg: [Tip. Imp. AN].

- Messerschmidt D.G. 1962-1977 Forschungsreise durch Sibirien. 1720-1727, E. Winter, G. Uschmann, G. Jarosch (eds.). Vol. 1: Tagebuchaufzeichnungen 1721-1722. Vol. 2: Tagebuchaufzeichnungen Januar 1723-Mai 1724. Vol. 3: Tagebuchaufzeichnungen Mai 1724-Februar 1725. Vol. 4: Tagebuchaufzeichnungen Februar 1725-November 1725. Vol. 5: Tagebuchaufzeichnungen ab November 1725. Berlin: Academie Verlag.

- Messerschmidt D.G. 2020 Sibiria Perlustrata, etc.: Faksimilnoye izdaniye rukopisi, I.V. Tunkina (project head). St. Petersburg: Kolo.

- Musei Imperialis Petropolitani. 1741 Vol. 2. Ps. 1: Qua continentur res artifi ciales. St. Petersburg: Typis Academiae Scientiarum Petropolitanae.

- “Narisovanniy muzey” Peterburgskoy Akademii nauk. 1725-1760. 2003-2004 R.E. Kistemaker, N.P. Kopaneva, D.J. Meijers, G.V. Vilinbakhov (eds.). In 2 vols. St. Petersburg: Yevropeiskiy dom.

- Novlyanskaya M.G. 1970 Daniil Gotlib Messerschmidt i yego raboty po issledovaniyu Sibiri. Leningrad: Nauka.

- Perviy issledovatel Sibiri D.G. Messerschmidt: Pisma i dokumenty. 1716-1721. 2019 E.Y. Basargina, S.I. Zenkevich, V. Lehfeldt, A.L. Khosroev (comp.); E.Y. Basargina (ed.). St. Petersburg: Nestor-Istoriya. (Ad Fontes: Materialy i issledovaniya po istorii nauki; suppl. 7).

- Putevoy zhurnal Danielya Gotliba Messerschmidta: Nauchnaya ekspeditsiya po Yeniseyskoi Sibiri: 1721-1725 gody. 2021 G.F. Bykonya, I.G. Fedorov, Y.I. Fedorov (transl., comp., comm.). Krasnoyarsk: Rastr.

- Radlov V.V. 1888 Sibirskiye drevnosti, vol. I (1). St. Petersburg: [Tip. Imp. AN]. (MAR; No. 3).

- Rudenko S.I. 1962 Sibirskaya kollektsiya Petra I. Moscow, Leningrad: Izd. AN SSSR. (SAI; iss. D3-9).

- Savinov D.G. 2021 Kulturno-khronologicheskaya atributsiya risunkov pamyatnikov arkheologii iz rukopisi D.G. Messerschmidta “Sibiria Perlustrata”. In K 300-letiyu nachala ekspeditsii Danielya Gotliba Messerschmidta v Sibir (1719-1727), I.V. Tunkina (ed.). St. Petersburg: Renome, pp. 252-265. (Ad Fontes: Materialy i issledovaniya po istorii nauki; iss. 19).

- Savinov D.G., Tunkina I.V. 2018 “Tesinskiy bogatyr”: Vozvrashcheniye k originalu. Stratum plus, No. 6: 29-51.

- Savinov D.G., Tunkina I.V. 2022 Sibirskaya kollektsiya D.G. Messerschmidta - pervoye nauchnoye arkheologicheskoye sobraniye Rossii, I.V. Tunkina (comp., ed.); with participation of A.V. Zorin, K.V. Kravtsov, A.A. Sizova, D.G. Mukhametshin, E.F. Korolkova; M.V. Ponikarovskaya and W. Lehfeldt (transl. from Latin and French). St. Petersburg: Renome. (Ad Fontes: Materialy i issledovaniya po istorii nauki; suppl. 11).

- Spitsyn A.A. 1906 Sibirskaya kollektsiya Kunstkamery. Zapiski Otdeleniya russkoy i slavyanskoy arkheologii Imperatorskogo Russkogo arkheologicheskogo obshchestva, vol. VIII (1): 228-248.

- Strahlenberg Ph.J., von. 1730 Das Nord- und Östliche Theil von Europa und Asia, etc. Stockholm: [s.p.].

- The Paper Museum of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, c. 1725-1760: Introduction and Interpretation. 2005 R.E. Kistemaker, N.P. Kopaneva, D.J. Meijers, G.V. Vilinbakhov (eds.). Amsterdam: Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

- Tunkina I.V. 2017 Pamyatniki arkheologii Sibiri v dokumentakh lichnogo fonda D.G. Messerschmidta. In Universitetskaya arkheologiya: Proshloye i nastoyashcheye. Materialy Mezhdunarodnoy nauchnoy konferentsii, posvyashchennoy 80-letiyu pervoy v Rossii kafedry arkheologii. 19-21 oktyabrya 2016 g., SanktPeterburg, I.L. Tikhonov (ed.). St. Petersburg: Izd. SPb. Gos. Univ., pp. 234-239.

- Tunkina I.V. 2019 Arkheologiya Sibiri v dokumentakh D.G. Messerschmidta. Vestnik RFFI: Gumanitarniye i obshchestvenniye nauki, No. 3: 45-61.

- Tunkina I.V. 2020a Materialy ob ekspeditsii D.G. Messerschmidta v pismakh Ph.J. Strahlenberga E. Benzeliusu-mladshemu. In Aktualniye problemy otechestvennoy istorii, istochnikovedeniya i arkheografi i: K 90-letiyu N.N. Pokrovskogo, A.P. Derevianko, A.K. Elert (eds.). Novosibirsk: Inst. istorii SO RAN, pp. 305- 309. (Arkheografi ya i istochnikovedeniye Sibiri; iss. 39).

- Tunkina I.V. 2020b Pisma Ph.J. Strahlenberga E. Benzeliusu Mladshemu - noviy istochnik ob ekspeditsii D.G. Messerschmidta v Sibir. In Trudy VI (XXII) Vserossiyskogo arkheologicheskogo syezda v Samare, A.P. Derevianko, N.A. Makarov, O.D. Mochalov (eds.), in 3 vols. Vol. III. Samara: Samar. Gos. Sots.-Ped. Univ., pp. 154-156.

- Tunkina I.V. 2021 Pamyatniki arkheologii Sibiri v risunkakh ekspeditsii D.G. Messerschmidta i G.F. Millera. In K 300-letiyu nachala ekspeditsii Danielya Gotliba Messerschmidta v Sibir (1719- 1727), I.V. Tunkina (ed.). St. Petersburg: Renome, pp. 266-272. (Ad Fontes: Materialy i issledovaniya po istorii nauki; iss. 19).

- Tunkina I.V., Savinov D.G. 2017 Daniel Gotlib Messerschmidt: U istokov sibirskoi arkheologii. St. Petersburg: ElekSis. (Ad Fontes: Materialy i issledovaniya po istorii nauki; suppl. 6).

- Zavitukhina M.P. 1977 K voprosu o vremeni i meste formirovaniya Sibirskoy kollektsii Petra I. In Kultura i iskusstvo petrovskogo vremeni: Publikatsii i issledovaniya. Leningrad: Iskusstvo, pp. 63-69.

- Zavitukhina M.P. 1978 Kollektsiya G.F. Millera iz Sibiri - odno iz drevneishikh arkheologicheskikh sobraniy Rossii. Soobshcheniya Gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha, iss. 43: 37-40.

- Zavitukhina M.P. 1999 N.K. Witsen i yego sobraniye sibirskikh drevnostey. ASGE, iss. 34: 102-114.

- Zavitukhina M.P. 2000 Petr I i Sibirskaya kollektsiya Kunstkamery. In Iz istorii petrovskikh kollektsiy: Pamyati N.V. Kalyazinoy. St. Petersburg: Izd. Gos. Ermitazha, pp. 14-26.