“D.G. Messerschmidt’s cups”

Автор: Mitko O.A.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.51, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

We describe two metal vessels, procured by looters and offered to D.G. Messerschmidt, who in 1722 traveled across southern Krasnoyarsk Territory. A bronze cup, judging by a description in researcher's journal and by the accompanying drawing, resembled Old Turkic specimens. However, the hunting scene engraved on its body suggests Chinese provenance. A silver vessel from the vestry of Fort Karaulny church is peculiar to 7th–10th century Sogdian toreutics. It evidently belongs to a group of vessels with polygonal bodies, specifi cally to type 1—octagonal. Having been manufactured in Sogd, polygonal vessels were exported to China. Chinese jewelers copied the form of “wine cups” and adorned them with traditional fl oral designs and various scenes. An octagonal silver cup with an Uyghur inscription, found in 1964 in a kurgan at a medieval cemetery Nad Polyanoi, was likewise manufactured by Tang artisans. Other polygonal silver cups are listed—heptagonal and sexagonal. It is concluded that vessels made of precious metals testify to stable trade relations that emerged in 700–1100 and connected Siberia with Sogd and the Tang Empire.

Altai-Sayan, Tang Age, Kyrgyz, Sogdians, octagonal cup, large metal vessels

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146826

IDR: 145146826 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2023.51.1.138-145

Текст научной статьи “D.G. Messerschmidt’s cups”

300 years ago, studies of large pieces of medieval toreutics of Southern Siberia began with a drawing of two metal vessels. In 1722, D.G. Messerschmidt traveled through the valleys of the Yenisey and Abakan rivers, and had the opportunity to purchase “rare” items from the local kurgan-looters. However, owing to lack of funds, he sometimes was not able to buy anything, as was the case with two silver cups. Today, only brief descriptions in journals and graphic images made by Messerschmidt and his companions provide us with information about these ancient rarities. The drawings differ in their technique and accuracy of representation of individual details. These sketches can be used as sources for studying various issues of medieval history and archaeology, for instance, identification of tribal nobility, only through a comparative analysis of these images with similar finds from other regions.

The history of discovery of the vessels and their description

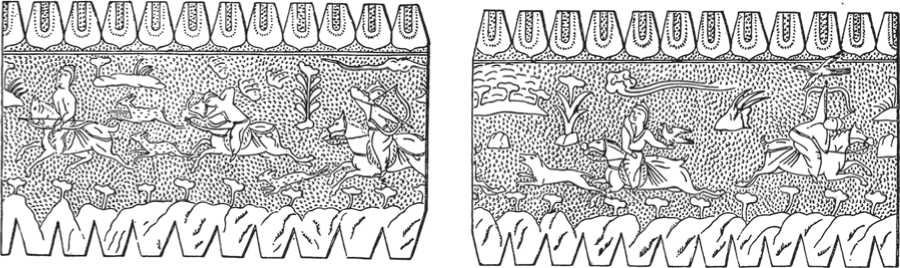

Information about one of the two cups has survived in the form of a brief description and two graphic images. In the scientific literature, this item is known under different names, which causes difficulties not only with its typological definition, but with cultural attribution in general (Fig. 1).

In October 1722, Messerschmidt wrote in his journal that he stayed in Krasnoyarsk, at the apartment of “a nobleman, Ilya Nashivishnikov-Surikov”. As the researcher noted, after lunch a kurgan-looter (another Ilya) arrived, “and offered me to buy a beautiful jug with silver coins, on which a very nice leaf ornament was engraved, [weighing] 67 zolotniks; he asked for 12 kopecks for a zolotnik, which in total amounted to 8 rubles and 4 kopecks. I offered him 7 kopecks for

Fig. 1. “Silver bowl from Yenisey”.

1 – cup drawing published by V.V. Radlov (1891: Pl. III, IV]; 2 – tracing of the image engraved thereon (Korol, 2008: Pl. 15). The scale is not specified.

a zolotnik, 4 rubles and 69 kopecks in total. He did not want to bargain for a jug, and I had to let him go for lack of salary and money, in the hope that maybe at another time he could sell cheaper” (2012: 157). It was noted in the literature that Messerschmidt acquired ancient rarities but rarely indicated their provenance in his records; the vessel in question was not properly annotated either (Tunkina, Savinov, 2017: 82). Captain P. Tabbert (Strahlenberg), a member of Messerschmidt’s expedition, designated the “jug” as an “urn”; Radlov, in his work of 1861, named the item a “bronze vessel” (see (Korol, 2008: 133, pl. 15, B )), while in his publication of 1891 a “silver bowl from the Yenisey” (1891: Pl. III, F ; IV A , C ). In the monograph by L.A. Evtyukhova, the caption to the image of the item states: “Silver cup of Messerschmidt” (1948: Fig. 85).

The history of this vessel is quite well described by G.G. Korol (2008). It notes that the two sketches show significant differences in the shape of the vessel and its ornament. Having analyzed the word-for-word translation of an excerpt from Messerschmidt’s journal, Korol came to the conclusion that the researcher did not know the exact place where the looter found this “apparently bronze item”. She believed that judging by the scenes of hunting with a hunting bird, framed with vegetable and landscape motifs (Fig. 1, 2), the vessel could have been made in the Tang Empire, China (Korol, 2008: 133). In its morphological characteristics, it is close to the group of ancient Turkic mug-type vessels; but unlike the latter, it is decorated with a scene covering its entire surface, and does not have a base nor a handle. Among the described items of the Tang tableware, no parallels to the “silver bowl from the Yenisey” have been identified, although hunting motifs with scenes of riding and archery appeared in Chinese ornamentation as early as the previous periods of the Northern and Southern dynasties and are associated with the Middle Eastern artistic tradition of the Six Dynasties.

On February 19, 1722, several copper items from the “kurgans” of the Middle Yenisey were brought to Messerschmidt, who arrived with his companions from the village of Sisim at Fort Karaulny (Verkhny). As Stralenberg noted, these items included “a very old silver cup with a handle”, which Messerschmidt ordered someone to draw. “Mister doctor really wanted to buy this cup, but the owner was absent, and they said that the cup was pledged in the church” (Messerschmidt, 1962: 182–183). The doctor instructed the sexton to tell the owner to bring the vessel to Krasnoyarsk, where he could “give good money” for it (Messerschmidt, 2012: 39–40). The cup hasn’t survived; however, according to N.P. Kopaneva, it was nevertheless brought to Krasnoyarsk and bought by Messerschmidt. This is

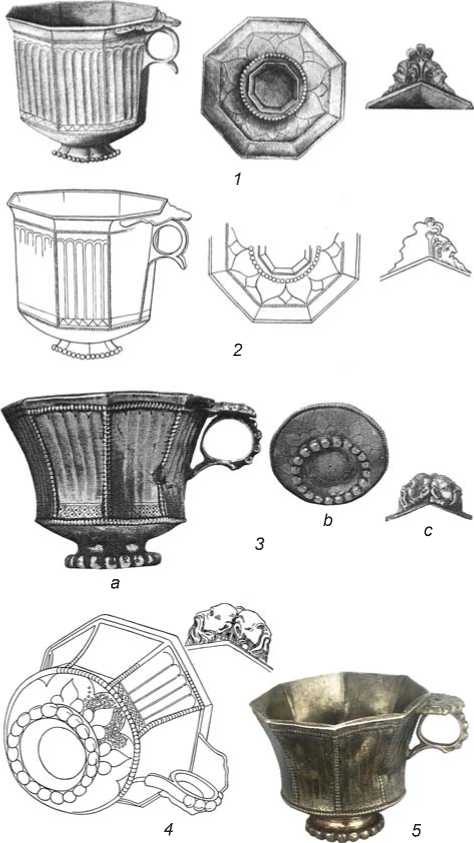

Fig. 2. Octagonal cups.

1 – drawing of the cup from the vestry of Fort Karaulny church (Smirnov, 1909: Pl. XLVIII, 115); 2 – tracing of the cup from the vestry of Fort Karaulny church (Marshak, 1971: Pl. 14); 3 – cup from the Perm Governorate (Smirnov, 1909: Pl. XLVIII, 114);

4 – tracing of the cup from the Perm Governorate (Marshak, 1971: Pl. 26); 5 – photo of the cup from the Perm Governorate (©State Hermitage, St. Petersburg). The scale is not specified.

confirmed by the fact that the drawings in three planes were made in St. Petersburg by a professional artist and included in the album “Sibiria perlustrata” (Fig. 2, 1 , 2 ) (Kopaneva, 2006: 78).

Parallels to the vessels

An almost complete parallel to the silver vessel from the vestry of Fort Karaulny church is a cup found in the Krasnoufimsky Uyezd, Perm Governorate (Fig. 2, 3–5). This similarity was noted by Y.I. Smirnov, who included the images of both cups in the atlas of oriental silver (1909: Pl. XLVIII, 114, 115). In our viewpoint, the distinguishing features of cups of this type are not only the polygonal shape of the vessel’s body, but also the paired image of the faces of bearded men on the horizontal shield of the handle.

Both cups belong to the group of vessels with a polygonal body on a low base and with a ring-shaped handle, type 1 – octagonal (octahedral), variant 1 – cylindrical shape with fluted edges and a handle decorated with anthropomorphic heads. Researcher of the Tang metal tableware Bo Gyllensvärd noted that cups with polygonal bodies find prototypes among Sasanian vessels (“wine cups”) (1957: 63–64). On the basis of analysis of the influence of the artistic traditions of the steppe world and the artistic techniques and subjects typical of the urban culture of Central Asia and the Middle East on the toreutics made of Chinese craft centers, he singled out a group of vessels with hexagonal and octagonal bodies (Ibid.: Fig. 24, a–d ). B.I. Marshak believed that the shape and motifs of the decor made it possible to date the Yenisey cup reliably to the second half of the 7th century, and the Perm cup to the turn of the 7th–8th centuries. He associated both vessels with a separate craft school (“C”) of the Sogdian craftsmen of the 7th–10th centuries, the time when Sogdian and Sasanian techniques merged in the workshops of this school (Marshak, 1971: 28–29, 47, pl. 14, 26).

Variant 2 of the same type—octagonal (octahedral)— includes small cups with the dimensions standard for polyhedral vessels: height 6–7 cm, width in the upper part 6–9 cm, with an expanding rim and a low conical base. Their characteristic feature is the facets richly decorated with floral designs or various scenes with images of people, animals, and insects. The images are made through engraving and punching techniques. The catalogs of European and American private collections, museum collections, and auctions provide descriptions and photographs of octagonal silver vessels of the Tang and Liao periods, called “flowers and bird” (Fig. 3, 1 ); these are decorated with a large image of a fantastic bird among twining foliage, and have a looped handle in the shape of a trefoil (Fig. 3, 2 ).

The facets of a silver gilded cup from the Metropolitan Museum of Art are decorated with floral motifs, applied over a chased background. The ring-handle with a horizontal shield and the bottom part of the cup also bear floral motifs in the form of shoots, palmettes, and small and large flowers (Fig. 3, 3 ).

In the Middle Yenisey, the only cup of variant 2 was discovered in 1964 in the tomb of the Nad Polyanoi cemetery, near the village of Bateni (Fig. 4, 1 ). Its facets bear the images of a phoenix, an animal with lion’s paws and a wide tail, a running animal resembling a fox, and two fallow deer; the fragment of handle contains the

Fig. 3. Octagonal silver cups.

1 – cup decorated with floral design (Michael, 1991: Pl. 21); 2 – “Phoenix” cup (Gyllensvärd, 1953: No. 104); 3 – cup from the Metropolitan Art Museum (E. Erickson Foundation; . The scale is not specified.

Fig. 4. Octagonal cups.

1 – cup from the Nad Polyanoi cemetery (©State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg); 2 – gilded silver cup with images on the walls, from a private collection (photograph by S.G. Narylkov); 3–5 – cups from the tomb of the Liao dynasty at Turji Mountain in Tongliao City (photographs by S.G. Narylkov); 6 – gilded cup from a shipwreck at Belitung Island, Indonesia (Worrall, 2009: 116); 7 – cup from the Hejia village, Xi’an, Shaanxi (photo by S.G. Narylkov); 8 – cup from the Hejia village, Xi’an, Shaanxi (Hansen, 2003: Fig. 5, 1 ); 9 – cup from the Hejia village, Xi’an, Shaanxi (Li Laiyu, 2014: Fig. 1).

image of a butterfly or a bee. A.A. Gavrilova dated the cup to the late 9th–early 10th centuries and argued that its shape was close to that of a charka ‘goblet’ (1968: 26, 29). Notably, the use of the word charka in the Russian-language classification of medieval oriental ware made of precious metals to designate a group of vessels having such a small size and shape is quite appropriate. As M. Vasmer noted, according to one version, the word chara is associated with the Indo-European linguistic layer (carus ‘cauldron’, ‘sacrificial bowl’, ‘pot’, and even ‘skull’), according to another, it is a borrowing from the Turkic and Altai languages (cara ‘big bowl’) (1987: 316). Along the edge of the base, there is an engraved inscription representing an early type of Uyghur writing of the 8th–11th centuries. One version of its translation reads: “Holding a sparkling bowl, I fully (or: I, Tolyt) found happiness” (Shcherbak, 1968).

All available parallels to this vessel are associated with China, where faceted gold vessels were common in the Tang Dynasty period (Fig. 4, 2–5 ). Most often, such vessels had seven or eight facets, which were either decorated with sophisticated scenes or ornamental patterns, or remained smooth. According to Gyllensvärd, the prototypes of Chinese products were Sasanian vessels (1957: Fig. 24).

Abundant Tang artistic products discovered in 1998 aboard the shipwreck close to the western coast of Belitung Island in the Java Sea provide significant information about trade and economic relations and routes along which silver and gold or gilded cups bearing various scenes were distributed. Most likely, the ship was transporting a large number of mass-produced products to the Middle East. A richly decorated octagonal vessel from a set of silver and gold tableware found in the shipwreck was dated to a period no earlier than the 8th century (Fig. 4, 6) (Louis, 2011).

Noteworthy are the octahedral cylindrical mugs that were part of the Hejiacun hoard, and those discovered in the Hejia village, Xi’an (Fig. 4, 7–9). Like the vessel from the shipwreck, their facets are decorated with sculptured figures of musicians and dancers, which represent Sogdian motifs in Chinese art. The depicted humans have deep-set eyes and protruding noses, and bear pointed or corrugated headdresses on their heads. On the basis of analysis of more than 30 similar items, Chinese researcher Qi Dongfang inferred that these do not belong to the traditional Chinese tableware and can be subdivided into three groups: vessels imported from Sogd; vessels made by Sogdian craftsmen in China; and vessels made by Chinese craftsmen in China “under Sogdian influence” (1998). The proposed classification is based on variations in the shape of only one element—handles; although, in our opinion, a detailed typology should also take into account the morphological features of other vessel parts. Some researchers argue that production of vessels with ring handles is typical of the period of the highest economic and political stability of the Tang Dynasty. Decoration of the body with ornaments with relief figures became a technological and artistic innovation of vessels in that time (Kieser, 2015: 63; Szmoniewski, 2016: 237– 238, fig. 1).

The heptagonal (seven-sided) and sexagonal (hexagonal) vessels make up special types of polygonal cups.

Heptagonal cups are represented by one variant. Two such cups have been found at Liao Dynasty sites in Inner Mongolia. One of them (Fig. 5, 1 ) was discovered during excavations of the grave of a major Khitan official of the ruling dynasty Yelü Yuzhi (890–941) (Du Hanchao, 2014). The cups, slightly over 6 cm high, with diameters of the mouth over 7 cm, were made of silver sheet with full gold cover produced by fire-gilding. Their features are a low wide stem decorated with a floral ornament with small “pearls”, and a handle in the form of a horizontal shield and a small hook instead of a ring. The facets bear engraved figures of sitting elders framed by bamboo branches and leaves over the chased background (Fig. 5, 2 ). In our opinion, the images on both vessels are

Fig. 5. Heptagonal cups from Inner Mongolia.

1 – cup from the tomb of a Khitan official (Du Hanchao, 2014: Photo on p. 176); 2 – silver gilded cup (Treasures on Grassland, 2000: Tab. 339). The scale is not specified.

Fig. 6. A modern copy of a gilded octagonal cup from a private collection (photograph by S.G. Narylkov) ( 1 ), graphical reconstruction of a silver octagonal cup with a handle in the form of a griffin (photo by the author) ( 2 ). The scale is not specified.

associated with the plot of the popular Chinese story about “seven wise men in a bamboo grove”.

Notably, all polygonal cups are made at a high professional level and are highly artistic products. The creative impulse inherent in the products of Tang artisans was perceived by modern Chinese craftsmen: they manufacture high-quality full-fledged copies and replicas. Cups made of metal (Fig. 6, 1 ) and porcelain can be found on sale.

Archaeologically intact sexagonal cups (type 1 – with a handle in the form of a horse-shaped griffin’s head) have not survived to this day. Available solitary fragments make it possible to reconstruct the shape of a vessel. For instance, the burial with a horse in the kurgan of Nainte-Sume, in the Tola River basin in Mongolia, yielded a destroyed hexagonal rim of a vessel, and an accompanying cast handle in the shape of a griffin’s head (Borovka, 1927). There is every reason to believe that these are parts of one cup. Two more similar handles were found in the south of Siberia. One of them was discovered in 1989 during excavations of a burial with a horse in kurgan 34 at the Markelov Mys II cemetery, in the Novoselovsky District of the Krasnoyarsk Territory (Mitko, 1999). The other handle was found outside of an archaeological context near the village of Chernoye Ozero, in the Shirinsky District of the Republic of Khakassia, in 2012 (Oborin, 2019: Fig. 17). Comparative analysis allows us to draw a conclusion about the typological identity of the three handles and to make a graphical reconstruction of the cup (Fig. 6, 2 ).

Conclusions

Ancient artistic products made of precious metals had little chance of surviving to this day and getting into museum collections. At all times, gold and silver things became the desired prey for “treasure hunters”. Very often they were broken, crushed, and valued by the weight of the precious metal.

There is no doubt that, having seen a bronze vessel with a representation of a hunting scene and a cup from the vestry of Fort Karaulny church, such an insightful and versatile scientist as D.G. Messerschmidt could not help but appreciate its artistic and historical value. The researcher managed to purchase the cup and deliver it to St. Petersburg; it was included in the collection of “oriental silver” of the Hermitage, but it has not survived to this day.

Assessing the significance of imported metal tableware in the context of the development of the Yenisey Kyrgyz culture, it should be noted that it evidences the inclusion of the Altai-Sayan population as a full partner into the system of trade and economic relations between the central and eastern parts of Eurasia. The appearance of octagonal cups in the Middle Yenisey falls in the 8th–9th centuries, the time of the Kyrgyz-Uyghur confrontation and the political and economic rise of the Kyrgyz Khaganate. We should agree with Marshak that the morphological and stylistic features of the cup from the vestry of Karaulny Fort church suggest affiliation of its origin to the craft school of Sogdian toreutics.

In archaeology, imported items are considered trade markers. According to written records, the Kyrgyz maintained constant contacts with the Arabs (dashi), Tibetans (tufan), and Karluks (galolu), and periodic contacts with the Chinese. From the country of Dashi, a caravan of 20 (sometimes 24) camels, loaded with silk fabrics, arrived to them every three years. Judging by the archaeological finds, the imported Western goods included glass and stone beads and, probably, metal tableware. In return, musk, furs, birch wood, and Hutu horn (tusks of walruses and narwhals) were exported (Bichurin, 1950: 55; Bartold, 1963: 490, 493). The question of the origin of sexagonal cups with handles in the form of a horse-shaped griffin’s head is debatable (Fig. 6, 2). In our opinion, these could also have been made by Sogdian artisans.

The bronze vessel bearing a hunting scene and the octagonal cup with an Uyghur inscription from the Nad Polyanoi cemetery are of Chinese origin. The iconography includes complex syncretic animal and plant symbolism created by Tang artists. Jewelers produced realistic images on small-sized facets. As for the silver cup from the vestry of Fort Karaulny church, its shape was popular not only in the western regions of Asia, but also in China, thanks to Sogdian merchants.

Gavrilova, who excavated the Nad Polyanoi medieval cemetery, did not consider the similarity of the images on the cup’s facets to Chinese images as evidence that the vessel was made in China, and suggested “to look for the master” in the Turfan oasis (1968: 28). In our opinion, this cup could have been delivered to the Turfan principality by the trade route from one of the main centers of mass production of luxury goods. During the reign of the Tang Dynasty, these were capital cities, each with a population of million: Chang’an in the western part of the empire, Luoyang in the eastern part of the empire. The demand for luxury goods stimulated here the development of jewelry production and the concentration of a huge number of merchants and travelers from many parts of Asia, students and monks, poets and artists, representing various aesthetic trends and forming a creative atmosphere. These included the culture of drinking alcoholic beverages, which was, judging by the poetic works, as high culture as the tea ceremony.

In Turfan, in accordance with the tradition prevailing in the Turkic environment, the cup from Nad Polyanoi was provided with an engraved inscription, and during the long existence of the Kyrgyz-Uyghur frontier, it ended up in the Middle Yenisey.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 20-18-00111).

The author expresses his gratitude to S.A. Komissarov and M.A. Kudinova for consultations and translation of Chinese papers.

Список литературы “D.G. Messerschmidt’s cups”

- Bartold V.V. 1963 Kirgizy. Istoricheskiy ocherk. In Sochineniya, vol. II (1). Moscow: Nauka, Gl. red. vost. lit., pp. 471-543.

- Bichurin N.Y. (Hyacinth). 1950 Sobraniye svedeniy o narodakh, obitavshikh v Sredney Azii v drevniye vremena, vol. I. Moscow, Leningrad: Izd. AN SSSR.

- Borovka G.I. 1927 Arkheologicheskoye obsledovaniye srednego techeniya r. Toly. In Predvaritelniye otchety lingvisticheskoy i arkheologicheskoy ekspeditsii o rabotakh, proizvedennykh v 1925 godu, vol. 2. Leningrad: Izd. AN SSSR, pp. 43-88.

- Du Hanchao. 2014 Semigranniy pozolochenniy serebryaniy kubok. In Xianging chenghui: Caoyuan sichouzhi lu venu jinghua. Tala zhu bian (Shining Bright for Each Other: the Elite Cultural Values of the Steppe Silk Road). Hohhot: Nei menggu renmin chubanshe, pp. 175-177. (In Chinese).

- Evtyukhova L.A. 1948 Arkheologicheskiye pamyatniki Yeniseyskikh kyrgyzov (khakasov). Abakan: [Tip. izd. “Sov. Khakasiya”].

- Gavrilova A.A. 1968 Noviye nakhodki serebryanykh izdeliy perioda gospodstva kyrgyzov. KSIA, iss. 114: 24-30.

- Gyllensvärd Bo. 1953 Chinese Gold and Silver in the Carl Kempe Collection. Stockholm: Nordisk Rotogravy.

- Gyllensvärd Bo. 1957 Tʼang Gold and Silver. Stockholm: The Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. (Bulletin of the Museum of for Eastern Antiquities; No. 29).

- Hansen V. 2003 The Hejia village hoard: A snapshot of China’s Silk Road trade. Orientations, vol. 34 (2): 32-43. (In English and Chinese).

- Kieser A.A. 2015 “Golden age” just for the living? Silver vessels in Tang dynasty tombs. Tang Studies, vol. 33: 62-90.

- Kopaneva N.P. 2006 “Vozvrashcheniye” arkheologicheskoy kollektsii Messerschmidta. Nauka iz pervykh ruk, No. 5 (11): 72-79.

- Korol G.G. 2008 Iskusstvo srednevekovykh kochevnikov Yevrazii: Ocherki. Moscow, Kemerovo: Kuzbassvuzizdat.

- Li Laiyu. 2014 Gilt eight-edged silver cup with music pattern. In China Archeology. Archaeological Encyclopedia. http://www.kaogu. cn/cn/kaoguyuandi/kaogubaike/2014/0715/46832.html

- Louis F. 2011 Metal objects on the Belitung shipwreck. In Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds. Washington: Smithsonian Books, pp. 84-91.

- Marshak B.I. 1971 Sogdiyskoye serebro: Ocherki po vostochnoy torevtike. Moscow: Nauka.

- Messerschmidt D.G. 1962 Forschungsreise durch Sibirien. 1720-1727. Vol. 1: Tagebuchaufzeichnungen, 1721-1733. Berlin: Akademie-Verl.

- Messerschmidt D.G. 2012 Dnevnik. Tomsk-Abakan-Krasnoyarsk. 1721-1722. Abakan: Zhurnalist.

- Michael C. 1991 Teller IV, Royal Chinese Treasures: Tang and Song Dynasties. Williamsburg, Virginia: TK Asian Antiquities.

- Mitko O.A. 1999 Obraz grifona v iskusstve narodov Yevrazii v drevnetyurkskuyu epokhu. In Yevrazia: Kulturnoye naslediye drevnikh tsivilizatsiy, iss. 2. Novosibirsk: Izd. tsentr Novosib. Gos. Univ., pp. 7-10.

- Oborin Y.V. 2019 Serebryanaya posuda. Noviye nakhodki iz Yuzhnoy Sibiri. URL: https://www.academia.edu/40084355

- Qi Dongfang. 1998 Izucheniye zolotykh i serebryanykh sosudov sogdiyskogo tipa tanskogo perioda (k diskussii o sosudakh s ruchkami) (A Study of the Sogdian Type of Gold- and Silver-Wares of the Tang Period (with the Handled Cup as the Center of Discussion)). Kaogu xuebao, No. 2: 153-169. (In Chinese).

- Radlov V.V. 1891 Sibirskiye drevnosti, vol. 1 (2). St. Petersburg: Izd. Imp. Arkheol. komissii.

- Shcherbak A.M. 1968 Drevneuygurskaya nadpis na serebryanoy charke iz mogilnika Nad Polyanoy. KSIA, iss. 114: 31-33.

- Smirnov Y.I. 1909 Vostochnoye serebro. Atlas drevney serebryanoy i zolotoy posudy vostochnogo proiskhozhdeniya, naidennoy preimushchestvenno v predelakh Rossiyskoy Imperii, Y.I. Smirnov (pref.). St. Petersburg: Izd. Imp. Arkheol. komissii.

- Szmoniewski B.S. 2016 Metalwork in gold and silver during Tang and Liao times (618-1125). In Between Byzantium and the Steppe Archaeological and Historical Studies in Honour of Csanád Bálint on the Occasion of His 70th Birthday. Budapest: Inst. of Archaeol. Research, Centre for the Humanities, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, pp. 231-248.

- Treasures on Grassland. 2000 Archaeological Finds from the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. By Shanghai Museum of Art. Shanghai. (In English and Chinese).

- Tunkina I.V., Savinov D.G. 2017 Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt: U istokov sibirskoy arkheologii. St. Petersburg: ElekSis. Vasmer M. 1987 Etimologicheskiy slovar russkogo yazyka: In 4 vols. Vol. 4: T - yaschur. [2nd edition]. Moscow: Progress.

- Worrall S. 2009 Made in China. A 1,200-year-old Shipwreck Opens a Window on Ancient Global Trade. URL: https://www. nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/tang-shipwreck (In English).